Clark v. Kraftco Corp. Court Opinion

Unannotated Secondary Research

August 26, 1971

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Working Files. Clark v. Kraftco Corp. Court Opinion, 1971. fc7e51b8-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/395dbb54-6965-4578-aea5-e93600a26b1a/clark-v-kraftco-corp-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

r

■ I ■

'&& ■

y ~*‘':''''. S ̂ l f .» w v;e~'

. ■■ ■ ■

933

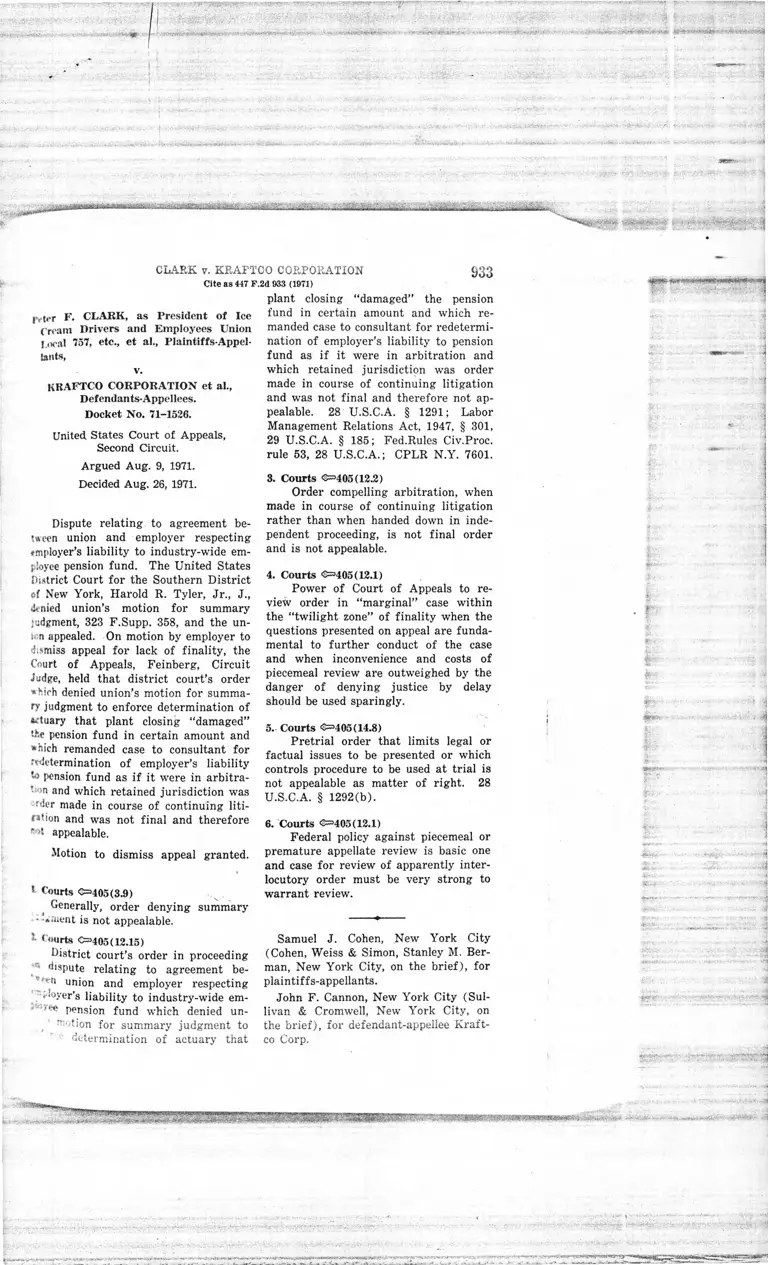

Ivt(»r F. CLARK, as President of Ice

(’ream Drivers and Employees Union

| , K.al 757, etc., et al., Plain tiffs-Appel

lant*,

v.

KRAFTCO CORPORATION et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Docket No. 71-1526.

United States Court of Appeals,

Second Circuit.

Argued Aug. 9, 1971.

Decided Aug. 26, 1971.

CLARK v. KRAFTCO CORPORATION

Cite as 447 F.2d 933 (1971)

plant closing “damaged” the pension

fund in certain amount and which re

manded case to consultant for redetermi

nation of employer’s liability to pension

fund as if it were in arbitration and

which retained jurisdiction was order

made in course of continuing litigation

and was not final and therefore not ap

pealable. 28 U.S.C.A. § 1291; Labor

Management Relations Act, 1947, § 301,

29 U.S.C.A. § 185; Fed.Rules Civ.Proc.

rule 53, 28 U.S.C.A.; CPLR N.Y. 7601.

