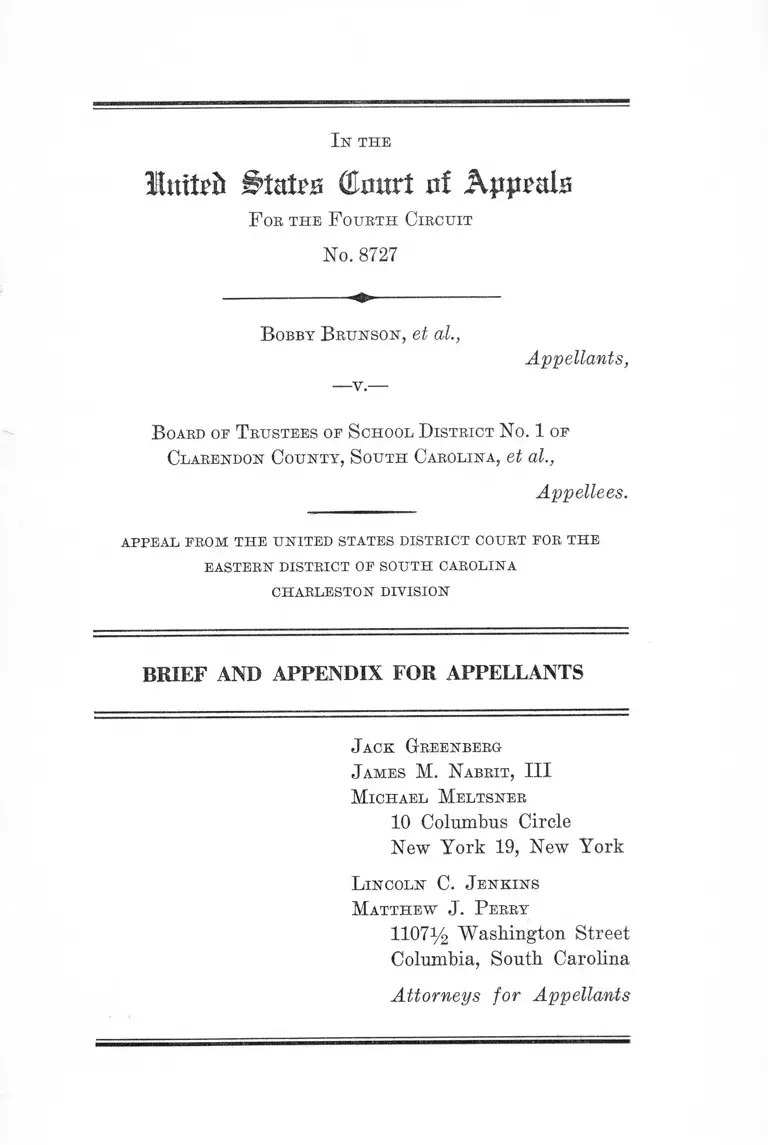

Brunson v Board of Trustees of School District No 1 of Clarendon County South Carolina Appendix for Appellants

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1962

37 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brunson v Board of Trustees of School District No 1 of Clarendon County South Carolina Appendix for Appellants, 1962. d2ac4afa-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3ae540d0-cdd3-4b7c-aa08-aa2c61eeb336/brunson-v-board-of-trustees-of-school-district-no-1-of-clarendon-county-south-carolina-appendix-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Ittifpfi (Emtrt of A*ijn>als

F ob the F ourth Circuit

No. 8727

I n th e

B obby B runson, et al.,

—v.—•

Appellants,

B oard of T rustees of S chool D istrict No. 1 of

Clarendon County, S outh Carolina, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM T H E U N ITED STATES D ISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOU TH CAROLINA

CH ARLESTON DIVISION

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

L incoln C. J enkins

Matthew J. P erry

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX TO BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of the Case ............................................ 1

Statement of Facts ........................................................ 5

Questions Involved ........................................................ 7

A bgument :

Negro School Children and Their Parents Are

Entitled to Join Together, on Behalf of Them

selves and Others Similarly Situated, in Order

to Seek Injunctive Relief Against the Mainte

nance of Discriminatory Pupil Assignment Pro

cedures ..................................................................... 8

Conclusion ......................................................................... 12

T able op Cases

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955) .. 11,12

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4th Cir. 1959) 11

Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960) ......... 10

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763

(5th Cir. 1959) ............................................................. 10

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke,------

F. 2 d ------ (4th Cir. May 22, 1962) .......................9,10,12

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ..... '...................................... 10

11

PAGE

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 P. 2d

370 (5th Cir. 1960) .... 10

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County,

— F. 2 d ------ (4th. Cir. June 12, 1962) ...............9,11,12

Northeross v. Board of Education of the City of

Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) ................ 10

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Relevant Docket Entries .............................................. la

Complaint ....................................................................... 2a

Motion to Strike .............................................................. 12a

Motion to Dismiss ......................................................... 13a

Opinion and O rder............. 14a

Notice of Appeal ........................................................... 20a

I n th e

Hutted (ta r t nf Appeals

F ob the F ourth Circuit

No. 8727

B obby B runson, et al.,

Appellants,

B oard oe T rustees of S chool D istrict No. 1 of

Clarendon County, South Carolina, et al.,

Appellees.

appeal from the united states district court for the

EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

CHARLESTON DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order (lla -lT a)1 entered May

31, 1962 striking the names of all the plaintiffs from the

complaint save one minor plaintiff and striking all the

allegations of the complaint inappropriate to a personal

action by said one minor plaintiff (19a).

This is an action for injunctive relief brought by the

plaintiff-appellants, Negro school children and parents in

Clarendon County, South Carolina, against the Board of

Trustees of School District No. 1 of Clarendon County,

South Carolina, the County Superintendent of Education

1 Citations are to the appendix to this brief.

2

and the District Superintendent of Education. This appeal

is brought under 28 U. S. C. §1291.

