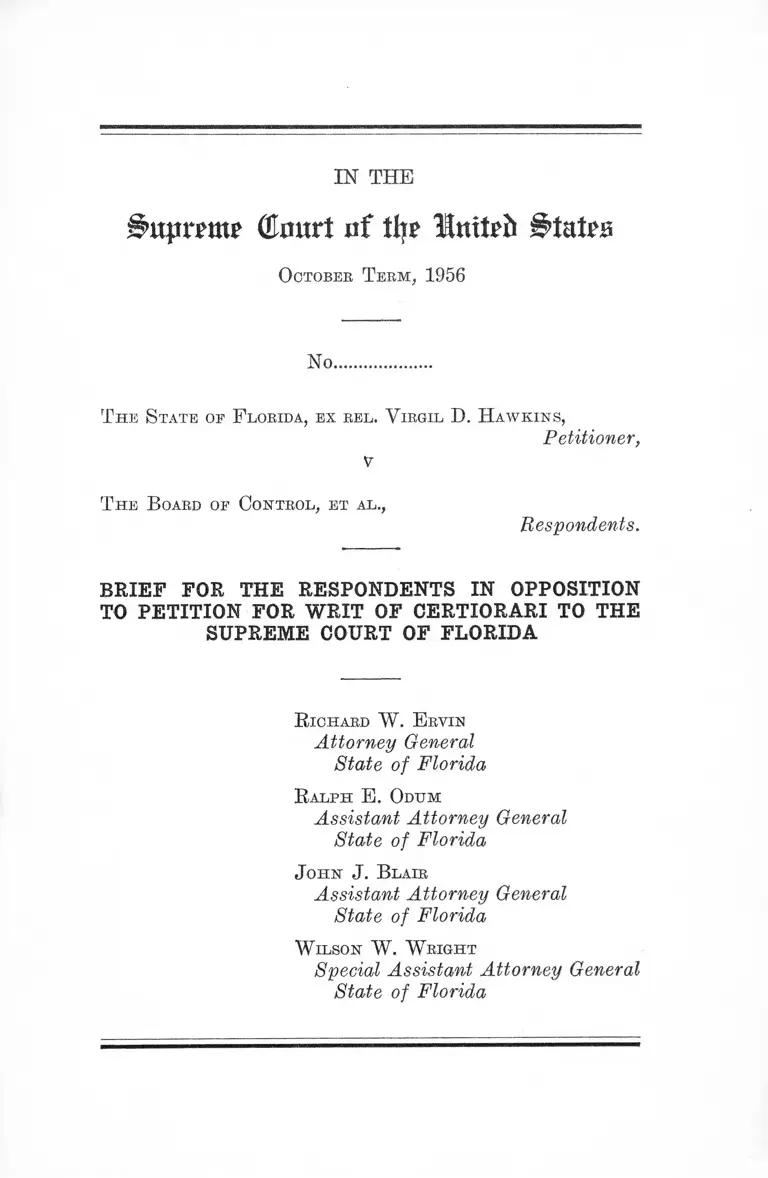

Florida v. Board of Control Brief for the Respondents in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Florida

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Florida v. Board of Control Brief for the Respondents in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Florida, 1957. 549382fd-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3624c35d-85f5-43fe-aa5f-3152d36bb33a/florida-v-board-of-control-brief-for-the-respondents-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-florida. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

g>uprrmp ( ta r t uf tl)p Inttrb States

O c to b er T e r m , 1956

No.

T h e S ta te ox? F lo r id a , e x e e l . V ir g il D . H a w k in s ,

Petitioner,

V

T h e B oard o f C o n t r o l , e t a l .,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

R ic h a r d W . E r v in

Attorney General

State of Florida

R a l p h E . O d u m

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

J o h n J . B l a ir

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

W il s o n W . W r ig h t

Special Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

IN THE

^uprpmp GLxmtt of tty? Inttefe States

O c to b er T e r m , 1956

No,

T h e S t a t e oe F lo r id a , e x r e l . V ir g il D . H a w k in s ,

Petitioner,

V

T h e B oard o f C o n t r o l , e t a l .,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

R ic h a r d W . E r v in

Attorney General

State of Florida

R a l p h E . O d u m

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

J o h n J, B l a ir

Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

W il s o n W . W r ig h t

Special Assistant Attorney General

State of Florida

INDEX

Opinions Below _______________________________________________ X

Jurisdiction ______

Questions Presented

Statement _______

Argument _____________________________________________________ 24

Part One: The Law ________________________________________ 14

Part Two: Factual Considerations ___________________________ 28

Conclusion ___________________________________________________ 5g

Appendix A

Opinion of U. S. Supreme Court of March 12, 1956, in The State of

Florida, ex rel. Virgil D. Hawkins v. The Board of Control, et al. __ 60

Appendix B

House Concurrent Resolution No. 174 (Florida) _________________ 61

Appendix C

Report of the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee__________ 69

CITATIONS

Cases:

Alexander v. Hillman, 296 U. S. 222, 56 S. Ct. 204, 80 L. ed 192 18

Bowman v. Wathen, 1 How. 189, 11 L. ed 97__________________ 16

Bradenton v. State, 118 Fla. 838, 160 So. 506, 100 A.L.R. 400____ 17

Bruce v. Tobin, 38 S. Ct. 7, 245 U.S. 18, 62 L. ed 1 2 3 __________ 19

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, 98 L. ed

873, 74 S. Ct. 686, 38 A.L.R. 2d 1180; and 349 U.S. 294, 75 S. Ct.

753, 99 L. ed 1083 _____________________________________1; 14) 17

Brown v. Dewell, 131 Fla. 566, 179 So. 695, 115 A.L.R. 857_____1 ’ 15

Burgess v. Seligman, 107 U.S. 20, 2 S. Ct. 10, 27 L. ed 359 ______ 26

Bute v. People of State of III, 68 S. Ct. 763, 333 U.S. 640, 92

L. ed 986 ------------------------------------------------------------------------- 25, 26

City of Safety Harbor v. State ex rel. Smith, 136 Fla. 636, 187 So.

173 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 15

Eccles v. Peoples Bank, 333 U.S. 426, 68 S. Ct. 641, 92 L. ed 784 18

Feldman v. United States, 64 S. Ct. 1082, 322 U.S. 487, 88 L, ed

1408, 154 A.L.R. 982_______________________________________ 25

Fox Film Corp. v. Muller, 55 S. Ct. 444, 294 U.S. 696, 79 L. ed

1234, certiorari dismissed, 56 S. Ct. 183, 296 U.S. 207, 80 L.

ed 1 5 8 ___________________________________________________ ig

Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 206 U.S. 230, 27 S. Ct. 618,

51 L. ed 1038 _____________________________________________ 18

Holliday v. Pacific Atlantic S.S. Co., D.C. Del. 1953, 117 F. Supp.

729, affirmed 212 F. 2d 206 ________________________________ 16

Hoxie v. N. Y., 73 A. 754, 82 Conn. 352 ______________________ 23

In re Briley’s Estate, 155 Fla. 798, 21 So. 2d 595 ______________ 25, 26

In re Morris, Ala., 9 Wall. 605, 19 L. ed 799 __________________ 16

In re Opinion of the Justices, 8 N.E. 2d 753, 297 Mass. 567 _______ 25

Page

I

to

b

o

to

Page

Konkel v. State, 170 N.W. 715, 168 Wis. 335 ______________ __ 23

Magwire v. Tyler, 17 Wall. 253, 21 L. ed 576 __________________ 19, 20

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304, 4 L. ed 97 __________19, 20

Mayo v. Polk County, 169 So. 41, affirmed 81 Law ed 376 ______ 44

Miami v. Huttoe, 40 So. 2d 899 _____ _______________________ 17

Morton Salt Co. v. Suppiger Co., 314 U.S. 488, 62 S. Ct. 402, 86

L. ed 363 ______________________________________ ______........ 16

McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316, 4 L. ed 579 ________ 19, 20, 24

Naim v. Naim 197 Va. 734, 90 S.E. 2d 849; 350 U.S. 985, 76 S.

