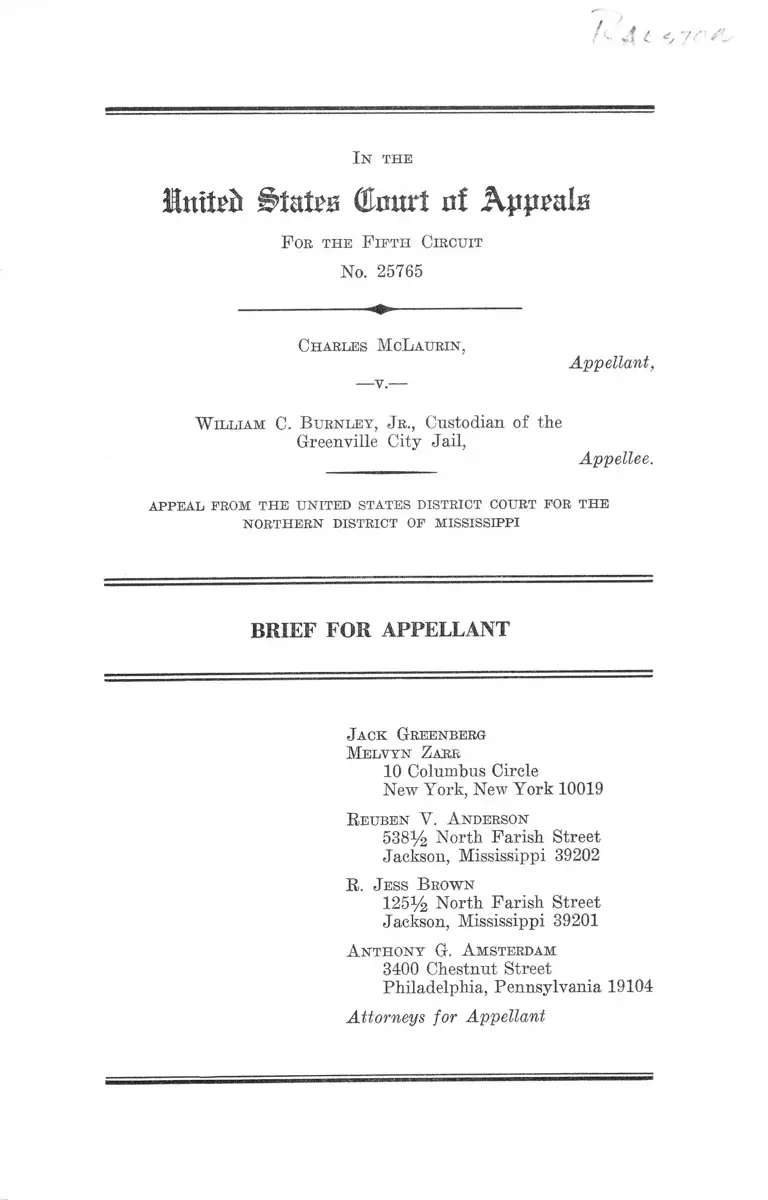

McLaurin v. Burnley Jr. Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McLaurin v. Burnley Jr. Brief for Appellant, 1968. 49887eba-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/383bba6c-ba35-4392-bb56-58aa60300fdc/mclaurin-v-burnley-jr-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

4 ( *, 7 As

I n t h e

States ©curt of Appeals

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 25765

Charles McLaurin,

— v.-

Appellant,

W illiam C. B urnley, Jr., Custodian of the

Greenville City Jail,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Jack Greenberg

Melvyn Z.VRf.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Reuben Y. A nderson

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

R. Jess B rown

125% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the C ase........................................................ 1

Specification of Error ...................................................... 12

A rgument

Appellant’s Speech Is Protected From Punishment

Under Mississippi’s Vague and Overbroad Breach

of the Peace Statute, Miss. Code Ann. §2089.5

(1966 Supp.), by the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States .... 13

Conclusion ............................................. 23

Table op Cases

Ashton v. Kentucky, 384 U. S. 195 (1966) ................... 18

Bolton v. City of Greenville, 253 Miss. 656, 178 So. 2d

667 (1965) .......................................................................... 3

Bynum v. City of Greenville, 253 Miss. 667, 178 So, 2d

672 (1965) ........................................................................ 3