Dispute relating to agreement be

tween union and employer respecting

employer’s liability to industry-wide em

ployee pension fund. The United States

District Court for the Southern District

of New York, Harold R. Tyler, Jr., J.,

denied union’s motion for summary

judgment, 323 F.Supp. 358, and the un-

i< n appealed. On motion by employer to

dismiss appeal for lack of finality, the

Court of Appeals, Feinberg, Circuit

Judge, held that district court’s order

*Mch denied union’s motion for summa

ry judgment to enforce determination of

actuary that plant closing “damaged”

the pension fund in certain amount and

*Hich remanded case to consultant for

^determination of employer’s liability

to pension fund as if it were in arbitra

tion and which retained jurisdiction was

rder made in course of continuing liti-

L»bon and was not final and therefore

* 4 appealable.

3. Courts <3=405(12.2)

Order compelling arbitration, when

made in course of continuing litigation

rather than when handed down in inde

pendent proceeding, is not final order

and is not appealable.

4. Courts <3=405(12.1)

Power of Court of Appeals to re

view order in “marginal” case within

the “twilight zone” of finality when the

questions presented on appeal are funda

mental to further conduct of the case

and when inconvenience and costs of

piecemeal review are outweighed by the

danger of denying justice by delay

should be used sparingly.

r -

5. Courts <3=405(14.8)

Pretrial order that limits legal or

factual issues to be presented or which

controls procedure to be used at trial is

not appealable as matter of right. 28

U.S.C.A. § 1292(b). m .

Motion to dismiss appeal granted.

! Courts <3=405(3.9)

Generally, order denying summary

• *.uent is not appealable. 1

1 Courts <3=405(12.15)

District court’s order in proceeding

dispute relating to agreement be-

union and

6. Courts <3=405(12.1)

Federal policy against piecemeal or

premature appellate review is basic one

and case for review of apparently inter

locutory order must be very strong to

warrant review.

employer respecting

-lover’s liability to industry-wide em-

<‘ ■ •0 pension fund which denied un-

Samuel J. Cohen, New York City

(Cohen, Weiss & Simon, Stanley M. Ber

man, New York City, on the brief), for

plaintiff s-appellants.

John F. Cannon, New York City (Sul

livan & Cromwell, New York City, on

•fT"'

.V - ’ "*■* V f-.< r . •*’-■¥ '.^ s k* ;?s^ ‘-.-*s.;>.-

. v, ;: -

931 447 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

.Before FEINBERG, MULLIGAN and

TIMBERS, Circuit Judges.

FEINBERG, Circuit Judge:

This is a motion by appellee Kraftco

Corporation to dismiss the appeal of Ice

Cream Drivers and Employees Union Lo

cal 757 and Milk Drivers and Dairy Em

ployees Union Local 680 1 from an order

of the United States District Court for

the Southern District of New York,

Harold R. Tyler, Jr., J., 323 F.Supp.

358, denying the Locals’ motion for

summary judgment in a breach of

contract suit under section 301 of the

Labor Management Relations Act, 29 U.

S.C. § 185. For reasons explained be

low, we agree with Kraftco that Judge

Tyler’s order is not “final” under 28 U.

S.C. § 1291 and, therefore, dismiss the

appeal.

The background of this motion can be

briefly stated. Kraftco and Locals 757

and 680 signed an agreement, dated

April 25, 1968, respecting the planned

closing of Kraftco’s Breyer Ice Cream

Plant in Newark, New Jersey. Among

other things, the agreement provided

that the actuarial consultant to the in

dustry-wide pension fund would deter

mine the impact, if any, of the closing

of the Breyer plant and that, if the pen

sion fund was found to be adversely af

fected, Kraftco would pay to the fund an

amount determined by the consultant.

About 18 months after the agreement

was signed, the consultant determined

that the liability of Kraftco to the pen

sion fund was $978,100. After Kraftco

refused to pay that amount, the Locals

instituted this suit.

In the district court, the Locals moved

for summary judgment on the grounds

that the agreement made the findings of

the consultant final and binding on

Kraftco and, in the absence of fraud or

misconduct, the court could not go be-

I. Both Locals are affiliated with the In

ternational Brotherhood of Teamsters,

Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers

of America.

hind those findings. The district court

did not agree and, relying primarily , ,

its finding that the parties did not in

tend to allow the actuarial consultant ? ,

resolve ambiguities in the contract. d,

nied summary judgment. In additi. ■

the court set aside the findings of

consultant, remanded the case to the con

sultant for redetermination, pursuant ;

