Riverside v Rivera Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1985

69 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Riverside v Rivera Brief Amicus Curiae, 1985. fa369d80-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/32d94cfa-c2a8-4aa7-93f5-d719553a5f67/riverside-v-rivera-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

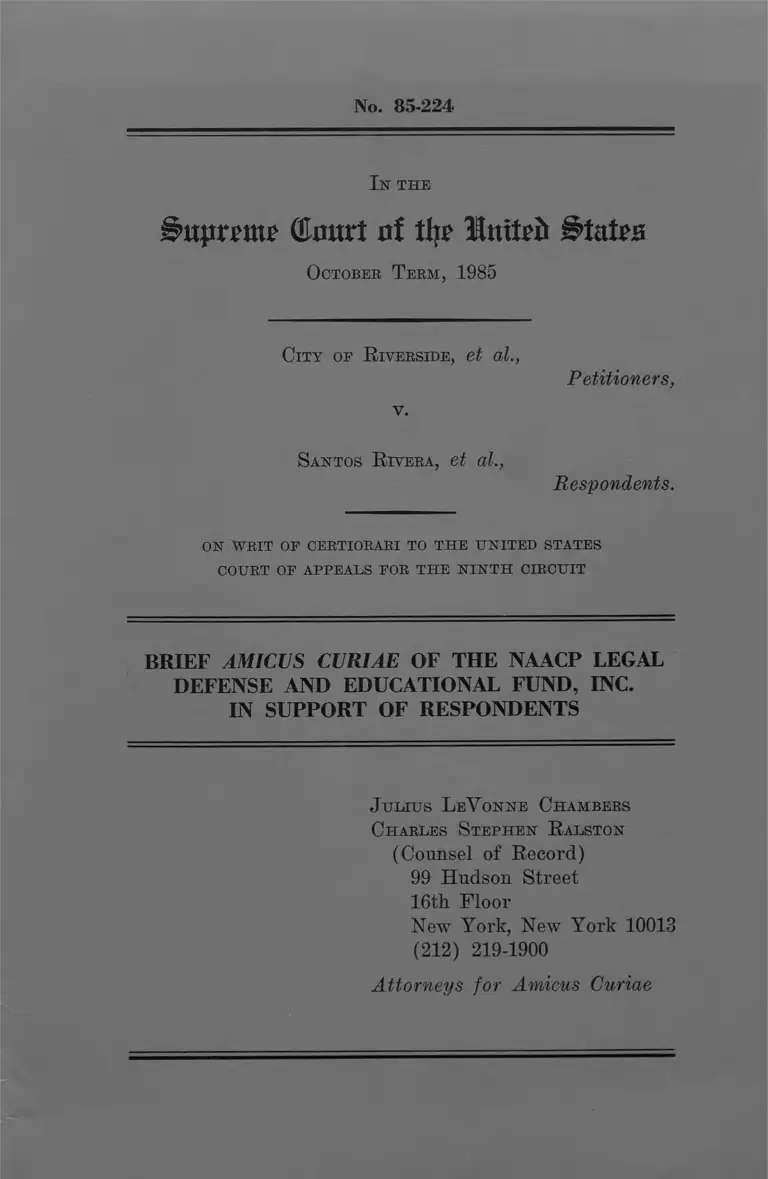

No. 85-224

In t h e

(Emtrt of tljp llntt^ States

O ctober T erm , 1985

C ity of R i v e r s i d e , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

S antos R ivera, et al.,

Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U N ITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR T H E N IN T H CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

J ulius L eV onne Chambers

C harles S tephen R alston

(Counsel of Record)

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Question Presented

Whether attorneys' fees properly

calculated on the basis of reasonable

hours and rates should be reduced solely

on the basis of the size of the monetary

recovery?

i

Table of Contents

Question Presented ................... i

Table of Contents..................... ii

Table of Authorities................. iii

Interest of Amicus ................. 1

Summary of Argument ................. 5

Argument ........................... 6

I. Calculating Fees As A

Percentage of A Monetary

Recovery Is Improper in

A Civil Rights Case . . . 6

II. A Proportionality Rule Is

Contrary to Clear

Congressional Intent . . . 18

Conclusion......................... 24

Appendix

ii

Page

Cases:

Bivens v. Six Unknown Aqents,

403 U.S. 388 (1971)........ 15

Bob Jones University v. United

States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983) . 24

Brandon v. Holt, U.S. ,

83 L.Ed.2d 878 (1985) . . . . 11

Butz v. Economou, 438 U.S. 478

( 1978)............... 1 1

Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247

( 1978)............... 12

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d

880 (D.C. Cir. 1980) . . . . 10

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496

( 1939)............... 12

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S.

424 ( 1983)........... 16

Johnson v. Click, 481 F . 2d

1028 (2d Cir.), cert, denied

sub nom. Employee-Officer

John, Number 1765 Badqe No. v.

Johnson, 414 U.S. 1033 (1973) 10

Los Anqeles v. Lvons, 461 U.S.

95 ( 1983) .'......... 13

Table of Authorities

i i i

Monell v. Dept, of Social

Services, 436 U.S. 658

( 1978)................... 1 1

New York Gasliqht Club v. Carey,

447 U.S. 54 ( 1980)...... 17

Patsy v. Florida Bd. of Reqents,

457 U.S. 496 (1982) . . . . 23

Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547

( 1967)..................... 14

Pulliam v. Allen, __ U.S. ____,

80 L.Ed.2d 565 (1984) . . . . 11

Ruiz v. Estelle, 550 F.2d 232

(5th Cir. 1977)............ 1 1

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232

( 1974)..................... 14

Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. ___,

85 L. Ed. 2d 1 ( 1985)........ 12

Vasquez v. Hillery, ___ U.S. ___,

54 U.S.L.W. 4068 ..........

(January 14, 1986 .......... 23

Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S. 308

(1975)..................... 13

Statutes;

42 U.S.C. $ 1983 ................. 3

42 U.S.C. § 1988 ................. passim

Legal Fee Equity A c t .......... 22, 23

iv

S. 28 02, 98t.h Cong., 2d

Sess. (1984) ...............

S. 1580, 99th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1985) ...............

Other Authorities;

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (Sept. 25, 1976) . 13

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (June 29, 1971) . . .

"Civil Rights Attorney's Fees

Awards Act of 1976: A

Report to Congress"

(National Association of

Attorneys General, 1984) . .

Chambers and Goldstein, "Title

VII at Twenty: The

Continuing Challenge,"

The Labor Lawyer, 235,

255-58 (1985) ............