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (1940) .......13,14,18

Carmichael v. Allen, 267 F. Supp. 985 (N. D, Ga. 1967) 20

Chaplin sky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 (1942) .. 15

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965) ..14,15,17,18, 21, 22

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 IT. S. 479 (1965) .............. 18

ii

PAGE

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) ....15,16,

17,18

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951) ................... 15

NAACP v. Button, 371 IT. S. 415 (1963) ....................... 18

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 IT. S. 254 (1964) 22

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 IT. S. 87 (1965) .... 18

Stromberg v. California, 283 IT. S. 359 (1931) ........... 18

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 IT. S. 1 (1949) ................... 20

Thomas v. Collins, 323 IT. S. 516 (1945) ....................... 18

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 IT. S. 287 (1942) ....... 18

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) ....................... 18

Statutes Involved

Miss. Code Ann. §2089.5 (1966 Supp.) ........ .......... 12,13,20

Section 252, Code of Ordinances, City of Greenville,

Mississippi ........................................................................ 12

In the

Imleii GImirt of Kpprais

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 25765

Charles McL aurin,

Appellant,

W illiam C. B urnley, Jr., Custodian of the

Greenville City Jail,

Appellee.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi

denying appellant’s petition for writ of habeas corpus.1

Appellant’s petition was filed February 14, 1967 and al

1 The order appealed from was dated December 29, 1967 and

entered January 2, 1968 (R. 254-55). The district court issued a

certificate of probable cause on January 15, 1968 (R. 263-64) and

a timely notice of appeal was filed January 16, 1968 (R. 265). The

district court’s opinion is reported at 279 F. Supp. 220.

2

leged, in essence, that his confinement2 by appellee pun

ished him for the exercise of his federal constitutional

rights of free speech, assembly and petition (R. 3-7).

The case was submitted to the district court on the record

made in the state court (R. 237-38, 240-41; 279 F. Supp.

220, 222). That record, viewed as a whole, reveals the

following.

On July 1, 1963, appellant, a young Negro civil rights

worker (R. 112-16), attended the trial of two Negro girls

in the Police Court of the City of Greenville, Mississippi.

The girls stood charged with disorderly conduct because

they refused to leave a traditionally segregated public park

when the police, fearing that the crowd of white persons

that was gathering around them would become violent, or

dered them to do so. The trial was attended by approxi

mately 300 persons, approximately half of them Negroes

(R. 37). During the trial, appellant attempted to sit on

the side of the courtroom customarily reserved for whites,

but he was ordered out of that section (R. 37, 44-46, 48-50,

104-05). Appellant left the courtroom and protested the

segregated seating pattern to Police Chief William C. Burn

ley, Jr., appellee herein (R. 84-85, 105). His protest was

futile, and he was then denied readmission to the courtroom

(R. 105). Appellant then left the municipal building, which

housed the municipal court and the police station, and

stood outside on the sidewalk, waiting for the trial to end

(R. 106). About 50 Negroes were standing outside the

building, having been denied admission to the courtroom

2 Subsequent to the filing of his petition, appellant was released

on bond pending decision by the district court (R. 9-10). He re

mains enlarged on $1,500 bond pending this appeal by order of the

district court (R. 264-65).

3

because the Negro side was completely filled (although

there was some space on the white side) (E. 106).

The girls were convicted by the municipal court.3

As the spectators left the municipal building, appellant

began to address them.

What appellant said was the subject of testimony by

three Greenville police officers and appellant.

Arresting Officer Willie Carson testified:

McLaurin began to talk protesting the Court’s de

cision in words like, what are you going to do about

it; you going to take this; it ain’t right . . . (R. 39).

̂ ̂ ^

He said it was wrong— segregation was wrong—

what we going to do about it. Mostly, he was protest

ing the Judge’s decision (R. 42).

* * * # #

He was on the outside—I said, preaching because

my experience in the words he was using and waving

and shouting I said, I told him he couldn’t preach out

on the streets (R. 52).

̂ ̂ ^

. . . [H]e said this, what you people going to do

about this; this is wrong, the white Caucasian, this law

is wrong; you going to take it; you going to let them

3 In 1965, their convictions were reversed by the Mississippi

Supreme Court. Bolton v. City of Greenville, 253 Miss. 656, 178

So. 2d 667 (1965) and Bynum v. City of Greenville, 253 Miss. 667,

178 So. 2d 672 (1965).

4

get away with it. I heard those words there, and then

the people began to just come in.

Q. Now, was the defendant cursing? A. No, I

didn’t hear him curse.

