Pre-Trial Memorandum of Plaintiffs Ralph Gingles et. aI.

Public Court Documents

July 21, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Pre-Trial Memorandum of Plaintiffs Ralph Gingles et. aI., 1983. 5094c351-d492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3551126f-a13b-46db-a4f5-620351f46cbe/pre-trial-memorandum-of-plaintiffs-ralph-gingles-et-ai. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

.qL

/

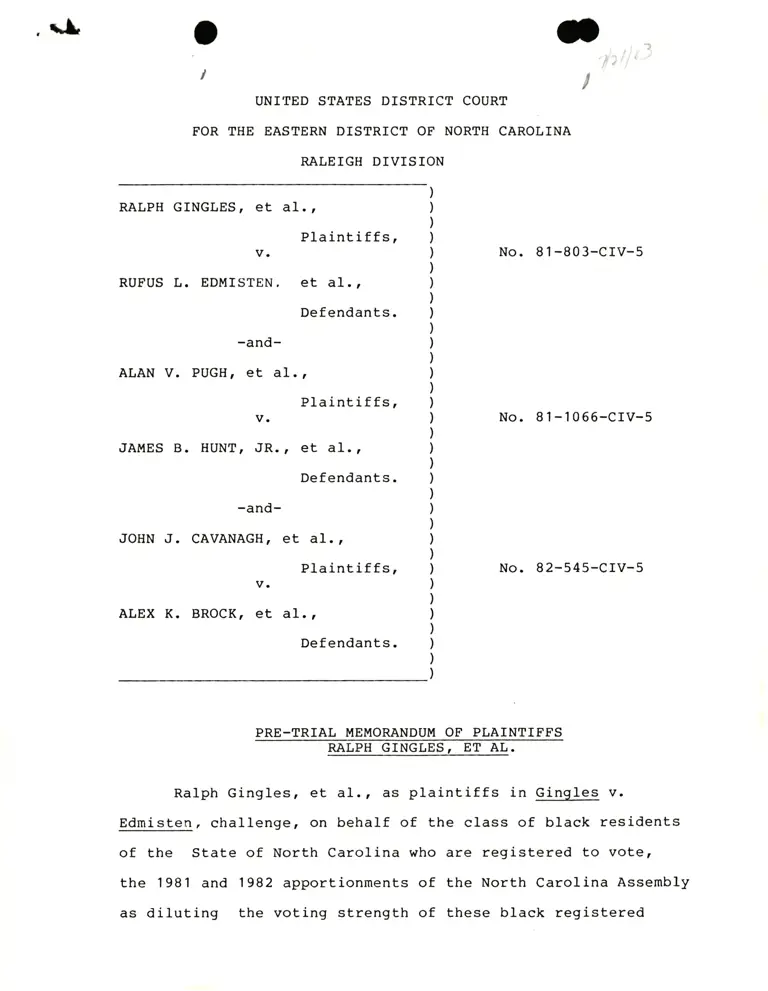

FOR

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

RALPH GINGLES, €t dI.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

RUFUS L. EDMTSTEN. et dI.,

Defendants.

-and-

ALAN V. PUGH, €t d1.,

No.81-803-CIV-5

No. 81-1066-CIv-5

No. 82-545-CIV-5

v.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR.,

-and-

JOHN J. CAVANAGH, €t dl.,

Plainti ffs,

et aI.,

Defendants.

Plaintiffs,

€11. ,

Defendants.

v.

etALEX K. BROCK,

PRE-TRIAL MEMORANDUM OF PLAINTIFFS

RALPH GINGLES ET AL.

Ralph Ging1es, €t dI., as plaintiffs in Gingles v.

of the class of black residentsEdmisten, challenger oD behalf

of the State of North Carolina who are registered to vote,

the 1981 and 1982 apportionments of the North Carolina Assembly

as diluting the voting strength of these black registered

,7)

voters in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, amended June 29, L982, 42 U.S.C. S 1973 (hereafrer

Section 2 or Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act), the

Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution, and 42 U.S.C. S 1983. The parries have

stipulated that this court has jurisdiction over this acEion

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. S 1973(f) and 28 U.S.C. SS 1331 and

L343(a) (3) and (a) (4), and that a three judge courr is

properly convened pursuant to 28 U.S.C. S 2284(a).

I. Statement of the Facts

In 1981 the North Carolina General Assembly enacted

apportionments of the North Carolina House of Representatives

and Senate in light of the 1980 census. The result of this

initial apportionment, in July 1981, was a plan which used

Large multi-member districts across the state, had no majority

black districts, and had population deviations above 207". In

compliance with the provisions of the NorEh carolina Consti-

tution, Article rr S3(3) and 55(3) prohibiting rhe division of

counties in the creation of a legislative district, each dis-

trict was composed of whole counties.

rn October, 1981, after this lawsuit wa.s fi1ed, challenging

inter alia the fact that Article rr S3(3) and S5(3) were never

precleared, the State submitted the North Carolina Constitution's

prohibition against dividing counties to the Attorney General

of the united states for preclearance pursuant to 55 of the

Voting Rights Act of L965, amended, 42 u.s.c. 91973c (hereafter

SecEion 5). While awaiting a decision of the Attorney General,

-2-

,a\

the House, but not the Senate, enacted a second reapportionment

lowering the population deviation to 162 but still using

whole counties as the building blocks of districts, and sti1l

creating no majority black district.

Subsequently, by letter of November 30, 1981, the Attorney

General of the United States objected to the constitutional

prohibition against dividing counties finding that the use of

whole counties in apportionment requires the use of large multi-

member districts and that "the use of such mulEi-member dis-

tricts necessarily submerges cognizable minority population

concenEraEions into larger white electorates." On December

7, 1981 and January 20, L982 the Attorney General also

objected to Ehe Senate and House apportionments.

The General Assembly convened in Febru&ry, L982 and

again in April, L982 to reapportion the House and the Senate.

