Robertson v Wegmann Certiorari

Public Court Documents

May 31, 1978

22 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Robertson v Wegmann Certiorari, 1978. fd22e392-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/37cc210e-2d46-43d1-82a0-05750580c543/robertson-v-wegmann-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

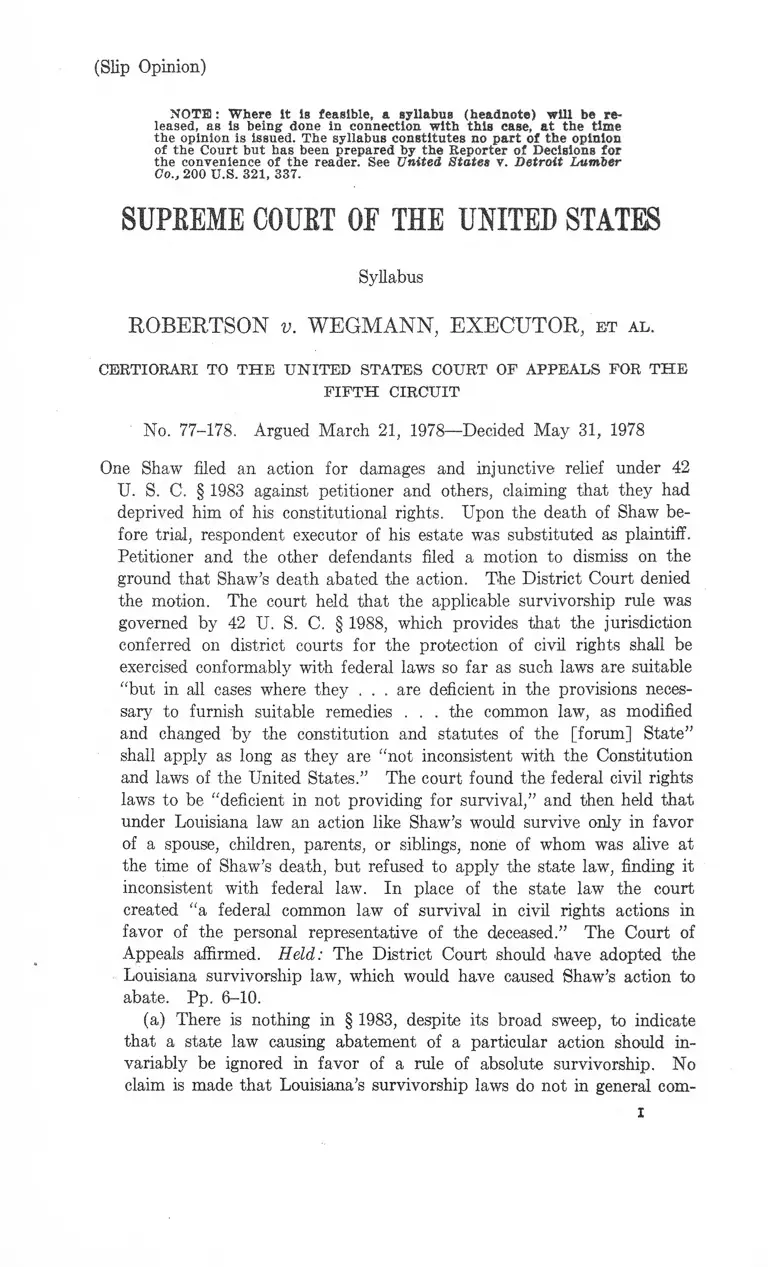

(Slip Opinion)

NOTH: Where It Is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be re-

leased, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time

the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion

of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for

the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Lumber

Co., 200 U.S. 321, 337.

SUPBEME COUBT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN, EXECUTOR, et a l .

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-178. Argued March 21, 1978—Decided May 31, 1978

One Shaw filed an action for damages and injunctive relief under 42

TJ. S. C. § 1983 against petitioner and others, claiming that they had

deprived him of his constitutional rights. Upon the death of Shaw be

fore trial, respondent executor of his estate was substituted as plaintiff.

Petitioner and the other defendants filed a motion to dismiss on the

ground that Shaw’s death abated the action. The District Court denied

the motion. The court held that the applicable survivorship rule was

governed by 42 U. S. C. § 1988, which provides that the jurisdiction

conferred on district courts for the protection of civil rights shall be

exercised conformably with federal laws so far as such laws are suitable

“but in all cases where they . . . are deficient in the provisions neces

sary to furnish suitable remedies . . . the common law, as modified

and changed by the constitution and statutes of the [forum] State”

shall apply as long as they are “not inconsistent with the Constitution

and laws of the United States.” The court found the federal civil rights

laws to be “ deficient in not providing for survival,” and then held that

under Louisiana law an action like Shaw’s would survive only in favor

of a spouse, children, parents, or siblings, none of whom was alive at

the time of Shaw’s death, but refused to apply the state law, finding it

inconsistent with federal law. In place of the state law the court

created "a federal common law of survival in civil rights actions in

favor of the personal representative of the deceased.” The Court of

Appeals affirmed. Held: The District Court should have adopted the

Louisiana survivorship law, which would have caused Shaw’s action to

abate. Pp. 6-10.

