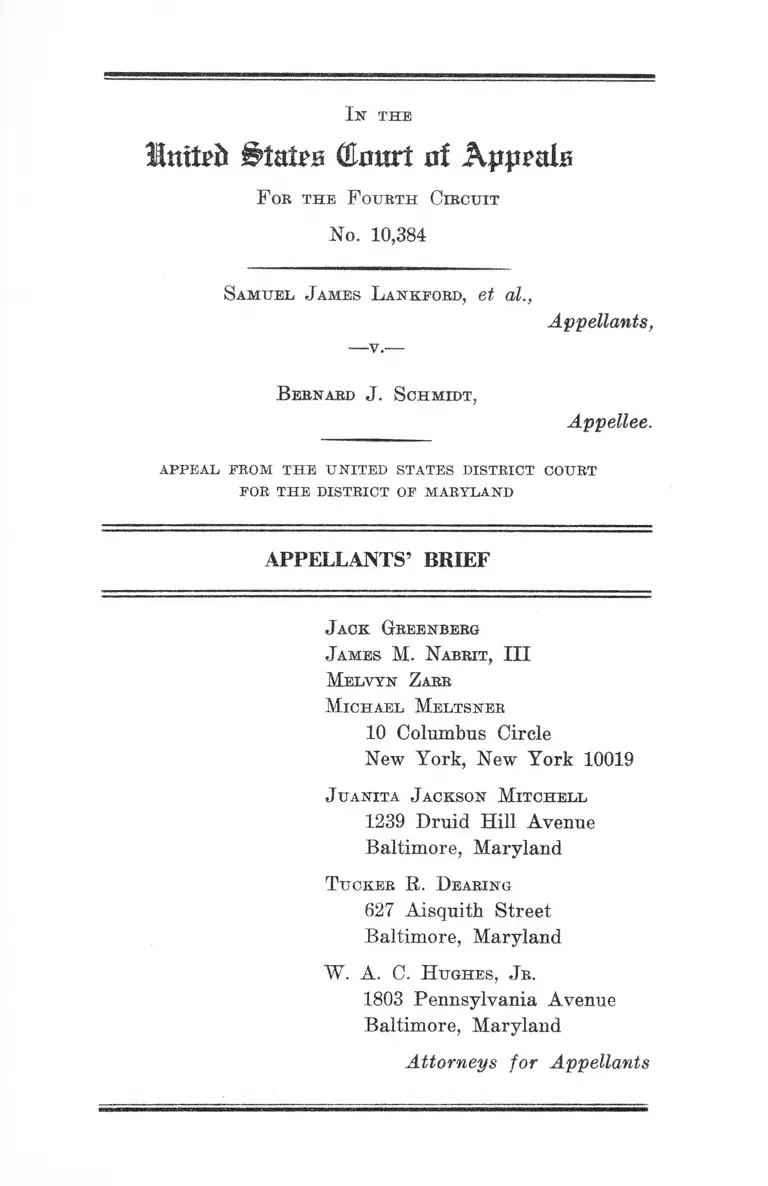

Lankford v. Schmidt Appellant's Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lankford v. Schmidt Appellant's Brief, 1965. 1d69a860-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c231ca2-b84d-4910-bcea-979f4780fdc9/lankford-v-schmidt-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In th e

Intfrfc (Emtrt at Ap£n?alH

F or t h e F ourth Circu it

No. 10,384

S am u e l J am es L ankford , et al..

Appellants,

B ernard J . S ch m id t ,

Appellee.

appeal from th e u nited states district court

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J ack Greenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

M elvyn Z arr

M ich ael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J u an ita J ackson M itch ell

1239 Druid Hill Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

T u cker R. H earing

627 Aisquith Street

Baltimore, Maryland

W . A. C. H u g h es , J r .

1803 Pennsylvania Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ....................................................... 1

Questions Presented .... -........................... ......... -.............. 4

Statement of Facts ............................................................ 4

PAGE

A r g u m e n t ............................................................................................ 1°

I. The Fourth Amendment requires that police o f

ficers obtain search warrants before entering

and searching private premises to attempt to

execute an arrest warrant, in the absence of

consent or exceptional circumstances ............... 18

II. Assuming arguendo that the police are not re

quired to obtain search warrants in the circum

stances discussed in Argument I, the Court

nevertheless erred in refusing to enjoin the

police from continuing the practice of search

ing homes on the basis of anonymous tips and

on mere suspicion ................................................... 45

C onclusion ....................................................................................... 50

T able of C ases

Agnello v. United States, 269 U. S. 20 (1925) ..... ..... 19,25

Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U. S. 108 (1964) ............ ......... -30,46

Alexander v. Hillman, 296 U. S. 222 ............... —- ...... 41

Amos v. United States, 255 U. S. 313 (1921) ............. . 25

Anderson v. Albany, 321 F. 2d 649 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 36

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 ...............................—- 41

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F. 2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963) ....36, 48

11

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 187 .......................................... 36

Bell v. Hood, 327 U. S. 678 (1946) .............................. 35

Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616 (1886) .......21,22,23

Brinegar v. United States, 338 U. S. 160 __________ 38, 40

Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County,

Ya., 332 F. 2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964) ......... ........ ........ 48

Carroll v. United States, 267 U. S. 132 (1925) ______ 25

Chapman v. United States, 365 U. S. 610 (1961) ____ 26

Chappell v. United States, 342 F. 2d 935 (D. C. Cir.

1965) ....... ..................... ............... ....... ......... ................... 31

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d

853 (6th Cir. 1956) ........ ............. ........ ....................... 48

Commonwealth v. Reynolds, 120 Mass. 190, 21 Am.

Rep. 510 (1876) ....... ............. ....................... ............... 32,36

Contee v. United States, 215 F. 2d 324 (D. C. Cir. 1954) 46

Costello v. United States, 298 F. 2d 99 (9th Cir. 1962),

cert. den. 376 U. S. 930 ............................ ........ ......... 46

District of Columbia v. Little, 178 F. 2d 13 (D. C. Cir.

1949), a ffd 339 U. S. 1 (1950) ....... ....................... 29, 31

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965) ____30, 36, 38,

40, 41

Due v. Tallahassee Theatres, Inc., 333 F. 2d 630 (5th

Cir. 1964) _____________ _____ _________ __ ________ 36

PAGE

Egan v. Aurora, 365 U. S. 514 ....... ..... ........ ................ 36

Entickv. Carrington, 19 How. St. Tr. 1029 (1765) ____ 23

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 ....... ...... ............ .......... ........ 44

Frank v. Maryland, 359 U. S. 360 (1959) ...... ...... ......... 22

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, affirming 142 F. Supp.

707 (M. D. Ala. 1956) ................. ......... ..... ................. 36

Giordenello v. United States, 357 U. S. 480 ______ ___ 46

I ll

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U. S. 496 ........................ .............. 36

Henson v. State, 263 Md. 518, 204 A. 2d 516 (1964) .... 35

Henry v. Greenville Airport Comm., 284 F. 2d 631

(4th Cir. 1960) .............................................................. 48

Johnson v. United States, 333 U. S. 10 (1948) ....24,25,31

Jones v. United States, 357 U. S. 493 (1958) ....... 19, 20, 21,

25, 30

Jordan v. Hutcheson, 323 F. 2d 597 (4th Cir. 1963) ....36, 37

Ker v. California, 374 U. S. 23 ........... ....................... 21, 44

Love v. United States, 170 F. 2d 32 (4th Cir. 1948),

cert. den. 336 U. S. 912 (1949) ................................... 32

McDonald v. United States, 335 U. S. 451 (1948) .......24, 25

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 ........... 36

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 (1961) .......20, 21, 37, 38, 41,44

Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U. S. 717 (1961) ........... 22

Martin v. United States, 183 F. 2d 436 (4th Cir. 1950) 32

Miller v. United States, 357 U. S. 301 ..................... ..... 41

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 ........... ...... .............. — 36

Morrison v. United States, 262 F. 2d 449 (D. C. Cir.

