Alabama v. United States Jurisdictional Order

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alabama v. United States Jurisdictional Order, 1970. 76a56555-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/379146e2-31af-43e4-a754-f6980f9dad21/alabama-v-united-states-jurisdictional-order. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

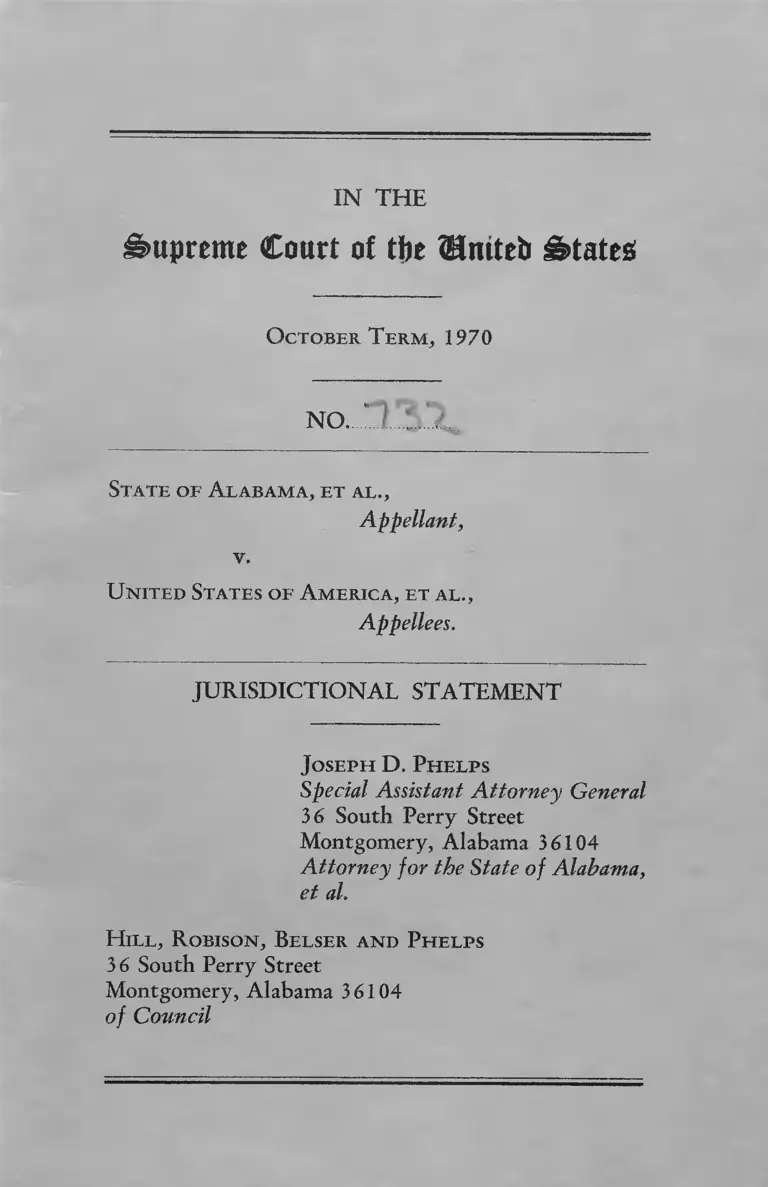

IN TH E

Supreme Court of tlje Umteb States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1970

n o ....". ....

St a t e o f A la b a m a , e t a l .,

Appellant,

v.

U n it e d St a t e s o f A m e r ic a , e t a l .,

Appellees.

JURISDICTIO N AL STATEM ENT

J o se p h D . Ph e l p s

Special Assistant Attorney General

3 6 South Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Attorney for the State of Alabama,

et al.

H il l , R o biso n , B e l s e r a n d Ph e l p s

3 6 South Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

of Council

IN TH E

Supreme Court of ttje Mmteb States:

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1970

NO.

St a t e o f A la b a m a , e t a l .,

Appellant,

v .

U n it e d Sta tes o f A m e r ic a , e t a l .,

Appellees.

JURISDICTIO N AL STATEM ENT

J o se p h D. Ph e l p s

Special Assistant Attorney General

36 South Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Attorney for the State of Alabama,

et al.

H il l , R o biso n , B e l s e r an d Ph e l p s

3 6 South Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

of Council

IN D EX

Statement as to Jurisdiction ........................................................... 1

Opinions Below ................................................................................ 2

The Act in Question ...................................................................... 3

Jurisdiction ....................................................................................... 4

Questions Presented ........................................................................ 5

Statement of the Case ...................................................................... 6

The Questions Presented are Substantial ...................................... 7

Conclusion ....................................................................................... 12

Appendix:

A. Order and Opinion of Court Below ............................... 14

B. March 16, 1970 Order and Opinion of District

Court in Davis v. Board of School Commis

sioners of Mobile County ................................................ 22

C. List of Court Orders Pursuant to Which Ala

bama Schools are Operating .............................................. 24

1

TABLE OF CASES

Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Haworth, 300 U. S. 227,

57 S. Ct. 461, 81 L. Ed. 617 .....................................................

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U. S. 19, 90 S. Ct. 29, 24 L. Ed. 2d 19 8,

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education,

Civil Action No. 2072-N, U. S. D. C. Middle

District of Alabama, February 25, 1970 .................................