(a) There is nothing in § 1983, despite its broad sweep, to indicate

that a state law causing abatement of a particular action should in

variably be ignored in favor of a rule of absolute survivorship. No

claim is made that Louisiana’s survivorship laws do not in general com-

x

II ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

Syllabus

port with the underlying policies of § 1983 or that Louisiana’s decision

to restrict certain survivorship rights to the relations specified above is

unreasonable. Pp. 6-7.

(b) The goal of compensating those injured by a deprivation of rights

provides no basis for requiring compensation of one who is merely suing

as decedent’s executor. And, given that most Louisiana actions survive

the plaintiff’s death, the fact that a particular action might abate would

not adversely affect § 1983’s role in preventing official illegality, at least

in situations such as the one here where there is no claim that the

illegality caused plaintiff’s death. P. 8.

545 F. 2d 980, reversed.

M a r sh all , J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which B urger,

C. J., and Stew art , P ow ell , R e h n q u ist , and Steven s , JJ., joined.

B l a c k m u n ,, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which B r e n n a n and W h it e ,

JJ., joined.

NOTICE : This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication

in the preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are re

quested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the

United States, Washington, D.C. 20543, of any typographical or other

formal errors, in order that corrections may be made before the pre

liminary print goes to press.

SUPKEME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 77-178

Willard E. Robertson, Petitioner,

v.

Edward F. Wegmann, Executor of

the Estate of Clay L. Shaw,

et a!.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit.

[M ay 31, 1978]

M r . J u s t ic e M a r s h a l l delivered the opinion of the Court.

In early 1970, Clay L. Shaw filed a civil rights action under

42 U. S. C. § 1983 in the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana. Four years later, before trial

had commenced, Shaw died. The question presented is

whether the District Court was required to adopt as federal

law a Louisiana survivorship statute, which would have caused

this action to abate, or was free instead to create a federal

common-law rule allowing the action to survive. Resolution

of this question turns on whether the state statute is “ incon

sistent with the Constitution and laws of the United States.”

42 U. S. § 1988.1 1

1 Title 42 U. S. C. § 1988 provides in pertinent part:

“The jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters conferred on the district

courts by the provisions of this chapter and Title 18, for the protection

of all persons in the United States in their civil righte, and for their vin

dication, shall be exercised and enforced in conformity with the laws of

the United States, so far as such laws are suitable to carry the same into

effect; but hi all cases where they are not adapted to the object, or are

deficient in the provisions necessary to furnish suitable remedies and

punish offenses against law, the common law, as modified and changed

by the constitution and statutes of the State wherein the court having

jurisdiction of such civil or criminal cause is held, so far as the same is

2 ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

I

In 1969, Shaw was tried in a Louisiana state court on

charges of having participated in a conspiracy to assassinate

President John F. Kennedy. He was acquitted by a jury but

within days was arrested on charges of having committed

perjury in his testimony at the conspiracy trial. Alleging that

these prosecutions were undertaken in bad faith, Shaw’s § 1983

complaint named as defendants the then District Attorney of

Orleans Parish, Jim Garrison, and five other persons, including

petitioner Willard E. Robertson, who was alleged to have lent

financial support to Garrison’s investigation of Shaw through

an organization known as “ Truth and Consequences.” On

Shaw’s application, the District Court enjoined prosecution of

the perjury action, 328 F. Supp. 390 (ED La. 1971), and the

Court of Appeals affirmed, 467 F. 2d 113 (CA5 1972).2

Since Shaw had sought damages as well as an injunction, the

parties continued with discovery after the injunction issued.

Trial was set for November 1974, but in August 1974 Shaw

died. The executor of his estate, respondent Edward F.

Wegmann, moved to be substituted as plaintiff, and the

District Court granted the motion.3 Petitioner and other

not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws of the United States, shall

be extended to and govern the said courts in the trial and disposition

of the cause, and, if it is of a criminal nature, in the infliction of pun

ishment on the party found guilty.”

2 The Court of Appeals held that this Court’s decision in Younger v.

Harris, 401 U. S. 37 (1971), did not bar the enjoining of the state per

jury prosecution, since the District Court’s “ finding of a bad faith prosecu

tion establishes irreparable injury both great and immediate for purposes

of the comity restraints discussed in Younger.” 467 F. 2d, at 122.

3 See Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 2 5 (a )(1 ). As the Court of Appeals ob

served, this rule “ does not resolve the question [of] what law of survival

of actions should be applied in this case. [It] simply describes the

manner in which parties are to be substituted in federal court once it is

determined that the applicable substantive law allows the action to survive

a party’s death.” 545 F. 2d 980, 982 (CA5 1977) (emphasis in original).

ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN 3

defendants then moved to dismiss the action on the ground

that it had abated on Shaw’s death.

The District Court denied the motion to dismiss. It began

its analysis by referring to 42 U. S. C. § 1988; this statute

provides that, when federal law is “ deficient” with regard to

“ suitable remedies” in federal civil rights actions, federal

courts are to be governed by

“ the common law, as modified and changed by the consti

tution and statutes of the State wherein the court having

jurisdiction of [the] civil . . . cause is held, so far as the

same is not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws

of the United States.”

