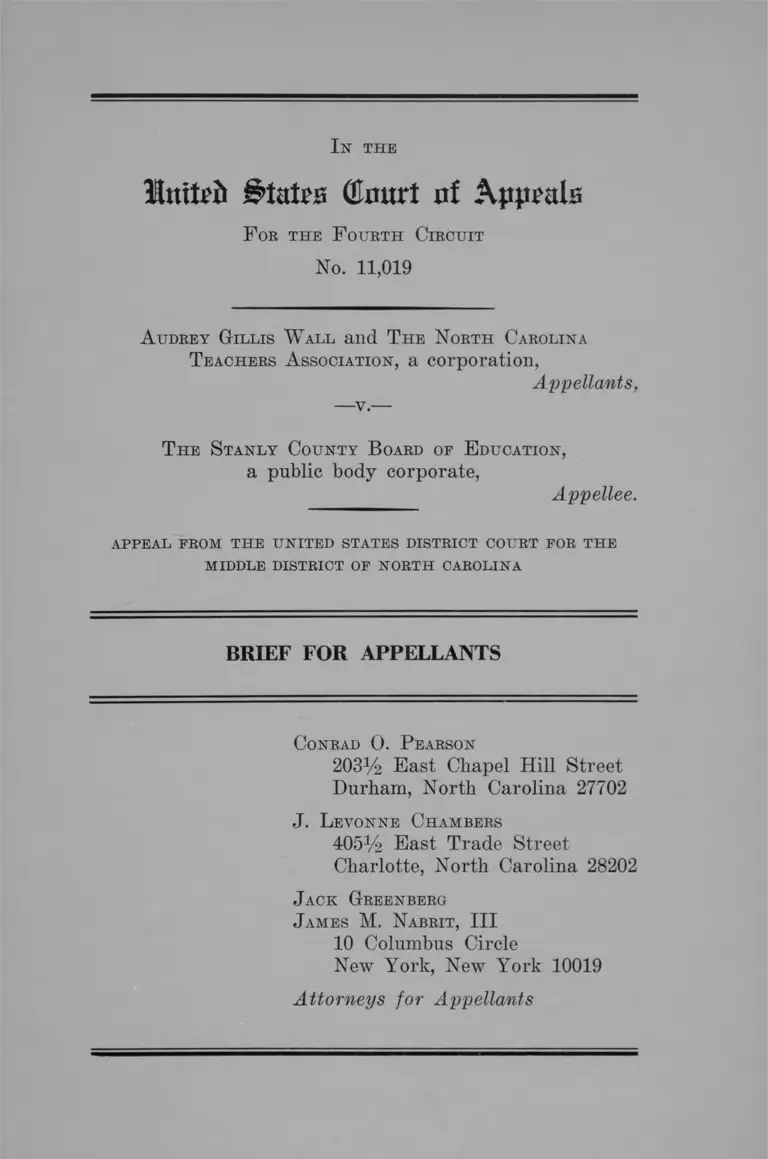

Wall v. Stanley County, North Carolina Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wall v. Stanley County, North Carolina Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1966. d1a5e259-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/32af8765-4548-4fab-8521-08b5f50e6c29/wall-v-stanley-county-north-carolina-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Httitei States (Enurt of Appeals

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 11,019

I n THE

A udrey G illis W all and T he N orth Carolina

T eachers A ssociation, a corp ora tion ,

Appellants,

— v .—

T he S tan ly C ounty B oard of E ducation ,

a public b o d y corp orate ,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM TH E U NITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF N O RTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

C onrad 0 . P earson

2033/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

J. L evonne Chambers

4053/2 East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ..................................................... 1

Statement of Facts ........................................................... 5

Questions Involved............................................................. 8

A rgum ent

Preliminary Statement ..................................................... 9

I. The School Board’s Dismissal of Plaintiff Wall

and Others of Her Class, in Attempting to De

segregate Its System, With No Consideration

or Comparison of Their Qualifications With

Other Teachers in the System, While Hiring-

New White Teachers to Fill Positions in White

Schools Constituted a Clear Denial of Due Proc

ess and Equal Protection of Law, Entitling

Them to Reinstatement and Damages ............... 12

II. Plaintiffs Are Entitled to An Order Enjoining

Further Racial Employment, Assignment and

Dismissal of Teachers and School Personnel .... 17

C onclusion ..................................................................................... 19

T able of Cases

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 382 U.S.