"Counsel Fees In Public

Interest," A Report by The

Committee On Legal Assistance,

39 The Record of the

Association of the Bar of the

City of New York 300 (1984) .

Daily Labor Report, Jan. 9,

̂1986 (BNA) .................

Legal Fee Fquity Act: Hearing

Before the Subcommittee on the

Constitution of the Senate

Judiciary Committee ̂ (98th Cong.

2d Sess., 1984).................

23

, 14

14

18

18

4, 8

16

22

21

v

Municipal Liability Under 42 U.S.C.

$ 1983: Hearings Before the Sub-

committee on the Constitution of the

Senate Judiciary Committee, 97 Cong.

1st Sess. ( 1981 ) .......... 19, 20

No. 85-224

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

CITY OF RIVERSIDE, et al.

Petitioners,

v .

SANTOS RIVERA, et al.

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the

Ninth Circuit

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

INTEREST OF AMICUS1

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc. has been in the fore-

Letters consenting to the filing of this

brief have been lodged with the Clerk of

Court.

1

2

front of civil riohts litigation for many

years. As part of that effort we have had

a long standing interest in the award of

attorneys' fees adeguate to ensure an

appropriate level of private enforcement

of the civil rights statutes. Thus, we

have appeared as counsel or as amicus

curiae in most of the leading civil rights

2attorneys' fees cases.

In the present case, in addition to

the interest of the Legal Defense Fund

itself, we wish to present to the Court

the interests and concerns of the private

civil rights bar. The Legal Defense Fund,

as are other organizations, is dependent

on the continuing collaboration of

private attorneys in bringing civil rights * i

E*»9 • r Newman v. Piggie Pack Enterprise,

ino • r 3 9 0 U.S . 400 ( 1968); Bradley vT

School Bd. of City of Richmond, 416 U.S.

696 (1974); Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678

(1978); Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424

(1983); Johnson v. Georqia Highway Express

Co., 488 F. 2d 714 (5th C'ir. 1974).

3

cases under 42 IJ.S.C. § 1983 and the

various other civil rights statutes. Our

near.lv 200 cooperating attorneys are

primarily single practitioners and

attorneys in small firms. Unlike attor

ney's in larqe firms, they cannot depend

on major commercial clients to support

their pro bono activities. And, unlike

lawyers who specialize in personal injury

litigation, those who practice civil

rights law cannot realistically depend

upon a continuing flow of cases in which

substantial fees may be taken from the

recovery by the plaintiffs as an agreed

upon percentage. To a very large degree,

they depend upon the award of fees

adequate to compensate them for the time

actually expended on the cases they win.

It was precisely for these attorneys

and their particular type of practice that

Conaress enacted the various fee statutes.

4

If the arguments of petitioners and their

amici are accepted by this Court, these

attorneys will, by and larqe, be driven

out of the practice of civil rights law.

The private enforcement of civil riahts

cases will be undermined and the enforce

ment of constitutional rights will be left

almost exclusively to the pro bono efforts

of a few large firms and to a few public

interest oraanizations, which employ less

3

than 100 attorneys altogether.

We submit that such a result, however

much desired by petitioners and their

amici , would be totally contrary to the

intent of Congress.

See "Counsel Fees In Public Interest

Litigation," A Report by The Committee On

Legal Assistance, 39 The Record of the

Association of the Bar of the Citv of New

York 300, 325 (1984).

5

SUMMARY OP ARCUMHNT

T .

Civil riahts cases, even those in

which there is a monetary recovery, cannot

simplisticly be equated to continqent fee

tort limitation or other types of commer

cial practice. Because of the large

public issues and difficult legal ques

tions involved, civil rights cases often

require a substantial investment in time.

Yet recoveries are typically small and

uncertain; delays in payment are common

place, in part because of litigation

tactics of movernment and defense attor

neys. The adoption of a proportionality

rule would, therefore, have a devastatinq

effect on the ability of plaintiffs to

brinq these cases.

6

Congress clearly did not intend that

fees be calculated as a percentage of a

monetary recovery. Repeated attempts to

have the fees acts amended to include such

a provision have been rejected by Con

gress. Therefore, the Court should not

adopt the rule urged by petitioners and

their amici.

ARGUMENT

I.

CALCULATING PEES AS A PERCEN

TAGE OF A MONETARY RECOVERY IS

IMPROPER IN A CIVIL RIGHTS

CASE

1. In an amicus brief filed earlier

this term, we have described the nature of

civil riqhts practice and why it cannot

simplisticly be equated to ordinary

commercial litigation. See Brief Amici

Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., et al., in Evans

II.

7

v. Jeff P., No. 8 4-1288, at Q-14. We

respectfully refer the Court to that

discussion. Similarly, the parallel

sought to be drawn here by petitioners

and their amici between continoent fee

tort litiqation and civil riqhts litiga

tion is totally inapposite.

If civil riqhts litigation were like

tort litiqation, no fee statute would have

been necessary. Negligence cases can be

extraord inarily lucrative. The risk of

losing a certain percentage of cases is

made up by larae fee recoveries in others.

Further, the litiqation of such cases is

handled in the same manner as is other

ordinary commercial litigation. Thus,

both parties are represented by an

established bar that seeks reasonable

compromise and the speedy disposition of

cases

8

The reality of civil rights litiga

tion is far different. Defendants'

attorneys, particularly when they repre

sent crovernmental agencies, do not see

civil rights litigation as ordinary cases

that should be handled in an ordinary

fashion. To the contrary, often they take

umbrage over the very fact that a lawsuit

is filed. A common litigation tactic of

defendant's counsel is to fight a case to

4

the bitter end.

Moreover, as discussed fully in

respondents' brief, Congress was fully

aware both of the drawn out and protracted

nature of civil rights litigation as well

as the overwhelming inequality of re

sources between plaintiffs and defendants.

City, county, and United States Attorneys,

attorneys general, and aaency counsel, as

well as the investigative and support

4 See op cite supra n.3, at 322-23.

9

staff of governmental agencies, are pitted

against one or a handful of, at best,

middle income plaintiffs and the few

attorneys willinq to take on such odds.

The fact of the matter is that local and

state governments are well eauipped to

protect their rights.