The court found the federal civil rights laws to be “deficient

in not providing for survival.” 391 F. Supp. 1353, 1361 (ED

La. 1975). It then held that, under Louisiana law, an action

like Shaw’s would survive only in favor of a spouse, children,

parents, or siblings. Since no person with the requisite rela

tionship to Shaw was alive at the time of his death, his action

would have abated had state law been adopted as the federal

rule. But the court refused to apply state law, finding it

inconsistent with federal law, and in its place created “ a federal

common law of survival in civil rights actions in favor of the

personal representative of the deceased.” Id., at 1368.

On an interlocutory appeal taken pursuant to 28 U. S. C.

§ 1292 (b), the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit affirmed. The court first noted that all parties

agreed that, “if Louisiana law applies, Shaw’s § 1983 claim

abates.” 545 F. 2d 980, 982 (1977). Like the District Court,

the Court of Appeals applied 42 U. S. C. § 1988, found federal

law “deficient” with regard to survivorship, and held Louisiana

law “ inconsistent with the broad remedial purposes embodied

in the Civil Rights Acts.” 545 F. 2d, at 983. It offered a

number of justifications for creating a federal common-law

rule allowing respondent to continue Shaw’s action: such a

rule would better further the policies underlying § 1983, 545

4 ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

F. 2d, at 984-985; would “ foster[] the uniform application of

the civil rights laws,” id., at 985; and would be consistent with

“ [t]he marked tendency of the federal courts to allow actions

to survive in other areas of particular federal concern,” id., at

985. The court concluded that, “as a matter of federal com

mon law, a § 1983 action instituted by a plaintiff prior to his

death survives in favor of his estate.” 545 F. 2d, at 987.

We granted certiorari, ----- U. S. ----- (1977), and we now

reverse.

II

As both courts below held, and as both parties here have

assumed, the decision as to the applicable survivorship rule is

governed by 42 U. S. C. § 1988. This statute recognizes that

in certain areas “ federal law is unsuited or insufficient 'to

furnish suitable remedies’ ” ; federal law simply does not “cover

every issue that may arise in the context of a federal civil

rights action.” Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U. S. 693,

702, 703 (1973), quoting 42 U. S. C. § 1988. When federal

law is thus “deficient,” § 1988 instructs us to turn to “ the

common law, as modified and changed by the constitution and

statutes of the [forum] State,” as long as these are “ not

inconsistent with the Constitution and the laws of the United

States.” See n. 1, supra. Regardless of the source of the law

applied in a particular case, however, it is clear that the

ultimate rule adopted under § 1988 “ ‘is a federal rule respon

sive to the need whenever a federal right is impaired.’ ”

Moor v. Comity of Alameda, supra, at 703, quoting Sullivan v.

Little Hunting Park, 396 U. S, 229, 240 (I960).

As we noted in Moor v. County of Alameda, and as was

recognized by both courts below, one specific area not covered

by federal law is that relating to “ the survival of civil rights

actions under § 1983 upon the death of either the plaintiff or

defendant.” 411 U. S., at 702 n. 14.4 State statutes govem-

4 The dissenting opinion argues that, despite this lack of coverage, “ the

laws of the United States” are not necessarily “ [un]suitable” or “deficient

ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN 5

ing the survival of state actions do exist, however. These

statutes, which vary widely with regard to both the types of

claims that survive and the parties as to whom survivorship is

allowed, see W. Prosser, Handbook of the Law of Torts 900

901 (4th ed. 1971), were intended to modify the simple, if

harsh, 19th century common-law rule: “ [A ]n injured party’s

personal claim was [always] extinguished . . . upon the death

of either the injured party himself or the alleged wrongdoer.”

Moor v. County of Alameda, supra, at 702 n, 14; see Michigan

Central Railroad Co. v. Vreel'and, 227 U. S. 59, 67 (1913).

Under § 1988, this state statutory law, modifying the common

law,5 provides the principal reference point in determining

survival of civil rights actions, subject to the important proviso

that state law may not be applied when it is “ inconsistent

in the provisions necessary.” 42 U. S. C. § 1988; see post, at 2. Both

courts below found such a deficiency, however, and respondent here agrees

with them. 545 F. 2d, at 983; 391 F. Supp., at 1358-1361; Brief for

the Respondent 6.

There is a survivorship provision in 42 U. S. C. § 1986, but this statute

applies only with regard to “ the wrongs . . . mentioned in [42 U. S. C.]

section 1985.” Although Shaw’s complaint alleged causes of action under

§§ 1985 and 1986, the District Court dismissed this part of the complaint

for failure to state a 'claim upon which relief could be granted. 391 F.

Supp. 1353, 1356, 1369-1371 (ED La. 1975). These dismissals were not

challenged on the interlocutory appeal and are not at issue here.

5 Section 1988’s reference to “ the common law” might be interpreted as

a reference to the decisional law of the forum state, or as a reference to

the kind of general common law that was an established part of our

federal jurisprudence by the time of § 1988’s passage in 1866, see Swift v.