At each session the object was to deviate from the prior

enacted apportionments as littIe as possible while creating

a plan which could muster Section 5 preclearance and which

would be consistent with the one person one vote requirements

of the Equal Protection Clause.

The result of the final apportionment, Chapters one and two

of the Session Laws of the Second Extra Session of L982 is that

some counties covered by Section 5 were divided to form majority

black single-member districts. This was done, however, only to

the extent required by the Attorney General of the United States

pursuant to his authority under Section 5. Some non-covered

-3-

,t

counties were also divided, but only if needed to get population

deviation lower than 158.

In contrast, significant concentrations of black citizens

were left submerged in large majorj-ty white multi-member dj-stricts

consisting of whole (or almost whole) counties not covered by

Section 5, j-ncluding Mecklenburgl Forsyth, Durham, and Wake

Counties. It is undisputed that reasonably compact majority

brack single member House districts courd easily be created by

subdividing each of those counties and that che Coumittees

of the General Assembly had such distrlcts, drawn by a member

of the legislative staff, available to them during the delibera-

tion. Similarly, a majority white single member Senate district

which is reasonably compact could easily be formed by subdividing

Mecklenburg County, and a member of the legislative staff had

done so.

In addition, the legislature created a majority white 4

member district out of wilson, Edgecombe and Nash counties

even though each county is covered by Section5 and a 62.7* black

district coul-d be formed if that distri-ct v/ere subdivided into

single member districts. This area was treated differently

than the other section 5 counties simply because the Attorney

General failed to identify this district by example in his

letter of objection.

Finally, in Eebruary, 1982, on instructj-ons from the Attorney

General to reorganLze the concentrations of black citizens in the

4-

,l

Halifax County, Martin County, Gat-es County area by dividing

a multi-member district and creating a single-member Senate

district, the General Assembly enacted an apportionment j-n

which Senate District #2 had a 51.78 black populati-on. When

the Attorney General objected to this district, the black popu-

lation percentage was increased to 55.18 although the percentage

of black registered voters was sti11 only 46.22. The four

percentage point increase was the minimum thought to be able

to survive the Section 5 preclearance process. At the same time,

District *6, the adjacent district, was left 492 black in popu-

lation, thus fracturing the geographically insular concentration

of black citj-zens in Districts 2 and 6. As a result, neither

district has an effective black voting majority and black voters

have been denied an equal opportunity to elect a representative

of their choi-ce to the Senate.

Thus, in at least seven instances, the House and Senate

submerged significant concentrations of black citj-zens and in

one instance, the Senate fractured the black concentration of

voters as follows:

Percent PercenE Blad<

I$urnber of Black F.:rarple of Possible

C\-rrent District Cor:nty trknbers Population Single }4erber District

Ilouse /136 lbcklerrbr-rg 8 26.52 667. + 717" (2 dlstricts)

Ibuse #39 Forsych(paru) 5 25.L2 70.0

Ilouse #23 Drrhan 3 36.32 70.9

Ilcuse #21 I^iake 6 2I.82 67

Ilcuse #8 Wilson-Edgecornbe-

Nash 4 39.52 62.7

%nate ll22 lbcklenbrrg-

Cabarnrs 4 24.32 70.8

Senate //2 lilcrtheast 1 55.L2 60 .7

Plaintiffs challenge each of these districts.

tr

J

rr. Plaintiffs wilr show that the reappoltionment o

;-

The voting Rights Act applies to craims of discriminatory

redistricting and prohibits redistricting plans that dirute

minority voting strength. congress intended the voting Rights

Act to be a broad charter against arl systems and practices

that diminish black voting strength. when congress extended

the Voting Rights Act in i975, the Senate observed:

As registration and voting of minority citizens

increases, other measures may be resoited to

which dilute increasing minority voting strength.

Such measures may include the adoplion ofdiscriminatory redistricting plans.

S. Rep. No. 94-295,94th Cong., lst Sess. lG-17 (1975).

The senate Report accompanying the 1992 extension and

amendment of tte a.t1/echoes the same concern:

The initial effort to implement the Voting RightsAct focused on registration It is notsurprising, therefore, that to many Americans, theA9t is synonymous with achieving minority registra-tion. _But. registrqtion is @- hurdle

!o g.f f cess.As the Supreme Court s

the Act:

!/ s. Rep. No. 97-417, 97rh cong., 2d sess. (19g2) (hereafter

senate Report). The senate Report is reprinted in ir,e unitedstates code cong. and Ad. News, No. 5, July Lgg2, dt 177 ff.

The first 88 pages are the Report of the committee on theJudiciary and contain the view of the co-sponsors of the

amendments which passed the senate by a vole of g5 to g. l2gcong. Rec. s. 7139 (daily ed. June 18, 19gz). The bill thaLpassed the Senate was subsequently adopted without modificationby the House of Representatives. see note 2, infra. There

bras no need for a conference committee, and noiEwEs ever con-

vened.

6-

The right to vote can be

dilution of voting power

an absolute prohibition

ba1lot. AIlen v. Bd. of

affected by a

as well as by

on casting a

Elections, 398u.s. 544 (1969).

Senate Reportr at 6 (emphasis addded). Accordingly:

[F]or purposes of Section 2, the conclusion

o.. that "there were no inhibitions against

Negroes becoming candidates, and that in fact

Negroes had registered and voted without

hindrance", would not be dispositive. Section

2, as amended, adopts the functional view of

"political process" rather than the

formalistic view ..., [T]his section withoutquestion is aimed at A es

the form of dilution, a t

of the right to register oi to vote.

Senate Reportr Elt 30 n. 120 (emphasis added ) .