1958) ......................... - ............ .................................. 28, 29, 31

Mulcahy v. State, 221 Md. 413, 158 A. 2d 80 ............... 28

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 .................... 41

Nat. Safe Dep. Co. v. Stead, 232 U. S. 58 ............ . 35

Olmstead v. United States, 277 U. S. 438 ......... ........ . 41

Preston v. United States, 376 U. S. 364 (1964) .....— 25

Reeves v. Warden, 226 F. Supp. 953 (D. Md. 1964) .... 28

Rios v. United States, 364 U. S. 253 (1960) ............... 25

PAGE

IV

Sanders v. United States, 373 U. S. 1 __________ __ 44

Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th Cir. 1947) ....... 36

Silverman v. United States, 365 U. S. 505 (1961) ....33,34

Stanford v. Texas, 379 U. S. 476 (1965) ....... ....... 22,23,38

State v. Mooring, 115 N. C. 709, 20 S. E. 182 (1894) ....32, 36

Stoner v. California, 376 U. S. 483 (1964) ....... ......... ..25, 26

Taylor v. United States, 286 U. S. 1 (1932) ................... 25

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ....... ............. ......... 41

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 ............................ ..... 44

United States v. Jeffers, 342 U. S. 48 (1951) ............... 25

United States v. Lefkowitz, 285 U. S. 452 (1932) .......25, 26

United States v. Oregon Medical Society, 343 U. S. 326 48

United States v. Rabinowitz, 339 U. S. 56 (1950) ....... 25, 32

United States v. Rufner, 51 F. 2d 579 (D. Md. 1931) —.46, 48

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S. 629 ...... 48

Wanzer v. State, 202 Md. 601, 97 A. 2d 914 (1953) ...... . 34

Weeks v. United States, 232 U. S. 383 ........................... 44

Wilkes v. Wood, 19 How. St. Tr. 1153 (1763) .............. 23

Williams v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M. D. Ala.

1965) _______ __ __________ ___________ ___ _______ _ 36

W olf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25 (1949) ________ 21, 35, 37, 39

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U. S. 471 .................. 41

Wrightson v. United States, 222 F. 2d 556 (D. C. Cir.

1955) ...... ....... .......................... ........ ........... .................... 46

S tatutes

28 U.S.C.A. §1343 ............. ................ .............. .......... ...... 1

42 U.S.C.A. §1983 ................................ ...... ............ ......... 2,36

PAGE

V

O th er A uthorities

PAGE

A.L.I., Restatement of the Law of Torts, §204 ........... 35

28 Am. Jur., Injunctions, §137........................................... 39

Cooley, Constitutional Limitations (1868) .... .............. 22,33

Hart & Wechsler, The Federal Courts and The Federal

System, 123 (1953) ......................................................... - 48

In the

MuUb (£mtrt ni Appeals

F oe t h e F ourth C ircu it

No. 10,384

S am u e l J ames L ankford , et al.,

-v.-

B ernard J . S c h m id t ,

Appellants,

Appellee.

A PPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E D ISTR IC T OF M A RY LA N D

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This case grows out of the episode known in Baltimore

as “ The Veney Raids”—a prolonged police man-hunt for

two brothers named Samuel and Earl Veney which began

on Christmas day, 1964 and included more than 300 war

rantless and unsuccessful searches of Negro homes in a

19-day period. The plaintiffs in this case (appellants here)

are Negro residents of Baltimore whose homes were

searched during the man-hunt. They filed this class action

January 8, 1965 in the United States District Court for

the District of Maryland seeking an injunction restrain

ing the Police Commissioner of Baltimore and his sub

ordinate police officers from continuing or resuming cer

tain allegedly unconstitutional practices regarding the

searches of private dwellings. The complaint (la-lOa)

alleged jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. A. §1343 as author

2

ized by 42 II. S. C. A. §1983, and asserted that the police

conduct violated the rights of plaintiffs and other Balti

more residents under the Fourth Amendment, enforceable

against the States through the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, and also invaded the equal rights

of plaintiffs and other Negroes in Baltimore to privacy

in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment.

On January 8, 1965, appellants applied to Chief Judge

Thomsen for a Temporary Restraining Order. At a hear

ing in chambers, the Deputy Attorney General of Mary

land, representing the Police Commissioner, orally moved

to dismiss the action, but also promised that the defendant

would issue a general order to his men dealing with the

problems raised by the complaint.1 The Court denied the

motion to dismiss without prejudice, and denied the tempo

rary restraining order in view of the promised general

order, and set the matter for hearing on a preliminary

injunction on January 14. On January 14, a defense mo

tion for judgment on the pleadings was filed (20a) and

denied. An answer was filed (lla-19a) and the taking of

testimony began. Forty-two witnesses testified, and police

records were summarized in a report by a group of special

masters appointed by the Court (185a-186a; 263a; 417a-

419a). The evidence was completed January 27 and there

after the case was fully briefed and orally argued.

An opinion was filed April 14, 1965 (424a-446a; reported

at 240 F. Supp. 550). The opinion contains a lengthy state

ment of facts and discussion of the law. The Court found

that it had jurisdiction as alleged (240 F. Supp. at 555)

and that the appellants had standing to seek relief in a

class action (240 F. Supp. 555-556). The Court rejected

1 General Order No. 10388 was issued January 11, 1965 (18a). It is dis

cussed below in the statement of facts.

3

the appellants’ equal protection claim, finding that the evi

dence failed to show racial discrimination (Id.). The Court

also rejected appellants’ principal Fourth Amendment

argument that except in emergency circumstances the police

are constitutionally required to obtain search warrants

before entering private buildings to search for a person

named in an arrest warrant. The Court held that the police

could enter private buildings without a search warrant to

arrest such a person “ if they have reasonable grounds to

believe that the person is in the building” (240 F. Supp.

558-561).

Appellants’ alternative theory sought an injunction

against searches based on anonymous tips or otherwise

without probable cause. The Court found that most of the

eight searches about which specific testimony was offered

and most of the other 300 or more searches were made

without reasonable grounds to believe the persons sought

to be arrested were on the premises, and rejected the de

fense that the occupants consented to the searches in all

or substantially all cases.2

2 The Court wrote (240 E. Supp. at 557) :

“ Anonymous tips, without something more to support or corroborate

them, do not constitute reasonable grounds. . . . [citations omitted].

Most of the eight turn-ups as to which witnesses testified and most of

the other turn-ups involved in this case were made without reasonable

grounds to believe that the Veneys were on the premises. Most were made

on anonymous tips alone, without any investigation to determine who the

occupants of the house were, or anything else to corroborate them. As a

result the homes of many respectable citizens were subjected to entry by

force under circumstances which were disturbing to children and others

in the house.

Defendant concedes that many entries were made without probable cause,

but contends that the occupants consented in all or substantially all of the

cases. In some instances there was no one there to consent. In others

there was merely acquiescence after at least one officer armed with a shot

gun or submachine gun had already entered the door. Acquiescence under

those circumstances does not constitute consent. Amos v. United States,

255 U. S. 313, 41 S. Ct. 266, 65 L. Ed. 654 (1921).”

4

Notwithstanding the findings and conclusions supporting-

appellants’ alternative theory, the Court declined to grant

injunctive relief. The Court said that such an injunction

would be difficult to frame, difficult to enforce and would

place severe burdens on the police and the Court; that the

Court believed that the Commissioner and other police

officers would make a bona fide effort to observe the rules

stated in the Court’s opinion: and thus the violations were

not likely to be resumed (240 F. Supp. at 561). The pre

liminary injunction was denied, and the Court stated that

“ The case will not be dismissed, but may be called for

trial if it appears necessary.” The order denying relief

was entered May 7, 1965 (447a), and plaintiffs filed a

timely notice of appeal (448a).

Questions Presented

I. Whether the Fourth Amendment requires the police

obtain search warrants naming the place to be searched

before entering and searching private premises to attempt

to execute an arrest warrant for a person reasonably be

lieved to be in the premises, and the Court below erred

in denying injunctive relief against a practice of making

such searches without warrants?

II. Whether, assuming arguendo that the Court below

was correct in its decision of Question I above, the Court

nevertheless erred in refusing to enjoin police from con

tinuing a practice of searching homes on the basis of

anonymous tips and phone calls and from searching homes

on mere suspicion?