Tyson, 16 Pet. 1 (1842); cf. Moor v. County of Alameda, supra, 411 U. S.,

at 702 n. 14 (referring to the survivorship rule “at common law” ). The

latter interpretation has received some judicial and scholarly support. See,

e. g., Basista v. Weir, 340 F. 2d 74, 85-86, n. 10 (CA3 1965); Theis, Shaw

v. Garrison: Some Observations on 42 U. S. C. § 1988 and Federal Com

mon Law, 36 La. L. Rev. 681, 684-685 (1976). See also Carey v. Piphus,

No. 76-1149, slip op., at 10 n. 13 (Mar. 21, 1978). It makes no difference

for our purposes which interpretation is the correct one, because Louisiana

has a survivorship statute that, under the terms of § 1988, plainly governs

this case.

6 ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

with the Constitution and laws of the United States.” 42

U. S. C. § 1988. Because of this proviso, the courts below

refused to adopt as federal law the Louisiana survivorship

statute and in its place created a federal common-law rule.

Ill

In resolving questions of inconsistency between state and

federal law raised under § 1988, courts must look not only at

particular federal statutes and constitutional provisions, but

also at “ the policies expressed in [them].” Sullivan v. Little

Hunting Park, supra, 396 U. S., at 240; see Moor v. County of

Alameda, supra, 411 U. S., at 703. Of particular importance

is whether application of state lawT “ would be inconsistent with

the federal policy underlying the cause of action under consid

eration.” Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U. S.

454, 465 (1975). The instant cause of action arises under 42

U. S. C. § 1983, one of the “Reconstruction civil rights stat

utes” that this Court has accorded “ ‘a sweep as broad as

[their] language.’ ” Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U. S. 88, 97

(1971), quoting United States v. Price, 383 U. S. 787, 801

(1966).

Despite the broad sweep of § 1983, we can find nothing in

the statute or its underlying policies to indicate that a state

law causing abatement of a particular action should invariably

be ignored in favor of a rule of absolute survivorship. The

policies underlying § 1983 include compensation of persons

injured by deprivation of federal rights and prevention of

abuses of power by those acting under color of state law. See,

e. g., Carey v. Piphus, No. 76-1149, slip op., at 7 (Mar. 21,

1978); Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U. S. 225, 238-242 (1972);

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167, 172-187 (1961). No claim is

made here that Louisiana’s survivorship laws are in general

inconsistent with these policies, and indeed most Louisiana

actions survive the plaintiff’s death. See La. Code Civ. Proc.

Art. 428; La. Civ. Code Art. 2315. Moreover, certain types of

actions that would abate automatically on the plaintiff’s death

ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN 7

in many States— for example, actions for defamation and mali

cious prosecution— would apparently survive in Louisiana.6 7 8

In actions other than those for damage to property, however,

Louisiana does not allow the deceased’s personal representative

to be substituted as plaintiff; rather, the action survives only

in favor of a spouse, children, parents, or siblings. See 391 P.

Supp., at 1361-1363; La. Civ. Code Art. 2315 ; / . Wilton Jones

Co. v. Liberty Mutual Ins. Co., 248 So. 2d 878 (La. Ct. App.)

(en banc).7 But surely few persons are not survived by one

of these close relatives, and in any event no contention is made

here that Louisiana’s decision to restrict certain survivorship

rights in this manner is an unreasonable one.8

6 An action for defamation abates on the plaintiff’s death in the vast

majority of States, see W. Prosser, Handbook of the Law of Torts 900-901

(4th ed. 1971), and a large number of States also provide for abatement

of malicious prosecution actions, see, e. g., Dean v. Shirer, 547 F. 2d 227,

229-230 (CA4 1976) (South Carolina law ); Hall v. Wooten, 506 F. 2d 564,

569 (CA6 1974) (Kentucky law). See also 391 F. Supp., at 1364 n. 17.

In Louisiana, an action for defamation or malicious prosecution would

apparently survive (assuming that one of the relatives specified in La.

Civ. Code Art. 2315 survives the deceased, as discussed in text injra) ; such

an action seems not to fall into the category of “strictly personal” actions,

La. Code Civ. Proc. Art. 428, that automatically abate on the plaintiff’s

death. See Johnson, Death on the Callais Coach: The Mystery of Louisi

ana Wrongful Death and Survival Actions, 37 La.. L. Rev. 1, 6 n. 23, 52

and n. 252 (1976). See also Official Revision Comment (c) to La. Code

Civ. Proc. Art. 428.

7 For those actions that do not abate automatically on the plaintiff’s

death, most States apparently allow the personal representative of the

deceased to be substituted as plaintiff. See 391 F. Supp., at 1364, and

n. 18.

8 The reasonableness of Louisiana’s approach is suggested by the fact

that several federal statutes providing for survival take the same approach,

limiting survival to specific named relatives. See, e. g., 33 U. S. C.

