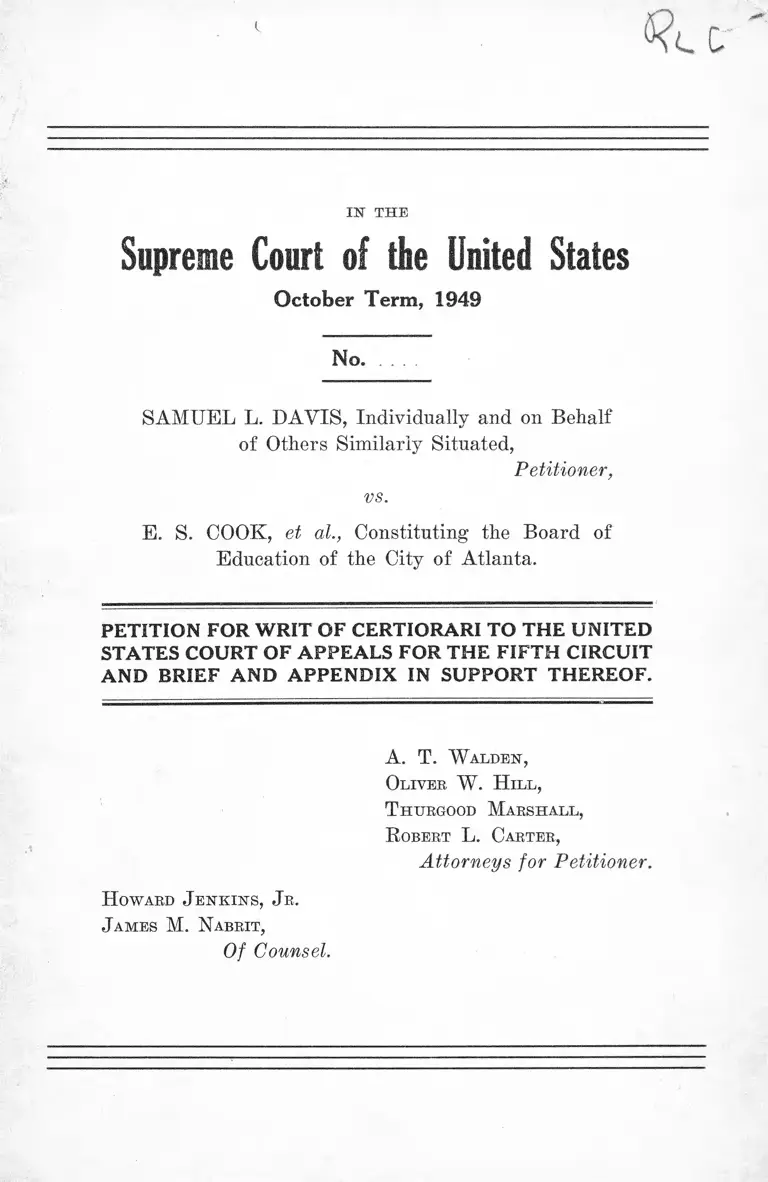

Davis v. Cook Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and Brief and Appendix in Support Thereof

Public Court Documents

May 5, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Cook Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and Brief and Appendix in Support Thereof, 1950. b3fddc5e-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/33d7a828-fbee-41b4-8d89-24f644dcea69/davis-v-cook-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit-and-brief-and-appendix-in-support-thereof. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IK THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949

No. .

SAMUEL L. DAVIS, Individually and on Behalf

of Others Similarly Situated,

Petitioner,

vs.

E. S. COOK, et at., Constituting the Board of

Education of the City of Atlanta.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

AND BRIEF AND APPENDIX IN SUPPORT THEREOF.

A. T. W alden,

Oliver W . H ill,

T hurgood Marshall,

R obert L. Carter,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

H oward J enkins, J r .

J ames M. Nabrit,

Of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

P etition for W rit of Certiorari:

Summary Statement of the Matter Involved ---------- 2

Statement of Facts _____________________________ 4

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals -------------------- 12

Jurisdiction ______________________ 13

Question Presented ______________________________ 14

Reasons Relied Upon for Allowance of the W rit__ 14

Conclusion_______________________________________ 19

Brief in Support T hereof:

Opinions of the Courts Below____________________ 21

Jurisdiction______________________________________ 21

Statement of the Case ___________________________ 22

Errors Relied U pon_____________________________ 22

A rgument :

I. Administrative remedies need not be pursued

prior to resort to federal courts unless manda

tory in nature_______________________________ 23

11

PAGE

II. The nature of petitioner’s cause is such as to

require dispensing with the pursuit of admin

istrative remedies and immediate judicial de

termination —

III. The State Board of Education is without statu

tory jurisdiction or authority to grant petitioner

the relief he seeks------ --------------------------------

IV. The procedure provided for appeal to the Atlanta

Board of Education is in the nature of a peti

tion for rehearing or reconsideration by the

Board and, hence, need not be exhausted prior

to resort to the federal courts-------------------------

V. The procedure provided for appeal to the

Atlanta Board of Education fails to satisfy

the minimum requirements of due process of

law--------------- --------- ------------------------------------ 32

VI. The opinion of the Court of Appeals in this case

is in apparent conflict with the Court of Appeals

of the Ninth Circuit-------------------------------------

40

Conclusion

Appendix —

I l l

Table of Cases

PAGE

Aircraft & Diesel Equipment Corp. y. Hirseh, 331 U. S.

752 ___________ ..___________ __- _ — — 17, 26

Alston v. School Board, 112 P. 2d 992 (C. C. A. 4th

1940); cert. den. 311 IT. S. 693 __________ _______ 25

Boney v. County Board of Education, 45 S. E. 2d 442

(1947) _____________________ ___________________ 30

Bryant v. Board of Education, 156 Ga. 688, 119 S. E.

601 (1923) ________________________ —_______..-16, 23

Carter v. Johnson, 186 Ga. 167, 197 S. E. 258

(1938) _____________________________________15,28,37

Colyer v. Skeffington, 265 Fed. 17 (D. Mass. 1920) ___ 18, 36

County Board of Education v. Young, 187 Ga. 664, 1

S. E. 2d 739 (1939) ____________ _________16,23,24,25

Downer v. Stevens, 22 S. E. 2d 139 (1942) ....—.15,25,29

Fordham v. Harrell, 197 Ga. 135, 28 S. E. 2d 463

(1943) ___________________________ _—15,25,28,30,37

Kansas City So. By. Co. v. Ogden Levee Dist., 15 F. 2d

637 (C. C. A. 8th 1926) ____ ____________ ________ 18,36

Levers v. Anderson, 326 IT. S. 219 ______ ________ 15, 31

Londoner v. Denver, 210 IT. S. 373 __________________ 35

Moore v. Illinois Central Railway Co., 312 IT. S. 630__ 16, 24

Morgan v. United States, 304 U. S. 1 ______________ 18, 35

Munn v. Des Moines National Bank, 18 F. 2d 269

(C. C. A. 8th 1927) _________________________ 17,18,34

Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public Utilities Commission,

301 U. S. 292 __________________________________18, 36

Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Bussell, 261 U. S. 290__ 17, 25

IV

Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Kuykendall, 265

PAGE

U. S. 196 ______________________________________17, 36

Porter v. Investors Syndicate, 286 U. S. 461------------17, 36

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ------------------------------- 38

Steele v. Louisville & N. B. Co., 323 U. S. 192---------- 15, 36

Trans-Pacific Airlines v. Hawaiian Airlines, 174 F. 2d

63 (C. C. A. 9th 1949)------------ ---------------------------- 16, 38

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen &

Enginemen, 323 IT. S. 210----------------------------------15, 36

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U. S.