Ct. 472, 100 L. ed 852 ________________ __________ ___ ____ ___ 14

Nelson v. Lindsey, 151 Fla. 596, 10 So. 2d 131 ______ _________ 17

New Jersey v. New York, 283 U.S. 473, 51 S. Ct. 519, 75 L. ed

1176 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- --- 18

Parker v. Broom, 63 S. Ct. 307, 317 U.S. 341, 87 L. ed 315 ....... 23

Penn v. Tollison, 26 Ark. 545, 577 _________________ _________ 26

People v. Daly, 105 N.E. 1048, 212 N. Y. 183 ................................... 23

People of the State of New York v. State of New Jersey and Passaic

Valley Sewerage Commissioners, 256 U.S. 296, 41 S. Ct. 492, 65

L. ed 937 ______________________________________ __________ 18

Ryan v. State, 58 S. Ct. 233, 302 U. S. 186, 82 L. ed 187________ 23

Safety Harbor v. State, 136 Fla. 636, 187 So. 1 7 3 _____________ 17

Somlyo v. Schott, 45 So. 2d 502 ______________________ _____ 15

So. Fork Canal Co. v. Gordon, C. C. Cal. 1868, Fed case #13,189,

2 U.S. 479, 8 A.L.R. 279 ____________________________________ 16

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1, 31 S. Ct. 502, 55

L. ed 619 ________________________________________________ 18

Stanley v. Schwalby, 162 U.S. 255, 40 L. ed 960, 16 S. Ct. 754 ____19, 20

State ex rel American Legion 1941 Convention Corporation of Mil

waukee v. Smith, 293 N.W. 161, 235 Wise. 443 _______________ 25

State ex rel Bottome v. City of St. Petersburg, 126 Fla. 233, 170

So. 730 __________________________________________________ 15

State ex rel. Carson v. Bateman, 131 Fla. 625, 180 So. 2 2 ________ 15

State v. Daytona Beach, 129 Fla. 896, 176 So. 847 _____________ 17

State ex rel Gibbs v. Gordon, 138 Fla. 312, 189 So. 437 ________ 25

State ex rel Gibson v. City of Lakeland, 126 Fla. 342, 171 So.

227 ______________________________________________________ 15

State of Florida, ex rel. Virgil D. Hawkins v. Board of Control of

Florida, et al, 47 So. 2d 608 (1950), 53 So, 2d 116 (1951), 60 So.

2d 162 (1952), 83 So. 2d 20 (1955), 93 So. 2d 354 (1957). 342,

U.S. 877, 72 S. Ct. 166, 96 L. ed 659; 347 U.S. 971, 74 S. Ct.

783, 98 L. ed 1112; 350 U.S. 413, 76 S. Ct. 464, 100 L. ed 486;

reh. den. 351 U.S. 915, 76 S. Ct. 693, 100 L. ed 1449 ____1, 2, 3, 10, 28

State ex rel Long v. Carey, 121 Fla. 515, 164 So. 1 9 9___ 15

State v. Miami, 153 Fla. 90, 13 So. 2d 707 _________ 17

State ex rel Norman v. Holmer, 160 Fla. 434, 35 So. 2d 396 ____ 15

State v. West Palm Beach, 141 Fla. 244, 193 So. 297 ___ 17

State ex rel West Flagler Kennel Club v. Florida State Racing Com

mission, 74 So. 2d 691 ____________________________________ 15

Thornhill v. Kirkman, 62 So. 2d 740 _________________ _______ 44

II

Page

Touchton v. Fort Pierce, 109 F. 2d 3 7 0 ______________________ 17

United Automobile, Aircraft and Agricultural Implement Workers,

et al v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, et al., 351 U.S.

266, 76 S. Ct. 794, 100 L. ed 1162__________________________ 21

United Enterprises v. Dubey, 128 Fed. 2d 843, 87 L. ed 537 ___ 45

United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U.S. 106, 31 S. Ct.

632, 55 L. ed 663 ___________ _______________________________ 18

United States v. Morgan, 307 U.S. 183, 59 S. Ct. 795, 83 L. ed

1211______________________________________________________ 17

Urie v. Thompson, 69 S. Ct. 1018, 337 U.S. 163, 93 L. ed 1282 19

Westfall v. United States, 47 S. Ct. 629, 274 U.S. 256, 71 L. ed

1036 _______________________________________________________ 25

Williams v. Bruffy, 102 U.S. 248, 26 L. ed 135________________19, 20

Statutes:

United States Code, Title 28 _______________________________ 19

United States Code, Sections 1257(3), 1651(a) and 2106 of

Title 28 _________________________________________________ 2

Miscellaneous:

Congressional Record for 1956, Vol. 102, No. 54, p. 5092 ________ 38

Farewell Address of George Washington _________ _____ _ 24

Federalist P apers_____________________________ 23

First Inaugural Address, Thomas Jefferson _______________________ 23

Injunctions and Other Extraordinary Remedies, Section Edition, by

T. C. Spelling _____________________________________________ 15

Martin, John Bartlow, “The Deep South Says Never,” Saturday

Evening Post of June 15, 1957 _______________________________ 33

Myrdal, Gunnar, “An American Dilemma,” pages 58, 61 ________ 30

III

j^uprottr ( ta r t of tfyr InitrtJ Stairs

O c to b er T e e m , 1956

IN THE

No.

T h e S t a t e oe F lo r id a , e x e e l . V ir g il D. H a w k in s ,

Petitioner,

v.

T h e B oard oe C o n t r o l , e t a l .,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinions of the United States Supreme Court are

reported as follows: State of Florida, ex rel. Virgil D.

Hawkins v. Board of Control of Florida, et al, 342 U.S.

877, 72 S.Ct. 166, 96 L.ed. 659; 347 U.S. 971, 74 S.Ct. 783

98 L.ed. 1112; 350 U.S. 413, 76 S.Ct. 464, 100 L.ed. 486';

reh. den. 351 U.S. 915, 76 S.Ct. 693,100 L.ed. 1449, Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, 98 L.ed. 873,

74 S.Ct. 686, 38 A.L.R. 2d 1180; and 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct.

753, 99 L.ed. 1083. The opinions of the Florida Supreme

Court are reported as follows: State ex rel. Hawkins v.

Board of Control of Florida, et al, 47 So. 2d 608 (1950),

53 So. 2d 116 (1951), 60 So. 2d 162 (1952), 83 So. 2d 20

(1955), 93 So. 2d 354 (1957).

1

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked under Sections

1257(3), 1651(a) and 2106 of Title 28 of the United States

Code.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

May the Supreme Court of Florida in the exercise of

its discretion delay the issuance of its writ of mandamus

ordering petitioner’s admission to the University of Florida

when such court has before it evidence that to order im

mediate admission of petitioner at this time would work

a serious public mischief and would seriously interefere

with the proper operation of the State University System?

Did the Supreme Court of Florida act in violation of the

instructions issued by this Court on March 12, 1956, when,

predicated upon evidence received subsequent to the issu

ance of such instructions to the effect that immediate

admission of petitioner to the University of Florida would

create havoc in the State University System and cause

serious public mischief, said state court withheld the issu

ance of its writ of mandamus pending the disclosure of

evidence by petitioner that serious harm to the state and

school system would not result thereby?

Should this Court refuse to accept the findings and de

cision of the Florida Supreme Court and enter its own

judgment ordering the immediate admission of petitioner

to the University of Florida?

STATEMENT

The history of this case is found in State ex rel. Hawkins

v. Board of Control, et al, (Fla.) 47 So. 2d 608; (Fla.) 53

So. 2d 116, cert, denied 342 U.S. 877, 72 S.Ct. 166, 96 L,ed.

659; (Fla.) 60 So. 2d 162, cert, granted 347 U.S. 971, 74 S.Ct.

783, 98 L.ed. 1112; (Fla.) 83 So. 2d. 20, cert, denied 350 U.S.

413, 76 S.Ct. 464, 100 L.ed. 486, reh. denied 351 U.S. 915, 76

S.Ct. 693, 100 L.ed. 1449; (Fla.) 93 So. 2d 354.

