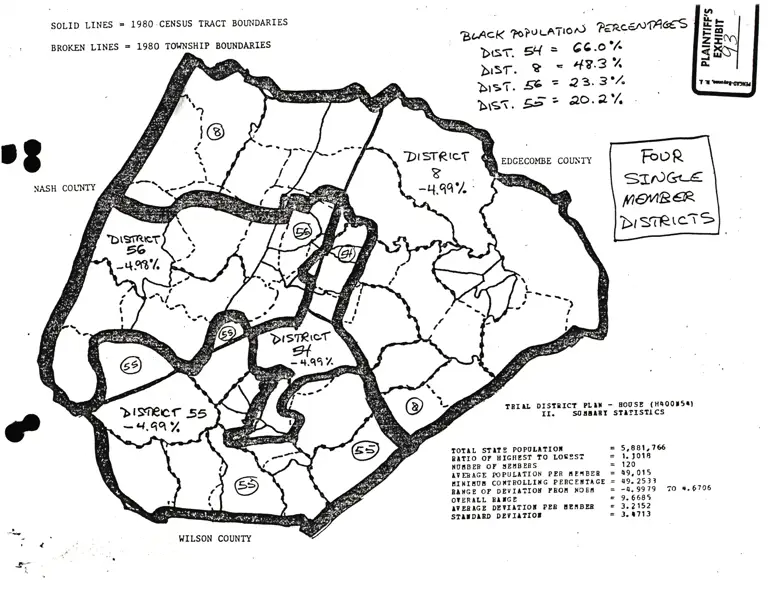

Plaintiff's Exhibit 93

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1984 - January 1, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Plaintiff's Exhibit 93, 1984. d7d0613b-d592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/385de82c-4c95-4c22-ad64-7ac18b4a5da6/plaintiffs-exhibit-93. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

SOLID LINES ' 1980'CENSUS TMCT BOTNDARIES

BROKEN LINES = 1980 TOWNSHIP BOTNDARIES

NASH COL'}ITY

?,.,/{cK ?oluLATrod ?anq€^)ffic{s

D6-r. 5q = CC.o'/.

!rSf. 3 !B tt8'3'A

brsT. SG = 23' 3'/"

brs(.952 ao'?'A

,3 EDGECO}EE COUI{IY

TSIT"L DISIBICT PLIT '

II. SOtllBr

FoR

33P@<--€

ftgnEe.

DrsnRtciS

EOOSE (Htl00l5rl

srlltsrrcs

torll. srllg POPoLI?ror

Bttro or ETGREST tO LOSgSi

IIOIBEB OP IEUBEES

IVISAGE POPUTITIOH PER ltEt8E8

TIIIIIUI COTTBOLLIXG PEBCEIl^GE

BTIIGE OT DEYIA?IOX ?BOII XCEI'

OTSRILL EIIGE

IYESIGE DEIIATIO' PBB IEiBAB

sllrDIBD DtrIrrlo,

5,8Itr766

r. ,018

r20

t9, 0t 5

09. 253 l

-q. 99 79 iO .. 6706

9.6685

3.2 152

3. r7l3

F

lgrtr

I tr-

Fz

(

-IA

rr'

DISTRIcT

8

\,

t

l-'- --t,

,

I

\ \

,

brgrntcT

5C

-{.qx%

t']

a?

DrsrRrsfe{

>rsftc.. s5

- cr. qqy.

T{ILSON COUNTY

tEtEEBS

t8rlr, DlsTsrct PLtt - Bo{rst (E400r5fl

1.. Lrsl ol ErrllrEs Bt DrstBlct SIIE PoPt [llrols

DISfPOP = FOPULIfIOX OP fEB DISTnIef

8EL DEr = BELI1IVE DEVIIffOf

BLIG_P=PEBCETI BLICTS TT DTSTEICT

IIDIAf,_P=PSBCEIt IlDIlrS Ir DISTBICT

POP = FoPULITIOX OP I COUrlfr loEllSEIP, ETC.-

DISTFOP

i5 r565

BEL-DIY 8LICf,-P IIDIIT-P

,3

-f.9979 e8.3 0.t

ETTITI

EDGECO!BB COUttt

rP 1 (rB8 rR 208P

TP I TtaB tn 209

rP I TIBB ?8 210

TP I ITBB IB 2I T

rP t tlEB ta 212

tP I llBB T8 2l3P

TP I T CTT TB 213P.