N.Y.C.P.L.R. § 7601, of Kraftco’s liabili

ty to the pension fund, and ordered that

the consultant’s report include finding*

as to certain specific matters. From tin*

order, the Locals filed a notice of appeal

[1] The Locals recognize that goner

ally an order denying summary judg

ment is not appealable. They point out,

however, that the district court not only

denied summary judgment but also \a

cated the consultant’s determination, set

aside and reformed the contract sued

upon and sua sponte compelled arbitra

tion. Essentially, the Locals present

two theories supporting appealability

First, relying on Goodall-Sanford, Inc. v

United Textile Workers, 353 U.S. 550, 77

S.Ct. 920, 1 L.Ed.2d 1031 (1957), they

argue that Judge Tyler’s order is ap

pealable because it compelled arbitration

in a section 301 suit. Second, citing Gil

lespie v. United States Steel Corp.. ■

U.S. 148, 85 S.Ct. 308, 13 L.Ed.2d 19V

(1964), they contend that the order

appealable under a practical construction

of finality. This is so, they contend, L

cause the order denied them the only , 1

lief they sought, the recovery of the sum

determined by the consultant, and !-

cause the expense and delay invo vn, .

the remand to the consultant out .vi-ivi*

the inconvenience and cost of a P" *’

meal review.

[2] As to the first argume.a. ̂

Locals assume that Judge Tyler

can properly be regarded as thou*n •

were an order compelling arbitiM

2. As stated above, the remand to the ■

arial consultant was jiursuant to N- -

. L .R . § 7601 “as if it were an arbitrm

In addition, Judge Tyler order,’ i

V g j ' S f n p j r a " W i » S -1». >- » ■' r 5- -* -j %■-•-• .v ' " -* •:- "i'4'-.' jsvsy

':. , V •' r ■ ■ ■ ' ' ' - . ; •

—"«> Jr-**'%■-■-■• 4 ® ai& nss-a***>.»*c- -• r . jS s r - ^ 'V ^ r ^ ? .< ' ,»*-

;vif | &••' - /

'■. y%̂?eA) .afojfy •. &.?« Spjfe '-'- ~- iL w- p • w * -• . -c -v »* ;

■

.. ^wif ̂ *®®*** ~v«&- &»-.c.-i

- ’

CLARK v. KRAFTCO CORPORATION

Cite ns 1ST F :

- ; ;: hv no means clear.' The contract

nv.t provide for arbitration and nei

ther party requested it. Thus, Kraftco

4f(,ups that Judge Tyler did not reform

contract sued upon and turn it into

in agreement to arbitrate. Doubtless

(he situation before us is an unusual

.„.. and Judge Tyler’s order is a hybrid.

While the Locals’ characterization of the

vtder is certainly not far-fetched, the

r,jer also resembles a district court re

versal of findings of a referee with a

n-mand to him for further findings, for

which Kraftco cites Bass v. Olson, 327

y 2d 662 (9th Cir. 1964) and Hillcrest

Lumber Co. v. Terminal Factors, Inc.,

ZM F.2d 323 (2d Cir. 1960). Such a

reference to a master would not ordi

narily be regarded as final. See 5 J.

Moore, Federal Practice UK 53.05[3], 53.-

!3[3] (2d ed. 1970); cf. 1966 Amend

ment to Fed.R.Civ.P. 53 (expanded the

term “master” to include “assessor”).

935

•ubjeet to waiver by stipulation of the

thirties,” the determination on remand

k* attended by the formalities which

formally accompany an arbitration under

•Article 75 of the New York Civil Practice

fj)w and Rules.”

• >imilarly inapplicable is the confusing

• o«> of eases concerning whether an order

. • ' i ' .• *

f** * W r ’«*» • AW*** , -:

d i-:yd. aorn . •

compelling arbitration when made in the

course of a continuing litigation ra ther

than when handed down in an independ

ent proceeding is not a final order.

Chatham Shipping Co. v. Fertex S.S.

Corp., 352 F.2d 291, 294 (2d Cir. 1965);

Farr & Co. v. Cia. Intercontinental De

Navegacion, 243 F.2d 342, 345 (2d Cir.

1957). See Rogers v. Schering Corp.,

262 F.2d 180, 182 (3d Cir.), cert, denied

sub nom., Hexagon Laboratories, Inc. v.

Rogers, 359 U.S. 991, 79 S.Ct. 1121, 3

L.Ed. 980 (1959).3 As Judge Tyler

has retained jurisdiction over this suit

and further action by him on the merits

is necessary, the order appealed from is

one made in the course of a continuing

litigation. Therefore, even on the ques

tionable assumption that Judge Tyler’s

order is the same as the more usual or

der directing arbitration, we conclude

that it is interlocutory rather than final.

[3] On the assumption that the or

der directs arbitration, it is true that

«uch an order, while seemingly interlocu

tory, may be appealable in certain cir

cumstances. But even on that assump

tion. the Locals have overstated the

M-ope of the Goodall-Sanford decision.

