Maxwell v. Bishop Motion for Leave to File and Brief of Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 10, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Bishop Motion for Leave to File and Brief of Amici Curiae, 1969. dbdcfc5c-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3b203ea9-e07f-471b-a350-e6133f2ac217/maxwell-v-bishop-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-of-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

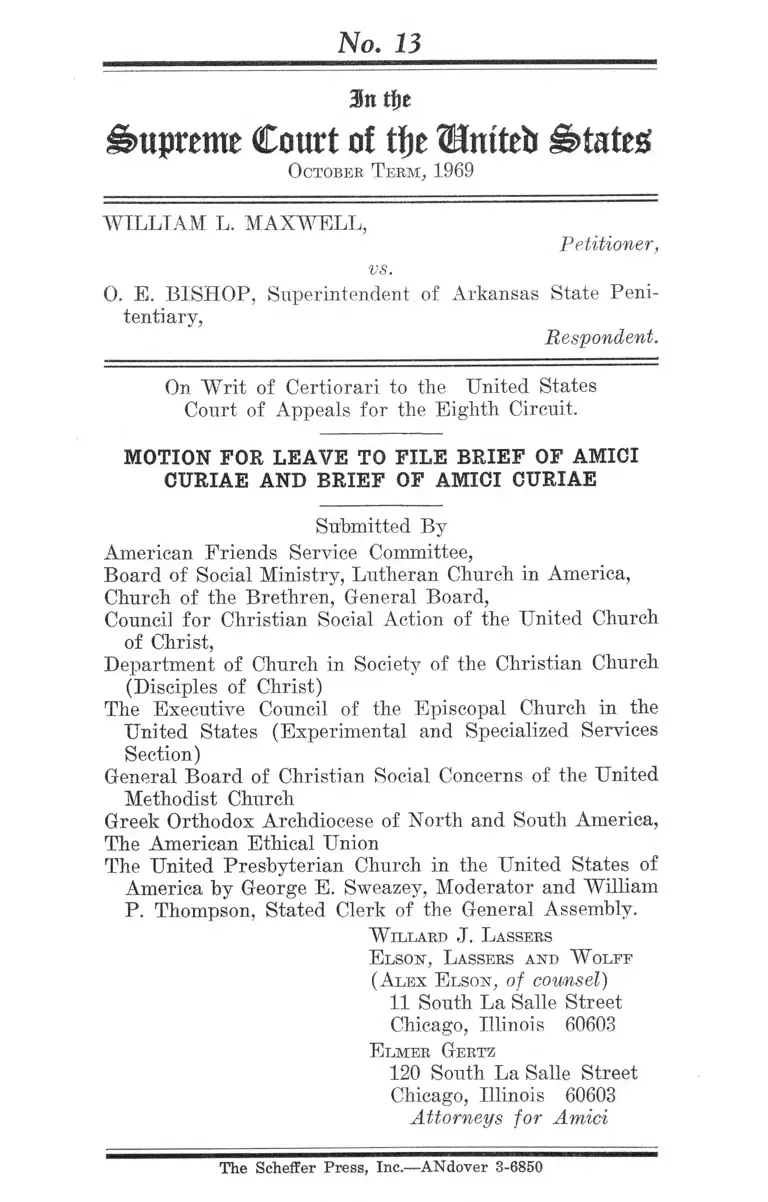

No. 13

in tije

Supreme Court of tfjc States

October T erm, 1969

WILLIAM L. MAXWELL,

Petitioner,

vs.

O. E. BISHOP, Superintendent of Arkansas State Peni

tentiary,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit,

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF AMICI

CURIAE AND BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

Submitted By

American Friends Service Committee,

Board of Social Ministry, Lutheran Church in America,

Church of the Brethren, General Board,

Council for Christian Social Action of the United Church

of Christ,

Department of Church in Society of the Christian Church

(Disciples of Christ)

The Executive Council of the Episcopal Church in the

United States (Experimental and Specialized Services

Section)