103, reversing 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965) .............. 12

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 345 F.2d

310 (4th Cir. 1965) ......................................................... 18

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 317 F.2d

429 (4th Cir. 1963) .....................................................14,18

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington County,

324 F.2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) ...................

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

18

5

11

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966) .......................... 9,11,12,13,

14,16,17,18

Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford County,

231 F. Supp. 331 (D. Md. 1964) ................................11,16

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278 .... 13

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, 360

F.2d 325 (4th Cir. 1966), reversing 242 F. Supp. 371

(W.D. Va. 1965) .................................................... 9,11,12,

13,14,15,16

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F.2d

118 (4th Cir. 1962) ......................................................... 14

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 .................................... 16

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir. 1966) .......13,14,

15,16

PAGE

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County, 249

F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va. 1966) .................................. 12,17

Olson v. Board of Education of Union Free School

District No. 12, 250 F. Supp. 1000 (E.D. N.Y. 1966).. 18

Rackley v. School District Number 5, Orangeburg

County, ------ F. ------ (Civil No. 8458, D. S.C.

1966) .............................................................................. 13,16

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232 .....13,14

Service v. Dulles, 354 U.S. 365 ........................................ 16

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ............................ 12,17

Slochower v. Board of Education, 350 U.S. 51 ............. 13

Ill

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School Dis

PAGE

trict No. 32, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir. 1966) ...........11,12,14

Smith v. Hampton Training School for Nurses, 360

F.2d 577 (4th Cir. 1966) ............................................. 16

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 .................................... 13

Vitarelli v. Seaton, 359 U.S. 353 ...................................... 16

Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington County,

357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) ....................................... 18

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 363 F.2d

738 (4th Cir. 1966) ................................................ 12,17,18

Wickersham v. United States, 201 U.S. 392 .................. 16

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 .............................. 13

Statute :

N.C. Gen. Stat. §§ 115-58, 115-72 ...................................... 17

Other Authorities:

N.E.A. Convention, Speech by the President, July 2,

1965, New Y ork ............................................................... 9

National Education Association, Washington, D. C.,

“Report of Task Force Appointed to Study the

Problem of Displaced School Personnel Related to

School Desegregation and the Employment Studies

of Recently Prepared Negro College Graduates Cer

tified to Teach in 17 States,” December 1965 .........10,11

Ozman, “ The Plight of the Negro Teacher,” The Amer

ican School Board Journal, September 1965 ........... 10

U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare,

Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegrega

tion Plans under Title VI of Civil Rights Act of

1964 ...................................................................... 9,12,14,17

I n the

luttrii States (Court of Apprala

F or the F ourth C ircuit

No. 11,019

A udrey G illis W all and T he N orth Carolina

T eachers A ssociation, a corp oration ,

Appellants,

—v.—

T he S tan ly C ounty B oard of E ducation ,

a public body corporate,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM TH E U NITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF N O RTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This appeal is from a final judgment (94a) (------ F.

Supp. ------ ) of the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina, Salisbury Division, dis

missing plaintiffs’ complaint and denying injunctive relief

to plaintiffs and members of their class who were dismissed

or denied reemployment as teachers for the 1965-66 and

subsequent school years following the transfer of Negro

pupils from all-Negro schools to formerly all-white schools

in the Stanly County School System.

This action, seeking a preliminary and permanent injunc

tion against the racially discriminatory policies and prac

tices of the Stanly County Board of Education in hiring,

2

assigning and dismissing teachers and professional school

personnel, was filed on August 11, 1965, by a Negro school

teacher and the North Carolina Teachers Association, a

professional organization, consisting principally of Negro

teachers and professional school personnel. The plaintiffs

alleged (la-6a) that the School Board had in the past and

was presently hiring, assigning and dismissing teachers and

school personnel solely on the basis of race and color, with

Negro teachers assigned solely to Negro schools, and white

teachers assigned to white schools; that pursuant to the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, the defendant adopted a plan,