Claims of discriminatory redistricting faIl squarely within

the ambit of the Act. rndeed, "[T]he continuing problem with

reapportionment is one of the major concerns of the voting

Rights Act..." Senate Reportr dt 12 n.3.|.

section 2 of the voting Rights Act specificarly prohibits

redistricting plans that result in dilution of minority voting

strength. section 2 reaches any '!system or practices which

operate, designedry or otherwise, to minimize or cancel out the

voting strength and political effectiveness of minority groups."

Senate Reportr dt 28.

A. The Section 2 Standard

On June 29, 1982, the president signed into law an Act

7-

..+

amending Section 2 to provide that voting practices are unlawful

which result

on account of

?/131. Amended Section 2, 42 U.S.C. S 1923, provides:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting or standard, practice, or pro-

cedure shall be imposed or applied by a

State or political subdivision in a manner

which results in a denial or abridgement

of the right of any citizen of the United

States to vote on account of race or color,

or in contravention of the guarantees set

forth in Section 4(t)(2)| as provided in

subsection (b).

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established,

if, based on the totality of the circum-

stances, it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or election

in the state or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by members of a

class of citizens protection by subsection

(a) in that its members have less opportunity

than other members of the electorate to

participate in the political process and to

elect representatives of their choice. The

extent to which members of a protected class

have been elected to office in the State or

political subdivision, is one "circumstance"

which may be considered, provided that

nothing in this section establishes a right

to have members of a protected class elected

in numbers equal to their proportion in the

populat ion.

?/ The House passed its version of a bill amending and extending

the voting Rights Act of 1965 on october 5,1981. 127 cong. Rec.

H. 7011. The Senate thereafter adopted its version of the bill

on June 18, 1982. 128 cong. Rec. s.7139. subsequentryr on June

23, 1982, the House unanimously adopted the final Senate version

of the Act with the understanding that the effect of the Section

2 amendment was identical under either the original House biIl

or the Senate bill . '128 Cong. Rec. H. 3840.

in the denial or abridgement of the right to vote

race or color. Act of June 29, 1982, 96 Stat.

8-

Prior to the 1982 amendment, Section 2 provided in relevant

part as follows (42 U.S.C. S 1923):

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting,or standard, practice, or procedure shalr be imposeaby any State or political subdivision to deny or

abridge the right of any citizen of the United Statesto vote on account of race or color * * * .

rn amending the statute, congress dereted the words,,to deny or

abridge" and substituted new language so that it no$, provides

that no voting procedure, etc., shall be imposed or applied "in

a manner which results in a denial or abridgement,, of the right

to vote on account, of race or color (emphasis addded). congress

also added an entirely ne$, paragraph (designated subsection (b) )

which provides that a vioration of the original paragraph, as

amended (now designated subsection (a)) is established:

if, based on the totality of circumstances, it is

shown that the poriticar processes leading to nomina-tion or election in the State or political subdivisionare not equally open to participation by members of acrass of citizens protected by subsection (a) in thatits members have ress opportunity than other membersof the erectorate to participate in the political

process and to elect representatives of their choice.

congress used the "results" ranguage in the new subsection

(a) in order to eliminate the need to show discriminatory purpose

to estabrish a violation of section ,.2/ The relevant inquiry

is whether a voting practice resurts in an unequar opportunity

1/ See Senate Report, supra, at 16, 17, 27-2g, 31-43i and

1!:-?t.19? (additional views of Senaror Dole); 129 Cong. Rec.s6560 (daily ed., June 9, L9B2) (Kennedy); id. at s677i (daily€d-, June 15, 1982) (spector) i id. at s6g6olaairy ed., June 17,1982) (Dole); id. ar s6647 (daily ed., June io, t-gaz) (Grassl.yiid. at H3840 (June 23, 1982) (Edwards); id. at H3841'(dailv eo.,ilne 23, 1982) (Sensenbrenner) .

9-

a l' t

nto participate * * * and to electr', not whether the inequality

is attributable to a discriminatory nu.no"".1/

congress took the "equarly open to participate', language

from white v. Regester, 412 u.s. 755 (1973), the first case in

which the Supreme Court found a multi-member district system to

be unconstitutional. rn white, the court stated that in

prosecuting a Fourteenth Amendment challenge to a multi-member

district system " It] he plaintiffs t burden is to produce evidence

to support findings that the poritical processes leading to

nomination and election were not equarly open to participation

by the group in question that its members had ress opportunity

than did other residents in the district to participate in the

political processes and to elect legisrators of their choicer,,

412 u.s. at 766. see also whitcomb v. chavis, supra, 403 u.s.

at 149-150.

!/ The effort to amend section 2 began in the House as H.R.3112, 97th cong., lst sess. (1981). as passed in the House, thebill included the subsection (a) "resultin language but objectionswere raised that it did so in sufficientry sweepiig terms tosuggest that a violation of the section could ba eitaUtishedmerery by showing that members of a minority group had not beenelected in numbers equal to the group's proloition in the popula-tion. rn the Senate, compromise-lanluage wls substituted whichincluded the "results" language from th6 House bill, but removedany suggestion that a viotition could be established on the merefailure to obtain proportional representation, and added thetropportunity * * * to participate in the poliiicar process"

language that now appears in iubsection (b). see s-enateReport, EIpLs, at 3-4. This substitute was approved by thesenate after severar days of debate. 129 con|. Rec. ssagT-s6561(daily ed. June 9, 1982)i 3d. ar S6638-5G655 iauily ed., June10, 1982) i id. at s5714-s6726 (dairy €d., June 14, 1g}2i; id. ar

16-77 7-s679sJdaily ed. , June 15, tgbz) i 1d. at s6i14-s69ieI-s6929-s6934, s5938-s6970, si977-s7002 (dar1y ed., June 17,1982)i id. at s7075-s7142 (daity €d., June lg, 1gB2). The Houseaccepted the Senate compromise by voice vote several days later.128 Cong. Rec. H3839-H3846 (daily ed., June 23,19g3).

10

..