IOTXSErP 2, LOrEB COrE

TOEESEIP 3, SPPEE COXE

ao9rsElP q. DEEP CBEEf,

roSrsEIP 5, LorBB PISH

TOSilSBTP 6, OPPER PISE

STIFI C8 TB 2O5P

rP 8 SPIBT TB 2T3P

TP 8 SPTBI TB 2I6P

?oYilsBIP 9, OrrBB CRBE

rocls8lP 10, LOIEB tor

TOITSEIP tl, BtLf,Ol CB

RI' TIP TB-2T3P

toBxsErP 13, coxEr

osc TrP ED-1222

utc r9P ED-1225

tlsE courrI

ctsrllrt roSf,sEIP

GBTF TIP ?8 IOSP

6BIT ITP TB TO9P

ilrt TrP tB t09P

XISE TTP TB IOSP

rASE TIP IE IOgP

r TEIT TIP T8 1O7P

r TEII TTP 1B IOSP

8ED OIX AOTISEIP

S TEIT TTP ED 972

S SETT TYP TE 1 O7P

S TEIT TflP T8 IOSP

S1OTT CBf, TTP IOTP

sfotr cBf, TrP t08P

EDGECOTBE COUtrIT

srlrr ca T8 205

Bf, Crr ?rP-20 t

Br cTr t',P.202P

Br cIt TrP-203P

8r crt rrF-2oqP

Bt frP ta-202P

BT TTP I8.2O3P

tr ttP rt-200P

31,892

t86

3,4f1

3, ggg

3.132

'.3,962

38f

t7

1.7 29

953

986

l, ff3

1,78t

2.571

782

603

1,83 t

3,253

l,2q0

l,lq0

1t267

1t

308

1 1,673

1t328

87

2. l6tl

3r3

293

32t

t, 589

896

1.773

lf

1,316

652

350

517

21.096

636

Ito t

5,035

4.57 6

5r 066

908

588

752

t

1

5r 6.57O -1.9077 66.0 0.t

Drst tEtBars DISTPOP IEL-DA' al.lctr_P

TIIIL DISIIIC' PLIT - EoESr (Eroor5ll

161565 -{.9979 20.2

rlDrrI_P rtrrrt

8t tIP in-2ttP

utrc trP ,,D_1223

utc trP Bblz2a

Irsc T3P ED_1226r

tlsE colrtlt

rt cTt l02P-Bc1

Bl crI 102P-ac2

tt clI !02P-BG3P

8t ctr t02FBLt0t

Bt c?l lo2P.BLtO2

Br ctf t02P-BLe03

8t erl t02P-8Lt0tP

Bl cft t02FBLfo5

Bt crl t02P-81t06

rt ctt t02p-8t't07, tr ctr lo2P-BLto8

rr cft to2P-BLtt3

Ir clr to2P-BLttt

8t ctr t02P-8L{t5

Ir qrr l02P-8Lt16

Bt crr l02P-8Lt t7

nt ctr l02P-BL|t8

nt crt to2P-BLf20

8t eft to2P-BLq2t

. Bt cft to2P-BLt22

8f, Crr t02P-BLr23

Bi cr 1029 RL a29P

tt cr 102P BL f30

trtr,sor coortr

GTBDIBE rgP BD 7I3

rorstct trP BD 700

torstol trP BD 701

torstot IrP ED 702

rorsrot tP tD 703t

tolsrot lP 8D 7038

sILSol trP tD-7351

trlsol rrP BD-7391

TILSOT Ctr trP-2

rrLsot cl tP aI.l22

TILS CTT OP-BLI23

IILSO' CI IP ELI2I

rrlsot ctl trP-?P

rrLs ctr ttP-8-0t

rrls c?r rrP-&o2P

0. , rlSE Cotrttr

BITLET TOTISEIP

artcf,s tfP 8D t05t

IILSOT COUrtr

BLICr c8E!f, ?OCISETP

c80ss BolDs TortsEIP

e lEDrBR trP 8L 7ltl

GIBDXBB ITP ED 7E2

GIIDIEE T'P ED 7{I

oLD ?rtlDs totrstlP

Ir

PO?

