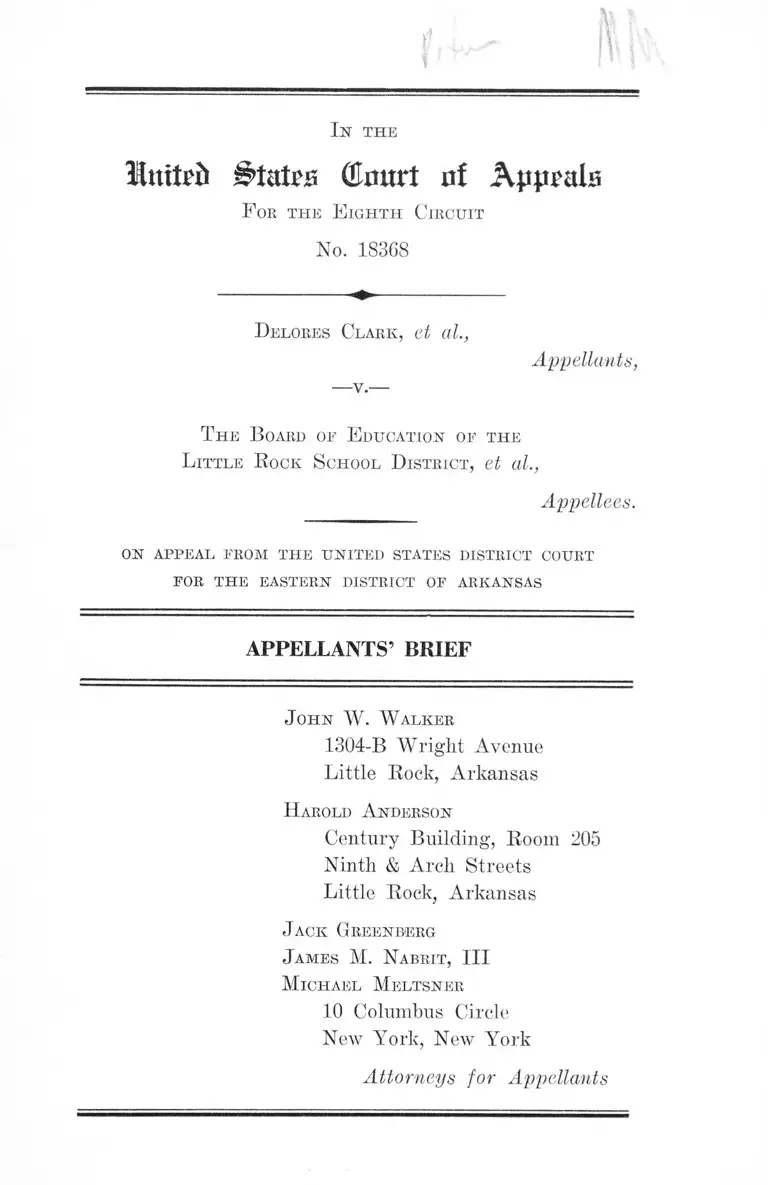

Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Appellants' Brief, 1966. 4aacb69e-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3b9bd5ca-a413-45c7-aa81-729d2a90e10a/clark-v-little-rock-board-of-education-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

United States GJmtrt nf Appeals

F or the E ighth Circuit

No. 18368

D elores Clark, el al.,

-v.-

Appellants,

T he B oard of E ducation of the

L ittle R ock S chool D istrict, et al.,

Appellees.

on appeal from the united states district court

for THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

H arold A nderson

Century Building, Room 205

Ninth & Arch Streets

Little Rock, Arkansas

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of Case .............................. ............................... 1

Statement of Points to Be Argued ................................ 16

A rgument :

I. The Revised “ Preference” Plan Approved

by the District Court Is Both Improper in

This Case and Inadequate to Effect Deseg

regation of the School System ...................... 19

A. Resort to a “ preference” plan is improper

where the board has obtained substantial

delay to implement a geographic zone

Plan .................................... .............................. 19

B. The plan approved is inadequate to de

segregate the Little Rock school system .. 20

II. Appellees’ Policy of Assigning Teachers and

Supervisory Personnel on the Basis of Race

Is Unconstitutionally (a) Vague and Indefi

nite; (b) It Deprives Negro Pupils Who At

tend Negro Schools of Equal Protection; and

(c) Impedes Desegregation Under a “ Pref

erence” Plan by Labelling Schools “ White”

and “ Negro” ..................................................... 25

III. Appellees Are Entitled to an Award of Sub-

stanial Attorneys’ Fees .................................. 32

11

IV. The Court Below Erred in Refusing to Re

tain Jurisdiction of This Cause in Face of

Clear and Convincing Evidence That Tran

sition to a Nonracial System Is Not Complete

and of a Need for Continuing Judicial Super

PAGE

vision of the Desegregation Process ............. 34

V. Conclusion ....................................................... 36

T able of Cases

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E. D. Ark. 1956)

1, 2,6

Aaron v. Cooper, 169 F. Supp. 325 (E. D. Ark. 1959) 12

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957) ....... . 17

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958) ....2, 3,11,13

Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913 (E. D. Ark. 1960)

3,12

Admiral Corp. v. Penco Ins., 108 F. Supp. 1015, aff’d

203 F. 2d 517 (2nd Cir. 1953) .................................... 18, 33

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 ................................18, 29

Beckett v. School Board of Norfolk, Civil Action No.

2144 (E. D. Va.) .........................................................17,27

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321 F. 2d

494 (4th Cir. 1963) ....................... ..................17,18, 22, 32

Bell v. School Board of Staunton, V a .,------F. Supp.

------ (W. D. Va. Jan. 5, 1966) ..................................... 17, 26

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U. S. 103

17, 25, 26, 28

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington, Va., 324

F. 2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) ........................................... 18, 35

I l l

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .......18, 24, 25,

34, 35

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 ...............18, 34

Byrd v. Board of Directors of the Little Rock School

District, Civ. No. LR 65-C-142 ......... .......................... 10

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ..........................................18, 35

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ...........18, 29

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W. D. Okla. 1965) ..........................................17, 26, 31

Gantt v. Clemson College, 320 F. 2d 611 (4th Cir. 1963)

17, 22

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 IT. S. 683 .................. 18, 29

Guardian Trust Co. v. Kansas City So. Ry., 28 F. 2d

283 (8th Cir. 1928) ..................................................... 18,33

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) .....14,16,17,

19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 31

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta, Va., No. 65-

C-5-H (E. D. Va., Jan. 5, 1966) .................... 17, 22, 26, 31

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) ....2, 4, 5, 6,

12,13,18, 32, 35

Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963) ................. 33

Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348 F.