2

On May 30, 1949, petitioner brought mandamus proceed

ings in the Florida Supreme Court against respondents to

compel his admission to the College of Law at the Uni

versity of Florida. The Court, on August 1, 1950, ruled

that similar facilities in the state for Negroes satisfied the

equal protection requirements of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. The Court did not enter a final order but retained

jurisdiction in order to permit the parties to seek further

relief at some later date. (Fla.) 47 So. 2d 608. On May

15, 1951, petitioner filed a motion again in the Florida

Supreme Court for a peremptory writ of mandamus. The

motion was denied on June 15, 1951, on the grounds that

no showing was made for the issuance of the writ. (Fla.)

53 So. 2d 116. Petitioner then filed a petition for writ of

certiorari in the United States Supreme Court. The petition

was denied on the grounds that no final judgment had

been entered. 342 U.S. 877. The petitioner filed his motion

for a peremptory writ of mandamus in the Florida Supreme

Court again, and it was denied August 1, 1952. (Fla.) 60

So. 2d 162. Reapplication was then made by petitioner to

the United States Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari.

On May 24, 1954, the United States Supreme Court re

manded petitioner’s cause to the Florida Supreme Court

with directions that such cause be reconsidered “ in the

light of the segregation cases decided May 17, 1954, Brown

v. Board of Education, etc., and conditions that now prevail

. . . in order that such proceedings may be had in the said

cause in conformity with the judgment and decree of this

(United States Supreme) Court above stated, as, according

to right and justice and the Constitution and Laws of the

United States, or to be had therein . . . ” State ex rel

Hawkins v. Board of Control, 347 U.S. 971, 74 S.C’t. 783,

98 L.ed. 1112.

Pursuant to the mandate of the Supreme Court of the

United States, the Florida Supreme Court, on July 31, 1954,

3

entered an order directing the petitioner to amend his

original petition in mandamus “ so as to place before this

(Florida Supreme) Court the issues raised by the original

petition ‘in the light of the segregation cases decided May

17, 1954, Brown v. Board of Education etc., and conditions

that now prevail,’ ” and directing the respondents “ to

amend their return so as to present to this Court any

answers they may have to said amended petition which

will enable this Court to carry out the mandate of the

Supreme Court of the United States.”

In due course, and prior to the ‘ ‘ implementation decree ’ ’

of the United States Supreme Court, respondent filed an

amended return which, among other defenses, stated “ the

admission of students of the Negro race to the University

of Florida, as well as to other institutions of higher learn

ing established for white students only, presents grave and

serious problems affecting the welfare of all students and

the institutions themselves and will require adjustments

and changes at the institutions of higher learning; and re

spondents cannot satisfactorily make the necessary changes

and adjustments until all questions as to time and manner

of establishing the new order shall have been decided on

further consideration of the United States Supreme Court.”

On October 19, 1955, the Supreme Court of Florida held,

in essence, that although petitioner may not be constitu

tionally denied admission to the University of Florida be

cause of race, nevertheless the possible threat of mischief

and economic havoc to the public and the state university

system, and the attendant possible need for time to assure

a proper and smooth transition to a new order in the State

University System, lent validity tô the above-mentioned

defense of respondents, which was. designed to establish a

predicate for an understanding of such need. The Supreme

Court of Florida therefore determined that at least a need

existed for intelligence in this regard before it could prop

erly issue its peremptory writ of mandamus. The Supreme

4

Court of Florida considered this determination a fortiori

essential and valid in light of this Court’s decision of May

31, 1955, herein referred to as the “ implementation de

cision,” wherein it was stated:

“ Full implementation of these constitutional principles

may require solution of varied local school problems.

School authorities have the primary responsibility of

elucidating, assessing, and solving these problems;

courts will have to consider whether the action of

school authorities constitutes good faith implementa

tion of the governing constitutional principles. Because

of their proximity to local conditions and the possible

need for further hearings, the courts which originally

heard these cases can best perform this judicial ap

praisal. Accordingly, we believe it appropriate to re

mand the cases to those courts.

“ In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the courts

will be guided by equitable principles. Traditionally,

equity has been characterized by a practical flexibility

in shaping its remedies and by a facility for adjusting

and reconciling public and private needs. These eases

call for the exercise of these traditional attributes of

equity power.

“ At stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs in

admission to public schools as soon as practicable on

a non-discriminatory basis. To effectuate this interest

may call for elimination of a variety of obstacles in

making the transition to school systems operated in

accordance with the constitutional principles set forth

in our May 17, 1954, decision. Courts of equity may

properly take into account the public interest in the

elimination of such obstacles in a systematic and effec

tive manner. But it should go without saying that the

vitality of these constitutional principles cannot be

allowed to yield simply because of disagreement with

them.

“ While giving weight to these public and private con

siderations, the courts will require that the defendants

make a prompt and reasonable start toward full com

pliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such a

5

start has been made, the courts may find that addi

tional time is necessary to carry ont the ruling in an

effective manner. The burden rests upon the defendants

to establish that such time is necessary in the public

interest and is consistent with good faith compliance

at the earliest practicable date. To that end, the courts

may consider problems related to administration, aris

ing from the physical condition of the school plant,

the school and transportation system, personnel, re

vision of school districts and attendance areas into

compact units to achieve a system of determining ad

mission to the public schools on a non-racial basis, and

revision of local laws and regulations which may be

necessary in solving the foregoing problems. They will

also consider the adequacy of any plans the defendants

may propose to meet the problems and to effectuate

a transition to a racially non-discriminatory school

system. During this period of transition, the courts

will retain jurisdiction of these cases.

“ The judgments below, except that in the Delaware

case, are accordingly reversed and remanded to the

district courts to take such proceedings and enter such

orders and decrees consistent with this opinion as are

necessary and proper to admit to public schools on a

racially non-discriminatory basis with all deliberate

speed the parties to these cases. . . .

“ It is so ordered.”

The Supreme Court of Florida further indicated that the

clear import of the “ implementation decision” was that

State Courts shall apply equitable principles in the deter

mination of the time when segregated schools shall become

integrated. Borrowing from the language of the ‘ ‘ implemen

tation decision” the Florida Court said: “ these cases call

for the exercise by the Courts of the traditional powers of

an equity Court with particular reference to ‘its facilities

for adjusting and reconciling public and private needs,’

and the ‘practical flexibility in shaping its remedies.’ ”

The Supreme Court of Florida decided that pursuant to

6

well established principles of equity and the directive of

the “ implementation decision” to the effect that the Court

retain jurisdiction “ during this period of transition,” the

Court “ may properly take into account the public interest”

as well as “ personal interest” of petitioner in the elimina

tion of such obstacles as might impede a systematic and

effective transition to the accomplishment of the results

ordered by the United States Supreme Court.

It was the opinion of the Supreme Court of Florida that,

both under the equitable principles applicable to mandamus

proceedings and the express command of the United States

Supreme Court in its “ implementation decision,” the exer

cise of a sound judicial discretion requires the Court to

withhold, for the present, the issuance of a peremptory writ

of mandamus in this cause pending subsequent determina

tion of law and fact as to the time when the petitioner

should be admitted to the University of Florida School of

Law. The Florida Supreme Court, therefore, appointed

the Honorable John A. H. Murplxree, Circuit Judge, as

Commissioner of the Court, to take testimony from peti

tioner and respondents and such witnesses as they may

produce material to the issues alleged in the defense of the

respondents as follows:

“ That the admission of the students of the Negro race

to the University of Florida, as well as to the other

state institutions of higher learning established for

white students only, presents grave and serious prob

lems affecting the welfare of all students and the

institutions themselves, and will require numerous ad

justments and changes at the institutions of higher

learning; and respondents cannot satisfactorily make

the necessary changes and adjustments until all ques

tions as to time and manner of establishing the new

order shall have been decided on the further considera

tion thereof by the United States Supreme Court, at

which time the necessary adjustments can be made as

a part of one over-all pattern for all levels of education

7

as may be finally determined, and thereby greatly

decrease the danger of serious conflicts, incidents and

disturbances. . . . ”

Judge Murphree was directed to file a transcript of such

testimony, without recommendations or findings of fact,

to this Court within four months from the date of the order,

which was October 19, 1955. (Fla.) 83 So. 2d 20.

On January 23, 1956, respondent requested an extension

of time for the filing of such information by the Commis

sioner for the following reasons:

(1) The assistant attorney general who handled the

cause for respondents in the trial Court and the

Supreme Court died during the pendency of this

cause.