The complaint was filed on April 13, 1960 by 42 Negro

school children eligible to attend the public schools of

School District No. 1 of Clarendon County, South Carolina,

and their parents (2a-lla) as a class action on behalf

of themselves and on behalf of other adults and minors

similarly situated, pursuant to the provisions of Rule

23(a)(3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (4a).

Jurisdiction was invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1343(3),

the action being authorized by 42 IT. S. C. §1983 to redress

the deprivation of rights secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States and by 42

U. S. C. §1981 providing for the equal rights of citizens

(4a).

The complaint identified appellees, the Board of Trustees

of School District No. 1, the County Superintendent of

Education and the District Superintendent of Education,

as generally maintaining and supervising the public schools

of School District No. 1 pursuant to the direction of the

Constitution and laws of the State of South Carolina (6a).

The complaint alleged that the defendants had main

tained and continued to maintain a biracial school system

in which school attendance and assignment of school per

sonnel was determined by race and color and that certain

schools were restricted to white school children and per

sonnel and others to Negro school children and personnel

(7a). Appellants alleged that the maintenance of a biracial

school system resulted in injury to appellants and the class

which they represented in violation of rights guaranteed

by the Constitution and laws of the United States (7a-10a).

Appellants sought a permanent injunction enjoining ap

pellees from operating a biracial school system, maintain

ing dual school zones, assigning students and subjecting

3

students to assignment transfer or admission standards

on the basis of race (10a). In the alternative, appellants

prayed that appellees be directed to submit a plan for the

reorganization of the school system of Clarendon County

on a nonracial basis (11a).

On May 3, 1960, appellees filed a Motion to Strike (12a)

“ (1) from the caption of the complaint the names of all

of the plaintiffs except ‘Bobby Brunson’ and (2) from the

body of the complaint all of the allegations unrelated to

the cause of action in behalf of ‘Bobby Brunson’ as sole

plaintiff” on the ground that “ no class action within the

meaning of Rule 23(a)(3) is alleged and therefore if any

cause of action is stated in behalf of any plaintiff it is one

for individual relief, which may be entertained only if all

immaterial allegations and all nonessential parties are

eliminated from the action” .

Also on May 3, 1960, appellees filed a Motion to Dismiss

on the ground that the Court lacks jurisdiction and the

complaint fails to state a claim upon which relief can be

granted in that the complaint does not allege a class action

within the meaning of Rule 23(a)(3) of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure (13a).

On May 14, 1962, two years after the filing of the motion

to strike and motion to dismiss, the Court held a hearing

on both motions. On May 31, 1962, the Court, Judge C. C.

Wyche (sitting by Designation), filed its opinion and

ordered that the names of all of the appellants other

than Bobby Brunson be stricken from the complaint as well

as all of the allegations of the complaint inappropriate

to a personal action by Bobby Brunson (19a). In con

cluding that this action was not properly brought as a

class action under Rule 23(a)(3), the Court determined

that there was no common question of fact or unresolved

4

common question of law and, therefore, a class action was

inappropriate (18a).

As to a common question of law, the Court had this to

say:

. [DJecisions make it clear that any common

question of law has been settled. The defendant may

not deny to any plaintiff on account of race the right

to attend any school which it maintains. That law has

been established not only in controlling decisions of

the Fourth Circuit but also in an action involving

this very school district to which several of the plain

tiffs here were parties and in which the School Board

was a defendant. Briggs v. Elliot, 132 F. Supp. 776,

777” (17a).

In passing to the issue of a common question of fact the

Court stated:

• In determining the school to which a pupil is

entitled to go, a School Board must consider a great

many factors unrelated to race, such as geography,

availability of bus transportation, availability of class

room space, and scholastic attainment in order to

perform the Board’s duty to promote the best interests

of education within the district and insofar as possible

place the child in the school where he has the best

chance to improve his education. ‘School authorities

have the primary responsibility for elucidating, as

sessing and solving these problems.’ Briggs v. Elliott,

349 U. S. 294. There is no allegation in the complaint

showing that the factual situation with reference to

each of the plaintiffs is the same. Undoubtedly the

plaintiffs reside in different places, they are of dif

ferent ages, they are of different scholastic attainment.

South Carolina has provided a pupil placement statute

5

which permits any child desiring to attend a school

other than the one to which he has been assigned to

proceed through administrative channels to obtain

placement in a different school of his choice. This

statute provides that the case of each child shall be

considered individually. 1952 Code, Sections 21-230,

21-247; Hood v. Board, 232 F. 2d 626, 286 F. 2d 236.

This statute is similar to the North Carolina statute,

the validity of which was sustained in Carson v. Board

of Education of McDowell County, 227 F. 2d 789

(1955), and in Carsonv. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (1956)”

(18a).

On June 21, 1962, plaintiffs filed Notice of Appeal from

the order of May 31, 1962 (20a).

Statement of the Facts

The forty-two Negro school children and their parents

and guardians who brought this action on behalf of them

selves and other adults and minors similarly situated are

all Negro citizens of the United States and residents of

the State of South Carolina, residing in School District

No. 1, Clarendon County (5a).

After the decision of the United States Supreme Court

in the School Segregation Cases, the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, on

July 15, 1955, issued its decree in the case of Briggs v.

Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955) providing

that the officials of what is now School District No. 1,

Clarendon County, comply with the decision and mandate

of the United States Supreme Court in the School Segre

gation Cases, namely, that they operate them on a non-

discriminatory basis, with race no longer as a standard of

6

school assignment. Plaintiff-appellants here allege in their

complaint that appellees have failed and refused to take

any steps to eliminate racial segregation in the school

system in accordance with the decree in Briggs v. Elliott,

supra and have steadfastly failed and refused to employ

a plan for the reorganization of the school system into

a unitary, nonracial school system as required by decisions

of the United States Supreme Court (7a).