2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965) ..............................................18,31

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U. S. 198 (1965) .......................... 17,25

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line Ry. Co., 186 F. 2d 473

(4th Cir. 1951) ............................................................. 18,33

PAGE

IV

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F. 2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ...............16,17,19, 31

Sprague v. Taconic National Bank, 307 U. S. 161

(1939) ........................................................................... ..18,33

Wright v. County School Board of Greenville County,

------F. Supp.------- (E. D. Va. Jan. 27, 1966) .........17, 26

PAGE

Statutes and R egulations

March, 1966 Revised Statement of Policies Implement

ing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Guide

' s ) ...................................................................20,21,24,29

Other A uthorities

77 Harv. Law Rev. 1135 (1964) ...................................... 33

Statistical Summary of School Segregation-Desegre

gation in Southern and Border States, 15th Revision,

Dec. 1965, Southern Education Reporting Service 28

In the

linxteb i ’tatrii (Emtrt nf Appeals

F or the E ighth Circuit

No. 18368

D elores Clark, et al.,

-v.-

Appellants,

T he B oard of E ducation of the

L ittle R ock School D istrict, et al.,

Appellees.

on appeal from the united states district court

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case*

This appeal is the most recent phase of litigation begun

in 1956 when Negro pupils brought a class action to desegre

gate the public schools of Little Rock, Arkansas. Aaron v.

Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E. D. Ark.). The school district

responded to the suit by proposing a plan for gradual de

segregation to occur over a six year period. The school

* On April 19, 1966, this Court entered an order which stated:

“ . . . appellants may dispense with the preparation of a printed

record and the Court will hear this appeal on the original files of

the District Court and briefs of the parties.”

2

board argued that “gradual” rather than immediate de

segregation was the best transitional plan because of prac

tical problems which were faced by the district in estab

lishment of unilateral geographic attendance areas and con

struction of additional school facilities. Elimination of these

problems, the board argued, would enable the district to

effect an orderly relocation of pupils on an “ attendance

area” basis. At the trial, the board presented maps and

charts which purported to show the expected enrollments

of the school system when operated on the basis of geo

graphic zones.

On the basis of these representations the gradual time

table for the implementation of the plan for desegregat

ing the Little Rock schools (see, Aaron v. Cooper, supra,

aff’d 243 F. 2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957)) provided for high

school integration to begin in 1957; for junior high school

integration “ two or three” years later; and for elemen

tary school integration two or three years after junior

high school integration. System-wise integration of the

Little Rock schools was “ to be completed not later than

1963.” Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798, 801 (8th Cir.,

1961).

Under the plan, nine Negro pupils attended the formerly

all-white Central High School during the 1957 school term

under difficult circumstances. (See, Aaron v. Cooper, 261

F. 2d 97 (8th Cir., 1958).) The schools were closed for the

1958-59 school term during which time the School Board

sought to lease the school facilities to a private school which

would have been racially segregated. This Court, in for

bidding the proposed transfer of facilities, directed the dis

trict court to enter an order enjoining the board “ from en

gaging in any . . . acts . . . which are capable of serving

3

to impede, thwart or frustrate the execution of the integra

tion plan mandated against them” ; and providing for “ such

affirmative steps as the district court may hereafter direct,

to facilitate and accomplish the integration of the Little

Rock School District in accordance with the Court’s prior

orders.” The Court noted further: “ It is of course not the

intention of this provision of our order that appellees

shall take only such affirmative steps to carry out the in

tegration plan as the District Court may expressly direct.

Appellees have an obligation under the previous general

order against them to move forward, within their official

powers, to carry out the integration plan, to which they

must commensurately respond on their own initiative.”

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d at p. 108. These directives were

reiterated in Norwood, v. Tucker, supra.

When the schools were reopened during the 1959-60 school

year, the School Board made school assignments pursuant

to the pupil assignment laws of Arkansas (§§80-1519

through 80-1554, and 80-1234, Ark. Stats., 1947 vol. 7, 1960

replacement). In doing so, the Board allegedly discon

tinued use of “ attendance areas” as the primary criterion

for school assignments. Consequently, many Negro pupils

living within zones of white high schools were assigned

against their choice to the Negro high school located in an

other attendance area. A number of these pupils chal

lenged the deviation from the approved plan and the ap

plication of the assignment criteria. The district court

upheld the board’s deviation from the approved plan and

held that the criteria had been properly applied (Aaron

v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913 (I960)) stating that “ The

Constitution . . . does not require integration. It merely

forbids the use of governmental power to enforce segrega

4

tion” (Id. at p. 931). In reversing the district court, this

Court held that the board must implement its original at

tendance area plan. However, the Court allowed the de

fendants to “ supplement” this original attendance area

plan by a “ proper use” of the placement law. Norwood v.

Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798, 802. However, this Court made the

following observation about the School Board’s applica

tion of the assignment criteria:

It is established without any serious dispute that the

Board’s assignment criteria under the pupil place

ment laws were not applied to any white student in

making these initial assignments; that no white student

was refused assignment to the school of his residence

area or registration; and . . . the evidence convincingly

established that in making initial assignments of plain

tiffs and other Negro students, the Board’s action was

motivated and governed by racial considerations (Id.

at 806).

This Court said further:

. . . we are convinced that Negro students were sub

jected to different treatment in the assignment pro

cedures . . . and that, consciously or otherwise, the

standards and criteria were applied by the defendants

for the purpose of impeding, thwarting and frustrat

ing integration (Id. at 808).

This Court directed the district court to “ retain juris

diction of the cause to the end that our views as herein

expressed are carried into effect.” (Id. at 109).

During the spring of 1964, under a choice plan for grades

one, four, seven and ten, one hundred and eighty-eight

5

Negro pupils made preferences for initial assignment to

predominantly white schools. One hundred and fourteen

were granted. The remaining seventy-four, including one

of the plaintiffs, were refused and assigned to all-Negro

schools. An undetermined number of Negro pupils whose

initial assignment preferences were denied pursued the

administrative remedies of the pupil assignment law.

Twenty-one of the requests were approved. A number were

denied, including the request of plaintiff Ethel Lemar

Moore (Tr. 166, 175).

Shortly before the opening of school in September, 1964,

Negro Army sergeant Roosevelt Clark, moved his family,

which included four school age children, to Little Rock and

sought to enroll his children in the public schools. His wife

inquired by telephone of the school board’s administrative

staff as to which schools their children should attend, and

the staff, apparently acting on the assumption that the

caller was a white person, advised her to enroll in a named

white elementary school and a named white junior high

school located in their general residential area (Tr. 284,

285). However, when Mrs. Clark sought to register her

children in these schools she was refused by the principals

of the two schools and referred to the school board’s ad

ministrative staff. At one of the schools she was advised

that “ they had all the colored children picked out that would

attend the school” (Tr. 285, 286). The administrative staff

assigned the pupils to “ Negro” schools near their home and

relegated them to the administrative remedies of the as

signment law (Tr. 288, 289).