(2) The scope of the survey is so extensive that the

information cannot be available for the Court by

the due date of February 19, 1956, in that:

(a) such survey requires a study of student, faculty

and parent attitudes toward integraton of Ne

groes at the University of Florida Law School;

and

(b) it will require a survey or analysis of the facili

ties, students and faculties at Florida Agri

cultural and Mechanical University (Negro in

stitution), including an accurate estimate, if

possible, as to number of students now attend

ing such university who would seek transfer

to the University of Florida School of Law, or

to another school; and

(c) it will require a determination as to whether

such order would result in an increase or de

crease in the student population at the Univer

sity of Florida which had not been contemplated

by school authorities and for which no adminis

trative planning has been accomplished; and

(d) such study will require consideration of the

phenomenal growth of Florida’s population

8

which is directly related to overcrowded con

ditions of the universities and public schools

of the state and in which population increase,

economic growth and swiftly changing social

structure places Florida in a unique position

and creates problems relating to school segre

gation which do not exist to the same degree

in other southern states; and

(e) the survey will require a thorough study and

analysis to be made of the existing facilities

at the University of Florida with regard to

dormitory space, food and recreational facili

ties, and the adequacy of such facilities to

meet the needs of the present enrollment of a

drastically increased or decreased enrollment

which might result if Negroes are admitted to

the University of Florida Law School at this

time; and

(f) such survey will require a review of available

data relating to known achievement level dis

tinctions between white and Negro high school

and college students in Florida, and a com

parative analysis of the effect of such distinc

tions upon administrative efforts to maintain

and improve scholastic standards at Florida

institutions of higher learning in general and

upon the University of Florida Law School

specifically if Negro students are integrated

into the white universities at this time.

Respondents’ request for extension of time indicated that

surveys and studies were presently being made relating

to such problems and that such surveys and studies could

not be completed and analyzed with any degree of accuracy

prior to the expiration of the present school term. Re

spondents also indicated that petitioner, in any event, would

not be eligible for enrollment at the University of Florida

School of Law until September, 1956, when the regular

school term commences. It has been a long standing policy

at the University of Florida that beginning law students

cannot begin at the Summer Session.

9

The Florida Supreme Court granted respondents until

May 31, 1956, in which to submit the requested information.

Petitioner, on January 16, 1956, rather than avail himself

of the opportunity of presenting evidence before the court

appointed Commissioner, sought in this Court the issuance

of a writ of certiorari or any common law writ which might

possibly be applicable to an interlocutory judgment of this

nature.

On March 12, 1956, this Court denied petitioner’s request

for certiorari, and in the same order vacated its mandate

of May 24, 1954, to the Supreme Court of Florida (347 U.S.

971), and substituted in lieu thereof an order instructing

the Supreme Court to consider as applicable to the instant

case certain other cases decided by this Court prior to

the Brown decision and the “ implementing decision” and

relating to graduate professional schools. 350 U.S. 413

(App. A.)

Respondents requested a rehearing for the purpose of

clarifying the intent of such substituted order, but such

rehearing was denied. 351 U.S. 915.

Pursuant to the directions contained in the October 19,

1955, opinion of the Supreme Court of Florida, the court-

appointed Commissioner, John A. H. Murphree, Circuit

Judge, held testimony on May 21, 1956, on the question

relating to the effect, if any, on the public, and State Uni

versity System, of an immediate admission of petitioner to

the University of Florida. Counsel of record for the re

spective parties were duly notified of the hearing, but

neither the petitioner nor his counsel made an appearance.

As part of the record Judge Murphree made the following

statement:

“ I would say for the record that at a conference last

January, about January 27, between myself as Com

10

missioner in this cause, and Mr. Odom, of the Attorney

General’s office, and Mr. Hill, who represents Hawkins,

that this present hearing was scheduled at 9:30 this

morning, and that I advised the parties at that time

that the Commissioner would expect to receive the

evidence submitted by the Board of Control first and

would then hear from Hawkins. On May 14 I wrote

to counsel for the respective parties in this case and

reminded them of my letter of January 27 which sched

uled this hearing for this morning at 9:30; and when

Hill and Hawkins did not show up at 9:30 this morning

I telephoned Mr. Hill’s office to find out if by chance

he had met with mishap on his way to Gainesville,

and his secretary advised that he did not intend to

attend the hearing. As Commissioner, I, therefore,

assume that nothing will be presented on behalf of

Hawkins. Unless the Board of Control has something

further, this hearing is concluded.”

At this hearing the Commissioner accepted into evidence,

after the proper legal predicate was laid, a survey con

ducted by the State Board of Control. This survey was

instituted in an effort to make a determination as to

whether serious administrative and other problems would

be encountered as a result of the Florida Supreme Court

decree that a member of the Negro race should not be denied

admission to the University of Florida. A factual compila

tion of the attitudes of the students, parents of the students,

faculties, alumni, and health service employees, of the three

State universities toward desegregation, was contained in

such survey, including the attitude of parents of white and

Negro high school seniors toward desegregation.

Being germane to the question, the survey also included

a study made by the Board of Control of the physical facili

ties at the three State universities to determine their current

use, what additional facilities might be available because of

anticipated construction, and whether any shortage might

exist by the fiscal year 1959-60. The study included a

11

survey of classroom, food service, health service, housing,

library, and recreational facilities.

On May 28, 1956, the Commissioner filed a transcript of

the above-mentioned testimony “ without recommendations

or findings of fact” to the Supreme Court of Florida in

accordance with such Court’s directive of October 19, 1955.

83 So. 2d 20.

On June 20, 1956, petitioner applied to the Supreme

Court of Florida for the issuance of a peremptory writ of

mandamus ordering his immediate admission to the Uni

versity of Florida. A hearing was held on such application

before the Supreme Court of Florida on September 4, 1956,

at which time both parties to the cause presented their

respective arguments.

On February 19, 1957, respondents moved the Supreme

Court of Florida to refer this cause to a Commissioner

appointed by the court “ for the purpose of receiving testi

mony from the Petitioner and Respondents and such other

witnesses as either party may produce relative to matters

previously unknown to Respondents, and recently discov

ered evidence affecting the bona fides of this cause, said

evidence having been received by the State of Florida

Legislative Investigating Committee on February 4 through

February 7, 1957, or at times subsequent thereto.”

The motion for referral to a Commissioner for the purpose

of taking testimony on the bona fides of this cause was

denied by the Supreme Court of Florida on February 26,

1957, which order of denial was subsequently corrected on

March 5,1957. On May 31, 1957, subsequent to such denial,

an investigating committee of the Florida Legislature cre

ated for the purpose of investigating groups, both white

and Negro, suspected of functioning for the purpose of

creating racial strife and discord within the State of

12

Florida, submitted a report of its findings and recommen

dations. (App. C.) One of the Committee’s recommenda

tions requested that a copy of the testimony given before

such committee “ be made available to the proper officials

of the Florida Bar and the state attorneys having juris

diction where the hearings were held, with the request

that the same be carefully studied and if violations of law

or ethics have occurred that proper proceedings be insti

tuted against any such offender.” Such testimony included

statements made by Horace E. Hill, the original counsel

of record for petitioner in this cause. On May 27, 1957,

said counsel of record, alleging ill health, requested and

received the permission of the Supreme Court of Florida

to withdraw from this cause.

On March 8, 1957, the Supreme Court of Florida rendered

its decision to defer final judgment in this cause, and to

delay the issuance of its peremptory writ of mandamus in

light of properly presented factual information prompting

the application of principles of equity necessary in the

consideration of the issuance of such writ, and delaying

the issuance of such writ until the facts will permit, or

until the petitioner is prepared to present testimony which

will obviate the necessity of applying such principles.

13

ARGUMENT

P A R T I: THE LAW

Argument of law in response to questions presented in

Petitioner’s brief:

This Court, in its order to the Supreme Court of Florida

of March 12, 1956, said: . . The judgment is vacated

and the case is remanded on the authority of the Segre

gation Cases decided May 17, 1954, Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483. As this case involves the admis

sion of a Negro to a graduate professional school, there is

no reason for delay. He is entitled to prompt admission

under the rules and regulations applicable to other quali

fied candidates.” (Emphasis supplied.) (App. A.) Re

spondents and the Supreme Court of Florida, in light of

sound reason and the necessary employment of legal and

equitable principles, can only logically interpret the lan

guage of this order as having reference to the question of

race. Argumentum ah inconvenienti plurimum valet in lege.