effective with the beginning of the 1965-66 school year, for

the assignment of pupils which permitted students to indi

cate the school they desired to attend; that pursuant to this

plan, approximately 100 Negro pupils requested reassign

ment from all-Negro to previously all-white schools; that

pursuant to the School Board’s policy of making racial

assignments of teachers and school personnel, the School

Board dismissed the individual plaintiff and others of her

class, solely on the basis of their race and color, in an

ticipation of the decrease in enrollment at the Negro

schools; that the School Board hired new white teachers

and school personnel to fill positions in the formerly all-

white schools and refused to consider the individual plain

tiff and others of her class solely because of their race

and color. The plaintiffs prayed that the Court enjoin the

School Board and those acting in concert with it from

employing, assigning and dismissing teachers and other

professional personnel on the basis of race and color (6a)

and for reinstatement of the individual plaintiff in the

same or comparable position (40a-41a).

The School Board filed an answer on or about Septem

ber 3, 1965, denying the material allegations of the com

plaint and moving the Court to dismiss and for summary

B

judgment (8a-30a). Plaintiffs’ response to the motion to

dismiss and for summary judgment was filed on October

15, 1965 (31a-34a). The motions of plaintiffs for pre

liminary injunction and of defendant to dismiss and for

summary judgment were heard on October 20, 1965 and

denied without prejudice on November 9, 1965 (39a).

Initial and final pretrial conferences were held on October

20, 1965 (35a) and February 2, 1966 (42a-50a), respec

tively.

The cause came on for hearing on April 27, 1966 at which

time plaintiffs intrduced several exhibits, consisting of

answers to interrogatories, depositions of Luther Adams,

Robert McLendon, G. L. Hines, Reece B. McSwain, and

Audrey Gillis Wall; teacher allotments, directory, minutes

of Board meetings, proposed policy changes of the defen

dant Board; letters of Luther Adams and Robert Mc

Lendon; form contract for instructional services; and the

oral testimony of Luther Adams and plaintiff Wall. The

case was continued until the following day at which time

plaintiffs introduced the oral testimony of E. Edmund

Reutter. The defendant offered no evidence.

On September 15, 1966, the District Court filed its Find

ings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Opinion, finding that

Negro teachers and principals through the 1964-65 school

year had been assigned to Negro schools and white teachers

and principals to white schools (56a); that there was no

change in the racial composition of teachers and staff for

the 1965-66 school year with the exception of one Negro

teacher hired at a predominantly white school in January

1966 (62a); that pursuant to the freedom of choice plan

instituted by the defendant for the 1965-66 school year ap

proximately 300 Negro pupils transferred to formerly all-

white schools resulting in a reduction in allotment of

teachers at Negro schools and an increased allotment of

4

teachers at white schools (58a, 60a); that the Board

adopted no specific provisions to govern assignment of

teachers for the 1965-66 school year who might he affected

by the shifting of pupil enrollment and did not advise the

principals that teachers of a different race might be em

ployed at their respective schools (60a); that although

plaintiff Wall had initially been recommended and ap

proved for employment for the 1965-66 school year she

was denied employment following the reduction in allot

ment of teachers at her school because of her temperament

and attitude (64a-65a); that no objective comparison was

made of her qualifications or the severity of her alleged

faults with those of other teachers in the system; that the

practice and procedure followed by the defendant fell short

of the generally accepted practice (61a-62a, 66a).

On the basis of these findings the Court concluded that

neither the individual plaintiff nor members of the class

were denied due process of law although deefndant’s prac

tice varied from the generally accepted norm (76a, 78a);

that plaintiff Wall was not denied equal protection of the

laws although there was no objective comparison between

the plaintiff and other teachers in the school system (84a)

and although it was clear that the plaintiff would have

been employed had there been no reduction in teacher allot

ment at the Negro school (82a); and that plaintiffs were

not entitled to general injunctive relief reasoning that the

plan adopted by the defendant on April 15,1966 (216a-232a)

was not constitutionally objectionable. The Court thus

denied all relief and dismissed the complaint (94a).

From this judgment, the plaintiffs, on September 26,

1966, filed this appeal (517a).

5

Statement of Facts

Despite the ruling of the Supreme Court in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. in 1954, the seventeen schools

in the Stanly County School System (101a) were op

erated on a completely segregated basis until two Negro

pupils requested reassignment for the 1964-65 school year

to the all-white North Stanly High School (293a, 351a, 55a-

56a). Negro students and teachers were assigned to three

all-Negro Schools—South Oakboro, Lakeview and West

Badin (101a, 294a, 351a). White students and teachers

were assigned to the remaining fourteen all-white schools.