Q. He didn’t use any profane language, if he did you

didn’t hear him? A. No (R. 53).

Greenville Police Captain Harvey Tackett testified:

He started waving his hands, shouting real loud to

the people that were walking on. And, they, most of

them, immediately turned and came back around him.

He then left the sidewalk and jumped up on the steps

of the Police Station and continued to shout and

holler, ask people, you see what’s happening, what you

going to do about it, and such phrases as that (R. 64).

-v. -y. .v.w w w w

Q. Now, did you hear the defendant use any kind of

vulgar language of any kind? A. I did not.

jfc JJ, -sfe Jfc MiV " A * 'A* "A' ^

Q. . . . Did he do anything that would appear to you

to have been vulgar by his actions? . . . A. No he

didn’t (R. 73).

Greenville Police Chief William C. Burnley, Jr. testified:

Q. What was he saying? A. What are you going

to do? Are you going to let this happen? Statements

of that type (R. 77).

Appellant testified:

. . . I moved out in front of the Municipal building.

As the people was coming out of the building—well,

5

they was coming out just looking as if, you k n o w -

some of the people seemed to be kinda shocked as to

the conviction of the people, as if they thought they

wasn’t going to be convicted, and so, people were

standing around out there. And so, at that time I felt

that they didn’t really know what had happened and

what was going on. Some people had had to stand on

the outside that could have gone into the Courtroom

and taken a seat had it not been for the system they

were using to seat people, others that "were there didn’t

really know why these kids had been convicted. So,

at this time I felt that the 1st Amendment of the

United States Constitution gives the right of freedom

of speech and peaceful assembly. The people wTere

peacefully assembled out there, and so, I made a few

statements. My job is voter registration, to get Ne

groes registered to vote. And so, then, I started try

ing to get the attention of the people to tell them

that by registering and voting this couldn’t have hap

pened. And, at this time, Officer Carson, as I started to

talk, came up and—well, he caught me by the shoulder,

took me by my arm, and he said, you can’t make a

public speech without a permit, you cannot make a

public speech in front of the building without a per

mit (It. 107).

# # * * *

. . . And, at that time—the time that I was out there

Officer Carson took me by the arm then, and I con

tinued to talk as he carried me in. I was saying dif

ferent things like, this wouldn’t have happened if

Negroes were registered to vote, that in Washington

County Negroes are in the majority of the popula

tion— 50 per cent of the population is Negro and that

6

they could have used the park or any other thing had

they been registered voters (R. 108).

■u> -v* .y. -v.w w w w w

I meant that if they were registered—if the people

would register to vote, were to get in line and exer

cise their duties and responsibilities as citizens, as

Negro citizens, and as citizens of the United States,

they could change some of these things. They could

change the policy of being arrested in a park that

they paid for as well as any other people and that

there wouldn’t be such parks that was designated for

Whites and for Negroes. This was my intentions

and that being arrested there, I felt that they was in

citing a riot then, if the people—if the policemen-—

there were policemen out there, and if at any time

they felt that the crowd was going to get unruly,

it was their job to move the crowd—there was no

attempt made to dispurse the crowd. Instead, I was

arrested for making—for saying what I was saying,

you know, I was arrested not—I don’t think there

was any question as to whether, thought whether the

crowd—what would they do, tear down the building,

you know. Surely, I didn’t think they were going to

attack me or attack the policemen there, because we

have advocated non-violence, not violence—non-vio

lence is our way of doing things. And, the only thing

that I had in mind was to get them to register to vote

and to realize what was happening, and I felt that I

had a right to do this under the 1st Amendment.

Q. I take it then, that you did not at any time make

any statements or of any kind to encourage them to

attack anybody, did you? Did you tell them to rush

inside and attack the Judge for his decision? A. No,

7

I did not. In fact I never really finished—I was

dragged away before I could get out what I wanted

to get out. Each time—as I was carried—as I was

being carried into the building, I was talking and I

never really made my point (R. 109-10).

The three police officers and appellant also testified as

to the reaction of the crowd to Appellant’s speech.

Officer Carson testified:

Q. And, what was the crowd doing! A. They were

talking. Everybody seemed interested in what he was

saying.

Q. What was the tempo of that crowd! A. Well,

at the time as I could judge, everybody was getting

disturbed.

Q. And, what do you mean by disturbed, Willie!

A. They didn’t like the decision— of what he was

talking—what he was telling them (II. 40).