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, ............ F. Supp................, Civil Action

No. 3003-63 U. S. D. C., Southern District of

Alabama, March 16, 1970 .......................................... 2, 4, 6,

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F. 2d 1387,

(6th Cir. 1969) ..........................................................................

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U. S. 430, 88 S. Ct. 1689, 20 L. Ed 2d 716 8,

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of

Memphis, 397 U. S. 232, 90 S. Ct. 891, 25 L. Ed

2d 246 ...........................................................................................

Public Service Commission of Utah v. Wycoff Co.,

344 U. S. 237, 73 S. Ct. 236, 97 L. Ed. 291

Public Utilities Com. v. United States, 3 55 U. S. 534,

78 S. Ct. 446, 2 L. Ed 2d. 470 ..................................................

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 312 F. Supp. 503 (D. C. N. C. 1970) ...........................

12

10

11

11

10

, 10

7

12

12

10

11

IN TH E

Su prem e Court of tfjc Unite!) S ta te s!

O c to be r T e r m , 1970

St a te o f A la b a m a , M a cD o n a ld G a l l io n

As Attorney General, State of Alabama,

Appellant,

v.

U n it e d St a t e s o f A m er ic a , C h a r le s

S. W h it e -Sp u n n e r , as United States

District Attorney, O l l ie M ae D avis

as Mother and next friend of B e t t y

A n n D avis, and J a m es A l l e n D avis,

J erris L eo n a rd , as Chief of Civil

Rights Division, Department of Justice,

and R o be r t H . F in c h , as Secretary of

Health, Education and Welfare, and

B irdie M ae D avis,

Appellees.

JU RISD ICTIO N AL STATEM ENT

STATEM ENT AS TO JU RISD ICTIO N

̂ The appellants, pursuant to United States Supreme

Court Rules 13(2) and 15, file this their statement

of the basis upon which it is contended that the Su

preme Court of the United States has jurisdiction on a

direct appeal to review the final decree and order in

question, and upon which it is contended that the Su

preme Court should exercise such jurisdiction in this

case.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

On June 26, 1970, the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama issued an opinion

declaring the provisions of Section 2, Act No. 1, Special

Session of the 1970 Alabama Legislature, to be uncon

stitutional. The district court also entered an order dis

missing the complaint of the State of Alabama, which

sought to determine the application and constitutional

validity of the Act. The order and opinion of the

district court appear as "Appendix A ” , Appendices to

the Jurisdictional Statement. The Act in question, the

text of which is set forth in full on pages 3 and 4 of

the Jurisdictional Statement, deals with the operation

and desegregation of the public schools throughout the

State of Alabama. Section 2 of the Act is specifically

directed to racial balance in public schools.

On March 10, 1970, in a sequel to the instant case,

the plaintiffs in the case of Birdie Mae Davis, et al. v.

Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

Civil Action No. 3003-63, United States District

Court, Southern District of Alabama, attacked the

constitutional validity of the same legislative act as

here in question.1 The United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama, on March 16,

1970, dismissed the petition whereby the Act was

questioned and held that the case of Birdie Mae Davis

v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

supra, was "not the proper vehicle in which to test the

constitutionality of said act.” This March 16, 1970,

opinion and order of the District Court appears as

1. A supplemental complaint was filed in Civil Action No.

3003-63, United States District Court, Southern District of Ala

bama, whereby the plantiffs there allege the act to be "patently

unconstitutional” and sought declaratory and injunctive relief.

3

"Appendix B,” Appendices to the Jurisdictional State

ment.

TH E A CT IN QUESTION

Act No. 1, Special Session of the Alabama Legisla

ture 1970, approved March 4, 1970, provides as fol

lows:

"Enrolled, AN ACT, TO PREVENT DISCRIMINA

TION ON ACCOUNT OF RACE, COLOR, CREED

OR NATIONAL ORIGIN IN CONNECTION WITH

THE EDUCATION OF THE CHILDREN OF THE

STATE OF ALABAMA. BE IT ENACTED BY THE

LEGISLATURE OF ALABAMA: Section 1. No person

shall be refused admission into or be excluded from any

public school in the State of Alabama on account of race,

creed, color or national origin. Section 2. No student

shall be assigned or compelled to attend any school on

account of race, creed, color or national origin, or for

the purpose of achieving equality in attendance or in

creased attendance or reduced attendance, at any school,

of persons of one or more particular races, creeds,

colors or national origins; and no school district, school

zone or attendance unit, by whatever name known, shall

be established, re-organized or maintained for any such

purpose, provided that nothing contained in this section

shall prevent the assignment of a pupil in the manner

requested or authorized by his parents or guardian, and

further provided that nothing in this section shall be

deemed to affect, in any way, the right of a religious

or denominational educational institution to select its

pupils exclusively or primarily from members of such

religion or denomination or from giving preference to

such selection to such members or to make such selection

to its pupils as is calculated to promote the religious

principle for which it is established. Section 3. The pro

visions of this Act are severable. If any part of the Act

is declared invalid or unconstitutional, such declaration

shall not affect the part which remains. Section 4. All

laws and parts of laws in conflict herewith are hereby

repealed. Section 5. This Act shall become effective

upon its passage and approval by the Governor, or upon

its otherwise becoming a law.”