Negro students completing elementary school at South Oak

boro and Lakeview were, and still are except upon request

for reassignment to another school (301a-302a), trans

ferred to the all-Negro Kingville High School in another

school district, a practice long condemned by the Supreme

Court and by this Court.

For the 1965-66 school year, the defendant, pursuant to

the requirements of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, adopted

a plan for the assignment of pupils which permitted them

to indicate the school they desired to attend (299a, 352a,

19a-30a). Pursuant to this plan approximately 300 Negro

pupils requested reassignment to formerly all-white schools

(99a, 180a). Because of the shift in the assignment of

pupils there was a corresponding reduction in the allot

ment of teachers at the Negro schools and an increased

allotment of teachers in the white schools (60a, 101a, 161a-

177a, 415a-421a). Plaintiff Wall, although initially favor

ably recommended by her Principal and the Superintendent

and approved for employment for the 1965-66 school year

by the School Board (206a, 267a, 323a), was subsequently

advised by her Principal that due to the reduction in the

6

allotment of teachers at her school she had “been selected

as one of the three teachers, who will not receive a con

tract at this time” (214a), with admittedly no comparison

of her qualifications with other teachers in the system

(314a, 458a, 66a, 82a).

Applicants for teaching positions in defendant’s School

System have generally submitted applications to the var

ious principals or to the Superintendent (365a, 381a, 403a-

405a, 57a). Applications submitted to the Superintendent

have been filed separately according to race, “ for the con

venience of the principals,” since normally Negro princi

pals “were not interested in white applicants,” and white

principals were not interested in Negro applicants (299a,

302a, 57a). When positions became available, applicants

were interviewed by the various principals or by the

Superintendent and recommended to the School Board for

employment (404a, 407a-408a). Teachers in the school sys

tem were routinely re-employed, without the necessity of

competing with new applicants, upon their indication of

their desire to remain in the system (345a). The defen

dant maintained no written standards or criteria for the

employment, assignment and retention of teachers (409a).

At the close of the 1964-65 school year plaintiff Wall,

who had taught in the Stanly County School System for

thirteen years, expressed her desire to remain in the sys

tem. She was accordingly recommended and approved for

employment for the 1965-66 school year. Due to the trans

fer of Negro students from her school to the formerly all-

white Norwood School, the teacher allotment at her school

was reduced by three (415a) and increased by two at the

Norwood School (416a). No instruction was given to the

principals as to the procedure to follow in case of loss of

teachers, the Superintendent assuming that they would

7

take “ several things into consideration;” nor were the

white principals advised that they could or should employ

Negro teachers who might be affected by the reduction in

the allotment of teachers at Negro Schools (314a, 60a).

Plaintiff Wall was selected as one of several teachers to

be displaced because of her alleged “negative attitude”

which was explained as questioning the programs of her

principal, failing to attend meetings, not following the

rules of her school and being absent from school (242a-

246a, 274a-278a). No comparison, however, was made of

the plaintiff’s qualification or alleged faults with other

teachers in the system (314a, 66a, 82a), and despite these

alleged faults, she was nevertheless recommended for em

ployment. Her Principal testified that this was because he

“didn’t have any other applicants for the position” (284a),

although he admitted having several such applications

(283a, 286a, 455a). The Superintendent sought to explain

his recommendation of the plaintiff on the ground that

they feared hiring new teachers (452a), although approxi

mately fifty new white teachers were hired for the 1965-66

school year, many in positions the plaintiff was qualified

to fill and could have filled were it not for defendant’s'

racial policies (104a-131a, 181a-199a, 178a). The record

is clear, as conceded by the District Court (82a), that had

not the Negro students transferred to formerly all-white

schools and had there been no reduction in the allotment

of Negro teachers, the plaintiff would have been employed,

her alleged faults notwithstanding.

On April 15, 1966, the School Board adopted a plan to

govern employment and assignment of teachers and school

personnel which generally adopts the pattern followed by

the defendant in the past and further provides that staff

and professional personnel will be employed and assigned

without regard to race (216a-232a, 436a-437a, 504a).