§ 908 (d) (Longshoremen’s and Harbor Workers’ Compensation A ct); 45

U. S. C. § 59 (Federal Employers’ Liability Act). The approach taken by

federal statutes in other substantive areas cannot, of course, bind a federal

court in a § 1983 action, nor does the fact that a state survivorship statute

may be reasonable by itself resolve the question whether it is “ inconsistent

8 ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

It is therefore difficult to see how any of § 1983’s policies

would be undermined if Shaw’s action were to abate. The

goal of compensating those injured by a deprivation of rights

provides no basis for requiring compensation of one who is

merely suing as the executor of the deceased’s estate.9 And,

given that most Louisiana actions survive the plaintiff’s

death, the fact that a particular action might abate surely

would not adversely affect § 1983’s role in preventing official

illegality, at least in situations in which there is no claim

that the illegality caused the plaintiff’s death. A state offi

cial contemplating illegal activity must always be prepared

to face the prospect of a § 1983 action being filed against him.

In light of this prospect, even an official aware of the intrica

cies of Louisiana survivorship law would hardly be influenced

in his behavior by its provisions.10

It is true that § 1983 provides “ a uniquely federal remedy

against incursions under the claimed authority of state law

upon rights secured by the Constitution and laws of the

Nation.” Mitchum v. Foster, supra, 407 U. S., at 239. That

a federal remedy should be available, however, does not mean

that a § 1983 plaintiff (or his representative) must be allowed

to continue an action in disregard of the state law to which

§ 1988 refers us. A state statute cannot be considered “ incon

sistent” with federal law merely because the statute causes

the plaintiff to lose the litigation. If success of the § 1983

with the Constitution and laws of the United States.” 42 U. S. C.

§ 1988.

9 This does not, of course, preclude survival of a § 1983 action when

such is allowed by state law, see Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U. S.

693, 702-703, n. 14 (1973), nor does it preclude recovery by survivors who

are suing under § 1983 for injury to their own interests.

10 In order to find even a marginal influence on behavior as a result of

Louisiana’s survivorship provisions, one would have to make the rather

far-fetched assumptions that a state official had both the desire and the

ability deliberately to select as victims only those persons who would die

before conclusion of the § 1983 suit (for reasons entirely unconnected with

the official illegality) and who would not be survived by any close relatives.

ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN 9

action were the only benchmark, there would be no reason at

all to look to state law, for the appropriate rule would then

always be the one favoring the plaintiff, and its source would

be essentially irrelevant. But § 1988 quite clearly instructs

us to refer to state statutes; it does not say that state law is

to be accepted or rejected based solely on which side is advan

taged thereby. Under the circumstances presented here, the

fact that Shaw was not survived by one of several close

relatives should not itself be sufficient to cause the Louisiana

survivorship provisions to be deemed “ inconsistent with the

Constitution and laws of the United States.” 42 U. S. C.

§ 1988.11

IV

Our holding today is a narrow one, limited to situations in

which no claim is made that state law generally is inhospitable

to survival of § 1983 actions and in which the particular

application of state survivorship law, while it may cause

abatement of the action, has no independent adverse effect on

the policies underlying § 1983. A different situation might 11

11 In addition to referring to the policies underlying § 1983, the Court

of Appeals based its decision in part on the desirability of uniformity in

the application of the civil rights laws and on the fact that the federal

courts have allowed survival “ in other areas of particular federal con

cern . . . where statutory guidance on the matter is lacking.” 545 F. 2d,

at 985; see p. 4, supra. With regard to the latter point, however, we do

not find “statutory guidance . . . lacking” ; § 1988 instructs us to turn to

state laws, unless an “inconsistency” with federal law is found. While

the courts below found such an inconsistency, we do not agree, as discussed

in text supra, and hence the survivorship rules in areas where the courts

are free to develop federal common law—without first referring to state

law and finding an inconsistency—can have no bearing on our decision

here. Similarly, whatever the value of nationwide uniformity in areas

of civil rights enforcement where Congress has not spoken, in the areas

to which § 1988 is applicable Congress has provided direction, indicating

that state law will often provide the content of the federal remedial rule.

This statutory reliance on state law obviously means that there will not be

nationwide uniformity on these issues.

10 ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

well be presented, as the District Court noted, if state law

“ did not provide for survival of any tort actions,” 391 F.

Supp., at 1363, or if it significantly restricted the types of

actions that survive. Cf. Carey v. Piphus, supra, slip op., at

11 (failure of common law to “recognize an analogous cause

of action” is not sufficient reason to deny compensation to

§ 1983 plaintiff). We intimate no view, moreover, about

whether abatement based on state law could be allowed in a

situation in which deprivation of federal rights caused death.

See p. 8, and n. 10, supra; cf. Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F. 2d 401

(CA5 1961) (deceased allegedly beaten to death by policemen;

state survival law applied in favor of his widow and estate).

Here it is agreed that Shaw’s death was not caused by

the deprivation of rights for which he sued under § 1983, and

Louisiana law provides for the survival of most tort actions.

Respondent’s only complaint about Louisiana law is that it

would cause Shaw’s action to abate. We conclude that the

mere fact of abatement of a particular lawsuit is not sufficient

ground to declare state law “ inconsistent” with federal law.

Accordingly, the judgment of the Court of Appeals is

Reversed.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 77-178

Willard E, Robertson, Petitioner,

v.

Edward F. Wegmann, Executor of

the Estate of Clay L. Shaw,

et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit.

[May 31, 1978]

M r . Ju stic e B l a c k m u n , with whom M r . Ju s t ic e B r e n n a n

and M r . Ju s t ic e W h it e join, dissenting.