# * # # #

Q. Just tell—just describe that situation as best

you can, Willie. What you saw and what was going on

in your presence after the defendant began talking

to those people! A. Well, my experience in my opin

ion was a very tense situation and had it kept on any

thing could happen.

Q. How do you know it was tense! A. We could

tell the crowd and mumbling in the crowd . . . (R. 41-

42).

* * # * *

Q. Did you hear anybody in the crowd hollering!

A. Oh, you could hear them talking back and hear

them saying, it ain’t right.

8

Q. How’s that? A. You could hear voices—it ain’t

right, you know.

Q. But, you didn’t hear any oral threats made by

anybody in the crowd, did you— on anybody’s life?

A. No, I didn’t.

Q. Or property, you didn’t hear that, did you? A.

No I didn’t (R. 60-61).

Captain Tackett testified:

They seemed to be crowding more and more around

the door of the Police Station and the mumbling and

all began to get louder. It seemed as though they

were going to try to take the situation in their own

hands (R. 66).

Q. I believe you said that you heard some sort of

muttering among the various people in the crowd, is

that correct? A. That’s right.

Q. And, I believe you told the Court you couldn’t

understand what they were saying? A. I could not.

Q. So you couldn’t tell the crowd was saying, let’s

get them? A. No I couldn’t.

Q. Or let’s go get that judge? A. I could not. I

could say what I heard the defendant McLaurin say.

Q. . . . [D] id you observe or make any observation

of anybody in the crowd was armed at the time? A.

I didn’t see anyone.

Q. Was the crowd hooping, hollering and yelling

when they were in that vicinity? Were the crowd

themselves doing a lot of hooping and yelling? A.

No they wasn’t (R. 71-72).

9

Police Chief Burnley testified:

Q. Did you hear what the crowd was saying? A.

No, it was a general mumbling, utterance. I couldn’t

distinguish anything they were particularly saying.

Q. So then, you couldn’t tell the Court, then, that

there were people in the crowd making any threaten

ing statements or anything like that? A. Well, the

general demeanor of the crowd, the appearance of the

crowd at a tense situation like that would automat

ically inform me that it was a tense and sticky situa

tion.

Q. But you didn’t hear any verbal threats? A. No

I did not (R. 81).

Appellant testified:

Q. Did the crowd appear to be angry and in a tense,

angry mood? A. I feel that the crowd was sorta up

set as to the out come of the trial, but certainly the

words that I was using wouldn’t have caused them to

jump—to go in there and try to beat up the Judge.

Negroes know they can’t go beat up the Judge and

be justified, and tear down the building and be justi

fied, or jump on a policeman in the State of Mississippi

and be justified.

Q. Well, it wouldn’t be justified in any— A. Any

place—but they know better—there are certain things

that they know (R. 110-11).

# # * # *

Q. Now, as they came out, you tell this jury that

the Negroes that you observed seemed shocked, is that

correct? A. Right.

Q. And, they seemed upset? A. Right.

10

Q. And, that they were shocked and upset at what

had taken place in the building, is that correct? A.

Yes.

Q. And, that’s what you were talking to them about,

is it not ? A . That’s right.

Q. And, that’s what you ask them, what are you

going to do about it, is that correct? A. Not in the

way you say it, no.

Q. Well, that’s what you told them, isn’t it? A. I

wanted to know what would they do to get to try to

change—what would they do to register to vote. I

would have brought these things out had I been given

the opportunity (R. 120).

# # * # *

I was the one that was standing up there doing

the talking and I at no time felt that these people

were going to attack me. These were people that I had

talked with before, people that I know as well as my

own people. I didn’t feel that they were going to come

up and beat me up, you know, do me any harm, and

I didn’t feel the words that I was saying, I never

directed them to go in and get anybody else. I felt

that if it was a tense situation out there that these

people would—first of all they knew, some of them,

that the kids had tried to use the park. They needed

some kind of idea as to what steps to take. They

were up-set; they were restless. The expressions on

their faces characterized by restless energy, that they

felt that something should be done. But, then all it

needed was a leader, and I was going to try to show

them where they could register their protest with the

11

Mayor, and I didn’t feel that they were going to come

up and attack me (R. 202).