8

The District Court, in dismissing the complaint, found

the new plan constitutionally acceptable, and that the de

fendant, in dismissing the plaintiff, did not act arbitrarily

or capriciously and was not required to accord the plaintiff

the same objective comparison and consideration which

this Court and others have held that Negro teachers simi

larly affected were entitled.

Questions Involved

1

Where a School Board, in attempting to desegregate its

school system, reduces the number of teachers at its Negro

schools and increases the number of teachers at its white

schools because of the transfer of Negro students to the

formerly all-white schools, may Negro teachers thereby af

fected be denied objective comparison of their qualifications

and equal consideration for employment with other teachers

in the school system, Negro and white, in the School Board’s

selection of the teachers to be displaced when new white

teachers are hired to fill the positions in the formerly

all-white schools?

2

Where, upon a showing of a long-established policy of

racial employment, assignment and dismissal of teachers,

a School Board, following the filing of suit and a few days

before the case is heard, adopts a plan which provides

generally that race will not be considered in the future

but which nevertheless allows for such consideration, and

no actual or material steps have been taken by the Board

to implement its plan, are Negro teachers affected by the

Board’s policies and practices entitled to injunctive relief?

9

ARGUMENT

Preliminary Statement

This Court, on two previous occasions, Chambers v.

Hendersonville City Board of Education, 364 F.2d 189

(4th Cir. 1966) and Franklin v. County School Board of

Giles County, 360 F.2d 325 (4th Cir. 1966), reversing 242

F. Supp. 371 (W. D. Va. 1965), has considered the startling-

decimation of Negro teachers resulting from attempted

desegregation of school systems. As Negro students ob

tain transfers to formerly all-white schools and formerly

all-Negro schools are closed or integrated, Negro teachers

in increasingly large numbers have been summarily dis

missed rather than transferred along with the Negro stu

dents or employed and assigned without regard to race,

thus prompting concern from the President of the United

States,1 revised rules of the Department of Health, Edu

cation and Welfare2 and the subject of intensive studies

1 Speech, N. E. A . Convention, July 2, 1965, New York. The President

stated:

“For you and I are both concerned about the problem of the dis

missal of Negro teachers as we move forward— as we move forward

with the desegregation of the schools of America. I applaud the

action that you have already taken.”

“For my part, I have directed the Commissioner of Education to

pay very special attention in reviewing the desegregation plans, to

guard against any pattern of teacher dismissal based on race or

national origin.”

2 U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Revised State

ment of Policies for School Desegregation Plans Under Title Y I of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 [hereinafter referred to as Revised Rules] :

Section 181.13(a) Desegregation of Staff. The racial composition

of the professional staff of a school system, and of the schools in

the system, must be considered in determining whether students are

subjected to discrimination in educational programs. Each school

system is responsible for correcting the effects of all past discrim

10

by national groups.3

Here, the School Board, following the transfer of ap

proximately 300 Negro students from formerly all-Negro

to formerly all-white schools, reduced the teacher allot

ment at the Negro schools with no advice to the Negro or

white principals of the procedure to follow in selecting the

teachers to be displaced. No comparison was made of the

teachers in the system. No consideration was given the

Negro teachers affected for positions in the formerly all-

white schools. Their jobs had simply gone out of existence

and new white teachers were hired to fill the positions in

the white schools (104a-131a, 181a-199a, 178a).

inatory practices in the assignment of teachers and other professional

staff.

Section 181.13(h) New Assignments. Race, color, or national origin

may not be a factor in the hiring or assignment to schools or within

schools of teachers and other professional staff, including student

teachers and staff serving two or more schools, except to correct the

effects of past discriminatory assignments.

Section 181.13(c) Dismissals. Teachers and other professional

staff may not be dismissed, demoted, or passed over for retention,

promotion, or rehiring, on the ground of race, color, or national

origin. In any instance where one or more teachers or other pro

fessional staff members are to be displaced as a result of desegre

gation, no staff vacancy in the school system may be filled through

recruitment from outside the system unless the school officials can

show that no such displaced staff member is qualified to fill the

vacancy. I f as a result of desegregation, there is to be a reduction

in the total professional staff of the school system, the qualifications

of all staff members in the system must be evaluated in selecting the

staff members to be released.