It is alleged that appellants have each made written

application to defendants requesting reassignment to a

public school limited to attendance by white students only

to no avail (8a). Adult plaintiffs, some of whom were

plaintiffs in the aforementioned case of Briggs v. Elliott,

supra and all of whom by reason of their residing in

School District No. 1, would have benefited by the proper

implementation of the decree entered in that case on July

15, 1955, requiring that schools be operated on a non-

discriminatory basis, waited for over four years for the

defendants to begin complaince with the order of this

Court. On August 27, 1959, the appellants, through their

attorney, Lincoln C. Jenkins, Jr., wrote to appellee W. C.

Sprott, Chairman, Board of Trustees, School District No.

1, requesting assignment of their children to a school to

which a white child similarly situated to them would at

tend (8a). They received no reply to this request (8a).

Subsequently, on October 8, 1959, the adult plaintiffs called

upon appellee W. C. Sprott in writing to institute a plan

for the complete desegregation of the schools within his

jurisdiction. A reply from defendants dated October 13,

1959, indicated that appellants’ request came too late for

consideration by the Board, although the deadline referred

to in the Board’s reply had never been previously publicly

announced (8a).

7

It is alleged that the appellants have not exhausted the

administrative remedy provided by the South Carolina

School laws for the placement of pupils by trustees for the

reason that the remedy there provided is inadequate to

provide the relief sought by appellants in this case (9a).

Appellants alleged they have not exhausted the remedy

provided by the aforesaid pupil placement laws for the

further reason that the criteria set forth in these laws

for assigning children to school have been and are applied

by appellees only to Negro children seeking admission, as

signment or transfer (7a-10a). Furthermore, by the use

of a previously unannounced cutoff date, appellees have

prevented plaintiffs from employing the purported reme

dies under said law (8a-10a). Appellants alleged that act

ing under color of the authority conferred upon them by

the South Carolina laws for the placement of pupils by

trustees, defendants have continued to maintain and oper

ate a biracial school system in School District No. 1 of

Clarendon County; have used the provisions of these laws

to deny admission of Negro children to certain schools

solely because of race and color; and have used these laws

to defeat rather than attain full compliance with the deci

sions of the United States Supreme Court in the School

Segregation Cases (9a-10a). Plaintiffs alleged that defen

dants have not employed the pupil placement laws as a

means of abolishing state imposed race distinctions, nor

have they offered to plaintiffs, by means of the pupil as

signment, a genuine means of securing attendance at non-

segregated public schools (7a-10a).

Question Involved

Whether the Court below erred in determining that

forty-two Negro school children and their parents seeking

injunctive relief against the racially discriminatory policies

8

of a school board and its administrators on behalf of them

selves and others similarly situated could not join in a single

suit and maintain a class action under Rule 23(a)(3) of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure when plaintiffs al

leged discriminatory application and administration of

pupil assignment laws in a biracial school system.

ARGUMENT

Negro School Children and Their Parents Are En

titled to Join Together, on Behalf of Themselves and

Others Similarly Situated, in Order to Seek Injunctive

Relief Against the Maintenance of Discriminatory Pupil

Assignment Procedures.

Appellants alleged in the complaint that they had not

exhausted the administrative remedies provided by the

South Carolina pupil placement laws for the reason that

the criteria set forth in these laws for assigning children

to school have been and are applied by defendants only

to Negro children seeking admission, assignment or trans

fer ’ (9a). Appellants alleged that the appellees maintained

a biracial school system under color of the authority con

ferred by the South Carolina pupil placement laws; em

ployed unannounced cutoff dates in order to prevent plain

tiffs from exhausting the remedies under the placement

laws; and employed said laws as a means to defeat rather

than to comply with the decisions of the United States

Supreme Court in the School Segregation Cases (10a).

Appellants prayed the court grant the following relief:

1. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from operating a biracial

school system in School District No. 1 of Clarendon

County;

9

2. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from maintaining a dual

scheme or pattern of school zone lines based upon race

and color;

3. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from assigning students to

schools in Clarendon County on the basis of the race

and color of the students;

4. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from subjecting Negro chil

dren seeking assignment, transfer or admission to the

schools of Clarendon County, to criteria, requirements

and prerequisites not required of white children seek

ing assignment, transfer or admission to the schools

of Clarendon County.

In the alternative, plaintiffs pray that this Court

enter a decree directing defendants to present a com

plete plan, within a period of time to be determined

by this Court, for the reorganization of the school

system of Clarendon County, South Carolina, on a

unitary, nonracial basis which shall include the as

signment of children on a nonracial basis, the drawing

of school zone lines on a nonracial basis, and the

elimination of any other discriminations in the opera

tion of the school system based solely upon race and

color. Plaintiffs pray that if this Court directs defen

dants to produce a desegregation plan that this Court

will retain jurisdiction of this case pending approval

and full implementation of defendants’ plan (lOa-lla).

This case is, therefore, like Green v. School Board of the

City of Roanoke,------F. 2 d ------- (No. 8534, May 22, 1962),

and Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County,

____. F. 2 d ____ (No. 8535, June 12, 1962), in which this

10

Court condemned the operation of pupil assignment laws

in school systems with dual racial zones. The complaint

raises the very issues the Court decided in Green when it

said: “Because the initial school assignments are made on

a racial basis, full compliance by the plaintiffs with the

transfer procedures cannot repair the discrimination to

which they have been and are subjected.”

Appellants, therefore, are under no obligation to pursue

administrative remedies. “ To insist, as a prerequisite to

granting relief against discriminatory practices that the

plaintiffs first pass through the very procedures that are

discriminatory would be to require an exercise in futility,”

Green, supra. See Jones v. School Board of City of Alexan

dria, 278 F. 2d 72, 77 (4th Cir. 1960); Farley v. Turner,

281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960) ; Norther oss v. Board of

Education of the City of Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir.

