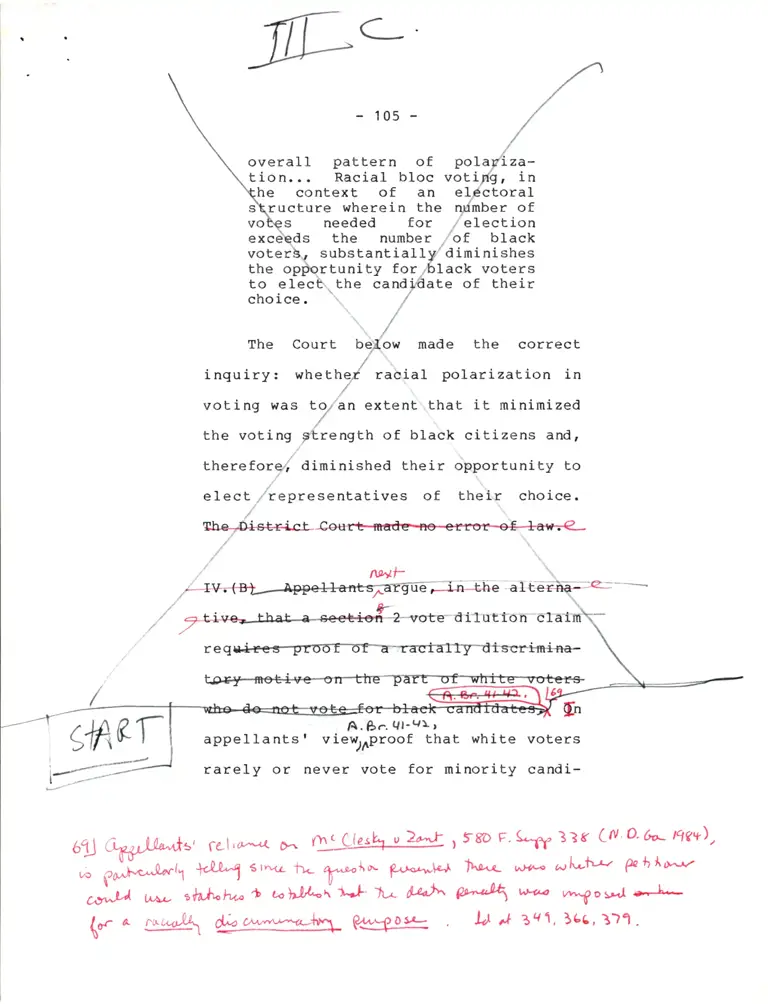

Annotated Partial Draft of Brief Section III-C

Working File

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Annotated Partial Draft of Brief Section III-C, 1985. fbd1cc7d-db92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/305fdb82-b2b5-4780-b2ea-38634564df54/annotated-partial-draft-of-brief-section-iii-c. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

g+fi,eT

61) *#y,t s, ftl,a^.,t h rylL:s\ " >-+.

105

overall pattern of polay'Lza-

Eion... Racial bloc votiflg, in

,^ff 3 3 s' Co o. C,* ng'?) ,

t/,t41q 6)Lt ^, pe h l6^t'

t^Hta v+rf o Sil 5..J*

3r/1, 366, 3)l .

the context of an elctoral

s\ucture wherein the ryimber of

for ,/ election

the number ,/of black

'diminishesvoterb, substantialllr' diminishes

the opdortunitv for,6lack voters

choice. t'to elecb. the candidate of theircll

i//

The Court below made the correct

inquiry: whethe/ raeial polarization in

voting was Lo7'an extent that it minimized

//the voting ptrength of black citizens and,

thereforqi diminished their opportunity t.o

elec L ,/'representatives of thelr choice.

Eb€+ti#E+;LcL

/\

k\'

," -2-votre dlf'ut'ton"-eIa-1Tl

requ iscriti+*

t-gElr motive orr Ehe pAft of ''t obers

A. Br^. 9t'e\ t

appellants I viewrnproof that white voters

rarely or never vote for minority candi-

) 58D F.

ho"l-

et*u!\

tl.,l

106

dates does not establish the presence of

pol ar i zed

plaintiff

n

voti ng.*';{ther, they urse, a

must adduce probative eviden""F fiLove )''' n""l/ (**

of the motives of the individual white

69

6.eg.ti.".

:oChar wutT*"1'*-l\

70 Appellants argue in particular that proof

of motives of the electorate must take the

form of a multivariate analysis. (App.Br.