3 See National Education Association, Washington, D. C., “Report of

Task Force Appointed to Study the Problem of Displaced School Per

sonnel Related to School Desegregation and the Employment Studies of

Recently Prepared Negro College Graduates Certified to Teach in 17

States, December 1965 [hereinafter referred to as N. E. A . R eport];

Ozman, “ The Plight of the Negro Teacher,” The American School Board

Journal, pp. 13-14, September, 1965.

11

This pattern follows that found by NEA Study to be

taking place all over the South:4

“ Concern with faculty integration is becoming acute

because of current practices. Typically, whenever

twenty or twenty-five Negro pupils are transferred

from a segregated school, the Negro teacher left with

out a class is in many cases dismissed rather than

being transferred to another school with a vacancy.

• • •

“As has been demonstrated, ‘white schools’ are

viewed as having no place for Negro teachers. As a

result when Negro pupils in any number transfer out

of Negro schools, Negro teachers become surplus and

lose their jobs. It matters not whether they are as

well qualified as, or even better qualified than, other

teachers in the school system who are retained. Nor

does it matter whether they have more seniority. They

were never employed as teachers for the school sys

tem—as the law would maintain—but rather as teach

ers for Negro schools.”

The deprivation of constitutional rights threatened by

such dismissals have been carefully reviewed by this Court

and in each instance the burden has been placed upon

school authorities to show by clear and convincing evi

dence that their conduct was consistent with due process

and equal protection of the law. Franklin v. County School

Board of Giles County, supra; Chambers v. Hendersonville

City Board of Education, supra; see also Smith v. Board

of Education of Morrilton School District No. 32, 365 F.2d

770 (8th Cir. 1966); Christmas v. Board of Education of

Harford County, 231 F. Supp. 331 (D. Md. 1964). Viewed

in light of the principles established in the above cases,

4 N. E. A . Report, p. 13.

12

the instant case clearly establishes that the School Board’s

practices and conduct were inconsistent with plaintiffs’

rights under the Constitution and that the District Court

erred in refusing’ to grant plaintiffs injunctive relief as

prayed.

I

The School Board’s Dismissal of Plaintiff Wall and

Others of Her Class, in Attempting to Desegregate Its

System, With No Consideration or Comparison of Their

Qualifications With Other Teachers in the System,

While Hiring New White Teachers to Fill Positions in

White Schools Constituted a Clear Denial of Due Proc

ess and Equal Protection of Law, Entitling Them to

Reinstatement and Damages.

It is clear that the Fourteenth Amendment forbids dis

crimination on the basis of race by a public school system

with respect to the employment, assignment and retention

of teachers and other school personnel. Chambers v. Hen

dersonville City Board of Education, supra; Franklin v.

County School Board of Giles County, supra; Wheeler v.

Durham City Board of Education, 363 F.2d 738 (4th Cir.

1966); Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School

District No. 32, supra; Bradley v. School Board of the

City of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103, reversing 345 F.2d 310

(4th Cir. 1965); Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ; Kier v.

County School Board of Augusta County, 249 F. Supp. 239

(W. D. Va. 1966); Revised Rules, Section 181.13(c). It is

equally clear that the Fourteenth Amendment forbids de

nial by a school board or other public agency of employ

ment to teachers and other public servants on some frivo

lous, arbitrary or other ground which fails to accord due

13

process. Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S.

278; Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488, 495-96; Schware v.

Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232; Slochoiver v. Board

of Education, 350 U.S. 51; Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S.

183; Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir. 1966);

Rackley v. School District Number 5, Orangeburg County,

------ F. Supp. ------ (Civil No. 8458, D. S. C., 1966). De

fendant’s practices here in dismissing plaintiff Wall and

Negro teachers of her class were violative of their rights

to due process and equal protection of the law.

A. In an homogeneous school system, where teachers

are and may be assigned among the various schools de

pending on needs of the system, as the Superintendent

testified his school system to be (430a-431a, 435a, 459a),

it is patently violative of the rights of Negro teachers to

limit their consideration for employment to the Negro

schools. Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Edu

cation, supra; Franklin v. County School Board of Giles

County, supra. Following the reduction in the allotment

of teachers at the Negro schools, Negro teachers were

displaced with no comparison whatever of their qualifica

tions with other teachers in the school system. Moreover,

there was here not even the semblance of evaluating “their

right to continue employment in terms of the vacancies

then existing in the other schools in the system.” Franklin

v. County School Board of Giles County, 242 F. Supp. 371,

374 (W. D. Va. 1965), reversed, 360 F.2d 325 (4th Cir.