1962); Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d

370, 372-75 (5th Cir. 1960); Gibson v. Board of Public

Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763, 766-67 (5th Cir. 1959).2

This Court has already decided that appellants, faced

with a pupil assignment law administered in a manner

offensive to their constitutional rights, may join together

in one proceeding to obtain relief on behalf of themselves

and others similarly situated pursuant to the provisions of

Buie 20(a) and Buie 23(a)(3) of the Federal Buies of

Civil Procedure.

In Green, supra, the Court stated:

. . . the individual appellants are entitled to relief

and also they have the right to an injunction on behalf

of the others similarly situated.

2 Sood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School District, 286 F. 2d

236 (4th Cir. 1961); Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 277

F. 2d 789 (4th Cir. 1955) and similar eases are, therefore, inapplicable.

11

In Marsh, supra, the Court held that:

. . . the plaintiffs are entitled to a declaratory judg

ment that the defendants are administrating the Pupil

Assignment Act in an unconstitutional manner and to

an injunction against the further use of racially dis

criminatory criteria in the assignment of pupils to

school.

The most explicit approval of this procedure appears

in Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780, 783 (4th Cir. 1959).

In Covington, this Court affirmed a motion to dismiss on

the ground that plaintiffs had failed to exhaust their

administrative remedies and had not shown that the Pupil

Assignment Law had been utilised so as to perpetuate

segregated schools. In discussing the rights of Negro

school children when subjected to discriminatory assign

ment criteria, the Court said:

If after the hearing and final decision he is not

satisfied and can show he has been discriminated

against because of his race, he may then apply to the

federal court for relief. In the pending case, however,

that course was not taken . . . and the decision of the

District Court in dismissing the case was therefore

correct. This conclusion does not mean that there

must be a separate suit for each child on whose behalf

it is claimed that an application for reassignment has

been improperly denied. There cam, be no objection to

the joining of a number of applicants in the same suit

as has been done in other cases. (Emphasis added.)

The decree in Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D.

S. C. 1955), in which some of the adult appellants in the

instant suit were plaintiffs, did not adjudicate the ques

tion of the constitutionality of appellees’ administration

of the South Carolina pupil placement laws. Nor did it

12

grant the specific relief which appellants seek here. The

decree in Briggs v. Elliott, supra, was but a general injunc

tion prohibiting racial discrimination in the administration

of the schools and not a final determination of the legality

of the assignment and transfer practices appellants chal

lenge.

Appellants have alleged that the appellees have ad

ministered pupil placement laws unconstitutionally. They

have been denied the opportunity to make the required

showing of discriminatory application delineated by Marsh

v. County School Board of Roanoke County, supra, and

Green v. Roanoke City School Board, supra. Appellants,

on behalf of themselves and the class they represent, have

a common legal interest in proving they are subject to

unconstitutional racial zoning and racial assignment and

transfer criteria by reason of appellees’ administration

of the South Carolina pupil placement laws.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, appellants pray

the judgment below be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

L incoln C. Jenkins

Matthew J. Perry

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

APPENDIX

Relevant Docket Entries

Civil Action No. 7210

---------------------------------------

B obby B runson, et al.,

Appellants,

B oard of T rustees of S chool D istrict No. 1 of

Clarendon County, S outh Carolina, et al.,

Appellees.

Bate Proceedings

1960

4-13 Summons and Complaint.

4-13 7 copies to Marshal for Service.

4-14 Marshal’s Returns (6) of Service on L. Richard

son, J. W. Sconyers, W. A. Brunson, C. N. Plow-

den, W. C. Sprott, and L. B. McCord on 4-14-60.

4- 19 Marshal’s Return of Service on C. E. Buttes on

4-15-60.

5- 3 Defendants’ Motion to Strike.

5-3 Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss.

5-14-62 Hearing on motion to dismiss and to strike. Coun

sel to file briefs and case taken under advisement.

5-31-62 Opinion and Order that names of all of the plain

tiffs other than Bobby Brunson be stricken from

caption and that plaintiff Bobby Brunson shall

have 20 days from date from order to file an

amended complaint.

5- 31-62 Copies to counsel.

6- 21-62 Notice of Appeal.

6-21-62 Appeal Bond.

6- 21-62 Designation of Record on Appeal.

7- 24-62 Appeal Record to USCA.

2a

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the E astern D istrict oe S outh Carolina

Charleston D ivision

(Filed: April 13,1960)

Complaint

B obby Brunson, E lizabeth Brunson and E llis Brunson,

by McQueen Brunson, their father and next friend,

— and—

T isbia E. Delaine, a Minor by Leo Delaine, her father

and next friend,

— and—

Eloise F elder, a Minor, by Nora Felder, her mother

and next friend,

— and—

Blease C. Gibson, Jr., T homas Gibson, Evelyn M. Gibson

and F rancis E. Gibson, by Frances Gibson, their mother

and next friend,

— and—

J oseph Gipson, F rancina Gipson, and Calvin Gipson, by

Johnnie Gipson, their father and next friend,

—and—

Susan J. H ilton, Bessie I. H ilton, Edward P. H ilton and

Charles M. H ilton, by W illiam H ilton, their father

and next friend,

—and—

H arry G. McDonald and R itta McDonald,

their father and next friend,

— and—

J eremiah Oliver, Jr. and Mary Oliver, their mother

and next friend,

— and—

3a

V idel P earson, Deleware P earson, Harold Pearson and

Carrie A. Pearson, by Levi P earson, their father and

next friend,

— and—

Cleola R agin, R obert L. R agin, Moses Ragin, H enry J.