2. To the extent that public funds

are unduly expended on fee awards, it has

been our own experience that this is more

often caused by the litigation tactics of

Government defense attorneys than by the

actions of the plaintiffs. The present

case provides a vivid example. It should

have been settled early with a full

apoloav to plaintiffs and a reasonable

monetary settlement. Instead it was

fouaht with public funds in an unsuccess

ful attempt to defend indefensible actions

of police officers. As the Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia noted

10

in Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880, 904

(D.C. Cir. 1980) (en banc), it is a

qovernment's right to defend a case in any

way it chooses, but once it has decided to

defend a case to the death, it may not

then be heard to complain when it is faced

with a reasonable attorney's fee caused by

its own litigation tactics.

Even in cases where the defense has

been reasonable, the nature of civil

rights claims often results in extended

litigation. Facts are often difficult

to gather; for example, even the identity

of the appropriate defendants may be

unknown or difficult to ascertain, see,

e .g . , Johnson v. Click, 481 F.2d 1028 (2d

Cir.), cert. denied sub nom. Em

ployee-Officer John, No. 1765 Badge

Number, 414 U.S. 1033 (1973), a matter

rarely in dispute in ordinary tort

litigation. Often, access both to the

v i t a l information underlyina the suit and

to the plaintiffs themselves is controlled

by the defendants. See, e ,g. , Ruiz v.

Estelle, 550 F.2d 238, 239 (5th Cir. 1977)

("The record discloses that in response to

their participation in this litioation,

these inmates have been subjected . . . to

threats, intimidation, coercion, punish

ment, and discrimination, all in the face

of protective orders. . . ."). Moreover,

uncertainties in the law, particularly

regardinq the liability of government

5

agencies and personnel acting in their

6

official capacities, may lead to multiple

See Monell v. Dept.»of Social Services,

436 U.S. 658 ( 1°78); Brandon v. Holt,

U.S. ____, 83 L.Ed.2d 878 (1985).

See, e.n., Pulliam v. Allen, U.S.

____, 80 I,.Ed. 2d 565 ( 1984); Butz v.

Economou, 438 U.S. 478 ( 1978); Pierson v.

Rav, 386 U.S. 547 (1967).

12

appeals. Under petitioner's rule all such

work -- no matter how reasonable or

necessary -- would, in effect, go uncom

pensated .

3. The inappropriateness of a

proportionality rule also follows from the

fact that, for a variety of reasons, the

availability of monetary and even injunc

tive relief is limited in many civil

rights cases. As long ago as Hague v.

CIO, 307 U.S. 496 ( 1939), this Court

recognized that tortious invasions of

constitutional rights were, by their

nature, difficult to measure in monetary

terms. Under Carey v. Piphus, 435 U.S. 247

(1978), a plaintiff may only be able to

obtain minimal or only nominal damages. At

the same time, a plaintiff who has

suffered a past injury may not have

7 For example, there were two appeals in

Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. ____, 85

L.Ed.2d 1 (1985), before the case reached

this Court, and further proceedings will

be required before judgment is entered.

7

13

standing to obtain injunctive relief if,

as in this case, a repetition of the

unconstitutional conduct is purely

speculative. -Los- Angeles v. Lyons, 461

U.S. 95 (1983).

Congress was aware of these doctrines

and their effect on the economic viability

of civil rights litigation. Accordingly,

it observed that

While damages are theoretically

available under the statutes

covered by [§ 1988], it should

be observed that, in some cases,

immunity doctrines and special

defenses, available only to

public officials, preclude or

severely limit the damage

remedy. Consequently, awarding

counsel fees to prevailing

plaintiffs in such litigation is

particularly important and

necessary if Federal civil and

constitutional rights are to be

adequately protected.

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d

Sess., at 9 (Sept. 15, 1976) (citing Wood

. Stricklandv f 420 U.S. 308 (1975);

14

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 ( 1974);

and Pierson v. Bay, 386 U.S. 547 (1967))

8

(footnote omitted; emphasis added).

But consider the result of a decision

ignoring the implications of this legisla

tive history and imposing a rule making

fees proportional to the amount in

damages. Inevitably, civil actions to

redress certain types of constitutional

violations will not be brought solely

because they are unlikely to generate

damage awards large enough in support a

proportional fee award "adeauate to

attract competent counsel." S. Rep. No.

94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess., at 8 (June

26, 1976); H.R. Rep. Mo. 94-1558 at 9. Not

only will Conaress's clearly expressed

purpose be subverted, but also the

The report aoes on to state that in a

third class of cases, those in which "only

injunctive relief is sought . . . pre

vailing plaintiffs should ordinarily

recover their counsel fees." Id.

15

hope that damage suits can be a viable

means to deter fourth amendment viola

tions, see Bivens v. Six Unknown Agents,

403 U.S. 3 8R-, 411 (1971) (Buraer, C.J.,

dissenting), will be frustrated; the only

persons with a meaningful remedy will be

criminal defendants.

The reality is plain. The Bill of

Rights is not self-executing; without

plaintiffs there will be no enforcement;

without attorneys financially able to

bring cases there will be no plaintiffs.

The government's assertion that there are

many attorneys who would take on these

difficult and time-consuming cases in the

expectation of a one-third fee from a

$33,000 judgment is not only belied by the

facts of this case — there were no local

attorneys willing to take it — but can

only be described as a fantasy. It

certainly has no relation to the real

16

world of civil rights practice as the

Legal Defense Fund and its cooperating

9

attorneys experience it every day, or as

Congress viewed it when it considered and

passed what is now § 1988.

4. The arguments of the petitioner

and its amici, particularly those of the

United States, are totally contrary to

congressional intent and the decision of

this Court in Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461

U.S. 424 (1983). The qovernment advances

a number of arguments that it now states

would limit the proportionality rule to

those cases where the only relief sought

The Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission has an entirely different view

than that of the Solicitor General

concerning the impact of a proportionality

rule on the private bar and the enforce

ment of the civil rights acts. Indeed, it

urged that the United States support the

position of respondents in this case. Its

memorandum to the Solicitor General was

printed in full in the Daily Labor Report

of January 9, 1986 (BNA), at pp. E-1 to

E—5. For the convenience of the Court, we

have reproduced the memorandum on the

appendix to this Brief.

17

or recovered is money damages in the

nature of a tort recovery. But it is hard

to see how or why the rule they seek can

he so limited in the face of similarly

worded and intentioned statutes. Bee New

York Gaslight Club v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54,

70-71 n. 9 (1980). Thus, in individual

Title VII actions, defendants will soon

assert that fees should be limited to a

proportion of the backpay recovery. Such

a rule would, of course, be devastating to

Title VII. Fven for a case involving an

upper level iob, a recovery of backpay for

a person denied a promotion is unlikely to

exceed 820,000. Particularly when the

defendant is a oovernment employer (and we

speak from 14 vears of experience in

litinatino Title VII cases against the

federal government), the achievement of

that result may take hundreds, if not

thousands, of attorney hours.