This litigation followed. On September 25, 1964 the

Clark and Moore children moved to intervene in Norwood

v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir., 1961). After a hearing

6

on their motion, the intervention was denied by the district

court on October 26, 1964. The district judge advised the

intervenor applicants at the hearing that a new suit would

have to be filed because of the presence of issues new to the

Aaron and Norwood litigation. The present action followed.

Plaintiffs alleged, inter alia, that: (1) the orders of this

Court directing non-racial use of the pupil assignment

laws were being ignored by defendants; (2) separate schools

for white and Negro pupils were being operated and main

tained and that new construction and site location was

planned on a basis of preserving or continuing segregation;

(3) the district, despite denials, used geographic zoning in

making school assignments based on racially drawn, over

lapping school zones; and (4) faculty and supervisory per

sonnel were assigned on a racial basis.

At the trial of the new action on January 5 and 6, 1965

appellants moved to have this action consolidated with

Aaron v. Cooper, supra; and Norwood v. Tucker, supra. In

denying the motion, the court advised that the orders en

tered in those cases were applicable to this case (Tr. 3, 4, 5).

At the time of trial, there were approximately 23,000

pupils in the school system (Tr. 40) of which 7,341 were

Negro (Tr. 136). Faculties and supervisory personnel were

completely segregated (Tr. 130). Although complete inte

gration was to occur “not later” than September 1963, the

school system was as racially segregated as it was in 1956

with the exception of 212 Negro pupils in formerly white

schools (Tr. 135, 176, 184, 185, 211, 279, 365). (See also,

Answer to Interrogatories, No. 25, dated Jan. 4, 1965.)

Appellees took the position that even though there were

but a token number of Negro pupils in attendance at pre

dominantly white schools, the “preference” procedure fol

7

lowed by the board satisfied its constitutional obligation

(Tr. 169).

The school board encouraged the continuation of segre

gated schools by conducting “ pre-school roundups,” and

junior high and senior high school “ orientation” on a racial

basis and in a way designed to perpetuate racial segrega

tion. New schools were constructed and initially populated

only by Negro pupils and staff (Tr. 211, 212, 273). The

“pre-school roundups” are designed to identify the first

grade population in each school for the coming school year,

to bring the pupils to the schools which they will probably

attend, and to orient the pupils and their parents to the

schools’ physical facilities, teachers and expectations. The

roundups are usually held in the spring before September

school opening. Generally, the principals and teachers of

each elementary school conduct a survey to locate all of

their entering pupils. This is done in several ways. Chil

dren already in attendance are requested to provide the

schools with the names and addresses of relatives and

friends who will be entering the first grade. Parent-Teacher

Association groups make announcements about the round

ups. The result has been that white pupils attend “pre

school roundups” in white schools; Negro pupils in “Negro”

schools. The Deputy Superintendent testified that he did

not know of any Negro pupils who had participated in

“pre-school roundups” in white schools. “Preference”

forms are subsequently distributed to the pupils so that

they may make their choice of schools and pupils are ex

pected to choose the “ roundup” school (Tr. 106, 107, 177,

178, 179). (See also, Answers to Interrogatories Nos. 7, 8,

9, dated Jan. 4,1965.)

8

The board operated “ feeder” elementary schools for

each junior high school. Each elementary school graduating

class was expected to be assigned to a particular junior

high school (Tr. 110, 253, 274). For example, all of the

graduates of Negro elementary schools on the east side of

Little Rock were expected by the School Board and staff

to be assigned to the Negro junior high school on the east

side of Little Rock. Likewise, graduates of “Negro” ele

mentary schools on the west side of Little Rock were ex

pected to “ feed” into the “ Negro” junior high school on

the west side of Little Rock (Tr. 265, 266, 267).

The situation was similar for white pupils. Principals

and counselors from the receiving school visited the

“ feeder” elementary school at a time shortly before the

pupils made their junior high school choices for the purpose

of orienting the pupils to the junior high school programs,

facilities and expectations at their respective schools. Thus,

Negro principals and counselors oriented only Negro pupils

and white principals and counselors oriented only white

pupils (with the exception, of course, of any Negro pupils

in the predominantly white “ feeder” schools graduating

class) (Tr. 107-111). This basic procedure was also fol

lowed in the junior high schools at a time before the grad

uating pupils made their school choices (Tr. 35-39, 107-110,

253, 262, 263, 265, 266, 273, 275).

Assignments of pupils were generally made on the basis

of this feeder school pattern. Ethel LeMar Moore, attended

an all-Negro elementary school. Although she chose a

nearby predominantly white school, she was assigned to

the school which has historically been her elementary

school’s receiving school (Tr. 265). Moreover, the hundreds

9

of pupils, both white and Negro, who made no choice of

schools were assigned to schools solely on a “ feeder school,”

dual attendance area basis (Tr. 31, 34, 83, 100, 107-109,

115, 135, 197, 198, 267, 273, 274, 371). However, those white

pupils who chose schools outside of their “ feeder school”

area or their attendance area were denied their choice

initially by the School Board and after reassignment re

quest. When the Board wanted to grant such choice or

request, they made a “no-but” ruling. The “no-but” policy

simply meant that the Board was denying the choice for the

present but making it possible for the school administrative

staff to grant the requested choice at a later date (Tr. 51, 52,

53, 194-196).

The board’s policy of encouraging segregation is further

seen in (1) the closing of a predominantly white junior

high school shortly before trial, and (2) the closing of an

all-Negro elementary school shortly after trial. The school

board operated a predominantly white junior high school

on the east side of Little Bock until 1964 when it was closed.

The pupil enrollment at that school included more than four

hundred white pupils and twenty-seven Negro pupils (Tr.

21, 29, 30). Shortly before the closing of the east side white

school, the school board opened a new “ Negro” junior high

school on the east side of Little Rock and named it “ after

Bob Booker . . . a respected colored attorney . . . ” (Tr.

236, cf. also 211, 235). Thereupon, the board closed the

east side junior high school and assigned the Negro pupils

in attendance at east side to the Bob Booker school. The

white east side pupils, however, were assigned to the pre

dominantly white west side school located in West Little

Rock. Although representing itself to be operating under a

choice plan, the board made the choice for the pupils strictly

on a racial basis (Tr. 28, 29, 30, 201, 202, 211, 212).

10

The second school closing occurred during the summer of

1965 while the district court was considering the case at

bar. The board closed an all-Negro school which was lo

cated near one existing Negro elementary school and two

predominantly white elementary schools. Simultaneously,

the board opened a new school which was also named for a

distinguished Negro citizen, and staffed it with a Negro

faculty. Pupils were then shifted around by the board on

a geographic attendance area basis. Negro pupils were

reassigned from three different schools by the board in

order to populate the new schools. Significantly, none of the

pupils were assigned to either of the two nearby white

schools although some lived closer to them than to the

Negro schools they were assigned to attend; and none of

the white pupils in the geographic attendance area were

reassigned. Thus, when the district court required the

school board to provide the pupils assigned to Negro

schools an opportunity to make a choice of schools in Byrd

et al. v. Board of Directors of the Little Rock School Dis

trict, Civ. No. LR 65-C-142, the character of the new school

had become an established fact. The board had thus created

by design another “Negro” school and had again made clear

its unwillingness to either assign white pupils to “ Negro”

schools or Negro pupils to predominantly white schools

(ef. Tr. 184,185). (See also Answer to Interrogatories Nos.

