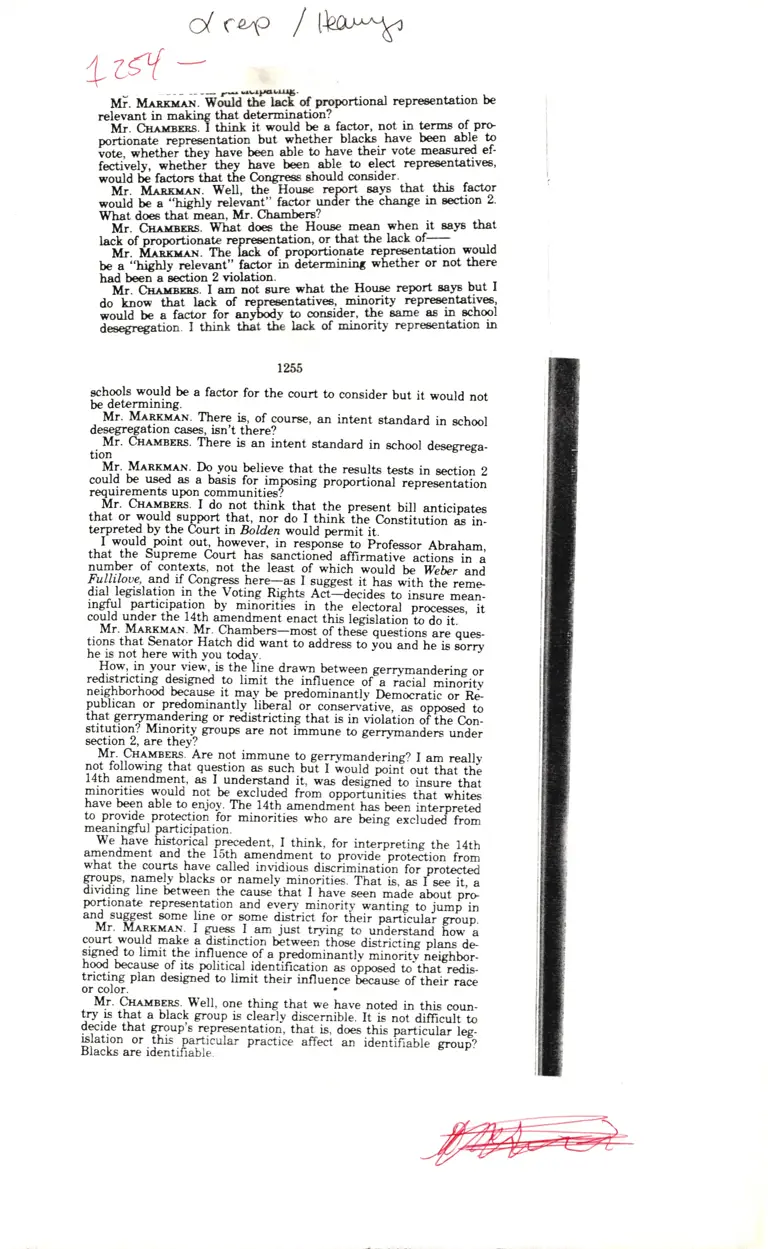

Attorney Notes Pages 1254-1255

Annotated Secondary Research

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Attorney Notes Pages 1254-1255, 1982. efaf67d2-e092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/30e1a4bd-222f-4807-a722-99339ffdbdf9/attorney-notes-pages-1254-1255. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

d cw /tka/'^1f

rrd. rueriln. w"fiaffrlfi of proportional repreaentation be

r.elevant is mnking that determination?--n{r. Ctrnrns. f *li',t it would be a fac'tor, not in terms gf-pto

oortionate representation but whether blacks have been able to

;il;-*h;th;ithey have been able to have their vote measured ef'

iecti"etv. whethei thev have been able to elect nepresentatives,

would 6i factors tbat tLe Coneress ehould conaider.'

Mr. Urnsrl\l. \f,ell, the-House rePort eays t'hat this factor

*o-uti b" " "highty relevant" lastor under tr5g chnnge in eection 2.

What does thafmean, Mr. Chambers?'