R agin, L ucretia R agin and W illie J. R agin, by Minnie

R agin, their mother and next friend,

—and—

Glenn R agin, a Minor by W illiam Ragin, his father

and next friend,

—and—

Jackson D. R ichardson and J ohnnie F. Richardson,

by L ee R ichardson, their father and next friend,

—and—

T helma Stukes, E thel Stukes, L ionel Stukes, Marion

Stukes, A bel Stukes, R ochelle Stukes and Marcia

Stukes, by L adson Stukes, their father and next friend,

—and—

Della T indal, a Minor, by L awrence T indal,

her father and next friend,

—and-—

E manuel R ichardson, a Minor by Luchresher R ichardson,

his father and next friend,

Plaintiffs,

B oard of Trustees of School District No. 1 of Clarendon

County, South Carolina.; L. B. McCord, County Super

intendent of Education; C. E. Buttes, District Super

intendent of Education; W. C. Sprott, Chairman, Board

of Trustees; C. N. Plowden, W. A. Brunson, J. W.

Sconyers and L. R. R ichardson, Members of the Board

of Trustees,

Defendants.

Complaint

4a

1. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, §1343(3), this being an action

which is authorized by law, Title 42, United States Code,

§1983, to be commenced by any citizen of the United States

to redress the deprivation under color of state law, statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom or usage of rights, privileges

and immunities secured by the Constitution and laws of the

United States. The rights here sought to be redressed are

rights guaranteed by the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States and by Title 42, United States Code,

§1981.

2. This is a proceeding for a permanent injunction en

joining defendants from continuing to pursue the policy,

practice, custom and usage of operating a biracial school

system in School District No. 1, Clarendon County, South

Carolina, in violation of rights secured to plaintiffs by the

Constitution and laws of the United States referred to

above.

3. This is a class action brought by the adult plaintiffs

for the minor plaintiffs on behalf of themselves and on be

half of other adults and minors similarly situated, pursu

ant to the provisions of Rule 23(a)(3) of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure. The members of this class are all adult

Negro citizens and their minor children of the State of

South Carolina who reside in School District No. 1, Claren

don County. The minors are all eligible to attend the public

schools in School District No. 1 of Clarendon County, South

Carolina, and the members of the class are all similarly

affected by the action of the defendants in maintaining and

operating the public school system of School District No. 1,

Clarendon County, on a racially segregated basis. There

Complaint

5a

are involved common questions of law and fact affecting

tlie rights of all other Negro children eligible to attend the

public schools of School District No. 1, Clarendon County,

and their respective parents and guardians, who are so

numerous as to make it impracticable to bring all before

the Court, but whose interests are adequately represented

by plaintiffs.

4. The adult plaintiffs in this ease are all citizens of the

United States and of the State of South Carolina, residing

in School District No. 1, Clarendon County. Each adult

plaintiff is the parent of one or more minor children who

are eligible to attend the public schools in District 1 of

Clarendon County. Each minor plaintiff is likewise a citi

zen of the United States and of the State of South Caro

lina, residing in District No. 1, Clarendon County.

5. The plaintiffs in this case are Bobby Brunson, Eliza

beth Brunson and Ellis Brunson, minors, by their father

and next friend, McQueen Brunson; Tisbia E. Delaine, a

minor, by her father and next friend, Leo Delaine; Eloise

Felder, a minor, by her mother and next friend, Nora

Felder; Blease C. Gibson, Jr., Thomas Gibson, Evelyn M.

Gibson and Francis E. Gibson, minors, by their mother and

next friend, Frances Gibson; Joseph Gipson, Francina

Gipson and Calvin Gipson, minors, by their father and next

friend Johnnie Gipson; Susan J. Hilton, Bessie I. Hilton,

Edward P. Hilton and Charles M. Hilton, minors, by their

father and next friend, Charles M. Hilton; Harry G. Mc

Donald and Ritta McDonald, minors, by their father and

next friend, John McDonald; Jeremiah Oliver, Jr. and Mary

Oliver, minors, by their mother and next friend, Mary J.

Oliver; Videl Pearson, Deleware Pearson, Harold Pearson

and Carrie A. Pearson, minors by their father and next

Complaint

6a

Complaint

friend, Levi Pearson; Cleola Ragin, Robert L. Ragin, Moses

Ragin, Henry J. Ragin, Lueretia Ragin and Willie J. Ragin,

minors, by their mother and next friend, Minnie Ragin;

Glenn Ragin, a minor, by his father and next friend,

William Ragin; Jackson D. Richardson and Johnnie F.

Richardson, minors, by their father and next friend, Lee

Richardson; Thelma Stakes, Ethel Stukes, Lionel Stukes,

Marion Stakes, Abel Stakes, Rochelle Stakes and Marcia

Stakes, minors, by their father and next friend, Ladson

Stakes; Della Tindal, a minor, by her father and next friend,

Lawrence Tindal, and Emanael Richardson, a minor, by

his father and next friend, Lnchresher Richardson.

6. Defendant L. B. McCord is County Snperintendent of

Edacation of Clarendon Coanty, Soath Carolina, inclading

School District No. 1, and holding office parsaant to the

laws of the State of Soath Carolina.

7. Defendant C. E. Battes is District Superintendent of

Edacation in School District No. 1 of Clarendon Coanty.

Defendant W. C. Sprott is Chairman of the Board of

Trastees of School District No. 1. Defendants C. N. Plow-

den, W. A. Branson, W. W. Sconyers and L. Richardson

are members of the Board of Trastees of School District

No. 1.

8. The defendants maintain and generally sapervise, as

indicated by their titles, the pablic schools in School Dis

trict No. 1 of Clarendon Coanty, Soath Carolina, acting

parsaant to the direction and anthority contained in state

constitational provisions and statates, and as snch are

officers of the State of Soath Carolina enforcing and exer

cising state laws and policies. This sait is broaght against

the defendants in their official and individnal capacities.