444 ____________________________________________ 38

United States v. Morgan, 298 U. S. 468 --------------------18, 35

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 -------------------------- 25

V

Constitutional and Statutory Authorities

Constitution of the State op Georgia o f 1945

PAGE

A rticle VIII

Section II, Chap. 2-65, § 2-6501 _________________ 40

Section III, Chap. 2-66, § 2-6601 ________________ 41

Section VII, Chap. 2-70, § 2-7001 _______________ 5,42

Section VIII, Chap. 2-71, § 2-7101 ______________ 42

Section XI, Chap. 2-74, § 7401, § 7402 __________42,43

Georgia Code A nnotated

Section 32-401 (Acts 1937, p. 864; Acts 1943, pp.

636, 638) ______________________ ____________ 43

Section 32-402 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 865; Acts 1943,

pp. 636, 637, 638) ___________________________ _ 43

Section 32-403 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 865; Acts 1943

pp. 636, 638) ________________________________ _ 44

Section 32-404 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 865) _________ 44

Section 32-405 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 865) ________44, 45

Section 32-406 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 865) ________ 45

Section 32-407 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 866) ________ 45

Section 32-408 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 866) ________45, 46

Section 32-409 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 866) _____...___ 4q

Section 32-410 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 866) ________ 46

Section 32-411 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 866) ________ 46

Section 32-411.1 (Acts 1947, pp. 668, 669) ______46,47

Section 32-412 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 867) ________ 47

Section 32-414 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 867) _______ 30,47

Section 32-504 (Acts 1937, pp. 864, 867) ________ 47

V I

Section 32-601 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883) ---------5, 27, 48

Section 32-602 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883) ---------5,14,48

Section 32-603 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883) -------------- 48

Section 32-604 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883) ---------- -27, 48

Section 32-605 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883) --------------5,15,

30, 37, 48

Section 32-606 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883) -------------- 49

Section 32-608 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 884) ------------ 27,49

Section 32-609 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 884; Acts 1947, ̂

pp. 668, 669) ---------------------------------------5,14, 2/,o0

Section 32-610 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 885) ---------5,27,51

Section 32-611 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 886) ------------ 27,51

Section 32-612 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 886) ------------51, 52

Section 32-613 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 886) — 6,14, 27, 52

Section 32-614 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 886) — 6, 28, 52, 53

Section 32-615 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 887; Acts 1946,

pp. 201, 216; Acts 1947, pp. 668, 670) — 6,14, 28, 53

Section 32-616 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883) — 6,14, 28, 54

Section 32-622 (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 890) -------------- 54

Section 32-910 (Acts 1919, p. 324; Acts 1947, pp.

1189, 1190) __________________________ 14,23,30,54

Section 32-1010 (Acts 1919, p. 352; Acts 1947, pp.

1189, 1191) ______________________________15,30,55

Section 32-1111 (Acts 1919, p. 340; Acts 1946, pp.

206, 211) ___________________________________29>55

PAGE

11ST T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme of the

United States:

Petitioner respectfully prays that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, reversing the judgment of

the District Court of the United States for the Northern

District of Georgia which had entered judgment, enjoining

and restraining the respondents from paying petitioner and

other Negro teachers and principals in the public schools of

Atlanta less salary than is paid white teachers and prin

cipals of equal qualifications and experience, and perform

ing substantially the same duties, solely on account of race

and color, in violation of the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

October Term, 1949

No. ____

Samuel L. D avis, Individually and on

Behalf of Others Similarly Situated,

Petitioner,

E. S. Cook, et al., Constituting the Board

of Education of the City of Atlanta.

vs.

2

Summary Statement of the Matter Involved.

This ease has a long history. Until some time in 1942,

teachers and principals in the Atlanta public schools were

paid pursuant to a dual salary schedule—one for Negro

teachers and principals and one for white teachers and prin

cipals. These schedules admittedly discriminated against

Negro teachers and principals (R. 36, 42).

On January 30, 1941, a petition, on behalf of a teachers’

association representing all Negro teachers employed in the

Atlanta public school system, was filed with the Atlanta

Board of Education alleging discrimination in the payment

of salaries, and requesting that Negro teachers and prin

cipals be paid the same salary as other teachers of equal

qualifications and experience and performing substantially

the same duties, without regard to race and color (R. 10).

On November 26, 1941, a second petition of the same nature

was filed, but respondents took no action (R. 10).

On February 17, 1942, William Reeves, a Negro teacher

employed in the school system, brought suit in the United

States District Court against the respondents seeking to

enjoin the practice, custom and usage of paying Negro

teachers and principals less salary than is paid white teach

ers and principals. After the filing of the Reeves ’ suit, re

spondents announced that they were abolishing the dual

schedule of salaries and ordered the institution of a new

single salary schedule which would be free of discrimina

tion on account of race and color (R. 42, 43). (The Board’s

resolution authorizing this action is set out on page 43 of the

Record.)

On July 2,1943, the instant complaint of the present peti

tioner was filed in the United States District Court (R. 2-

14). On July 20, 1943, a motion to dismiss was filed (R. 14-

17). No allegation was there made that petitioner had

3

failed to exhaust any state administrative remedies. On

June 29, 1944, the motion was overruled (R. 17-30). On

July 8, 1944, the answer was filed (R. 30-38). Here, again,

respondents did not allege as a defense to this action failure

on petitioner’s part to exhaust administrative remedies.

The trial on the merits did not take place until November,

1947, three years later. Additional argument was heard in

July, 1948 (R. 53), and on September 28, 1948, the trial

court issued findings of fact and conclusions of law (R. JO-

64). It found that the wide differential between the salaries

of Negro and white teachers could only be the result of the

discrimination based upon race and color in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment (R. 61). It further found that the

State Board of Education fixed the state’s contribution to

the educational fund of Atlanta (R. 42). That on the salary

schedule which the State Board prescribes the minimum

rate of pay for Negro teachers is less than the minimum

rate of pay prescribed for white teachers (R. 42). That

the funds contributed by the State Board do not fix the rate

of pay of the teachers, since the Atlanta Board provides

additional funds secured through local taxation which deter

mine the salary of teachers in the system (R. 42). The

trial court’s findings of fact and conclusions of law are re

ported in 80 F. Supp. 443.

On December 16, 1948, the final judgment and decree of

the court was issued in which the court enjoined and re

strained the respondents from discriminating in the pay

ment of salaries against petitioner and other Negro teachers

in the public school system and gave the Atlanta Board of

Education until September 1, 1949, to readjust their salary

schedules in accordance with the decree (R. 64, 65).

Notice of appeal was filed on December 30,1948 (R. 66).

The appeal was argued before the United States Court of

4

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on October 17, 1949 (R. 69),

and that court reversed and remanded the judgment of the

lower court on December 28,1949 (R. 86). The main ground

of reversal was that the petitioner had failed to exhaust

administrative remedies (R. 80-85). It was, therefore,

ordered that the cause be remanded to the District Court

to remain there pending for a reasonable time to permit-

petitioner to avail himself of the administrative remedies

which the court felt must be pursued before the cause was

ripe for the intervention of the federal courts (R. 86). A

motion to extend the time for filing the petition for rehear

ing was granted on January 11, 1950 (R. 88). Petition for

rehearing was filed on January 27, 1950 (R. 89-94), and was

denied on February 6, 1950 (R. 95). Whereupon, petitioner

brings the cause here by this petition for writ of certiorari.

Statement of Facts.

This suit was begun by petitioner in the United States

District Court on July 2, 1943, almost seven years ago. It

is to be remembered, however, that the efforts of petitioner

and the class he represents—Negro teachers and principals

in the Atlanta public school system—to have the discrimi

nation in the payment of salaries on the basis of race and

color removed, date back to the filing of the petition with the

Atlanta Board on January 30,1941, over nine years ago (R.

10, par. 15). A second petition was filed on November 26,

1941, and a suit by a William Reeves was commenced in

1942 because of the failure of the respondents to remove

the discrimination in the payment of salaries (R. 43, 72).

The findings of fact of the District Court, beginning at

page 40 of the record and reported in 80 F. Supp. 443, are

adopted and accepted by the petitioner as a correct state

ment of the facts of the case, and these findings were not

disputed by the Court of Appeals.