Statement of Facts

On the evening of December 24, 1964, a group of men

committed an armed robbery of a liquor store in Baltimore,

during which a police Lieutenant was shot and seriously

5

wounded. One suspect was apprehended immediately, and

the police began searching for several others, including

Samuel Jefferson Veney and his brother Earl Veney. At

about 4 :50 a.m, December 25, police Sgt. Cooper, who was

participating in the search, was found fatally shot near

his cruiser. Warrants were issued that morning for the

arrest of the Veney brothers, who were justifiably believed

by the police to be armed and dangerous.

Early on the morning of December 25th, Commissioner

Schmidt ordered that a special squad be formed to search

for the Veneys under the command of Captain Mahrer of

the Northeast District. The Commissioner gave Mahrer

authority to call as many men or cars as he needed for

the investigation, and the special squad numbered from

50 to 60 men, augmented by additional officers in the vari

ous districts.

Between December 25 and January 12, the Baltimore

police made more than 300 turn-ups in an unsuccessful

effort to locate and arrest the Veneys. A “ turn-up” is an

investigation of a location and usually includes a search

of the premises.3 Most of the searches were at private

3 The special masters’ summary listed 300 searches by dates (419a).

The report indicated that no materials were found with respect to 45 other

incidents contained on a list submitted by defendants (417a). The searches

listed were as follows (419a) :

Date Searches Date Searches

12/24 0 1/3 7

12/25 4 1/4 18

12/26 39 1/5 5

12/27 16 1/6 10

12/28 16 1/7 4

12/29 28 1/8 7

12/30 35 1/9 4

12/31 54 1/10 2

1/1 26 1/11 1

1/2 23 1/12 1

Date Not Shown --1 5

6

dwellings occupied by Negroes. After the first two days,

during which the police concentrated on leads developed

from questioning persons in custody and acquaintances of

the Veneys, “most of the turn-ups were” , the Court found,

“ made as the result of tips, many of them anonymous, as

to the whereabouts of the Veneys, whose pictures and de

scriptions were widely circulated in the press. . . . All tips,

except those which were patently frivolous, were investi

gated, and in most cases resulted in searches of the build

ings” (240 F. Supp. at 553).

The Court found further that:

The police records with respect to many of the

searches are sketchy and incomplete. Frequently all

that is shown is that a particular address was turned-

up on a particular day.

The police did not apply for or obtain search war

rants for the search of any of the more than 300 prem

ises they entered. The decision to enter a house was

usually made by the lieutenant or sergeant in charge

when the tip was received. The entries were made at

all hours of the day and night, usually within 30 or 45

minutes after receiving the tip (240 F. Supp. at 553).

A police emergency vehicle carrying shotguns, sub

machine guns, tear gas apparatus and bullet-proof vests

accompanied the men on every search. Before each turn

up a surveillance team of plainclothesmen would drive past

the building to locate exits, alleyways, etc. but there were

no inquiries in the neighborhoods about the houses to be

searched or other investigations of the anonymous tips,

except that the surveillance team would observe the char

acter of the neighborhood (225a).

Four men carrying shotguns or submachine guns and

wearing bullet proof vests would go to the front door and

knock. They would be accompanied or followed by a ser

7

geant or lieutenant. Other men would surround the house,

training their weapons on windows and doors. “As soon

as an occupant opened the door, the first man would enter

the house to look for any immediate danger, and the super

vising officer would then talk to the person who had an

swered the door. Few stated any objection to the entry;

some were quite willing- to have the premises searched for

the Veneys, while others acquiesced bcause of the show

of force” (240 F. Supp. at 554).4

A number of officers with many years experience on the

Baltimore force made it plain that it was a routine and

normal practice to make searches on the basis of anony

mous tips. The officers in charge of the squad recognized

that they had a problem with false anonymous tips in all

investigations, especially ones with a lot of publicity (355a-

356a; 218-219a; 616a-617a). Lt. Glover of the Homicide

Bureau, a veteran of 18 years on the force, and one of

the leaders of this investigation (207a-208a), led fifty-two

of the searches (220a). He testified that when they re

ceived anonymous calls they evaluated them by listening

to see if the caller “ seemed sincere” and “ sounded authen

tic” ; that they would go out and make turn-ups “if it

sounded like the caller was authentic and they weren’t

very much fast talking and it sounded like they’d like to

talk to you we would call these authentic calls” ; and that

he had used this method of evaluating anonymous calls

during- all his 18 years on the force (218a-219a; 455a-456a).

When only a switchboard operator talked with the anony

mous caller the address would be given to the officers in

charge and they would make searches anyway (223a-226a).

Sgt. William Hughes, who was at times in charge of the

special squad, said that in other cases during his 16 years

4 One officer testified that the practice was for all 4 men with heavy

weapons to enter before the superior officer (273a).

8

on the force they had made searches on the basis of anony

mous calls (278a-279a). Lt. James Cadden, a 16 year vet

eran who was one of the principal officers in charge of the

investigation and participated in 58 searches, testified that

“you had to evaluate the emotions, the emotional voice,

the audibility of the voice calling-” (310a).

Lt. Robert J. Hewes, the night shift commander of the

Northern District ordered the search of the plaintiff Lank

ford’s house after the dispatcher told him he had received

a call that the Veneys were at that address. He testified

as follows (292a-294a):

Q. Did you make any attempt to find out where the

dispatcher—who the dispatcher got the call from !

A. Counsel, it isn’t may job to question the radio dis

patcher, even though I am far and away senior and

so forth and so on, and was the night commander,

night shift commander of the Northern District I am

still more or less under his orders just like I would

be under Lieutenant Cadden’s in a homicide even

though I ’m many years his senior.

Q. So the answer is it wasn’t your job to do it and

you didn’t? A. No, sir. It is my job to carry out the

instructions, period.

The Court: Instructions from whom?

The Witness: From the radio dispatcher.

The Court: Well, that is not quite clear to me

either. I thought you said a moment ago that it

was your decision to make the turn-up and now

you say you were carrying out the instructions of

the radio dispatcher.

I think counsel wants to know, and the Court

wants to know, who was it that made the decision

to make the turn up, was it you on the basis of the

information that had been given you, or was it the

dispatcher or someone over him who made the deci

sion on the information that had been given him?

The Witness: Well, let’s say it this way, having

received the information from the radio dispatcher,

9

who was doing his job, it then became my job to

make the turn-up.

Now, the only one who could stop that turn up

would have been the night inspector who I was

unable to contact; and I am sure he would not have

stopped it.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. You base that last statement on your general

procedure. A. The general procedure of the depart

ment is that whenever you are to do anything out of

the ordinary like that, or there is a serious crime or

anything out of the—injury to an officer or something

like that, you are to inform the night inspector, it is

a courtesy as much as an order. After all, if he is

responsible for the City I figure, you know, it is only

a matter of courtesy.

Q. You say you are sure he wouldn’t have stopped

it because you were acting in accordance with regular

procedure? A. That’s correct, sir.

The Court: What did you understand you were

required to do, when did you understand you were

required to make a turn-up, whenever what?

The Witness: Judge, I am going by twenty four

years experience in the police department. You

ask me why I would feel I was required to make

that turn-up?

The Court: Yes.

The Witness: I would feel I ’d been derelict in

my duty if I hadn’t made the turn up.

The Court: Based on the information you re

ceived?

The Witness: I received information that the

Veney brothers were there and, as I say, I have been

in the department twenty four years and it’s never

been done any different.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. And just to make sure I understand you, you

didn’t check on the dispatcher to find out who he had

1 0

talked to and got this information from? A. He just

said he had received a phone call.

Q. And he didn’t say from whom? A. Actually,

it isn’t his place to have to tell me.

The operating premise of the police was to search any

home where they thought there was a ‘‘possibility” the

Veneys might be.0 Searches on anonymous tips were also

conducted by district officers not connected with the spe

cial squad (340a-341a), and “ scores of homes” were searched

during the earlier “Profili case” where an officer was killed

in a robbery in January 1964 or 1963 (380a).