43-44). No such multivariate analysis was

presented in White v. Regester or any of

the other dilffih Congress

referred in adopting section 2. Although

appellants now urge that evidence of a

multivariate analysis is essential as a

matter of law, no such contention was ever

made to or considered by the district

court.

Solicitor suggests that etretr

r{ou est.ablish a "prima f acie ca

polari

could

"which

voting, but that such e

"rebuttedn by a defe e study

ther factors in account. "

(U.S.Br. II, n.57 ) Appe ants in the

instant case d adduce a

such analysis. (Tr) r

does not indicate t-"other factors

should be considered/i such a studyr oE

explain what they'ltima factual issue

would have to be,fesolved i ight of such

a rebuttal. is argument represent

an ef forE/y the Department Just ice

which u,,in6uccessfully sought tci

CongregC to place an intent require

2, lo persuade this Court to d

107

voters at issue, and must establish that

they cast their ballots with a conscious

intention to discriminate against minority

candidates because of the race of those

70'

candidates .'- fApryr.Br. 42-44tr

This proposed definition of polarized

voting would incorporate into a dilution

claim precisely the sort of intent

requirement which Congress overwhelmingly

voted to remove

Congress was

clarifying the

from section 2. Although

prirnarily concerned to

statutory standard after

Mobile v. Bolden, Con-

gress' reasons for objecting to the intent

requirement in Bolden are equally applic-

able to the intent requirement now

proposed by appellants.

108

Congress opposed any intent require-

ment, first, because it believed that the

very litigation

i nev i tably

ties:

lTlhe Committee has heard

persuasive testimony that the

intent test is unnecessarily

divisive because it, involves

charges of racism on the partl

of individuals or

communities. . .

entire

Litigators representing excluded

minorities will have to explore

the notivations of individual

council members, mayors, and

other citizens. Such inquiries

can only be divisive, threaten-

ing to destroy any existing

racial progress. It is the

intent test, not the results

test that would make it neces-

sary to brand individuals as

racist in order to obtain

judicial relief .

fis.Rep

. 36lD 71

.6

See also Additional Views of Sen. Dole,

193 (the intent test "also causes divi-

siveness because it inevitably involves

charges that the decisions of officials

were racially motivated. ")

of such issues would

stir up racial animosi-

71

109

Congress contemplated that under the

section 2 results test the courts would

not be requiredr €rs appellants suggest, to

"brand individuals as racist." €iLcltrttr&-

.ho-

the divisive effect of

+

7o@ would be infinitely

greater if a plaintiff were required to

prove and a federal court rrere to hold

that the entire white citizenry #

- b.qoY't

had acted with racial ms'ti-rrcs.

Second, Congress rejected the intent

test because it created 'an inordinately

difficult burden for plaintiffs in most

cases.' (S.Rep. 36) The Senate Committee

noted the general difficulty of proving

the existence of a discriminatory intent,

and expressed particular doubts about

whether it might be legally impossible to

inquire into the motives of individual

voters:

7

1

110

[T] he courts may rule that

plaintiffs face barriers of

"legislative immunityr" both as

to the motives involved in the

legislative process, and as to

the motives of the majority

electorate when an election law

has been adopted or maintained

as a result of a referendum.

( Id. ) ( footnotes omitted ) 72

The Senate Committee expressly referred to

a the n recent Fif t.h Circuit decision

holding that the First Anendment forbade

any judicial inquiry into why a specific

voter had voted in a particular *ay.73

Congress thought it unreasonable to

require plaintiffs to establish the

motives of local officials

i a#reqttent-I y -kept--records. -of .. th-e i r a ct.i-ons"---9-

2=a+d-aurposes; establishing the motives of

72 See also Additional Views of Sen. DoIe, p.

193 (intent test "places an inordinate

burden of proof on plaintiffs. . . o

)

73 rd. n.'135, citing Kirksey v. City of

G-ckson, 699 F.2d ffi

cTE?iffi-nq Kirksey v. City of Jackson, 663

F':ZaC9=

of whom keep any records of le,,*-ez/why

they voted, and all of whom are constitu-

tionally immune from any inquiry into

their actions or motivations in casting

t,heir ballotsr74

infinitely more difficult task.75

111

thousands of white voters, none

would clearly be an

74 See also Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399,

T0-(196mi11s, 664 F.zd

600, 608-9 (5tmth Alameda

Spanish Speaking org. v.CTEy oEffiT'

c

ffiiEed States v. nxffitive Committee of

Denpcratic Paarty of Greene County, AIa.7

).