4

JURISDICTIO N

This action was initiated by the filing of a complaint

for a declaratory judgment as provided in 28 U. S. C.

A. Sections 2201 and 2202, seeking declaratory and

injunctive relief. The defendants below are either

plaintiffs in the suit of Birdie Mae Davis, et al. v.

Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

Alabama, which suit was pending in the District Court

below as Case No. 3003-63, or are officers or attor

neys of the United States of America who were parti

cipating in that litigation. The action below sought to

establish the constitutionality of Alabama Act No. 1,

supra, and to enjoin the defendants from taking official

action contrary thereto.

The jurisdiction of the District Court to entertain

the cause was predicated on 28 U. S. C. A. Sections

1361 and 1442.

A district court of three judges was convened by

order of the Chief Judge of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit at the request of the

District Judge before whom the action was originally

filed.

On June 26, 1970, the three judge court held Sec

tion 2 of Alabama Act No. 1, supra, to be unconstitu

tional and that a three judge court was not required

under 28 U. S. C. A. Section 2281. The case was then

remanded for action by a single district judge with the

express provision that the judgment of the district

judge ^uo^dd become final when joined through con

currence or dissent by the other members of the panel.

On the same day, June 26, 1970, the single district

judge did dismiss the complaint and the other mem

bers of the panel did concur at that time.

5

The finality of the decree below therefore directly

stems from the order and concurrence of the three

judge court.

Appellants filed their notice of appeal to the Su

preme Court of the United States on July 23, 1970,

with the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Alabama.2

Appellants believe that 28 U. S. C. A. Section 1253,

confers jurisdiction of this appeal to this Court. The

District Court’s order of June 26, 1970, was made

final by the concurrence of the three judge court and

had the effect of declaring the State statute involved

to be unconstitutional.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the district court erred in holding that

Section 2 of Act No. 1, Special Session of the Alabama

Legislature 1970, is unconstitutional as being in con

flict with an order of a federal court, acting under the

Fourteenth Amendment?

2. Whether a state legislative act, operative in a

state wherein unitary school systems have been

achieved, may constitutionally provide that no student

shall be assigned or compelled to attend any school on

account of race or color for the purpose of achieving a

racial balance?

2. In accord with the suggestion of the three judge court, ap

pellants on July 23, 1970, filed a simultaneous appeal to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, the per

fecting of which has been stayed, on motion of the appellants,

pending a determination and disposition of the appeal in this

Court.

6

STATEM EN T OF TH E CASE

The statute which forms the basis of these proceed

ings was enacted during March of 1970 by the Legis

lature of the State of Alabama and became effective

on March 4, 1970. This act is directly concerned with

the desegregation of Alabama public schools and speci

fically states that the purpose of the legislation is to

"prevent discrimination on account of race, color,

creed or national origin in connection with the educa

tion of the children of the State of Alabama.”

Shortly after passage, the constitutionality of the

act was challenged in United States District Court for

the Southern District of Alabama in the case of Davis

v. School Commissioners of Mobile County, Alabama.

The district court at that time held that Davis, supra,

was not the proper vehicle to test the constitutionality

of the Act. (See "Appendix B,” Appendices to the

Jurisdictional Statement).

The complaint in the instant case which was filed

on March 26, 1970, by the Attorney General of the

State of Alabama, alleged that Act No. 1, supra, is

constitutional. The complaint further alleged that the

defendants below claim the Act to be unconstitutional

and that the defendant, United States Officials, were

in fact acting in direct conflict with this provision by

submitting plans for the desegregation of the public

schools in Alabama which go far beyond the require

ments of the United States Constitution.

It is important to note that at the time of the passage

of the above legislation by the Legislature of the State

of Alabama, every school in the State of Alabama was

under a court order expressly and specifically directing

the establishment of unitary school systems. These

7

cases, which involve each of the State’s 119 school

districts, are listed in "Appendix C ” Appendices to

the Jurisdictional Statement.

The Court below recognized that Section 2 of the

Act presented the only constitutional question. The

District Court held this Section to be unconstitutional

as "purporting to make school administrators neutral

on the question of desegregation” and limiting "their

tools for the accomplishment of this constitutional

obligation to 'freedom of choice’ plans.”

TH E QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE

SUBSTANTIAL

The Supreme Court of the United States on March

9, 1970, in the case of Northcross v. Board of Educa

tion of the City of Memphis, 397 U. S. 232, 90 S. Ct.

891, 25 L.Ed. 2d 246, (concurring opinion by the

Chief Justice) held the following to be basic practical

problems which should be resolved as soon as possible:

. . whether, as a constitutional matter, any particular

racial balance must be achieved in the schools; to what

extent school districts and zones may or must be altered

as a constitutional matter; to what extent transporta

tion may or must be provided to achieve the ends sought

by prior holdings of the court.”

The Alabama Act now before this Court squarely

presents the questions as to whether racial balance may

or must be constitutionally required in public educa

tion as well as the constitutionality and permissibility

of creating or altering attendance zones for such pur

poses. The provisions of Act No. 1, supra, which were

held unconstitutional by the District Court, reflect

the understanding of the State of Alabama as to what

the Constitution of the United States and the prior

orders of this Court properly require. This under

standing is not without studied analysis and sound

foundation. Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education, 396 U. S. 19, 90 S. Ct. 29, 24 L.Ed. 2d 19;

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U. S. 430, 20 L.Ed. 2d 716, 88 S. Ct. 1689.