General Board of Christian Social Concerns of the United

Methodist Church

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North and South America,

The American Ethical Union

The United Presbyterian Church in the United States of

America by George E. Sweazey, Moderator and William

P. Thompson, Stated Clerk of the General Assembly.

W illard J. L assers

E lsox, L assers and W olff

(A lex E lsox, of coimsel)

11 South La Salle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

E lmer Gertz

120 South La Salle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Attorneys for Amici

The Scheffer Press, Inc.— ANdover 3-6850

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave To File Brief of Amici Curiae ........ 1

Brief of Amici Curiae ..................................................... 9

1. Imposition of the Death Penalty In a Unitary

Trial Is a Deprivation of Life and Liberty With

out Due Process .......... ...... .......................... . 9

Conclusion ................................... —........— ..................... 13

T able of Cases

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 US 510 (1968) .......... ...... 12

In T he

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October T erm., 1969

No. 13

WILLIAM L. MAXWELL,

vs.

Petitioner,

0. E. BISHOP, Superintendent of Arkansas State Peni

tentiary,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF AMICI

CURIAE AND BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

Submitted By

American Friends Service Committee,

Board of Social Ministry, Lutheran Church in America,

Church of the Brethren, General Board,

Council for Christian Social Action of the United Church

of Christ,

Department of Church in Society of the Christian Church

(Disciples of Christ)

The Executive Council of the Episcopal Church in the

United States (Experimental and Specialized Services

Section)

General Board of Christian Social Concerns of the United

Methodist Church

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North and South America,

The American Ethical Union

The United Presbyterian Church in the United States of

America by George E. Sweazey, Moderator and William

P. Thompson, Stated Clerk of the General Assembly.

The above religious organizations by their attorneys,

Willard Lassers and Elson, Lassers and Wolff, (Alex

Elson, of counsel) and Elmer Gertz, move for leave to file

a brief amici curiae in support of petitioner, William L.

Maxwell. In support of this motion the religious organiza

tions represent as follows:

The legal arguments on behalf of petitioner have been

ably presented by his counsel. There are, however, a

number of ethical considerations of deep concern to the

religious organizations. Most of these organizations for

mally have taken stands in opposition to capital punish

ment.1 They are aware that the issue of the death penalty

as such is not at bar.

They desire to present a point of view somewhat differ

ent from that of petitioner, which they think will con

tribute to a more complete understanding of the case.

Hence ask leave to file this brief.

These organizations have a total membership exceeding

34,500,000. They are:

1. AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE.

The Americans Friends Service Committee has, since

1917, engaged in religious, charitable, social, philanthropic

and relief work on behalf of the several branches and

divisions of the Religious Society of Friends in America.

There are approximately 123,000 Friends in the United

States. The American Friends Service Committee, al

1 The statements appear in the appendix to the amicus

brief filed on behalf of the American Friends Service

Committee, et al, in Witherspoon v. Illinois, O.T. 1967,

No. 1015. Substantially every major denomination has

expressed its opposition to the death penalty. The state

ments appear in the Witherspoon brief.

— 3 —

though it cannot speak for all Friends, has a vital interest

in this litigation because of Friends’ historic and con

tinued opposition to the taking- of human life by the

State. Such opposition to capital punishment goes back

more than 300 years, to the beginning of the Quaker

movement and stems from Quaker belief that there is an

element of the divine in every man.

2. BOARD OF SOCIAL MINISTRY, LUTHERAN

CHURCH IN AMERICA

The Board of Social Ministry is an instrumentality of

the Lutheran Church in America. Its object is “ to inquire

into the nature and proper obedience of the church’s

ministry within the structures of social life . . . devoting

itself in particular to those aspects of the church’s min

istry in which individual and social needs are met as an

expression of Christian responsibility for love and jus

tice.”

The 1966 biennial convention of the Lutheran Church in

America adopted a social statement on capital punish

ment encouraging abolition of capital punishment. The

Lutheran Church in America has 3,300,000 members in

6,225 congregations in the United States and Canada.

3. CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN GENERAL

BOARD

The Church of the Brethren General Board is the ad

ministrative arm of the Church of the Brethren. It carries

out policies adopted by the church’s legislative arm—

Annual Conference—in the areas of world ministries,

parish ministries and general services. Among its world

ministries are efforts to correct social injustices at home

and abroad. The Church of the Brethren has adopted

policy statements opposing capital punishment on several

occasions, the last one being in 1959 at the Annual Con

ference. The Church of the Brethren has 200,000 members

in approximately 1,000 churches.

4. COUNCIL FOR CHRISTIAN SOCIAL ACTION

OF THE UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST

The Council for Christan Social Action is an instru

mentality of the United Church of Christ devoted to

promoting education and action in international, political

and economic affairs. The Council stated its position in

opposition to capital punishment in a policy statement of

January 30, 1962. The United Church of Christ has over

10,000,000 adherents.

5. DEPARTMENT OF CHURCH IN SOCIETY OF

THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH (DISCIPLES OF

CHRIST)

The Department of Church in Society of the Division

of Church Life and Work is a part of The United

Christian Missionary Society, a national unit of the

Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). The Christian

Church has approved two resolutions on capital punish

ment in its International Convention. The first resolution,

approved in October 1957 at Cleevland, Ohio, stressed

the need for rehabilitation of criminals and indicated that

“ the practice of capital punishment stands in the way of

more creative, redemptive and responsible treatment of

crime and criminals. The second, “ Concerning Abolition

of Capital Punishment,” was approved in the October

1962 Assembly of the International Convention at Los

Angeles, California. This resolution specifically placed

the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) on record as

— 5 —

“ favoring a program of rehabilitation for criminal of

fenders rather than capital punishment.”

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in the

United States and Canada has a membership of 1,600,648.

6. THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL OF THE EPISCOPAL

CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES (EXPERI

MENTAL AND SPECIALIZED SERVICE SEC

TION)

The Executive Council is the principal administrative

body of The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society

of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States

of America which has 7,546 parishes and missions, 11,362

ordained clergy and 3,588,435 baptized members.

7. GENERAL BOARD OF CHRISTIAN SOCIAL

CONCERNS OF THE UNITED METHODIST

CHURCH

The General Board of Christian Social Concerns is an

instrumentality of the United Methodist Church. Its pur

pose is to further the works of the church in the sphere

of social affairs. The United Methodist Church at its

1960 General Conference adopted a statement opposing

the death penalty. The statement was revised in 1964 and

is now part of United Methodist Social Policy. The United

Methodists number 11,000,000 members among their

38,000 churches which are situated in every state.

8. GREEK ORTHODOX ARCHDIOCESE OF

NORTH AND SOUTH AMERICA.

The Greek Orthodox Church expresses the belief that

every person should be afforded every opportunity to

establish his innocence. If he is found guilty, he should be

— 6 —

afforded every opportunity to present what evidence he can

to mitigate his guilt. The Greek Orthodox Church consists

of 500 parishes, largely in the United States and Canada,

and some in Central and South America. The membership

of the Church is 1,500,000.

9. THE AMERICAN ETHICAL UNION

The American Ethical Union is a federation of the

Ethical Culture Societies and Fellowships in the United

States, which, collectively constitute a liberal religious

humanist fellowship known as the “Ethical Movement”

or the “Ethical Culture Movement.”

The first Ethical Culture Society was founded in New

York City in 1876 by Dr. Felix Adler. There are today

24 Societies and Fellowships of the American Ethical

Union in ten states and the District of Columbia. The

American Ethical Union is a member of the International

Humanist and Ethical Union, a world-wide organization,

with headquarters in Utrecht, The Netherlands. Religious

humanists oppose the death penalty. The American Ethi

cal Union has adopted policy statements calling for its

abolition, and Members and Leaders (Ministers) of Ethi

cal Culture Societies have been active and, in many in

stances, in the forefront of organized efforts to have the

death penalty abolished throughout the United States.

10. THE UNITED PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY

GEORGE E. SWEAZY, MODERATOR AND

WILLIAM P. THOMPSON, STATED CLERK

OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY

The United Presbyterian Church adopted a statement

condemning the death penalty at its 171st general as

— 7 —

sembly in 1959 and adopted a revised statement at the

177th General Assembly in 1965.