It is disturbing to see the Court, in this decision, although

almost apologetically self-described as “a narrow one,” ante,

p. 9, cut back on what is acknowledged, id., p. 6, to be the

“broad sweep” of 42 U. S. C. § 1983. Accordingly, I dissent.

I do not read the emphasis of § 1988, as the Court does,

ante, p. 1 and p. 9 n. 11, to the effect that the Federal District

Court “ was required to adopt” the Louisiana statute, and was

free to look to federal common law only as a secondary matter.

It seems to me that this places the cart before the horse.

Section 1988 requires the utilization of federal law ( “shall be

exercised and enforced in conformity with the laws of the

United States” ) . It authorizes resort to the state statute only

if the federal laws “are not adapted to the object” of “protec

tion of all persons in the United States in their civil rights,

and for their vindication” or are “deficient in the provisions

necessary to furnish suitable remedies and punish offenses

against law.” Even then, state statutes are an alternative

source of law only if “not inconsistent with the Constitution

and laws of the United States.” Surely, federal law is the rule

and not the exception.

Accepting this as the proper starting point, it necessarily

follows, it seems to me, that the judgment of the Court of

2 ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

Appeals must be affirmed, not reversed. To be sure, survivor

ship of a civil rights action under § 1983 upon the death of

either party is not specifically covered by the federal statute.

But that does not mean that “ the laws of the United States”

are not “ suitable” or are “ not adapted to the object” or are

“deficient in the provisions necessary.” The federal law and

the underlying federal policy stand bright and clear. And in

the light of that brightness and of that clarity, I see no need

to resort to the myriad of state rules governing the survival

of state actions.

First. In Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U. S.

229 (1969), a case that concerned the availability of com

pensatory damages for a violation of § 1982, a remedial ques

tion, as here, not governed explicitly by any federal statute

other than § 1988, Mr. Justice Douglas, writing for the Court,

painted with a broad brush the scope of the federal court’s

choice-of-law authority:

“ [A ]s we read § 1988, . . . both federal and state rules on

damages may be utilized, whichever better serves the

policies expressed in the federal statutes. . . . The rule

of damages, whether drawn from federal or state sources,

is a federal rule responsive to the need whenever a federal

right is impaired” (emphasis added). 396 U. S., at 240.

The Court’s present reading of § 1988 seems to me to be

hyperlogical and sadly out of line with the precept set forth in

that quoted material. The statute was intended to give courts

flexibility to shape their procedures and remedies in accord

with the underlying policies of the Civil Rights Acts, choosing

whichever rule “ better serves” those policies (emphasis added).

I do not understand the Court to deny a federal court’s

authority under § 1988 to reject state law when, to apply it,

seriously undermines substantial federal concerns. But I do

not accept the Court’s apparent conclusion that, absent such

an extreme inconsistency, § 1988 restricts courts to state law

on matters of procedure and remedy. That conclusion too

ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN 3

often would interfere with the efficient redress of constitutional

rights.

Second. The Court’s reading of § 1988 cannot easily be

squared with its treatment of the problems of immunity and

damages under the Civil Rights Acts. Only this Term, in

Carey v. Piphus,-----IT. S .------(1978), the Court set a rule for

the award of damages under § 1983 for deprivation of proce

dural due process by resort to “ federal common law.” Though

the case arose from Illinois, the Court did not feel compelled

to inquire into Illinois’ statutory or decisional law of damages,

nor to test that law for possible “inconsistency” with the

federal scheme, before embracing a federal common-law rule.

Instead, the Court fashioned a federal damages rule, from

common law sources and its view of the type of injury, to

govern such cases uniformly state-to-state. Carey v. Piphus,

slip op., at pp. 10-12, and n. 13.

Similarly, in constructing immunities under § 1983, the

Court has consistently relied on federal common-law rules.

As Carey v. Piphus recognizes, slip op., at p. 10 n. 13, in

attributing immunity to prosecutors, Imbler v. Pachtman, 424

U. S. 409, 417-419 (1976); to judges Pierson v. Ray, 386 IT. S.

547, 554-555 (1967); and to other officials, matters on which

the language of § 1983 is silent, we have not felt bound by the

tort immunities recognized in the particular forum State and,

only after finding an “ inconsistency” with federal standards,

then considered a uniform federal rule. Instead, the immu

nities have been fashioned in light of historic common-law

concerns and the policies of the Civil Rights Acts.1

1 Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U. S. 693 (1973), is not to the con

trary. There, the Court held that § 1988 does not permit the importation

from state law of a new cause of action. In passing dictum, 411 U. S.,

at 702 n. 14, the Court noted the approach taken to the survival problem

by several lower federal courts. In those cases, because the applicable

state statute permitted survival, the lower courts had little occasion to

consider the need for a uniform federal rule.

