Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

April 22, 1975

99 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc, 1975. b54f6bdc-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/39e56193-5901-4eb4-b4b5-d410c49617cc/carr-v-montgomery-county-board-of-education-petition-for-rehearing-and-suggestion-of-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

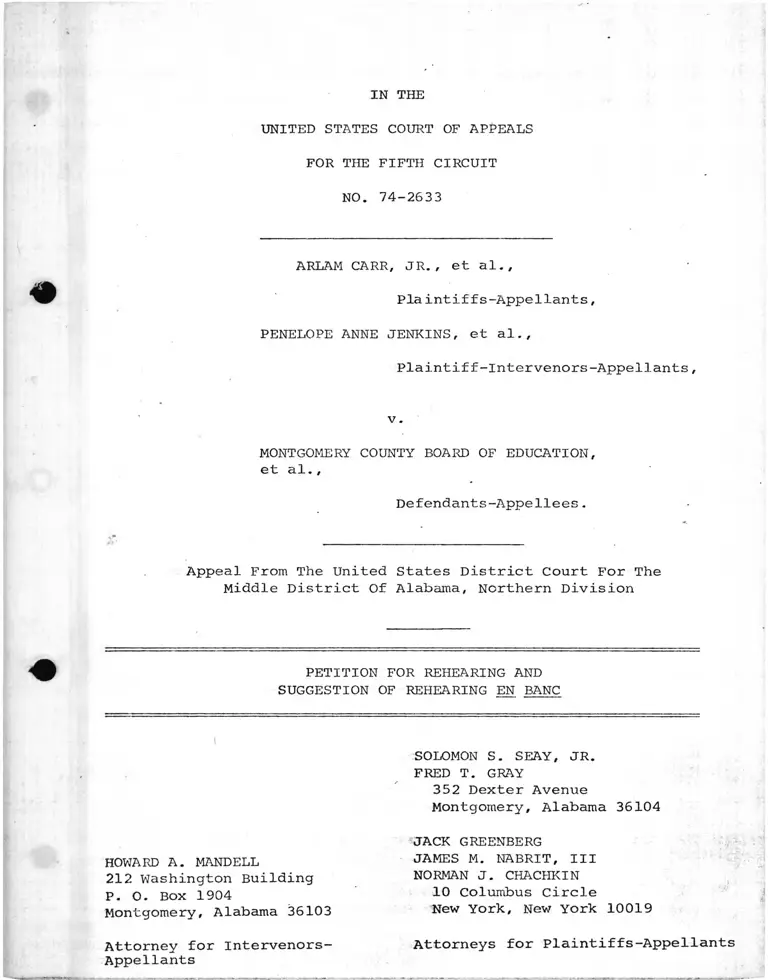

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-2633

ARLAM CARR, JR., et al.,

Pla intiffs-Appellants,

PENELOPE ANNE JENKINS, et al.,

Plaintiff-intervenors-Appellants,

v.

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Middle District Of Alabama, Northern Division

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND

SUGGESTION OF REHEARING EN BANC

HOWARD A. MANDELL

212 Washington Building

P. O. Box 1904

Montgomery, Alabama 36103

Attorney for Intervenors-

Appellants

SOLOMON S. SEAY, JR.

FRED T. GRAY

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-2633

ARLAM CARR, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

PENELOPE ANNE JENKINS, et al.,

Plaintiff-Intervenors-Appellants,

v .

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Middle District Of Alabama, Northern Division

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND

SUGGESTION OF REHEARING EN BANC

Appellants, by their undersigned counsel, respectfully pray

that, pursuant to F.R.A.P. 40 and 35(a), this Court grant rehearing

en banc of the April 11, 1975 decision by a divided panel in this

case, for the reason that the majority approves (without reserva

tion, comment, or explanation), clear legal errors by the district

court which place this ruling in complete and irreconcilable

conflict with the vast majority of this Court's school desegregation

decisions since at least 1969.

Not only is the result in this case contrary to principles

long thought settled in this Circuit, but the reasoning of the

district court's opinion (apparently approved by the panel

majority) was completely rejected, on the same issues, by the

same panel, in Flax v. Potts, 464 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 409 U.S. 1007 (1972). See, for example, Judge Goldberg's

dissenting opinion at pp. 17a, 20a n. 15, 27a n. 18, 28a, 35a

n. 25, 37a n. 26, infra. Thus, not only will this opinion result

in further delaying desegregation of the Montgomery County,

Alabama school system, but it will also mislead lawyers and lov/er

courts in this Circuit to believe that Fourteenth Amendment

principles have been changed.

Appellants believe that Judge Goldberg's comprehensive and

dispassionate dissent establishes the need for rehearing en banc

with greater clarity and persuasiveness than anything we could

write. And we have no desire to burden the members of this Court

2/

with additional volumes of material to read. The length of the

1/ ' .

1/ The one-paragraph per curiam opinion affirming on the basis of

the district court's opinion, is attached hereto at p. la. Judge

Goldberg's dissenting opinion is attached at pp. 3a-45a. The dis

trict court's opinion follows at pp. 57a-86a.

2/ There have already been filed in this matter plaintiffs-

appellants' 17-page Motion for Summary Reversal, accompanied by a

lengthy Appendix of important documents and lower court rulings; the

School Board's 12-page response thereto; plaintiffs-appellants'

60-page Brief on the merits (with an appendix of selected exhibits

and tables; the intervenors-appellants' Brief on the merits of 70

pages, with appendices; the Brief for the United States amicus curiae

[continued on next page]

2

documents previously filed in this case results from its

3/

procedural and substantive complexity. However, Judge Goldberg's

dissenting opinion provides a fair, yet brief, capsule summary

4/

of the factual highlights at pp. 3a-lla, infra.

Despite this complexity, the several errors of the district

Vcourt are glaring and capable of concise summarization. Each,

standing alone, would be sufficient to warrant reversal of the

district court's judgment. Together, they present an appaling

picture of constitutional retrogression. The district court's

rulings cannot be squared either with the consistent thrust of

6/

school desegregation jurisprudence in this Circuit since Jefferson,

V 8/or with the Supreme Court's mandates in Swann and Keyes. Indeed,

2/ (Continued)

in support of Appellants of 51 pages; and the School Board's

Brief of 67 pages and appendices.

3/ For example, the "plan" approved by the district court is

actually a series of several submissions and modifications of

earlier submissions at the instance of the court.

4/ A very detailed statement of the case and description of the

relevant facts is found in the Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants at

pp. 4-33 and the Brief for Intervenors-Appellants' at pp. 3-32.

5/ They roughly correspond to sections II A, B, and C of the

Dissenting Opinion, infra, pp. 12a-43a.

6/ United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372 F.2d 836

(5th Cir. 1966), aff'd en banc, 380 F .2d 385, cert. denied sub nom.

Caddo Parish School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967).

7/ Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971).

8/ Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).

3

it is of little comfort to Montgomery's black school children that

the Supreme Court has authorized Judge Johnson to protect his

desegregation decrees by issuing injunctions against private

9/schools' use of city recreational facilities when those decrees

themselves are so virtually valueless, in terms of bringing about

actual desegregation.

The district court allowed numerous elementary schools and

several junior high schools to retain forever their all-black,

or virtually all-black, character because (a) it held there were

only a few such schools — the "small number" permitted by Swann;

(b) the Court said these enrollments resulted from residential

patterns independent of school board actions; and (c) no practicable

remedy existed to desegregate these facilities, both because the

achievement of that end would require inordinate busing and because

attempts to attain the goal by transporting white students to

historically black schools would not result in lasting desegrega

tion. To the extent that these holdings might be defensible if

adequately supported by specific factual findings, they are

weakened beyond credence by the total absence of relevant fact

finding by the district court. To the extent that they enunciate

principles of law independent of particularized factual situations,

they have been held wrong in countless opinions of this and other

courts:

9/ Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556 (1974).

4

(a) The "small number" of one-race elementary schools

»

to which the district court alluded (pp. 68a, 73a, infra)

in fact amounts to one-third of the elementary facilities in

Montgomery? these schools enroll almost 6 0% of all black

10/

elementary students. Although the district court sought

to justify this result by pointing to its expectation of full

desegregation at grades 7-12 (p. 77a, infra), actual experience

has been "ff]alse to predictions . . . more than a quarter of

the black junior high school students in the City are locked

in schools 85% or more black, and nearly 40% in schools 80%

11/or more black.“

(b) The district court's statement, that residential

patterns unrelated to the historic dual system in Montgomery

are the sole cause of present-day segregated enrollments, also

ignores important facts. Seven of the ten elementary schools

to which the court refers (see p. 68a infra) were all-black

12/

schools under the dual system. The school board's plan

10/ As the dissent points out, under the district court's plan

ten Montgomery elementary schools are over 90% black, and another

is 86% black (see p. 11a infra).