)l

As the legislative history in both houses makes clear,

Section 2 was amended primarily in response to the decision of

the Supreme Court in City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55

(1980). See Senate Report at 28; House Report at 29-30. The

amendment of Section 2 was intended by Congress to restore its

original understanding of the standard governing challenges to

discriminatory election practices and procedures which had been

applied by the courts prior to City of Mobile v. Bolden. Both

houses indicated that the statute, when enacted in '1965, did

not require proof of intentional discrimination for a violation,

despite indications to the contrary in the plurality opinion in

City of Mobile v. Bolden, supra, 446 U.S. at 51. See House

Report 292 "The purpose of this amendment to Section 2 is to

restate Congress' earlier intent that violations of the Voting

Rights Act, including Section 2, be established by showing the

discriminatory effect of the challenged practice. " (Footnote

omitted); Senate Report, 17: "The Committee amendment rejecting

a requirement that discriminatory purpose be proved to establish

a violation of Section 2 is fully consistent with the original

legislative understanding of Section 2 when the Act was passed

in 1965." But, of course, regardless of whether Congress was

correct in its understanding of the proof requirement of White

v. Regesterr or any other pre-Bolden voting rights cases, what

is relevant is that Congress enacted a statute which dispensed

with the requirement of proving any kind of discriminatory

1l

purpose to estabrish a voting rights violation. senate Report,

28; House Reportt 2B-9.

Although the results standard of Section 2 derives from

congress' understanding of the standard of proof in white v.

Regester, supra, Congress explicitly provided that the test

for a statutory violation was significantly different from

that under the Constitution.

(a) As previously noted, proof of discriminatory

purpose is not required to estabrish a violation of the

statute, regardress of the standard appricable in constitu-

tional challenges. cf. city of Mobile v. Borden, supra,

446 u.s. at 69, quoting washington v. Davis, 426 u.s. 22g, 240

(1976), that "the invidious quarity of a law craimed to be

racially discriminatory must ultimately be traced to a racially

discriminatory purpose. "

(b) Unresponsiveness in not an element of a statutory

vioration, whatever its relevance in constitutionar cases.

rndeed, congress provided that the use of responsiveness is to

be avoided, because it is a highly subjective factor which

creates inconsistent results in cases presenting similar facts.

senate Report 29, n.1 1 6 ( [T] he amendment rejects the ruling in

Lodge v. Buxton and companion cases that unresponsiveness is a

requisite element. " ) ; House Report 29 , n.94, 30 (,,The proposed

amendment avoids highry subjective factors such as

responsiveness of elected officials to the minority community.,')

rn fact, responsiveness is of no rerevance even in rebuttal, Lf

12

plaintiff chooses not to offer evidence of unresponsiveness.

senate Report at 29, n.116. cf. zimmer v. McKeithen, 495 F.2d

1297 (5th cir. 1973)(en banc) aff'd on other grounds sub nom.

East carroll Parish schor Board v. Marsharr, 424 u.s. G3G

(1977) (per curidrn), referred to in the senate Report as the

"seminal' case. see senate Report at 23. rn zimmerr Do proof was

offered that defendants were particurarly insensitive to the

interests of brack residents, and the absence of a craim of

unresponsiveness did not negate plaintiffs' successful attack on

the at-large elections in East carroll parish. compare Rogers

v. Lodge, _ U.S. _, 102 S.Ct.. 3272 (1982) wherein the

Supreme Court expressly disapproved of the lower court's holding

that proof of unresponsiveness was an essential erement of

a constitutional challenge. see also NAACp v. Gadsden Countv

schoor Board, 691 F.2d 978, 983 (1lth cir. 1gB2) (unresponsive-

ness is not relevant to the question of discriminatory impact).

(c) Foreseeability of consequences is "quite relevant

evidence of a statutory vioration." senate Report 2'l, n.l0g.

For example, evidence that the North Carolina General Assembly

knew that its reapportionment plans submerged concentrations of

minority voters, and knew that a district of. 55t black popura-

tion did not have an effective black voting majority, is

rerevant to praintffs I proof of a statutory vioration.

(d) Whatever limitations may exist on the scope of

the constitutional bar against indirect interference with the

right to vote, see, €.9. r City of Mobile v. Bolden, supra,

13

446 U.S. at 55, n.6 (1980), Section 2 embodies a functional

view of the poritical process and prohibits a very broad range

of impediments to minority participation in the electorate.

Senate Report, 30, n.120i House Report, 30. In particular,

the Congress was concerned about methods of election, such as

at-large elections and the use of murti-member legislative

districts, that tend to

minimize and cancel out minority voting

strength.... Numerous empirical studies

based on data collected from many com-

munities have found a strong Iink between

at-Iarge elections and lack of minority

representation. House Report, 30.

See McMillan v. Escambia County, 588 F.2d 960r 961 n.2 (5th Cir.

1982), reh. den.692 F.2d 758 (Section 2 as amended "encompasses

a broader range of impediments to minorities participating in

the political process than those to which the Bo1den plurality

suggested the original provision was Iimited" ); Buchanan v. The

City of Jackson and the State of Tennessee, No. 81-5333, slip

op. at 9-10 (6th Cir. June 7t 1983).

(e) tack of proportionate representation is relevant

to a claim of vote dilution. Section 2 provides that the

extent to which minorities have been erected to office may be

probative of a violation. The legislative history makes clear

that the Court should considerr ds part of plaintiffsr proof,

an historic pattern of a disproportionately low number of

blacks being elected to the legislative body. House Report at

30:

14

.,.

the fact that members of a racial or lan-

guage minority group have not been elected

in numbers equal to the group's proportion

of the population does not, in itself,

constitute a violation of the section aI-

though such proof, along with objective

factors, would be highly relevant.

Moreover, the sporadic election of a few minority candidates

Senate Report at 29,

v. McKeithen, supra.

.. . the success of black candidates at the

polls ... mightr on occasion, be

attributable to the work of politicians,

who, apprehending that the support of a

black candidate would be politically

expedient, campaign to insure his election.

