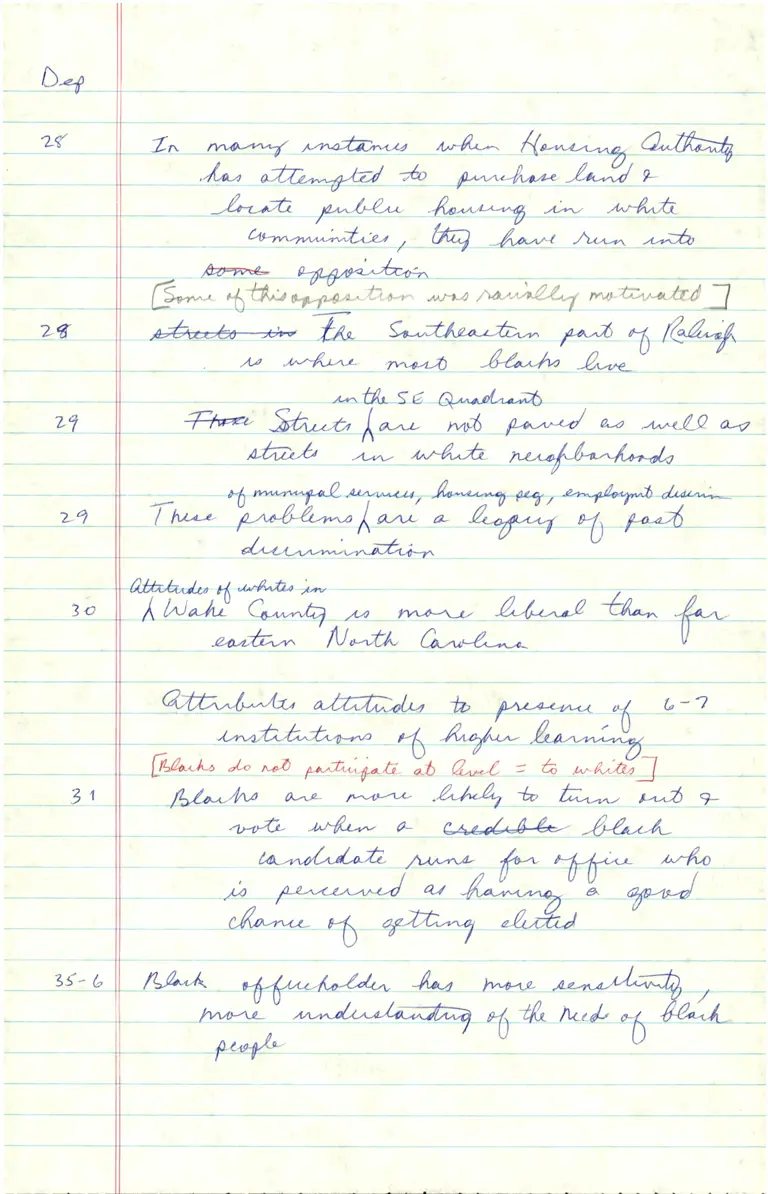

Attorney Notes on Vernon Malone 2

Working File

January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Attorney Notes on Vernon Malone 2, 1983. 283e2f57-df92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/32d50255-941b-4ff8-818b-7fee2a6da4dc/attorney-notes-on-vernon-malone-2. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

’ZS/

W mMWm

W

[MW Ifisz—W WWWJ

2g

aézeéa 7‘,” fly. S;4W£a1./t‘m MM U/ZM

Mfll (g QMJAAADé

2?

W WWW

U

7,9

TAM W7AW¢W96M

W I

0147A£ 1 #154t'viw

35

WNVMW

W am "[2; W 41 (9-7.1.

Wot/AW U

fiaLLOAOMJ Mgm%1afi¢ Q:£ :zz1waA27

WWWWfim/ng,

anal xwfluu ¢- é~uéafiévwxfléujL

MWW MUUW

Mkémm ”

35’é

W mem'

fiwwu. UAomdmeEZZZE1m§fialkwbo¢gzufl,

A_A_1_J____________+_g_11___+#1111 J - A -