18

We, therefore, are able to state

without ciualif ication that a rule of

proportionality would have the immediate

and wholly predictable effect of driving

from practice those attorneys who are

responsible for providing representation

to civil rights plaintiffs in the vast

majority of civil rights and Title VII

litigation --single practitioners and

10

attorneys from small firms.

II.

A PROPORTIONALITY RULE IS

CONTRARY TO CLEAR CONGRESSIONAL

INTENT

The respondents' brief sets out fully

and interprets correctly the legislative

history of the 1976 Fees Act. In addi

tion, we wish to bring to the Court's

TIT See Chambers and Goldstein, "Title VII at

Twenty: The Continuing Challenge," 1 The

Labor Lawyer 235, 255-58 (1985).

19

attention the fact that the federal

government and state and local governments

are now attempting to obtain from the

Court through a restrictive interpretation

of § 1988 what they have so far tried but

failed to achieve in Congress. Indeed, so

far they have been unable even to get a

bill out of subcommittee despite five

years of effort.

At least as far back as 1981, an

effort was begun to convince Congress to

amend drastically § 1988 and other fee

acts as they affect government defendants.

Many of the arguments made here — the

alleged burdens on the courts and on local

governments, the purported multiplicity of

frivolous law suits, the unidentified

attorneys getting rich by "windfalls"

-- were made to Congress. See Municipal

Liability Under 4 2 U.S.C. § 1983: Hearings

Before the Subcommittee on the Constitu

20

tion of the Senate Judiciary Committee,

97th Cong. , 1st Sess. (1981), pp. 147-52

and 288-91 (Statement of National Insti

tute of Municipal Law Officers); 524-558

(Statement of National Association of

Attorneys General). Indeed, it was

specifically recommended that the amount

of fees be " incorporat [ed] ... into the

amount being sought in damages." And

that:

If the case carves out a new

area of civil rights law, or if

the case will have a widespread

impact, the prevailing party's

attorney would be entitled to a

larger fee than would be

appropriate where the nature of

the case is similar to a

personal injury case, such as

an injury suffered at the hands

of a police officer. In the

latter instance the judgment

will be of little impact or

interest beyond the parties

directly involved and the fees

awarded should be so limited.

21

Id. at 291. However, the proposed fee

statute failed to be reported out of

committee.

Efforts to have $ 1988 amended

escalated with the issuance of "Civil

Rights Attorney's Fees Awards Act of 1976:

A Report to Congress," by the National

Association of Attorneys General. .See The

Legal Fee Equity Act; Hearing Before the

Subcommittee on the Constitution of the

Senate Judiciary Committee (98th Cong., 2d

Sess, 1984), pp. 237-305. The Report

urged that the Fees Act be amended

specifically to prevent fees that were

allegedly disproportionate to monetary

awards. Given as an example of a case in

which "the amount of fees awarded was

grossly disproportionate to the degree of

success on the merits" was this very case,

Rivera v. City of Riverside, 679 F.2d 795

(9th Cir. 1982). Id. at 272-74

22

This recommendation was incorporated

into The Legal Fee Equity Act (S.2802,

98th Cong., 2d Sess. (1984)), which was

drafted by the United States Department of

Justice. I<3. at 3. Section 6(b)(5) of the

Act, which would have amended not only

§ 1988 but every other federal fees

statute as it applies to federal, state

and local governments, provided that fees

will be reduced when:

[T]he amount of attorneys' fees

otherwise authorized to be

awarded unreasonably exceeds

the monetary result or injunc

tive relief achieved in the

proceeding.

Id. at 24-25. The section-by-section

analysis states that the section is

intended to deal with, for example, "cases

where $100,000 is awarded in attorneys'

fees for a $30,000 judgment." Id. at

124-125.

23

Aqain, the effort to amend the fees

acts got nowhere and the bill died in

subcommittee. The Legal Fee Equity Act

was again introduced in the last session

of Congress (S.1580, 99th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1985)); see 131 Cong. Rec. S.10876 (daily

ed. Aug. 1 , 1985). To date, it has gone

nowhere in either house.

Thus, Congress has refused, despite

persistent attempts by a consortium

representing all levels of government in

this country, to amend § 1988 to incor

porate the very rule urged by petitioners

and their amici. As recently noted in

Vasquez v. Hillery, ____ U.S. ____, 54

U.S.L.W. 4068, 4071-72 (January 14, 1986),

the Court is properly loath to interpret a

statute to accomplish what petitioners

have repeatedly sought but failed to

obtain in Congress. Accord Patsy v.

Florida Bd of Regents, 457 U.S. 496

24

(1982) ; see also Bob Jones University v.

United States, 461 U.S. 574, 599-602

(1983) . In light of the totality of its

legislative history, the Fees Act cannot

reasonably be read to mean that fees are

to be limited to a percentage of a

monetary award in civil rights cases.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the

decision below should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

(Counsel of Record)

99 Hudson Street

16t.h Floor

New York, N. Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

APPENDIX

Memorandum of the

EEOC to the Solicitor

General, Nov. 18, 1985.

EEOC Memorandum to Solicitor General

Charles Fried

Nov. 18, 1985

MEMORANDUM

TO: CHARLES FRIED

Solicitor General

Department of Justice

FROM: JOHNNY J. BUTLER

General Counsel (Acting)

Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission

SUBJECT: Recommendation for participation

as amicus curiae in City of

Riverside v. Rivera, cert,

qranted, 54 U.S.L.W. 3270 (Oct.

22, 1985) (No. 85-224).

The Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission recommends participation in the

above case as amicus curiae in support of

respondents Rivera et a_l. (plaintiffs

below). The brief for petitioner is due

on December 5, 1985, and the brief for

respondent is due on January 4, 1986.

Interest Of The Equal Employment Opportun

ity Commission

This case presents the question of

what are the appropriate standards

governing an award of attorney's fees

under 42 U.S.C. 1988 when the monetary

amount recovered in damages for violations

of constitutional and civil rights is less

than the fees requested.1 Resolution of

this issue will affect substantially

attorney's fee awards under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

2000e et seg. Section 1988 was expressly

modeled on Title VII's fee provision, 42

As discussed infra, this issue was not

expressly raised in the petition for

certiorari. However, subsequent to the

petition, Justice Rehnquist issued an

opinion explaining his grant of a stay and

indicating that the propriety of a fee

award which is disproportionate to the

amount of monetary relief is the central

issue in the case. City of Riverside v.