Section 2 of the Alabama Act provides first that no

student shall be assigned or compelled to attend any

school on account of race or color for the purpose of

achieving a racial balance. We earnestly submit that

this provision is but the logical, inescapable and con

stitutional converse of holding that a child shall not

be excluded from any school because of race or color.

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

supra.

The Supreme Court of the United States has writ

ten that unitary school systems must be achieved

throughout the nation. Each and every school district

in the State of Alabama, as previously noted, is under

an express and direct judicial mandate to accomplish

unitary systems. When public school desegregation

reaches this point, this Court has never held that racial

balance or racial ratios in student attendance must be

maintained through the compulsory assignment of

students.

The concept of de jure segregation is not now appli

cable to this State. No possible constitutional justifica

tion can now be offered for requiring racial balance in

Alabama as distinguished from states such as Illinois,

Pennsylvania, Missouri or Michigan, wherein over

45% of the Negro school students attend virtually "all

Negro schools, (95% to 100% N egro).” 3

3. Report of the Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare, January 4, 1970, Table 1-A thereof.

9

No possible constitutional justification can now be

offered for treating school systems in Alabama dif

ferently or for treating them more stringently than

systems in such cities as Chicago, Illinois, where 85.4

of the Negro students attend virtually all Negro

schools; or in Buffalo, New York, where 61.1 of the

Negro students attend virtually all Negro schools; or

in St. Louis, Missouri, where 86.2 of the Negro students

are attending virtually all Negro schools. These are

but examples of the prevailing conditions which exist

throughout the ''nonsouthern states.” 4

Racial balance through the compulsory assignment

of students has not been constitutionally required in

the above states, nor has such been required in many

similar school districts throughout the United States

as reflected in the Health, Education and Welfare re

port noted above.

The first sentence of Section 2 of the Alabama Act

to the effect that forced assignment of students is not

to be utilized to achieve racial balance is consistent,

therefore, with the manner in which the Constitution

of the United States is being applied to other states.

The provisions contained in Section 2 of the Ala

bama Act which hold that school districts, school

zones, or attendance areas shall not be "established, re

organized or maintained” for the purpose of maintain-

4. Report of the Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare, January 4, 1970— Table 1-A thereof. This report addition

ally shows that many school systems located outside the Southern

States are maintaining "all Negro schools,”—for example, Chicago,

Illinois has 208 schools with 99% to 100% Negro enrollment;

New York City has 114 such schools; Detroit, Michigan has 67

such schools and Baltimore, Maryland, has 89 such "all Negro

schools.”

10

ing a racial balance similarly reflect the understanding

of the Alabama Legislature as to the constitutional re

quirements as set forth by prior holdings of this Court.

This understanding is also supported by a studied

analysis of the constitutional principles involved.

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

supra; Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F.

2d 1387 (6 Cir. 1969); Green v. County School

Board of New Kent County, supra.

The district court was incorrect in its opinion that

Section 2 of the Alabama Act "purports to make

school administrators neutral on the question of dese

gregation and limits their tools for the accomplishment

of this constitutional obligation to 'freedom of choice’

plans.”

The provisions of Section 2 of the Alabama Act to

the effect that nothing in the Act shall prevent the

assignment of pupils in the manner requested by

parents of the students does not require the assign

ments but only insures that such may be made. School

Boards in Alabama, under this Act, are free, therefore,

to comply with their constitutional duty of school

desegregation by any effective means, including,

where appropriate, the granting of requests by parents

or guardians. (See Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 312 F. Supp. 503 (D. C. N. C.

1970).

The intent of the Alabama Act was and is to remove

racial consciousness in the assignment of public school

children throughout the State of Alabama, upon the

achievement of unitary school systems. The Act fol

lows the only logical, legal and fair interpretation of

the Constitution of the United States. The Act follows

the spirit of Brown I, Brown II, and Green, in prevent-

11

ing racial discrimination in public schools. Act No. 1,

supra, simply states that upon the concept of de jure

segregation becoming inapplicable to the State of Ala

bama, the school children of this state, Negro and

white alike, and their parents, should be given the same

treatment and should be afforded the same rights as

are children and parents throughout the nation.

The definite, real, substantial and concrete contro

versy existing between the parties stems from the fol

lowing factors:

1. The continuing insistence by the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare through the defend

ants, Jerris Leonard and Charles White-Spunner, act

ing in consort, that racial balance and/or student

ratios are constitutionally required to desegregate the

public schools throughout this state (See opinion of

District Court in Carr v. Montgomery County Board

of Education, February 25, 1970, Civil Action No.

2072-N ), wherein the Court stated "Plaintiffs’ objec

tions and the few proposals made by the Office of

Education, Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare, that differs from the plan as proposed by the

Montgomery County Board of Education appear to

be based upon a theory that racial balance and/or

student ratios as opposed to the complete disestablish

ment of a dual school system is required by the law.”

2. The position taken by the plantiffs in Davis v.

School Commissioners of Mobile County, supra, that

Act No. 1, which they designate as the "freedom of

choice act,” is patently unconstitutional as applied to

them. (Supplemental complaint filed by such plain

tiffs on March 10, 1970, in Civil Action No. 3003-63,

P - 4 ) .