11/ See Judge Goldberg's dissenting opinion at p. 47a infra.

12/ See the dissenting opinion at p. 22a n. 17 infra.

5

creates additional black schools by mandatory reassignments

13/

which decrease the level of integration. And the district

court itself previously castigated Montgomery school officials

for construction and other practices which could only have the

14/

effect of cementing in and exacerbating neighborhood segregation.

13/ For example, Bellinger Hill was 73% black in 1973-74, and

is 86% black under the district court-approved plan; Fews, 99%

black in 1973-74, was assigned 200 additional black students and

is an all-black school this year; Loveless, which was 99% black

last year, was assigned all former McIntyre Elementary pupils and

remains 99% black during the current term. (See table attached

to dissenting opinion at pp. 52a-53a infra). Baldwin Jr. High

School was 48% black last year, was projected to be 73% black in

1974-75 and actually opened 85% black (id. at 54a). The transfer

of the white students formerly attending Baldwin to Carver so that

the latter school would be 60% white is consistent with the specific

ratio goals of the board's plan: although system-wide enrollment

is approximately 50% black, only Bellingrath and Lanier, of 49

schools, were projected to enroll between 40% and 80% black students

(id. at 52a-55a). There was far more variation expected under the

plans of the plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenors, which the

district court characterized as being designed to produce "a racial

balance" (see pp. 63a, 66a infra).

14/ Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 289 F. Supp. 647

651-52 (M.D. Ala. 1968):

The evidence further reflects that the defendants

have continued to construct new schools and expand

some existing schools; certainly, there is nothing

wrong with this except that the construction of

the new schools with proposed limited capacities

geared to the estimated white community needs and

located in predominantly white neighborhoods and

the expansion of the existing schools located in

predominantly Negro neighborhoods violates both

the spirit and the letter of the desegregation

plan for the Montgomery County school system.

Examples of this are the construction of the

Jefferson Davis High School, the Peter Crump

[continued on next page]

6

(c) The district court's opinion lacks specific factual

findings concerning the times and distances of pupil trans

portation which would be required under either the plaintiffs'

14/ (Continued)

Elementary School and the Southlawn Elementary

School — all in predominantly white neighbor

hoods — and the expansion of Hayneville Road

School and the Carver High School, both in

predominantly Negro neighborhoods. The location

of these schools and their proposed capacities

cause the effect of this construction and the

expansion to perpetuate the dual school system

based upon race in the Montgomery County School

System.

One of the most aggravating courses of conduct

on the part of the defendants and their agents

and employees related to the new Jefferson Davis

High School to be located in the City of Montgomery

and operated commencing with the school year 1968-

69. The defendants in locating this school placed

it in a predominantly white section of Montgomery.

The evidence reflects that in determining the

capacity of the school they approximated the number

of white students residing in the general vicinity

and constructed the school accordingly; they have

adopted a school name and a school crest that are

designed to create the impression that it is to be

a predominantly white school; they have hired a

principal, three coaches and a band director,

all of whom are white; they have actively engaged

in a fund-raising campaign for athletic and band

programs only through white persons in the

community; they have contacted only predominantly

white schools for the scheduling of athletic events

and they have made tentative arrangements to join

the Alabama High School Athletic Association —

the white association. . . .

[continued on next page]

7

or plaintiff-intervenors' plans in order to completely desegre

gate the Montgomery County system. Certainly there is no

predicate for a conclusion that the necessary busing would

"either risk the health of the children or significantly

impinge on the educational process," Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen-

" 15/

burg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 30-31 (1971). Judge Goldberg

14/ (Continued)

All of this means that the defendants have

failed to discharge the affirmative duty the

law places upon them to eliminate the operation

of a dual school system. . . .

The manner in which the defendants have constructed

new schools, the location and proposed capacity

of these schools, and the manner in which the

defendants have expanded Negro schools and the

location of these Negro schools make it clear

that the effect of these new constructions and

the effect of the expansions have been designed

to perpetuate, and have the effect of perpetuating,

the dual school system in the Montgomery County

schools. . . .

Cf. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1,

at 20-21 (1971).

15/ What is clear is that the school board's plan requires far

greater transportation of black than white students; although

many black students are reassigned and transported to formerly

white schools — some now virtually all-black (see note 13 supra)

the Superintendent frankly admitted that no white students were

assigned to formerly black elementary schools unless they lived

within walking distance of them (April 24, 1974 transcript at pp.

237, 240).

8

noted in his dissent, for example, that "apparently the

length of the trips — of additional elementary student busing

envisioned in connection with the plaintiffs-intervenors1 plan

very closely parallels the increase in elementary school busing

under the desegregation plan implemented in Swann . . . " (pp.

38a-39a infra). This is hardly surprising, given the relatively

small geographic area (urban Montgomery) which is at issue

16/

here.

Finally, the district court's reliance on the expected

lack of stability of any further desegregation, because of

anticipated white flight, is explicitly contrary to a long line

of this Circuit's school desegregation cases, from before

Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., 409 F.2d 1287, 1289

(5th Cir. 1969) to and beyond Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ.,

465 F .2d 369 (5th Cir. 1972). All of the members of this Court

have joined in such rulings, which until this decision were

thought to be required by controlling Supreme Court precedent.

These are but examples of the contradiction between the

record and the district court's opinion adopted by the panel

majority in this case; and of the serious conflicts between the

16/ Pupil transportation is an issue only with respect to the

schools inside the Montgomery city limits. Students living in

the suburban "peripheral area" are already transported under the

plan (see the dissenting opinion, at p. 6a, text at n. 4, and

p. 7a, infra).

panel's decision and most other school desegregation rulings

of this Court. The April 11 ruling herein appears on its

17/

face to be a clear departure from prevailing law. Because

it is a school desegregation case, there was no opportunity to

18/

present oral argument. Despite a lengthy and scholarly

dissent, the Court's three-sentence per curiam Order merely

refers to a district court opinion which, as noted by- appellants

and by Judge Goldberg, fails to make critical fact findings in

support of its judgment. If this result is to be capable of

explication or analysis, there must be either a reasoned decision

from this Court or far more detailed findings by the district

court.

It is essential — to the black schoolchildren of

19/

Montgomery for whom Brown v. Board of Education has as yet

had little or no meaning, to the maintenance of respect for

this Court among both members of the Bar and of the general

17/ In addition to the serious questions raised in this case

about the application of Fourteenth Amendment requirements for

nondiscriminatory assignment of pupils, the panel's affirmance

approves sub silentio the truly unprecedented action of the dis

trict court taxing the costs of this school desegregation case

against plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenors. This error alone

warrants reconsideration eri banc.

18/ Shortly before the decision was rendered, appellants filed a

formal Suggestion that oral argument might be appropriate. However,

despite the fact that the ruling was not unanimous, no opportunity

for argument was allowed. Compare Outline of Procedures, 63 F.R.D.

347, 356 (1974); Circuit Realignment; Hearings before the Sub

committee on Improvements in Judicial Machinery of the Committee on

the Judiciary, U.S. Senate, 92d Cong., 2d Sess., at 86 (testimony of

Chief Judge Brown, Sept. 24, 1974). Rehearing should be granted to afford this opportunity.

19/ 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

- 1 0 -

public, and to the preservation of the Constitution — that the

full Court review and reverse the decision of the panel majority

in this action.

HOWARD A. MANDELL

212 Washington Building

P. 0. Box 1904

Montgomery, /Alabama 36103

Respectfully submitted,

FRED T. GRAY

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104-

Attorney for Intervenors- JACK GREENBERG

Appellants JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

11

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 22nd day of April, 1975,

I served two copies of the foregoing Petition for Rehearing

with Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc upon counsel for the

parties and amicus curiae herein, by depositing the same in

the United States mail, first class postage prepaid, addressed

as follows:

Vaughan Hill Robison, Esq.

Joseph Phelps, Esq.

815-30 Bell Building

P. O. Box 612

Montgomery, Alabama 36102

Brian K. Landsberg, Esq.

Joseph D. Rich, Esq.

William C. Graves, Esq.

Richard Johnston, Esq.

Civil Rights Division

U.S. Department of Justice-

Washington, D.C. 20530

-12-

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

APP): TDS * .