28 and 31, supra). However, as a result of Byrd, more than

one hundred of the approximately 1,500 affected Negro

pupils were assigned to the two predominantly white

schools in the general area. This number is reflected in the

district court’s figure of 621 Negro pupils in predominantly

white schools at the beginning of the 1965-66 school term.

11

(See p. 4 of the district court’s opinion of January 14,1966.)

(See also, Tr. 359, 360, 361.1)

Through the 1964 school year, all teachers were hired

on a racial basis—Negro teachers for “Negro” schools;

white teachers for white schools. The Superintendent testi

fied that although the school board had not officially con

sidered desegregating the teaching staffs, the subject pre

sented many problems. One problem he anticipated was

finding white teachers who were willing to teach classes

of all-Negro children (Tr. 338); another was that Negro

teachers probably could not relate properly to white chil

dren (Tr. 339). He presented nothing in support of either

of these beliefs. Although they had no data this position,

the board President and the Superintendent both felt that

Negro teachers were inferior to white teachers and con

sequently, desegregation of the teaching staff should be

delayed (Tr. 45, 46, 339, 340, 341, 352).

This Court in Aaron v. Cooper, 261 P. 2d 97 (1958)

directed the defendants take affirmative action on its own

1 Number of Negro Pupils Attending

White Schools During Desegregation Process

Number of Negro Pupils

School Year in Schools with Whites Source

Prior to Sept. 1957 0____ ------Lower Court opinion

1957- 58

1958- 59 Schools closed

9 of Feb. 4, 1966

1959-60 9 U

1960-61 12 U

1961-62 44 u

1962-63 72 a

1963-64 124 u

1964-65 220 i t

1965-66 471____ ----- Little Rock School

District (7 /19/65)

1965-66 (after Byrd litigation) 621— ------Lower Court opinion

of Feb. 4, 1966

12

initiative to accomplish the objectives of the approved

plan of “ integration.” Aaron v. Cooper, 169 F. Supp. 325,

337 (1959), Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913 (I960) and

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (1961). Testimony ad

duced at trial showed that board members and their school

staff had completely ignored this requirement. In response

to a question from plaintiff’s counsel—“what affirmative

steps has the board taken since May of 1961 to promote

the desegregation of the Little Rock Schools other than

the Board motion which was adopted that you would de-

segregate at a certain school level?,” board President

Matson replied: “ We’ve made no attempt other than that”

(Tr. 49). (See also Tr. 50.) Board member J. H. Cottrell

said that he did not recall “ any affirmative steps taken by

the board pursuant to this Court’s directive” (Tr. 79. 81).

Former Board Member Ted Lamb (whose term expired

shortly before the beginning of this litigation) stated:

I don’t think the Board has taken any affirmative steps

to complete a program of desegregation and eventual

integration of the Little Rock schools. I think they

have only done what they feel is necessary to avoid

contempt of court orders, to avoid being found in con

tempt of court. I don’t think they have done anything

else. All the initiative is on the part of the Negro child

if they want to go into a white school in Little Rock

(Tr. 208, 209).

In addition to the board’s failure to take affirmative steps

to disestablish racial segregation in the schools, the board

members and staff knew little about the plan that the

school system was committed to implement (Tr. 49, 140,

141, 142). The deputy superintendent conceded that he

13

did not know the details of the plan. The Superintendent

stated that he had not made any effort to acquaint himself

“with the so-called Blossom Plan for desegregation” (Tr.

351-352) (cf. p. 242). Appellees did not consider them

selves bound by the initial desegregation plan or by prior

orders in this case. This position was taken by defense

counsel in an oral statement to the court (Tr. 25, 26) al

though prior orders had been issued against the corporate

board, the individual board members, their successors, their

employees, and their attorneys. Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d

97, 108; Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798, 809.

Upon the conclusion of the trial on January 6, 1966, the

district court, the court stated:

. . . the Moore child did everything that was required

under the regulations of the school in her application

for assignment to, I believe it was West Side [junior]

High. As far as the evidence, I find nothing that would

justify the Board’s refusal to permit her transfer. In

fact, I think, in her case, it amounted to a violation—

the refusal amounted to a violation of the Court order

and injunction, so I ’m going to order now the Moore

child admitted to the school which she asked for . . .

at the beginning of the semester, and I want a special

attorney’s fee of $250.00 taxed as costs to her. She

should not have been required to hire counsel to pro

tect her rights. Now, as to the other children, there

is a different question involved and I want to think

about that a few days (Tr. 386).

Subsequently, the “ other” children were reassigned by the

school board to the schools of their original choice thereby

making it unnecessary for the court to take such action.

14

Subsequently, on April 22,1965, before the district court’s

opinion was written, the defendants revised their plan

again. The plan—presented as a Motion and Supplemental

Report—adopted “ freedom of choice” without the restric

tive provisions of the pupil placement law at the first,

seventh and tenth grade levels. Pupils in other grades had

the right to make “ lateral” transfer2 requests which would

not be granted except in “unusual circumstances.” The

board’s teacher desegregation plan was: “ The Board . . .

assumes the responsibility of undertaking and completing

as expeditiously as possible the desegregation of teachers

and staff with the end in view of recruitment and assign

ments without regard to race.”

Defendants implemented their proposed plan, over ob

jections of plaintiffs which were filed May 20, 1965, and

without formal approval of the district court.

On November 26, 1965, the district attempted to conform

its plan to this court’s requirements set out in Kemp v.

Beasley, 352 P. 2d 14 (1965). Thus, all “ entering first

graders, sixth graders going to the seventh grade and ninth

graders going to the tenth grade” were required to make

a choice. Lateral transfers in the other grades would be

granted upon the pupils’ initiative in any case except where

the transfer would cause overcrowding. Notice was to be

given by the classroom teacher.

The district court entered its opinion in this cause on

January 14, 1966, more than one year after trial, and ap

proved the board’s post-trial “abandonment” of the Ar

2 The Board’s definition of “ lateral transfer” was “ the assignment

of a student to a school of the same level (that is elementary, junior

high or senior high) other than the one he currently attends.”

P. 2, letter from Mr. Herschel Friday, Jr. to the District Court

dated November 26, 1965.

15

kansas Pupil Assignment law and the adoption of a

“ choice” plan.

The Court observed that:

Under the proposal those pupils entering the first

grade, the seventh grade (junior high), and the tenth

grade (senior high), as well as all pupils newly en

rolled in the district would be given and even required

to exercise a choice of schools, such choice being ab

solute unless overcrowding would result” (p. 2 of the

district court’s January 14, 1966 opinion).