5

Petitioner is a Negro teacher employed by the Atlanta

Board of Education. He brings this action as a class suit,

pursuant to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

as the representative of all the Negro teachers and prin

cipals employed by the Atlanta Board of Education. He

alleges that the Atlanta Board is paying to him, and to all

other Negro teachers employed in the school system, a

salary less than is being paid to white teachers and prin

cipals with equal qualifications and experience solely on the

basis of race and color (R. 9, 40, 41).

The City of Atlanta, pursuant to Article VIII, Chapter

2-70, Section 2-7001 of the Constitution of the State of

Georgia of 19451 is permitted to maintain and support an

independent school system. All teachers and principals are

employed by the Atlanta Board of Education on the recom

mendation of its Superintendent of Schools, all respondents

in this action (§32-605, Ga. Code Ann., Acts 1937, pp. 882,

883).

Pursuant to the public policy of the state to provide equal

educational advantages to all children of public school age

(§ 32-601, Ga. Code Ann., Act 1937, pp. 882,883), the state has

established certain uniform minimum standards with regard

to the employment and payment of teachers in public schools

throughout the state. All teachers must hold state certifi

cates (§32-610, Ga. Code Ann., Acts 1937, pp. 882, 885). All

public schools must be operated at least seven months per

year (§32-602, Ga. Code Ann., Act 1937, pp. 882, 883). The

State Board is authorized to determine the minimum num

ber of teachers the various school systems may employ for

the minimum seven-month school year (§ 32-609, Ga. Code

Ann., Acts 1937, pp. 882, 884; Acts 1947, pp. 668, 669). The

1 All constitutional and statutory provisions referred to here and

in the supporting brief may be found in the Appendix.

6

State Board is required to fix a schedule of minimum salaries

to be paid to various classes of teachers prescribed by them

out of the public school funds of the state (§32-613, Ga.

Code Ann., Acts 1937, pp. 882, 886). The public school fund

is to be used to pay all teachers “ for not less than seven

months each year in accordance with the salary schedule

prescribed by the Board” (§32-614, Ga. Code Ann., Acts

1937, pp. 882, 886). Prior to the beginning of each school

term, the State Board is required to fix the minimum sched

ule of teachers’ salaries, and the minimum number of teach

ers which each school system must employ for the ensuing

year (§32-616, Ga. Code. Ann., Acts 1937, pp. 882,883). Each

school system is permitted to operate its schools more than

a minimum of seven months, supplement the state’s sched

ule of salaries and employ teachers in addition to those re

quired in Section 32-616, Ga. Code Ann. All teachers em

ployed during the school term must receive at least the

minimum rate of pay prescribed in the state’s schedule

(§32-615, Ga. Code Ann., Acts 1937, pp. 882, 887; Acts 1946,

pp. 206-216; Acts 1947, pp. 668, 670).

The State Board of Education each year establishes a

minimum schedule of salaries payable in the Atlanta school

system (Exhibits 12 and 30). These schedules prescribe

lower minimum rates of pay for Negro teachers than those

prescribed for white teachers (Exhibits 12 and 30). The

state contributes to the Atlanta Board funds sufficient to

pay the minimum number of teachers which the state re

quires it to employ at the minimum rate prescribed in the

schedule of the State Board of Education (Exhibits 12 and

30). All Atlanta teachers receive considerably more than

the minimum prescribed by the state’s salary schedule (Ex

hibits 13, 12 and 30). The Atlanta Board fixes the actual

salaries payable to its teachers pursuant to its own rules

and regulations (Exhibits 13, 14 and B. 42). The funds

7

raised locally and the funds contributed by the state are

commingled into one general fund, out of which the Atlanta

School Board pays the salaries of teachers and principals

in its public schools.

The present salary schedule and scheme, under which

the Atlanta Board is now operating, was not put into effect

until September, 1944, over a year after the institution of

this suit (R. 47). Adoption of the present scheme resulted

in an average increase for the Negro teachers over the old

scale of approximately $8 per month and of slightly under

$2 per month for white teachers (R. 47), and, therefore, as

the Court of Appeals stated in its opinion, the differential

in the minimum rate of pay of Negro and white teachers

which the salary schedule of the State Board of Education

prescribed was eliminated (R. 79).

The new salary scheme of the Atlanta Board of Educa

tion established four separate categories—high school prin

cipals, elementary school principals, junior and senior high

school teachers and elementary school teachers (R. 45, 46).

In each category there are three to four Tracks, and on

each Track there are sixteen to nineteen steps (R. 45, 46).

As the trial court found, initial placement on the Track is

of vital importance because this determines the number of

years required to attain the “ maximum placement where

his salary is frozen unless in exercise of official discretion

based upon subjective qualifications, he is placed on another

track” (R. 48). Thus, the ultimate salary of a high school

principal placed upon Track I is $250 per month, while his

ultimate salary if placed on Track IV is $375 per month

(R. 45). Similarly, an elementary school principal who is

placed on Track I, Step 12 receives a salary of $215 per

month, and it will take him eight years to obtain his ulti

mate maximum salary of $230 (R. 45). On the other hand,

a principal placed on Track IV, Step 2 receives a salary

8

of $207 per month. After three years he will receive more

than the maximum obtainable on Track I, and his ultimate

salary is $305 per month, which he can obtain in 18 years

(R. 45). Therefore, if discrimination is to be avoided, it

is essential that it be eliminated in the initial placement on

the schedule (R. 48).

Placement on the new schedule was recommended to the

Superintendent by separate committees—one for white

teachers and one for Negro teachers. Each committee

operated independently with a Dr. Hunter serving on both

committees (R. 47). The present placement on the schedule

was approved, after some changes, by the Superintendent

of Schools (R. 47). Initial placement on the schedule is

determined by the Atlanta Board of Education in accord

ance with certain objectives and certain subjective criteria

which are set out in paragraph I of Exhibit 14—Procedures

for Applying the New Salary Schedules for Elementary and

High School Teachers. Advancement on the schedule is

also determined by the Atlanta Board of Education based

upon certain objective and subjective criteria which are set

out in paragraph 2, subsection 4 of Exhibit 14. The regu

lations provide that any teacher dissatisfied with her place

ment on the schedule may appeal to the Superintendent for

reconsideration (see par. 4, Exhibit 14). A Committee on

Appeals, advisory to the Superintendent, is given original

jurisdiction in any appeal, but its services are not avail

able to the aggrieved teacher (par. 4, Exhibit 14 and R.

82).

Appeal to the Atlanta Board to review the action of the

Superintendent is provided in paragraph 5, Exhibit 14.

Such appeal must be made in writing to the Atlanta Board

of Education within ten days of the action of the Superin

tendent (par. 5, Exhibit 14). There is no provision for a

hearing before the Atlanta Board of Education, for repre

9

sentation by counsel, for the presentation of evidence or

witnesses (par. 5, Exhibit 14).

Petitioner was placed on the new salary scale at the

same salary he had received under the old dual and admit

tedly discriminatory salary schedule (R. 47).

Although the findings of the trial court on the merits

were not disputed by the Court of Appeals, and the cause

is here solely on the question of whether petitioner’s suit

was premature in that he failed to exhaust certain state

administrative remedies, a brief review of the findings of

the trial court will be helpful to the Court, we submit, in

determining whether the writ herein sought should be

granted.

At the trial voluminous testimony was taken. The trial

court found that while the operation of the schedule

adopted by the Atlanta Board was “ complicated and their

provisions overlapping, and, as shown by the evidence, little

understood by defendants or teachers, they * * * are not

on their face discriminatory and only become so, if ad

ministered in a discriminatory manner” (R. 48). Both

petitioner and respondents employed the services of quali

fied statisticians. Petitioner’s statistician, in reaching his

conclusions, took a percentage of the Negro teacher popu

lation and compared it with a percentage of the white. This

is called the sampling method. Respondents objected to

the bases from which the statistician for the petitioner

worked. The court concluded, however, that if the methods

used by the latter had materially and erroneously affected

the conclusions reached, the discrepancies could easily have

been pointed out Avith tables asserted to be correct by the

respondents on an analysis of the whole population (R.

52). No such tables were presented and, therefore, the

court found that the statistics of the petitioner were “ rea

sonably correct” and presented “ conclusions which, after

10

allowing for a considerable margin of error and for reason

able scope in the exercise of a fair discretion based upon

subjective qualifications * # * , may be properly used in

the consideration and determination of the issue as to

whether or not discrimination because of race or color has

been shown” (E. 52).

The white teacher is 4.6 percent years older than the

colored teacher. Eighty-three percent of the white teachers,

as compared to 76 percent of the Negro teachers, have been

elected to tenure. The white teacher has 17.83 years of edu

cation, while the Negro teacher has 17.67 years. The median

total teaching experience in the Atlanta School System of

the white teachers was 18.5 years, and the Negro teachers

15.4 years. Total average teaching experience was 20.2

years for the whites and 16.8 years for Negroes (E. 59-60).

The trial court found that 78.1 percent of the white high

school teachers received more than $189 per month basic

salary, and 21.9 percent received $189 or less; whereas 1.5

percent of the Negroes received more, and 98.5 percent re

ceived less than $189 per month 2 (E. 57). That 54.2 percent

of the Negro high school teachers are on Track I, 16.6 per

cent on Track II, 25 percent on Track III and 4.2 percent on

Track IV ; whereas, 4.4 percent of the white teachers are on

Track 1 ,12.4 percent are on Track II, 14.3 percent on Track

III and 68.9 percent are on Track IV. Thus, the majority of

the Negro teachers are in Track I (E. 57) with an ultimate

maximum salary of $165 per month (E. 46), and the ma

jority of the white teachers are on Track IV (E. 57) with an

ultimate maximum salary of $231 per month (E. 46). In

terms of comparative qualifications, the record shows that

58 percent of the white teachers have Masters degrees and

2 The findings were 99.5 percent, but this, apparently is in error

and would amount to more than 100 percent.

11

36 percent have A.B. degrees; whereas 41 percent of the

Negroes have Masters degree and 50 percent have A.B.

degrees (R. 57).

The court also found that all the colored principals in

the elementary schools received less than $214 per month,

whereas only 17.1 percent of the white teachers received as

little as $214 per month. The rest received more, up to a

maximum of $314 per month. All the Negro principals are

on Tracks I and I I ; whereas only 16.7 percent of the white

elementary principals are on Track II, 25 percent on Track

III, 58.3 percent on Track IV and none on Track I (R. 58).

As to their comparative qualifications, the court found that

66.7 percent of the white elementary principals have Mas

ters degrees, while 80 percent of the Negro teachers hold

such degrees; 33.3 percent of the white principals have

A.B. degrees, while 20 percent of the Negroes hold such

degrees (R. 58).

With regard to elementary school teachers, 71.5 percent

of the white teachers receive over $139 per month, but not

over $214, while 28.5 percent receive less than $140 per

month. 95.2 percent of the Negro teachers receive less than

$140, while 4.8 percent receive between $140 and $164. 96.5

percent of the Negro elementary school teachers are on

Tracks I and II, 3.5 percent on Tracks III and I V ; while

25.6 percent of the white teachers are on Track II, 18.1 per

cent on Track III and 56.4 percent on Track IV and none on

Track I (R. 58). With respect to their academic qualifica

tions, 26 percent of the white teachers have Masters degrees.

42 percent A.B. degrees and 29 percent two years normal

training. As to Negroes, 5 percent have Master degrees, 73

percent have A.B. degrees and 21 percent have two years

normal training (R. 58). With respect to experience, 23

percent of the white high school teachers have had five years

12

experience or less, while 41 percent of the Negro high

school teachers have five years or less experience. As to

the white elementary teachers, 35 percent have five years

or less, while 53 percent of the Negro teachers have five

years or less experience (E. 59).

With regard to study increments: 87.8 percent of the

white elementary principals and 75 percent of Negroes have

earned increments; 36.6 percent of the white principals and

50 percent of the Negro principals have earned five incre

ments; 42.4 percent of the white elementary teachers have

increments, 20 percent of them having as many as five; while

29.3 percent of the colored elementary teachers have earned

increments, 16.9 percent as many as five. Each increment

entitles the teacher to a $5 per month permanent increase

(R. 59).

The court concluded that making allowances for error

and for the operation of subjective qualifications which de

termine the fitness of the teacher that discrimination had

been proved, and, therefore, ordered the writ to issue.

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit in reversing the judgment of the trial court based

its decision on the existence of a state administrative

remedy which had not been pursued (R. 70, 80, et seq.).

The court was of the opinion that petitioner should have ap

pealed both to the Atlanta Board and to the State Board of

Education (R. 83). The court further found that the appeal

to the State Board existed at the time the suit was filed, and

that appeal to the Atlanta Board was first created in June,

13

1944 (R. 83),3 after institution of the present suit. Since

relief sought related to discrimination at the time of the de

cree, the court concluded petitioner should have been re

quired to have pursued the administrative remedy available

at that time (R. 84). The Court, however, did not feel that

petitioner’s failure to exhaust administrative remedies

ousted the trial court of jurisdiction warranting dismissal,

of this action (R, 84), because the failure to appeal to the

State Board was not raised in the respondent’s motion to

dismiss, and appeal to Atlanta Board of Education, pur

suant to regulations now in effect, was not made available

until after institution of this suit (R. 84). The cause was

remanded to the district court to there remain pending for

a reasonable time to permit the exhaustion of administra

tive remedies (R. 85). The opinion of the Court of Appeals

has not as yet been officially reported.

Petition for rehearing was filed on January 27, 1950

(R. 94), and overruled on February 6, 1950 (R. 95).

Jurisdiction.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1254, this being a case involv

ing rights secured under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. In his complaint and

throughout the entire proceedings petitioner has asserted

that the action of respondents in paying him and other

Negro teachers and principals a lower salary than is paid

to white teachers and principals of equal qualifications and

experience is a denial of the equal protection of the laws

guaranteed by the federal constitution.

3 Actually the new schedule did not go into effect until September,

1944 as found by the trial court when the classification had been

completed (R. 47, 37).

14

Question Presented.

I.

Does the state provide an administrative remedy

which is required to be exhausted prior to restort to the

federal courts for relief and which necessitates the

setting aside of the judgment of the trial court pending

petitioner’s appeal to the Atlanta and State Boards of

Education?

Reasons Relied Upon for Allowance of the Writ.

I.

The principle of exhaustion of administrative remedies

does not require petitioner to pursue the suggested remedy

of appeal to the State Board of Education for the reason

that the State Board is without statutory jurisdiction or

authority to grant petitioner the relief sought in this action.

The relief which petitioner seeks is from the discriminatory

practices of the Atlanta Board of Education which cannot

be corrected by the State Board of Education in view of

the autonomous structure of the Atlanta School System and

the limited authority of the State Board with respect to the

payment of salaries of school teachers in the Atlanta public

school system. Final authority to fix the salary of petitioner

and the class he represents rests not within the State Board

of Education but solely with the Atlanta Board of Edu

cation (§32-609, Ga. Code Ann., Acts 1947, pp. 882, 884;

Acts 1947, pp. 668, 669; §32-602, Ga. Code Ann., Acts 1937,

pp. 882, 883; §32-613, Ga. Code Ann., Acts 1937, pp. 882,

886; § 36-615, Ga. Code Ann., Acts 1937, pp. 882, 887; Acts

1947, pp. 206, 216; Acts 1947, pp. 668, 670; §32-616, Acts

1937, pp. 882, 888; §32-910, Acts 1919, p. 324; Acts 1947,

15

pp. 1189, 1190; § 32-1010, Acts 1919, p. 352, Acts 1947, pp.

1189, 1191. See also Fordham v. Harrell, 197 Ga. 135, 28

S. E. 2d 463 (1943); Downer v. Stevens, 22 S. E. 2d 139

(1942); Carter v. Johnson, 186 Ga. 167, 197 S. E. 258

(1938).)

II.

The procedure provided for appeal to the Atlanta Board

of Education, as set out in paragraph 5 of Exhibit 14 (Pro

cedure for Applying the New Salary Schedules for Elemen

tary and High School Teachers), at best provides a pro

cedure for rehearing or reconsideration since the Board

determines, in the first instance, the teacher’s salary and

his placement on the schedule. (See Exhibit 14, pars. 1, 2;

§32-605, Ga. Code Ann., Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883.) There

fore, to require petitioner to follow the remedy provided in

paragraph 5 of Exhibit 14 prior to seeking judicial relief

is in direct conflict with the decision of this Court in Levers

v. Anderson, 326 U. S. 219.

III.

The procedure provided for appeal to the Atlanta Board,

as the trial court pointed out (R. 61), does not provide for

an appeal to a disinterested party, but to the very agency

guilty of effectuating the wrong complained of. Petitioner,

and all the Negro teachers and principals in the school sys

tem of Atlanta, complained to the Atlanta Board and it has

failed to discontinue these discriminatory practices. The

principle that administrative remedies must be pursued

prior to resort to the courts does not require an appeal to

be taken to the very body which perpetuates the wrong on

which the cause of action is based. Steele v. Louisville &

Nashville R. Co., 323 U. S. 192; Tunstall v. Brotherhood of

Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210.

16

IV.

Under Georgia law, as defined by the highest court of

the state, the statutory provisions for appeal to county and

state boards of education have been construed as not bar

ring direct resort to courts to compel the proper discharge

of official duty. County Board of Education v. Young, 187

Ga. 666, 1 S. E. 2d 739 (1939); Bryant v. Board of Educa

tion, 156 Ga. 688, 119 S. E. 601 (1923). Hence, the adminis

trative remedy provided is, under Georgia law, at best a

permissive and not a mandatory remedy. Therefore, the

decision of the Court of Appeals requiring the exhaustion

of this remedy is in direct conflict with the opinion of this

court in Moore v. Illinois Central Railroad Co., 312 U. S.

630, where the pursuit of administrative remedy was

deemed to be required only where the statute made such

pursuit mandatory. Where the remedy provided was a

permissive one, this Court there held that it need not be

pursued prior to the institution of action in the federal

courts.

V.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is in apparent con

flict with the principles enunciated by the Court of Ap

peals for the Ninth Circuit in Trans-Pacific Airlines v. Ha

waiian Airlines, 174 F. 2d 63 (C. C. A. 9th 1949). In that case

the Ninth Circuit held that the exhaustion of administrative

remedies was required only where the question to be deter

mined required expert knowledge and administrative dis

cretion. In this case the sole question presented is whether

the Atlanta Board of Education discriminated against Negro

teachers in the payment of salaries solely on the basis of

race and color in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The federal courts are better equipped to determine that

question than any administrative agency of the state.

17

VI.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals conflicts with the

principles of this Court announced in Oklahoma Natural

Gas Co. v. Russell, 261 U. S. 290; Pacific Telephone and

Telegraph Co. v. Kuykendall, 265 U. S. 196; Porter v. In

vestors Syndicate, 286 U. S. 461; Aircraft & Diesel Equip

ment Corporation v. Hirsch, 331 U. S, 752, to the effect

that the presence of constitutional questions coupled with

a sufficient showing of the inadequacies of the prescribed

administrative remedy and threat of irreparable injury

flowing from the delay incident to following the prescribed

procedure were sufficient to dispense with exhausting the

administrative process before instituting judicial action.

VII.

The procedure provided in paragraph 5, Exhibit 14 for

appeal to the Atlanta Board of Education for review of

the teacher’s placement on the salary schedule is not con

sistent with requirements of due process of law. The time

limit for effecting such review is unreasonably short and

is, apparently, designed to prevent rather than to permit

adequate opportunity for a full and fair hearing. The pro

cedure provides a period of only ten days for taking an

appeal to the Atlanta Board of Education. Since the very

nature of petitioner’s grievance is based upon a practice

of racial discrimination, it would be necessary for him to

have access to the voluminous files and records of the At

lanta Board; to study and analyze these files and records;

and to make other investigation in order to be in a position

to submit adequate proof of his claim of discriminatory

treatment. This was amply demonstrated by the vol

uminous evidence which was presented at the trial on the

merits to prove discrimination in the administration of

the new salary schedule. Obviously ten days is too short a

time within which to make such preparation. Munn v. Des

Moines National Bank, 18 F. 2d 269 (C. C. A. 8th 1927).

18

The remedy provided is inadequate for the reason that

the so-called right of appeal from an unjust classification

of the Superintendent falls short of the requirements of

due process under the Fourteenth Amendment. There is

no clear right to a hearing. No provision is made in the

Board’s appeal procedure for the presentation of evidence

by the aggrieved teacher, nor for disclosure by the Super

intendent of the basis for the action taken. There is a

complete absence of the other procedural safeguards re

quired by due process. No provision is made for the re

butting of evidence or representation by counsel. In short,

the prescribed administrative remedy which petitioner is

told to exhaust does not afford him an opportunity to pro

tect his constitutional right here asserted, but constitutes

an opportunity for the Board to make a decision without

evidence and without a ‘ ‘ hearing ’ ’ in the due process sense.

United States v. Morgan, 298 U. S. 468; Morgan v. United

States, 304 U. S. 1 (1938); Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public

Utilities Comm., 301 U. S. 292; Kansas City So. Ry. Co. v.

Ogden Levee Dist., 15 F. 2d 637 (C. C. A. 8th 1926); Munn

v. Des Moines National Bank, supra; Colyer v. Skeffington,

265 Fed. 17 (D. Mass. 1920).

IX.

The new scheme and schedule, now employed by the At

lanta Board of Education, is an attempt to continue the

policy, custom and usage, practiced under the old dual

salary schedule, of paying to Negro teachers and principals

of equal qualifications and experience less salary than is

paid to white teachers and principals solely on account of

race and color, under a device so ingenious and complicated

as to avoid the reach of the Fourteenth Amendment.

VIII.

19

Conclusion.

W herefore, it is respectfully submitted that this peti

tion for writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit should be granted.

A. T. W alden,

Oliver W. H ill,

T hurgood Marshall,

R obert L. Carter,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

H oward J enkins, J r .,

J ames M. Nabrit,

Of Counsel.

Dated: May 5,1950.

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949

N o............

Samuel L. Davis, Individually and on

Behalf of Others Similarly Situated,

Petitioner,

vs.

E. S. Cook, et al., Constituting the Board

of Education of the City of Atlanta.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR W R IT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

Opinions of the Courts Below.

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit may be found at page 70 of this record

and is not yet officially reported. The findings of fact and

conclusions of law and judgment of the United States Dis

trict Court for the Northern District of Georgia begin at

page 40 of the record and is officially reported in 80 F.

Supp. 443.

Jurisdiction.

Jurisdiction of this Court rests upon Title 28, United

States Code, Section 1254. The United States District

Court for the Northern District of Georgia entered judg-

21

22

ment for petitioner on December 16, 1948. Judgment was

reversed by the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit on December 28, 1949. Petition for rehearing

was filed on February 27, 1950 (E. 89) and was overruled

February 6, 1950 (E. 95).

Statement of the Case.

The pertinent facts involved in this case have been set

out in the petition itself and, therefore, will not be restated

at this time.

Errors Relied Upon.

The United States Coart of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit erred in reversing the judgment of the United

States District Court for the Northern District of

Georgia, which had entered a decree enjoining and

restraining respondents from discriminating in the pay

ment of salaries against petitioner and other Negro

teachers and principals in the public schools in Atlanta,

Georgia, and from paying petitioner and other Negro

teachers and principals in said schools less salary than

is paid to white teachers and principals of equal quali

fications and experience solely on account of race and

color.

The Court erred in reversing the judgment of the

trial court on the grounds that petitioner should have

appealed to the Atlanta Board of Education prior to

seeking relief in the federal courts.

The Court erred in reversing the judgment of the

trial court on the grounds that petitioner should have

appealed to the State Board of Education prior to seek

ing relief in the federal courts.

23

A R G U M E N T .

I.

Administrative remedies need not be pursued prior

to resort to federal courts unless mandatory in nature.

In County Board of Education v. Young, 187 Ga. 664, 1

S. E. 2d 739 (1939) the Supreme Court of Georgia had be

fore it the question whether a direct proceeding against the

County Board of Education could be maintained by a

teacher for restoration of her former status as principal and

for her back salary. Under Section 32-910 Georgia Code

Annotated, county boards of education are made tribunals

for hearing and determining local controversies with respect

to the construction and administration of school laws, with

a right of appeal to the State Board of Education. The

Court held that even if the statute were to be construed as

reaching the instant controversy, such construction would

not preclude a direct judicial proceeding against the Board

to compel a proper discharge of official duty. (To the same

effect see Bryant v. Board of Education, 156 Ga. 688, 119

S. E. 601 (1923).) Counsel for petitioner has discovered

no subsequent decision of the state court limiting, restrict

ing or repudiating the views expressed in this case.

Thus, prior to seeking judicial intervention to compel a

proper discharge of official duty, one is not required under

Georgia law to follow statutory procedures providing for

appeal to county and state boards of education. This case

raises a more fundamental question concerning proper

official conduct than was presented in the Young case, supra.

Petitioner, therefore, is not required to pursue any appeals

to the Atlanta or State Board of Education, which may be

provided, before his cause becomes ripe for judicial deter

mination.

24

In Moore v. Illinois Central Railway C o 312 U. S. 630,

this Court held that use of the administrative machinery

provided under the Railway Labor Act for the settlement

of disputes was not a necessary prerequisite to court action.

In County Board of Education v. Young, supra, statutory

appeals to county and state boards of education are simi

larly construed. Even if the Court of Appeals is correct in

concluding that an administrative machinery is available to

redress the wrongs of which petitioner complains, since

utilization of this machinery is not a necessary prerequisite

to court action, petitioner was entitled to federal relief

without being required to first avail himself of the admin

istrative process. We submit, therefore, that the judgment

of the trial court was correct and should be affirmed.

II.

The nature of petitioner’s cause is such as to require

dispensing with the pursuit of administrative remedies

and immediate judicial determination.

Petitioner is here complaining of irreparable injury.

He instituted this suit in equity seeking a declaration of

his rights and a decree enjoining and restraining respon

dents from discriminating against him and other Negro

teachers and principals solely because of race and color

in the payment of salaries. The discriminatory treatment

on which his cause of action rests has continued since be

fore 1941 when a petition requesting the Atlanta Board of

Education to cease its discriminatory practices was filed

on behalf of the Negro teachers and principals in the At

lanta school system.

The Atlanta Board of Education cannot pay to Negro

teachers and principals less salary than is paid to white

teachers and principals of equal qualifications and ex

25

perience without violating the guarantees of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Alston v. School Board, 112 F. 2d 992 (C. C. A.

4th 1940); cert, denied, 311 TJ. S. 693; Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U. S. 356.

The relief, which the trial court granted, does not reach

the past conduct of the Atlanta Board of Education, but

relates only to future action. Further delay in the settle

ment of this dispute will prolong the harm which petitioner

and other Negro teachers have suffered over a long period

of years. Petitioner has conclusively proved that he and

other Negro teachers and principals are being discrimi

nated against in the administration of the salary scheme

and schedule under which the Atlanta Board of Education

is now operating. He is entitled, therefore, to judgment

declaring the Board’s action to be a denial of the equal

protection of the laws', Yick Wo v. Hopkins, supra, and to

a decree enjoining further discrimination. Alston v. State

Board, supra.

Under Georgia law, as we have pointed out above, statu

tory provisions providing for appeal to county and state

boards of education do not bar direct court action. County

Board of Education v. Young, supra. In view of the auton

omy given independent school systems and the limited

statutory authority which the State Board of Education

may exercise with respect to teachers’ salaries, its au

thority to grant relief is extremely dubious at best. See

Downer v. Stevens, 22 S. E. 2d 139 (1942); Fordham v.

Harrell, 197 Ga. 135, 28 S. E. 2d 463 (1943). In fact, we

believe that the statutes and cases necessitate the conclu

sion that the State Board of Education is without jurisdic

tion and authority to grant petitioner relief herein sought.

Under these circumstances, we submit, the rule which

this Court applied in Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Bussell,

261 U. S. 290; Pacific Telephone £ Telegraph Co. v. Kuy

2 6

kendall, 265 U. S. 196; Porter v. Investors Syndicate, 286

U. S. 461, and restated with approval in Aircraft & Diesel

Equipment Corp. v. Hirsch, 331 IT. S. 752 governs this action.

In those cases, this Court established the principle that the

requirement that administrative remedies be exhausted

prior to resort to federal courts would be dispensed with

where there was present a constitutional question, a show

ing of the inadequacy of the prescribed administrative re

lief and a threat of irreparable injury flowing from the

delay incident to a pursuit of the administrative procedure.

In Aircraft & Diesel Equipment Corp v. Hirsch, supra, note

38, at page 773, it was pointed out that this rule had been

most frequently applied with respect to state administra

tive action. We submit that this case presents all factors

requiring application of that rule and that the judgment

of Court of Appeals in requiring petitioner to utilize the

administrative process before seeking the intervention of

the federal court was in error and should be reversed.

III.

The State Board of Education is without statutory

jurisdiction or authority to grant petitioner the relief

he seeks.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, that petitioner

should have invoked the aid of the State Board of Educa

tion before being permitted to seek relief in the federal

court, we submit, wTas based upon an erroneous view of the

law of the State of Georgia. The State Board of Educa

tion has no jurisdiction or authority to order the Atlanta

Board of Education to discontinue its policy, custom and

usage of paying Negro teachers less salaries than it pays

white teachers of equal qualifications and experience and

performing substantially the same functions.

27

Section 32-601, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883)

empowers the State Board of Education to equalize the

educational opportunities of all children of school age

throughout the State of Georgia.

Section 32-604, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883)

establishes several county and independent school systems

as local units of administration through which the State

Board is to operate in equalizing educational advantages.

Section 32-608, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 884)

directs the State Board of Education to divide the various

local units of administration into five groups on the basis

of population.

Section 32-609, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 884;

Acts 1947, pp. 668, 669) empowers the State Board of Edu

cation to determine for each group the minimum number

of teachers to be employed for the minimum school term

of seven months per year required under Section 32-602,

Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 883).

Section 32-610, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 885)

provides that all teachers employed in the public school

system of the state shall hold a state’s certificate issued

by the State Board.

Section 32-611, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 886)

expressly states that local school units are not prohibited

from providing educational advantages in addition to those

prescribed or that may be prescribed by the State Board of

Education or from making rules for the government of such

local systems not in conflict with the rules prescribed by

the State Board.

Section 32-613, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882-886)

directs the State Board of Education to annually fix a sched

ule of the minimum salaries to be paid to the teachers of

2 8

the various classes prescribed by them out of the public

school funds of the state; and further provides that the

salary schedule shall be uniform for each of the classes of

teachers fixed by the State Board.

Section 32-614, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 886)

provides that the common school funds of the state shall be

used by the State Board to pay to teachers in the public

schools of the state for not less than seven months in each

school year in accordance with the salary schedule pre

scribed by the State Board of Education.

Section 36-615, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882, 887;

Acts 1942, pp. 206-216; Acts 1947, pp. 668-670) empowers

each local unit to operate its school for a period longer than

the seven month school year established by statute and to

supplement the state schedule of salaries and employ teach

ers in addition to the minimum number prescribed by the

State Board of Education. It further expressly states that

the rate of pay of all teachers must not be less than the

minimum salaries set by the State Board of Education.

Section 32-616, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882-888)

empowers the State Board to fix at the beginning of each

year the minimum schedule of teachers’ salaries for the en

suing year and to determine the minimum number of teach

ers which may be employed for each local unit.

Pursuant to this statutory authority, the State Board

of Education classifies teachers in the Atlanta School Sys

tem on the basis of their types of certificates and years of

training (see Exhibits 12 and 30). It determines the mini

mum number of teachers which the Atlanta Board of Edu

cation may employ and prescribes a minimum rate of pay

and allocates state funds to the Atlanta Board on this basis.

The Atlanta Board of Education has exclusive authority to

employ teachers (see Fordham. v. Harrell, supra; Carter

29

v. Johnson, supra), and the salaries it pays are considerably

higher than the minimum rate prescribed by the State

Board of Education (compare Exhibits 12 and 30, State

Salary Schedule for Teachers, and Exhibit 13 and B. 45, 46,

Salary Schedule in Atlanta Public Schools). Funds to pro

vide these additional advantages are raised locally pursuant

to authority granted in Section 32-1111, Ga. Code Ann.

(Acts 1919, p. 340; Acts 1946, pp. 206, 211). The Atlanta

Board and it alone is in sole and exclusive control of these

funds. Downer v. Stevens, supra. In addition the Atlanta

Board of Education provides for a teacher classification

considerably different from that which the State Board

prescribes. The Atlanta Board of Education determines

actually and finally the salaries which each teacher is to

receive.

Under the statute all that the State Board can require

is that the teachers employed in the Atlanta School System

do not receive a rate of pay less than the minimum which

has been prescribed in the state salary schedules. Statutory

authority is expressly given to the Atlanta Board of Edu

cation to pay to the teachers higher salaries, and as long

as its rate of pay meets the minimum standard which the

State Board of Education prescribes, that Board is without

jurisdiction or statutory authority to tell the Atlanta Board

of Education what salary it must pay the teachers in its

employ.

Thus, it is difficult to perceive how petitioner could ob

tain relief from the State Board of Education since he

and the other Negro teachers and principals employed in

the Atlanta School System are paid more than the minimum

which the state requires. It is, therefore, submitted that

the State Board of Education cannot grant petitioner the re

lief which he seeks and, therefore, an appeal to the State

Board of Education would be futile.

30

Further, Section 32-910 (Acts 1919, p. 324; Acts 1947,

pp. 1189,1190) and Section 32-1010 (Acts 1919, p. 352; Acts

1947, pp. 1189, 1191) which provide for appeal to the State

Board of Education in general controversies determined by

county boards of education and specific controversies in

volving the suspension of teachers would appear to negate

an intent on the part of the state legislature to give the

State Board of Education under Section 32-414 such overall

authority over local school systems which the Court of Ap

peals believed it to have. The State Board’s role is merely

to supervise generally the public school systems of the state

and to require them to meet certain uniform minimum

standards. Except for this limited authority, power and

responsiblity for the conduct of the schools rest with the

local school systems. See Boney v. County Board of Edu

cation, 45 S. E. 2d 442 (1947); Fordham v. Harrell, supra.

Thus, it is clear that the State Board cannot grant petitioner

relief herein sought, and to require him to appeal to that

agency is to require him to do a useless and futile act.

IV.

The procedure provided for appeal to the Atlanta

Board of Education is in the nature of a petition for

rehearing or reconsideration by the Board and, hence,

need not be exhausted prior to resort to the federal

courts.

Section 32-605, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937, pp. 882-883)

provides that teachers are to be elected by the Atlanta

Board of Education on the recommendation of the Super

intendent of Schools. The procedure outlined in Exhibit

14 for the application of the salary schedule now in effect

in the Atlanta Public School System further provides that

the Board of Education shall determine the salaries to be

paid and the group in which the teacher shall advance in

31

the schedule on the recommendation of the Superintendent.

(See par. 1, subsection 2, par. 2, subsection 1 of Exhibit

14—Procedure for Applying the New Salary Schedule for

Elementary and High School Teachers.) Thus, the Atlanta

Board of Education is required by statute and by its own

regulations to hire the teacher, determine his salary and

his placement on the salary schedule in the first instance.

It is incorrect, therefore, to conclude as apparently the

Court of Appeals concluded, that the determination of the

teachers’ salaries and his placement on the salary schedule

is made by the Superintendent of Schools independent of

the Atlanta Board of Education. The Superintendent of

Schools merely recommends. The determination and place

ment is and must be made by the Atlanta Board of Educa

tion. Thus, to require petitioner to pursue the remedy pro

vided in paragraph 5 of Exhibit 14 prior to seeking judicial

relief is to require him to go to the Atlanta Board of Edu

cation and ask them to reconsider their initial action in

fixing his salary and his placement on the schedule. At

best this would be a procedure in the nature of a petition

for rehearing. This Court in Levers v. Anderson, 326 U. S.

219 at p. 222 said the rule that “ no one is entitled to judicial

relief for a supposed or threatened injury * * * does not

automatically require that judicial review must always be

denied where rehearing is authorized but not sought.”

There is no statutory or constitutional requirement of the

State of Georgia which makes it mandatory for petitioner

to seek a rehearing before the Atlanta Board of Education

prior to seeking judicial intervention. There is no con

stitutional or statutory authority to indicate that this was

the intent of the legislature. It would therefore follow that

the principle of Levers v. Anderson, supra, should apply to

this case, and that petitioner would not be required to fol

low the procedure outlined in Exhibit 14 for seeking a re

view by the Atlanta Board of Education prior to seeking

relief in the federal courts.

32

V.

The procedure provided for appeal to the Atlanta

Board of Education fails to satisfy the minimum re

quirements of due process of law.

1.

The remedy provided under paragraph 5, Exhibit 14 for

appeal to the Atlanta Board of Education is inadequate for

the reason that the time limit for perfecting such an appeal

is unreasonably short and is designed to prevent rather

than permit adequate opportunity for a full and fair

hearing.

The Atlanta Board of Education is not subject to the

control of the State Board of Education with respect to fix

ing the total compensation payable to teachers in the At

lanta school system, except that it cannot pay less than the

minimum which the State Board prescribes. Thus, the pro

cedure outlined in paragraph 5, Exhibit 14 provides the

only administrative remedy under which petitioner may

conceivably obtain the relief which he now seeks. It is to

be remembered that this procedure was not available to

petitioner at the time this suit was filed in July, 1943, but

became available one year after institution of this action.

Under the procedure described in Exhibit 14, which may

be utilized when a teacher is dissatisfied with his classifi

cation and placement on the salary schedule, a Committee

on Appeals, advisory to the Superintendent, is given au

thority to consider appeals referred to it by the Superin

tendent (see par. 4 of Exhibit 14). However, as the Court

of Appeals correctly indicated (B. 82), since the dissatisfied

teacher cannot invoke the services of this committee, it is

not a part of the machinery to be considered in the appli

cation of the doctrine of exhaustion of administrative

remedies.

33

Paragraph 5, Exhibit 14 provides that a teacher “ who is

dissatisfied with the action of the Superintendent on appeal

may request the Board of Education to review the same.

Such request shall be made in writing within ten days from

the action of the Superintendent” . This procedure allow

ing only ten days for taking an appeal to the Atlanta Board

of Education is totally inadequate.

In this case, for example, petitioner alleges discrimina

tory conduct on the part of the Atlanta Board in paying to

him and other Negro teachers and principals less salary

than is paid to white teachers and principals of equal quali

fications and experience. It would be necessary for him to

have access to the files and records of the Atlanta Board

for the purpose of study and analysis in order to compare

his position and the position of other Negro teachers and

principals on the scale with that of white teachers and prin

cipals of equal qualifications and experience. To sustain Ms

claim of discriminatory treatment on appeal to the Atlanta

Board of Education, it would be necessary for petitioner to

follow the same method which was used to prove discrimina

tion in the trial court, that is, the employment of a qualified

statistician with access to the records of the Board for study

and analysis. Only then will he be able to submit adequate

proof of his claim of discriminatory treatment.

As the trial court found, the operation of the salary

schedule is complicated and little understood by either the

respondents or the teachers (R. 48). To obtain factual proof

within the short time limit of ten days prescribed, sufficient

to prove the discriminatory treatment herein alleged, would

be virtually impossible. To require petitioner to pursue such

a remedy is, in fact, to deprive him of a right to a full and

fair hearing within the meaning of the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

34

The principle here enunciated is illustrated by Munn v.

Des Moines National Bank, 18 F. 2d 269 (C. C. A. 8th 1927).

In that case the court had before it the problem of deciding

whether a suit could be entertained in equity against the

application of a discriminatory state tax statute prior to

the exhaustion of administrative remedies. The gravamen

of the complaint asserted by the taxpayers was that the

records from which they would be able to obtain proof of

discrimination was not made available until a few days

prior to the scheduled hearing before the administrative

agency. The court entertained the suit because it concluded

that the shortness of time available to the taxpayers to

properly prepare for the administrative hearing made the

administrative remedy totally inadequate. There the court

said, at page 271, that an adequate “ remedy which will pre

vent the maintenance in this court of equity of these suits

must be ‘ as practical and efficient to the ends of justice and

its prompt administration as the remedy in equity’ ” .

In view of the fact that the ten days prescribed for ap

peal to the Atlanta Board of Education does not afford suf

ficient time for petitioner to assemble evidence essential to

prove the claimed discrimination, in effect, no administra

tive remedy is available to him. The rule requiring exhaus

tion of administrative remedies, therefore, does not apply

to the procedures set out in Exhibit 14 prescribing the

method of appeal to the Atlanta Board of Education.

2.

The many procedural shortcomings relating to peti

tioner’s opportunity to obtain a full and fair hearing under

the procedure presented in Exhibit 14, make it clear that

the machinery which respondents have established fails to

satisfy the minimum requirements of due process of law.

The regulations promulgated by the Board of Education

fail to indicate what rights a dissatisfied teacher has with

35

respect to the fundamental question of notice and oppor

tunity for a hearing. All that the regulations contemplate,

and all that the regulations provide is that in some manner

there may be a review by the Board of Education of the

action taken by the Superintendent at the request of a dis

satisfied teacher. No clear right to a hearing is set forth

or spelled out. Under the regulations no hearing, in fact,

is required.

There is a complete absence of other procedural safe

guards which this Court has said are essential to an ade

quate hearing before an administrative agency. No pro

vision is made for the presentation of evidence by the ag

grieved teacher, for the rebutting of evidence, nor for repre

sentation by counsel. There is no procedure prescribed

whereby the teacher can be advised of the bases of the

action taken by the Superintendent in placing him in one

position on the scale as compared with placing another

teacher of equal qualifications and experience and perform

ing the same duty on another position on the scale. The

regulations do not require that the Superintendent make a

record of the bases for her findings in the first instance.

In short, the regulations permit an ex parte determination

of the salary to be made without evidence, without disclosure

of the bases for making such a determination, without con

sultation with the teacher and without affording the teacher

an opportunity to be heard. Moreover, the Board is not

required to grant the aggrieved teacher a hearing, and

though it is charged with the responsibility of reviewing

the action of the Superintendent on an appeal by the

teacher, no procedural steps governing such review are set

forth in the regulations. It is clear, therefore, that this

procedure fails to meet the minimum requirements of due

process as understood and interpreted by this court. See

Londoner v. Denver, 210 U. S. 373; United States v. Morgan,

298 U. S. 468; Morgan v. United States, 304 U. S. 1; Ohio

36

Bell Telephone Co. v. Public Utilities Commission, 301 U. S.

292. See also Kansas City So. Ry. Co. v. Ogden Levee Dist.,

15 F. 2d 637 (C. C. A. 8th 1926); Colyer v. Skeffington, 265

Fed. 17 (D. Mass. 1920).

There is no necessity for the administrative hearing to

be governed by strict rules of courts of law, but reasonable

standards of justice and fair play must be assured. In the

light of the procedural shortcomings pointed out above, no

such safeguards are provided under the regulations which

respondents have promulgated.

In short, the administrative remedy which the Court of

Appeals states that petitioner is required to exhaust does

not afford him an opportunity to protect the constitutional

rights here asserted, but on the contrary constitutes an

opportunity for the Board to make its decision without evi

dence and without affording petitioner a hearing within the

meaning of due process of the law. The remedy being in

adequate petitioner was entitled to seek direct judicial inter

vention.

3.

As pointed out by the trial court, to require petitioner

to appeal to the Atlanta Board of Education would be to

require him to appeal not to a disinterested agency but to

the very body whose actions he is now seeking to have cor

rected (R. 61). This Court in Steele v. Louisville & N. R.

Co., 323 U. S. 192, and Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomo

tive Firemen & Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210 concluded that it

was not an essential prerequisite to federal action that a

complainant seek redress from the administrative agency

guilty of the wrong upon which his cause of action is based.

Therefore even if appeal to the Atlanta Board can be con

sidered adequate, since petitioner would be required to ap

peal to the very party guilty of the wrong upon which peti

tioner bases his complaint, petitioner is not barred from

proceeding directly in the federal courts.

37

Under Section 32-605, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts 1937) the

Atlanta Board has full authority and responsibility for the

hiring* of teachers in the Atlanta School System. The At

lanta Board is responsible for determining the teacher’s

salary and his placement on the salary schedule. The regu

lations themselves set out in Exhibit 14 expressly and speci

fically recognize and provide for the exercise of this au

thority in the Atlanta Board of Education (see pars. 1 and

2, Exhibit 14). All the Superintendent may do is to

recommend. Responsibility rests solely with the Atlanta

Board.

As the Court of Appeals has construed, these regula

tions, initial placement on the schedule and determination

of the teachers’ salary is made by the Superintendent of

Schools independent of the Atlanta Board of Education.

This the Superintendent of Schools is not empowered to do

under the statute. Section 32-605, Ga. Code Ann. (Acts

1937); Fordham v. Harrell, supra; Carter v. Johnson,

supra; and if the regulations provide for such independent

action on the part of the Superintendent of Schools then

such regulations are invalid.

For these reasons, we submit, the Court of Appeals was

in error in holding that petitioner was required to appeal to

the Atlanta Board under the procedure prescribed.

VI.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals in this case is

in apparent conflict with the Court of Appeals of the

Ninth Circuit.

In this case the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

held that the granting of federal relief was premature in

view of the fact that petitioner had failed to avail himself

of the state administrative remedies. Petitioner is here

seeking a declaration of his right to be free of discrimination

in the payment of salaries by the Atlanta Board solely be

cause of his race and color. He further seeks to enjoin and

restrain respondents from continuing their policy, custom

and usage of discriminating against him and other Negro

teachers and principals. The question presented does not

involve the application of administrative discretion. Nor

does it require for its determination any special or expert

knowledge with which the administrative agency may be

peculiarly equipped. Where racial discrimination exists it

is violative of the Federal Constitution. Hence, questions

of administrative discretion cannot be determinative of a

problem of that nature.

Racial discrimination in the payment of teachers’ sal

aries has been proved by petitioner in the trial court. It is

within the special province of the federal courts to deter

mine whether discriminatory treatment is practiced by state

officials and to grant appropriate relief from such wrongful

conduct. See United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304

U. S. 144; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1. Yet the Court

of Appeals construed the rule requiring the exhaustion of

administrative remedies prior to resort to federal courts as

being automatically applicable in this case without regard

to these factors.

In Trans-Pacific Airlines v. Hawaiian Airlines, 174 F. 2d

63 (C. C. A. 9th 1949), the Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit held that the rule requiring exhaustion of adminis

trative remedies is applicable only in those cases where solu

tion of the problem requires familiarity with complicated