t28

32

27

807

6t07 3

1"580' 1,397

2.179

l2

tt

t09

209

t7l

23

33

,29

29

t9

t3

l2

l6

28

65

t9

38

75

o

o

t9, fo I

2t2

,25

tr55t

988

tr905

o

291

It2t

1.926

o

2l

o

6,29O

3.717

lr7lg

2.831

2.517

287

13,73 |

2.971

3,075

853

1.823

o

3,35t

'.c

55

Drst tarBtBs

ItIIf, DISTBICT PLII . EOITSB (E000r5tl

DI:'TFOP BET.-DEI BLICf,.P TTDIII-P EI?I?T

,3

stEltoct tortsEIP

SP[I'GBILL ?OTTSEIP

srtDTof,s zD-7ugt

sltx1ors BD-750r

slrf,Tots ED 7508

srrrtors BD-751

srtf,toxs BD 752

IIILOB TOTTSBIP

torsrot lP ED 700

lrl.so[ TltP ED-l27

TILSOI.TTP ED-?28A

IILSOX.TTP BD 728C

rILSOI TBP BD-7297

fILSOt taP BD 729C

ITLSOII TAP ED 7298

crlsor TaP Eo 729a

CILSOT TTP ED.73O

trl.soI TrP ED-731r

TILSOX T3P ED 73IC

TILSOf, T8P ED 732A

SILSOU TIP ED-732C

TILSOII TCP BD 732D

IILSOI Tl,P ED 7328

TILSOX T8P ED-733

TILSOT TTP ED 730

TILSOX .TTP ED 735

IILSOX .TTP ED-736C

TILSOII TTP ED 736G

TILSON TTP ED 736J

SILSOI TCP ED 736L

TILSOf, TTP ED-737

TII,SOf, TIP ED-7387

IILSOT TIP ED 739C

'ILSOf,

T[P ED.?EO

TILSOT TTP BD 7668

IILSOI CTr tSFl

TILSOX Crr !EP-3

3ILS ClI {P.BGTP

rrl,s clr iP-BG2

IILS Ctr iP-8Lq0t

,rLsotr cr 8P BLt02

rILS CTI IP-ELIO3

IILS Ctr lP-BL{or

rrl.s crr qP-BLtos

trls elr 0P-BLtr06

crl,s cTr {P-8L007

lrls cTr tP-8Lll08

IILS CTT qFBLOO9

trls cTr fP-BLo t2

TILS CTI {P.BLC13

IILS Crr 0FEL| trt

TILS CTT BP-BL415

TILS CTT IP-BLq 16

rILs etr iP-BL0 17

IILS grr tP-BLqt8

2.192

2.064

920

6t0

0

90

o

2.328

t8t

tfl

791

0

266

0

.0

0

2

2

0

0

I

0

0

2

0

0

6

0

0

0

t

771

0

2t5

0

q,589

2,562

1.621

lr 5{0

3f5

0

32

69

t5

I

7'l

58

r55

6t

62

r6

t0

It5

t9

32

D

,rsr IEIBEBS DISTPOP 8 EL-DSY BLICf,-P ITDIAI-P BrII?T POP

l8

23

9

217

0

5

5, 106

3,95t

It6,573

2.108

2,354

1, q39

tr505

201

3.7 l9

609

tllt

5,535

3,0tl9

f88

't3

5t

80

23

6

3,095

tI,359

661

2

0

23

92

72

t35

098

35

3q8

2t

7

19t

58

I

20

402

132

570

92

8

0

367

09

l9

'l

89

tr?0t

8.537

3,olt t

46,573 -0. 98 16

I 46,573 -rt. 98 t6

rBIII DISTBICI PI.IT - EOrrsB (Bll00r501

TILS gTT 4P-BLS19

rILS gll OP.BI,I2O

TILS CTI 4P.8L421

rrl.s ctr 4?-8L129

rrl,sor cr 4P 8L430

TILS CTT IP-BLO3I

STLSOX Clr rrP-5P

TILSOX CTI T3P-6P

ltsE courTr

cooPEns ro8ISErP

DRT IELI,S TOCHSEIP

FEBBELLS TOTf,SEIP

JICf,S TTP BD T13P

JTCXS TTP ED 115P

trr[ lnP rB t loP

rrrx lrP TB tttP

lrf,l r3P rR I l3P

ltsE trP rB lltP

OAK LEYEL TOTTSBIP

Er cTt T8P-101

f,f, clr l02P-8L409

nt cTr 102P-BL4l0

8t err lo2P-BLrttl

8t srr to2P-BLlt2

Br crr l02P-BLI19

Bt ctl T8P-t03P

Bt ctr rrFt00

8r rrP ED-1017

Br rrP ED-10t8

BI TTP BG 3P

8E tTP BG q

8r Trp 8D-1019

BI TBP ED.IO2O

BI TIP BIFTO2I

nr rrP BD-t022

BI TTP ED-T023

nlt TrP BD-l02gr

BI TIP ED-I025

BI TIP BD-I026

Br trP ED-t027

NH TTP ED-I028

BI TTP ED-1029

Br rrP ED-t030

BI T'P ED-IO3I

BI TTP ED-1032

nr rrP ED-1033

nr T3P BD-103q

n! TrP ED-t035

BT TTP ED IO93B

s 3[r? TrP 8D 973

S TEII TTP BD 97IT

S

'EI?

lTP ED 975

S TEII TCP BD 976

S gEII TCP TB IO6P

s?otl c8K tIP t,03P

srorr cBr TrP t05P

5TOII CIT TTP IO6P

56 23.3

23.3

0.,

0. I

,I

56