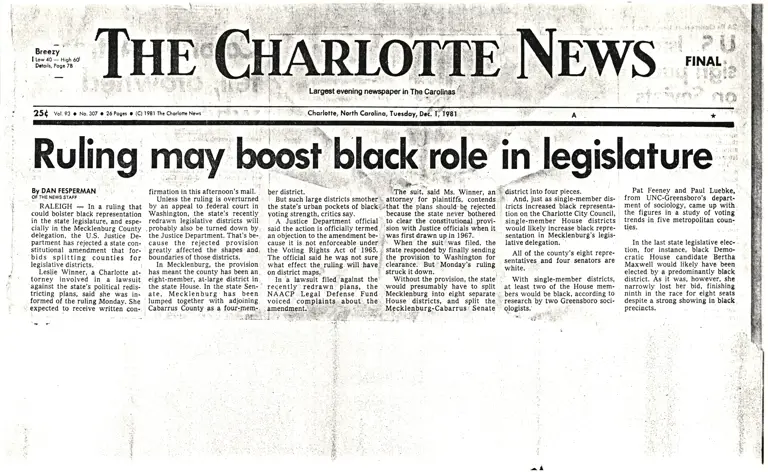

Ruling May Boost Black Role in Legislature News Clipping

Press

December 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Ruling May Boost Black Role in Legislature News Clipping, 1981. 5f5561ae-e092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3a60e863-d085-44e4-967e-ff35612fdc7e/ruling-may-boost-black-role-in-legislature-news-clipping. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

-lBreezy

I tow 40 - Hish 60!

Drloils, Poge 7B

.'i

iirl

i,,;J

25( vot.93 o No. 307 o .26 Pogct o (C) lgBl The Chorlone Newi Chorlolte, North Corolino, Tuesdoy, D.i. I; lgSl *A

lCIy

By DAN FESPERMAN

OF THE NEWS STAFF

RALEIGH - In a ruling that

could bolster black representation

in the state legislature, and espe-

cially in the Mecklenburg County

delegation, the U.S. Justice De-

partment has rejected a state con-

stitutional amendment that for-

bids splitting counties for

legislative districts.

Leslie Winner, a Charlotte at-

torney involved in a lawsuit

against the state's political redis-

tricting plans, said she was in-

formed of the ruling Monday. She

expected to receive written con-

firmation In this afternoon's mail.

Unless the ruling is overturned

by an appeal to federal court in

Washington, the statels recently

redrawn legislative districts will

probably also be turned down by

the Justice Department. That's be-

cause the rejected provision

greatly affected the shapes and

boundaries of those districts.

In Mecklenburg, the provision

has meant the county has been an.

eight-member, at-large district in

the state House. In the state Sen-

-

ate, Mecklenburg has been

lumped together with adjoining

Cabarrus County, as a four-mem-

ber district.

But such large districts smother

the state's urban pockets of black.

voting strength, critics say.

A Justice Department official

said the action is officially termed

an objection to the amendment be-

cause it is not enforceable under

the voting Rights Act of 1965.

The official said he wap not sure

what effect the ruling will have

on district maps.

In a lawsuit filed against the

reqently redrawn plans, the

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

voiced complaints about the

amendment. ..'

, ,,t

t blqct'iiole

" lrn.tJ"ii,

saio Ms. winner, an

iqlegislqture

district into four pieces.

' And, just as single-member dis-

tricts increased black representa-

tion on the Charlotte City Council,

single-member House districts

would likely increase black repre-

sentation in Mecklenburg's legis-

lative delegation.

All of the county's eight rePre-

sentatives and four senators are

white.

With single-member districts,

at least two of the House mem-

bers would be black, according to

research by two Greensboro soci-

q.logists.'

.-i'

Pat Feeney and Paul Luebke,

f rom UNC-Grgensboro's depart.

ment of sociology, came up wiih

the figures in a study of voting

trends in five metropolitan coun-

ties.

In the last state legislative elec-

tion, for instance, black Demo-

cratic House candidate Bertha

Maxwell would likely have been

elected by a predominantly black

district. As it was, however, she

narrowly lost her bid, finishing

ninth in the race for eight seats

despite a strong showing in black

precincts.

attorney for plaintiffS, contends

."that the plans should be rejected

because the state never bothered

to clear the constitutional provi-

sion with Justice officials when it

.was first drawn up in 1967.j' When the suit was filed, the

state responded by finally sending: the provision to Washington for

clearance. But Monday's ruling

struck it down.

Without the provision, the state

would presumably have to split

Mecklenburg into eight separate

House districts, and split the

Mecklenburg-Cabarrus Senate

rl