Or such success might be attributable to

political support motivated by different

considerations namely that election of a

black candidate will thwart successful

challenges to electoral schemes on dilution

grounds. In either situation, a candidate

could be elected despite the relative

political backwardness of black residents in

the electoral district. 485 F.2d at 1307.

Thus, the statute incorporates prior case Iaw that plaintiffs

may prove dirution of brack voting strength despite the fact

that some brack candidates enjoy nominar success at the pol1s.

See, White v. Regester, 412 U.S. at 766i NAACP v. Gadsden

does not vitiate plaintiffs' proof.

n.115, citing with approval Zimmer

County Schoo1 Board, supra, 691 F.2d at 983; Kirksey v.

of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139, 143 (5th Cir.'1977).

Board

B. Elements of Proof Under Section 2

The legislative history provides that

Section 2 violation plaintiffs can show a

to establish a

variety of factors,

15

including those derived from

the Supreme Court in White v.

in subsequent decisions such

as follows:

the analytical framework used

Regester, and as articulated

by

as Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra,

(l)

nation in

extent of any history of official discrimi-

state or political subdivision that touched

the rights of the members of the minority group to register,

to voter oE otherwise to participate in the democratic

process i

(2) The extent to which voting in the erections of

the state or political subdivision is racialry polari zedi

(3) The extent to which the state or political sub-

division has used unusuarly rarge erection districts,

majority vote requirements, anti-singre shot provisions,

or other voting practices or procedures that may enhance

the opportuntiy for discrimination against a minority group;

(4) rf there is a candidate slating process, whether

the members of the minority group have access to that pro-

cess;

(5) The extent to which members of the minority group

in the state or political subdivision bear the effects of

discrimination in such areas as education, employment and

hearth, which hinder their ability to participate effec-

tively in the political processi

(6) whether politicar campaigns have been character-

ized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

The

the

16

(7) The extent to which members of the minority group

have been elected to public office in the jurisdiction.

Senate Report, 28-9. These factors are the most important ones in

evaluating whether or not black voters "have less opportunity than

other members of the electorate to participate in the political

process, and to elect representatives of their choic€r,, within the

meaning of Section 2.

There is no requirement under the statute that any particular

number or aggregate of factors, however, be proved or that they

point one way or the other. "The eourts ordinarily have not used

these factors, nor does the committee intend them to be usedr dS a

mechanical rpoint countingr device." senate Report, 29, n. l1g.

Instead, aPPlication of Section 2 requires the trial courtrs over-

all judgment, based on a totality of the relevant facts and circum-

stances of the particurar case, whether minority voters enjoy

the same opportunity as white voters to participate in the

political process and whether minority voters have an opportunity

equal to that of white voters to elect representatives of their

choice.

fn amending Section 2, Congress thus intended to establish a

reliabre and objective standard for adjudicating voting rights

violations. ft indicated that in determining an overall'rresult'l

of discrimination, based on the totarity of circumstances,

certain types of objective, verifiabre evidence should be

emphasized (such as an officiar history of discrimination in

voting, raciar bloc voting, use of a majority vote requirement

17

, t)

or other practices, such as multi-member legislative districts,

known to enhance the opportunity for discrimination, the extent

of election of minority candidates over an extended period of

time and the present effects of discrimination in such areas as

education, employment and hearth). other types of subjective

and impressionistic evidence were not regarded as relevant or

weighty (such as unresponsiveness), and no inference of discrimi-

natory purpose -- no matter how circumstantiar is required.

Recent cases applying the analysis of amended section 2 to

strike down at-large erections and other dilutive procedures

include Jones v. Lubbock, C.A. No. 5-76-34 (N.D. Tex., Jan. 20,

1983), slip op., 14 ("under the findings of the court with

respect to the factors which the congress deemed to have been

relevant to the determination of this question, and under the

toEality of all of the circumstances and evidence in this case,

it is inescapable that the at-large system in Lubbock abridges

and dilutes minoritiesr opportunities to elect members of their

ogrn choice.') i Thomasville Branch of NAACp v. Thomas county,

Georgia, Civ. No.75-34-THoM (M.D. Ga. Jan.26,1993); Rvbicki

v. The state Board of Erections of the state of rlrinois, et

Err. , No. 81-c-6030 (N.D. rrr. Jan . 20, 1983 ) ; Taylor v. Haywood

County, Tenn., 544 F. Supp. 1122, 1134-35 (W.O. Tenn. 1gg2)

(applying the section 2 factors and granting a preriminary

injunction against use of at-rarge voting for the Haywood

County Highway Commissioners) .

't8

t

C. Plaintiffs I Proof

Plaintiffs intend to prove that the challenged legisla-

tive reapportionment of the North Carolina General Assembly has,

under the totality of circumstances in this case, a racially

discriminatory result in violation of Section 2. By presenting

evidence consistent with the factors identified in the

Senate Report, plaintiffs will show that the use by the North

Carolina General Assembly of multi-member legislative districts

in metropolitan areas with large concentrations of black voters

unlawfully dilutes the voting strength of those voters.

(a) Plaintiffs will show that there has been a long

history of official discrimination against blacks in North

Carolina involving registration and voting including the use of

pol1 taxes, a numbered seat provision and literacy tests.

Plaintiffsr evidence will show that the historic disfranchise-

ment of black voters has continued to inhibit black people from

re-entering the political process, and that past barriers have

a lingering discriminatory impact on participation by black

voters.

The existence of an extensive history of racial discrimina-

tion has always been considered relevant to a claim of unlawful

vote dilution. The courts have recognized the lasting impact of

historic policies of racial discrimination, and have, in fact,

placed the burden on defendants to show that the residual effects

of past patterns have been dissipated. See e.9., Kirksey v.

19

Board of Supervisors of Hinds County, supra at 146; Zimmer v.