“As to pupils in the other grades, near the close

of the year they would be reassigned to the same

school. Pupils might apply for reassignment, but it

is a stated policy of the board that such lateral trans

fers would be granted only in unusual circumstances”

(p. 3 of the district court’s January 14, 1966 opinion).

The Court further found that the School Board had com

mitted itself to “ expeditiously” pursuing the problem of

teacher desegregation and had, in fact, assigned four white

teachers to Negro schools and five Negro teachers to pre

dominantly white schools. The court concluded “ that for

the present, at least, no additional order of the Court is

required.”

In giving conditional approval to the “ choice” plan, the

district court required the Board to amend the plan to

include: (1) mid-semester choices for pupils in the twelfth

grade; and (2) annual “ freedom of choice” to be exercised

under reasonable regulations and conditions promulgated

by the board and sufficiently publicized to acquaint all in

terested parties with the simple mechanics of exercising

their right of choice of schools—subject, of course, to the

16

availability of classroom facilities and the overcrowding

of classrooms.

On January 27,1966, the board complied with the Court’s

directive by granting twelfth grade pupils mid-semester

transfers. However, the annual choice requirement was

couched in ‘ -lateral transfer” language and provided: (1)

that if a pupil outside grades one, seven and ten wanted

to transfer to another school he could do so (voluntary

rather than compulsory choice) by obtaining a transfer

form from the office of the school principal or the super

intendent; and (2) notice of “ the annual lateral transfer

right” would be given to the pupils by the classroom

teachers. (Report to the Court dated January 27, 1966.)

The district court entered its order approving the school

board’s plan on February 4, 1966. Notice of appeal was

filed on March 4, 1966.

Statement of Points to Be Argued

I

The Revised “ Preference” Plan Approved by the

District Court Is Improper in This Case and In

adequate to Effect Desegregation of the School

System.

A. Resort to a “preference” plan is improper where

the hoard has obtained substantial delay to im

plement a geographic zone plan.

B. The plan approved is inadequate to desegregate

the Little Rock school system.

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965);

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 355 F. 2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966);

17

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957);

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta, Va.,

No. 65-C-5-H, E. D. Va., January 5, 1966;

Gantt v. Clemson College, 320 F. 2d 611 (4th Cir.

1963);

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321

F. 2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963).

II

Appellees’ Policy of Assigning Teachers and

Supervisory Personnel on the Basis of Pace Is

Unconstitutional in That It (a) Is Vague and

Indefinite, (b) Deprives Negro Pupils Who Attend

Negro Schools of Equal Protection and (c) Im

pedes Desegregation Under a “Preference” Plan

by Labeling Schools “ White” and “ Negro.”

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) ;

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 355 F. 2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966);

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F.

Supp. 971 (W. D. Okla. 1965);

Kier v. County School Board,------F. Supp.------- ,

No. 65-C-5-IJ, E. D. Va., January 5, 1966;

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U. S.

103 (1965);

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U. S. 198 (1965);

Bell v. School Board of Staunton, Va., ------ F.

Supp.------ (W. D. Va. Jan. 5, 1966);

Wright v. County School Board of Greenville

County,------F. Supp.------- (E. D. Va. Jan. 27,

1966);

Beckett v. School Roard of Norfolk, Civil Action

No. 2144 (E. D. V a .);

18

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683;

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399;

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960);

Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348

F. 2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965).

III

Appellees Are Entitled to an Award of

Substantial Attorneys’ Fees.

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321 F.

2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963);

Guardian Trust Co. v. Kansas City So. Ry., 28 F.

2d 283 (8th Cir. 1928);

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line Ry. Co., 186 F. 2d

473 (4th Cir. 1951);

Sprague v. Taconic National Bank, 307 U. S. 161

(1939);

Admiral Corp. v. Penco Ins., 108 F. Supp. 1015,

aff’d 203 F. 2d 517 (2nd Cir. 1953).

IV

The Court Below Erred in Refusing to Retain

Jurisdiction of This Cause in Face of Clear and

Convincing Evidence That Transition to a Non-

racial System Is Not Complete and of a Need for

Continuing Judicial Supervision of the Desegre

gation Process.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349

U. S. 294;

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1;

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961);

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington, Va.,

324 F. 2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963).

19

ARGUMENT

I

The Revised “ Preference” Plan Approved by the

District Court Is Both Improper in This Case and In

adequate to Effect Desegregation of the School System.

A. Resort to a “preference” plan is improper where

the hoard has obtained substantial delay to imple

ment a geographic zone plan.

In Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (Stli Cir. 1957), this

Court approved the Little Rock sis year, geographic at

tendance area, desegregation plan over plaintiff’s objec

tions. The basis for the requested six year delay was to

enable the district to complete its construction program

to provide adequate facilities under a geographic assign

ment plan for the integrated student bodies in the high

and junior high schools. The district has now had nine,

instead of the six years granted by the Court, to complete

its transition. Thus it is highly improper for the board

to propose extending the transition by experimenting with

any kind of a “preference” plan, at best an interim meas

ure, the adequacy of which for desegregation of an urban

school system is doubtful. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, 355 F. 2d 865, 871 (5th Cir. 1966).

Appellants submit that although this Court has given con

ditional approval to “ freedom of choice” as a transitional

desegregation approach because it “ could prove practical

in achieving the goal of a non-segregated system,” Kemp

v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (1965), such principle does not

apply where a board has obtained substantial delay in

order to institute geographic assignment. Despite the

2 0

admonitions of this Court Negro pupils still attend school

in a segregated system. Whatever its validity in other

contexts, Little Rock should not now be permitted to have

the “burden” of making pro-integration school choices

shifted to Negroes. Thus, the court should now squarely

place the burden for desegregating the schools on the

appellees rather than on Negro pupils and require the

board to draw unitary, nonracial zones.

B. The plan approved is inadequate to desegregate the

Little Rock school system.

The plan approved by the district court is a transfer

plan rather than a “ free choice” plan within that term’s

definition in Kemp v. Beasley, supra, and in the Revised

Statement of Policies for School Desegregation Plans

under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (hereafter

referred to as the Guidelines). The plan approved requires

that mandatory choices be exercised only by pupils enter

ing grades one, seven and ten. Pupils entering the other

grades have an annual “ right to express a preference for

reassignment . . . by filing a request for lateral transfer” .

Notice of this right is to be given the students by the

classroom teachers in the various schools.

Both Kemp v. Beasley, supra, and the Guidelines require

all pupils in a choice plan which encompasses twelve grades

to make compulsory annual choices, Kemp v. Beasley,

supra, at pp. 21, 22; the Guidelines, §181.43. A

fatal deficiency of the school board’s plan is that a choice

is neither mandatory, nor annual, in grades other than

one, seven and ten. Failure of any pupil in the system to

make a choice of schools should place the burden upon the

school board to assign the pupil on a nonracial, attendance

21

area, basis. Kemp v. Beasley, supra at p. 22; Guidelines

§181.45. Here, the district, although committed since 1956

to a unitary set of school zone lines, maintains racially

created dual school zones (Tr. 83, 100, 135, 197, 198, 267,

361). The school zone lines must be redrawn or eliminated

altogether if choice is to be acceptable. Kemp v. Beasley,

supra, p. 4.