Mr. -Cn .uEB& iryfat doea the House mean when -it says ]ha;

hck of Jrooortionate reprtaentation, or that the lack of-

-tvtt.-fi]f*n* fte lack of propbrtionate repreaentation would

be-;;bgh1y rcIeranC' factor iri dtiterminiry whether or not t'here

had ben a irection 2 violation.

M".-C!^EEBs. I am not sure what the House rePort aaSn but I

dt k,j;th8a lack of repreaentatives, rninslity repreeentatires,

;;"td b" a factot for any$ody to consider, the aa'me as in echool

e'oego$tioo. 1 +.hink tlit Ui.e 1ack of rninolrity repreaentation in

r255

echools would be a factor for the oourt to coneider but it would not

be determining.

Mr. Menrrr^x. msrq is-, of counse, an intent standard in school

desegregation csses, isn't there?

Mr. cgerrsrns. There ie an intent standard in school desegrega-

tion

Mr. Mrnxuex. Q yg, believe that the reeults tests in eection 2

could be used as a basis for imposing p"opoJionJ *pril"tation

requirements upon communities! -

Mr. cne.runsns. I do lrot think that the preserrt bill anticipates

that or yguld. support !hq!, _n_or do I thinkite constiiuEon ris in-

terpreted.by the C,ourt in hldcn would permii it.

-----------

- I would^noint out, however, in respo'nse to Frofessor Abraham,that.the supreme crcurt has sanctio'nea arri"mliire actions in anumber of contexts, not the least of which *ouid b"-ii;b", ure

{\rlh.-lou9,-and if c,ongress lrere;qs I suggest it tias wiirr'ii"

""or*$at^ t-egislation in the voting Rights Acr"-decidJto il";; mean-ingful participatior: bv mForitles in the electoral proceeses, it

could under the 14th nmsldmslt enac,t this legisiaaio" i; d; it. ' -

Mr. M.r,nruen. Mr. ch"mbers-moot of thes-quotio.rrii" q"*

tions that Senator Hatch did want to address t i;r-;et;GJo",i,he is not here with vou todav.

How, in your viei,_is the iine drawn between-gerrymandering or

I*f,tl_"_tjlq,dgisnd to limit the influence of-a 6;.1-;i";'"ilt

neighborhood because it pay-be predominantly Democratic or Rip.ublican or predominantly iiberil or conservati"elas opiiou.a t"that gerrym-andering or r&istricting that is in Gotaiio" of,[rr" c""-stitution? Mingrity^ g.o,rpu are not Inmune to gerrymandlrs unde.

section 2. are thev?

Mr. cnerrs"*s. Are not immune to gerrymandering? I am reallv

not, following that question as such urit I ivouta-p.i"T ,irt tir;;i;l4th amenrtrnent, as I. understand it, was desided to insure thatminorities would not be excluded frbm opportirnitiC that whiG

have been able to enjoy. the. I4th ""'endmL'na has;-bi; ;t""d;t"dto provids-protectjon -for

minorities who

"re

Uei"g-";"til;d'?;;;

meaningful participation.

rve trave historial

-precedent, r think, for interpreting the 14thamendment and the Isth a'nendment to providi'pioG&ion rro-what the courls hav_e called invidious dir"ffii";tifi -f* ;;;t€cted

fl_o_qry,_rr,?-ely blacks.or namely-min_orities. fnat G, ; fr* it ;

<u,.,dmg rme between the cause that I have seen made about pio

ry*i:.ff _^re_presentation and every

.

minority wan-iing t"-:u-p i"

an-d_ suggest some rine or some .ristrict for their particulai group.Mr. Menxurx. I gu"q" I nm just t.yirrg t"-";d;;i;; f,il;court would make a ilistinction between th"ose disiricii"e pla"s a*grgn* 1p limit the infl.uencg.o.f a predominanttv -i"oriii i"ishs;-

|q4. b"e* of its political identification as oirposea' to"thai reais-tncting plan designed to t;'.'i1 their influence b6cause of th;ir r;;or color. .

Mr. cnerrssRs. well, one thing that we have noted in this coun-q.v.T th"t a black group is creairy discernible. li is "JairrcultG9_fr.9:_rh9t F]rgup's representation, that is, does this particular lqg-rslatron or this oarticular practice affect an identifiable grou;?

Blacks are identifiable.