Lt. Cadden stated that he would do the same thing he

did in this investigation in the future (384a), but after

the Judge indicated surprise at the response (id.) partially

retracted his statement, stating that in the future he would

consult with his Captain and Inspector and be guided by

their decision (385a-387a).

On January 11, shortly after this suit was filed, Commis

sioner Schmidt issued General Order No. 10388 (18a). The

order directs officers to search premises for the purpose

of arresting a person for whom an arrest warrant has

been issued only if the officer has probable cause to believe

the accused is on the premises. I f the officer doubts that

there is probable cause he is directed to either seek a

search warrant or consult with the offices of the State’s

Attorney or Attorney General. There is no direction that

officers seek search warrants where they believe that there

is probable cause. 5

5 Lt. Glover’s testimony at 226a:

Q. Would it be fair to say that your operating premise was that

if there was that you had to cheek out all such places where you

thought you might turn up something? A. Any place where there

was a possibility that the brothers were we were going to turn-up.

1 1

There were only a few searches after issuance of this

order; the last reflected in the record was January 12th.

Also the police stopped getting anonymous tips about the

Veneys at about the same time (189a; 219a; 221a-222a;

Transcript p. 881). The opinion below states that after

January 12 there were only two searches, for each of

which the police obtained search warrants (240 F. Supp.

555), but the record is silent as to this. On March 11, 1965,

Sam and Earl Yeney were arrested by the F. B. I. at a

Long Island, N. Y. factory.

The Court made only general findings with respect to

the events at the eight dwellings with respect to which

testimony was taken. It found that the squads “numbered

between ten and twenty officers and detectives” (240 F.

Supp. at 554) and that some officers were “ polite and con

siderate” while others “were abrupt, and without adequate

explanation of their purpose, flashed lights on beds where

children were sleeping and otherwise upset the occupants

of the home being searched” (id.). With respect to searches

of persons the Court found:

A disabled veteran was patted-down, i.e. checked

for a weapon, after the police had entered his grand

mother’s dwelling, about a block from the corner where

a policeman had been shot at and the badge of his

cap struck by a bullet a few days before. Another

man claimed that he had been patted-down after

another entry, but since he was clad only in his pajama

bottoms, the denial of the officers is more credible

than his claim. When the police raided a pool hall

on Wallbrook Avenue in response to a call from a man

who falsely represented himself as the proprietor and

said that the Veneys were there, the police searched

all patrons of the pool hall for weapons. No other

patting-down is shown by the evidence (240 F. Supp.

at 554).

12

The Court also expressed a general conclusion that most

of the eight searches were made without reasonable

grounds and rejected the police defense that there was

consent for the searches.6

The following are brief summaries of the events relating

to each of the eight homes about which detailed evidence

was adduced:

1. Lankford hom e— 2707 Parkw ood A venue

Mr. and Mrs. Lankford, who have 6 children, have lived

at this address since 1949. Mr. Lankford has worked at

the U. S. Post Office in Baltimore for 10% years (21a; 39a).

Lt. Robert J. Hewes led a search of the house at 2 :00 a.m.

on January 2, 1965. About 45 minutes earlier he had been

told by a communications center officer that he had re

ceived a call that the Yeney brothers were at this address

with a man named Garrett (292a). The Lankfords were

asleep. Mrs. Lankford was awakened by the officers knock

ing on the door and opened the door (22a). The officers

entered the house and began their search while Lt. Hewes

talked with Mrs. Lankford (287a-288a). Lt. Hewes claimed

that Mrs. Lankford gave permission for the search but

acknowledged that his men had already gone to the sec

ond floor while he was talking with her (288a); Mrs. Lank

ford denied that the officers asked for or were given per

mission to search (23a).

Mr. Lankford was awakened in his second floor bedroom

by two flashlights shining in his face and found four men

with shotguns in his room (39a-40a). They questioned him

6 240 F. Supp. at 557; quoted in footnote 2, supra,. See also 240 F.

Supp. at 561: “ The constitutional rights of the plaintiffs of other wit

nesses and of other citizens have been violated by the police on separate

though related occasions.”

13

briefly, while other officers searched the other rooms in

cluding the children’s bedrooms, and left (40a-42a).

2. Tom pkins-Sum m ers-Rayner hom e— 2416 Eutaw Place

This large three-story dwelling is owned by Mr. Claude

Tompkins and his wife, the Rev. Mrs. Elizabeth Tompkins,

a Baptist minister and licensed foster mother who has four

foster children living with her. A third floor apartment is

occupied by the Tompkins’ daughter and her husband and

four children. One second floor room is occupied by Arthur

Rayner, Mrs. Tompkins’ nephew, and another room is

rented to a roomer, James Williams.

At about 11:00 p.m. December 26th, police Sgt. Dunn

found a card in a liquor store check cashing file with the

name Samuel Yeney and the address 2416 Eutaw Place.

The card had a variety of items including Samuel Yeney’s

signature, five inked fingerprints from his right hand, a

driver’s license number; a steel company employee iden

tification number and a physical description. The card

contained the date 6/19, without any year, beside the Eutaw

Place address. Dunn concluded that Veney had cashed a

check on June 19, 1964 and given this address, and immedi

ately reported this to Lt. Manuel. Dunn told Manuel that

the card contained fingerprints but left the card at the

store (353a-360a).

It occurred to Dunn that this might be “ a different Sam

Veney” , but he also thought it might be the person they

were seeking (359a). Actually the Samuel Veney who had

once been a roomer at the Tompkins home was not the

man sought by the police and had left Baltimore and en

tered the Navy in January 1964 (416a). But without any

further investigation Lt. Manuel decided to turn-up 2416

Eutaw Place.

14

Lt. Manuel led a search party which arrived at the house

at 1 :30 a.m. December 27, 1964, and searched the entire

house. There were numerous conflicts in the testimony of

ten witnesses about what happened at the house. Mrs.

Tompkins, Mrs. Summers and Arthur Rayner gave an ac

count depicting a frightening and high-handed type of

armed intrusion by the police, including their pointing

guns at and pushing and shoving Rayner and Mrs. Sum

mers during a search without any request or grant of per

mission. The officers told a different story, denying any

abusive treatment of the occupants and variously claiming

permission to search from all the occupants as well as a

friendly reception culminating in cordial holiday greetings

as they left.

3. Miles hom e— 1140 Shields Place

Mrs. Rita Miles, a hospital employee, lives with her five

children (110a). December 31, 1964 at 12:45 p.m. she

opened the door when policemen knocked and about 7 or 8

officers entered (111a). One told her that they had a tip

that the Veney Brothers were at the house and that her

daughter was “going with one of the Yeney Brothers” (Id.).

Mrs. Miles has a 15 year old daughter in the 9th grade.

Mrs. Miles denied knowing anything about the Veneys and

an officer told her “we got a tip and we have to search the

house” (111a). The officers searched the house and left.

The special masters’ search found records indicating that

this turn-up was made because of an anonymous tip that

the Veneys were seen entering the house (Special Masters’

questionnaire No. 407). The defense offered no evidence

about this search.

4. Hoots hom e— 2303 Allendale Hoad (3 rd floor apartmentJ

Mrs. Terry Boots, a practical nurse lives with her five

children in a third floor apartment in a large detached

15

house. At 4:15 p.m. on December 28, 1964 Mrs. Boots was

in bed and her children were dancing and playing- in the

living room. She heard a knocking on her door and some

one yelling “open up” . Before she reached the door, police

men had opened it and entered. They scattered through

out the apartment searching each room and left without

any explanation of the search. Mrs. Boots’ children were

frightened and crying during and after the search (160a-

163a).

No officers testified about the third floor search. Lt.

Cadden testified that he and several men searched the

first floor apartment finding only several children with

whom he left his calling card (369a). Cadden stated that

the address had been obtained from a friend of the Yeneys

and that there were several phone calls that the Veneys

were being fed at that location (368a). He did not elabo

rate and there was no other evidence as to the reason for

the search.