# # # * #

Q. State whether or not the statement you were

making was for the purpose of releaving the tense

situation, if any ! A. Certainly if they knew what was

going—I always felt that if people know what is going

on, then they will know what steps to take, so I was

telling them what had happened, and I felt that this

was leading them, and one of the things I would have

advocated was that they all come together in a meet

ing later, a mass meeting of some type at church

or some hall here and we discuss plans to go out

and talk with the City officials, I feel that this would

have relieved the tension there, and we would have

all gotten together and left the area (R. 203).

Officer Carson told appellant that he could not continue

speaking without a permit (R. 42) and, when appellant

■continued talking, placed him under arrest (R. 43). Car-

son started to take appellant into the municipal building,

but appellant tried to pull back (R. 43, 205-06); Carson,

who outweighed appellant by 60 pounds (R. 35, 203),

testified, “ I finally manhandled him on up through the

door” (R. 43).4

After appellant’s arrest, the crowd was easily dispersed

(R. 68,78).

4 Once inside the police station, appellant fell to the floor and lay

there motionless (B. 207); he was picked up and carried to the

Sergeant’s desk for booking, after which he voluntarily got up (R.

207).

12

Appellant was charged with breach of the peace, in vio

lation of Miss. Code Ann. §2089.5 (1966 Snpp.), and with

resisting arrest, in violation of §252 of the Code of Ordi

nances of the City of Greenville. He was tried by a jury-

in the County Court of Washington County on September

16 and 20, 1963 and convicted.5 Appellant was sentenced

to pay a fine of $100 and serve a term of 90 days in the

city jail on each charge (R. 24-25; 145-46). Appellant’s

convictions were affirmed by the Circuit Court of Wash

ington County and, on June 13, 1966, by the Supreme

Court of Mississippi, 187 So. 2d 854.

On January 9, 1967, the Supreme Court of the United

States denied appellant’s petition for writ of certiorari,

three Justices dissenting, 385 U. S. 1011. Thereupon, ap

pellant filed the instant petition for writ of habeas corpus.

Specification of Error

The court below erred in holding that appellant’s speech

could be punished as a breach of the peace under Miss.

Code Ann. §2089.5 (1966 Supp.), consistent with the First

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States.

5 Earlier, on July 3, 1963, appellant was tried and convicted on

these charges in the Municipal Court of the City of Greenville.

13

A R G U M E N T

Appellant’s Speech Is Protected From Punishment

Under Mississippi’s Vague and Overbroad Breach of the

Peace Statute, Miss. Code Ann. §2089.5 (1966 Supp.),

by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Con

stitution of the United States.

Appellant was convicted on a general verdict of the

charge of “ disturb [ing] the public peace by loud or offen

sive language, or by conduct either calculated to provoke

a breach of the peace, or by conduct which might reason

ably have led to a breach of the peace” (R. 18, 24-25).

The court below held that the statute under which appel

lant was convicted, Miss. Code Ann. §2089.5 (1966 Supp.),

“proscribes only nonpeaceful speech, speech calculated to

cause or likely to cause a shattering of peace and order”

and accepted what it considered to be the state court’s

conclusion that appellant’s speech “ exceeded the bounds

of argument and persuasion and was calculated to or could

have led to a breach of the peace” (R. 249, 251; 279 F.

Supp. at 225-226).

The court below stated the principle enunciated by the

Supreme Court of the United States in Cantwell v. Con

necticut, 310 U. S. 296, 308 (1940):

The offense known as breach of the peace embraces

a great variety of conduct destroying or menacing

public order and tranquility. It includes not only vio

lent acts, but acts and words likely to produce violence

in others. No one would have the hardihood to sug

gest that the principle of free speech sanctions incite

ment to riot . . . When clear and present danger of

14

riot, disorder, interference with traffic upon the public

streets or other immediate threat to public safety,

peace or order, appears, the power of the state to

prevent or punish is obvious.

Appellant does not question the validity of this prin

ciple, but only its application by the court below.

Appellant contends that his speech was no incitement to

riot and that he was convicted under a statute “ sweeping in

a great variety of conduct under a general and indefinite

characterization, and leaving to the executive and judicial

branches too wide a discretion in its application” (Cantwell

v. Connecticut, supra, 310 U. S. at 308).

Appellant’s speech was no incitement to riot.6 It is true,

as the court below found, that appellant spoke in a “ loud

voice” (R. 243; 279 F. Supp. at 223). His speech was

directed to a crowd of about 200 people, most of whom had

been witnesses at the trial. His speech was critical of the

girls’ convictions; in effect, it “ denounced these convic

tions as ‘bad’ ” (R. 243; 279 F. Supp. at 223). The con

victions were bad. See note 3, supra. But the court be

low incorrectly found that appellant’s speech was “non-

peaceful.” Reliance for this conclusion was placed upon

certain of appellant’s statements which were characterized

by the court below as challenging the crowd with “what

they intended to do about it” (R. 243; 279 F. Supp. at 223).