1965). Approximately 50 new white teachers were hired

to fill the positions in the white schools which the Negro

teachers were qualified to fill. In view of the practice fol

lowed by the defendant, with Negro and white teachers

being assigned to separate schools on the basis of race,

the defendant’s failure to fairly and objective appraise

the Negro teachers for all positions for which they were

qualified permits no conclusion other than they were “dis

14

charged because of their race.” Franklin v. County School

Board of Giles County, supra; Chambers v. Hendersonville

City Board of Education, supra; Smith v. Board of Edu

cation of Morrilton School District No. 32, supra. See

also Revised Rules, Section 181.13(c). In addition, such

appraisals were to be fairly, objectively and equally ap

plied throughout the system to Negro and white staff

members. Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, supra;

Johnson v. Branch, supra; Bradley v. School Board of the

City of Richmond, 317 F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963); Green v.

School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F.2d 118 (4th Cir.

1962). Had that been done here, the evidence clearly

shows that plaintiff Wall and others of her class possessed

far superior qualifications to many of the white teachers

retained or newly hired in positions the plaintiff and mem

bers of her class were qualified to fill.5

As a basis for the dismissal of plaintiff Wall, defen

dant has asserted her alleged “negative attitude.” The

District Court found this sufficient to deny to her the con

stitutional rights to fair and objective consideration and

comparison with other teachers in the school system (84a).

These alleged faults, however, were considered material

by the defendant only after it became necessary to reduce

the Negro teachers at the plaintiff’s school and after her

principal and the Superintendent had favorably recom

mended her and the defendant had approved her employ

ment for the 1965-66 school year. Moreover, with no com

parison of the plaintiff’ s qualifications and of her alleged

faults, no fair and objective determination could be made

by the defendant as is clearly required by the teachings

of this Court. Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of

5 See 118a-131a, where many teachers held Emergency B, Primary B

or no Certificates at all. Plaintiff W all had a Grammar Graduate Cer

tificate, with 13 years experience in the Stanly County School System.

15

Education, supra; Johnson v. Branch, supra; Franklin v.

County School Board of Giles County, supra, and see par

ticularly Note 3, requiring that the Board objectively dem

onstrate that it would not have retained the teacher in

volved “under any circumstances.” As the District Court

here found, had there been no transfer of Negro students

to the white schools, and had there been no reduction in

the allotment of teachers at her school, plaintiff Wall

“would have been re-employed for the school year 1965-66”

(82a). Clearly, therefore, the asserted basis here for not

retaining plaintiff is to be given no weight. It could not

properly be a sufficient basis where, as here, the defendant

has failed to consider her for other positions in the sys

tem and to fairly, objectively and without discrimination

appraise her qualifications with “ all staff members in the

s y s t e m Otherwise, the constitutional principles clearly

established in the above cited cases would become sterile

pronouncements without meaning or force. Johnson v.

Branch, supra.

The evidence here further shows that Frederick Wel-

borne was denied objective and fair comparison with other

teachers in the system prior to the determination to deny

him employment (235a-237a, 241a-242a, 246a-247a). He

too had been recommended for employment and his em

ployment approved for the 1965-66 school year (211a).

He too was to be dismissed following the reduction in the

allotment of teachers at his school. It is true that he

obtained other employment fearing the loss of Negro

teachers in the system (280a). The District Court did not

consider it material that no objective appraisal was made

since Welborne had obtained employment elsewhere (85a),

but the failure initially to fairly and objectively consider

him for any position in the system without regard to race

further corroborates defendant’s racially discriminatory

16

practices with respect to plaintiff and others of her class.

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, supra;

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

supra; Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford

County, supra.

B. Plaintiff Wall is entitled to an order requiring her

reinstatement and a determination of her damages. Cham

bers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education, supra;

Johnson v. Branch, supra; Franklin v. County School Board

of Giles County, supra; Smith v. Hampton Training School

for Nurses, 360 F.2d 577 (4th Cir. 1966); Rackley v. School

District Number 5, Orangeburg County, supra. The evi

dence here clearly establishes that the plaintiff was dis

missed in a manner inconsistent with her rights to due

process and equal protection of the law. She is thus en

titled to an effective remedy as established by this Court

in the above cases. See also Service v. Dulles, 354 U.S.