Aside from race, it is manifest that constitutional, legal

and practicable reasons may exist at times to deny or

delay the admission of an applicant to a state university,

whether he be white or Negro. It is also evident that if

petitioner’s interpretation were accepted it would abrogate

the long-established rule which denies to federal courts the

right to regulate or control long-established rules of pro

cedure adopted by the state courts for the administration

of justice therein, cf. Naim v. Naim, 197 Va. 734, 90 S.E. 2d

849; 350 U.S. 985, 76 S.Ct. 472, 100 L.ed. 852.

In the case at bar, the Supreme Court of Florida adhered

to the above-mentioned order of this Court that as to the

issue of race there is no reason for delaying petitioner’s

admission to the University of Florida. However, such

order did not foreclose the authority of the Supreme Court

of Florida to exercise its discretion to determine that it

14

was necessary and essential to consider other issues of

vital importance to the public interest and safety of the

State of Florida before issuing its peremptory writ of

mandamus.

Even in a case where a clear legal right is shown, the

exercise of jurisdiction to grant a writ of mandamus rests,

to a considerable extent, within the sound discretion of the

Court, subject, however, to the well-settled principles which

have been established by the courts or fixed by statute;

and evidence will usually be received, upon request of the

respondent, to show that the writ should not issue. Re

spondents understand of course that such discretion is not

absolute but yet the court may refuse the issuance of such

writ even though warranted by the rules of law, if hardship

or injustice would result to the opposite or to third parties

from granting it. See Injunctions and Other Extraordinary

Remedies, Second Edition, by T. C. Spelling.

The Supreme Court of Florida has held on numerous

occasions that the writ of mandamus is discretionary and

is only granted in the sound discretion of the court, and

will decline its use if to do so would tend to work a serious

mischief. State ex rel Long v. Carey, 121 Fla. 515, 164 So.

199; Brown v. Dewell, 131 Fla. 566, 179 So. 695, 115 A.L.R.

857; State ex rel West Flagler Kennel Club v. Florida State

Racing Commission, 74 So. 2d 691; State ex rel Norman v.

Holmer, 160 Fla. 434, 35 So. 2d 396; Somlyo v. Schott, 45

So. 2d 502; City of Safety Harbor v. State ex rel Smith,

136 Fla. 636, 187 So. 173; State ex rel Carson v. Bateman,

131 Fla. 625, 180 So. 22; State ex rel Gibson v. City of

Lakeland, 126 Fla. 342, 171 So. 227; State ex rel Bottome

v. City of St. Petersburg, 126 Fla. 233, 170 So. 730.

Where a superior court issues its mandate to the lower

court with instructions to accomplish a certain act but

without indicating how such act shall be performed, it has

15

been held that a large measure of discretion exists as to

the manner of performance. Holliday v. Pacific Atlantic

S.S. Co., J3.C. Del. 1953, 117 P.Supp. 729, affirmed 212 F. 2d

206. The duty of the court below to obey and give effect

to the mandate of the Supreme Court is effective only to

the extent practicable. In re Morris, Ala., 9 Wall. 605,

19 L.ed. 799.

The action of the Supreme Court of Florida in delaying

the issuance of its writ of mandamus was not contrary to

the letter or spirit of the mandate of this court issued on

March 12, 1956. Subsequent to such order of this Court

the Supreme Court of Florida obtained evidence indicating

that issues other than race existed which required the

application of equitable principles prompting the delay of

such writ. This action was in harmony with the principle

that the mandate of the Supreme Court must be promptly

and implicitly enforced by the Court below unless modified

or restrained by subsequent evidence. So. Fork Canal Co.

v. Gordon, C.C.Cal. 1868, Fed. case #13,189, 2 TJ.S. 479,

8 A.L.R. 279.

The Florida Supreme Court upon receipt of testimony

received by its Commissioner considered it essential to

apply equitable principles and thereby delay the issuance

of its writ. It is a well-established principle that a court

of equity is never active against conscience or public con

venience. Bowman v. Wathen, 1 How. 189, 11 L.ed. 97.

This Court has always, felt it proper to apply principles of

equity against the enforcement of legal doctrines upon the

disclosure that the public interest might be affected ad

versely by the immediate enforcement of a legal decree.

It is also manifest that courts of equity may appropriately

withhold their aid when the plaintiff is using the writ

asserted in a manner contrary to the public interest. Morton

Salt Co. v. Suppiger Co., 314 U.S. 488, 62 S.Ct. 402, 86

L.ed. 363. Although mandamus is a common-law remedy,

16

the Supreme Court of Florida has consistently held that

the application and enforcement of such writ should be

governed by equitable principles. State v. Daytona Beach,

129 Fla. 896, 176 So. 847; State v. West Palm Beach, 141

Fla. 244,193 So. 297; Miami v. Huttoe, 40 So. 2d 899; Safety

Harbor v. State, 136 Fla. 636, 187 So. 173; Bradenton v.

State, 118 Fla. 838, 160 So. 506, 100 A.L.R. 400: Nelson v.

Lindsey, 151 Fla. 596, 10 So. 2d 131; State v. Miami, 153

Fla. 90, 13 So. 2d 707; State v. Board of Control, 83 So. 2d

20. Such is also true of the federal application of such writ.

Touchton v. Fort Pierce, 109 F. 2d 370.

The Supreme Court of Florida, in light of testimony re

ceived by its Commissioner, considered it necessary to

adopt these long adhered to principles in order to avoid

public mischief and the occurrence of serious administra

tive problems in the operation of the State University

System. These considerations are manifestly essential if

an orderly and peaceful transition to the new order created

by the Brown decision is to be made. The extent to which

a court of equity may grant or withhold its aid and the

manner of molding its remedies may be dictated or effected

by the public interest involved. United States v. Morgan,

307 U.S. 183, 59 S.Ct. 795, 83 L.ed. 1211.

The State of Florida has experienced success in main

taining an emotional equilibrium in the wake of this Court’s

ruling prohibiting segregation in the public schools. This

is attributable to the application of long-established equita

ble principles by the Supreme Court of Florida in dealing

with this problem. Traditionally, equity has been charac

terized by practicable flexibility in shaping its remedies

and by the facilities for adjusting and recognizing public

and private needs. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.ed. 1083. In some cases

it is essential that a court apply equitable principles in

17

order to strike a proper balance between the needs of the

plaintiff and the consequence of giving the desired relief.

Eccles v. Peoples Bank, 333 U.S. 426, 68 S.Ct. 641, 92 L.ed.

784. The necessary flexibility of established forms em

ployed by courts of equity permit proceedings and remedies

to be adapted to the circumstances of each individual case

and their formulation in such a manner as to safeguard,

adjust and enforce the rights of all parties. Alexander v.

Hillman, 296 U.S. 222, 56 S.Ct. 204, 80 L.ed. 192.

The Supreme Court of Florida in its last decision, predi

cated upon the evidence before it, decided that it should

delay the issuance of its writ at this time. Having so

decided, the Supreme Court of Florida deferred final judg

ment and offered petitioners an opportunity to present

evidence before it, at any time, which would indicate that

such a writ could be issued without attendant mischief.

Deferring judgment and permitting time is not novel, this

Court having consistently permitted time in the implemen

tation of decrees involving long-established public policy

which affected the public interest. Recognizing that certain

decrees present an urgent need for adjustment this Court

has permitted time in which to overcome the many prob

lems attendant in such adjustment. United States v. Amer

ican Tobacco Co., 221 U.S. 106, 31 S.Ct. 632, 55 L.ed. 663;

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1, 31 S.Ct. 502,

55 L.ed. 619. The need for a period of gradual transition

in some cases has been held by this Court to be a valid and

necessary consideration. Hew Jersey v. New York, 283 U.S.