The United Presbyterian Church in the United States

of America has a membership of 3,250,000. It has 8,750

churches throughout the nation.

Petitioner has consented to the filing of this brief.

Consent has been requested of respondent, but we have

not yet received a reply.

Respectfully submitted,

W ILLABD J. LASSESS

E lson, L assebs & W olff

( Alex E lson, of counsel)

11 South La Salle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

and

E lmee Geetz

120 South La Salle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Attorneys for Amici.

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

— 9 —

Amici ask this court to hold for petitioner both on the

unitary trial issue and on the lack of standards issue. It

is the unitary trial issue that appears to raise particularly

grave ethical problems, and for that reason these amici

confine their brief to that issue.

I .

Imposition of the Death Penalty In a

Unitary Trial Is a Deprivation of Life

and Liberty Without Due Process

The death penalty is the most awful penalty the law

can impose. Of all murderers, only a few are selected

for the supreme sentence. One would suppose that those

so selected are chosen only after the most searching probe

into every phase of their lives, their character, their

motivation and their personalities. For those who plead

guilty and for those who elect a bench trial, the oppor

tunity for such probe is open. But in most states, for

the defendant who pleads not-guilty, and elects a jury

trial, the door to such probe, realistically, is closed. Be

cause he asserts his innocence, he must yield his oppor

tunity to an effective plea for mercy.

To be sure, the right to present evidence in support of

a plea for mercy and a plea itself is preserved—nominally.

The accused may both argue his innocence and at one and

the same time assert that if his defense is disbelieved, the

jury should spare his life. But such a defense surely is

self-destructive. The jury of laymen scarcely will appre-

10 —

ciate the dilemma of the accused. Hence, the plea for

mercy almost surely will he interpreted as a confession

of guilt. The evidence of innocence disbelieved may influ

ence the jury to impose the ultimate penalty upon an

accused who, they deem, sought to trick them into accept

ing a false tale. The alternative is during the trial to

present nothing, or, at any rate a minimum in support of

a plea for mercy. This course means risking all on the

plea of innocence. Thus the accused is presented with a

cruel dilemma of trial tactics.

But far more is involved than a hard choice of trial

strategy. Moral issues are at stake as well. A defendant

who asserts his innocence may well decline to plead for

mercy, apart from the effect of such plea on his chance

of acquittal. The moral man might well find it wrong to

plead for mercy for a crime he asserts he did not commit,

at least until a judgment of guilt has been passed upon

him. Only at such point, having been judged by a fallible

human judgment, might a man feel free to ask for the

sparing of his life.

For the community, the moral issues are more complex,

more profound. Many defendants, perhaps most, will

elect to make no plea for mercy, preferring to rely on

the plea of innocence. In such case the jury makes its

choice, knowing nothing of the defendant as a. human

being. Yet it is asked to consider the extreme penalty

for him.

This, we think, imposes an immoral task upon the jury,

wholly apart from the issue of the morality of capital

punishment itself.

Since most death sentences are imposed for murder,

let us consider this crime.

11

The Sixth Commandment is “ Thou shalt not kill.” Every

step in the enforcement of this commandment by society is

fraught with the greatest difficulties.

A human being is slain by another. To identify the

killer often is a subtle, baffling task. Often guilt or

innocence as found by a court turns on the question

whether the jury believes one man or another; whether

the rules of evidence permit or exclude one or another

bit of evidence, and similar issues. Having made a

decision that the defendant is responsible for the death,

then the jury has an even more elusive task. Despite the

infinite complexity of human motivation, the crime must

be categorized into one of two or three legislatively de

fined classes, such as “murder”, “voluntary manslaughter” ,

etc.

If the jury chooses the label “murder” , then it must

fix the punishment. Life and death are in its hands. Here,

we think, the religious and ethical teachings of our

Judaic-Christian heritage have special relevance. Only

divine judgments are perfect. God alone can assess

truly the measure of a man’s culpability. The truth of

this ancient teaching has been reaffirmed and reinterpreted

for us by modern learning concerning human motivation.