12

3. The position of the State of Alabama that the

provisions of Act No. 1, supra, are entirely constitu

tional and in strict accord with the provisions of the

United States Constitution and the applicable decisions

of the United States Supreme Court.

4. The solemn responsibility of the State of Ala

bama through Governor Albert P. Brewer and through

the Attorney General of the State of Alabama to in

sure that all constitutional legislative provisions of the

State be followed and enforced throughout the State of

Alabama.

A complaint which presents a definite and concrete

controversy, touching the legal relations of parties

having adverse legal interests properly presents a case

for declaratory relief. Public Service Commission of

Utah v. Wycoff Co., 344 U. S. 237, 73 S. Ct. 236,

97 L. Ed. 291; Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. HaTvorth,

300 U. S. 227, 57 S. Ct. 461, 81 L. Ed. 617; Public

Utilities Com. v. U. S., 355 U. S. 534, 2 L. Ed. 2d 470,

78 S. Ct. 446.

CO NCLUSION

The issues presented by this appeal are of vital con

cern to every citizen of the State of Alabama. The

public school system of education has become one of

the cornerstones of our democratic society and a

vehicle whereby every child is afforded an opportunity

to learn and to advance intellectually, all of which

inures to the benefit of our entire country. The

district court’s ruling has the effect of substituting its

judgment for that of the legislature of the State of

Alabama in a matter which affects all school age chil

dren in the State. A unitary school system is in opera

tion throughout the State pursuant to federal court

13

order. The Act in question does no more than guar

antee that no child shall be excluded from any public

school on account of race, creed, color or national

origin. The Act does nothing to perpetuate a dual

system of schools, or a policy of segregation whether

de jure or de facto.

The district court’s ruling that Act No. 1, Special

Session of the Alabama Legislature 1970, assumes the

Fourteenth Amendment requires that racial balance or

racial ratios in student attendance must be maintained

through the compulsory assignment of students.

Appellants submit that this appeal presents sub

stantial federal questions which require briefs on the

merits and oral argument for their resolution.

Respectfully submitted,

J o se p h D. Ph e l p s

Special Assistant Attorney General

APPENDICES

14

APPENDIX A

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA,

SOUTHERN DIVISION

STATE OF ALABAMA,

MacDONALD GALLION as Attorney

General, State of Alabama,

Plantiffs,

versus

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

CHARLES S. WHITE-SPUNNER, as

United States District Attorney,

OLLIE MAE DAVIS, as Mother and

next friend of BETTY A N N DAVIS,

and JAMES ALLEN DAVIS, JERRIS

LEONARD, as Chief of Civil Rights

Division, Department of Justice and

ROBERT H. FINCH, as Secretary of

Health, Education and Welfare, and

BIRDIE MAE DAVIS,

Defendants.

Before GEWIN, Circuit Judge, and THOMAS and PITTMAN,

District Judges.

PER CURIAM:

A 1970 Special Session of the Alabama Legislature enacted a

statute entitled, "An Act, To Prevent Discrimination on Account

of Race, Creed or National Origin in Connection with the Educa

tion of the Children of the State of Alabama.” 1 This Act was

approved by the Governor of Alabama on March 4, 1970. In the

present action the State of Alabama seeks a declaration that this

enactment is constitutional. It also seeks to have this court modify

prior judgments to conform to the strictures of this legislation, and

to enjoin certain federal officers to conform their actions to its

provisions.

The defendants in the present action are the parties plantiff

in Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 5935-70-P.

1. The Text of the statute is quoted infra.

15

Alabama, S. D. Ala., Civil No. 3003-63, and certain officers of

the United States. On 31 January 1970, this court entered an

order in the Davis case requiring forthwith implementation of a

desegregation plan for the Mobile schools. Following the adoption

of the Act in question, the Board of School Commissioners by

resolution instructed the school superintendent and staff to abide

by the Act and to take no further steps in implementing the court-

approved plan. The plantiffs in the Davis case then sought leave to

add the Governor and Attorney General of Alabama as parties

defendant and to amend their complaint to seek a declaration that

the subject Act is unconstitutional and an injunction against com

pliance with it.

Following a hearing, this court denied the plantiff’s motion.

In his order Judge Thomas, discussing the subject Act, stated:

In 1809, Chief Justice Marshall said: " I f the legislators

of the several states may, at will, annul the judgments

of the Courts of the United States, and destroy the rights

acquired under those judgments, the Constitution itself

becomes a solemn mockery; and the nation is deprived of

the means of enforcing its laws by the instrumentality

of its own tribunals.”

The School Board is required to follow the order of this

Court of January 31, 1970, as amended, and if the same

is not followed within three days from this date, a fine

of $1,000 per day is hereby assessed for each such day,

against each member of the Board of School Commis

sioners.

The plaintiffs in this case, on the 10th day of May 1970,

filed a petition requesting this Court to declare the

Freedom of Choice Act of the Legislature of the State of

Alabama unconstitutional. This case is not the proper

vehicle in which to test the constitutionality of said Act.

The said petition is therefore dismissed.