That case was an action under section

*91 to compel specific performance of an

arbitration provision in a collective bar-

raining agreement. In that context, the

Supreme Court, reasoning that the arbi

tration was “not merely a step in judi

cial enforcement of a claim nor auxiliary

*o a main proceeding, but the full relief

*‘>ught,” held that a decree ordering a

•W ific performance of the arbitration

J revision was final within the meaning

*f 23 U.S.C. § 1291. 353 U.S. at 551-52.

’u the language just quoted indicates,

- '*ever, that decision does not change

’-‘e rule of this circuit that an order

ipra. All that

ie was <

the'power to review an order f

H H N H R H B S S Bof finality^* where the questions presen'

W rm w m M H i

further conduct of t

inconvenience and costs of piecemeal re-

refusing or granting a stay pending arbi

tration is an appealable interlocutory

order under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a). See

the thorough analysis of these decisions

in Standard Chlorine, Inc. v. Leonard, 3S4

F.2d 304 (2d Cir. 1967).

«e wWHk* ~S

4»«i 4

r

A.

.. . a

A'-.... 4

t: . 4

1

■1

-1

■5

no

- ■ • • •>-*****«•»*. -v , . • .. . • ■-*«

......• ...... .•.<>>• -tM

i ;jsc W. 7_~~ -nr«i i—

* V j&g , it. w«- ••-/*»- + •-*&#* " g !

■

- w?***** w*******̂

» '•■ '.S|„ ,-Ji,*piS«rl»V •»*' * < - :

__■■ .-. ■ —____ .__

~»*- '#SL *,.*»■

936 447 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

tig rang irT"ffTir.n̂ ^̂

[5] Judge Tyler did not rule that

Krafteo had no liability under the

contract. Rather he decided that on

one particular theory of the law and

facts such liability could not be found

and ordered “further proceedings”

under Fed.R.Civ.P. 56(d). This does

not differ appreciably from a pre-trial

order that limits the legal or factual

issues to be presented or controls the

procedure to be used at trial. Such

an order is not appealable as a matter of

right. Cf. 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b). It is

true that the Locals will incur expense

and delay as a result of the order below,

but probably no more so than had Judge

Tyler simply denied summary judgment

on his construction of the contract and

provided that all the issues should be

tried in the district court in the first in

stance rather than remanding some of

them to the consultant. No doubt the

Lpcals would say that such a course

would also have been uncalled for under

the contract, but the correctness of an

order does not ordinarily determine its

finality. In that event, the Locals would

still have been “required to bear the

costs of witness fees, appraisers’ fees,

4. Memorandum of Plaintiffs-Appellants in

Opposition to Motion to Dismiss Appeal

at 22.

5. The Locals also rely on Plymouth Mutual

Life Insurance Co. v. Illinois Mid-Conti

nent Life, Insurance Co., 378 F.2d 389

(3d Cir. 1907), where an appeal was al

lowed from a post-judgment order modify

ing a judicially-approved settlement agree-

attorneys’ fees, [and] a., stenograph*

transcript,” expenses which they r ,<

urge as justifying appealability.4 •

Moreover, unlike Gillespie, interest# <

judicial efficiency will not be served <

allowing the appeal. Neither side hi..-

briefed the basic substantive issue#

appeal and we, obviously, have not r

sidered them. Indeed, allowing the a;

peal at this time rather than after th

district court makes an award, if am

may very well result in the needless < t

penditure of judicial effort. Even \ver<*

we to reverse Judge Tyler’s order, v>

could not grant full relief to the Local'

because Krafteo raises the issue, r. ■*.

passed upon by Judge Tyler, that unit -

the Locals’ theory, the consultant's im

port contains clear errors totaling a#

much as $500,000.5

[6] The federal policy against pieo

meal or premature appellate review is *

basic one, embodying several important

considerations. See American Exprwi

Warehousing, Ltd. v. Transameriea h-

surance Co., 380 F.2d 277, 280 (2d (it

1867). In light of this policy, tic

case for review of this apparently int<-

locutory order must be very strorv

While the Locals’ arguments have I>«p

presented persuasively, they are not >u'

ficient to carry the day. We era- *•

Kraftco’s motion to dismiss the applet

for lack of finality under 28 U.S.C I

1291.

ment. However, the court there eui|>M

sized that since a post-judgment order

involved, “the policy against and the I>r- ’

ability of avoidable piecemeal review an

less likely to be decisive after judgim-i**

than before.” 378 F.2d at 391. At n>**

the case indicates that “it is someone-

appropriate” for practical reasons to f “

the technical rules of finality. I ■

we do not think that this is such a 1

; . ■

• . • •