U. S. COURT o r A."

F I L E D

No. 74-2633

APR 1 1 W 5

■---------------------- — \y. WADSWORTH

C'i ]'rirARLAM CARR, JR., a minor by ARLAM CARR &

JOHNNIE CARR, ETC., NT AD.,

Plaintiffs-Appc11an ts,

NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, INC.,

Interverior,

PENELOPE ANNE JENKINS, ET AD.,

Int crvenors-AppelInnt s,

versus

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

ET AD., ETC.,

Defcndants-Appellees,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Amicus Curiae.

Appeals ora the United States District Court for the

_____________ '■_ Micelle District of .Alabama

( April 11 , 1975)

Before GENIN, GOLDBERG and DYER, Circuit Judges.

r

PER CURIAM:

Wc affirm the judgment of the district court for the reasons

set forth in its opinion, 377 F . Supp. 1123 (M.D. Ala. 1974). The

judgment of the district oourt is attached as Appendix A. Tie take

note of the history of this litigation as reflected by the opinions

of the district court, this court, and the Supreme Court cited in

the district court's opinion. The Montgomery County school system

has been under the scrutiny and surveillance of the federal judiciary

for a substantial period' of time and such scrutiny and surveillance

will continue. . '

AFFIRMED.

©

.• -1

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE

DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION

ARLAM Q\RR, J R . , ET A t . ))

Plaintiffs, )

)

NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, )

INC.; PENELOPE ANNE JENKINS; .• )

ET AL., )

)

Plaintiff-Intervcnors, )

)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ))

Amicus Curiae, ))

v. ))

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BOARD )

OF EDUCATION, ET AL., )

Defendants. )

F I L E D

MAY 2 A

HANF. P. GORDON, C lc R‘f

BY______ ______________

DEPUTY ClERE

CIVIL ACTION NO. 2072-N

JUDGMENT

Pursuant to the findings of fact and onclusions of law made and

entered.in a memorandum opinion filed in this cause this date, it is the

ORDER, JUDGMENT and DECREE of this Court that:

1. The plans presented by the plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervcnors

for the further desegregation of the Montgomery County school system be and

J

arc hereby rejected.

2. The plan presented by the defendant Montgomery County Board of

Education on January 15, 1974, revised on March 29, 1974, and modified on

May 8, 1974, be and is hereby approved and ordered implemented.

3. The school board's plan will be implemented forthwith, with the

student assignments to the various schools within the system to be effective

with the commencement of the 1974-75 school year.

4. The school board will file with this Court on September 15, 1974,

and on February 15, 1975, and on said dates each year thereafter, written

reports reflecting the actual student and teacher assignments, by race, in

each school ir. the system.

5. The costs incurred in this proceeding be and they arc hereby

taxed one-half against the plaintiffs and one-half against the plaintiff-

intervcnors.

/Vj9

Done, this the *3- day of May, 1974.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUduE

No. 74-2033 - Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Education

GObDBERG, Circuit Judge (dissenting):

Respectfully, but without equivocation, I dissent.

This suit was brought in 1904 to desegregate the public

schools in Montgomery County, Alabama. Its progress has been

recorded at several stages in opinions by the able District Judge,

±y

by this Court, and by the Supreme Court. In August, 1973,

/ Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., M.D. Ala.,

1964, 232 F.Supp. 705; further relief ordered, 1966,

253 F.Supp. 306; further relief ordered, 1968, 289

F.Supp. 647, ziff1 d, 5 Cir. 400 F.2d 1, af f' d, 1969,

395 U.S. 225, L.Ed.2d , S.Ct.;

further relief ordered by district court,

1970, [unreported], aff'd with modifications, 5 Cir.

1970, 429 F.2d 302.

J

/ i, ■'

the district court ordered the parties then in this case — the

the

plaintiffs,/defendant School Board, and the United States — to

submit proposals for further desegregation of the Montgomery

County system in light of decisions by this Court and the Supreme

the in 1970

Court since/entry/of the last comprehensive order in the case.

One week later, plaintiffs-intervenors, Jenkins,

et al., filed their motion to intervene, which was granted in

February, 1974. During the first four months of 1974, plaintiffs,

plaintiffs-intervenors, and the School Board each prepared and

proposed new pupil assignment plans. Hearings were held on

_ 1 _

each plan in April. The School Board amended its plan in response

to prodding from the Bench, and in an order entered May 22, 1974,

opinion F. Supp. 1123,

and/reportcd at 377 / the district court adopted the School Board

plan, as amended, in its entirety. Costs were taxed half against

the plaintiffs and half against the plaintiffs-intervenors.

The plaintiffs, the plaintiffs-intervenors, and the United

States appeal, arguing between them that the district court erred

in adopting the School Board's plan for the assignment of elementary

and junior high school students, that the School Board assignment

plan saddles black elementary school students with a disproportion

ate transportation burden, and that costs should have been taxed

against the School Board,

would

I /hold that the district court should not have adopted

the School Board's proposed assignment plan for the elementary

grades because it fell short of establishing a unitary school

system, and there was no sufficient finding that no workable alter

native could be implemented. The record indicates

additionally that the School Board plan for the assignment of

junior high students,as implemented, fails to comply with consti-

would

tutional mandates. Accordingly, 1/ remand to the district court

4

for further proceedings to develop workable

unitary school assignment plans for the elementary and junior

high grades. In light of this I would find it unnecessary

at this time to pass on the appellants' claims of unequal trans-

would

portation burdens. i /vacate the district court's award of costs

in favor of the School Board, to permit the entry of an appropri

ate award after the further proceedings on remand.

y

I

Background

For the 1973-74 term, Montgomery County public schools

enrolled 36,016 students, 17,042 (47/) of whom were black, and

18,974 (53/) white, in some 54 regular schools, organised along a

1-6, 7-9,- 10-12 pattern. The 36 elementary schools enrolled/ , '

18,449 students (9,279, or 50/, black), the 13 junior high schools

9,644 (4,390, or 45/, black), and the 5 high schools 7,923

JJ(3,373, or 43/, black). All but 7 of the schools then in use

stood within the corporate limits of the City of Montgomery, and

the total county population is similarly concentrated within the

City.

LV We rely here upon the figures referenced in the

district court's opinion, although the plaintiffs-

• intervenors assign some minor inaccuracies thereto.

The student population residing in the area of Montgomery

County outside the City is predominantly black. Within the City

the student population is predominantly white: the eastern half

of the City is more conveneratodly white: most of the western

half is virtually all-black: and a narrow integrated corridor

running Perth-South bisects the City. Under the desegregation

plan adopted in ,970 and effective in 1979-74, most pupils within

the City were as:

school children in

assigned to neighborhood schools.- Outside the City,

JL7

all but the extreme south of die county were

organized into "periphery zones.'

-'1-/ These students attended Dunbar Elementary School

(l-f>), and Montgomery County High School (7-12),

botl( of which remain virtually all-black under all

plans proposed to the district couxt.

Most of these "periphery zone2" students were bused to schools in

the Cityi.ty, and they made up the majority of the 11,175 student-

jy

(31%) bused by the county.

j u During the 1973-74 terra, some 5,308 elementary school

students, 3,759 junior high students, and 2,029 senior

high students were bused.

Implementation of the neighborhood—assignment based plan

adopted in 1970 left a high number of all-one-race or virtually

all-one-race schools. The record discloses that in the Spring

%

of 1974/ 15 elementary schools were 87% or more black, and 6 were

87% or more white; 6 junior highs were 94% or more black, another

was 85% black, and 1 was 90% white; 1 senior high was 99% black

and another was 86% black. Responding to these conditions, in

J

its order/below the district court replaced its 1970 plan with

the School Board's most current proposal. That plan adheres to

f

the techniques employed in the 1970 plan, and, unlike the plans

suggested by the plaintiffs and plaintiffs-intervenors, eschews

pairing or clustering of schools.

At the high school level, the School Board plan employs

rezoning and peripheral reassignments to reduce the percentages

of black students at each City school to 33-40%; only Montgomery

County High School, in the extreme south of the County, retains

5_y

an 07% black student body. None of the

See Appendix C; see also note 35 infra.

appellants question the propriety of this high school plan, and

appeal was

it requires no further discussion. Rather, this / brought tc

test the constitutional sufficiency of the School Board's student

assignment plans for the elementary and junior high levels. I

will discuss each of the two educational stages in turn.

II

Elementary School Plan

The plaintiffs and plaintiffs-intervenors each proposed

alternative plans for assignment of elementary school students.

Each plan aimed at eliminating "racially identifiable" schools,

J

7 . :• •

defined at the outset by each plan's architect as a school whose

racial balance varied more than 10-15% from the racial make-up

of the county-wide student body for that level. Neither plan

clung strictly to such statistical profiles, however, and each

left at least one virtually all—black elementary school.

The plaintiffs' plan was directed only toward the elemen

tary schools within the City. It generally retained the zone line

drawn by the School Board, but changed assignment patterns within

those zones through pairing and clustering, and some modification

of peripheral

- G -

assignments, to reach a 24-66% black concentration in each city

school. The district court calculated that implementation of the

plaintiffs' plan would require reassignment of 43% of the elemen

tary school population and additional transportation of 20% of

the elementary student body. The district court concluded that

the plaintiffs' plan v.>as designed "for the sole purpose of attain-

, 377 F. Supp. at 1129,

ing a strict racial balance in each elementary school involved,"

and that the increased busing, large scale reassignment of studen

and teachers, and the "fracturization of grade structure" in-

"be disruptive to the educational.processes

herent in pairing and clustering,/would place an excessive and

unnecessarily heavy administrative burden on the school system."

i \

•' M*

The plaintiffs-intervenors proposed a more complicated ove:

haul of elementary school assignments. Their plans abandoned the

School Board zone lines, replacing them with two sets of new

zones: one set of strip zones, running generally North-South, for

grades 1-3; another set of strip zones, running generally East-We

for grades 4-6. -Utilizing this basic network, the plaintiffs-

intervenors offered two possible plans. The simpler plan merely

assigned students to the school within their proposed contiguous

zone. This loft 400 black students in grades 4-G in a school

01% black, and 2233 of the black primary grade 1-3

children in schools 04% or more black. The plaintiffs- ]

intervenors' alternative, and preferred, plan retained their grade

zone and the single 81% black school-

4-G/pattern/ but added satellite zoning to the primary grade

v the total of

assignments, reducing to 402/black students in one 84% black

primary school. The plaintiffs-intervenors' plan offered trans

portation advantages over the plaintiffs1 plan, requiring addi

tional busing for only 11% of the elementary school students,

according to the district court. There was evidence that the7 •

plaintiffs-intervenors1 plan would prove the more likely thwarted

in practice, however, and the district court found that implements

tion of either of the plaintiffs-intervenors1 plans would in

volve reassignment of 60—70% of all of the elementary school

population. The district court entered no specific findings as

to the workability of the plaintiffs-intervenors1 plans.

The School Board plan adopted by the district court for

the assignment of elementary school children furthers desegrega

tion by closing 5 previously virtually all-black elementary

schools and assigning some pupils from those schools to predom

inantly white schools, and by reassigning some 400 black students

at another virtually all-black school to 4 predominantly white

schools. Under this plan, however, 55% of the black students

v/ere projected to be enrolled at elementary schools 87% or more

black, and 44% were expected to attend elementary schools 93%

or more black. The statistics showing actual enrollment as of

September 15, 1974, demonstrate that the true profiles are slightly

6 /

worse. Under the School Board plan no white elementary school

See 7\ppendix A & note 37 infra.

!

students were reassigned to a school that would remain predomin

antly black. The School Board estimated that its elementary

school plan would produce a significant net reduction of trans

portation .

- 9

A

Unitary School System

As the Supreme Court established in Green v. School Bd.

of New Kent County, I960, 391 U.S. 430, 436, 20 L.Ed.2d 716,

722, B8 S.Ct. 1689, ____ , "The transition to a unitary, non-

racial system of public education . . . is the ultimate end

to be brought about" in school desegregation cases. In this

pursuit the school authorities and district court "will . . .

necessarily be concerned with the elimination of one-racc

schools." Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 1971,

J

402 U.S./l, 26, 28 E.Ed.2d 554, 572, 91 S. C-t. 1267,_______ .

The district court, relying on Ellis v. Board of Public Instruc.

of Orange County, 5 Cir. 1970, 423 F.2d 203 (Ellis I), concluded,

however, that the persistence of virtually all-black elementary

schools in Montgomery County under the School Board's "neighbor

hood assignment" plan did not prevent that system from reaching

the unitary status mandated by Green. I disagree.

10

jV

Ellis I approved, as modified, a student desegregation

which was

plan for Orange County, Florida,./based on neighborhood school

assignments and left several virtually all-black schools. We

held that "[u]nder the facts of this case, it happens that the

school board's choice of a neighborhood assignment system is

adequate to .convert the Orange County school system from a dual

to ci unitary system." 423 F.2d at 208, n. 7. Ellis 1 did not,

"neighborhood school"

• however, automatically sanctify any/student assignment plan which

placed the same percentages of students in fully integrated

schools. Rather, as we explicitly cautioned,

There arc many variables in the student assignment

7 :

approach necessary to bring about unitary school

zv

The district court's opinion below, 377 F.Supp at 1137 n.36as

erroneously reads the Ellis I opinion /approving the degree

of desegregation under the Orange County plan without modification

- 11

systems. The answer in each case turns, in the

final analysis, as here, on all of the facts in

cluding those which are peculiar to the particular

system.

423 F .2d at 208, n. 7. This passage has become a refrain in our

iL/

school desegregation decisions. Indeed, our school desegre

gation cases are too numerous, their facts, figures, and conditions]

too particular, and our remedies too flexibly fashioned, to lend

themselves to a simple sorting into neat rows. But I believe that

the weight of our pre-Swann decisions adopting and adapting the

neighborhood assignment approach of Ellis I do not permit us t(

the

certify the School Board's plan for Montgomery as/achievement

I V

of a unitary system.

± 7 ~ 7 ~ 7See, e■g., Henry v. Clarksdale Mun. Sep. Sch. Dist., 5 Cir.

1970, 433 F.2d 387, 390; Andrews v. City of Monroe, 5 Cir. 1970,

425 F .2d 1017, 1019.

U Seefe ■g., Ross v. Eckels, 5 Cir. 1970, 434 F.2d 1140, cert

denied, 1971, 402 U.S. 953, 29 L. Ed. 2d 123, 91 S. Ct. 1614;

Valley v. Rapides, 5 Cir. 1970, 434 F.2d 144; Conley v. Lake

Charles School Bd., 5 Cir. 1970, 434 F.2d 35; Allen v. Board of

Public Instruc . of Broward County, 5 Cir. 1970, 432 F.2d 362,

cert, denied, 1971 402 U.S. 952, 29 L.Ed.2d 123, 91 S. Ct. 1609,

1612; Pate v. Dade County School Bd. 5 Cir. 1970, 434 F.2d. 1151,

cert, denied, 1971, 402 U.S. 953, 29 L.Ed.2d 123, 91 S. Ct. 1614;

Bradley v. Board of Public Instruc. of Pinellas County, 5 Cir.

1970, 431 F.2d 1377, cert, denied, 1971, 402 U.S. 943, 29 L.Ed.2d

111, 91 S. Ct. 1600; Hightower v. Went, 5 Cir. 1970, 430 F.2

- 12 -

fn continued

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruc. of Hillsborough County,

"neighborhood assi'gnment"

5 Cir. 3970, 427 F.2d 074. In each of thcse/cases we required'

concentration

that the / of black students attending virtually ali

bi ack schools be reduced far below the level accomplished under

the School Board plan for Montgomery. This is not, of course, to

disregard the complex of other variables present in each case.

See also, Wright v. Board of Public Instruc. of Alachua County,

5 Cir. 1970, 431 F.2d 1200.

As we concluded in Allen v. Board of Public Instruc.of Broward

/

County,5 Cir. 1970, 432 F.2d 3G2, "In the conversion from dual

school systems based on race to unitary school systems, the con

tinued existence of all—black or virtually all.—black scliool.s is

n ££/

unacceptable where reasonal^l.e alternatives exist."

J, f •7 ■'

1 0/

Quoted with approval in Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of

Educ., 5 Cir. 1972, 457 F.2d 1051, 1095.

Even were the Sdiool Board's plan adequate to achieve a

unitary school system under Ellis I and the cases immediately fol

lowing it, liowever, I thinly it manifest that the School Board's

plan cannot stand after Swann; Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs

of Mobile County, 1971, 402 U.S.

33, 20 b. Ed. 577, 91 S.Ct. 12B9; and Keyes v. School District

Ho X, 1 9 7 3 , 413 U.S. 189, 37 b.Ed.2d 548, 93 S.Ct. 2606. Swann

shed new light on the constitutional requisites in school desegre

gation cases, and since Swann we have refused to accept mere com

pliance with our decision in Ellis I as the mark of a school board

plan's constitutional sufficiency. Indeed, we held in Ellis v. Bojr

cerjt. _d er> i e <c

of Public Instruc. of Orange County, 5 Cir. 1972, 465 F.2d 870, /

1973, 410 U.S. 966, 35 b. Ed. 2d 700, 93 S. Ct. 1438 (Ellis IT),

that the school board was obliged to desegregate each all-black

11 /

school remaining in Orange County under our prior holding.

See also Dandridge v. Jefferson Parish School Bd., 5 Cir. 19/2,

j-iy456 F.2d 552, 554, cert, denied, 1972, 409 U.S. 978, 34 L.Ed.

2d 240, 9''3 S. Ct. 306.

11/ We found the Orange County system could be unitary, how

ever, although two elementary schools, to which 7% of the system's

black elementary students were assigned, continued with 79% black

enrollments, where 14% of the system's black students had employed

the majority to minority transfer program

I2y

Compare bee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ. (Anniston), 5 Cir

1973, 483 F .2d 244 (post-Swann), with bee v.Macon County Bd. of

Educ. (Anniston), 5 Cir. 1970, 429 F.2d 1218 (pre-Swann). Rut cf-

bee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ. (Troy), • 5 Cir. 1973, 47o

F.2d. 748 (apparently denying interim relief only).

- 34

TJ,e concentration of black students in virtually all-black

schools conti:endicts the assertion that the School Board's plan

these

for Montgomery establishes a unitary school system under/control

ling standards. Compare, c j , ; Swann,

»

KlliB xi, supra; Flax v. Potts, 5 Cir. 1972, 464 F.2d 869, 869,

cert, denied, 1972, 409 U.S. 1007, 34 L. Ed.2d 299, 93 S.Ct. 433

(middle schools, high schools); Dandridge v..Jefferson Parish Scho

Bd., 5 Cir. 1972, 456 F.2d 553, cert, denied, 1972, 409 U.S. 978,

34 L. Ed. 2d 240, 93 S. Ct. 306; cases cited, note 9 supra;

see also Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 1973, 413 U.S. 189, 199 n.

X,. Ed. 540, 558, 93 S. Ct. 2606, -------• The teaching of10, 37

school which reflects vestigial discrimSwann and Keyes is that no

J

if

ination through its virtually single-race student body can be

omitted from a desegregation plan unless inclusion is unworkable,

where desegregation is possible wo can tolerate no abandonment

of some given portion of students locked into a uniracial educa

tional experience.

in appraising a school board’s plan we are, of course,

attentive to conditions other than racial concentrations. I can

not agree, however, with the suggestion that compliance with the

remaining five of the six requirements established m Green v.

15

School Bonrd ot Now Kent Comity, 19W, 391 «0, 435, 30 L,

M . 2d. 710, 722, 00 0. Ct. 1009--------, - "£oc»lty, »t»££.

icialar activities and facilities - cantransportation, extra curr

13 / conclude

immunize the School Board’s plan. So to/ would ignore tha

"[i]n Green the court spoke in terms of the whole system, " F,1 lis

WOUld

1, 423 F.2d at 204, and/disregard the recognition that student

assignment is the single most important single aspect of a de

segregated school system. Our cases have always required complr-

14/

ance with all six particulars.

13/ 377 F.Supp. at 3.138.

p/e / I assume arguendo that the Board plan complies with the

remaining five benchmarks enumerated in Greeip.

14 /

Sc6, c. o;., Ellis II, supra; Valley v. Rapides, 5 Cir. 1970,

434 F .2d. 144; Allen v. Board of Public Instruc. of Broward

County, 5 Cir. 1970, 432 F .2d 362, cert, denied, 1971, 402 U.S.

962, 29 L. Ed.2d 123, 91 S. Ct. 1609, 1612; Pate v. Dade County

School Bd., 5 Cir. 1970, 434 F.2d .1151, cert, denied, 1971,

402 U.S. 953, 29 L.Ed.2d 123, 91 S. Ct. 1614; Henry v. Cl arksdale

Hun. Sep. School Dist., 5 Cir. 1970, 433 F.2d 387; Bradley v.

Board of Public Instruc. of Pinellas County, 5 Cir. 1970, 433

F.2d 387; Bradley v. Board of Public Instruc. of Pinellas County,

5 Cir. 1970, 431 F.2d 1970, cert, denied, 1971, 402 U.S. 943,

29 L. Ed. 2d 111, 91 S. Ct. 1600; City of Monroe v. Andrews, 5

Cir. 1970, 425 F.2d 1017. See generally Singleton v. Jackson

Mun. Sep. School Dist., 5 Cir.(cn banc) 1970, 419 F.2d 1211.

16 -

J

'J’he School Board additionally argues' that the secondary schools

;n Montgomery County are desegregated, and points out that wc have

taken note of thorough integration at the secondary level, in

some cases approving assignment plans which left some all-black

primar■y schools. Jlee Lee v. City of Troy Bd. of Educ., 5 Cir. 1970

432 F.2d 819, 822; Hightower v. West, 5 Cir. 1970, 430 F.2d 552,

• also

555. This argument/fails here. Even assuming arguendo that the

secondary schools in Montgomery County were fully integrated, we

would, as in the

>-Swann /cases relied upon by the School Board,attach little

/ • ‘pre

weight to that consideration'. Moreover, as it has become quite

clear," [Tlhis court has, with limited exceptions [not applicable

here] disapproved of school board plans which exclude a certain

age grouping from school desegregation." Arvizu v. Waco Indep.

School Dist., 5 Cir. 1974, 495. F.2d 499, 503. In the.light of

Swann and our developed case law, it is manifest that the pro-

grL-essive integration of Montgomery''s high schools is no excuse for

17

at 16/

the continued failure to desegregate/the elementary level.

In some cases it may prove necessary to avoid trans

portation of school children of very tender age, sec

generally Swann, 402 U.S. at 31, 20 Jj.bd.2d at ->7->

91 S. Ct. at ____; Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Indep.

School Dist., 5 Cir. (en banc) 1972, 467 F.2d 142, 153,

cert, denied, 1973, 413 U.S. 922, 37 L. Ed. 2d. 1044,

93 S. Ct. 3052. But such exceptions are carefully

limited, see, c .g ., Flax v. Potts, 5 Cir., 1972, 464

F.2d 865, 869, cert, denied, 1972, 409 U.S. 1007, 34

I,. Ed.2d 299, 93 S. Ct. 433; Lockett v. Board of Educ.

of Muscogee County School Dist., 5 Cii~. 197]., 447 F.2d

472, 473; cf. Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 5 Cir.

1973, 475 F .2d 749 (apparently denying interim relief

only).

/

, /

/ \ :

In cases where racially identifiable primary schools

cannot feasibly be eradicated, of course, a district

court should endeavor particularly to insure that

students from such schools will graduate to fully

integrated schools.

in sum, a neighborhood school assignment plan may be ade

quate if it establishes a unitary school system; but such assign

merit is not "per se'adequate." Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs

of Mobile County, 1971, 402 U.S. at 37, 20 L.Ed.2d at ~>01, 91

S. Ct. at A review of the circumstances of

the Montgomery County system, particularly the concentration

of black elementary students in virtually all-black schools,

reveals that the School Board plan approved by the district

court was insufficient to achieve a unitary school system as

required under Green and Swann. Such a plan can stand only

if its lack 6f unitary status is not attributable to state

action, or if no further remedy is workable

n

Residential Patterns

The district court declined to require further desegre

gation of the remaining virtually all-black elementary schools

in part

in Montgomery County,/because it considered the persistence of

those schools to be "a result of residential patterns and not of

the school board's action — either' past or present." 377 p.

Supp. at. 1133. Because the district court's opinion offer

no supporting discussion, it is unclear whether the district

court believed that the present existence of virtually all-black

in part

schools could be laid/to residential patterns established dur-

J

, /

i . ■

ing the period of statutory school segregation yet not induced

by that sterte action, or that the development of racially iden-

tifitible neighborhoods since the onset of efforts to integrate

17 /

the schools had precipitated the virtually all-black schools.

l u ~ :

The record discloses that of the 11 elementary

schools which retain a projected black population

over 80% under the School Board's “neighborhood

assignment" plan, 8 (all but Bellinger Hill,

Davis, and Pintlala) had been black schools be

fore 1970.

In either event, I think the district court erred in its

20

determination.

Aware that "[p)eople gravitate toward- school facilitie

just as schools are located in response to the needs of peopl

the Supreme Court has recognized that

- 21

ft)he location of schools may . . . influence

the patterns of residential development of a metro

politan area and have important impact on composi

tion of inner-city neighborhoods.

In tile pact, choices in this respect

have been used as a potent weapon for creating

or maintaining a state-segregated school system.