The State of Alabama through its Attorney General then

instituted the present action joining as defendants the plaintiffs in

the Davis case, the Chief of the Civil Rights Division of the Justice

Department, Charles S. White-Spunner, as United States District

Attorney, and the Secretary of Health, Education and Wel

fare. The present three-judge court was constituted by the

Chief Judge of this circuit pursuant to the request of Judge Pitt-

16

man, before whom this action was originally filed. In his order

designating the panel, the Chief Judge states:

This designation and composition of the three-

judge court is not a prejudgment, express or implied, as

to whether this is properly a case for a three-judge rather

than a one-judge court. This is a matter best determined

by the Three-Judge Court as this enables a simultaneous

appeal to the Court of Appeals and to the Supreme Court

without delay, awkwardness, and administrative insuffi

ciency of a proceeding by way of mandamus from either

the Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court, or both, di

rected against the Chief Judge of the Circuit, the presid

ing District Judge, or both.

In California Water Service Co. v. Redding,2 the Supreme

Court observed that the statutory requirement of a three-judge

court is not applicable unless the constitutional claim regarding a

state statute or administrative order is substantial. The Court then

stated: "It is therefore the duty of a district judge, to whom an

application is made for an injunction restraining the enforcement

of a state statute or order is made, to scrutinize the bill of com

plaint to ascertain whether a substantial federal question is pre

sented. . . .” 3 While "[theoretically, this solo travail should be the

indispensable first step,” 4 such a procedure has often led to the im

penetrable judicial snarl described in Jackson v. Choate,5 Accord

ingly, it is now the preferred practice in the Fifth Circuit, in all

but exceptional cases, to initially constitute the three-judge court

and allow it to determine the issue of substantuality and the other

issues in the case.6 The procedure, envisioned in Jackson, tends

to assure that the decision by the district court will be the final

trial court action in the case. Regardless of the proper appellate

course, the Court of Appeals or the Supreme Court will have the

entire case for determination.7

2. 304 U. S. 252 (1938). See Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 7 (1962).

3. 304 U. S. at 254.

4. Jackson v. Choate, 404 F. 2d 910, 912 (5th Cir. 1968).

5. 404 F. 2d 910 (5th Cir. 1968).

6. Id.

7. See Hargrove v. McKinney, 302 F. Supp. 1381 (M. D. Fla. 1969);

Rodriguez v. Brown, 299 F. Supp. 479 (W. D. Tex. 1969).

17

In light of this procedure, the duty, described in Redding,

to determine the substantiality of the federal question devolves

upon the present panel. It is an elementary principle of law that

a federal court has jurisdiction of a case, initially, to determine

whether it has jurisdiction to ultimately decide the merits of the

case.8 As Chief Judge Brown observed in Jackson, "Frequently in

resolving the threshold issue of substantiality—i.e., the need for

a 3-Judge Court—the Court has to go to the very merits of the

case.” 9 Such is the case here. After a careful study of the com

plaint and following a hearing on the question, we are of the

unanimous opinion that the State of Alabama’s claim does not

present a substantial federal question inasmuch as it is foreclosed

by prior decisions of the United States Supreme Court.10

The Act in question provides:

Enrolled, An Act, TO PREVENT DISCRIMINATION

ON ACCOUNT OF RACE, COLOR, CREED OR

NATIONAL ORIGIN IN CONNECTION WITH

THE EDUCATION OF THE CHILDREN OF THE

STATE OF ALABAMA. BE IT ENACTED BY THE

LEGISLATURE OF ALABAMA: Section 1. No person

shall be refused admission into or be excluded from any

public school in the State of Alabama on account of race,

creed, color or national origin. Section 2. No student

shall be assigned or compelled to attend any school on

account of race, creed, color or national origin, or for

the purpose of achieving equality in attendance or in

creased attendance or reduced attendance, at any school,

of persons of one or more particular races, creeds, colors

or national origins; and no school district, school zone or

attendance unit, by whatever name known, shall be es

tablished, re-organized or maintained for any such pur

pose, provided that nothing contained in this section shall

prevent the assignment of a pupil in the manner re

quested or authorized by his parents or guardian, and

further provided that nothing in this section shall be

deemed to affect, in any way, the right of a religious or

denominational educational institution to select its pupils

8. C. Wright, Federal Courts § 16 at 50-55 (2d ed. 1970).

9. 404 F. 2d at 913.

10. Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 7 (1962); California Water Service Co.

v. Redding, 304 U. S. 252 (1938); Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (5th Cir.

1963).

18

exclusively or primarily from members of such religion

or denomination or from giving preference to such selec

tion to such members or to make such selection to its

pupils as is calculated to promote the religious principle

for which it is established. Section 3. The provisions of

this Act are severable. If any part of the Act is declared

invalid or unconstitutional, such declaration shall not

affect the part which remains. Section 4. All laws and

parts of laws in conflict herewith are hereby repealed.

Section 5. This Act shall become effective upon its pass

age and approval by the Governor, or upon its otherwise

becoming a law.