In appellant’s speech of 8 or 9 minutes (R. 244; 279 F.

Supp. at 223), these statements were taken out of context;

viewed in its entirety, appellant’s speech was neither an

6 Because appellant is raising a claim of constitutional right in

the area of First Amendment freedoms, it is the duty of this Court

to make an independent examination of the whole record. Cox v.

Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 545, n. 8, and cases cited (1965).

15

explicit incitement—-nor a subtle invitation—to riot. See

pp. 3-7, supra. All that appellant urged his listeners to

“ do” was to register to vote so that illegal segregation

would end in Washington County.

In context, it is apparent that appellant’s speech did

not amount to the “ fighting words” condemned in Chap-

Unsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 (1942).7 Nor did

appellant’s speech amount to a case like Fein-er v. New

York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951), where “ the speaker passes the

bounds of argument or persuasion and undertakes incite

ment to riot” (340 U. S. at 321).8

The cases that are apposite are Edwards v. South Caro

lina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963); and Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S.

536 (1965). There, as here, the speaker intended to stir

persons in the crowd to action, viz., assertion of their

federal rights. Analysis of these cases reveals that ap

pellant’s speech merits no less federal protection than

that afforded the speech delivered in Edwards and Cox.

In Edwards,

the petitioners engaged in what the City Manager

described as “boisterous” , “ loud” , and “flamboyant”

conduct, which, as his later testimony made clear, con

sisted of listening to a “ religious harangue” by one of

7 The speaker in Chaplinsky met the following test developed by

the New Hampshire Supreme Court: “ The test is what men of

common intelligence would understand would be wrords likely to

cause an average addressee to fight. . . . The English language has

a number of words and expressions which by general consent are

‘fighting words’ when said without a disarming smile” (315 U.S. at

573).

8 The speaker in Feiner urged Negroes to take up arms against

whites (340 U.S. at 317).

16

their leaders, and loudly singing “ The Star Spangled

Banner” and other patriotic and religious songs, while

stamping their feet and clapping their hands (372

U. S. at 233).

The speaker in Edwards had “harangued” approximately

200 of his followers and at least an equal number of by

standers on the State House grounds in Columbia, South

Carolina. His and his followers’ breach of the peace con

victions were reversed by the Supreme Court, which held

that their constitutionally protected rights of free speech,

assembly and petition had been exercised “in their most

pristine and classic form” (372 U. S. at 235).

Cox had addressed a group of about 2,000 young Negro

students on the sidewalks between the State Capitol and the

courthouse in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. His was a speech of

protest (379 IJ. S. at 542-43):

[Cox] gave a speech, described by a State’s witness

as follows:

He said that in effect it was a protest against the

illegal arrest of some of their members and that other

people were allowed to picket . . . and he said that

they were not going to commit any violence, that if

anyone spit on them, they would not spit back on the

person that did it.

Cox then said:

All right. It’s lunch time. Let’s go eat. There are

twelve stores we are protesting. A number of these

stores have twenty counters; they accept your money

from nineteen. They won’t accept it from the twenti

eth counter. This is an act of racial discrimination.

17

These stores are open to the public. You are members

of the public. We pay taxes to the Federal Govern

ment and you who live here pay taxes to the State.

The Sheriff testified that, in his opinion, constitutional

protection for the speech ceased “when Cox, concluding his

speech, urged the students to go uptown and sit in at lunch

counters” (379 U. S. at 546), but the Supreme Court dis

agreed :

The Sheriff testified that the sole aspect of the pro

gram to which he objected was “ [t]he inflammatory

manner in which he [Cox] addressed that crowd and

told them to go on uptown, go to four places on the

protest list, sit down and if they don’t feed you, sit

there for one hour.” Yet this part of Cox’s speech obvi

ously did not deprive the demonstration of its pro

tected character under the Constitution as free speech

and assembly (379 U. S. at 546).

Appellant’s speech was, therefore, like the speeches pro

tected in Edwards and Cox a stirring and vigorous en

couragement to his listeners to assert their federal rights;

it was no invitation to violence.