365; Vitarelli v. Seaton, 359 U.S. 353; Greene v. McElroy,

360 U.S. 474, 491-92; Wickersham v. United States, 201

U.S. 392.

17

II

Plaintiffs Are Entitled to An Order Enjoining Fur

ther Racial Employment, Assignment and Dismissal of

Teachers and School Personnel.

The responsibility for eliminating past racial assign

ments of teachers and school personnel and instituting an

effective plan and practice of non-racial employment is

that of the defendant Board. Chambers v. Hendersonville

City Board of Education, supra; Wheeler v. Durham City

Board of Education, supra; Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966);

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County, supra;

Revised Rules, Section 181.13.6 Defendant’s long-estab

lished practice of racial employment and assignment of

teachers is clear (433a, 56a, 62a). All Negro teachers and

school personnel have been assigned to Negro schools and

all white teachers and school personnel assigned to white

schools. In January 1966, defendant employed one Negro

teacher at North Stanly, a formerly all-white school. In

April 1966, the defendant adopted a plan which contained

a provision that staff and professional personnel shall be

employed and assigned to and within schools without re

gard to race, color or national origin (219a). The plan

further provided that teachers were to indicate whether

they would teach in an all-white, all-Negro or integrated

school (255a) and the Superintendent testified that he

would honor such indications (437a-441a). No other steps

had been taken by the Board or planned (444a) to correct

or eliminate the Board’s racial policies. The District Court

denied injunctive relief reasoning that the plan was a

6 See also N. C. Gen. Stat. §$115-58, 115-59, 115-72, expressly placing

the responsibility for the employment and assignment of teachers upon

school boards.

18

sufficient corrective.7 The District Court, however, clearly

erred. In view of the long history of racially discrimina

tory practices by the Board, still in the process of attempt

ing to desegregate, and with no more showing by the

Board that one Negro teacher had been assigned to a

formerly all-white school, injunctive relief as prayed by

the plaintiffs should have been granted. Brooks v. County

School Board of Arlington County, 324 F.2d 303 (4th Cir.

1963); Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

317 F.2d 429 (1963). See particularly Chambers v. Hen

dersonville City Board of Education, supra, where the

School Board had advanced much further in integrating

its staff and this Court nevertheless held that the plaintiffs

as a class were entitled to injunctive relief and that the

Court should retain jurisdiction “until the transition to a

desegregated faculty is completed.” Id. at 193.

7 The District Court further held that such considerations were not

per se impermissible, citing Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington

County, 357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) and Olson v. Board of Education

of Union Free School District No. 12, 250 F . Supp. 1000 (E . D. N. Y .

1966), and reasoning further that the constitution does not forbid volun

tary associations, citing Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

345 F.2d at 316. This, reasoning, however, ignores the necessity for in

junctive relief. In both Wanner and Olson the School Board had adopted

affirmative policies to promote integration. The Court simply held that

race in such instances were permissible consideration. Certainly, here the

School Board advances no contention that its purpose is to promote inte

gration but rather the opposite as is clearly established by the record.

Moreover, the District Court’s reliance on Bradley not only permits but

encourages the very practice reproved by this Court in Wheeler V.

Durham City Board of Education, supra, the perpetuation of racial em

ployment and assignment practices by school boards. Certainly, where

teachers are involved as plaintiffs who are adversely affected are entitled

to injunctive relief. Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

supra.

19

CONCLUSION

Plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court reverse the

holding of the District Court and remand the case with

instructions requiring both the reinstatement of plaintiff

Wall and the determination of her damages resulting from

her wrongful discharge and the issuance of an injunction

restraining the defendant from further consideration of

race or color in the employment, assignment and dismissal

of teachers and professional personnel. The plaintiffs fur

ther pray that if a reduction in teacher force in defendant’s

system is required, that defendant be ordered to apply the

same standards or criteria to all teachers and applicants,

and after such appraisal, should the plaintiff or any mem

ber of her class be refused employment, the defendant be

required to establish by clear and convincing evidence that

those denied employment were accorded due process and

equal protection of the law.

Respectfully submitted,

Conrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

J. L evonne C hambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 219