The constitutional question involves only Section 2 of the

Act. This section purports to make school administrators neutral

on the question of desegregation and limits their tools for the

accomplishment of this constitutional obligation to "freedom-of-

choice” plans. It is clear, indeed, it is insisted by the State of Ala

bama, that such a limitation is in direct conflict wth numerous

desegregation plans approved and ordered by federal courts

throughout Alabama.11

An unwaivering line of Supreme Court decisions make it clear

that more than administrative neutrality is constitutionally re

quired. "Under explicit holdings of this Court the obligation of

every school district is to terminate dual school systems at once

and to operate now and hereafter only unitary schools. Griffin

v. School Board, 377 U. S. 218, 234, 12 L. Ed. 2d 256, 267, 84 S.

Ct. 1226 (1964); Green v. County School Board of Kent County,

11. Paragraph VI of the complaint provides:

It is further alleged by plantiffs that the said Act if constitutional

is required to be followed and applied by all courts, state and federal;

that where conflict exists between prior orders of any court and the

Act the orders should be amended or modified to conform to the

provisions of the state law.

The prayer for relief contains the following:

2. By way of supplemental relief, if the said Act is decreed to

be constitutional, that this court modify or amend every prior order

relating to the public schools issued by it so as to make the orders

conform to and not conflict with the provisions of Act No. 1.

5. That defendants Jerris Leonard, as Chief of the Civil Rights

Division, be ordered by this court to follow the provisions of said

Act No. 1 in all future cases involving the desegregation of the public

schools in Alabama and to apply to all courts in Alabama in which

he has appeared for modification of prior decrees which now conflict

with the provisions of Act No. 1.

19

391 U. S. 430, 438-439, 442, 20 L. Ed. 2d 716, 723, 724, 726, 88

S. Ct. 1689 (1968).” 12 Neither are "freedom-of-choice” plans

the optimum tool for the accomplishment of this obligation. In

Green v. County School Bd.13 the Court held such a plan insuffi

cient, stating, " if there are reasonably available other ways, such

for illustration as zoning,14 promising speedier and more effective

conversion to a unitary, non-racial school system, 'freedom-of-

choice’ must be held unacceptable.” 16

The settled state of the law convinces us that there is no

substantial federal question presented in this case. Where Section

2 of the subject Act conflicts with an order of a federal court

drawing its authority from the Fourteenth amendment, the Act

is unconstitutional and must fail. The supremacy clause of our

compact of government will admit to no other result. Indeed

this has already been the result in cases where this and similar

legislation has been asserted as a bar to constitutional obligations.16

12. Alexander v. Holmes Co. Bd. of Ed., 396 U. S. 19 (1969). See United

States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F. 2d 836, 845-46 (5th

Cir. 1966), aff’d reh. en banc, 380 F. 2d 385, cert, denied, 389 U. S. 840

(1967).

13. 391 U. S. 430 (1968).

14. The subject Act expressly prohibits zoning.

15. Id. at 441.

16. A Three-Judge Court in the Middle District of Alabama in Lee, et al v.

Macon Co. Bd. of Ed., Civ. No. 604-E, on three occasions following passage

of the Act, refused to modify prior orders to allow the school boards involved

to continue to operate under Freedom of Choice: Tuscumbia City Board, order

dated March 12, 1970; Colbert County System, order dated March 16, 1970;

Monroe County System, order dated March 23, 1970.

In Swain v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., et al., (W. D. N. C,, No.

1974, April 29, 1970), a three-judge court held provisions of an analagous

North Carolina law unconstitutional insofar as it interfered with the school

board’s duty to establish a unitary school system.

In Bivins v. Bibb Co. Bd. of Ed. (M. D. Ga. No. 1926, May 22, 1970) the

district court enjoined an action in state court which sought an injunction

requiring the local board to comply with a similar Georgia statute.

20

We are also of the unanimous opinion that a three-judge court

is not required for the present action under 28 U. S. C. § 2281.17

However, we are mindful that the question presented is important

throughout the State of Alabama. Moreover, the ultimate disposi

tion of this case on appeal should be free from unnecessary delay in

order to minimize any disruptive effect on the upcoming school

year.

Out of an abundance of caution, against the possibility that

this case might fall upon the snares described in Jackson v. Choate,

we remand the case for action by a single district judge. The judg

ment of the district court will become final when joined, through

concurrence or dissent, by the other members of the present panel.

This assures that, in the event of an appeal, the appropriate appel

late court, whether the Court of Appeals or the Supreme Court,

will have the entire case for decision.18

Done at Mobile, Alabama this the 26 day of June 1970.

WALTER GEWIN,

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT JUDGE

DANIEL H. THOMAS,

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

VIRGIL PITTMAN,

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

17. 28 U. S. C. § 2281, provides for a three-judge court where the plaintiff

seeks, "An interlocutory or permanent injunction restraining the enforce

ment, operation or execution of any State statute by restraining the action

of any officer of such State in the enforcement or execution of such statute

. . . upon the ground of the unconstitutionality of such statute . . . .” It is a

technical statute to be strictly construed. Phillips v. United States, 312 U. S.

246 (1948); C. Wright, Federal Courts § 50 at 189 (2d ed. 1970). For 2281

to apply a state statute must be challenged on constitutional grounds in an

action in which injunctive relief is sought against a state officer who is a party

defendant. C. Wright, supra. The only state officer involved in the instant

case is a party plantiff seeking to uphold the constitutionality of the state

statute involved. The injunctive relief requested would operate against officers

of the federal government. Inasmuch as the injunctive relief requested against

the federal officers is not related to a constitutional attack on any federal

statute, a three-judge court is not required by 28 U. S. C. § 2282.