Because appellant was convicted by a general verdict,

he may now stand convicted under one or more of the

following independent elements of the trial court’s charge

(R. 20-21):

1. “Disturb [ing] the public peace by loud or offensive

language” ;

2. “ Conduct . . . calculated to provoke a breach of the

peace” ;

18

3. “ Conduct which might reasonably have led to a breach

of the peace.”

Under settled principles, if any of these charges cannot

constitutionally be applied to punish appellant’s speech,

then his convictions9 must fall. Stromberg v. California,

283 U. S. 359, 367-368 (1931); Williams v. North Carolina,

317 U. S. 287, 291-293 (1942); Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S.

516, 529 (1945). Cf. Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382

U. S. 87, 92 (1965).

Appellant submits that none of these prohibitions is

drawn with the narrow specificity required to punish speech

of the kind which this record reveals. See Cantwell v.

Connecticut, supra, 310 U. S. at 307-11; NAACP v. Button,

371 U. S. 415, 432 (1963) and cases cited; Edwards v. South

Carolina, supra, 372 U. S. at 236-38; Cox v. Louisiana,

supra, 379 U. S. at 551-52; Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S.

479, 486-87 (1965); Ashton v. Kentucky, 384 U. S. 195, 200-

201 (1966).

There is a common infirmity running through these pro

hibitions punishing speech thought to be “ offensive” or

“ calculated to provoke”, or “which might reasonably have

lead to” , a breach of the peace. It is the conditioning of

the citizen’s freedom of speech upon the moment-to-moment

opinions of a policeman on his beat, thus “ allow [ing] per

sons to be punished merely for peacefully expressing un

popular views” (Cox v. Louisiana, supra, 379 U. S. at 551).

9 Appellant’s conviction for resisting arrest must fall with his

breach of the peace conviction because the trial court correctly

charged the jury that appellant could not be convicted unless he

was found to have committed a breach o f the peace in the arresting

officer’s presence (R. 142-43, 145). See Wright v. Georgia, 373

U.S. 284, 291-92 (1963); Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S

87 (1965).

19

This rationale was developed in Mr. Justice Black’s con

curring opinion in Cox, in which he condemned statutes

allowing a policeman to curb a citizen’s right of free speech

whenever a policeman makes a decision on his own

personal judgment that views being expressed on the

street are provoking or might provoke a breach of the

peace. Such a statute does not provide for government

by clearly defined laws, but rather for government by

the moment-to-moment opinions of a policeman on his

beat. Compare Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 IT. S. 356,

369-370, 30 L ed 220, 226, 6 S Ct 1064. This kind of

statute provides a perfect device to arrest people

whose views do not suit the policeman or his superiors,

while leaving free to talk anyone with whose views the

police agree.

The court below did not agree that Miss. §2089.5 allows

punishment of the peaceful expression of unpopular views

(R. 248-49, 279 F. Supp. at 225):

In the case here, the statute, as interpreted by the

state court, permits a conviction for speech only if

that speech was calculated to lead to a breach of the

peace or was of such a nature as ultimately led to a

breach of the peace. There can be no conviction for

peacefully exercising the right of free speech. This is

consistent with the principle that one may be found

guilty of breach of the peace if he commits acts or

make statements likely to provoke violence and dis

turbance of good order, even though no such eventual

ity be intended. Cantwell v. State of Connecticut,

supra. Under the statute here in question, so long as

the speech was peaceful—regardless of whether it in

20

vited dispute, brought about a condition of unrest or

stirred people to anger—a conviction was not war

ranted. (Emphasis in original)10

With deference, appellant submits that there can be a

conviction under §2089.5 for the peaceful expression of

unpopular views and that this is just such a case.

Appellant could have been arrested and convicted be

cause the arresting officer and the jury thought appellant’s

speech was “ loud or offensive,” even though “peaceful.” 11

Appellant could have been arrested and convicted be

cause the arresting officer and the jury thought appellant’s

speech was “ calculated to provoke a breach of the peace,”

10 The court below attempted to read §2089.5 consistently with

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 4-5 (1949) :

[A] function of free speech under our system of government is

to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose

when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction

with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger.

Speech is often provocative and challenging. It may strike

at prejudices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling

effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is why

freedom of speech . . . is . . . protected against censorship or

punishment . . . . There is no room under our Constitution for a

more restrictive view. For the alternative would lead to stand

ardization of ideas either by legislatures, courts, or dominant

political or community groups.