McKeithen, supra, at 1305; White v. Regester, supra at 766i

Rogers v. Lodge, 73 L.Ed.2d at 1017, 1024.

(b) Plaintiffs will show that voting in North Carolina is

racially polarized. Plaintiffst evidence wiIl further show

that on the basis of a computer assisted analysis of all

legislative races in the past six years in which a black

candidate ran from a multi-member district at issue in this

'1/case, the polarization on the basis of race hras pervasive.

(c) The parties have stipulated that the State of North

Carolina employs a majority vote requirement in primary elections.

The evidence will show that this 1aw was enacted in the same

legislative session where the General Assembly enacted a statute

permitting 1ocal political parties to conduct all-white primaries,

and that it is well known that a majority vote run-off require-

ment enhances the opportunity for discrimination against minority

9-/voters.

1/ The courts have recognized that in a racially polarized

electorate, there tends to be submergence and dilution of the

voting strength of the minority voters, especially where thejurisdiction uses multi-member or at-large election districts and

a majority vote run-off requirement. See, e.g., City of Port

Arthur v. United States, 74 L.Ed.2d 334, 342 (1982)i United

J6ffiE- orgaffiarey, 430 U.S. 144, 16G-67 (1gTTl:

"Where it occurs, voting for or against a candidate

because of his race is an unfortunate practice.

But it is not rare; and in any district where it

regularly happens, it is unlikely that any can-

didate will be elected who is a member of the

race that is in the minority in that district. "

9_/*e_, e.9., Rogers v. Lodge, 73 L.Ed.2d at 1023, 1024i Citv

of Port Arthur v. United States, 103 S.Ct. 530 at 535; White

". McKeithen, 48S f .ZE'-

at 1 306.

20

The parties have stipulated Ehat North carolina has pre-

viously used a nurnbered seat system for legislative races and an

anti-single shot voting Iaw in many county and municipal elections.

These practices continued until declared unconstitutional by the

federal courts. These practices are identified in the Senate and

House Reports as enhancing the opportunity for discrimination

against black voters. Senate Report at 29i House Report at 18.

Plaintiffs will produce evidence that other practices sti11 in use

by the State of North Carolina also enhance the opportunity for

discrimination. Such practices include the use of election

districts that are unusually large and the use of multi-member

Iegislative districts. The large size of some of the multi-

member districts makes it particularly difficult for blacks to

campaign effectively because of the increased costs of running

for office. Senate Report at 29i see Rogers v. Lodge, supra,

102 S.Ct. at 3280-81 ("The court concluded, as a matter of law,

that the size of the county tends to impair the access of blacks

to the political process.") See Connor v. Johnson, 402 U.S.

690, 692 (1971) (preference for single member districts in

"Iarge" districts); House Report at 18: "The Committee heard

numerous examples of how at-large elections are one of the

most effective methods of diluting minority strength in the

covered jurisdictions".

(d) Plaintiffs do not contend that there is a formal

candidate slating process in North carorina. plaintiffs wirl

show that in certain parts of North Carolina there is an informal

slating process in which members of the minority group do not

part i cipate .

21

(e) The evidence wirr show that members of the

minority group stirl bear the effects of discrimination in

education, employment and health and therefore their ability to

participate in the poriticar process is hindered .Z/ *u.n of

the data showing a disparity in income, educational achievement,

health and housing is stipulated.

(f) The evidence wirl show the historic use of

raciar appears in erectoral campaigns starting in lggg and

the continuing and persistent use of raciar telegraphing in

election campaigns from 1976-1993.

(g) The evidence will show that blacks have not been

elected to pubric office in the state of North carorina in

numbers even approaching their proportion of the popuration.

Praintiffs wish to make it crear that we do not contend that

blacks have a right to proportional representation in the North

Carolina General Assembly or that evidence of under representation

is conclusive proof of a section 2 violation. we wirl simply

show, consistent with the statute and legislative history, that

there is stitl under-representation of bracks in the state

legislature, and that this has been true throughout this century.

For exampler prior to 1969r rro black was eledted to either the

1( Plaintiffs are not required to show a causal nexus betweentheir disproportionate edudational 1eve1, income leveI and livingconditions and their depressed rever of participation in thepolitical process. senlte Report at 2g, cilin!-wt,ite

". Regester,412 u-s- at 768; Kirksev v. soaro or supervisois;=ga F.2aE--145:

"Inequality of access is an inference

existence of economic and educational

22

which flows from the

inequal it ies. "

state senate or state House. since 1969, although bracks con-

stitute more than 25* of the popuration of the charlenged

districts, onry 20 out of 320 legislators in the Generar

Assembry elected from those districts have been brack. see

Stipulation of Parties, numbers 95 and 96.

(h) Evidence of the tenuousness of the policy

underlying the state's use of large multi-member districts has

probative value as part of plaintiffs' evidence. senate

Report, 29. The tenuousness of the staters policy is not,

however, identified in the regisrative history as a typical

factor nor even particularly important to establish a violation.

rn this case, dlthough our proof does not depend on it, prain-

tiffs are prepared to present evidence, in anticipation of the

defendantsr case, that the policy underrying the staters use of

large murti-member districts and not dividing counties is, in

fact, tenuous. For exampre, praintiffs are prepared to show

that the legislature ignored its own previously adopted criteria

for reapportionment, relied on outdated considerations regarding

the nature of business conducted by the legislature and the

legitimate needs of county government, and allowed the protec-

tion of white incumbents and an anti-Repubri'can animus to

dominate the process. Plaintiffs contend that where political

considerations are allowed to dominate neutral redistricting

objectives and constitutional imperatives, a,,politically

balanced" plan that nevertheless consciously minimizes minority

voting strength cannot be sustained. see e.g., perkins v. city

23

. rD./}

of West Helena, Ark., 675 F.2d 201, 216-17 (Bth Cir. 19g2li

Robinson v. commissioners court, 505 F.2d 674 (5th cir. 1974).