18. Rodriguez v. Brown, 299 F. Supp. 479 (W. D. Tex. 1969). See Har

grove v. McKinney, 302 F. Supp. 1381 (M. D. Fla. 1969); Jackson v. Choate

404 F. 2d 910 (5th Cir. 1968).

21

IN TH E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA,

SOUTHERN DIVISION

STATE OF ALABAMA,

MacDONALD GALLION as Attorney

General, State of Alabama,

Plantiffs,

versus

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

CHARI.ES S. WHITE-SPUNNER, as

United States District Attorney,

OLLIE MAE DAVIS, as Mother and

next friend of BETTY ANN DAVIS,

and JAMES ALLEN DAVIS, JERRIS

LEONARD, as Chief of Civil Rights

Division, Department of Justice and

ROBERT H. FINCH, as Secretary of

Health, Education and Welfare, and

BIRDIE MAE DAVIS,

Defendants.

ORDER OF DISMISSAL

PITTMAN, District Judge:

For the reasons stated in the opinion of the three-judge panel

remanding the present case to a single judge,1 the same is hereby

dismissed.

GEWIN, Circuit Judge, and THOMAS, District Judge, con

cur in this order.2

Done at Mobile, Alabama this 26 day of June, 1970.

WALTER GEWIN,

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT JUDGE

DANIEL H. THOMAS,

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

VIRGIL PITTMAN,

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 5935-70-P.

1. Opinion of Judges Gewin, Thomas, and Pittman, dated June 26'th, 1970.

2. See note 18 and accompanying text of the three-judge opinion.

22

APPENDIX B

IN TH E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUHERN DIVISION

BIRDIE MAE DAVIS, Et Al,

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

by RAMSEY CLARK, Attorney

General of the United States,

Plaintiff -Intervenor,

CIVIL ACTION

vs.

BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMISSION- NO. 3003-63

ERS OF MOBILE COUNTY, Et Al,

Defendants

and

TWILA FRAZIER, Et Al,

Defendant-lntervenors.

On January 14, 1970, the Supreme Court of the United

States reversed this case and the Fifth Circuit on January 21st,

ordered this Court to enter its plan for implementation on Febru

ary 1, 1970. This Court entered its decree on January 31, 1970,

and ordered that it be implemented forthwith. The Board of

School Commissioners announced that it would be implemented

on March 16, 1970, today.

The Legislature of Alabama passed the Freedom of Choice

Bill on the 4th day of March 1970. The School Board then passed

a resolution to the effect that it would not follow this Court’s

decree but would continue to operate as it has heretofore.

In 1809, Chief Justice Marshall said: " I f the legislators of

the several states may, at will, annul the judgments of the Courts

of the United States, and destroy the rights acquired under those

judgments, the Constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery; and

the nation is deprived of the means of enforcing its laws by the

instrumentality of its own tribunals.”

The School Board is required to follow the order of this Court

of January 31, 1970, as amended, and if the same is not followed

23

within three days from this date, a fine of $1,000 per day is hereby

assessed for each such day, against each member of the Board of

School Commissioners.

The plantiffs in this case, on the 10th day of March 1970,

filed a petition requesting this Court to declare the Freedom of

Choice Act of the Legislature of the State of Alabama unconstitu

tional. This case is not the proper vehicle in which to test the

constitutionality of said Act. The said petition is therefore dis

missed.

DONE at Mobile, Alabama, this the 16th day of March 1970.

DANIEL H. TLIOMAS

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

U. S. DISTRICT COURT

SOU. DIST. ALA.

FILED AND ENTERED THIS THE

............DAY OF MARCH 1970.

MINUTE ENTRY N O ......................

WILLIAM J. O’CONNOR, Clerk

BY...............................................................

Deputy Clerk

24

APPENDIX C

COURT ORDERS PURSUANT TO WHICH

ALABAMA SCHOOLS ARE OPERATING

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

Brown v. Board of Education of City of Bessemer

C. A. No. 65-366

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education

C. A. No. 65-396

Boykins v. Board of Education of City of Fairfield

C. A. No. 65-499

Armstrong v. Board of Education of City of Birmingham

C. A. No. 9678

Bennett v. Madison County Board of Education

C. A. No. 63-613

Hereford v. Board of Education of City of Huntsville

C. A. No. 63-109

Horton v. Lawrence County Board of Education

C. A. No..........................

Miller v. Board of Education of City of Gadsden

C. A. No. 63-547

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

United States v. Lowndes County Board of Education

C. A. No. 2328-N

Harris v. Crenshaw County Board of Education

C. A. No. 2455-N

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education

C. A. No. 2072-N

Harris v. Bullock County Board of Education

C. A. No. 2073-N

Franklin v. Barbour County, Ala., Board of Education

C. A. No. 2458-N

25

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

United States v. Wilcox County Board of Education

C. A. No. 3934-65

United States v. Hale County Board of Education

C. A. No. 3980-66

United States v. Perry County Board of Education

C. A. No. 4222-66

United States v. Choctaw County Board of Education

C. A. No. 4246-66

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County

C. A. No. 3003-63

STATEWIDE (MIDDLE DISTRICT)

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education

C. A. No. 604-E