473, 51 S.Ct. 519,75 L.ed. 1176; Georgia v. Tennessee Copper

Co., 206 U.S. 230, 27 S.Ct. 618, 51 L.ed. 1038; People of the

State of New York v. State of New Jersey and Passaic

Valley Sewerage Commissioners, 256 U.S. 296, 41 S.Ct. 492,

65 L.ed. 937.

The Supreme Court of Florida having deferred judgment,

petitioner’s request for certiorari is premature inasmuch

18

as such writ is applicable to final judgments. Fox Film \

Corp. v. Muller, 55 S.Ct. 444, 294 U.S. 696, 79 L.ed. 1234, j

certiorari dismissed, 56 S.Ct. 183, 296 U.S. 207, 80 L.ed. 158; j

Bruce v. Tobin, 38 S.Ct. 7, 245 U.S. 18, 62 L.ed. 123; Urie v./

Thompson, 69 S.Ct. 1018; 337 U.S. 163, 93 L.ed. 1282.

Petitioner cites five eases in his brief for the proposition

that this Court has authority under Title 28, United States

Code, to enter its own judgment in a case of this nature,

in that “ in the past (it) has issued such judgments, espe

cially in situations where a state court has failed to act in

conformity with a prior mandate of this Court.” The cases

cited for such proposition are: Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee,

1 Wheat. 304, 4 L.ed. 97; McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat.

316, 4 L.ed. 579; Magwire v. Tyler, 17 Wall. 253, 21 L.ed.

576; Williams v. Bruffy, 102 U.S. 248, 26 L.ed. 135; and

Stanley v. Schwalby, 162 U.S. 255, 40 L.ed. 960,16 S.Ct. 754.

A valid distinction exists between each of the cited cases

and the case at bar. In both Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee,

supra, and Williams v. Bruffy, supra, the cases were ap

pealed to this Court and subsequently reversed and re

manded with directions to the Virginia Court of Appeals.

In both cases the Virginia Court of Appeals questioned

the authority of this Court to issue such mandate. In the

Martin case, the Virginia Court said, “ This Court is unani

mously of the opinion that an appellate power of the Su

preme Court of the United States does not extend to this

Court . . . ” In the Williams case, the same court said,

“ For these reasons this Court, with highest respect and

consideration for the Supreme Court of the United States,

must decline to take any further action with respect to

the mandate of said court.”

In Magwire v. Tyler, supra, the case was remanded by

the United States Supreme Court on second hearing to the

Supreme Court of Missouri with directions. The Supreme

19

Court of Missouri carried out the minority portion of the

mandate and then ignored any authority of this Court in

such regard by dismissing the case. On the third hearing

of this case this Court said, “ The Missouri Supreme Court

has no power to evade or reverse the United States Supreme

Court. ’ ’

It is true that in the case of McCulloch v. Maryland,

supra, this Court entered its own judgment but it is equally

true that such judgment was not the result of the refusal

of a state court to obey a prior mandate of this Court.

Stanley v. Schwalby, supra, is cited by petitioner as a

case wherein this Court remanded a case and ordered its

own judgment (see footnote 1, page 2, Petitioner’s brief).

It is to be noted, however, from a reading of the opinion

of this case, that the judgment was reversed by this Court

and the case was remanded “ with instructions.”

Respondents consider it equally important to point out

that the aforementioned cases cited by petitioner in his

brief range chronologically from 1816 to 1895, and deal

with a variety of subjects, none of which are germane to

the subject at hand: ‘rA treaty and title to land” (Martin

v. Hunter); “ Federal Banks v. State Taxation” (McCulloch

v. Maryland); “ Right to title of real property involving a

Secretary of Interior’s ruling” (Magwire v. Tyler); “ Debts

and rights of citizens of northern and southern states after

the Civil W ar” (Williams v. Bruffy); and “ Right of title

to real property occupied by Federal troops” (Stanley v.

Schwalby).

Not only are the points for which the above cases are

cited distinguishable from the case at bar but the facts

involved and the entire surrounding circumstances in each

of the cases are far afield from the interest at hand. The

above cases are cited by petitioner in his brief for the

20

proposition that this Court should consider that the Su

preme Court of I lorida has disobeyed this Court ’s mandate

of March 12, 1956, and should therefore enter its own judg

ment. A careful study of the proceedings of the Supreme

Court of Florida subsequent to the issue of this Court’s

mandate of March 12, 1956, will show that the actions of

the Supreme Court of Florida have been completely dis

similar to the actions of the inferior courts in the cited

cases. The Supreme Court of Florida has neither disobeyed

nor evaded the mandate of this Court. Such cases did not

involve the public interest and welfare of a sovereign state

to the degree manifest in the case at bar and should there

fore have no applicability or persuasion to the decision of

the Supreme Court of Florida which is predicated entirely

on the grounds that it has the duty, responsibility, and the

inherent authority to act in such a way as to avoid public

mischief in this state. The Supreme Court of Florida has

indicated its willingness to carry out this Court’s mandate

without causing public mischief.

On June 4, 1956, this Court entered an order in the case

of United Automobile, Aircraft and Agricultural Imple

ment Workers, et al v. Wisconsin Employment Relations

Board et al, 351 U.S. 266, 76 S.Ct. 794, 100 L.ed. 1162 and,

where applicable to the instant case, stated: “ the dominant

interest of the state in preventing violence and property

damage cannot be questioned. It is a matter of genuine

local concern. The states are the natural guardians

against public violence. It is the local communities that

suffer most from the fear and loss occasioned by coercion

and destruction. We would not interpret an Act of Congress

to leave them powerless to avert such emergencies without

compelling directions to that effect. We hold that Wis

consin may enjoin the violent Union conduct herein in

volved. The fact that Wisconsin has chosen to entrust its

powers to a Labor Board is of no concern to this Court.”

21

This case clearly recognizes the constitutional powers of

of states to exercise reasonable and proper authority to

avoid disorder, and, in the language of this Court, to act

as “ the natural guardians of the people against violence.”

The only distinction which may be made in the Wisconsin

case, supra, and the case at bar, is that in the Wisconsin

case this Court was considering a conflict between an Act

of Congress and a Wisconsin state statute providing ad

ministrative safeguards. In the case at bar there is no

conflict between Federal and state laws, since Congress

has not enacted any legislation on the subject of state school

segregation, and the only apparent conflict is whether this

Court’s previous pronouncements on the issue of racial

segregation in public institutions of learning should be in

terpreted and enforced in a manner that refuses to recog

nize, and over-rides, the inherent powers of the State of

Florida to safeguard the peace and welfare of its people

through the administrative processes provided by state

constitutional and legislative provisions, and by the appli

cation of equitable principles in the public interest by the

Supreme Court of Florida.

In certain areas of government, States’ rights have been

surrendered to the Federal Government, but in such cases

the avenue by which the United States Supreme Court en

ters the State Judiciary is by certiorari, a privilege granted

to the Supreme Court by the States. In no instance has

the Supreme Court been given the “ right” to reply to cer

tiorari except by “ mandate” and “ direction” to the state

courts. Should the United States Supreme Court issue a

direct order to the Board of Control and by-pass the State

Court, it would not only be usurping its power but it would

deny the people of the State of Florida their rights to the

judicial discretion which might otherwise be exercised by

the Supreme Judiciary of this State, a body which is far

more familiar with the problems of the people of Florida

than any other court in the Union.

22

It is a fundamental principle of law that a state has all

the sovereign powers of an independent nation over all

persons within its territorial limits subject to the restraints

of the Federal Constitution, Ryan v. State, 58 S.Ct. 233,

302 U.S. 186, 82 L.ed. 187; Parker v. Brown, 63 S.Ct. 307,

317 U.S. 341, 87 L.ed. 315.

The dual nature of the American Government, while

simple in theory, frequently presents practical complexities

which are difficult to harmonize. People v. Daly, 105 N.E.

1048, 212 N.Y. 183. No boundary separating the field of

state and federal control can be marked out for the reason

that in many cases they overlap, and for this reason it may

be difficult at first to determine which court has authority

to operate within the state. Konkel v. State, 170 N.W. 715,

168 Wis. 335.

Under the Tenth Amendment, the Constitution recog

nizes the necessary independent existence of the states

within their proper spheres and their attendant indepen

dent authority. Hoxie v. N.Y., 73 A. 754, 82 Conn. 352. In

this regard the Federalist Papers contain the following

statement:

“ The powers delegated by the proposed constitution

to the federal government are few and defined. Those

which are to remain in the state government are nu

merous and indefinite. The former will be exercised

principally upon external objects, as war, peace, nego

tiation, and foreign commerce; with which last the

power of taxation will, for the most part, be connected.