2 0,

Swann,402 U.S. at/21, 28 L. Ed. 2d at 569, 91 S. Ct. at .

Moreover,

[Ajeormection between past segregative acts,and

present segregation may be present even when not

apparent and . . . close examination is required

before concluding that the connection does not

exist. Intentional school segregation in the past

J/ j

may,have been a factor in creating a natural environ

ment for the growth of further segregzition.

Keyes , 413 U.S. 189, 211, 37 L. Ed.

2d 548, 565, 93 S. Ct. 2686, ________ .

Accordingly, the Swann Court held that while

the existence of some small number of one-race,

or virtually one-race, schools within a district is

not in and of itself the mark of a system that

practices segregation by law [,] . . . in a system

with a history of segregation the need for remedial

- -22 -

criteria of sufficient specificity to assure a

school authority's compliance with its constitu

tional duty warrants a presumption against schools

that are substantially disproportionate in their

racial composition. Where the school authority's

proposed plan for conversion from a dual to a uni

tary system contemplates the continued existence

of some schools that are all or predominately of one

race, they have the burden of showing that such

assignments are genuinely nondiscriminatory. Hie

court- should scrutinize such schools, and the bur-

den upon the school authorities will be to satisfy

the court that their racial composition is not the

result of present or past discriminatory action on

their part.

Swann, 40?. U.S. at 26, 28 L. Ed. 2d 572, SI S. Ct. at

j

, I/ • ■The School Board may satisfy its burden "only- by showing that its

past segregative acts did not create or contribute to the cur

rent segregated condition of the . . . [particular] schools."

Keyes, 413 U.S. at 211, 37 L.Ed.2d at 565, 93 S.Ct. at _____ .

There is no evidence to support a conclusion that the exis-

ence of virtually all-black neighborhood elementary schools, so

derive

far as they / from residential patterns etched before school

desegregation, is innocent of past discriminatory action by the

School Board.

The opinion below lacks the detailed factual findings by

the district court which should reflect the "close scrutiny

required under Swann and Keyes, and the record bears no evidence tc

support the conclusion that the link between past and present

segregation has been severed. While there is much evi

dence of the residential separations between whites and blacks

4

in Montgomery, which in some cases shows that those patterns

are not new, evidence of this sort is insufficient to overcome

the presumption established in Swann connecting the development

of persistently segregated residential patterns with state-mandate

school segregation. See also Dandridge v. Jefferson Parish School

Bd., 5 Cir. 1972, 456 F.2d 552, cert, denied, 1972 409 U.S. 978,

34 L. Ed. 2d 24 0, 93 S. Ct. -306.

■These'principles establish equally well that racial segre

gation in the Montgomery County elementary schools cannot be ex

cused on the ground that segregated residential patterns of some

neighborhoods from which the one-race neighborhood schools draw

have crystallized an the result of population shifts by private

J, f

residents since the court1s initiation of school desegregation.

Such an argument has previously been rejected by this Court.

„ ; “ ’

See Flax v. Potts, 5 Cir. 1972, 464 I'.2d 865, 868,

cert, denied, 1972, 409 U.S.1007, 34 L.Ed.2d 299, 93

S. Ct. 433; cjf. Boyd v. Point Coupee Parish School Bd. ,

5 Cir. 1974, 505 F.2d 632; Hereford v. Huntsville Bd.

of Educ. , 5 Cir. 1974, 604 F.2d 857; Adams v. Rankin,

5 Cir. 1973, 485 F.2d 324.

To be cure, the Supreme Court has made clear that after a school

system attains unitary status,

the communities served by such [a system may not]

remain demographically stable [;] . . . in a grow

ing, mobile society, few will do so. Neither

school authorities nor district courts are con

stitutionally required to mate year-by-year adjust

ments of tlie racial composition of student bodies

' once the affirmative duty to_desegregate has been

accomplished and racial discrimination through of

ficial action is eliminated from the system.

Swann, 402 U.S. at 31-32; 20 L. Ed. 2d. at 575, 91 S. Ct. at ____

But in Montgomery a unitary system has never been achieved, for

"[t]he vestiges of state-imposed segregation [have not] been

eliminated from the assignment of elementary school students,"

Flax v. Potts, 5 Cir. 1972, 464 F.2d 865,868, cert, denied, 1972,

409 U.S. 1007, 34 L.Ed.2d 299, 93 S. Ct. 433, as required under

l*/ .

Swann. ' / •

1U ~

Cf. Ellis v. Board of I’ublic Instruc. of Orange

County, 5 Cir. 1972, 465 F.2d 870, 879-80, cert,

denied, 1973, 410 U.S.966, 35 L.Ed.2d 700, 93 S.

Ct. 1438 (Ellis XI); Dandridge v. Jefferson Parish

School Bd., 5 Cir. 1972, 456 F.2d 552, 554,cert,

denied, 1972, 409 U.S.970, 34 I,.Ed.2d 240, 93 S.

Ct. 306. Moreover, there is even some indication

of Montgomery County School Board action since the

onset of court-ordered desegregation which may tend

to perpetuate the dual system. As the district

court found at i\ prior stage in this litigation, the

location find extent of construction and expansion

of elementary and secondary schools in Montgomery

County have "been designed to perpetuate, and have

the effect of perpetuating, the dual school system."

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., M.D. Ala.

I960, 289 F. Supp. 647, 692. See generally,Swann,

at

402 U.S. at 18-21, 28 L.Ed.2d/568-70, 91 S. Ct.

_____ ; cf. Keyes, 413 .U.S. at 201-05, 37 L.Ed. 2d at

559-61, 93 S. Ct. at .

26a

0

c

Remedy

Because the School Board's proposed elementary school plan

falls short of achieving a unitary system, and this failing cannot

be attributed solely to private action, the district

court should have ordered an appropriate alternative plaan. At

we have said before Swann and reiterated after, ''[i]n the con -

version from dual school,systems based on race to unitary school

systems, the continued existence of all-black or virtually all

black schools is unacceptable where reasonable remedies exist. 2o_y

2 0 /

Allen v. Board of Educ. of Broward County, 5 cir. 1970,

432 F. 2d 362, 367, cert, denied, 1971, 402 U.S. 952, 29 L. Ed.

2o 123, 91 S .. Ct. 1609, 1612, quoted in Boykins v. Fairfield

Bd. of Educ., 5 Cir. 1972, 457 F.2d 1091, 1095.

The district court discarded the plans proposed by the

plaintiffs and plaintiffs-intcrvenors, after determining that

they aimed at balancing black/white student populations on

tibstract ratios, rather than simply creating a unitary acsignment

plan. Although the plaintiffs and plaintiffs-intervenors protest

) 0 ck

27 -

thiit .their use of reitios as indicators of residual-

ly discriminatory school assignments remained within the bounds

approved by the Supreme Court in Swann, 402 U.S. at 22-25, 28

l,.Ed.2d at 570-72, 91 S.Ct. at ____, 1 would not hold that the

district court abused its discretion in choosing not to follow

those plans. Nevertheless, the elimination of those proposals

did not relieve the district court of its duty to exercise its

"broad power to fashion a remedy that wi11 assure a unitary school

system," and to"makc every effort to achieve the greatest possible-

degree of actual desegregation and . . . [eliminate] one-race

Jj f

schools." Swann, 404 U.S. at 16, 26, 20', L.Ed.2d at 567,' 572, 91

S.Ct. at ___ _. Upon determining that none of the alternatives

presented was satisfactory, the district court should have held

further proceedings to forge a workable and effective plan. See

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Indep. School Dist., 5 Cir. (en banc)

1972, 467 F.2d 142, 152, cert, denied, 1973, 413 U.S. 922, 37

L. Ed.2d 1044, 93 S. Ct. 3052. The district court could suppor.t

its failure so to proceed only by a conclusion that no further

desegregation of the elementary school population was workable

oil any plan.

- 28

I

'Die School Board has consistently maintained that no

workable means exists .for increasing desegregation in the

and

elementary schools,./ the district court agreed, finding "that the

remaining predominantly black schools cannot be effectively de

segregated in "a practical and workable manner" and that the

School Board plan achieved "the greatest possible degree of actual

desegregation, taking into account the 'practicalities of the

situation.'" 377 F. Supp.at 1135. These conclusions are

drawn on insufficient or improper factual considerations, however,

J, /7 • '

and are thus inadequate as a matter of law.

The district court reasoned that any further elementary

school desegregation would require cross-busing of black and white

students which "would not, under the circumstances of this case,

accomplish any realistically stable desegregation." 3^7 F. Supp.