5. Bond hom e— 917 North Chapel Street

Mrs. Violet Bond and her 14 year old son Frankie have

lived at this address for 10 years. On the morning of De

cember 31, 1964, the house was empty. Frankie was play

ing across the street when the police squad arrived and

officers knocked on the door (167a). Frankie walked over

and told them he lived there; they knocked again and told

him to stand back; he repeated that he lived there and

pushed open the door (167a-168a). The officers testified

that Frankie Bond gave them permission to search; he

denied this.

The search was made because the police learned that

Samuel Veney had given the name of a supposed inhabi

tant of the address as a credit reference for an insurance

policy (365a).

16

6. Floyd hom e— 2204 North R osedale Street

Mr. and Mrs. Floyd were at work (Mr. Floyd is a state

employee) when the police searched their home at 9:00 p.m.

on January 4,1965. Responding to several anonymous calls

(some relayed by a newspaper which had offered a reward

and guaranteed anonymity to informants) that a man re

sembling one of the Veneys had been seen at this address,

the police went to the house (333a). The officers knocked

and called through an open window. IJpon receiving no

answer but hearing noises, they entered the house through

a window and searched it, finding only a dog inside (334a-

335a).

7. Wallace hom e— 2408 H uron Street

Mr. and Mrs. Wallace have lived in this home for 21

years (145a). They live with a 3 year old son, three

daughters, Lucinda (a Baltimore public school teacher),

Harrietta (a college student) and Sharon (a high school

student) and two other relatives.

At 8 :30 p.m. on December 30, 1964, Lt. Coll of the S. W.

district was told by a clerk at another police station that

she received an anonymous call from a man who said that

the Veneys were being sheltered at this address (340a).

Lt. Coll led about 14 officers to the house and searched it

shortly after 9 :00 p.m. When asked why he regarded the

information as sufficiently reliable to act upon the Lieuten

ant answered (346a):

A. Your Honor, due to the fact that this was the first

time that the Police Department had received infor

mation to place the Veneys in this particular area,

I felt it should be investigated.

When the police arrived Lucinda Wallace was showing

slides depicting a summer trip to Hawaii to a group of

her family and guests, including a Bible School group.

17

Mr. and Mrs. Wallace were both out, Mrs. Wallace at a

beauty shop she owned four doors away (82a-84a). While

six officers were searching the house (85a), others sta

tioned outside for a time refused to allow Mrs. Wallace

to enter or explain what was going on (146a). She became

upset and began to cry, and was finally admitted to the

house where she and her daughters all cried (147a). The

police told her that they had received an anonymous call

that the Veney brothers were in the house (147a).

8. Sheppard hom e— 2003 North M onroe Street

Mrs. Maggie Sheppard, 72 years old, has lived at this

address 18 years with her 46 year old grandson, Mr. Roscoe

Cooper, a totally disabled veteran who has suffered from

a mental disorder since 1944 (114a-115a). Cooper is not

permitted to go anywhere by himself, and has not been

out at night since 1944 (123a).

On the morning of January 6, 1965, Mrs. Sheppard went

with her friend Mrs. Florence Snowden, a 72 year old

civic leader, to the Veterans Administration Building to

attempt to get an allotment increase for Cooper (121a;

131a-132a). Upon leaving the V. A. the two ladies rode to

their respective homes in a taxi driven by Mr. Albert

Goodale (298a-299a). Goodale testified that he heard Mrs.

Snowden call Mrs. Sheppard a fool: “Yes, she said you’re

a fool, you don’t know how to take care of business or

something to that effect. And the other lady told her, I

wouldn’t call you a fool. And she said, well, you’re like

your son, she said, he’s a fool, when he gets full of liquor

he shoots a police, and that’s all I heard” (299a-300a). (In

court the ladies denied this account of their conversation).

After discharging Mrs. Sheppard at her house, and

noting the address, Goodale told a policeman what he had

heard. A few minutes later he stopped another police

cruiser and again made the same report (300a-307a).

18

At 11:20 a.m. Sgt. Kelimann got Groodale’s report as

relayed through several officers. He reported this to Lt.

Cadden and they proceeded to the Sheppard home, arriv

ing about noon (313a-316a; 326a-327a). When Mrs. Shep

pard opened the door, several officers entered, seized Cooper

and patted him down and searched the house (319a). When

Mrs. Sheppard would not answer all of the police ques

tions, according to the police account, Mrs. Sheppard and

Cooper were arrested (316a-317a) and taken to the N. W.

district station where they were both booked on the charge

“Investigation, suspected of Assault and Shooting” , and

placed in cells (See arrest register at 420a-422a). They

were detained and Mrs. Sheppard questioned until 2:30

p.m. when Mrs. Snowden and a lawyer arrived at the sta

tion and they were released (317a-319a).

ARGUMENT

I.

The Fourth Amendment requires that police officers

obtain search warrants before entering and searching

private premises to attempt to execute an arrest war

rant, in the absence of consent or exceptional circum

stances.

A.

The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States provides:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons,

houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable

searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no

Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, sup

ported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly de

scribing the place to be searched, and the persons or

things to be seized.

19

The terms of the Amendment prohibit “unreasonable

searches” and do not specify when search warrants must

be obtained. But it is settled doctrine that under the

Amendment a policeman must obtain a warrant “upon

probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and par

ticularly describing the place to be searched” before he

may enter a private place and seize a “thing” . Agnello v.

United States, 269 IT. S. 20, 33; Jones v. United States,

357 U. S. 493, 497. The issue presented by this appeal is

whether an officer must also obtain a warrant “particu

larly describing the place to be searched” before entering

a private home for a search aimed at seizure of a “person” .

The fact that an officer has reasonable grounds to believe

that contraband or other things he may rightfully seize

are in a home does not justify his entry without a warrant

to search for it. But the court below held that a warrant

less search is permissible when an officer reasonably be

lieves a person he has a warrant to arrest is on private

premises.

Appellants submit that there is no rational ground con

sistent with the purposes of the Amendment for such a

rule permitting warrantless entries and searches for per

sons but not for tangible goods. Indeed, the Fourth

Amendment’s terms make no distinction between searches

for persons and things and the Amendment protects the

security of the people in their “persons, homes, papers

and effects” without distinction. Neither the opinion below,

nor any of the decisions it relies on, suggests any ground

for a different rule as to search warrants where the police

man seeks a man rather than his effects.

The United States Supreme Court has never decided the

issue. In 1958 the Court refused to rule on the issue, which

it said was a “grave” constitutional question, on the ground

2 0

that it was not fairly presented on a record which the

Court interpreted as involving a search for goods. Jones

v. United States, 357 U. S. 493, 499-500 (1958). Justices

Clark and Burton dissented arguing that a warrantless

forcible entry was validated by the officers’ reasonable

(but erroneous) belief that a felon they had a right to

arrest was on the premises.

This case presents the issue simply and squarely. The

startling central fact in this litigation is that the Baltimore

police entered and unsuccessfully searched for the Yeneys

in more than 300 buildings in 19 days without ever seeking

or obtaining a warrant naming any of the places searched.

These 300 consecutive mistakes demonstrate the full poten

tial of a rule which leaves the privacy of the home to the

unsupervised judgment of the policeman. Under the defen

dant’s General Order No. 10388, that rule is still in effect,

with the sanction of the court below. The General Order

directs the police to search when they believe they have

probable cause and to seek warrants only if they doubt

they have probable cause.

Appellants seek relief from this rule and from the stark

terror of police state “dragnet” tactics which leave every

man’s dwelling subject to armed invasion on the suspicions

of petty officers at any time of the day or night. The evi

dence demonstrates, with more clarity than any imagined

hypothetical case ever could, the real dangers of such a

rule. It shows again what Mr. Justice Douglas called “the

casual arrogance of those who have the untrammelled

power to invade one’s home” (Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643,

671 (1961), concurring opinion). In this case and under

this rule of law it has been demonstrated that armed and

forcible searches premised on totally uncorroborated anon

ymous tips formed an incredible pattern of invasions of

the constitutional rights of innocent citizens.