Rivera , 5 4 U.S.L.Wl 3143 (Rehnquist,

Circuit Justice) (on application for stay)

(Sept. 10, 1985).

3a

U.S.C. 2000e-5(k), and standards developed

in §1988 cases are applied to Title VII.

See, e.g., Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S.

424, 433 n. 7 (1983); S. Rep. No. 94-1011

(1976) at 4-6.

Because Title VII provides solely for

equitable relief, monetary recovery is

limited to amounts owed for back pay.

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(g).2

Accordingly, the monetary recovery in an

individual Title VII case may be relative

ly meager. Petitioners contend, and

Justice Rehnquist's opinion on the stay

application suggests he may agree, that an

award of fees significantly larger than

The courts have held that compensatory and

punitive damages are not available under

Title VII. See Patzer v. Bd. of Regents

of Univ. of Wise., 763 F.2d 851, 854 n. 2

(7th Cir. 1985); Irby v. Sullivan, 737

F.2d 1419, 1423 (5th Cir. 1984); Walker v.

Ford Motor Co., 684 F.2d 1355, 1363-64

(11th Cir. 1982), and cases cited therein.

4a

the amount of damages awarded is per se

unreasonable. (Reply br. at 2, 5; 54

U.S.L.W. 3143-44). However, in a Title

VII case a rule restricting the award of

attorney's fees solely because the dollar

amount of damages is low could result in

less than full relief for identified

individual victims of discrimination who

successfully bring suit. It would also

discourage private attorneys from taking

Title VII cases which involve only

individual claims. These results are

contrary to Congress's intent that

aggrieved individuals, serving as "private

attorney [s] general," complement the

Commission's enforcement efforts. See

Christ iansburg Garment Co. v. Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission, 434

U.S. 412, 416-17 (1978), quoting, Newman

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400,

5a

402 ( 1968). They are also inconsistent

with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission's recently stated policy that

nothing less than "prompt, comprehensive

and complete relief for all individuals

directly affected by [employment discri

mination]" is satisfactory. (See EEOC

Statement on Remedies and Relief For

Individual Cases of Unlawful Discrimi

nation, Feb. 5, 1985, copy attached).

Accordingly, we believe that it is

important that our views be presented to

the Court.

6a

Background

This suit arose from the violent

breakup of a party at the home of Santos

and Jennie Rivera by members of the police

4force of Riverside, California. The

Riveras and their guests, who were all of

Mexican descent, claimed that the warrant

less break-in of their house, accompanied

by massive amounts of tear gas, verbal

abuse and, in some instances, severe

physical abuse, violated their First,

Fourth, Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment

3

We base our statement on the opinions

attached to the petition for certiorari,

the complaint, and the pretrial order

filed in district court. We have not

reviewed the rest of the record in this

case.

Five persons, all plaintiffs herein, were

arrested. Charges against one, Santos

Rivera, were dropped by the police

department prior to the filing of a

complaint. Charges against the other four

were dismissed by the municipal court upon

an explicit finding of no probable cause.

7a

rights, as well as their rights under the

Civil Rights Act of 1870, 42 U.S.C. 1981,

1983, 1986.

Plaintiffs initially named thirty

members of the Riverside police department

as defendants, as well as the chief of

police and the city itself. At an early

stage of the proceedings, summary judgment

as to seventeen of the police officers was

granted on the ground that they merely had

been present at the arrest scene and were

not personally responsible for the

constitutional and other deprivations.

(Pet. App. 8-1).

The litigation continued for a period

of five years, culminating in a favorable

jury award for all eight plaintiffs

against six of the individually named

remaining defendants and the City of

Riverside. Total monetary damages awarded

8a

equalled $33,350.5 (Pet. App. 6-1). The

liability determinations have never been

contested by the city or any other

defendant.

The district court entered an award

of $245,456.25 as attorney's fees and

costs for the preceding five years of

litigation. (Pet. App. 6-1). The court

awarded plaintiffs' attorneys essentially

all the hours requested, disallowing

certain costs as impermissible under

$1988. The court based its decision on

5 Although plaintiffs initially requested

injunctive and declaratory relief, those

requests were not pursued at trial. As

explained by respondents Rivera et al. in

their opposition to the petition for

certiorari, injunctive relief was not

requested as an injunction ordering the

police to obey the law was superfluous.

(Resp. Opp. at 3 n. 3). The district

court, however, indicated that had such an

"obey the law" injunction been sought, it

would have been granted based on the

severity of the constitutional violations

by some of the officers. (See Opp. Cert.

App. A-1 - A-2).

9a

findings that, inter alia, the "action

presented complex issues of law in a case

involving eight individual plaintiffs,

eleven individual defendants and a

municipal defendant" (Pet. App. 6-2);

" [g]iven the nature of this lawsuit, many

attorneys . . . would have been reluctant

to institute this action" (Ibid.); and

"[p]laintiffs maintained this civil action

in order to secure the vindication of

important constitutional rights." (Id. at

6-5 ) .

The court of appeals upheld the

award. (Pet. App. 5-1). It refused to

reduce the award because of the unnecess-

ful[sic] claims, concluding that they were

related to the successful claims. (Id. at

5-9 ). The court also rejected defendants'

10a

contention that the amount of attorney's

fees award must be proportionate to the

jury verdict. (Id. at 5-11 - 5-13).

Thereafter, a petition for writ of

certiorari was granted, and the fees

judgment was vacated and remanded for

further proceedings in light of Hensley v.

Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 ( 1983). (Pet.

APP* 4-1).

After a subsequent hearing and

briefing, and after reconsidering the

record, the district court affirmed the

original fee award. (Pet. App. 2-1). The

court found that the relatively small size

of the damage award resulted from "(a) the

general reluctance of jurors to make large

awards against police officers, and (b)

11a

the dignified restraint which the plain

tiffs exercised in describing their

ginjuries to the jury." (Id. at 2-5).

The court refused to reduce the award

because of the unsuccessful claims,

finding that plaintiffs were successful on

the "central and most important

issue . . . [of] whether there was police

misconduct;" "all claims . . . were based

on a common core of facts;" and "[t]he

At the hearing, the district court

elaborated on this point, stating:

I have tried several civil rights

violation cases in which police

officers have figured and in the main

they prevailed because juries do not

bring in verdicts against police

officers very readily nor against

cities. The size of the verdicts

against the individuals is not at all

surprising because juries are very

reluctant to bring in large verdicts

against police officers who don't

have the resources to answer those

verdicts. The relief here I think

was absolutely complete. (Resp. App.