In Terminiello, convictions were reversed “ because the trial judge

charged that speech of the defendants could be punished as a breach

of the peace ‘if it stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, brings

about a condition of unrest, or creates a disturbance, or if it molests

the inhabitants in the enjoyment of peace and quiet by arousing

alarm’ ” (337 U.S. at 3).

See also Carmichael v. Allen, 267 F. Supp. 985, 997-99 (N.D.

Ga. 1967) (Three-judge court).

11 Appellant’s speech was no louder than necessary to reach a

large outdoor audience. A t any event, his speech could have been

punished as “ offensive” if the arresting officer and jury thought

it was too critical of the court’s decision. This alone would render

appellant’s convictions unconstitutional, see note 10, supra.

21

even though it is uncontroverted that appellant meant no

such thing (see pp. 4-7, swpra, and li. 109-10, 125, 202-03,

218).

Appellant could have been arrested and convicted be

cause the arresting officer and the jury thought appellant’s

speech “might reasonably have led to a breach of the

peace,” even though, under all the objective evidence,12

appellant did nothing more than invite dispute, bring about

a condition of unrest or stir people to anger—if that (see

pp. 7-11, supra).

Thus, this case is indistinguishable from and squarely

controlled by Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536, 551 (1965).

Cox voided convictions for speech conduct similar to ap

pellant’s under a Louisiana breach-of-the-peace statute that

is identical in its operative language to Miss. Code Ann.

§2089.5. The Louisiana statute was held facially uncon

stitutional on reasoning that plainly applies to and equally

condemns §2089.5. The District Court below sought to dis

tinguish Cox on the theory that the construction of §2089.5

by the Mississippi courts differed from the construction

by the Louisiana courts of the identical Louisiana statu

tory language (E. 248-249; 279 F. Supp. at 225). But, as

we have shown, the jury charge in the County Court au

thorized appellant’s conviction on grounds which are pre

cisely those condemned in Cox (see pp. 17-18, supra). The

Mississippi Supreme Court, in affirming appellant’s con

12 Appellant does not overlook the police officer’s testimony that,

in their opinion, violence could have erupted. But the federal

courts have not permitted speakers to be criminally punished simply

on the basis of hunches of police officers— however experienced.

See, e.g., Cox v. Louisiana, supra, 379 U.S. at 550. In fact, the

arresting officer testified that he arrested appellant because he didn’t

have a permit to speak (R. 42).

22

viction, did not distinguish Cox by purporting to construe

its statute differently from the Louisiana law there struck

down, but found only that the “ factual situation involved in

this case is entirely different . . . . • ’ 187 So. 2d at 860.

Whatever factual differences there may be— and we submit

that they are inconsiderable—appellant’s conduct, like

Cox’s, was entirely peaceful and non-inflammatory. If his

acts were criminal, they were so because Miss. Code Ann.

§2089.5 penalized incidents of them that were identical to

the incidents on which Cox’s unconstitutional conviction

also rested. This appellant has therefore been punished

in exactly the manner forbidden by Cox, under a statute

written, construed and applied in exactly the manner for

bidden by Cox. This conviction is illegal and must be va

cated.

From what has been said, it is obvious that appellant in

no way questions “ the right of a community to preserve

the peace and to protect itself from riots and disorder”

(R. 253; 279 F. Supp. at 226). But the City of Greenville,

no less than appellant, must heed President Johnson’s ad

monition upon signing the Civil Rights Act of 1968 that “ the

only real road to progress for a free people is through the

process of law and that is the road that Americans will

travel” (New York Times, April 12, 1968). Uncomfortable

as it may sometimes make police officers on their beat, we

cannot retreat from our “ profound national commitment to

the principle that debate on public issues should be unin

hibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include

vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp at

tacks on government and public officials” (New York Times

Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254, 270 (1964)).

23

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, appellant prays that the

order of the district court denying appellant’s petition

for writ of habeas corpus be reversed and the case re

manded with directions that the writ be granted and ap

pellant discharged.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack G-reenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

R euben V. A nderson

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

R. Jess Brown

125% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Appellant

24

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that on April 1968, I served a copy

of the annexed Brief for Appellant npon J. Bobertshaw,

Esq., attorney for appellee, P. 0. Box 99, Greenville, Mis

sissippi 38701, by United States air mail, postage prepaid.

Melvyn Zarr

Attorney for Appellant

RECORD PRESS — N. Y. C. <^g^> 38