21

Appellants urge that their argument is firmly rooted in

the principles of the Fourth Amendment.7 The protection

they seek is not founded upon some novel theory of juris

prudence which a more humane society might incorporate

into its Bill of Bights; rather, appellants seek the very

protection that James Otis and the Framers of the Amend

ment strove to provide, namely, protection against odious

general warrants which sanction wholesale invasions of

private homes and subject the citizenry to a police system

armed with unfettered discretion.

Appellants start with the incontrovertible proposition

that a root policy of the Fourth Amendment is to secure

to the citizen the right of privacy in his home. The land

mark case of Boyd v. United Slates, 116 U. S. 616, 630

(1886), stated the point simply and forcefully:

[The principles of the Fourth Amendment] apply

to all invasions, on the part o f the government and

its employees, of the sanctity of a man’s home and

the privacies of life. It is not the breaking of his

doors and the rummaging of his drawers that consti

tutes the essence of the offense; but it is the invasion

of his indefeasible right of personal security, personal

liberty and private property.8

Appellants agree with the court below that “ [t]he his

tory [of the Fourth Amendment] supports the conclusion

7 The fundamental protections of the Fourth Amendment are guaran

teed by the Fourteenth Amendment against invasion by the States. W olf

v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25, 27 (1949); Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643 (1961);

Ker v. California, 374 U. S. 23, 33 (1963).

8 That the essential purpose of the Fourth Amendment is to protect the

citizen’s right of privacy was reiterated in Jones v. United States, 357

U. S. 493, 498 (1958), per Mr. Justice Harlan:

The decisions of this Court have time and again underscored the

essential purpose of the Fourth Amendment to shield the citizen from

unwarranted intrusions into his privacy.

See, also, W olf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25, 27-29 (1949).

2 2

that the principle attack of the Fourth Amendment

was against general warrants . . . ” (240 F. Supp. at 560).

That the Fourth Amendment was adopted in response to

the abuses which had been committed by governmental

authorities under general warrants has been documented

in decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616, 624-25 (1886); Frank

v. Maryland, 359 U. S. 360, 363-66, 376-77 (1959); Marcus

v. Search Warrant, 367 U. S. 717, 724-29 (1961); Stanford

v. Texas, 379 U. S. 476, 481-84 (1965).

In Boyd, the Court stated (116 U. S. at 624-25):

In order to ascertain the nature of the proceedings

intended by the Fourth Amendment to the Constitu

tion under the terms “unreasonable searches and

seizures,” it is only necessary to recall the contem

porary or then recent history of the controversies on

the subject, both in this country and in England. The

practice had obtained in the Colonies of issuing writs

of assistance to the revenue officers, empowering them,

in their discretion, to search suspected places for

smuggled goods which James Otis pronounced “the

worst instrument of arbitrary power, the most destruc

tive of English liberty and fundamental principles of

law that ever was found in an English lawbook” ; since

they placed “the liberty of every man in the hands of

petty officers.” 9 This was in February 1761 in Boston

and the famous debate in which it occurred was per

haps the most prominent event which inaugurated the

resistance of the colonies to the oppressions of the

Mother Country. “ Then and there,” said John Adams,

“ then and there was the first scene of the first act of

opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great, Britain.

Then and there the child Independence was born.”

These things and the events which took place in

England immediately following the argument about

writs of assistance in Boston were fresh in the mem-

9 Citing Cooley, Constitutional Limitations 301-303 (1868).

23

ones of those who achieved their independence and es

tablished our form of government. . . .10

As every American statesman during our revolu

tionary and formative period as a nation was un

doubtedly familiar with this monument of English

freedom [Entick v. Carrington] and considered it as

the true and ultimate expression of constitutional law,

it may be confidently asserted that its propositions

were in the minds of those who framed the Fourth

Amendment to the Constitution and were considered

as sufficiently explanatory as to what was meant by

unreasonable searches and seizures.

Thus, although the American and English experiences

with general warrants differed in some particulars, the

essential vice of the general warrants was seen to be the

same—the blanket authority given to police officers by a

single warrant to enter and search hundreds of homes,

trampling the right of privacy of their inhabitants in a

dragnet search.

The most recent discussion of the origin and purpose

of the Fourth Amendment is found in Stanford v. Texas,

379 U. S. 476, 481 (1965), which reaffirms the Boyd

analysis:

Vivid in the memory of the newly independent

Americans were those general warrants known as

writs of assistance under which officers of the Crown

had so bedeviled the colonists. The hated writs of as

sistance had given customs officials blanket authority

to search where they pleased for goods imported in

violation of the British tax laws. They were denounced

by James Otis as “ the worst instrument of arbitrary

power, the most destructive of English liberty, and

the fundamental principles of law, that ever was

found in an English lawbook, because they placed

10 The Court then discussed the English landmark eases of Wilkes v.

Wood, 19 How. St. Tr. 1153 (1763), and Entick v. Carrington, 19 How.

St. Tr. 1029 (1765), condemning general warrants.

24

‘the liberty of every man in the hands of every petty

officer.’ ”

The solution adopted by the Framers of the Fourth

Amendment to keep “ the liberty of every man” out of

“ the hands of every petty officer” was the institution of

the search warrant, which interposed the judiciary between

the citizen and arbitrary police power. This rationale of

the search warrant was indelibly recorded by Mr. Justice

Douglas in McDonald v. United States, 335 U. S. 451, 455-

56 (1948):

We are not dealing with formalities. The presence of

a search warrant serves a high function. Absent some

grave emergency, the Fourth Amendment has inter

posed a magistrate between the citizens and the police.

This was done not to shield criminals nor to make

the home a safe haven for illegal activities. It was

done so that an objective mind might weigh the need

to invade that privacy in order to enforce the law.

The right of privacy was deemed too precious to en

trust to the discretion of those whose job is the detec

tion of crime and the arrest of criminals. Power is

a heady thing and history shows that the police acting-

on their own cannot be trusted. So the Constitution

requires a magistrate to pass on the desires of the

police before they violate the privacy of the home. We

cannot be true to that constitutional requirement and

excuse the absence of a search warrant without a show

ing by those who seek exemption from the constitu

tional mandate that exigencies of the situation made

that course imperative.

The institutional preference that determinations of prob

able cause for searches be conducted by disinterested ju

dicial officers rather than by harried police officers was

also articulated in Johnson v. United States, 333 U. S. 10,

13-14 (1948):

not grasped by zealous officers, is not that it denies

The point of the Fourth Amendment, which often is

25

law enforcement the support of the usual inferences

which reasonable men draw from evidence. Its pro

tection consists in requiring that those inferences be

drawn by a neutral and detached magistrate instead

of being judged by the officer engaged in the often

competitive enterprise of ferreting out crime . . .

When the right of privacy must reasonably yield to

the right of search is, as a rule, to be decided by a

judicial officer, not by a policeman or government en

forcement agent.11

Today it is well settled that a search warrant is required

for the search of a private home, subject to established

exceptions.12 Agnello v. United States, 269 IT. S. 20 (1925);

Taylor v. United States, 286 IT. S. 1 (1932); Johnson v.

United States, 333 IT. S. 10 (1948); United States v. Jeffers,

342 IT. S. 48 (1951); Jones v. United States, 357 U. S. 493

(1958); Rios v. United States, 364 IT. S. 253 (1960); Ghap-

11 See also United States V. Lefkowitz, 285 U. S. 452, 464 (1932) :

[T]he informed and deliberate determinations of magistrates em

powered to issue warrants . . . are to be preferred over the hurried

actions of police officers . . . who may happen to make arrests.

Security against unlawful searches is more likely to be attained by

resort to search warrants than by reliance upon the caution and

sagacity of petty officers while acting under the excitement that at

tends the capture of persons accused of crime.

12 The exceptions to the search warrant requirement are: .

1. Search incident to arrest, justified only because of danger to the

officer. See United States v. Rabinowitz, 339 U. S. 56 (1950) ;

Preston v. United States, 376 U. S. 364 (1964).

2. Search of a moving vehicle, justified by its mobility. See Carroll

v. United States, 267 U. S. 132 (1925).