Plaintiffs further contend that the fairure to divide

counties is not excused by the North carolina constitution.

Plaintiffs will present evidence that according to the record

of the legislative proceedings, the Generar Assembry did not

consider the North Carolina Constitutionts provisions binding

on it after the united states Attorney Generar interposed a

section 5 objection. Finalry, even if the Generar Assembly had

relied on the provision of the North Carolina Constitution, the

supremacy clause of the United States Constitution, Article VI,

section 2t requires that section 2 of the voting Rights Act

supersede the provisions of state 1aw.

The above discussion of plaintiffs' proof focuses on show-

ing how the challenged plans resurt in dilution of minority

voting strength through the use of multi-member districts. rn

addition, plaintiffs wilI show that the challenged reapportion-

ment prans result in dilution of minority voting strength by

fracturing concentrations of brack voters. Fracturing is a

classic device for diluting the voting strength of a geographi-

cally cohesive brack community. "The most crucial and precise

instrument of the denial of the black minority's equal access

to poritical participation, however, remains the gerrymander of

precinct lines so as to fragment what could otherwise be a co-

hesive voting broc. " Kirksey v Board of supervisors of Hinds

county, supra, 554 F.2d at 149. plaintiffs wirr show that in

24

senate District 2, the Generar Assembry fractured the voting

strength of black voters, and that under the totality of

circumstances, this resurted in a violation of section 2.

The defendants appear to take the view that simply because

blacks can register and vote in North Carolina, and have

recently been elected to a few offices in the state, there can

be no dilution of minority voting strength. consequently, they

virtually ignore the rich evidence plaintiffs wilr present of

racial bloc voting, of subtre racial appears in elections, the

depressed socio-economic status of blacksr and the continuing

effects of past discrimination and the other factors indicated

by Congress which show that an election practice results in the

denial or abridgment of the equal right to vote. This limited

view has no basis in the Iaw, the legislative history or prior

cases. Congress specifically rejected the view urged by

defendants when it amended and extended the Voting Rights Act

in 1982. Senate Report, 30, n.120.

The discriminatory resurtsr test focuses on whether the

poriticar processr ds it has worked, and as it no$/ promises

to work, has made it equally possible for minority voters to

participate in the political process and elect representatives of

their choice to office. The factors listed in the legislative

history as probative of this inquiry, which plaintiffs will

prove at triaI, demonstrate that the 1981 and 1982 legislative

reapportionments of the North Carolina General Assembly result in

the denial and abridgment of the right of blacks to vote on

25

a r+

account of race in violation of

Act.

Section 2 of the Voting Rigths

III. Plaintiffs will show that the 1981 and 1982 1 i s lat ive

reapport ionments of the North Caro ina Genera Assemb

ntentiona scr minate a ainst ack voters

n the state

Although not necessary to plaintiffs' claims under Section

2 of the Voting Rights Act, evidence that defendantrs redistrict-

ing plan purposefully dilutes the voting strength of blacks

supports those claims. As explained in the Report of the

Senate Committee on the Judiciary, dt 27 z

The amendment to the language of Section 2 is designed

to make clear that plaintiffs need not provide a

discriminatory purpose in the adoption or maintenance

of the challenged system or practice in order to

establish a violation. Plaintiffs must either prove

such intent t ot, alternatively, must show that the

challenged system or practice, in the context of all

the circumstances in the jurisdiction in question,

results in minorities being denied equal access to the

political process.

Evidence that the redistricting plan was motivated, under

the totality of circumstances, by an intention to minimize or

dilute black voting strength is also an element of plaintiffsr

claims under the Fourteenth Amendment. Rogers v. Lodge, 102

s.cr. 3272, 3275-76 (1982).

The Supreme Court has articulated two principles to guide

the lower courts in determining the existence of discriminatory

purpose. The first principle is that the plaintiffs need not

prove that the challenged redistricting plan was motivated

solely by a discriminatory purpose. Once it has been shown

that discriminatory considerations v,,ere one factor, plaintiffs

26

..|

have established their prima facie case. The burden then

shifts to the defendants to establish that precisery the same

district boundaries would have been drawn even in the absence

of discriminatory considerations. vilrage of Arlington

Heights v. Metroporitan Housing Deveropment corp., 429 u.s.

252t 265-55, 270-71 n.21 (1977). According to the court in

Rybicki v. State Board of Elections, No. g1 c. 6030 at 57-62

(N.D. I11. Jan. 12r 1982)t the burden this places on the

defendant is a very heavy one.

The second principle is that discriminatory intent can be

proven by circumstantial evidence:

[D] iscriminatory intent need not be proven by

direct evidence. ',Necessarily, an invidious

discriminatory purpose may often be inferred from

the totality of the relevant facts, including the

fact, if it is true, that the law bears more

heavily on one race than another.,'

Rogers v. Lodge, supra at 3275 (1982), quoting Washington

v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 242 (1976). fn Rogers, the Supreme

court rejected the prurality's suggestion in Mobire that

plaintiffs must prove through direct evidence that a dis-

criminatory intent was the motivating factor of the decision-

makers. Buchanan v. The city of Jackson, et ar., No. 51-5333,

5th cir. (June 7, 1983) slip opinion at 6t 8. copy attached.

This principre has been squarely accepted by the congress

as exprained in the legislative history to the 1982 section 2

amendments:

Plaintiff may establish discriminatory intent for

purposes of this Section [Section 2], through

27

r.l

direct or indirect circumstantiar evidence,including the normal inferences to be drawn fromthe foreseeability of defendant's actions which

"is one type of quite relevant evidence of ra_cially discriminatory purpose.,, Dayton Bd.of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 u.s. 526-36-n.g (1g7g).

senate Reportr €lt 27 n.108. consequentry, discerning dis-

criminatory purpose "demands a sensitive inquiry into such

circumstantial and direct evidence of intent as may be avair-

able.n Arlington Heights, supra 429 U.S. at 266.