21 / no

at 1132. Die opinion carries/discussion or subsidiary findings t

also

21 / The district court/forecast that the plans of

the plaintiffs and plaintiffs-intervenors would

provide only "an extremely unstable desegregated

system." 377 F. Supp. at 1131.

explain its concern with the stability of desegregation. Ap

parently the district court was persuaded by_ the School Board's

_22/

attempt to demonstrate that busing of white children into black

See, e.g., Transcript, April 24, 1974, at 240.

neighborhoods to attend traditionally black schools would in many

cases be met with withdrawal of white students from those schools.

But it is well- settled that the threat of "white flight," however

likely, cannot validate an otherwise insufficient desegre-

2 3 /

gation remedy. To the extent that it considered white flight

237 See, c .g ., Monroe v. Board of Commissioners or the

City of Jackson, 1968, 391 U.S. 450, 459, 20 L.Ed.2d

./ /

7‘33, 739, 99 S. Ct.1700, ___; Lee v. Macon County Bd.

of Educ. (Marengo), 5 Cir. 1972, 465 F.2d 369; United

States v. Hinds County School Bd., 5 Cir. 1969, 417

p .2d B52, -858, cert, denied, 1970, 396 U.S. 1032, 24

L.Ed.2d 531, 90 S. Ct. 612; Lee v. Macon County Bd.

of Educ. (Pickens), M.D. Ala. (3 judge) 1970, 317 F.

Supp. 95, 98-99. Cf., e.g., Boyd v. Point Coupee

Parish School Bd., 5 Cir. 1974, 505 F.2d 632; Hereford

v. Huntsville Bd. of Educ., 5 Cir. 1974, 504 F.2d 857;

Adams v. Rankin, 5 Cir. 1973, 405 F.2d 324.

as a factor requiring the moderation of desegregation otherwise

to be ordered, the district court was in error.

30 -

The opinion below door, not sufficiently explicate the rc-

(other than stability) that

ing factors/the district court appraised and the reasoning itmarnrng

followed in determining that no further elementary school desegre

gation was feasible beyond that suggested by the School Board.

The district court simply specified the total’s of children to be

be newly bused

reassigned and the number of students to/under the plaintiffs'

and plaintiffs-intervenors1 plans; observed without any specific

findings that busing would involve a substantial increase in the

time and distance that students would have to travel to school; an<

J

then concluded that the plaintiffs1 but not the plaintiffs

interveners’ — plan "would be disruptive to the educational pro

cesses and would place an excessive and unnecessarily heavy admin

istrative burden on the school system." These findings are an

inadequate foundation on which to rest either a determination of

the unworkability of the proposed plans or a conclusion that no

improvement of the Board's solution could be obtained. Nor does_

the face of the record reveal any inherent obstacle to the progres

of all further desegregation in Montgomery through the instrument

of zoning, pairing, and busing. Each of these tools has been

31 -

approved in Swann, 402 U.5. at 27-29, 28 I,.Ed.2d at 573-74, 91 s.

Ct. a t _____and Cisneros v. Corpus Christi, Indep. School Dist.,

5 Cir. (en banc) 1972, 467 F.2 , 342, 152-53,cert, denied, 1973,

413 U.S. 922, 37 L.Ed.2d 1044, 93 S. Ct. 3052, and repeatedly

utilized in this circuit.

24/

We have, where necessary, required both rezoning and pair-

25/

ing or clustering; eind while pairing may not be the remedy of

H 7 _

See_, e.g., Conley v. Lake Charles School Bd., 5 Cir. .1970,

434 F.2d 35, 39-41; Valley v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 5 Cir.

1970, 434 F.2d 144, 147; Pate v. Dade County School Bd., 5 Cir.

3.970, 434 F ..2d 1151, 1158, cert, denied, 1971, 402 U.S. 953, 29

b. 33d. 2d 123, 91 S. Ct. 1614; Bradley v. Board of Public Instruc.

of Pinellas County, 5 Cir. 1970, 431 F.2d. 1377, 1301-03, cert.

denied, 1971, 402.U.S. 943, 29 L. 13d. 2d 111, 91 S. Ct. 1600.

/ •

•See also Wright v. Board of Public Instruc. of Alac3vua County,

5 Cir. 1970, 431 F.2d 1200;

See, e.g., Weaver v. Board of Public Instruc. of Brevard

County, 5 Cir. 1972, 467 F.2d 473, cert, denied, 1973, 410 U.S.

902, 36 L.Ed.2d 177, 93 S. Ct. 1498; Flax v. Potts, 5 Cir. 1972,

464 P .2d 065, 068-69, cert, denied, 1972, 409 U.S. 1007, 34 L. Ed

2d 299, S3 S. Ct. 433; Ross v. Eckels, 5 Cir. 1970, 434 F.2d 1140

1140, cert, denied, 1971, 402 U.S. 953, 29 I,.Ed.2d 123, 91 S. Ct.

1614; Henry v. Clarksdale Mun. Sep. School Dist., 5 Cir. 1970,

433 F.2d 307, 394-95; Allen v. Board of Public Instruc. of Browari

County, 5 Cir. 1970, 432 F.2d 362, 367-71 (citing additional case:

cert, denied, 1971, 402 U.S. 952, 29 L.Ed.2d 123, 91 S. Ct. 1009,

1612. See also Miller v. Board of Educ. of Gadsden, 5 Cir. 1973,

i

fn continued

-102 P.2d 1234; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ., 5 Cir. 1972,

457 F.2d 1091, 1095; Andrews v. City of Monroe, 5 Cir. 1970, 425

F .2 d 1017, 1021.

____

first resort, we have said and repeated that "where all black

or virtually all-black schools remain, under a zoning plan, but it :

prficticablc to desegregate some or all of the black schools by

' 2 7/

using the tool of pairing, the tool must be used." The record,

insofar as it reveals the administrative practicalities associated

4

with rezoning and pairing or clustering, does not appear to pre

clude the imposition of all measures beyond those desired by the

School Board. The record fails to indicate in any way how

Montgomery's situation differs from the conditions existing in

any of the many other school districts in which we have specified

that these measures be employed. Indeed, examination of the

r

record suggests the feasibility of their utilization in several

28/

instances. Accordingly, I would hold that the district court

erred in approving the School Board plan, and remand the cause for

- implementation of a constitutionally sufficient plan.

33

?JL/

Allen v. Board of Public Inntruc. of Broward County, 5 Cir.

1970, 4 32 F. 2d 3G2, 367, cert, denied, 1971, 402 U.S. 952,29 L.Ed.

2d 123, 91 S. Ct. 1609, 1, quoted in Flax v. Potts, 5 Cir. 1972

464 F.2d 865, 868, cert, denied, 1972, 409 U.S. 1007, 34 L.Ed. 2d

299, 93 S. Ct. 433, and Boykins v. Fairfield Board of Educ., 5

Cir. 1972, 457 F. 2d 1091, 1095.

27 /

See Cjsneros v. Corpus Christ! Indep. School Dist. 5 Cir

(en banc) 1972, 467 F.2d 142, 153; cert, denied, 1973, 413 U.S.

922, 37 L.Ed.2d 1044, 93 S. Ct. 305; Conley v . Lake Charles School!

Bd., 5 Cir. 1970, 434 F .2d 35, 39. .

28 /

In regard to the initial administrative difficulties

associated with re-zoning and pairing, we emphasize "[t]he fact

, f

that a temporary, albeit difficult, burden may be placed on the

School Board in the initial administration of the plan . . . does

not justify in these circumstances the continuation of a less than

unitary school system and the resulting denial of an equa] educa

tional opportunity to a certain percentage of the [County]

children." Dandridge v. Jefferson Parish School Bd., E.D. La.

1971, 332 F. Supp. 590, 592,stay denied, 1971 404 U.S. 1219, 30

L. Ed. 2d 23, 24, 92 S. Ct. 18, _____ (Marshall, J., in chambers;

quoting cited language with approval), aff1d,5 Cir. 19 72, 4j6

F.2d 552, cert, denied, 1972, 409 U.S. 978, 34 L.Ed.2d 240, 93

S. Ct. 1306.

TIig district court entered no specific findings rega3-ding

_29/

the extent in time or miles of additional busing required to im

plement any of the desegregation plans before it, nor did it e>:

pre 5S nny conclusions as to whether "the time or distance of travel

[under any possible plan was] so great as to either risk the

health of the children or significantly impinge on the educational

proces

at

" Swann, 402 U.S. at 30-31, 28 L.F,d.2d at 575, 91 S . Ct.