The powers reserved to the several states will extend

to all the objects which, in the ordinary course of

affairs, concern the lives, liberties, and properties of

the people, and the internal order, improvement and

prosperity of the state.”

Thomas Jefferson’s first Inaugural Address stressed the

23

importance of permitting the individual states to manage

their internal operations when he stated:

“ I will compress them (said the President) within the

narrowest compass they will bear, stating the general

principle, but not all its limitations. Equal and exact

justice to all men, of whatever state or persuasion, re

ligious or political; peace, commerce, and honest friend

ship with all nations, entangling alliances with none;

the support of the State Governments in all their rights,

as the most competent administrations for our domes

tic concerns and the surest bulwarks against anti

republican tendencies; . . (emphasis supplied)

The importance of this federal-state relationship was

noted by Chief Justice Marshall in McCulloch v. Maryland,

4 Wheat. 316, when he stated:

“ No political dreamer was ever wild enough to think

of breaking down the lines which separate the states

and of compounding the American people into one

common mass.”

George Washington pointed up this important consid

eration when he stated in his Farewell Address:

“ If, in the opinion of the people, the distribution or

modification of the constitutional powers be in any

particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment

in the way which the constitution designates. But let

there be no change by usurpation, for, though this, in

one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the

customary weapon by which free governments are

destroyed. The precedent must always greatly over

balance in permanent evil any partial or transient

benefit which the use may at any time yield.”

Permitting the individual state to handle without inter

ference matters of strictly local concern is in harmony with

the principle that every state as an integral member of the

24

Federal Nation has the duty to aid in the preservation of

the Nation and to that end to do everything within its means

and power. State ex rel American Legion 1941 Convention

Corporation of Milwaukee v. Smith, 293 N.W. 161, 235

Wise. 443.

It is equally true that the Federal Government owes the

same obligation to the states to aid in the preservation

thereof by contributing to the peace and harmony therein.

While there are two distinct sovereignties, federal and

state, they are designed and expected to be adapted to

each other to work together in harmony, the Federal Gov

ernment exercising those powers granted to it by the States,

each mutually and independent of the other. See Feldman

v. United States, 64 S.Ct. 1082, 322 U.S. 487, 88 L.ed. 1408,

154 A.L.R. 982; In re Opinion of the Justices, 8 N.E. 2d

753, 297 Mass. 567; State ex rel Gibbs v. Gordon, 138 Fla.

312, 189 So. 437. State governments possess all the powers

incident to political government and not delegated to the

United States. See Bute v. People of State of 111., 68 S.Ct.

763, 333 U.S. 640, 92 L.ed. 986.

Although the sovereign states have delegated exclusive

jurisdiction in certain enumerated eases, such has not been

done in the field of education and, hence, in this and other

such matters the dual sovereignty of the State and the

United States continue to exist. See Westfall v. United

States, 47 S.Ct. 629, 274 U.S. 256, 71 L.ed. 1036. The line

of operation between the United States and the several

states as to jurisdiction and sovereignty is clear in its

constitutional aspects and, although it is sometimes diffi

cult to define, it is sharply maintained. In re Opinion of

the Justices, supra.

It is and has been established policies of both State

and Federal Governments to treat possible conflicts be

tween their powers in such a manner as to produce as little

25

conflict and friction as possible. Bute v. People of Illinois,

supra. Where two sovereignties operate in the same area,

one with delegated and the other with reserved powers,

if conflicts arise in the exercise of some spheres of power,

they should be resolved in a way that neither sovereignty

will be hampered in the exercise of a power in which the

public welfare requires that it be the supreme exponent.

See In re Briley’s Estate, 155 Fla. 798, 21 So. 2d 595.

The state and federal government should operate in

perfect harmony. Penn v. Tollison, 26 Ark. 545, 577. This

Court considered the importance of this maxim when, in

Burgess v. Seligman, 107 U.S. 20, 2 S.Ct. 10, 27 L.ed 359,

it stated: “ For the sake of harmony and to avoid confusion,

the Federal Courts will lean towards an agreement of views

with the state courts if the question seems to them balanced

with doubt. Acting on these principles, founded as they

are on comity and good sense, the Courts of the United

States, without sacrificing their own dignity as independent

tribunals, endeavor to avoid, and in most cases do avoid

any unseemly conflict with the well-considered decisions

of the state courts.”

Petitioner would have this Court assume that the Su

preme Court of Florida has arbitrarily flouted its mandate.

This is a subtle but oft-used method of influencing another

to gain an objective by suggesting that such other’s rightful

prerogatives and authority have been flagrantly violated

by the one sought to be worsted. It is an appeal in part

to pride and the attribute of superiority. However, we

do not believe this high Court will be so subtly and psycho

logically digressed from the law to an unwarranted assump

tion that its superiority has been flouted.

This Court will recognize that the Supreme Court of

Florida is conscious of its duty and responsibility in the

case; that the Florida Court after due investigation is

26

seriously concerned with factual conditions other than race;

and that it is not flouting but it is attempting to avoid

untoward events and protect petitioner and others from a

premature and mischief provoking contretemps.

This Court we believe will not arrogantly brush aside

as impertinent a delay by the Supreme Court of Florida

based on factual considerations and local conditions. Courts

do not move on predicates which allow no consideration of

facts or conditions. Equity is not arrogant. It proceeds

cautiously in the light of facts and the public interest.

We sincerely believe that in this dilemma where there

is in process an experimentation in seeking to adjust legal

rights with customs, usages, traditions, prior laws, the high

Court of this Nation will welcome the counsel, the prudence,

and the careful considerations of a state appellate court

unless and until it is shown that the latter is acting in bad

faith. We submit bad faith is not shown on the part of

the Supreme Court of Florida by petitioner, rather peti

tioner in his extreme desire to win his point at all costs

would have this great Court completely disregard and

peremptorily strike down the very moderate, mild and

reasonable determination of the Florida Court that some

delay is expedient for reasons other than race.

27

PART II

FACTUAL CONSIDERATIONS

The question of the immediate admission of a student

of the Negro race to the University of Florida cannot be

considered as isolated from broad general considerations

involving both legal and factual matters which result in

the social dilemma of racial segregation.

The prime issue here is one of fact, not law. The two

should not be confused. This Court overlooked this con

sideration when it stated in its March 12, 1956, opinion

in this case (State of Florida ex rel. Virgil Hawkins vs.

Board of Control, 350 U.S. 413, 100 L.ed. 486, 76 S.Ct.

464), that it had already ordered the admissionfos a matter

of legal right) of negroes to institutions of higher learning

in three other states and that therefore “ there is no reason

for delay” in Florida.

Such an inference assumes without proof of any kind

that the factual situation some years ago in university

integration cases in other states is identical to the factual

situation in Florida in 1956.

To rely on a previous legal ruling as to constitutional

rights in Oklahoma as authority for an assumption as to

factual conditions in Florida is illustrative of the common

fallacy in logic termed “ irrelevant conclusion” or possibly,

if it is blindly adhered to, argmnenhum ad baculum (appeal

to force).

In its opinion in this case filed by the Supreme Court of

Florida on March 8, 1957, the court said:

“ It is unthinkable that the Supreme Court of the

United States would attempt to convert into a writ

of right that which has for centuries at common law

and in this state been considered a discretionary writ;

28

nor can we conceive that that court would hold that

the highest court of a sovereign state does not have

the right to control the effective date of its own dis

cretionary process. Yet, this would be the effect of

the court’s order, under the interpretation contended

for by the Eelator. We will not assume that the court

intended such a result. ’ ’

Speaking further the court said:

“ We cannot assume that the Supreme Court intended

to deprive the highest court of an independent sover

eign state of one of its traditional powers, that is, the

right to exercise a sound judicial discretion as to the

date of the issuance of its process in order to prevent

a serious public mischief.”