Yet, by an accident in the development of the law, a man

may be sentenced to death, deprived of an effective oppor

tunity to present evidence in mitigation. The voice of the

accused himself is effectively stilled to plead for his own

life. Even his counsel cannot make a plea for him, or if

he does so, must mute his speech. The jury which dooms

a man may know nothing of him as a man, or as a human

being. His childhood, his youth, his education, his work,

the circumstances leading to the criminal act—-the jury

knows nothing of, except insofar as they are presented

during the guilt-innocence trial. Counsel for petitioner

12

point ont (Pet. Br. 73) that petitioner did not testify.

Hence, “ The jury who sentenced him to die therefore had

heard neither his case for mercy, nor even the sound of

his voice.” Like Joseph K, in Kafka’s The Trial, he is

sentenced without even reasonable opportunity to submit

an initial plea for mercy. Like Joseph K, on the last page

of the novel, petitioner might ask, “Were there arguments

in his favor that had been overlooked?” The procedure at

bar would permit petitioner to perish “ like a dog” . The

“ shame of it” is upon us all.

Such procedure is surely prejudicial to the defendant.

In addition, and this we stress, it compels the jurors to

face an impossible moral dilemma. As jurors they are

sworn to decide between life and death. Yet they are

deprived, where the defendant pleads innocence, from

hearing an effective plea for mercy on his behalf. The

life of a man is in their hands; yet they may know

almost nothing about that man as a human being. How

then can their decision be a moral one? Under the cir

cumstances, it is nearly inevitable that the jury will focus

npon the crime, and pass judgment upon it, when it should

judge the man and pass judgment upon him. This, we

submit, is profoundly wrong.

In Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 US 510 (1968), this

Court held it in error to exclude automatically from the

jury, those who had scruples against the death penalty.

By the inclusion of such persons on the jury, their

moral values, too, come to be reflected in the ultimate

decision. The end sought in Witherpsoon is to bring to

the jury the widest range of public sentiment. But this

more perfectly constituted jury, however, can scarcely

perform its function satisfactorily, indeed morally, if it

is deprived of the fullest knowledge of the man before it.

13

Once the sentence of death is imposed by a jury, the

defendant suffers a prejudice nearly impossible to over

come, even in states such as Illinois where the judge may

overrule the jury. Even if evidence in mitigation is pre

sented to a judge, he often rejects the jury recommenda

tion. Reviewing courts, even where empowered to do so,

are reluctant to overrule a jury or a judge and jury.

The remedy for the evils of the unitary trial is not com

plex. The jury need only decide first the guilt or innocence

of the accused. If it determines guilt, it may then hear evi

dence in aggravation and mitigation and fix or recom

mend the punishment. This procedure is used successfully

in a number of states. An alternative is to empanel a

separate jury solely for the fixing of the penalty. By

either of these methods, the jury, within the limits of

human understanding, can make a rational decision on life

or death. These methods leave to the jury the sentencing

power, but permits its intelligent exercise. Another pos

sibility is to restrict the jury to the guilt-innocence issue,

and to vest sentencing in the judge.

Conclusion

The unitary trial in capital cases unfairly prejudices a

man on trial for his life and thus constitutes a deprivation

of due process of law. It confronts the defendant with a

needless moral question—shall he ask for mercy before

being judged guilty and while asserting his innocence?

It requires the jury to decide the awful question of life

or death when frequently deprived of full knowledge of

the human being before it.

— 14 —

The unitary trial is a bar to an effective plea by a human

being for understanding and for mercy. We plead for

the right to make such a plea. As we show compassion, so

may we receive compassion. In the words of Amos (5:15)

let us “ establish judgment in the gate; it may be that the

Lord God of hosts will be gracious unto” us. In the words

of Mi cab (6:8), let us strive “ to do justly and to love

mercy” . These words of Scripture encompass our plea.

We ask that the judgment be reversed and that this

court find that due process requires the invalidation of

the unitary trial in capital cases.

Respectfully submitted,

W lLLARD J. LASSEBS

E lson, L assebs & W olff

(A lex E lson, of counsel)

11 South La Salle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

and

E lmer Gertz

120 South La Salle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Attorneys for Amici.

September 10, 1969