C e r t ainly it is clear that the School Board plan

See Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Indep. School Dist.,

5 rir ] 972 /5 f. 7 F.2d 142, 153, cert, denied, • 1973, 413 U.S.

922, r ' 2d 1 044. 93 A. Ct! 3052.------- ----------------

employs less than the maximum busing possible, since it anticipate.

, /7 . ' •

a significant reduction in elementary school student busing in

the year of implementation. Accordingly, I would direct that xn

analyzing remedies for desegregation of the Montgomery schools on

renamd, the district court should consider the implementation of

additional busing as necessary to accomplish new zoning, pairing,

30/

or clustering.

30/

— of

Significantly, the extent — in terms of the number of

pupils involved,and apparently the length of the trips

additional elementary student busing envisioned in conncctior

with the plaintiffs-intervenors' plan very closely parallel^

- 34(a)-

I

fn continued

increase in elementary school busing under the desegrega-

•tion plan implemented in Swann, as reflected in the opinions

in the Supreme Court, 4 02 U.S. at 29-31; 20 I..Ed.2d at 574-

7.5; 91 S.Ct. a t ____, and the Fourth Circuit, 1970, 431 F.2d

130, 144-47. ' ' '

To summarize, I would hold that the district court erred

in adopting the School Board plan, because that plan falls short

of the constitutional mark, and because there is no indication of

the unworkabil'ity of a Constitutional remedy. I do not believe

the district court's result can be upheld on any of the arguments

advanced, whether independently or cumulatively considered. If

there be no other way to desegregate, the

tools of pairing and clustering must be used to relieve the bar-

J, /7 ■

ricaded tmd beleaguered blacks from their school garrisons. These

mixing mechanisms have received judiciiil blessing, and they must-

be employed unless manifestly unusable for constitutional rea

sons. Other innovations may be considered. Nothing to achieve

the constitutional mandate to desegregate can be avoided because

of whimsy, white flight and fright, inconvenience, annoy

ance or any other actual or conjured excuse. Desegregation of

education is a constitutional necessity and not an optional luxury

and bland generalities will not suffice to justify segregated

schools.

- 35 -

1 would be unwilling to require the immediate implementa

tion of any of the alternative elementary school plans presented,

however, in light of the district court's determination that the

plans of the plaintiffs and plaintiffs-intervenors were generated

to achieve racial ratios beyond and in contravention of the man

date of Swann, in light of the state of the record, and in light

•of the opportunity remaining for the district court to refine and

31/

meld the various plans before it. Rather I would remand the

case to the district court for further proceedings to develop a

proper plan. Wo have in

, /

H 7 ~~ rCf. Adams v. Rankin County Bd. of Educ., 5 Cir. 1973, 485

F.2d 324, 326; Andrews v. City of Monroe, 5 Cir. 1970, 425

F. 2 d 1017, 102 3.

aaj36

the pact required specific and detailed finings to accompany

the district court's selection of a desegregation remedy that

promises to he less effective than alternative plans for estab-

lishing a unitary school system. This requirement is

meant to secure to the reviewing court the full ad

vantages of the factual appraisals and perspective of the particu

larly well-situated trial court, in order to

maximize the benefits of the district court's informed discretion.

iFy

See, e.g. , 7\dams v. Rankin County Bd. of Educ., 5 Cir. 1973

405 E.2d 324, 326; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ. , 5 Cir.

1972, 457 F. 2d 1031, 3.097; .Andrews v.' City of Monroe, 5 Cir. 1970,

425’ F.2d 1017, 1021; cf. also, Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Bd.

/

of Educ.;'1971, 404 U.S. 1221, 1226-27, 31 1,. Ed. 2d 441, 446, 92

S. Ct. 1236, ____ (Burger, C.J., in chambers).

Cf. Brown v. Board of Educ. of Topeka, 1955, 349 U.S. 294, 299-300,

99 L.Ed.2d 1003, 1105-06, 75 S.Ct. 753,____(Brown XI) . Thus I

would direct tliat, if the district court should approve on remand

a plan less than fully effective in establisliing a unitary school

system in Montgomery County, it must support its conclusion

with precise and detailed

'-O

findings of fact, keeping in mind Swann';; heavy burden upon

school officials to legitimate any less than thorough desegrega-

33/

tion plan on grounds of unworkability:

All things being equal, with no history of dis

crimination, it might well be desirable to as ign

pupils to schools nearest their homes. But all

things are not equal in a system that has been

deliberately constructed and maintained to enforce

racial segregation. The remedy for such segregation

may be administratively awkward, inconvenient, emd

even bizarre in seme situations and may impose burdens

on some; but all awkwardness and inconvenience cannot

be avoided in the interim period when remedical adjust

ments are being made to eliminate the dual school

systems.

/

402 U.S,'. at 28, 28 L. Ed. 2d at 573, 91 S. Ct. at _______. Many

practicalities affect the judgment and aims of school authorities

in pursuing their daily occupation of maintaining a pragmatic

educational system. But when the constitutionally mandated

establishment of a unitary school system rests in the balance,

workaday practicalities are no longer determinative factors.

33/ Sec aĵ so

/ Green v. School Bd. of New Kent County, 1960, 391 U.S. 430

439, 20 L. Ed. 2d 716, 724, 88 S. Ct. 1609, _____ .

1<hc conservation of such daily efficiencies may have been a con

sidered objective in the days of Plessy v. Ferguson, 1096, 163

j.S. 337, 41 L.Ed.256, 5. Ct. , but Brown v. Board of

(Brown 1) ,

Kduc. of Topeha, 1934, 347 U.S. 4B3, 90 L. Ed.073, 74 S. Ct.606 /

post-adoleseen t

has tahen us down a new road. Brown and its/progeny have imposed

upon school authorities and courts an

such

affirmative duty to see that

/stumbling blochs in the path of desegregation are relegated to a

34 ,

footnote in history. As we observed in a prior Montgomery case,

‘"Ibis obligation is unremitting, and there can be no abdication,

no matter how temporary." A school board's plan may have any num-

ber of advantages when 'appraised in ordinary perspective, but

these give way where- they impede the progress of desegregation;

, / /

convenience as well as cu:;tom must bend to constitutional pro

scription.

Given my resolution of this aspect of the attach on the.

would

School Board’s plan for the elementary grades, I /find it un

necessary to consider at this time whether that plan imposes a

discriminatorily harsh burden on the black students.

34,

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 5 Cir. 1970, 4.-9

F.2d 302, 306.

*

Junior High School Plan

The junior high school student assignment plan in effect

in the Spring of 1974 left over half of the black students in

7 junior high schools which were over- 85% black. The School

Board plan, as implemented by the district court, proposed to

reduce this concentration through rezoning, peripheral reassign-

ments, and the elimination of three black schools; the district

court projected that McIntyre Junior High, enrolling 792

• of the County's black junior high students (18%) would remain the

only junior high facility more than 80% black under the School

/, /

’ / '

Board plan.

III

The district court's opinion, following the style

of the School Board plan, treats the some 252

(233 black, 19 white) junior high school students in

attendance at the Montgomery County High facility as

senior high school students. The apparent premise

to this treatment is that "[i]t is conceded by all.

parties that Montgomery County High School . - - cannot be

effectively desegregated because of its isolation." 377 F.

Supp. at 1138, n. 37. This conclusion is not con

tested here, although the plaintiffs-intervenors'

plan did propose to reduce the junior high class at

Montgomery County High from 92% to 82% black. My

-40 -

figures follow the style of the district court.

Both the plaintiffs and plaintiffs-intervenors submitted

alternative plans for desegregation at the junior high level. The

School '

plaintiffs proposed to modify the basic/Board plan through addi

tional busing to achieve a closer racial balance at McIntyre and

two other junior, high schools left substantially black under the

Board plan, Bellingrath and Baldwin. The plaintiffs-intervenors

projected a 65% black student body at McIntyre, and a less than

60% black enrollment cit each of 8 other junior high schools with-

strip zones, with transportation to be provided within each zone

where necessary. In adopting the School Board plan for the

junior high schools, the district court dismissed these alterna

tive proposals as too inflexibly wedded to abstract racial bal

ancing, and suggested that they were unfeasible. Emphasizing

the isolation of McIntyre as the only virtually all-black junior

high remaining under the School Board plan, the district court

held that "under the circumstances that exist in the Montgc

7/

in the City, under a plan of new elongated but continuous

school system" no further requirement of desegregation could be

36/

imposed upon the County. 377 F.Supp. at 1139.

21/ The district court found that the plaintiffs'

. proposed plan would require reassignment of