B-5).

12a

claims on which plaintiffs did not prevail

were closely related to the claims on

which they did prevail" and "cannot

reasonably be separated. . . ." (Id. at

72-6). The court found that the amount of

time expended by counsel "reflected sound

legal judgment" and was reasonable because

" [c]ounsel for plaintiffs achieved

excellent results . . . ." (Id. at 2-7

-2-8). The district court stated that it

was

shocked at some of the acts of the

police officers in this case and was

convinced from the testimony that

these acts were motivated by a

general hostility to the Chicanos

community in the area where the

incident occurred. The amount of

time expended by plaintiffs' counsel

in conducting this litigation was

clearly reasonable and necessary to

The court noted that given the conflicting

testimony about the roles of individual

police officers, "[ujnder the circum

stances of this case, it was reasonable

for plaintiffs initially to name thirty-

one individual defendants." (Pet. App. 2-4).

14a

of that success and the amount of the

award." (Id. at 1-7). The court of

appeals again rejected "the proposition

that there need be a relationship between

the amount of damages . . . and the amount

of attorney's fees . . . ." (Id. at 1-8

-1-9).

On August 9, 1985, defendants filed a

petition for a writ of certiorari,

presenting the question "[w]hat are the

proper standards within which a district

court may exercise its discretion in

awarding attorney's fees to prevailing

parties under Section 1988 . . . ."

Petitioners contended generally that the

district court abused its discretion and

disregarded Hensley by failing to reduce

the fee award. (Pet. 29-37). Petitioners

challenged a number of specific aspects of

the fee award, primarily the court's

13a

serve the public interest as well as

the interests of plaintiffs in the

vindication of their constitutional

rights.

(Id. at 2-8 - 2-9).

The court of appeals affirmed,

finding that the district court had

correctly reconsidered the case in light

of Hensley and that the fee award was

within the district court's discretion.

(Pet. App. 1-4). The court held that the

record supports the district court's

findings that all the claims involved

common facts and related legal theories.

(Id. at 1-6). According to the court of

appeals, the district court followed

Hensley's precepts by focusing on "the

degree of success in relation to the

ultimate award of fees and [finding] a

reasonable relationship between the extent

15a

failure to reduce the hours allotted for

seven items. (Pet. 40-46). Petitioners

also argued that counsel for plaintiffs'

time records were inadequate. (Pet.

49-58).8

On August 28, 1985, Justice Rehnquist

issued his opinion on the stay applica

tion, discussing solely the "significant

question [presented in this case] invol

ving the construction of §1988: should a

court, in determining the amount of

'reasonable attorney's fee' under the

statute, consider the amount of monetary

damages. . . . " 54 U.S.L.W. at 3143.9 In

Q The petition only obliquely refers to the

district court's decision not to reduce

the fees to account for unsuccessful

claims. See, e,q. , Pet. at 35, 54.

9 Justice Rehnauist noted that the issue

framed by petitioners "is not a model of

specificity, [but] it does 'fairly

subsume,' inter alia, the dispropor-

tionality issue." 54 U.S.L.W. at 3143.

16a

his view, "the award of attorney's fees in

this case, representing more than seven

times the amount of the monetary judgment

obtained, is so disproportionately large

that it could hardly be described as

'reasonable.' "Id. at 3144. After noting

a split in the circuits on the issue,10

Justice Rehnquist found that "[njeither

Hens 1ey nor Blum . . . addressed whether

disproportionately between the amount of

the monetary judgment obtained and the

Justice Rehnquist contrasted DiFilippo v.

Morizio, 759 F.2d 231 (2d Cir. 1985) , and

Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546 (10th Cir.

19S3), which held that the size of the

award alone does not warrant reduction of

a fee, with Bonner v. Coughlin, 657 F.2d

931 (7th Cir. 19^1), which held that the

amount of the recovery may indicate the

reasonableness of the time spent. 54

U.S.L.W. 3144. He failed to cite a later

Seventh Circuit decision, Lynch v. City of

Milwaukee, 747 F.2d 423 (7t¥ cir. 1984),

wh i ch Held that an award of nominal

damages does not warrant reduction of the

fee award where the plaintiff primarily

sought nonmonetary relief.

17a

amount of the attorney's fee, standing

alone, is a consideration that might

properly lead a court to reduce the fee."

Ibid. (emphasis added). He concluded

that, except in cases involving primarily

injunctive relief or defendants' bad faith

conduct, "the time billed for a lawsuit

must bear a reasonable relationship not

only to the difficulty of the issues

involved but to the amount to be gained or

lost by the client in the event of success

or failure." Ibid. Justice Rehnquist

held that the probability of petitioners'

success on this issue was sufficiently

great to warrant a stay.

After the issuance of Justice

Rehnquist's opinion, the disproportionali-

ty issue was briefed by respondents in

their opposition to the petition and was

the focus of petitioners' reply brief.

18a

Discussion11

It is our position that the size of

the damage award, standing alone, does not

justify reduction of the attorney's fees

award for counsel time otherwise reason

ably expended on successful claims. This

is not to say, however, that the amount of

monetary relief is irrelevant. The

Supreme Court held in Hensley v.

Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424, 436 ( 1983), that

"the most critical factor [in setting a

fee award] is the degree of success

We will discuss the legal issue of whether

an award of attorney's fees must be in

proportion to the monetary relief awarded.

The petition also raises numerous factual

issues regarding the reasonableness of the

hours expended by plaintiffs' counsel. We

take no position on these issues, the

resolution of which depends on a review of

the full record. However, in our view,

the factual issues articulated by peti

tioners are not sufficiently significant

to warrant briefing by the government,

particularly inasmuch as the standard of

review is abuse of discretion.

19a

obtained." The amount of relief awarded

is one consideration in determining

plaintiff's level of success. However,

the damage award can not be viewed in a

vacuum or in absolute terms, as peti

tioners contend. See reply br. at 5.

Rather, to measure success the amount of

monetary relief awarded should be compared

to the relief which is sought or could be

reasonably expected if plaintiff were

fully successful. This approach is

consistent with the intent and purpose of

the fee-shifting statute, the standards

adopted in Hensley, and the near uniform

view of the courts of appeals. Because

the district court basically followed this

approach, we recommend supporting respon

dents on this legal issue.

20a

1. In the context of Title VII, the

Supreme Court recognized in Christiansburg

Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412, 418

(1978), that individual plaintiffs are the

"chosen instrument[s] of Congress to

vindicate 'a policy that Congress con

sidered of the highest priority.'"

Quoting, Newman v. Piggie Park Enter

prises, 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968). There

are "strong equitable considerations" for

granting plaintiffs fees, particularly

because they are being "award[ed]. . .

against a violator of federal law." 434

U.S. at 418. Thus, the legislative

history of Title VII demonstrates that

"one of Congress's primary purposes in

enacting the section [providing attorney's

fees to a prevailing party] was to 'make

it easier for a plaintiff of limited means

to bring a meritorious suit.'" 434 U.S

21a

at 420, quoting, 110 Cong. Rec. 12724

(1964) (remarks of Sen. Humphrey). Accord,

New York Gaslight Club v. Carey, 447 U.S.

54, 63 (1980). The same policies underlie

the Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards

Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. 1988. The Senate

report found that "fees are an integral

part of the remedy necessary to achieve

compliance with our statutory policies."

S. Rep. No. 94-1011 (1976) ("Senate

Report") at 3. See also, e.g., Senate

Report at 2 (enforcement of civil rights

laws "depend [s] heavily upon private

enforcement and fee awards have proved an

essential remedy if private citizens are

to have a meaningful opportunity to

vindicate . . . important Congressional

policies"); H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558 (1976)

at 1 ("House Report") ("effective enforce

22a

ment of Federal civil rights depends

largely on the efforts of private citi

zens" ).

The standard suggested by Justice

Rehnguist — that attorney's hours

otherwise reasonable and necessary to the

litigation should not be fully compensated

if their value exceeds the amount of

damages recovered — will necessarily

cause attorneys to pursue less vigorously

claims of low monetary value, such as

those involving single individuals. This

would defeat the purpose of the fee-shif

ting statutes to encourage full enforce

ment of civil rights laws. It would also

frustrate Congress's intent to award fees

"adequate to attract competent counsel,

but which do not produce windfalls"

(Senate Report at 6), inasmuch as compe

23a

tent attorneys will have less incentive to

represent individual claimants who cannot

finance their own litigation.

The legislative history of §1988 and

other fee provisions demonstrate that the

level of monetary recovery should not, of

itself, dictate the amount of attorney's

fees. For example, the Senate Report

states: "It is intended that the amount

of fees awarded . . . be governed by the

same standards which prevail in other

types of equally complex Federal liti

gation . . . and not be reduced because

the rights involved may be nonpecuniary in

nature." Senate Report at 6 (emphasis

added). See also 122 Cong. Rec. 31832

(September 22, 1976) (Remarks of Sen.

Hathaway in support of bill which became

§1988) ("In the typical case . . . the

citizen who must enforce the [civil

24a

rights] provisions through the courts has

little or no money with which to hire a

lawyer, and there is often no damage claim

from which an attorney could draw his

fee.") Similarly, the House Report

recognized that not all civil rights

litigation results in large damage awards,

and that "in some cases immunity doctrines

and special defenses . . . preclude or

severely limit the damage remedy. Conse

quently, awarding counsel fees to pre

vailing plaintiffs in such litigation is

particularly important and necessary if

Federal civil and constitutional rights

are to be adequately protected." House

Report at 9.12

7*2 ■The legislative history's citation to

three early attorney's fees cases is

significant. In the Senate Report (at 6),

Congress cited approvingly use of the

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488

F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 19 74) , factors and gave

as examples of their correct application

three cases: Stanford Daily v. Zurcher,

25a

2. Reduction of a fee award based

solely on the amount of damages recovered

is also inconsistent with the standards

for assessing fees previously established

by the Supreme Court. In Hensley v.

Eckerhart, the Court clarified the means

by which "adequate" fees are to be

determined: initially, the "number of

hours reasonably expended on the litiga

tion [is] multiplied by a reasonable

hourly rate." 461 U.S. at 433. This

figure, sometimes called the "lodestar"

(e.g. Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880,

890-91 (D.C. cir. 1980) (en banc)), is

then subject to further adjustment based,

64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Ca. 1974); Davis v.

County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.dT 1f9444

(C.D. Ca. 1974); and Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of E<j., 66 F.R.D. 683

(W.D.N.C. 1975). In none of those cases

were large amounts of monetary damages

awarded, if any, and, in the Stanford

Daily case, no injunctive relief was

ordered either.

26a

among other things, on the "'results

obtained.'" 461 U.S. at 434, quoting,

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.,

488 F . 2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974). However,

the Court made it clear that "[wjhere a

plaintiff has obtained excellent results,

his attorney should recover a fully

compensatory fee. Normally this will

encompass all hours reasonably expended on

the litigation . . ." 461 U.S. at 435.

This holding forecloses any argument that

a fully successful plaintiff should be

awarded less than a fully compensatory fee

solely because the amount of damages at

issue was low.

Furthermore, as noted above, the

Court directed that in setting fees the

primary consideration should be on whether

the "degree of success" justified the

hours expended on the litigation. There

27a

can be no question that where a signifi

cant aspect of the relief sought is

monetary, the amount of the damages is

relevant in measuring the degree of

success. However, the Court's repeated

use of terms such as "degree of success"

(461 U.S. at 436 ), "extent of success"

(id. at 438, 439 n. 14), and "level of

success" (id. at 434, 439), indicate that

the important comparison is between the

relief sought and the relief obtained.

The Court in Hensley specifically

rejected a "precise rule or formula" or a

"mathematical approach" to determine

attorneys' fees by comparing the number of

successful claims to the total number of

claims asserted. 461 U.S. at 436, 435 n.

11. As the Court remarked: "Such a ratio

provides little aid in determining what is

a reasonable fee in light of all relevant

28a

factors." 461 U.S. at 435-36 n. 11. The

Court also rejected a strict mathematical

approach in Blum v. Stenson, ____ U.S.

___, 104 S.Ct. 1541, 1549-50 n. 16 ( 1984),

holding that the numbers of persons

benefitted is not a valid consideration in

setting fees. The Court commented,

"presumably, counsel will spend as much

time and will be as diligent in litigating

a case that benefits a small class of

people, or indeed, in protecting the civil

rights of a single individual." Ibid. For

the same reason — that counsel's dili

gence will not vary according to the

amount involved — a mathematical formula

requiring that the fee award be in

proportion to the damages is improper.

Justice Rehnquist suggests that any

attorney using "billing judgment" would

not bill more than the amount recovered.

29a

5 4 ttyS.L.W. at 3144. | However,^ as the

above cited legislative history Reflects,

the purpose of the civil rights fee-shif-

. . .. pting provisions is to allow individuals to

obtain redress for infringement of rights

which cannot be valued in strict monetary

i 3terms. See Jaguette v. Black Hawk

County, Iowa, 710 F.2d 455, 460 (8th Cir.

Justice Rehnquist would not apply a

mathematical formula to cases involving

primarily injunctive or other nonpecuniary

relief. 54 U.S.L.W. at 3144. However,

the same rights are involved, and in some

Title VII cases this distinction makes

little sense. For example, two indivi

duals may have identical claims alleging

discrimination in their employer's failure

to promote them to jobs paying $4,000 more

per year. One obtains $10,000 in back pay

and«&n injunction ordering his promotion.

The other obtains $10,000 in back pay but

does not seek an injunction because before

trial he found a higher paying job. If

each incurred $15,000 in attorney's fees

on the liability issue, there is no

logical basis for concluding that the

amount of fees is reasonable in one case

because an injunction was obtained, but it

is per se unreasonable in the other case

because it is disproportionate to the

amount of recovery.

30a

1983 ) ("marketplace factors are often

absent from civil rights litigation,"

because "it is difficult to place a

pecuniary value on relief sought when the

injury involves the infringement of the

civil or constitutional rights of a

plaintiff"). Furthermore, the "billing

judgment" required of counsel is to

"exclude from a fee request hours that are

excessive, redundant, or otherwise

unnecessary . . . Hensley, 461 U.S. at

434. We find no support in Hensley or any

other authority for excluding under the

rubric of "billing judgment" compensation

for necessary hours expended on a suc-

14cessful civil rights claim.

T4- The determination that the number of hours

is "reasonable" necessarily includes a

finding that there was a valid reason for

the hours expended. For example, in an

individual Title VII case, substantial

attorney time may be required because of

the complexity of the legal issues or

because of defendant's tactics. If there

31a

3. A look at the pertinent recent

court of appeals' decisions reveal near

uniform agreement that the size of the

damage award is one relevant factor in

assessing the amount of fees, but that

there is no necessary proportional

relationship between the amount of damages

the amount of fees awarded. See Nephew v.

City of Aurora, 766 F.2d 1464, 1467 (10th

Cir. 1985); DiFilippo v, Morizio, 759 F.2d

231, 235-36 (2d Cir. 1985); Lynch v. City

of Milwaukee, 747 F.2d 423, 428-29 & n. 5

(7th Cir. 1984); Wojtkowski v. Cade, 725

F.2d 127, 131 (1st Cir. 1984); Jaguette v.

Black Hawk County, Iowa, 710 F.2d 455,

458, 461 (8th Cir. 1983); Perez v.

is no valid explanation for the amount of

work, it is not reasonable. In this case,

the district court found that the hours

were reasonably expended in view of the

complexity of the case. (Pet. App. 2-2).

Petitioner's real quarrel is with this

determination, as their petition reflects.

32a

University of Puerto Rico, 600 F.2d 1, 2

(1st Cir. 1979); Burt v. Abel, 585 F.2d

613, 618 (4th Cir. 1978); See also Bonner

v. Coughlin, 657 F.2d 931, 934 (7th Cir.

1981).15

Justice Rehnquist cites two cases

— DiFilippo v. Morizio and Ramos v. Lamm,

71*3 F ."2c! 546 ( 10th Cir. 1$fT“ - for the

proposition that courts of appeals have

held that the amount of damages received

is not a permissible factor in awarding

attorney's fees. DiFilippo, however,

holds that comparison of damages to

"typical . . . awards in the same type of

case" is relevant. 759 F.2d at 236. While

Ramos does state that fees should not be

reduced because the recovery is small, the

Tenth Circuit subsequently distinguished

Ramos on the ground that only declaratory

and injunctive relief had been requested.

Nephew v. City of Aurora, 766 F.2d at 1465-66.

In Cunningham v. City of McKeesport,

753 F. 2d” 262, 268-69 (3rcTcir. 1985), pet.

for cert, filed, 53 U.S.L.W. 3839 (May 14,

1985), also cited by Justice Rehnquist,

the court of appeals held that it was

incorrect for the district court to reduce

the attorney's fee award by 50% on grounds

not raised by defendants. The issue

regarding the proportion of fees sought

($35,000) to damages awarded ($17,000) was

discussed chiefly in a statement by Judge

Adams dissenting from the denial of

33a

Courts which have analyzed the issue

in detail after Hensley have recognized

that the amount of damages is appropriate

ly considered as one measure of the level

of success. See Nephew v. City of Aurora,

766 F.2d at 1466-67; DiFilippo v. Morizio,

759 F.2d at 231; Jaguette v. Black Hawk

County, Iowa, 710 F.2d at 461. The

relevant comparison is "whether the size

of the award is commensurate with awards

in [similar] cases generally, rather than

whether the award viewed in some absolute

terms is high or low." DiFilippo, 759

F .2d at 235. Another possible comparison

is between the "remedy sought . . . and

remedy obtained . . . ." Jaguette, 710

F.2d at 461. Where the comparison reveals

that "plaintiffs won an unambiguous

rehearing en banc

34a

victory . . . their attorneys should

recover a fully compensatory fee."

DiFilippo, 759 F.2d at 235.

4. The district court in this case

correctly considered the size of the

damage award in relation to the relief

reasonably to be expected in this kind of

case. The court found that the size of

the award did not reflect limited success,

but rather it resulted from a jury's

general reluctance to make large awards

against police officers and respondents'

refusal to "play up" their "insulting and

humiliating" injuries. (Pet. App. 2-5

-2-6). The court pointed out at the

hearing that respondents were much more

successful than the plaintiffs in several

other civil rights cases, with which the

court was familiar, involving police

officers and cities. (Resp. App. B-5).

35a

Accordingly, the court found that respon

dents had achieved "excellent results."

(Pet. 2-7).

The district court can be criticized

for not making more detailed findings and

for relying solely on its own experience

in determining that the results were

better than those generally obtained in

the same kind of case. Nevertheless, the

court appropriately considered the size of

the damage award as one relevant factor in

determining the extent of success, and

petitioners have pointed to nothing which

indicates that the court's findings

regarding the damage award were erroneous.

Accordingly, we recommend that a

brief be filed in favor of respondents

discussing the legal standards to be

36a

applied to requests for attorney's fees

greater than the amount of the monetary

judgment.

Hamilton Graphics, Inc.— 200 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y.— (212) 966-4177