The courts have consistently entered

findings of racially polarized voting

without imposing the additional burdens

ncw urged by appellants. See I'tississippi

Republ i can Ex e c u t ive comm iE e-Tln-f5o-Fil

fE-ummary aEffrmance of district court

using correlation test). See also Rogers

v. Lodge, supra, 458 U.S.€t--6Z3TEcIiTF

@F.2d at 1043 n.12; MEienE-o

ffinffisupra, 731 r.2d at 1567-i:,34;

75

ffi. GeAfrlEn county schoor Board , 69l

rT-T96'2l iTilIins v.

Helena, 67 5 F . 2tr2TT]nT

[r?-ff d mem. 4 59 U. S. 80 1

( 1982 ) ; city of-T6?E TFthur v. United

States,

ID:m 1981), aff 'd as9 u.s. 1s9 (1982);

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325, 337

ffi; City of Rome v. United

States , 472 F. S

191-9]1 3rrf 'd 446 U.S. 156 (1980); city qf

eeterski@f . united states | 354 F;S[pp.

Z)r aff'd 410

u.s. 962 (1973).

76@ Appellants'expert .t ,.testifi?-il EEaf no^1d1 l<tt^,oub

wL.,l-ht Co*5,d,trs r^prl*@, SUCh aS a Candidaters

skiIls or positi'ons on the issuesT *R4- a,rrc nol 6o*^lr'l,nhl<.

112

Counsel for appellants contend that

the plai ntiffs in a section 2 action

should be required to establish the

motives of white voters by means of

statistics, but at trial appellants'

statistician conceded it would be impos-

sible to do

"o.75

thaE a quanEi Eat{ ve stati st i cal apprea"en-r-

fuegression ana'lysis, was

. *pt>e1:larrts

€rt* refl=es,s-i@i-ng McCleskey v.

zant, 580 F.Supp. 338 (N.D;6il-13Tlff ,

| // t 4

, tnt ,nr|t ' - n ;l6i-' 1,.-!> f 2),4

' I'-" i

aTFTa, F.2d ( 5th Cir. 1 985 ) ,

EpeTtffig, No.TF @ ---((<ot(55rt'>',

7' are incapable'of demonstrating racial

( intent wherer ds here, "qualitative"

I -^ :r:-L1^ ri cc- -- i -- -^1--- ti rprquantifiable dif ferences are involved.

j 580 F. Supp. at 372.

I

h

T

ile A"A r.,o)' sr.r11r:| h+J 6uA *n nffil4r,, a"JJ L pt4l,t ,^J/

[! .nnu4-el V 4-,d ^o\**L) ]'r. 6rrrF.r**ra^-.'tr. Wbct^,-l o'* -

llgg t lqTo , l'tt(, t'lCO .

113

Third, Congress regarded the presence

or absence of a discrininatory motive as

largely irrelevant to the problem with

which section 2 was concerned:

[T]he intent test ... asks the

rdrong question.... tIl f an

electoral system operates today

to exclude blacks or hispanics

from a fair chance to partici-

pate, then the matter of what

motives were in an officialrs

mind is of the most limited

relevance. (S.Rep. 36)

The motives of white voters are

equally beside the point. The central

issue in a dilution case is whether, not

why, minority voters lack an equal

opportunity to elect candidates of their

choice. If an at-large system in fact

creates Uuift/n headwinds that put

I

rninorities at a disadvantage, section 2 is

violated regardless of the precise

mechanisn which creates that disadvantage.

114

I

On appellant's view, polarized voting.7

occurs only when whites vote against black

candidates because of their race, but not

when whites consistently vote against

black candidates because of their posi-

tions on issues about which the black and

white communities happen to disagree.

s

f{-ecfion

z guarantees

to minority voters an equal opportunity to

elect officials "of their choicer" not 'of

their race. " BIacks may welI choose

particular candidates because of their

positions favoring affirmative action or

economic sanctions against South Africa;

prilh ,"dr 7)f

n#

gcr$--Ta {e --oo. P1toL@ *-,A-14- drt'*d4*t?

-{> e*t+ illtoe-,t -t Le

\3,-Ur1**

4-fuL a fuv.-I;t-rnfar& a,r,tl+t.,S r.n-Ll ff'or.f. ]\.--

<ttrt;l*| b"ltu-'

'iA;A i -=,

a