In support of these contentions and its findings that the

writ sought by the petitioner in this case should be delayed

in the interest of the public welfare, the Supreme Court of

Florida reviewed briefly the facts developed by a commis

sioner appointed by the court and submitted to it. It took

note of the fact that although the Eelator (petitioner) had

due notice and an opportunity to be heard at all hearings

scheduled by the commissioner, he did not appear nor did

he attempt to present any testimony in support of his right

to immediate admission. The voluminous testimony, sur

veys and factual findings submitted to the Florida Supreme

Court by its commissioner presented an overwhelming case

in favor of caution and delay in the issuance of a writ

which would order the petitioner’s admission to the Uni

versity of Florida. All of this testimony and factual ma

terial were properly presented to the Supreme Court of

Florida through its commissioner and are now a part of

the record of this case and available for the information

and guidance of this Court.

The Supreme Court of Florida reached the conclusion

that its “ study of the results of the survey material to the

29

question here, and other material evidence, leads inevitably

to the conclusion that violence in university communities

and a critical disruption of the university system would

occur if Negro students are permitted to enter the state

white universities at this time, including the Law School of

the University of Florida, of which it is an integral part.

This Court has an opportunity to prevent the incidents of

violence which are, even now, occurring in various parts of

this country as a result of the states’ efforts to enforce the

Supreme Court’s decision in the Brown case.”

The allusion to general conditions prevailing throughout

the country and the realities of the situation are recognized

in a book which has come to be considered authoritative

on racial matters. This book, “ An American Dilemma,”

by Gfunnar Myrdal, page 58, makes the following statement:

‘ ‘ This attitude of refusing to consider amalgamation—

felt and expressed in the entire country—constitutes

the center in the complex of attitudes which can be

described as the ‘common denominator’ in the prob

lem. It defines the Negro group in contradistinction to

all the non-colored minority groups in America and all

other lower class groups. The boundary between Negro

and white is not simply a class line which can be suc

cessfully crossed by education, integration into the na

tional culture, and individual economic advancement.

The boundary is fixed. It is not a temporary expedi

ency during an apprenticeship in the national culture.

It is a bar erected with the intention of permanency.

It is directed against the whole group.” (Emphasis

supplied)

And

“Almost unanimously white Americans have communi

cated to the author the following logic of the case

situation which we shall call the ‘white man’s theory

of color caste.’ (Emphasis supplied)

30

“ (1) The concern for ‘race purity’ is basic in the

whole issue; the primary and essential command

is to prevent amalgamation; the whites are de

termined to utilize every means to this end.

“ (2) Rejection of ‘social equality’ is to be understood

as a precaution to hinder miscegenation and par

ticularly intermarriage.

“ (3) The danger of miscegenation is so tremendous

that the segregation and discrimination inherent

in the refusal of ‘social equality’ must be ex

tended to nearly all spheres of life. There must

be segregation and discrimination in recreation,

in religious service, in education, before the law,

in politics, in housing, in stores and in bread

winning. ’ ’

Myrdal throughout his book clearly evidences a genuine

concern for the plight of the Negro in America but we feel

that the tenor of his book is in sharp contradiction to the

reasoning and arguments of the petitioner in this case who

insists that his right to enter the University of Florida is

personal and present, should be granted immediately, and

no other factors should be considered. In this connection

we agree with Myrdal’s statement on page 61 of his book

cited above:

“ Negroes are in desperate need of jobs and bread, even

more so than of justice in the courts, and of the vote.

These latter needs are, in their turn, more urgent even

than better schools and playgrounds, or, rather they

are primary means of reaching equality in the use of

community facilities. Such facilities are, in turn, more

important than civil courtesies. The marriage matter,

finally, is of rather distant and doubtful interest. ’ ’

The truth of Myrdal’s assertion as to the almost total

opposition of white citizens to an enforced integration of

schools at any level is confirmed by an abundance of reliable

31

evidence dealing specifically with Florida which will be

dealt with subsequently in this brief.

Voicing this opposition as an official expression of the

feelings of the white people of Florida, the Florida Legis

lature adopted a resolution of interposition in its 1957 ses

sion. Said resolution has been made a part of and is at

tached to this brief as Appendix B.

This resolution which is not without historical precedent,

we construe to be the strongest possible form of protest

which can be legally filed by the people of a sovereign state

in opposition to an action of any branch of the Federal

government which the people consider to be inherently

wrong. We do not view this resolution as being an unlawful

defiance of the authority of this Court but we do respect

fully submit that it is an official, sincere expression of the

feelings of a free people which should be given due con

sideration by this Court in determining the wisdom and

authority of the action of the Supreme Court of Florida

in delaying the issuance of its writ of mandamus which

would compel petitioner’s immediate admission to the Uni

versity of Florida.

Further concern because of racial problems in Florida

is reflected in a report of an Investigative Committee of

the Florida Legislature. This report which, was submitted

to the Florida Legislature on May 31, 1957, is made a part

of and attached to this brief as Appendix C.

The report contains the following statement relating to

the bona tides of this case.

“ In the opinion of counsel, the record discloses that

certain attorneys for the NAACP have engaged in un

ethical conduct in violation of the canons of ethics

governing the practice of law in Florida. I t likewise

discloses the very strong possibility that some of the

32

witnesses before this committee committed perjury.

Therefore, it is recommended that a copy of the perti

nent testimony be made available to the proper officials

of the Florida Bar and the state attorneys having

jurisdiction where the hearings were held, with the

request that the same be carefully studied and if viola

tions of law or ethics have occurred that proper pro

ceedings be instituted against any such offender.

“ The Florida State Teachers Association has con

cerned itself with integration law suits. It, together

with the NAACP, has been one of the prime movers in

instigating the filing of the Virgil Hawkins case, to

which the Florida State Teachers Association has been

one of the principal financial contributors. The record

shows that Virgil Hawkins and the other plaintiffs

involved in this case had virtually no control over the

course of this litigation and absolutely no financial

responsibility for the same, the case having been han

dled and controlled entirely by persons and organiza

tions other than the individual plaintiffs.

“ A much more damaging report as to the NAACP’s

activities would undoubtedly be dictated by the record

except for the fact that all records of NAACP have

been secretly removed from the jurisdiction of this

state for the express purpose of preventing this com

mittee from examining the same.”

Overtones of racial unrest, violence and the sincere op

position of law-abiding citizens throughout the country to

the immediate implementation of this Court’s decision in

the Brown case are apparent on every hand and must be

considered in the realm of general knowledge worthy of the

consideration of this Court.

An article in the June 15, 1957, issue of the Saturday

Evening Post written by John Bartlow Martin entitled

“ The Deep South Says Never” appears to be a factual

report of the general attitude toward integration of the

races throughout the South. In this article Mr. Martin says,

33

“ Segregation is not a principle upheld by louts and bullies.

It is viewed as inherently right by virtually every white

person in the four-state South of which we speak.”

Although Mr. Martin’s study did not include Florida

specifically, we know his findings are to a large extent

equally applicable in this state.

Florida’s specific condition in this regard is the subject

of an exhaustive and objective study of sociological, physi

cal and psychological conditions relevant to the University

of Florida and Florida’s system of higher education made

by the State Board of Control. This study which was the

basis of the order of the Supreme Court of Florida which

petitioner seeks to circumvent is too bulky to include in its

entirety in this brief.

We feel, however, that it is important to bring to the

attention of this Court certain portions of said study so

that it may be properly advised as to the difficulties at hand

without having to refer to the record which is voluminous.

This can best be accomplished through statements of wit

nesses at the hearing which summarizes the findings of the

study and their own conclusions.

The sworn testimony of the Honorable Fred H. Kent

(who was chairman of the State Board of Control at the

time of the hearing before the Commissioner appointed

by the Supreme Court of Florida) includes the following

statement:

“ A. The Board of Control, and all of its members, definitely

are of the opinion that we are confronted with a major

problem posed by the decision of the Supreme Court

decreeing what—or rather, I might say, decreeing that

a Negro is entitled to be admitted to the University of

Florida and the Florida State University. Our major

problem at the present time has been to determine

34

what the effect of admitting such a Negro to either of

those institutions would be. We have been trying to

study that problem for the purpose of presenting the

various aspects of it to the Supreme Court of Florida

in this particular proceeding. We haven’t reached that