3. Consent (True Waiver, Not Mere Acquiescence). See Johnson v.

United States, 333 U. S. 10, 13 (1948) ; Stoner v. California, 376

U. S. 483 (1964); Amos v. United States, 255 U. S. 313.

4. Perhaps other “ exceptional circumstances.” This exception is rec

ognized by the United States Supreme Court only in dictum. John-

son v. United States, 333 U. S. 10, 15 (1948) ; McDonald v. United

States, 335 U. S. 451, 456 (1948); United States v. Jeffers, 342

U. S. 48, 51 (1951).

26

man v. United States, 365 IT. S. 610 (1961); Stoner v.

California, 376 U. S. 483 (1964).

Appellee contends, and the court below agreed, that

these precedents are all distinguishable because they in

volved searches for things rather than searches for persons

subject to arrest warrants. It is this contention which,

appellants submit, is truly novel and foreign to constitu

tional precepts. There are two major reasons why this

purported distinction cannot be squared with the Fourth

Amendment.

First, the invasion of the privacy of the home of the

citizen is unaffected by the object of the policeman’s

search. When a home owner is subjected to a warrantless

search, it does not assuage his outrage nor lessen the

gravity of the invasion of his privacy to know that the

search is for a suspected felon rather than for some object

of property. The Fourth Amendment protects the citizen’s

right of privacy; an invasion of that right is not eased

by the presentation of an arrest warrant for a stranger.

Second, the Fourth Amendment preference for judicial

rather than police determinations of probable cause for

searches of homes is no less because the intended search

is for persons rather than for things. The requirement of

a search warrant is no mere formality. It reflects the

important Fourth Amendment policy that “ the informed

and deliberate determinations of magistrates empowered

to issue warrants . . . are to be preferred over the hurried

actions of police officers . . . ” (United States v. LefJcowits,

285 IT. S. 452, 464 (1932)). The Fourth Amendment com

mands that judicial officers rather than police officers make

the determination that there exists probable cause for the

search of a particular home. In doing- so, the Fourth

27

Amendment neither makes nor supports a distinction be

tween searches for persons and searches for things.

The opinion below suggests that the existence of an

arrest warrant for a person believed to be within certain

premises somehow obviates the necessity for obtaining a

search warrant. The district court’s opinion founders on

this misconception (240 F. Supp. at 560) :

The privacy of the occupants of the house is, of

course, an important consideration. But it must be

weighed against the interest of all the people that

criminals be arrested and brought to trial, especially

where, as in this case, a warrant has been issued,

based upon the independent judgment of a magistrate,

authorizing the officers to arrest a particular individual.

An arrest warrant embodies a judicial determination that

there exists probable cause for the arrest of the person

named therein, but reflects no judgment at all on the issue

of where the suspect may be found. A magistrate’s deter

mination that there is probable cause to arrest a particular

individual does not satisfy the Fourth Amendment require

ment that a search of particular premises must be based

upon a magistrate’s determination that there is probable

cause to believe that the object of the search is within the

premises to be searched.

No “independent judgment of a magistrate” authorized

the police to enter and search each of 300 homes in their

attempt to find and arrest the Veney brothers! Appellants

submit that an arrest warrant cannot, consistent with the

federal Constitution, become a general warrant authoriz

ing the police to search where they please.

Once it is grasped that an arrest warrant is unrelated to

a judicial determination that an accused is at a given home,

it becomes evident that the issue of the legality of a search

28

is the same whether an officer has an arrest warrant or

otherwise13 has a right to make an arrest.

This point is implicit in the reasoning of Morrison v.

United States, 262 F. 2d 449 (D. C. Cir. 1958), which re

jected the Government’s contention that the Fourth Amend

ment requirement of a search warrant for a home is dis

pensable if the object of the search is to arrest a person

rather than to seize an article of property.

Morrison was convicted of committing a perverted act

on a young boy in his (Morrison’s) home. The evidence

was that the police were notified and were directed to

Morrison’s home. The officers knocked on the front door

and received no response; then one of the officers walked

around to the back of the house, through an opening in

the basement, upstairs, and into the living quarters. He

admitted the other officers and the boy, who pointed out a

handkerchief which he said had been used by Morrison

and which he said bore some tangible evidence of the

offense. This handkerchief was introduced at Morrison’s

trial over his motion to suppress.

The Court of Appeals reversed Morrison’s conviction,

holding illegal the officers’ entry into Morrison’s home.

The Court assumed that the officers had probable cause

to believe both that a felony had been committed and that

the felon was in the house, and that the officers entered

for the sole purpose of finding and arresting the felon.

But the Court rejected the Government’s contention that

the law of arrest, rather than the law of search, governed

the case, saying (262 F. 2d at 452):

13 Maryland law allows a peace officer to arrest without a warrant if he

has reasonable grounds to believe at the time o f the arrest that a felony

has been committed and that the person arrested has committed the offense.

Beeves v. Warden, 226 F. Supp. 953, 957 (D. Md. 1964); Mulcahy v.

State, 221 Md. 413, 421, 158 A. 2d 80.

29

The officers entered the house to make a search. It

was, to be sure, a search for a person rather than the

usual search for an article of property, but it was a

search. The officers made this indubitably clear in

their testimony; they went into the house to look for

Morrison. It is true they intended to arrest him if

they found him, and so the ultimate objective was

an arrest. The Government urges that this latter fact

requires that we apply the rules of law pertaining

to arrest rather than the rules governing search. But

the search was a factual prerequisite to an arrest;

it was the first objective of the entry; the officers

did in fact search the house. They entered to make a

search as a necessary prerequisite to possible arrest.14

Morrison is true to the principles of the Fourth Amend

ment, and is persuasive here. It correctly recognizes that

any relaxation of the search warrant requirement for

searches for persons, as opposed to searches for things,

defeats the essential purpose of the Fourth Amendment

to protect the individual’s right of privacy in his home

by precluding any invasion of that privacy without a judi

cial determination.

Appellants’ position was crystallized in District of Co

lumbia v. Little, 178 F. 2d 13, 17 (D. C. Cir. 1949), aff’d

339 IT. S. 1 (1950):

We emphasize that no matter who the officer is or

what his mission, a government official cannot invade

a private home, unless (1) a magistrate has authorized

him to do so or (2) an immediate major crises in the

performance of duty affords neither time nor oppor

tunity to apply to a magistrate.

14 Compare the faulty analysis of the issue made in State v. Mooring,

discussed infra, Part B, p. 32:

The officer did not justify the breaking on the ground that he had a

search warrant, but a warrant for the arrest of a particular prisoner;

and we are not called upon, therefore, to enter into a discussion of

the constitutional safeguards that protect dwelling houses against

undue search.

30

The rule announced below, which dispenses with warrants

but cautions the officer not to enter without probable cause,

furnishes only illusory protection. As the Baltimore police

keep only “ sketchy and incomplete” records of their

searches and in most cases no records at all (240 F. Supp.

at 553-554), there is no record available which is compara

ble to the sworn statement of facts known to an officer

and asserted to justify his belief that the object of the

search is on the premises, as required to obtain a search

warrant. See Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U. S. 108 (1964).

With no record of the basis for the policeman’s action,

there is little possibility for it to be effectively reviewed

by a court, or even by the policeman’s superior officers.

This rule truly leaves the privacy of every citizen’s home

“in the hands of every petty officer” .

The rule allowing warrantless searches for persons has

an enormous potential for abuse by the police to nullify

the requirement of a warrant to search for goods. The

rule will surely tempt the police (although there is no

record that the Baltimore officers did this) to search for

contraband under the guise of a search for a person.

Jones v. United States, 357 U. S. 493 (1958), involves just

this problem, and the majority and dissenting opinions

illustrate the difficulty courts will have in sorting out the

officers’ motives when they search without warrants nam

ing the place to be searched.

Moreover, the rule does nothing to promote the proba

bility of regularity in the police conduct of searches. By

eliminating the impartial magistrate from the procedure,

the rule facilitates selective and discriminatory disregard

of the probable cause standard, as for example, where the

police think the crime is particularly heinous, or the homes

to be searched belong to less privileged citizens, or to

those who are politically unpopular (cf. Dombrowski v.