Moreover, the board’s plan is silent on the period of time

pupils have to exercise their choices. Appellants submit

that the requirements of the Guidelines which provide for

a choice period of not less than 30 days (§181.44), is only a

minimum and that a three month period should be required.

Additionally, the school board’s notice provision—notice

being given by the classroom teachers, and newspaper pub

lication once a week for two consecutive weeks—is far

short of the notice requirements in the Guidelines. They

provide that notice of the plan of desegregation and of

pupils’ right to free choice must be by letter distributed to

each pupil on the first day of the choice period (§181.42).

Additional publication through newspapers, radio and tele

vision is required (§181.53).

Furthermore, the plan is inadequate because:

1. Faculty segregation continues and there is no defi

nite plan for disestablishing the practice;

2. White pupils will not attend Negro schools under the

plan and many schools will remain all Negro;

3. The plan has effected little change of the deliberately

created segregated pattern.

Faculty segregation constitutes a form of encouragement

of segregation which is in violation of the school boards’

22

duty to encourage desegregation. See Gantt v. Clemson

College, 320 F. 2d 611, 613 (4th Cir. 1963); Bell v. School

Board of Powhatan County, 321 F. 2d 494, 499 (4th Cir.

1963). This view was taken by the district court in Kiev v.

County School Board of Augusta, Va., C. A. No. 65-C-5-H,

January 5, 1966. The Court held:

Where, as here, the school authorities have chosen

to adopt a freedom of choice plan which imposes upon

the individual student, to his parent, the duty of choos

ing in the first instance the school which he will attend

(and where the burden of desegregating is imposed

upon the individual Negro student or his parents), it

is essential that the ground rules of the plan be drawn

with meticulous fairness. “ The ideal to which a freedom

of choice plan must ultimately aspire, as well as

any other desegregation plan, is that school boards

will operate ‘schools,’ not ‘Negro schools’ or white

schools.’ ” Brown v. County School Bd., supra, 245 F.

Supp. at 560. See Bradley v. School Bd., supra, 345 F.

2d at 324 (dissenting opinion). Freedom of choice, in

other words, does not mean a choice between a clearly

delineated “ Negro school” (having an all-Negro faculty

and staff) and a “white school” (with all-white faculty

and staff). School authorities who have theretofore

operated dual school systems for Negroes and whites

must assume the duty of eliminating the effects of dual

ism before a freedom of choice plan can be superim

posed upon the pre-existing situation and approved

as a final plan of desegregation. It is not enough to

open the previously all-white schools to Negro students

who desire to go there while all-Negro schools continue

to be maintained as such. Inevitably, Negro children

will be encouraged to remain in “ their school,” built for

Negroes and maintained for Negroes with all-Negro

teachers and administrative personnel. See Bradley

v. School Bd., supra, 345 F. 2d at 324 (dissenting opin

ion). This encouragement may be subtle but it is none

theless discriminatory. The duty rests with the School

Board to overcome the discrimination of the past, and

the long-established image of the “ Negro school” can

be overcome under freedom of choice only by the pres

ence of an integrated faculty.

The school board’s qualified choice plan used throughout

this litigation and the choice plan now in use was adopted

with full knowledge of the fact, and indeed in reliance upon

the fact, that white parents in Little Rock do not choose

to send their children to the all Negro schools as they

are presently constituted (Tr. 28, 29, 31, 34, 68, 71). Thus

the plan, adopted with knowledge of that fact, cannot dis

establish the segregated system. That segregated system

has been meticulously maintained by assignment proce

dures based on the objective of limiting the number of

Negro pupils who would otherwise attend predominantly

white schools and of providing ways for white pupils to

avoid attending “Negro” schools. We urge that a sup

posed remedial effort—a desegregation plan—which re

sults in minimum one-way desegregation should not be ap

proved as adequate.

The experience with a “ preference” approach from 1957

through 1965 demonstrates that it has not effected any sig

nificant reform of the segregation pattern. The statistics

on desegregation in Little Rock (see statement, p. 11,

supra) demonstrates painfully slow change and only mini

24

mal results. We submit that actual results are the only

proper basis upon which to evaluate the adequacy of a de

segregation plan to accomplish the purpose of Brown v.

Board of Education.

Finally, as the school board proposes a freedom of choice

plan which places the burden of desegregation on pupils, the

board should be required to eliminate all other practices

which encourage segregation from the system, e.g., “ pre

school roundups” , and junior and senior high school orienta

tion; the construction and location of schools in neigh

borhoods identifiable as “ Negro” or “white” and the racial

naming of schools.

Unless these safeguards are provided, “ freedom of choice”

cannot under any circumstances be an adequate “ interim”

desegregation plan. More importantly, the adequacy of a

free choice plan cannot be properly determined unless it is

under the district court’s supervision. That court should

require the school board to submit frequent reports on the

progress of desegregation (Guidelines, §181.55); and

should be directed to take such steps as necessary to insure

that within a reasonably short period of time the school

system will be totally “ integrated.”

25

II

Appellees’ Policy of Assigning Teachers and Super

visory Personnel on the Basis of Race Is Unconstitu

tionally (a) Vague and Indefinite, (b) It Deprives Negro

Pupils Who Attend Negro Schools of Equal Protection

and (c) Impedes Desegregation Under a “ Preference”

Plan by Labelling Schools “ White” and “ Negro.”

The school board’s teacher desegregation plan (see State

ment, swpra, p. 14) is unconstitutionally vague and in

definite and fails to protect the rights of Negro school

children. The Board committed itself only to “ expedi

tiously” undertake faculty desegregation “ to the end” that

teacher assignments would be nonracial. It failed to set

forth system-wide standards of assignment or a definite

timetable. The evidence shows that with the exception of

assigning five Negro teachers to “white” schools and four

white teachers to “Negro” schools, the board is continuing

its discriminatory practice of assigning Negro teachers to

“ Negro” schools and assigning white teachers to predomi

nantly white schools. Thus, thirty-five schools have experi

enced no faculty desegregation whatsoever. The failure of

the Board to adopt a definite desegregation plan, or to re

assign a significant number of teachers, renders the plan

approved by the court invalid.3 Rogers v. Paul, 382 U. S.

3 The standing of pupils and parents to question faculty assign

ments was conclusively declared in Bradley v. School Board,

supra, 382 U. S. 103, which holds that removal of race considera

tions from faculty selection and allocation is, as a matter of law,

an inseparable and indispensable command within the abolition of

pupil segregation in public schools as pronounced in Brown v.

Board of Education, supra, 347 U. S. 483. See also Kemp v.

Beasley, supra.

26

198 (1965); Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U. S.

103 (1965); Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965);

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

355 F. 2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966); Kier v. County School Board,

supra; Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F.

Supp. 971 (W. D. Okla. 1965); Bell v. School Board of

Staunton, Va.,------F. Supp.------- (W. D. Va. Jan. 5, 1966);

Wright v. County School Board of Greensville Coimty,

------F. Supp.------- (E. D. Va. Jan. 27, 1966). In view of the

constitutionally required goal of desegregation, it is im

perative that the Little Rock School System be required

promptly to adopt an effective faculty desegregation plan.

Reassignment of an insignificant number of teachers and

absence of a specific, system-wide, plan are plainly unsatis

factory.

In Dowell, supra, the court, adopting the recommenda

tions of educational experts, set a goal of 1970 by which

time there should be “ . . . the same approximate percentage

of nonwhite teachers in each school as there now is in the

system. . . . ” The 1970 date was keyed to personnel turn

over figures indicating that approximately 15% of the total

faculty is replaced each year, and permits the accomplish

ment of a faculty integration by replacements to the faculty

as well as by transfers (244 F. Supp. at 977-78).

In the Kier case, the district court noting the small num

ber of Negro teachers in the system, ordered faculty de

segregation to be completed by the 1966-67 school year and

adopted the Dowell standard:

Insofar as possible, the percentage of Negro teachers

in each school in the system should approximate the

percentage of Negro teachers in the entire system for

the 1965-66 school session.

27

Recently, in Beckett v. School Board of Norfolk, Civ.

No. 2214 (E. D. Ya.) where the faculty is 40% Negro, a

district court entered a consent order on March 17, 1966

approving a plan submitted by the board containing pro

visions for teacher desegregation which in addition to

recognizing its obligation to take all reasonable steps to

eliminate existing racial segregation of faculty that has

resulted from the past operation of a dual school system

based upon race or color, committed the board inter alia,

to the following:

The Superintendent of Schools and his staff will take

affirmative steps to solicit and encourage teachers

presently employed in the System to accept transfers

to schools in which the majority of the faculty mem

bers are of a race different from that of the teacher

to be transferred. Such transfers will be made by the

Superintendent and his staff in all eases in which the

teachers are qualified and suitable, apart from race

or color, for the positions to which they are to be

transferred.

In filling faculty vacancies which occur prior to the

opening of each school year, presently employed teach

ers of the race opposite the race that is in the majority

in the faculty at the school where the vacancy exists

at the time of the vacancy will be preferred in filling

such a vacancy. Any such vacancy will be filled by a

teacher whose race is the same as the race of the ma

jority on the faculty only if no qualified and suitable

teacher of the opposite race is available for transfer

from within the System.

Newly employed teachers will be assigned to schools

without regard to their race or color, provided, that

28

if there is more than one newly employed teacher who

is qualified and suitable for a particular position and

the race of one of these teachers is different from

the race of the majority of the teachers on the faculty

where the vacancy exists, such teachers will be as

signed to the vacancy in preference to one whose race

is the same.4

An effective faculty desegregation plan, as these cases

show, must establish specific system-wide goals to be

achieved by affirmative policies administered with regard

to a definite time schedule. The plan approved by the dis

trict court does not meet these criteria. The Little Rock

school system for valid constitutional and educational rea

sons should be required to submit faculty desegregation

plans patterned after those in the Oklahoma City, Augusta

County, and Norfolk cases.

A total of 13 Little Rock schools have solely Negro

enrollment. No whites attend formerly Negro schools in

Little Rock (Tr. 35, 36). The plan in effect has resulted

in one-way desegregation, i.e., Negro pupils leaving their

all-Negro schools with all-Negro faculties and student

bodies intact.5 It is obvious that if this pattern is continued

without corresponding integration of Negro faculty per

sonnel, not only will meaningful pupil desegregation re

main impossible, but Negro teachers will be gradually

4 A similar plan was approved March 30, 1966, by the district

court in Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, Civ. No.

3353 (B. D. Va.). where about 50% of the teachers are Negro.

5 See comprehensive statistics published by the Southern Educa

tion Reporting Service in its periodic “ Statistical Summary of

School Segregation-Desegregation in Southern and Border States” ,

15th Revision, December 1965, passim.

29

siphoned out of the system, and efforts to achieve faculty

desegregation will no longer be difficult, but impossible.

Faculty segregation impedes the progress of pupil deseg

regation. Where, as here, students and parents are given

a choice of schools it insures schools which are identifiable

on a racial basis and influences a racially-based choice.

Arrangements which work to promote pupil segregation

and hamper desegregation are not to be tolerated in deseg

regation plans. Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683.

Faculty segregation influences a racially-based choice as

surely as the law requiring racial designations on ballots

which was invalidated in Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399.

In Dove v. Parham., 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. I960) this

Court stated the obligation of a school district “ to dis

establish a system of imposed segregation.” Application of

this principle requires an effective, specific faculty and

supervisory personnel desegregation plan not just token

reassignment of a few teachers. The United States Office

of Education has noted the negative consequences of pupil

desegregation without concurrent faculty desegregation.

Thus, in further implementing Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (42 U. S. C. A. 2000d) the Office of Education

in its March, 1966 Revised Statement of .Policies requires

school districts submitting plans for desegregation to com

ply with the following policies.

§181.13 Faculty and Staff.

(a) Desegregation of Staff. The racial composition

of the professional staff of a school system, and of

the schools in the system, must be considered in de

termining whether students are subjected to discrimi

nation in educational programs. Each school system

is responsible for correcting the effects of all past

30

discriminatory practices in the assignment of teachers

and other professional staff.

(b) New Assignments. Eaee, color, or national ori

gin may not be a factor in the hiring or assignment

to schools or within schools of teachers and other

professional staff, including student teachers and staff

serving two or more schools, except to correct the

effects of past discriminatory assignments.

-tf- </■ -Sfe Jfew w w w w

(d) Past Assignments. The pattern of assignment

of teachers and other professional staff among the

various schools of a system may not be such that

schools are identifiable as intended for students of

a particular race, color or national origin, or such

that teachers or other professional staff of a particular-

race are concentrated in those schools where all, or

the majority, of the students are of that race. Each

school system has a positive duty to make staff as

signments and reassignments necessary to eliminate

past discriminatory assignment patterns. Staff de

segregation for the 1966-67 school year must include

significant progress beyond what was accomplished

for the 1965-66 school year in the desegregation of

teachers assigned to schools on a regular full-time

basis. Patterns of staff assignment to initiate staff

desegregation might include, for example: (1) Some

desegregation of professional staff in each school in

the system, (2) the assignment of a significant portion

of the professional staff of each race to particular

schools in the system where their race is a minority

and where special staff training programs are estab

lished to help with the process of staff desegregation,

31

(3) the assignment of a significant portion of the staff

on a desegregated basis to those schools in which the

student body is desegregated, (4) the reassignment of

the staff of schools being closed to other schools in

the system where their race is a minority, or (5) an

alternative pattern of assignment which will make

comparable progress in bringing about staff desegre

gation successfully.

These Office of Education standards for faculty desegre

gation are entitled to great weight. See Kemp v. Beasley,

supra; Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 355 F. 2d 865 (5th Cir. 1965); Price v. Denison

Independent School District Board of Education, 348 F.

2d 1010, 1013 (5th Cir. 1965). Yet the plan approved by

the district court fails to conform in the most elementary

manner to these standards. Significantly, at least two dis

trict courts had fashioned orders before the Office of Ed

ucation adopted its Revised Statement which complement

the new regulations. Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma

City Public Schools, supra, and Kier v. County School

Board of Augusta County, Virginia, supra. Both courts

required plans under which the percentage of Negro

teachers assigned to each school would result in an equal

distribution of Negro teachers throughout the system. This

or similar relief is necessary to eliminate the problem of

faculty segregation in Little Rock. The appellees should

be required to submit a comprehensive and specific admin

istrative plan for complete faculty desegregation in accord

with such definitive guidelines.

32

III

Appellees Are Entitled to an Award of Substantial

Attorneys’ Fees.

In Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321 F. 2d

494, 500 (4th Cir. 1963), the Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit set forth criteria for awarding counsel fees

in school desegregation cases. The criteria included a

board’s: (1) “ refusal to take any initiative” to deseg

regate the schools; (2) “ interposing administrative obsta

cles to thwart the valid wishes of plaintiffs for a deseg

regated education” ; and (3) “ long continued pattern of

evasion and obstruction.” The Bell court concluded that

the “ equitable remedy would be far from complete, and

justice would not be attained if counsel fees were not

awarded in a case so extreme.”

Appellants submit that this case meets the Bell criteria

and is a proper case for the award of substantial counsel

fees by reason of the school board’s refusal to grant the

school choices of Negro children and failure to completely

desegregate the school system. Indeed, litigation has been

required because of the board’s failure to protect the con

stitutional rights of Negro pupils in the Little Eock school

system which should have been desegregated totally no

later than 1963. Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th

Cir. 1961).

The district court made a token award of attorneys’ fees

in the amount of $250.00, but the amount and the limitation

of the award to one plaintiff, was too narrow (Tr. 387).

The expenses and fees were far greater than this nominal

sum. The record shows that the trial itself took two full

days, involved three lawyers, extensive pretrial discovery,

33

post trial memoranda, and numerous conferences. As the

Moore infant should not have been required to obtain coun

sel to protect her rights she was entitled to more than

nominal protection. The Clark infants were, however, re

quired to institute suit in order to secure rights to which

they were plainly entitled and the district court failed to

award them counsel fees, see supra, p. 5. As the school

board brought the entire litigation on itself, both the Clark

and Moore children were entitled to reasonable atorneys'

fees. See Admiral Corp. v. Penco Ins., 106 F. Supp. 1015,

aff’d 203 F. 2d 517 (2nd Cir. 1953).

In a school desegregation suit plaintiffs assert not only

their own rights but those of the class of persons whose

rights the school board is required to protect. This is

necessary in order to protect their individual rights and

also because of the class character of racial discrimination.

In such circumstances named plaintiffs ought not carry

the entire financial burden. Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284

(5th Cir. 1963). The controlling principle is taken from

the class of cases in which the defendant is trustee of a

common fund and as such bound by law to protect the

interests of the plaintiffs who are beneficiaries of the fund.

In such cases where the trust has been violated the courts

do not hesitate to award attorneys’ fees to plaintiffs.

Guardian Trust Co. v. Kansas City So. Ry., 28 F. 2d 283

(8th Cir. 1928); Sprague v. Taconic National Bank, 307

II. S. 161 (1939); Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line Ry. Co..

186 F. 2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951). The public interest in school

desegregation requires no less. See Note, 77 Harv. Law

Rev. 1135 (1964).

In this case, the plaintiffs, of necessity and by the board’s

default, assumed the board’s obligation to protect the con

34

stitutional rights of Negro pupils in Little Rock. Denial of

substantial attorneys’ fees will encourage the school board

to continue the dilatory, evasive, and obstructive tactics

shown by this record (see supra, pp. 7-13) and thereby

encourages further litigation.

IV

The Court Below Erred in Refusing to Retain Juris-

diction of This Case in Face of Clear and Convincing

Evidence That Transition to a Nonracial System Is Not

Complete and of a Need for Continuing Judicial Super

vision of the Desegregation Process.

On February 4, 1966, the District Court entered an order

which stated: “ There being no remaining issues in the

case, the cause is dismissed, at the cost of defendants.”

The district court clearly erred in reaching this conclusion.

First, a number of issues remain, as urged in this brief,

as to which the board has not submitted a constitutionally

valid plan. Under no circumstances, however, should this

case have been dismissed. The Little Rock system is not

completely desegregated— schools still retain their racial

character and are predominantly attended by Negro stu

dents or white students who are instructed by Negro or

white teachers respectively. The board has a continuing

obligation to effect a desegregated system which, as the

history of litigation amply demonstrates, see supra at pp.

1-14, requires judicial supervision.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), 349

U. S. 294 (1955) and its progeny require district courts to

retain jurisdiction over school desegregation cases until

racially segregated school systems are totally eliminated.

35

In its March 2, 1961 opinion this Court clearly directed the

“ District Court . . . to retain jurisdiction of the cause . . . ”

until the segregated system had been replaced by a non-

racial school system, Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d at 809.

While this Court observed in Norwood, supra, that under

the approved desegregation plan, “ integration was to be

effectively completed not later than 1963” that goal has

not yet been achieved by 1966 (italics added). Indeed, the

Deputy Superintendent, Mr. Paul Fair, stated that the

system was still in transition. In response to a question

from appellants’ counsel:

“Well, if you had to come to the court and say to

the Court, ‘Your honor, we think now that the school

desegregation plan is complete and we want to termi

nate this lawsuit, everything is operating as it should

without any racial discrimination,’ do you think we’re

at that stage yet?”—he answered, “ No.”

An instructive decision is Brooks v. County School Board

of Arlington, Va., 324 F. 2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963). There a

district court dissolved an injunction against racial dis

crimination on the ground that the policy of segregation

no longer existed. The Court of Appeals reversed holding

that there was “no long history of sustained obedience”

(Id. at 307) and that district court supervision of transi

tion to a totally desegregated system was contemplated by

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 and Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 FT. S. 1 (Id. at 308). Here there has been no

history of obedience, desegregation is not completed, and

the board’s absence of good faith is demonstrated by its

treatment of the Moore and Clark children (see pp. 5, 13,

supra).

36

CONCLUSION

W herefore appellants respectfully pray that the judg

ment below be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

H arold B. A nderson

Century Building, Room 205

Ninth & Arch Streets

Little Rock, Arkansas

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

< * & » 38