The Fifth circuit recently summarized the evidentiary

sources alluded to in Arlington Heights which are useful for

assessing the existence of purposeful discrimination as

follows:

( 1 ) the historical background of the action,particularly if a series of actions have

been taken for invidious purposes i (2) thespecific sequence of events leading up tothe challenged action; (3) any procedural

departures from the normal procedural

sequence i (4 ) any substantive departure from

normal procedure, i.e., whether iactors

normally considered important by the

decision-maker strongly favor a-decision

contrary to the one reached; and (5) thelegislative history, especially where

contemporary statements by members of the

decisionmaking body exist.

McMillan v. Escambia countv,639 F.2d 1239r 1243 (5th cir. lggl)

Defendantsr course of conduct during the redistricting

process strongly supports the inference that the legislature

fractured the black population in Northeastern Senate District

2 and minimized their voting strength intentionally. The

defendants enacted the redistricting plan in a manner calculated

28

r.-

to minimize the input of the black community. The Supreme

Court has recognized that evidence of purposeful discrimination

can be found in "the specific sequence of events leading up to

the challenged decision." Arlington Heights, supra, 429 U.S.

at 267.

Plaintiffs will present other evidence of the discriminatory

purpose behind the creation of Senate District 2. Plaintiffs

will show that the General Assembly drew a 558 black district,

knowing that black voters will be unable to elect representa-

tives of their choice from a district that is significantly less

8l

than 657" bLack.-

Plaint,iffs will show that by drawing a 55t black district

in Senate District 2, the General Assembly fractured a concen-

tration of black voters in order to minimize their voting

strength. Courts have found evidence of fracturing to be

probative of racial purpose. As the three judge court in D.C.

concluded in Busbee v. Smith, 549 F. Supp. 494r 517 (D.D.C. 1982),

aff I d. u. s. , 103 s.cr. 809 (1983):

9_/ The 65t figure is a general guideline which has been used

by the Department of Justice, reapportionment experts and the

courts as a measure of the minority population in a district

needed for minority voters to have a meaningful opportunity to

elect a candidate of their choice. See Mississippi v. United

States, 490 F. Supp. 569 (D.D.c. 197ET; ffi,?[-J--U.S.-70-m-

af98-0T. The 65t guideline, which the suprenre Court char-

acterized as "reasonable" in United Jewish Organization Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U. S. 1 44, 164 ( 1 977 e younger

median population age and the lower voter registration and

turnout of minority citizens. Plaintiffs will show that the

General Assembly was aware of the significance of this 65t

f igure.

29

{ra

fn this case, the state fragmented the large and

contiguous black population that exists in the

metropolitan area of Atlanta by splitting that

population between two Congressional districts, thus

minimizLng the possibility of electing a black to

Congress in the Fifth Congressional District. The

impact of this state action is probative of racial

purpose.

A discriminatory purpose such as to render the challenged

prans invalid may be inferred from the totarity of relevant

facts, incruding a history of raciar discrimination, a racially

polarized erectorate, the use of a majority vote requirement,

the deviation from substantive reapportionment criteria and the

submergence and fracturing of concentrations of black voters

with a disproportionately adverse impact on members of the

minority voting community. Rogers v. Lodge, supra, 73 L.Ed.2d

at 1017, 1024; Busbee v. smith, supra. see state of Mississippi

v. U.S., 490 F. Supp. 569 (D.D.C. 1979) aff rd. 444 U.S. 1050

(1980); City of Port Arthur Texas v. United States, Civil

Action No. 80-0648, at 58 (D.D.C. June 12, 1981 ), af f rd

U. S. , 103 S.Cr. 530 (1982).

CONCLUSION

fn the seminal case of Zimmer v. [icKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297

( 5th Cir. 1973) | Judge Gewin recalled

follows:

If liberty and equality, as is thought by

somer €rE€ chiefly to be founded in democracy,

they wilI be best attained when all persons

alike share in the government to the utmost.

Politics, Book II,

cited at 485 F.2d at 1300.

30

t,he words of Aristotle as

t,l

As with the Zimmer case, this Court is being called upon

to consider the extent to which the Constitution of the United

States and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 compel adherence to

the principle of "all persons alike" sharing in government "to

the utmost.'r As a consequence of the 1982 amendments to the

Voting Rights Act the task of this Court has been made easier.

In Section 2t there is now a clear basis for enjoining any

election practices or procedures that "are not equally open to

participation" by black voters. Plaintiffs will prove at trial

that under the challenged 1981 and 1982 reapportionment of the

North Carolina General Assembly, they have "less opportunity

than other members of the electorate to participate in the

political process and to elect representatives of their choice."

Plaintiffs contend that the 1981 and 1982 legislative

reapportionments of the North Carolina General Assembly should

be enjoined because they have a discriminatory result in

violation of Section 2. Plaintiffs will also show that the

challenged plans were enacted with a discriminatory purpose

in violation of Section 2 and the United States Constitution.

31

!r -

Dated: Jul-y Lo, 1983

Respectf u1ly submitted,

J. LeVONNE

LESLIE J. WINNER

Chambers, Eerguson, Watt,

Wallas, Adkins & Fuller, p.A.

Suite 730 East Independence plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

7041 37s-9461

,-- i,,,'U, )lll "

1t''Qzttt l -'-l'^u,n .^ 9.-a,

--

JACK GREENBERG

LANI GUINIER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circ1e

New York, New York 10019

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

1v"tu

32

r-.' +

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned hereby certifies that she has

served copies of the foregoing PRE-TRIAL MEMOMNDIIM

opposing counsel by hand-delivering copies of same

JAI"IES WALLACE , JR. and ROBERT N . HIINTER, JR.

This Al aay of July, 1983.

A/n l,

Attorney

this day

upon

to