31

Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965)). One can accept the finding

of the court below that there was no evidence of racial

discrimination in this case and still legitimately doubt

that the police would have conducted a similar dragnet

in prosperous white residential areas. (See testimony at

225a, and the admonition against class discrimination in

the opinion below at 240 F. Supp. 557-558). Such inva

sions “ could” happen in prosperous suburban developments,

but they did not happen there, nor is it likely that they

will occur on any large scale except to those citizens whom

the police will believe cannot or will not challenge them.

The search warrant rule is not blind to the exigencies

of day-to-day police practice. Exceptional circumstances

or “circumstances of necessitous haste” (Morrison v.

United States, 262 F. 2d 449, 454 (D. C. Cir. 1958)), such

as “hot pursuit” , or actual sight of a felon in the prem

ises, are recognized as justifying failure to obtain a search

warrant. But, mere delay or inconvenience to police of

ficers does not excuse the necessity of obtaining a search

warrant. Johnson v. United States, 333 U. S. 10, 15 (1948);

Chappell v. United States, 342 F. 2d 935, 938-39, footnote

5 (D. C. Cir. 1965), quoting with approval, District of

Columbia v. Little, supra.

B.

No reasoned authority supports a distinction between

searches for persons and searches for things insofar as

the necessity of obtaining a search warrant is concerned.

Appellants concede here, as they conceded below (240

F. Supp. at 558), that they can point to no cases which

explicitly uphold their position and that there are some

cases opposed to their position. But these cases are

faultily, if at all, reasoned, and are unfaithful to the prin

ciples and purposes of the Fourth Amendment.

32

The court below relied in part upon Love v. United

States, 170 F. 2d 32 (4th Cir. 1948), cert, den. 336 U. S.

912 (1949).15 In Love, this Court held that revenue officers

who had an arrest warrant for one Foster could right

fully enter and search Love’s home if they had reasonable

grounds to believe that Foster was in Love’s home. This

Court relied, without discussion,16 on State v. Mooring, 115

N. C. 709, 20 S. E. 182 (1894). Mooring, in turn (as the

court below recognized)17 relied upon Commonwealth v.

Reynolds, 120 Mass. 190, 21 Am. Rep. 510 (1876).

Love’s reliance on Commonwealth v. Reynolds was mis

placed. Commonwealth v. Reynolds held that a police

officer with an arrest warrant who entered the home of

a third person to search for the person named in the arrest

warrant would not be liable for trespass. The court rea

soned as follows (120 Mass, at 196) :

The doctrine that a man’s house is his castle, which

cannot be invaded in the service of process, was al

ways subject to the exception that the liberty or

privilege of the house did not exist against the king.

It had no application, therefore, to the criminal process.

Love’s reliance upon Reynolds was misplaced because

Reynolds’ rationale is fundamentally mistaken: the doctrine

that a man’s house is his castle bore no exception for the

King. The common law of England was stated by Pitt in

his famous Speech on General Warrants:

16 Also cited below was another case in this Court, Martin v. United

States, 183 F. 2d 436 (4th Cir. 1950), but that case is simply inapposite.

In Martin, this Court merely followed United States v. Babinowitz, 339

U. S. 56 (1950) in holding that under the “peculiar circumstances”

(Martin, a probationer, was not arrested, but was notified to appear at

a hearing), the search could be justified as if incident to a lawful arrest

(183 F. 2d at 439).

16170 F. 2d at 33.

17 240 F. Supp. at 558.

33

The poorest man may, in his cottage, bid defiance

to all the forces of the crown. It may be frail; its

roof may shake; the wind may blow through it; the

storm may enter; the rain may enter; but the king

of England may not enter; all his force dares not

cross the threshold of the ruined tenement.18

Thomas Cooley, one of the foremost legal commentators

of the nineteenth century, rehearsed the English and

American origins of the Fourth Amendment and concluded

that the doctrine that a man’s house is his castle not only

bore no exception for the executive but, rather, was ex

pressly designed to curb abuses of executive authority:

The maxim that “ every man’s house is his castle”

is made a part of our constitutional law in the clause

prohibiting unreasonable searches and seizures; and

in the protection it affords, it is worthy of all the

encomiums which have been bestowed upon it.

If in English history we inquire into the original

occasion for these constitutional provisions, we shall

probably find that they had their origin in the abuse

of executive authority, and in the unwarrantable intru

sion of executive agents into the houses and among

the private papers of individuals, in order to obtain

evidence of political or intended political offenses.19

18 Quoted in Cooley, Constitutional Limitations, 299, note 3 (1868).

See also Silverman v. United States, 365 U. S. 505, 511, n. 4 (1961) .

William Pitt’s eloquent description of this right has been often

quoted. The late Judge Jerome Frank made the point in more con

temporary language: “A man can still control a small part of his

environment, his house; he can retreat thence from outsiders, secure

in the knowledge that they cannot get at him without disobeying the

Constitution. That is still a sizable hunk of liberty-worth protecting

from encroachment. A sane, decent, civilized society must provide

some such oasis, some shelter from public scrutiny, some insulated

enclosure, some enclave, some inviolate place which is a man’s castle.”

United States v. On Lee (C. A. 2 N. Y .), 193 F. 2d 306, 315, 316

(dissenting opinion).

19 Cooley, Constitutional Limitations, 299-300 (1868).

34

This truth was reinterated as recently as 1961 in a de

cision of the United States Supreme Court:

The Fourth Amendment, and the personal rights

which it secures, have a long history. At the very

core stands the right of a man to retreat into his own

home and there be free from unreasonable govern

mental intrusion. Entick v. Carrington, 19 Howell’s

State Trials, 1029, 1066; Boyd v. United States, 116

U. S. 616, 626-630, 29 L. ed 746, 749-751 6, S. Ct 524.20

The court below also relied upon decisions of the State

of Maryland, citing Warner v. State, 202 Md. 601 at 609,

97 A. 2d 914 at 917 (1953) and quoting therefrom Chief

Judge Sobeloff’s statement: “ Entry on private premises

to execute an arrest warrant is legal.” Neither the hold

ing of, or the quotation from, Warner supports the deci

sion below. In Warner, a state trooper, responding to a

complaint at 3:00 a.m. from a neighbor that loud noises

were emanating from Wanzer’s property, went there to

investigate. When the trooper approached within 100 yards

of the residence, he observed through a picket fence 40 to

50 people milling about on Wanzer’s lawn, some holding

cans of beer, and heard loud dance music and laughter.

Accompanied by a neighbor, the trooper entered the front

gate and started arresting those on the property for al

leged disturbance of the peace. The Court of Appeals of

Maryland held that the entry on Wanzer’s property was

illegal, and reversed Wanzer’s conviction. The court stated

(97 A. 2d at 917):

Apart from consent, does the law permit entry by

officers, without a warrant, upon private property

under such facts as this case presents! . . . Entry on

private premises to execute an arrest warrant is legal.

Hubbard v. State, 195 Md. 103, 72 A. 2d 733.21 The

20 Silverman v. United States, 365 U. S. 505, 511 (1961).

21 In Hubbard, the court merely found that, under the circumstances

presented, there had been a valid waiver o f a search warrant.

35

precise question of the legality of entry without a war

rant turns on whether the events seen and heard by

the officers constituted the commission of a [breach of

the peace] in their presence.

The court then proceeded to hold that there existed in

sufficient evidence of a breach of the peace to justify the

officers’ entry.

Thus the statement from Warner quoted by the court

below is not only purest dictum, but is unsupported as

well.

Also inapposite, although cited by the court below, is

Henson v. State, 263 Md. 518, 204 A. 2d 516 (1964), which

held that officers who possess a valid search warrant for

a house may, under exigent circumstances, forcibly break

and enter the house without prior demand to enter.

The court below also relied upon §204 of the Restate

ment of the Law of Torts. That section merely provides

that a person privileged to make an arrest is not liable

in trespass to a possessor of land for an entry on the

land for the purpose of making an arrest, if the person

sought to be arrested is on the land or if the person privi

leged to make the arrest reasonably believes him to be

there. But merely because a possessor of land does not

have a cause of action under state law does not govern

the question of whether he has a federal cause of action.

Cf. Bell v. Hood, 327 U. S. 678 (1946). When the Restate