7a

9. Acting under color of the laws of the State of South

Carolina, the defendants have pursued and are presently

pursuing a policy, practice, custom and usage of operating

a biracial school system in District No. 1 of Clarendon

County. The biracial school system operated by defendants

consists of a system of elementary and high schools limited

to attendance by white children only. Said schools are

staffed by white teachers, white principals, and while lo

cated in various parts of the district, may be attended by

white children only. The defendants also maintain a sys

tem of schools limited to attendance by Negro children

only. These schools, likewise located in various parts of

the district, are staffed entirely by Negro personnel: the

teachers are all Negroes and the principals are all Negroes.

Attendance at the various schools is determined by race

and color and the assignment of personnel is determined

by race and color of the children and the race and color of

the personnel.

10. After the decision of the United States Supreme

Court in the School Segregation Cases, the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina,

on July 15, 1955, issued its decree in the case of Briggs v.

Elliott providing that the officials of School District No. 1,

Clarendon County, comply with the decision and mandate

of the United States District Court in the School Segrega

tion Cases, namely, that they operate them on a nondis-

criminatory basis, with race no longer as a standard of

school assignment. Defendants have failed and refused

to take any steps to eliminate racial segregation in the

school system and have steadfastly failed and refused to

employ a plan for the reorganization of the school system

into a unitary, nonracial school system as required by said

decisions.

Complaint

8a

11. Plaintiffs residing in School District No. 1 have each

made written application to the appropriate defendant re

questing reassignment to a public school limited to at

tendance by white students only, to no avail. Adult plain

tiffs, some of whom were plaintiffs in the aforementioned

case of Briggs v. Elliott, and all of whom by reason of their

residing in School District No. 1, would have benefited by

the proper implementation of the decree entered in that

case on July 15,1955, requiring that schools be operated on

a nondiscriminatory basis, waited for over four years for

the defendant to begin compliance with the order of this

court. On August 27, 1959, the plaintiffs, through their

attorney, Lincoln C. Jenkins, Jr., wrote to defendant W. C.

Sprott, Chairman, Board of Trustees, School District No.

1, requesting assignment of their children to a school to

which a white child similarly situated to them would attend.

They received no reply to this request. Subsequently, on

October 8, 1959, the adult plaintiffs in writing called upon

defendant W. C. Sprott to institute a plan for the complete

desegregation of the schools within his jurisdiction. A

reply from defendants dated October 13,1959, indicated that

plaintiffs’ request came too late for consideration by the

Board, although the deadline referred to in the Board’s

reply had never been previously publicly announced.

12. Plaintiffs, and the members of the class which they

represent, are injured by the operation of a biracial school

system for the Negro and white children in School District

No. 1, Clarendon County. The biracial school system is

predicated upon the theory that Negroes are inherently

inferior to white persons and, consequently, may not at

tend the same public schools attended by white children

who are superior. The plaintiffs, and members of their

class, are injured by the policy of assigning teachers, prin

Complaint

9a

cipals and other school personnel on the basis of the race

and color of the children attending a particular school and

the race and the color of the person to be assigned. Assign

ment of school personnel on the basis of race and color is

also predicated on the theory that Negro teachers, Negro

principals and other Negro school personnel are inferior

to white teachers, white principals and other white school

personnel and, therefore, may not teach white children.

13. The injury which plaintiffs and members of their

class suffer as a result of the operation of the biracial

school system in School District No. 1 of Clarendon County,

and as a result of the policy of assigning school personnel

on the basis of race is irreparable and will continue until

enjoined by this court. Any other relief to which the plain

tiffs and those similarly situated could be remitted would

be attended by such uncertainties and delays as to deny sub

stantial relief, would involve a multiplicity of suits, cause

further irreparable injury and occasion damage, vexation

and inconvenience, not only to plaintiffs and those similarly

situated, but to defendants as public officials.

14. The plaintiffs have not exhausted the administrative

remedy provided by the South Carolina School laws for the

placement of pupils by trustees for the reason that the

remedy there provided is inadequate to provide the relief

sought by plaintiffs in this case. Plaintiffs have not ex

hausted the remedy provided by the aforesaid pupil place

ment laws for the further reason that the criteria set forth

in these laws for assigning children to school have been

and are applied by defendants only to Negro children

seeking admission, assignment or transfer. Furthermore,

by the use of a previously unannounced cutoff date, de

fendants have prevented plaintiffs from employing the

Complaint

10a

purported remedies under said law. Plaintiffs allege that

acting under color of the authority conferred upon them by

the South Carolina laws for the placement of pupils by

trustees, defendants have continued to maintain and oper

ate a biracial school system in School District No. 1 of

Clarendon County, have used the provisions of this law

to deny admission of Negro children to certain schools

solely because of race and color, and have used this law to

defeat rather than attain full compliance with the decisions

of the United States Supreme Court in the School Segre

gation Cases. Defendants have not employed the pupil

assignment law as a means of abolishing state imposed race

distinctions, nor have they offered to plaintiffs by means

of the pupil assignment law a genuine means of securing

attendance at nonsegregated public schools.

Wherefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court

advance this cause on the docket and order a speedy hear

ing of this action according to law and after such hearing:

1. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from operating a biracial school

system in School District No. 1 of Clarendon County;

2. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from maintaining a dual scheme

or pattern of school zone lines based upon race and color;

3. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from assigning students to schools

in Clarendon County on the basis of the race and color of

the students;

4. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from subjecting Negro children

seeking assignment, transfer or admission to the schools of

Complaint

11a

Clarendon County, to criteria, requirements and prerequi

sites not required of white children seeking assignment,

transfer or admission to the schools of Clarendon County.