4 ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

Third. A flexible reading of § 1988, permitting resort to a

federal rule of survival beeause it "better serves” the policies

of the Civil Rights Acts, would be consistent with the metho

dology employed in the other major choice-of-law provision in

the federal structure, namely, the Rules of Decision Act. 28

U. S. C. § 1652.2 That Act provides that state law is to govern

a civil trial in a federal court “except where the Constitution

or treaties of the United States or Acts of Congress otherwise

require or provide.” The exception has not been interpreted

in a crabbed or wooden fashion, but, instead, has been used to

give expression to important federal interests. Thus, for ex

ample, the exception has been used to apply a federal common

law of labor contracts in suits under § 301 (a) of the Labor

Management Relations Act of 1947, 29 U. S. C. § 185 (a),

Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills, 353 U. S. 448 (1957) ;

to apply federal common law to transactions in commercial

paper issued by the United States where the United States is

a party, Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U. S. 363

(1943); and to avoid application of governing state law to the

reservation of mineral rights in a land acquisition agreement

to which the United States was a party and that bore heavily

upon a federal wildlife regulatory program, United States v.

Little Lake Misere Land Co., 412 U. S. 580 (1973). See also

Auto Workers v. Ho osier Cardinal Corp., 383 U. S. 696, 709

(1966): “ [Sjtate law is applied [under the Rules of Decision

Act] only because it supplements and fulfills federal policy,

and the ultimate question is what federal policy requires.”

( W h i t e , J., dissenting.)

Just as the Rules of Decision Act cases disregard state law

where there is conflict with federal policy, even though no

explicit conflict with the terms of a federal statute, so, too,

2 “The laws of the several states, except where the Constitution or

treaties of the United States or Acts of Congress otherwise require or

provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in civil actions in the courts

of the United States, in cases where they apply.”

ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN 5

state remedial and procedural law must be disregarded under

§ 1988 where that law fails to give adequate expression to

important federal concerns. See Sullivan v. Little Hunting

Park, Inc., supra. The opponents of the 1866 Act were dis

tinctly aware that the legislation that became § 1988 would

give the federal courts power to shape federal common-law

rules. See, for example; the protesting remarks of Congress

man Kerr relative to § 3 of the 1866 Act (which contained

the predecessor version of § 1988):

“I might go on and in this manner illustrate the practical

working of this extraordinary measure. . . . i[T]he

authors of this bill feared, very properly too, that the

system of laws heretofore administered in the Federal

courts might fail to supply any precedent to guide the

courts in the enforcement of the strange provisions of

this bill, and not to be thwarted by this difficulty, they

confer upon the courts the power of judicial legislation,

the power to make such other laws as they may think

necessary. Such is the practical effect of the last clause

of the third section [of § 1988] . . . . That is to say,

the Federal courts may, in such cases, make such rules

and apply such law as they please, and call it common

law” (emphasis in original). Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

1st Seas., 1271 (1866).

Fourth. Section 1983’s critical concerns are compensation

of the victims of unconstitutional action, and deterrence of

like misconduct in the future. Any crabbed rule of survivor

ship obviously interferes directly with the second critical in

terest and may well interfere with the first.

The unsuitability of Louisiana’s law is shown by the very

case at hand. It will happen not infrequently that a dece

dent’s only survivor or survivors are nonrelatives or collateral

relatives who do not fit within the four named classes of

Louisiana statutory survivors. Though the Court surmises,

ante, p. 7, that “surely few persons are not survived” by a

6 ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

spouse, children, parents, or siblings, any lawyer who has

had experience in estate planning or in probating estates

knows that that situation is frequently encountered. The

Louisiana survivorship rule applies no matter how malicious

or ill-intentioned a defendant’s action was. In this case, as

the Court acknowledges, id., at 2 n. 2, the District Court

found that defendant Garrison brought state perjury charges

against plaintiff Shaw “ in bad faith and for purposes of

harassment,” 328 F. Supp. 390, 400, a finding that the Court

of Appeals affirmed as not clearly erroneous. 467 F. 2d 113,

122. The federal interest in specific deterrence, when there

was malicious intention to deprive a person of his constitu

tional rights, is particularly strong, as Cary v. Piphus inti

mates, slip op., at pp. 9^10, n. 11. Insuring'a specific de

terrent under federal law gains importance from the very

premise of the Civil Rights Act that state tort policy often

is inadequate to deter violations of the constitutional rights

of disfavored groups.

The Louisiana rule requiring abatement appears to apply

even where the death was intentional and caused, say, by a

beating delivered by a defendant. The Court does not deny

this result, merely declaiming, ante, p. 10, that in such a case

it might reconsider the applicability of the Louisiana survivor

ship statute. But the Court does not explain how either

certainty or federalism is served by such a variegated appli

cation of the Louisiana statute, nor how an abatement rule

would be workable when made to depend on a fact of causation

often requiring an entire trial to prove.

It makes no sense to me to make even a passing reference,

id., at 8, to behavioral influence. The Court opines that no

official aware of the intricacies of Louisiana survivorship law

would “ be influenced in his behavior by its provisions.” But

the defendants in Shaw’s litigation obviously have been

“sweating it out” through the several years of proceedings

ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN 7

and litigation in this case. One can imagine the relief oc

casioned when the realization dawned that Shaw’s death

might— just might— abate the action. To that extent, the

deterrent against behavior such as that attributed to the de

fendants in this case surely has been lessened.

As to compensation, it is no answer to intimate, as the Court

does, ibid., that Shaw’s particular survivors were not person

ally injured, for obviously had Shaw been survived by parents

or siblings, the cause of action would exist despite the absence

in them of so deep and personal an affront, or any at all, as

Shaw himself was alleged to have sustained. The Court pro

pounds the unreasoned conclusion, ibid., that the “ goal of

compensating those injured by a deprivation of rights pro

vides no basis for requiring compensation of one who is merely

suing as the executor of the deceased’s estate.” But the

Court does not purport to explain why it is consistent with

the purposes of § 1983 to recognize a derivative or independ

ent interest in a brother or parent, while denying similar inter

est to a nephew, grandparent, or legatee.

Fifth. The Court regards the Louisiana system’s structur

ing of survivorship rights as not unreasonable. Ante, p. 7.

The observation, of course, is a gratuitous one, for as the

Court immediately observes, id., n. 8, it does not resolve

the issue that confronts us here. We are not concerned with

the reasonableness of the Louisiana survivorship statute in

allocating tort recoveries. We are concerned with its applica

tion in the face of a claim of civil rights guaranteed the

decedent by federal law. Similarly, the Court’s observation

that the Longshoremen’s and Harbor Workers’ Compensation

Act, 33 U. S. C. § 908 (d), 909 (d) (1970 ed., Supp. V ), and

Federal Employers’ Liability Act, 45 U. S. C. § 59, limit

survival to specific named relatives or dependents (albeit a

larger class of survivors than the Louisiana statute allows) is

gratuitous. Those statutes have as their main purpose loss-

8 ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN

shifting and compensation, rather than deterrence of unconsti

tutional conduct. And, although the Court does not mention

it, any reference to the survival rule provided in 42 U. S. C.

§ 1986 governing that statute’s principle of vicarious liability,

would be off-point. There it was the extraordinary character

of the liability created by § 1986, of failing to prevent wrongful

acts, that apparently induced Congress to limit recovery to

widows or next-of-kin in a specified amount of statutory

damages. Cf. Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess., 749-752,

756-763 (1871); Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U. S., at 710

n. 26.

The Court acknowledges, ante, p. 6, “ the broad sweep of

§ 1983,” but seeks to justify the application of a rule of nonsur

vivorship here because it feels that Louisiana is comparatively

generous as to survivorship anyway. This grudging allowance

of what the Louisiana statute does not give, just because it

gives in part, seems to me to grind adversely against the

statute’s “broad sweep.” Would the Court’s decision be other

wise if actions for defamation and malicious prosecution in

fact did not survive at all in Louisiana? The Court by

omission admits, ante, p. 7, and n. 6, that that question of

survival has not been litigated in Louisiana. See Johnson,

Death on the Callais Coach: The Mystery of Louisiana

Wrongful Death and Survival Actions, 37 La. L. Rev. 1, 6 n. 23

(1976). Defamation and malicious prosecution actions wholly

abate upon the death of the plaintiff in a large number of

States, see ante, p. 7, and n. 6. Does it make sense to apply a

federal rule of survivorship in those States while preserving a

different state rule, stingier than the federal rule, in Louisiana?

Sixth. A federal rule of survivorship allows uniformity and

counsel immediately know the answer. Litigants identically

aggrieved in their federal civil rights, residing in geographically

adjacent States, will not have differing results due to the

vagaries of state law. Litigants need not engage in uncertain

characterization of a § 1983 action in terms of its nearest tort

cousin, a questionable procedure to begin with, since the

ROBERTSON v. WEGMANN 9

interests protected by tort law and constitutional law may be

quite different. Nor will federal rights depend on the arcane

intricacies of state survival law— which differs in Louisiana

according to whether the right is “strictly personal,” La. Civ.

Proc. Art. 428; whether the action concerns property damage,

La. Civ. Code Art. 2315, para. 2; or concerns “ other damages,”

id., para. 3. See 37 La. L. Rev., at 52.

The policies favoring so-called “ absolute” survivorship, viz,

survivorship in favor of a decedent’s nonrelated legatees in

the absence o f familial legatees, are the simple goals of

uniformity, deterrence, and perhaps compensation. A defend

ant who has violated someone’s constitutional rights has no

legitimate interest in a windfall release upon the death of the

victim. A plaintiff’s interest in certainty, in an equal remedy,

and in deterrence support such an absolute rule. I regard as

unanswered the justifications advanced by the District Court

and the Court of Appeals: uniformity of decisions and fulfill

ment of the great purposes of § 1983. 391 Supp., at 1359,

1363-1365; 545 F. 2d, at 983.

Seventh. Rejecting Louisiana’s survivorship limitations does

not mean that state procedure and state remedies will cease to

serve as important sources of civil rights law. State law, for

instance, may well be a suitable source of statutes of limita

tion, since that is a rule for which litigants prudently can plan.

Rejecting Louisiana’s survivorship limitations means only that

state rules are subject to some scrutiny for suitability. Here

the deterrent purpose of § 1983 is disserved by Louisiana’s rule

of abatement.

It is unfortunate that the Court restricts the reach of § 1983

by today’s decision construing § 1988. Congress now must act

again if the gap in remedy is to be filled.