In the alternative, plaintiffs pray that this Court enter

a decree directing defendants to present a complete plan,

within a period of time to be determined by this Court, for

the reorganization of the school system of Clarendon

County, South Carolina, on a unitary, nonracial basis which

shall include the assignment of children on a nonracial

basis, the drawing of school zone lines on a nonracial basis,

and the elimination of any other discriminations in the

operation of the school system based solely upon race and

color. Plaintiffs pray that if this Court directs defen

dants to produce a desegregation plan that this Court will

retain jurisdiction of this case pending approval and full

implementation of defendants’ plan.

Plaintiffs pray that this Court will allow them their

costs herein and grant such further, other, additional or

alternative relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable

and just.

L incoln C. Jenkins

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Matthew J. P erry

371% South Liberty Street

Spartanburg, South Carolina

T hurgood Marshall

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Complaint

12a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Foe the E astern D isteict oe South Carolina

Ch arleston D ivision

C /A 7210

Motion to Strike

(Filed: May 3,1960)

[ same title]

Reserving their rights under a Motion to Dismiss, here

tofore filed, the defendants move the Court to strike (1)

from the caption of the complaint the names of all of the

plaintiffs except “ Bobby Brunson” and (2) from the body

of the complaint all of the allegations unrelated to the cause

of action in behalf of “ Bobby Brunson” as sole plaintiff,

including but not limited to the allegations of paragraphs

3, 4, and 5 and to portions of paragraphs 11, 12, 13 and 14,

and (3) those portions of the prayer not applicable to the

cause of action in favor of Bobby Brunson upon the ground

that no class action within the meaning of Rule 23(a)(3)

is alleged and therefore if any cause of action is stated in

behalf of any plaintiff, it is one for individual relief, which

may be entertained only if all immaterial allegations and

all non-essential parties are eliminated from the action.

David W. R obinson

R obinson, MoF adden & Moose

Attorneys for the Defendants

13a

UNITED STATES DISTKICT COURT

F ob the E astern D istrict of South Carolina

Charleston Division

C /A 7210

Motion to Dismiss

(Filed: May 3,1960)

{ same title}

----------------- -- --------------—— --- ------

The Defendants move the Court:

1. To dismiss the action on the ground that the Court

lacks jurisdiction in that the complaint fails to allege a

class action within the meaning of Rule 23(a)(3).

2. To dismiss the action because the complaint fails to

state a claim against the defendants upon which relief can

be granted in that a class action within the meaning of

Rule 23(a)(3) is not alleged.

David W. R obinson

R obinson, McF adden & Moore

Attorneys for the Defendants

14a

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the E astern District of South Carolina

Charleston D ivision

C /A 7210

Opinion and Order

(Filed: May 14,1962)

[ same title]

This cause is before me on the defendants’ motion to

dismiss upon the ground that the complaint fails to allege

a class action and on their alternate motion to strike from

the complaint all of the parties-plaintiff other than the

first named plaintiff and all of the allegations which are

unrelated to the first plaintiff’s cause of action upon the

ground that no class action is alleged.

These motions require an analysis of the complaint to

ascertain whether these allegations in the light of ap

plicable law allege a proper class action under Rule

23(a)(3).

The complaint is brought in behalf of a large number

of negro school children by their respective parents against

the Trustees of School District No. 1 of Clarendon County,

the Clarendon County Superintendent of Education, and

the District Superintendent of Education. The complaint

alleges that it is a class action under Rule 23(a) (3) brought

to protect rights under the 14th Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States and under the Civil Rights

Statute, 42 U. S. C. A. 1981. They allege that the defen

dants are operating a bi-racial school system in School

District No. 1 of Clarendon County; that the plaintiffs are

15a

being denied admission to certain schools solely on account

of race; and that the plaintiffs have not exhausted the

administrative remedy provided by the South Carolina

school laws because that remedy is inadequate. The com

plaint also alleges that some of the plaintiffs are the same

parties who were parties in Briggs v. Elliott (98 F. Supp.

529, 103 F. Supp. 920, 347 U. S. 483, 349 IT. S. 294, 132

F. Supp. 776), which action is still pending in this Court

before a Three-Judge Court. In effect, the complaint is

brought for the purpose of securing the admission of each

of the plaintiffs to one of the several white schools being

operated by the defendants in School District No. 1.

Rule 23 of the Rules of Civil Procedure of this Court

provides in pertinent part: “ Class Actions (a) Representa

tion. I f persons constituting a class are so numerous as

to make it impracticable to bring them all before the court,

such of them, one or more, as will fairly insure the ade

quate representation of all may, on behalf of all, sue or

be sued, when the character of the right sought to be

enforced for or against the class is * * * (3) several, and

there is a common question of law or fact affecting the

several rights and a common relief is sought.”

Moore, in his Federal Practice (2nd Edition), Vol. 3,

page 3442, designates the class of action referred to in

Rule 23(a)(3) as “ spurious class suits” . Spurious as here

used does not mean that such a suit may not be maintained

as a class action but it does mean that this group does not

fall within the traditional class action. Each plaintiff has

a “ several” cause of action. Joinder is permitted merely

because there is a “ common question of law or fact” . There

is a similarity between this type of class and the practice

of consolidating for trial two independent suits where there

is a similar legal or factual situation. For instance, tort

Opinion and Order

16a

actions on behalf of two occupants of an automobile in

jured in a single collision with a truck are frequently tried

together though neither plaintiff has any legal interest on

the damage to the other.

The inquiry here is to determine whether there is a

“ common question of law or fact” justifying the use of the

class procedure of Rule 23(a)(3). Turning first to the

question of whether there is present in this case any

unresolved common question of law, I should look to the

controlling decisions to ascertain whether there is now any

unresolved question of law.

In Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776, 777 (1955), the

Three-Judge District Court in interpreting the Supreme

Court decision in 347 U. S. 483, 349 U. S. 294, had this to

say about the legal issue: “Having said this, it is im

portant that we point out exactly what the Supreme Court

has decided and what it has not decided in this case. It

has not decided that the federal courts are to take over

or regulate the public schools of the states. It has not

decided that the states must mix persons of different races

in the schools or must require them to attend schools or

must deprive them of the right of choosing the schools

they attend. What it has decided, and all that it has de

cided, is that a state may not deny to any person on ac

count of race the right to attend any school that it main

tains. This, under the decision of the Supreme Court,

the state may not do directly or indirectly; but if the

schools which it maintains are open to children of all

races, no violation of the Constitution is involved even

though the children of different races voluntarily attend

different schools, as they attend different churches. Nothing

in the Constitution or in the decision of the Supreme Court

takes away from the people freedom to choose the schools

Opinion and Order

17a

they attend. The Constitution, in other words, does not

require integration. It merely forbids discrimination. It

does not forbid such segregation as occurs as the result

of voluntary action. It merely forbids the use of govern

mental power to enforce segregation. The Fourteenth

Amendment is a limitation upon the exercise of power by

the state or state agencies, not a limitation upon the free

dom of individuals.” (Emphasis added.)

This interpretation of the Supreme Court decision has

been followed consistently in the Fourth Circuit. School

Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen (C. A. 4),

240 F. 2d 59, 62 (1956); School Board of City of Newport

News, Va. v. Atkins (C. A. 4), 246 F. 2d 325, 327 (1957).

These decisions make it clear that any common question

of law has been settled. The defendants may not deny

to any plaintiff on account of race the right to attend any

school which it maintains. That law has been established

not only in the controlling decisions of the Fourth Circuit

but also in an action involving this very school district

to which several of the plaintiffs here were parties and in

which the School Board was a defendant. Briggs v. Elliott,

132 F. Supp. 776, 777.

There being no unresolved common question of law, I

shall next consider whether there is a common question

of fact. In determining the school to which a pupil is en

titled to go, a School Board must consider a great many

factors unrelated to race, such as geography, availability

of bus transportation, availability of classroom space, and

scholastic attainment in order to perform the Board’s duty

to promote the best interests of education within the dis

trict and insofar as possible place the child in the school

where he has the best chance to improve his education.

“ School authorities have the primary responsibility for

Opinion and Order

18a

elucidating, assessing and solving these problems.” Briggs

v. Elliott, 349 U. S. 294. There is no allegation in the

complaint showing that the factual situation with reference

to each of the plaintiffs is the same. Undoubtedly the

plaintiffs reside in different places, they are of different

ages, they are of different scholastic attainment. South

Carolina has provided a pupil placement statute which

permits any child desiring to attend a school other than

the one to which he has been assigned to proceed through

administrative channels to obtain placement in a different

school of his choice. This statute provides that the case of

each child shall be considered individually. 1952 Code,

Sections 21-230, 21-247; Hood v. Board, 232 P. 2d 626,

286 F. 2d 236. This statute is similar to the North Carolina

statute, the validity of which was sustained in Carson v.

Board of Education of McDowell County, 227 P. 2d 789

(1955), and in Carson v. Warlich, 238 F. 2d 724 (1956).

It is the individual who is entitled to the equal protection

of the law and if he is denied a facility which under the

same circumstances is furnished to another citizen, he

alone may complain that his constitutional privilege has

been invaded. He has the right to enforce his constitu

tional privilege or he has the right to waive it. No one

else can make that decision for him. McCabe v. A., T. £

S. F. By. Co., 235 U. S. 151; Williams v. Kansas City, Mo.,

194 F. Supp. 848, 205 F. 2d 47, c.d. 346 U. S. 826. Cf.

Machinists v. Street, 367 U. S. 740, 774 (1961).

Therefore, it is my conclusion that this action is not

properly brought as a class action under Rule 23(a)(3).

I have not found and the parties have not called to my

attention any precedent dealing with the disposition of a

complaint brought as a class action but where a cause of

action may exist in favor of an individual plaintiff. The

Opinion and Order

19a

defendants have moved to dismiss or, in the alternative, to

strike all of the parties-plaintiff except the first plaintiff

allowing the case to continue as an individual action in

behalf of that plaintiff. In my view the latter is the ap

propriate relief.

It is, therefore, Ordered and A djudged, (1) That the

names of all of the plaintiffs other than Bobby Brunson

are hereby striken from the caption of the complaint and

all of the allegations inappropriate to a personal action

by Bobby Brunson are striken from the complaint; (2)

That the plaintiff Bobby Brunson shall have twenty days

from the filing of this order in which to file an amended

complaint consistent with the provisions of this order. The

defendants shall have twenty days in which to plead to

such an amended complaint.

Opinion and Order

C. C. W ychb

United States District Judge

(Sitting by Designation)

Dated:

Spartanburg, South Carolina,

May 30,1962.

20a

Notice of Appeal

(Filed: June 21,1962)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe the E astern D istrict of South Carolina

Charleston D ivision

C /A No. 7210

[ same title]

Notice of A ppeal to the United States Court of A ppeals

F or the F ourth Circuit

Notice is hereby given that the plaintiffs in this action

hereby appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit from the Order (1) striking the names

of all the plaintiffs other than Bobby Brunson from the

caption of the complaint and striking from the complaint

all of the allegations inappropriate to a personal action

by Bobby Brunson, and (2) giving the plaintiff Bobby

Brunson twenty (20) days from the filing of said Order in

which to file an amended complaint consistent with the

provisions of said order, signed by the Court on May 30,

1962 and filed herein on May 31, 1962.

Dated: ...... ........ June, 1962.

L incoln C. J enkins, Jr.

Matthew J. Perry

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants