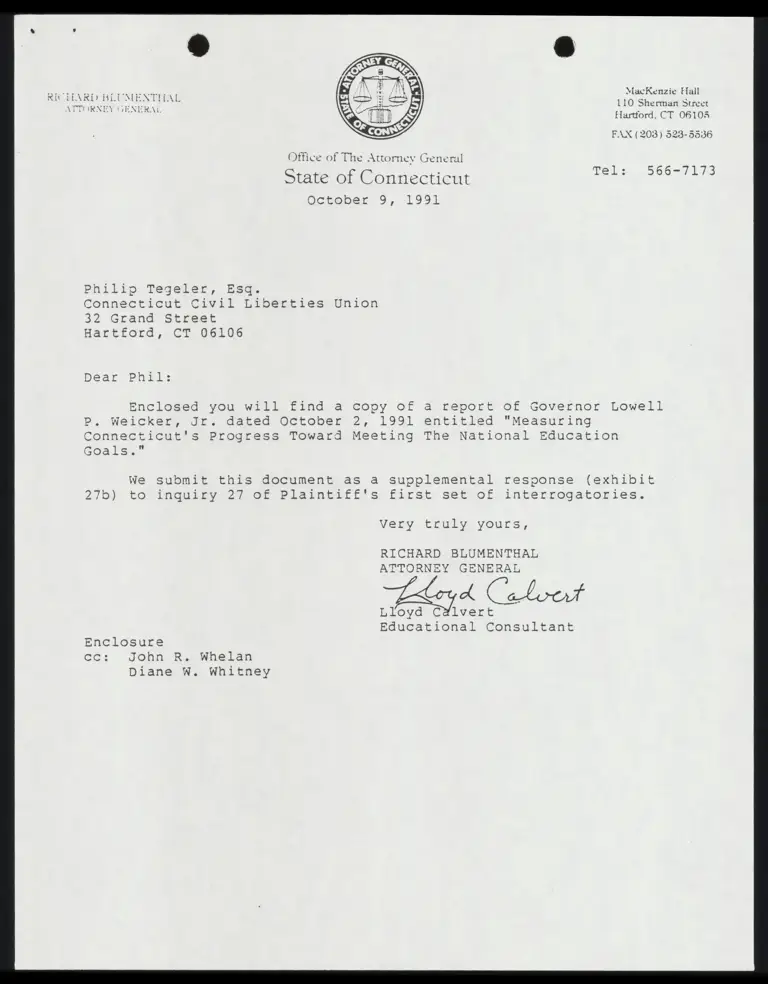

Correspondence from Calvert to Tegeler with "Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward Meeting the National Education Goals" Report

Reports

October 9, 1991

48 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Correspondence from Calvert to Tegeler with "Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward Meeting the National Education Goals" Report, 1991. 7970f639-a446-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c6de01e-fc3d-422b-89c1-85056f23891b/correspondence-from-calvert-to-tegeler-with-measuring-connecticuts-progress-toward-meeting-the-national-education-goals-report. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

i

MacKenzie Hall

110 Sherman Strect

Hartford, CT 061053

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL

ATTORNEY GENERA,

FAX (203) 523-5536

Office of The Attorney General

State of Connecticut

October 3, 1931

Tel: 566-7173

Philip Tegeler, Esq.

Connecticut Civil Liberties Union

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 0610s

Dear Phil:

Enclosed you will find a copy of a report of Governor Lowell

P. Weicker, Jr. dated October 2, 1991 entitled "Measuring

Connecticut's Progress Toward Meeting The National Education

Goals."

We submit this document as a supplemental response (exhibit

27h) to inquiry 27 of Plaintiff's first set of interrogatories.

Very truly yours,

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL

ATTORNEY GENERAL

L Colorent

Lloyd Cdlvert

Educational Consultant

Enclosure

df John R. Whelan

Diane W. Whitney

Report of the Governor

Measuring Connecticut's Progress

Toward Meeting

The National Education Goals

Governor Lowell P. Weicker, Jr.

October 2, 1991

LOWELL P. WEICKER JR.

GOVERNOR

STATE OF CONNECTICUT

EXECLTIVE CHAMBERS

HARTFORD. CONNECTICUT

06106

October 2, 1991

Dear Friends:

At the 1989 Education Summit in Charlottesville, President Bush and the country's

governors comrmutted themselves to six national education goals to be realized by the

year 2000.

The first report of the National Educatdon Goals Panel was released on September 30

with a first look at the problems found and the progress made.

Connecticut's first report looks at some of the same problems and deals with educa-

tional, demographic and social conditions affecting its students, young and old.

[ urge you to read this report carefully and to be ready to cooperate with other con-

cerned citizens to build upon our successes and tackle the challenges that lie ahead. I

recommend to you Measuring Connecticut's Progrexs Toward Meering the National

Education Goals.

Governor

Contents

Acknowledgments

National Education Goals and Objectives

Introduction

Critical Links in Accountability

The Before School Years

The School Years

The After School Years

Summary

Appendix — Comparison of the State Board

of Education's 1991-1995

Comprehensive Plan Goals and

The National Education Goals

33

36

Acknowledgments

Many individuals have contributed ty the development of this report. Thanks are due to the Connecticut Departments of Educa- tion, Higher Education, Health Services, Human Resources, Children and Youth Services, Labor, Mental Retardation, and Income Maintenance, as well as to the Connecticut State Library, the Commission on Children, the Connecticut Employment and Training Commission and the Connecticut Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission.

In addition, statewide businesses, labor organizations, profes- sional organizations and legislators also have provided valuable contributions.

Specialthanks go out to Wanda Dupuy (Office of Policy and Man- agement), Kathy Frega (Department of Education), Valerie Lewis (Department of Higher Education), Emily Melendez (Governor's Office) and Betty Schmitt (Department of Education), whose guid- ance and perseverance were invaluable in compiling this report. Thanks to Marsha Howland and Betty Speno (Department of Edu- cation) for their time and expertise in publishing this report.

Meeting The National Education Goals

—@ heportofthe Governor —@—o-—__

Readiness

Goal 1

By the y=2r 2000, sl! children in Amer-

ica will start school ready to learn.

Objectives

All disadvantaged and disabled children

wilt have access to high-quality and devel-

opmentally appropriate preschool pro-

gramsthat help prepare children for school.

Ev2y parent in America will be a child's

first teacher and devote time each day

helping his cr her preschool child learn;

parents will have access to the training

and support they need.

Children will receive the nutrition and heath

care needed to arrive at school with healthy

minds and bodies, and the number of low-

birth-weight babies will be significantly

reducedthrough enhanced prenatal health

systems.

High School Completion

Goal 2

By the year 2000, the high school gradu-

ation rate will increase to at least 90

percent.

Objectives

The nation must dramatically reduce its |

dropout rate, and 75 percent of those stu-

dents who do drop out will successfully

complete a high school degree or fits

equivalent.

The gap in high school graduation rates |

between American students from minority

backgrounds and their nonminority

counterparts will be eliminated.

Student Achievement

and Citizenship

Goal 3

By the year 2000, American students

will leave grades four, eight and twelve

having demonstrated competency over

challenging subject matter including

English, mathematics, science, history

and geography; and every school in

America will ensure that all students

learn to use their minds well, so they

may be prepared for responsible citi-

Zzenship, further learning, and produc-

tive employment In our modern econ- |

omy.

1v

| {

|

Objectives

The academic performance of slemen-

tary and secondary students will increase

significantly in every quartile, and the

distribution of minority students in each

level will more closely reflect the student

population as a whole.

The percentage of students who demon-

strate the ability to reason, solve prob-

lems, apply knowledge, and write and

communicate effectively will increase

substantially.

All students will be involved in activities

that promote and demonstrate good citi-

zenship, community service and personal

responsibility.

The percentage of students who are

competent in more than one language will

substantially increass.

All students will be knowledgeable about

the diverse cultural heritage of this nation

and about the world community.

Mathematics and Science

Goal 4

By the year 2000, U.S. students will be

first in the world in mathematics and |

sclence achievement.

Objectives

Math and science education will be

strengthened throughout the system,

especially in the early grades.

The number of teachers with a substan-

tive background in mathematics and sci-

ence will increase by 50 percent.

The number of U.S. undergraduate and

graduate students, especially women and

minorities, who complete degrees in

mathematics, science and engineering will |

increase significantly.

Adult Literacy and

Lifelong Learning

Goal 5

By the year 2000, every adult American

will be literate and will possess the

knowledge and skills necessary to |

compete in a global economy and

exercise the rights and responsiblii-

ties of citizenship.

Nat@nal Education Goals and Objectifs

Objectives

Every major American business will be

involved in strengthening the connection

between education and work,

All workers will have the opportunity to

acquire the knowledge and skills, from

basic to highly technical, needed to adapt

to emerging new technologies, work maeth-

ods, and markets through public and pri-

vate educational, vocational, technical,

workplace or other programs.

The number of quality programs, includ-

ing those at libraries, that are designed to

serve more effectively the needs of the

growing number of part-time and mid-

career students will increase substan-

tially.

The proportion of those qualified students,

especially minorities, who enter college,

who complete at least two years, and who

complete their degree programs will in-

crease substantially.

The proportion of college graduates who

demonstrate an advanced ability to think

critically, communicate effectively and

solve problems will increase substan-

tially.

Safe, Disciplined and

Drug-Free Schools

Goal 6

By the year 2000, every school In

America will be free of drugs and vio-

lence and will offer a disciplined envi-

ronment conducive to learning.

Objectives

Every school will implement a firm and fair

policy on use, possession and distribution

of drugs and alcohol.

Parents, businesses and community or-

ganizations will work together to ensure

that schools are a safe haven for all chil-

dren.

Every school district will develop a com-

prehensive K-12 drug and alcoho! pre-

vention education program. Drug and

alcohol curriculum should be taught as an

integral part of heatth education. In addi-

tion, community-based teams should be

organized to provide students and teach-

ers with needed support.

—@— Report of the Governor —@—o—

Introduction

The National Governors Association, in a policy adopted in July

1990, called upon each governorto issue a report to mark his or her

state's progress toward reaching the six National Education Goals.

The state report complements the national report released by the National Education Goals Panel.

Connecticut's report is organized into three sections and corre-

sponds to the six National Education Goals as follows: The Before

School Years (Goal 1), The School Years (Goals 2, 3, 4 and 6) and

The After School Years (Goal S). An appendix provides supplemen-

tary information about how Connecticut's education goals for 1991-

1995, adopted by the State Board of Education in 1990, compare to

the National Education Goals. In this report, indicators that have

been taken directly from the State Board's Comprehensive Plan for

1991-1995 are identified by the symbol of a small pencil (&).

Every effort has been made to provide objective indicators that measure Connecticut's progress in achieving the National Educa-

tion Goals. Where data are unavailable or unreliable, information on

selected programs that address the needs of children and adults is

presented.

Meeting The Nctional Education Goals

—@—— Report of the Governor —_-

Critical Links in Accountability

National Education Goals and Objectives for The Year 2000

Connecticut's Education Goals and Objectives 1991-1995

Our state has long recognized the importance of setting rigorous performance goals and establishing re- §able indicators to measure progress in meeting these goals. Since 1980, the Cor 1ecticut State Board of Education has been mandated to set long-term educational goals every five years.

While the National Education Goals for the year 2000 were being developed, Connecticut citizens were for- mulating the Connecticut State Board of Education's Challenge for Excellence: Connecticut's Comprehen- sive Plan for Elementary, Secondary, Vocational, Career and Adult Education — A Policy Plan 1991-1995. A comparison of the National Education Goals and Connecticut's education goals for 1991-1995 appears in thé appendix (see page 36).

Connecticut's Comprehensive Plan has two sets of goal statements. The five 1991-1995 Statewide Edu- cational Goals for Students (see page 37) articulate expectations for student performance and outcomes as the culmination of the public school experience. Eight policy goals focus efforts within the state/local partnership to implement essential operational changes to the state's public educational system which will enable the attainment of the student performance goals.

Local Board of Education Goals for Students

Change is dynamic. Anditis a dynamic process that must characterize our educational improvement ef- forts. Inthis school year, each of the state's 166 school districts will engage in the challenging process of adopting student educational goals consistent with the 1991-1995 Statewide Educational Goals for Students. While establishing goals, objectives and accountability are part of the broad national agenda, they are the essence of Connecticut's continuing agenda for educational improvement.

National Indicators of Progress

The national goals report contains mostly nationwide measures of progress and only some state-by-state measures. The National Education Goals Panel is developing proposals for more consistent indicators to use in both national and state reports in future years.

Connecticut's Indicators of Success

Since 1985, the Connecticut State Board of Education has reported annually on many of the state indica- tors presented in this first report. These indicators — noted with the symool of a small pencil (7 ) on the pages that follow — also are an integral part of the comprehensive education plan for 1991-1995.

Meeting The National Educatior Goals

Vil

Vili

overnor

Local Schooi and District Indicators of Progress/Strategic Profiles

The statewide indicators provide the basis for the most far-reaching accountability program ever under- takenin Connecticut: the Strategic School Profiles initiative for individual schools and school districts. The profiles will provide rich data on numerous indicators such as student performance on Connecticut Mastery Tests, attendance, high school dropout rates and graduation rates. The Strategic School Profiles are scheduled to be prepared by superintendents and presented to the public at meetings of local and regional boards of education annually beginning in 1992. The availability of the Strategic School Profiles with their key indicators — in some cases for the first time ever on an individual school basis — will assist public education in targeting efforts toward meaningful improvement toward meeting local, state and national education goals.

Higher Education Goals and College and University Profiles

Connecticut's goals for higher education also are aimed toward realizing the national goals. The 1989 Midpoint Review of the Higher Education Strategic Plan documents progress towards the three higher education goals of access, quality and responsiveness. The Department of Higher Education is mandated beginning this year to develop an annual Higher Education Profile for each college and university.

Annual Reports of Progress

Future annual reports toward meeting the National Education Goals — at the national, state and school/ campus level — will enhance accountability efforts already underway in Connecticut.

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

Goal 1 :

School Readiness

Readiness requires that

children receive appro-

priate care during all

stages of their develop-

ment

Comprehensive health

andeducation programs

. consistently have

made a difference in the

lives of disadvantaged

children

| v

d

|

4

The Before School Years

Achieving the goal of school readiness means that every child in Connecticut will

begin school eager and able to lean. While the majority of Connecticut children

do arrive on their first day of school ready to learn, an alarming number do not.

Children with physical and emotional disabilities, and children from low-income,

immigrant, non-English-speaking, and single-parent households are less likely to

be prepared for the challenge of formal education. These children are at risk of

educational failure.

The 1990 census data reveal tt. atin Connecticut, the overall population of children

and youth under 18 years old decreased by 8.9 percent since 1980: however, the

population under age 5 grew by 23.3 percent. Early indications are that blacks,

Hispanics and Asians comprise a greater proportion oi the under-5 population

than in 1980. Given the strong correlation between poverty and minority group

status, there is cause for concern about the school readiness of increasing

numbers of Connecticut children.

Readiness requires that children receive appropriate care during all stages of their

development. Early and adequate prenatal care is associated with improved

deliveries, while the lack of such care increases the risks of low-birth-weight

deliveries and infant mortality. Studies have shown that children born with low

birth weights are at greater risk of educational failure than those born within the

range of normal birth weights. For the majority of women, private insurance or

Medicaid pays the costs associated with their prenatal care. Yet, a substantial

number of women have no heatth insurance and have little or no access 10

prenatal care. Local hospitals, community health centers and private physicians

provide some of these women with reduced- or no-cost care, but the demand is

still greater than the supply.

In the formative years after birth, children require proper nourishment and

preventative health care in order to have the best possible chance of reaching the

levels of physical and mental maturity necessary for formal education. Immuni-

zation, lead poisoning screening, and nutrition programs have resulted in dra-

matic declines in the incidence of many childhood illnesses and have contributed

to a general improvement in the health of children.

Research has demonstrated that high-quality early childhood programs have a

positive effect on the lives of children. While all children can benefit from such

programs, children who are disadvantaged and children with disabilities reap the

greatest benefits from participating in them. Comprehensive health and educa-

tion programs such as Head Start consistently have made a difference in the lives

of disadvantaged children. When compared to children from low-income families

who did not attend high-quality early intervention programs, participants from

quality early childhood education programs have greater school success (e.g.

better grades, less need for special education services), increased future employ-

ability, decreased need for public welfare assistance, and decreased criminal

activity later in ite. Children with disabilities who attend early intervention

programs make significant gains in developmental functioning, particulary when

the intervention occurs during the earliest years of life.

Meeting The National Ed ization Goa. s

2

"The role of parents is

paramount

Young chiidren are the

most likely age group in

Connecticut to be poor

Heport of the Governor

While earty childhood programs play an ever-increasing role in preparing children for school, the role of parents is paramount. Parents (including single parents, guardians, foster parents and stepparents) have the principal responsibility to make sure that their children are ready and eager for school when the time comes. They need to spend time reading and talking with their children. Yet, with more and more children residing in households where the only parent or both parents work outside the home, it becomes more difficult for parents to adequately provide for their children's developmental needs. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of parents in their role as first teacher” can be enhanced if they have access to the training and support they need. Furthermore, research has shown that the quality of a child's life and his or her level of educational accomplishment improve when the parent's educational level rises. Illiteracy and educational failure are intergen- erational. Promoting lifelong leaming for adults — especially parents of young children — has multiple benefits.

Demographic Trends

Recently released 1990 census data indicate that the 5-and-under population in Connecticut was 272,294 children and has increased by 23.3 percent or 43,168 children since 1980. While specific data as to the breakdown by race/ethnic backgroundis not yet available, early indications are that significantincreases are evident in the Asian, black and Hispanic population groups.

Young children are the most likely age group in Connecticut to be poor. According lo census data, in 1970 nearly 9.3 percent of children under age 6 in Connecticut lived in poverty. By 1980, the percentage of children under age 6 living in poverty grew to 14.9 percent. In 1985, according to survey data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau, the percentage of children under the age of 5 living in poverty was 15.8 percent. Poverty rates for black and Hispanic children were significantly higher than those for white children. In 1988S, of all children under the age of 18 living in poverty, 6 percent were white, 32 percent were black and 62 percent were Hispanic.

In 1980, 34,554 or 18.9 percent of children under age 5 were from non-English-

speaking families. Of this group, 44.7 percent or 15,458 children under age 5 ‘Spoke Spanish at home. (New.data from the 1990 census are not yet available)

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

—@— Report of the Governor —@

Health and Nutrition

Preventative Health Care

A mother's ability to take advantage of health care during her pregnancy has a

dramatic effect on the circumstances surrounding the birth of her child and the

extent to which the child may experience developmental delays. Inthe 1990s,

access to health care generally has come to mean ability to pay. Typically, a

mother has medical insurance either through her employer or through a program

such as Medicaid. Yet there are many who have neither. In its January 1991

interim progress report, the Connecticut General Assembly's Health Care Ac-

cess Commission estimated that 25.4 percent of Connecticut children under the

age of 18 are uninsured. |

f Percentage of Low Birth Weight Deliveries )

BY SITY Rass Wich ign ie Dri ® While the overall percentage of low-birth-

2 weight deliveries remained between 6.6

and 6.9 percent during the three-year pe-

; 7 Bm TOTAL riod from 1988 through 1990, the percent-

BS Zz Zz 3, ware ages for black and Hispanic children were

d of Z: 2 Bt consistently and significantly higher. Provi-

i Z: OQ OT-ER-ASIAN sional data for 1990 point to a slight de-

I I = Prove onal crease in the incidence of low birth weight

gu BZ BE 87: : for black children.

i Source C7 Depanmen of ea!’ Se~ ces

Percentage of Births with Late or No Prenatai Care

1ReE-90

(Late « Care starting aher 1st tnmester Mothers Hepa orgin @ me ported)

® Many pregnant women in Connecticut. re-

gardless of race, receive late or no prenatal

care. Yet, the mothers of black and His-

z panic children are much more likely than

$ their counterparts to have late or no prena-

E tal care.

1988 1988 1990°

ii Source CT Department of Health Services 3

Meeting The National Education Goals

necticut's Healthy Start

program is to reduce the

Incidence of infant mor-

tality and low birth

weight

Despite Immunizing

more than 95 percent of

children by school en-

try...only 69 percent of

all urban 2-year-olds

have received a com-

plete basic series of im-

munizations

According to estimates,

approximately 80,000

Connecticut children

sufferfrom lead poison-

Ing

Solid data Is lacking as

to the total number of

Connecticut preschool

and school-age children

who suffer from or are

at risk of hunger

The obinctve ot ec. Sein Breton

e aovernor

Report 0

women and infants: The program is a joint effort of the Department of Health

Services and the Department of Income Maintenance. The objective of the pro-

gramis to reduce the incidence of infant mortality and low birth weight. Strategies

for achieving this objective include reducing the financial barriers to early, ongoing

and comprehensive maternal and child health care for income-eligible women,

infants and children upto age 7. Healthy Start provides funding for outpatient serv-

ices for eligible pregnant women and infants up to 18 months of age who are in-

eligible for Medicaid. Data from the Department of Health Services indicate that

curing fiscal year 1990, 4,977 women and 4,466infants — a total of 9,443 — were

served through the Healthy Start program. Data for fiscal year 1531 show a sig-

nificant increase inthe numbers served: 7,284 women and 9,587 infants — a total

of 16,881.

The objective of Connecticut's Immunization Program, administered by the De-

partment of Health Services, is to eliminate diseases that can be prevented by

vaccinations. The program strives to protect children from potentially fatal dis-

eases such as meningitis, polio, measles, rubella, mumps, dipthena, tetanus and

pertussis. During 1991, the Department distributed more than 537,000 doses of

publicly supplied vaccine to health-care providers in Connecticut to eliminate the

cost factor for those who cannot pay. Despite immunizing more than 95 percent

of children by school entry and providing education and outreach services, recent

Department surveys indicate that only 69 percent of all urban 2-year-oids have

received a complete basic series of immunizations.

The important role that immunization plays in preventing childhood illness and

lengthy periods of recovery has not gone unnoticed by Connecticut's legislature.

During its 1991 Session, the Connecticut General Assembly enacted the Univer-

sal Childhood Immunization Act, which promotes the full and timely immunization

of young children through parent education. expanded local outreach and coor-

dination between state agencies.

A preventable environmental hazard that threatens the heatth of children is lead

poisoning. The Lead Poisoning Prevention Program seeks to reduce and elimi-

nate exposure to lead through increased screening, education, medical care and

environmental follow-up. Itis estimated that approximately 80,000 children age

0-18 in Connecticut suffer from lead poisoning, which in many instances results

inleaming disabilities and other central nervous system problems. Urban and low-

income children and families experience the highest risk of exposure. Only 48

percent of the 80,000 children estimated to be lead poisoned were screened

during fiscal year 1991.

Solid data is lacking as to the total number of Connecticut preschool and school-

age childrenwho sufferfromor are at risk of hunger. However, a survey conducted

by the Hispanic Health Council in Hartford (1990) under the auspices of the

Community Childhood Identification Project indicates that significant numbers of

low-income families experience hunger. In addition, it was found thatfamilies who

are experiencing hunger employ strategies to cope. These strategies include

purchasing less expensive food, getting food from friends and relatives, sending

their children to eat with friends and relatives, eating at soup kitchens, and getting

groceries from food pantries.

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

eatth-caregprogramioriowirgome pragnar

Federal funds available

throughthe U.S. Depart-

ment of Agriculture are

distributed through the

State Department of

Education to heip pro-

vide nutritious meals

and snacks to pre-

The Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC),

a federal program administered in Connecticut by the Department of Health

Services, is designed to provide supplemental foods, nutrition education and

health-care referrals to low-income pregnant, postpartum and breastfeeding

women and to infants and children up to 5 years of age who are at nutritional/

medical risk. During 1990, 52,909 Connecticut families benefited from the

program; during 1991, 59,203 families participated.

Federal funds available through the U.S. Department of Agriculture are distributed

through the State Department of Education to help provide nutritious meals and

snacks to preschool children in day-care centers, schools, Head Start programs,

family resource centers and family day-care homes. According to the State

Department of Education, approximately $8 million is distributed annually. While

children in before- and after-school programs can also receive breakfast and

snacks and all meais during school vacation periods, nearly 90 percent of the

children served by this federal program are infants and children through age 5.

school children

fe Duily Number of Preschoolers Served a)

Department Of Education's Child Nutrition Program

® There has been a gradual in-

crease in the number of preschool

3 children served nutritious meals

2 EH Tou through the state's Child Nutrition

& E Pnvate Non-Pro Program.

x B Pubic Schools

E

Loca! Gov ; . 2 ® Nearly 18,000 infants and children

through age 5 were served daily in

1990.

Nv Source CT Department of Educaton )

Access to Quality Programs

Connecticut's Department of Human Resources is the lead agency in the state

charged with coordinating and administering our child-care delivery system,

which is an integral pant of early childhood programming. In July 1991 the

Department submitted to the federal Agency on Children and Families a three-

year plan for the administration of childcare services. Through the Child Care

and Development Block Grant Act of 1990, Connecticut is eligible to receive atotal

of $16 million over the plan period. Federal approval of the plan and application

is still pending. Key features of the plan address the issue of access 10 quality

programs for disadvantaged and disabled children by targeting child-care service

dollars as follows: to children whose parents are teenagers completing high

school; children who require protective services through the Department of

Children and Youth Services; and children who have siblings in care. The plan

also calls for providing additional payment to child-care providers who serve

children with special needs upon verified additional expense information. To

enhance the quality of the delivery system, the plan includes a commitment to

improve compliance with current state child-care regulations, to develop a com-

5

Meeting The National Education Goals

Report of the Governor

Teleint, i

prehensive training program for child-care providers, and to implement an

Incentive payment program for providers who meet certain standards of quality as

recognized by national child-care associations.

There are a number of places where children may participate in preschool

programs: day-care centers (private, local and state-funded); family day-care

homes; and earty childhood centers located in local schools. One of the more

The Family Resource comprehensive models in Connecticut can be found in the Family Resource

Centers offer compre- Centers. These centers, which served three communities in 1988 and eight by

hensive, community- 1991, offer comprehensive, community-based child-care and family support

based child-care and services located in public school buildings. Services include full-time preschool

family support services child care, and support and training for family day-care providers as well as op-

portunities for parents to gain and enhance parenting skills.

Disadvantaged children are served through a number of arrangements. Many

low-income families are eligible to participate in programs that provide no- or low-

costchild-care. One such comprehensive program, Head Start, provides children

under 5 with health, education, and social supports to help them achieve. In1990,

22 cities and towns in Connecticut operated Head Start programs, serving ap-

proximately 4,726 children. itis estimated that only 20 to 25 percent of all children

eligible for Head Start are currently served.

# Children with Disabiiees Age 0 - §

Estmated Need ve Number Served

1980 - 1990

ME ® An estimated 12,000 children

frm - age 0-5 in Connecticut may

2 1 LS emer have disabilities, and in 1990

< ) BCI Ws fri just over half of these children

; $522 Nav Seve were reported to be receiving

2 early intervention services

£115 gue? supported by state or federal

x funds.

BR I OU 1652

Source CT Otice of Poicy and Management

N —

J

Children with disabilities are those who are experiencing delays in their mental,

physical or emotional development. The definition also includes those children

who have a physical or medical condition (such as Down Syndrome) that has a

high probability of resulting in developmental delay. A significant percentage of

these children will require special education due to their disabling conditions.

There are no conclusive data on the total number of Connecticut children under

the age of 5 who have disabling conditions. There is only estimated data, based

on national research and federal projections. According to estimates from the

Connecticut Office of Policy and Management (OPM) based on 1980 and 1990

census data, at least 3 percent of Connecticut children ages 0-2 (a total of 4,143)

have a disabling condition. OPM also estimates that at least 6 percent of

Connecticut children ages 3-5 (a total of 8,049) have disabilities.

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

Connecticut is below the

national average In the

proportion of its 3-year-

oid children with disabill-

ties to whom It provides

services

The challenge for the

public schools Is to be

ready for all children

Parental involvement is

essentialtoachlid’s de-

velopment and key to

ensuring educational

success

€. Report of the Governor 9

State and federal law mandate that each state provide children ages 3 to 5 with

special education programs. Data from the Connecticut Department of Education

indicate that in 1991 approximately 5,400 children ages 3-5 were enrolled in

preschool special education programs across the state. (Comprehensive data on

the actual number served are available only for those children who receive

services from public providers, such as the Department of Education and the De-

partment of Mental Retardation.) Based on the available data, Connecticut is

below the national average in the proportion of its 3-yesar-old children with

disabilities to whom it provides services. However, the proportion of 4- and 5-year-

olds served in Connecticut is similar to the national average.

in Connecticut, children with disabilities under the age of 3 may receive services

from a variety of public and private providers. The six regional educational service

centers (RESCs) act as coordination centers and provide access to assessment

servces, planning services to meet identified needs, and referrals to appropriate

services for the birth-through-age-two population and their families.

Children with diverse backgrounds and developmental seveis and different

lengths of preschool experiences enter kindergarten and primary grades each

year. The challenge for the public schools is to be ready for all children. A program

of developmentally appropriate and positive instruction that nurtures the child-

hood desire to learn is critical. Practices that sort young children, based on

assesed school entry level abilities, into fixed groups with long-term identifying

labels must be scrutinized. Practices that convey the expectation for childhood

competence and high levels of skill development facilitate maximum growth in all

children. State and local support for developmentally appropriate preschool,

kindergarten and primary grade programs encourages child-centered cumiculum

and recognizes the active involvement of the child and tamily in learning.

Supporting Parents as the Child's First Teacher

Parenting is not an easy task. The demands on one's time and energy are

phenomenal. Yet parentalinvolvement is essential to a child's development and

key to ensuring educational success. To support parents and families in develop-

ing skills and resources to address the needs of their preschool children,

Connecticut has undertaken some key initiatives.

The eight Connecticut Family Resource Centers provide a contiuum of commu-

nity-based child- and family-support services. Through the Families in Training

(FIT) program, the centers employ an integrated approach of home visitation,

group meetings and monitoring of child development for new and expectant

parents. The centers also provide parent training and adult education programs

and serve as resource and referral centers for services related to parenting.

The Department of Children and Youth Services offers parental support and

training programs through community-based organizations. The Parent Educa-

tion and Support Centers (PESCs) provide education and support to parents of

children from birth through age 18, with special emphasis on parents of young

children, those with low income, those with limited English proficiency, first-time

parents, and minority parents. Atotalof 15 PESCs are in operation statewide, with

two located in low-income housing projects. The Department's Therapeutic Child

Care Initiative provides preschool programs for young children along with parent

support and education. These programs serve abused and neglected children

and encourage positive parent-child interaction.

Meeting The National Education Goals

Report of the Governor

LB

In addition, the Department of Education's Young Parents Program and the

Department of Health Services-sponsored Peer Education Program and Young

Parents Program also attempt to address the need for parental training and

education for teenage parents.

Kids Count

The Connecticut Commission on Children has initiated a five-year public policy

and education campaign on the importance of the first five years of life:

1-2-3-4-5 KIDS COUNT.

Working with state and local lawmakers, parents and business leaders, the

initiative is designed to encourage the development of new programs and the

retooling of existing ones. The KIDS COUNT goals include a coordinated and

integrated system of child care that is efficient and of high quality; prenatal care:

access to postnatal health care and nutritional guidance; expanded success-

oniented environments for both young teenage parents and their children; and

support systems to strenghten community and family life.

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

® Report of the Governor =i

The School Years

High Expectations for Students and Schools

The goal is to rank . On almost every measure of student achievement, Connecticut students rank

among the best In the among the best in the nation. The goal, however, is to rank among the best in the

world world. It has been said that we must raise our standard of performance or lower

our standard of living. In essence, this means that we have no choice. We must

have a high-performing educational system that gives students an opportunity to

leamin safe, high-quality integrated school environments. Students must develop

all the skills, knowledge and attitudes necessary to become productive members

+ of Connecticut's work force and our global society.

The high school graduating class of the year 2000 entered first grade in the fall of

1988. Each school day approximately 472,000 students attend more than 970

public schools in the state staffed by approximately 43,000 certified professionals.

All students can contrib- We must motivate and inspire all students to want to successfully complete high

ute to meeting the Na- school and engage in lifelong leaming. All students can contribute to meeting the

tional Education Goals National Education Goals if they see them as their personal goals. We needto offer

If they see them as thelr students a safe and supportive leaming environment, rigorous and challenging

personal goals curriculum objectives, and high expectations for performance.

High-quality teachers are the essence of a high-performing system. Connecticut's

reform efforts have recognized this with rigorous standards for the teaching

profession; the state's new teacher certification continuum reflects those stan-

dards. The continuum addresses every stage of an educator's career:

* teacher preparation standards, including a new requirement

for a subject-matter major;

* teacher induction procedures and assessments:

* professional development for the experienced teacher; and

* an alternate route to certification.

High-quality teachers and school leaders are committed to helping students

achieve the highest possible goals. In order to identify where improvement is

needed and how to achieve that improvement, educators and parents need accu-

rate, reliable and comprehensive information about what students know and are

able to do. This section of the 1991 progress report presents available statewide

measures of progress; it includes the most comprehensive set of indicators in this

report — reflecting Connecticut's major investment in accountability systems for

the public schools. It features Connecticut-specific data to supplement the report

of the National Education Goals Panel on Goals 2, 3, 4 and 6, which cover “The

School Years.”

Goal 2 There is no greater impediment to future success than failure to complete high

School Completion school. Reported in this section are Connecticut-specific indicators related to

graduation rates (the proportion of ninth graders who graduate from high school)

for the public school population and for students by racial/ethnic groups (e.g.,

white, black and Hispanic students). Information is also provided on students who

9

Meeting The National Education Goals

e Governor

compiete high school irom nonpublic schools and adults who recsive credit-based

local high schoo! diplomas or the Genera! Educational Development dipioma (GED).

Students at risk of academic failure and dropping out of school have been the

focus of a multiyear dropout prevention program in the state's Priority School

Districts. Many towns have spearheaded local initiatives to coordinate child and

family support services with school efforts on behalf of youth and families at risk.

In addition, the state's equivalent of the federal Upward Bound program has op-

erated in urban areas over the past five years and has posted a 92 percent high

school graduation rate; 95 percent of these graduates enroll in college.

Significant numbers of public school students, however, continue to leave school

before obtaining a diploma. Statewide information on public school dropouts will

be available in 1993, to supplement the high school graduation rate information.

& An increase in the proportion of ninth graders who complete high school

® The local public school graduation rate rose from

77.2 percent in 1986 to 78.8 percent in 1989, and

then tellin 1990 to 77.7. G

R

A

D

U

A

T

I

O

N

)

RA

TE

G

R

A

D

U

A

T

I

O

N

)

————————————

: : White ® The gap between the graduation rates of white stu-

dents and black and Hispanic students remains

Black large. The graduation rate in 1990 was 82.5 percent

“0 for whites, 62.2 percent for blacks and 51.1 percent

Hispanic for Hispanics. XE cp —— i+

06 87 83 89 90

YEAR

® The number of diplomas awarded in 1990 was the

smallest in more than a decade, due to the declining

~ number of births in the 1970s. This downward trend

is expected to continue through 1994.

R

A

T

E

CREDIT ar : oe ¢ i ® School completion is attained through the traditional

NONPUBLIG K through 12 method and also through other means.

V1 In 19890, 12.0 percent of all high school diplomas

granted were General Educational Development

(GED) diplomas and 4.5 percent were adult credit-

based diplomas. In 1990, local education agencies

(LEAs) granted 66.2 percent of all high school diplo-

mas, vocational-technical schools granted 5.1 per-

i, cent, and nonpublic schools granted Connecticut

students the remaining 12.2 percent.

Bi

id

io

mm

md

h

T

o

m

A

LEA

NU

MB

ER

OF

D

I

P

L

O

M

A

S

\

.

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

I Report of the Governor —@

Goal 3 The Connecticut Mastery Test (CMT) is the centerpiece of the state's K-12 testing

efforts. Information on student CMT performance in reading, writing and mathe-

Student Achievement rics in Grades 4, 6 and 8 is presented in this part of the report. The National

and Citizenship Education Goal on Student Achievement and Citizenship addresses the issue of

subgroup performance in student outcomes. On page 12, therefore, several

measures are used 10 assess the reduction inthe disparity in outcomes among the

state's subgroups of students on the Connecticut Mastery Test. Data on student

achievement is displayed by gender, racial/ethnic group and relative family in-

come. These are key indicators of the state's commitment to report on equality

of educational outcomes.

Formats for CMT results that are similar to the formats used in this report will be

employed in the Strategic Schoo! Profiles to be reported annually by each school

and school district in the state beginning in 1992.

&& An increase In student reading performance & An increase In student writing performance

& An increase in student mathematical skills

4 Connecticut Mastery Test Results Measured Against The State Goals a

: (Combined Results for Grades 4, 6 and 8)

Reading Writing Mathematics

Percentage Percentage . Percentage Fall 1990 pi a) Ros Or 3ova at or above

State Goal State Goal State Goal

56 18 43

80 an

|

E ° 70 5 707 3 70

T

© [1]

§ 60 g 5%

te —

3 40 $ 401 $ fio —

+

eg ; 39] : 0

8 20 Fa 207 — a 20

a 4

10 T T fais. i TY YT 10 T ~~ & ™ 4 10% T P——_— YT T

86 87 88 89 90 86 87 88 89 90 86 87 88 89 90

Ne School Year School Year School! Year

* The percentage of students scoring at or above the reading goals in Grades 4, 6 and 8 has risen from 48 percent in

1986 to 56 percent in 1990. The largest gain occurred between 1986 and 1987.

* Thepercentage of students scoring at or above the writing goals in Grades 4, 6 and 8 has shown no significant growth;

the figure was 18 percent in both 1986 and 13890.

* The percentage of students scoring at or above the mathematics goals in Grades 4, 6 and 8 has risen steadily from

34 percent in 1986 to 43 percent in 1990.

11

Meeting The National Education Goals

P Report of the Governor ms:

understanding, computational skills, problem soving/applications and measurement/geometry. The reeding test

measures students’ ability to understand nonfiction English prose at different levels of reading difficulty. In

writing, each student writes a composition which is judged on the student's ability to convey information in a

coherent and organized fashion. Listening skills measures students’ ability to understand information presented

on an audiotape. Reasoning/probiem solving measures students’ abilities in selected higher-order skills in lan-

guage arts and mathematics. Locating Information measures students’ ability to extract information from

schedules, maps and reference materials. Students who score at or above the state goal have demonstrated

superior performance on the skills, processes and knowledge associated with the particular content area

assessed. The remedial standards identify a level of performance that suggests the need for remedial

assistance.

g A decrease In the disparity in educational outcomes among the state's subgroups of students (by

race/ethnicity, gender, school district, parental Income and similar subgroups)

z CMT Results by income * &

(Combined Results for Grades 4, 6 and 8)

Percentage at or above state goal ® When compared by income level, the CMT

Reading Writing ~~ Math results show significant performance differ-

‘8 '90 88 ©0 ‘88 BO ences. Students in poverty conditions (i.e.,

Very Poor and Poor Students) are experi-

Very Poor Students 20 26 5 6 14 20 encing severe academic deficiencies as com-

Poor Students 33 39 8 8 2.28 pared to all Other Students.

Other Students 81. 66 18 21 42 =p

All three income levels show growth over

* Income categories are derived from participation in the time in all three tests.

federal School Lunch Program. "Very Poor Students” are

eligible for a free lunch; "Poor Students” are eligible for a

reduced-price lunch; "Other Students” are not eligible. 3)

4 SoM Results by Rages mnichy : 0) ® The CMT results by race/ethnicity continue

Combinae Resulis for Orades ¢, aac 8) to show large differences between white and

Percentage at or above state goal minority students. The largest differences

Reading Writing Math are inthe percentage of white students scor-

ing at or above the goal and the percentages '88 90 '88 90 ‘88 ‘90 of black and Hispanic students scoring at or

White 62. 85 18 21 AL SD above the goal. A higher percentage of white

yo BR 7: 6 13 "ys students scored at or above the goal in read-

Black ! 14 ing than Asian American students, butin both

Hispanic 8 X 5 BL. writing and math the percentages scoring at

\ AsianAmer. 56 56 19 19 46 3 or above the state goals are similar.

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

Report of the Governo!

& Adecrease in the disparity In educational outcomes among the state's subgroups of students (by

race/ethnicity, gender, school district, parental income and similar subgroups) [continued]

# CMT Results by Sex eo)

(Combined Results for 4,6 and 8) .

A higher percentage of females scored at or

POIGAnice 210 E50%8 said ou above the goals in both reading and writing,

Reading Writing al while in math a higher percentage of males

88 90 B V0 8 BO scored at or above the goal.

Females S55 58 19 22 36 41

\_ _/

P74 A decrease in the percentage of students below state standards in the basic skills

Connecticut Mastery Test Results Measured Against the Remedial Standard

(Combined Results for Grades 4, 6 and 8)

Reading Writing Mathematics

Percentage Percentage Percentage

at or below at or below at or belcw

Fall 1890 Remed:al Remedial Remedial

Standard Standard Standarc

25 15 14

| 801 801 80

| & 7] Rik 5 70]

T 60] E 601 E so = & = 80

ac) 9 5 4 [75) 4

P=] hi P 50]

Lo 40 4 3 40 9 ? 401

$ k = 4 = 1

301 304 T 30

= ; ——— 5 ) 8 )

8 204 s 20 1 Hi ati TA ® 201

$ i

a - ] :

10 T ™ T : 4 r 10 T Tr 2 4 4 10 Tr ™ T 5 T |

86 87 88 B89 90 86 87 88 89 90 86 B87 88 89 9°

— School Year School Year School Year

® The percentage of students at or below the remedial standard in reading has decreased from 30 percent in 1986 to

25 percent in 1990. The largest decrease occurred between 1986 and 1987.

® The percentage of students below the remedial standard in writing has decreased from 23 percent in 1986 to 15

percentin 1990 This decrease has not been steady. The percentage below the remedial standard increasedin 1988,

but decreased in 1989 and remained the same in 1990.

® The percentage of students below the remedial standard in mathematics has decreased steadily from 17 percent

in 1986 to 14 percent in 1990.

13

Meeting The National Education Goals

@ Report of the Governor =—@——

CMT Results by Grade

f GRADE 4 0) ® Fourth grade students have shown improved

: performance in math and reading over the six

LANG ARTS administrations of the Connecticut Mastery

Test. However, in language arts there has

been limited improvement. Writing scores

have fluctuated.

O

B

J

E

C

T

I

V

E

S

W

A

R

I

E

N

E

D

0

0

/

E

C

T

I

V

E

D

W

A

B

Y

E

R

E

D

ss 20

YEAR ® In 1990, the average number of math objec-

READIN tives mastered by students in Grade 4 was

21.2 (out of 25); language arts was 6.3 (out of

¥: 9). The average reading score was 48 De-

grees of Reading Power Units (out of 39), and

i a i : the average holistic score on the writing

85 ygap 90 J sample was 5.1 (on a scale of 210 B).

GRADE 6 TY ® Sixth grade students have shown consistent

improvement in math, with the average num-

ber of objectives mastered increasing from

23.1 to 24.5 (out of 36) from 1986 to 19390.

Writing and language arts scores have fluctu-

ated, but are above the 1986 levels. Reading

performance is essentially unchanged.

O

B

J

E

C

T

I

V

E

S

H

A

R

T

E

N

E

D

o

N

O

B

J

E

C

T

I

V

E

S

W

A

B

T

E

R

E

D

In 1990, the average number of math objec-

G | tives mastered by sixth graders was 24.6 (out

m of 36); the number in language arts was 8.1

++ READIN

A

V

E

R

A

G

E

R

E

A

D

I

N

G

S

C

O

N

E

$ 'e sh S (out of 11). The average reading score was

: 11 3 57 Degrees of Reading Power Units (out of

: i T T 99), and the average holistic score on the

N. YEAR 4 writing sample was 4.6 (on a scale of 2 10 8).

rr GRADE 8 |

ri ® Eighth grade students have shown, with mi-

nor fluctuations, strong annual improvement ANG ARTS

§ in all subject areas from 1986 to 1990. nN

oR

SN oN

WN:

WN:

® In 1990, the average number of math objec-

tives mastered by eighth grade students was

25.7 (out of 36); the number in language arts

was 8.4 (out of 11). The average reading

score was 63 Degrees of Reading Power

Units (out of 99), and the average holistic

score on the writing sample was 55 (on a

scale of 2 to 8).

O

B

J

E

C

T

I

V

E

S

M

A

S

T

E

R

E

D

O

B

J

E

C

T

I

V

E

S

m

A

S

Y

E

R

E

-

R

a

e

l

W

R

I

T

I

N

G

S

C

O

N

E

A

V

E

R

A

G

E

R

E

A

D

I

N

G

B

C

O

N

E

—

a

i

EA

-

m »-

n

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

——==== Report cf the Governor =————

Connecticut participated in the 1990 state-by-state National Assessment of

Connecticut students Educational Progress (NAEP) math assessment for eighth graders, and the

perform among the best results also are included in this section. Two other national indicators of student

in the nation on the achievement are reported annually and are included in this progress report:

Scholastic Aptitude student performance on the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and the Advanced

Test and Advanced Placement Examinations. Connecticut students on average perform among the

Placement Examina- best in the nation on these measures. Additionally, the proportion of Connecticut

tions students taking these tests is significantly higher than the national average.

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

£5 : 1990 Eighth Grade Mathematics Assessment 2)

Percent of Students by Performance Level

Perigrmance (evel Connecticut Nation

Level 200: Simple additive reasoning

and problem solving with whole numbers 98 % 97%

Level 250: Simple multiplicative

reasening and 2-step problem solving 72% 64%

Level! 300: Reasoning and problem solving

with fraction, decimal, percents and

elementary geometry 39% 12%

Leyel 350: Higher-level reasoning and

Re problem solving 0 0 7

A random sample of nearly 2,700 Connecticut public school eighth grade students participated in the first state-by-

state trial assessment undertaken by the 1990 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in mathemat-

ics.

Connecticut's average student score was 270, compared with the national average of 261. The scores show that

virtually all eighth graders in Connecticut have acquired skills involving simple additive reasoning and problem solv-

ing with numbers. However, dramatically fewer students (19%) appear to have acquired reasoning and complex

problem-solving skills involving fractions, decimals, percents, elementary geometric properties and simple algebraic

manipulations.

There appears to be no ditferenceinthe average mathematics proficiency of eighth grade males and females attend-

ing public schools in Connecticut. Compared to the national results, females in Connecticut scored higher than

females across the country; males in Connecticut scored higher than males across the country.

Connecticut students from disadvantaged urban areas had average scores (237) significantly lower than their

national counterparts (249). This seems to reflect the concentration of poverty in Connecticut's cities, which include

two of the poorest communities in the nation.

15

Meeting The National Education Goals

@— Report of the Governor ——@=

® Many more white students reached relatively high levels of performance compared with black and Hispanic students.

For example, while 23 percent of white students in Connecticut were proficient in the understandings expected of

eighth graders, 3 percent of black stu

ings.

dents and 2 percent of Hispanic students were proficient in these understand-

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

( 1990 Eighth Grade Mathematics Assessment 2)

Performance by Level and Race/Ethnicity

(Percent of students at or above given levels)

CONNECTICUT NATION

Level All White Black Hispanic All White Black Hispanic

200 98 100 93 90 97 99 89 23

2590 72 8 2 3 8 30 6 4 74 30 4 1

JOO 19 23 3 2 ¥2 3-5 2 3 7

¢& An increase In the Connecticut SAT scores at a rate greater than or equal to the national rate

SAT Results

® The Connecticut average verbal and mathemat-

ics scores onthe SAT declined in 1991, as did the

scores forthe nation. The combined average SAT

score was 897 for Connecticut and 896 for the

nation.

® In 1991, the College Board estimates that 81

percent of all Connecticut high school graduates

took the SAT; nationally, 42 percent of all gradu-

ates took the test. Generally, the more test-takers

in a state, the lower the average score.

® Overall, the average mathematics score has ex-

ceeded the average verbal score.

® The average Connecticut mathematics score has

fallen below the average score for the nation,

while the average Connecticut verbal score has

exceeded that of the nation.

TE >

joo

QO

(&)

07 cernacticut

ow 4 ..

< JUniiee States \

0 900 1 ;

J

«< go 4

{= of

WJ

>

< a0 ye -

[ §] 8] [1] | [ }) 91

o YEAR A

4 480 )

= US Math fo TO

O 4701 Y CY HAN

(&) ar

Vv 44809

=

<

wv 4504

ev WET CT Yerdal

<

= 4307 Lr —

(68 og ~ > ‘re » US Verdal oN

< BY 03. 85 87 89 ®

Wh YEAR if

16

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

Report of the Governor

Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT)

Percentage

of Students Verbal Math

Tested ** Average Average

Gender

Male 49 431 489

Female “ic 48 427 A418

Race

Asian 3% 413 517

Black 7% 341] 365

Hispanic 4% 354 391

Wine 83% 443 481

Family Income

Under $20,000 10% 360 397

$20,000 - $70,000 63% 418 454

over $70,000 27% 476 528

% May not total 100% due to rounding a

Advanced Placement Test Results

™

P

E

R

C

E

N

T

P

A

S

S

I

N

G

-

® Males outperformed females both in Con-

necticut and nationally, atthough in Connecti-

cut the gap betweenthe scores has narrowed

in both mathematics and verbal tests.

White students accounted for 83 percent of

the Connecticut SAT test-takers and

outscored all other racial/ethnic groups on

the verbal test. Asian Americans outscored

all other groups on the mathematics test.

Family income and parents’ education are

strongly correlated with SAT test scores. The

average total score for students from families

eaming more than $70,000 was 1,004 versus

an average score of 757 for students from

families eaming less than $20,000. Also, the

average total score for students with parents

holding graduate degrees was 1,010, versus

726 for students whose parents did not have

a high school diploma.

In May 1990, 72.1 percent of the Advanced

Placement (AP) examinations taken by Con-

necticut public school students received scores

of 3 or better (ona 1to 5 scale inwhich 3is the

minimum score required to receive college

credit). Nationally, 65.4 percent received

scores of 3 or better.

Between 1984-85 and 1989-90, the percent-

age of Connecticut public school seniors par-

ticipating in the AP program increased from

45106.7.

Eighty-five percent of Connecticut public high

schools offered at least one Advanced Place-

ment course in 1983-30.

Five percent of all 11th and 12th graders took

at least one Advanced Placement examina-

tion, but only three percent of minority stu-

dents did.

Meeting The National Education Goals

17

——@: Report of the Governor x Ss

Critical factors that affect student performance include the time schools allocate

10 instruction, the amount of time students spend on homework and on watching

television, and the school attendance rate. This section of the report includes

Measures of these fundamental components of leaming.

&& An increase in school attendance of students

® In 1990, average daily school attendance state-

wide was 95.1 percent. While currently above

the 1984 level, this rate has changed littie over

the last five years.

100

| [ET EAcines

LN

® Average daily attendance in the state's five larg-

vgs fe Je Bz ost cities has fluctuated each year and was 92.6

4 90 rcent in 1990.

YEAR Wf pe 29

A

T

T

E

N

D

A

N

C

E

(

A

V

E

R

A

G

E

DA

IL

Y

& An increase In time allocated to Instruction ® The time allocated to instruction has increased

atallgrade levels since the 1984-85 school year.

Districts scheduled an average of 964.8 hours of

elementary instruction in 1990-91 versus 951 in

1984-85. This represents an additional 4.6 min-

utes daily. Hours increased from 949 to 961.5 at

the intermediate level (an average of 4.2 addi-

tional minutes daily), from 947 to 965.6 at the

muddle schooljunior high level (6.2 minutes daily)

and from 943 to 956.7 at the high school level

(4.6 minutes daily). =

Student-Reported Time Spent

On Mathematics Homework

Dally — 19390

® In Connecticut, relatively few of the students

(5%) reported that they spend no time each day

on mathematics homework, compared to 9 per-

cent for the nation. Moreover, B percent of stu-

dents in Connecticut and 12 percent of students

in the nation spent an hour or more each day on

mathematics homework. Students were surveyed

as part of the 1990 National Assessment of Edu-

: gc cational Progress (NAEP) in eighth grade mathe-

30 45 60 or matics.

None 1

P

E

R

C

E

N

T

OF

S

T

U

D

E

N

T

S

a MINUTES PER DAY ,

18

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

Report of the Governor

Student-Reported Time Spent

Watching Television

Daily — 1990

é& 9» 0) ® In Connecticut, average eighth grade mathe-

x (BCTHUS| B matics proficiency was lowest for students

oo iz who spent six hours or more watching televi-

Fe 7 sion each day.

S LZ : Z ® In Connecticut, 16 percent of eighth graders

- rz 'Z reported watching one hour or less of televi-

a wr sion daily, while 12 percent of the nation's stu-

o 7 : i dents reported watching one hour or less.

x A BY BY BY BY Twelve percent of Connecticut's students and

Yor 2 3 4-5 § of 16 percent of the nation's students reported

less more watching six hours or more of teievision daily.

Ni HOURS PER DAY if

Connecticut-specific information is not currently available to measure student

competency in the following areas identified in the National Education Goals:

good dtizenship; community service; personal responsibility; percentage of

students proficient in two or more languages; and knowledge of the diverse

cultural heritage of the nation and the world. Given Connecticut's rich cultural di-

versity, many students speak more than one language. The state's support of

voluntary interdistrict cooperative programs recently has expanded multicultural

leaming opportunities to students in 100 of the state's166 school districts.

Plans are underway to report on student ability to reason and solve problems

through analysis of the 1991 Grade 4, 6 and 8 CMT results.

Statewide information on student performance in science and social studies

(history, geography and citizenship) is not available at this time. However, the

state plans to incorporate assessments of these areas in the new Grade 10

Connecticut Mastery Test scheduled to begin in 1993. The Grade 10 CMT also

will provide the first statewide comprehensive measures of high school students’

achievement in reading, writing and mathematics.

Goal 4 Achieving the national goals and Connecticut's goals will require major improve-

Mathematics ments in math and science education. In 1991, Connecticut was awarded afive-

year $7.8 million grant to improve science and mathematics education by the

and Science National Science Foundation. This initiative, which includes the Connecticut

Academy for Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, will bring

together resources from education, higher education and the private sector to

focus on strengthening K-12 cumiculum and assessment methods and cross-

teaching opportunities for college and high school teachers. Priority School

Districts with the lowest student performance and greatest need for improvement

will be the focus for improvement efforts.

19

@- Report of the Governor ——&@

The national goals and objectives also address the preparation of teachers, and

the need to increase the number of college degrees eamed — especially by

women and minorities — in mathematics, science and engineering.

An Alternate Route to Teacher Certification, recognized as a national model, is

placing talented people with backgrounds in mathematics, science and other

fields into high school classrooms. Under the leadership of the Board of

Govemors for Higher Education, the state supports college/school collaboratives

(including the Connecticut Pre-Engineering Program) modeled after Upward

Bound to reduce high school dropouts. Through another college/school program,

teacher aides in urban schools are being prepared for teaching careers in order

to help diversity the teacher force.

Measures of college math and science enrollment, by racial/ethnic groups and

gender, are reported. The numbers of college degrees awarded in math, science

and engineering also are included.

Enrollments in Mathematics and Scientific Disciplines

By Race, Ethnicity and Gender

Connecticut Colleges and Universities — Fall 1990

Mathematics and Science Nonmathematics or Sclence

Total %* Total

Blacks 4398 25 9,025

American Indians 31 0.2 390

Asian Americans 1,313 6.5 2,850

Hispanics 437 23 5,028

Whites 14,810 735 122.677

Nonresident Aliens 2,083 10.4 2.727

Women 6,549 325 88,719

Total for group as a percantage of all mathematics and science students. Percentages do not add to 100.0 because of a small

number of students for whom there are no racial or ethnic classifications.

Total for group as a percentage of all students in disaplines other than mathematcs and scence Percentages do not add to

100 0 because of a small number of students for whom there are no racial or ethnic classifications Source: CT Department of Higher Education 5

® Blacks, Hispanics, whites, and women were underrepresented among college and university students enrolled in

mathematics and scientific disciplines in 1830.

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

== Report of the Governor

Degrees Conferred in Mathematics and Scientific Disciplines

By Race, Ethnicity and Gender

Connecticut Colleges and Universities — 1989-1990

Mathematics and Science Nonmathematics or Science

Total %* Total %°

Blacks 109 3.2 1,052 43

Amencan Indic ns 11 0.3 66 0.3

Asian Americans 153 45 469 1.8

Hispanics 59 1.7 513 2.1

Whites 2.724 79.3 20,160 82.8

Nonresident Aliens 265 7.7 920 3.8

Women 913 26.6 14,433 59.3

a Total for group as a percentage of all mathematics and science students Percentages do not add to 100.0 because

of a small number of students for whom there are no racial or ethnic classifications

b Total for group as a percentage of all students in disciplines other than mathematcs and science Percentages do

not add to 100 O because of a small number of students for whom there are no racal or ethnic classifications

\" Source: CT Department of Higher Education gr

® The same patterns of under- and overrepresentation among racial, ethnic and gender groups in 1990 enrollments

also appear with regard to degrees conferred by Connecticut colleges and universities during the 1989-1930 aca-

demic year.

® Trend data over the past five years indicate that the absolute number of degrees conferred in mathematics and

scientific disciplines has decreased from 4,070 to 3,434 and the relative proportion of mathematics and scientific

degrees has decreased from 14.7 percent to 12.4 percent of all degrees awarded.

Meeting The National Education Goals

{ B Report of the Governor =i)

AT Tan -

Goal © Recognizing the need for Connecticut-specific information, the 1988 Connecti-

Safe Disciplined Cut legislature authorized the first statewide survey of 6th through 12th grade

’ students conceming the extent of alcohol, tobacco and other drug use. The 1989

and Drug-Free survey of a five percent representative sample of public and private school

Schools students provides the statistical benchmarks in this repont. Indicators include stu-

dent substance use in the last 30 days; regular use (i.e., six or more times in the

last 30 days); and substance use by high school seniors in Connecticut, the

Northeast and the nation. Baseline information on students’ reports of problems

related to substance use also is included. The State Department-of Edueation

plans to survey students in 1992-83 and incorporate the results in the 1993

Strategic School Profiles.

&& A decrease in the prevalence of student use of alcohol, tobacco and drugs

Substance Use In Last 30 Days ® Connecticut students, regardless of grade level, re-

ported that the most frequently used (at least once

within the past month) substances are alcohol, ciga-

# 60 v \ rettes and marijuana, followed by prescription pain

’ medications used outside of medical supervision,

B GR&3 "uppers,” cocaine, "downers," inhalants and tranquil-

B GR&12 izers. Only 0.6 percent of high school students re-

ported using crack-cocaine in the past 30 days

These measures of current or monthly use describe

substance use that is ongoing versus students who

reported “experimentation” with a particular sub-

stance only on a single occasion.

White students exceed both minority groups in alco-

hol consumption, cigarette and marijuana use and

prescription drug abuse. Among nonwhite students,

Hispanic students reported more use than black

students of all substances except marijuana.

‘P

ER

CE

NT

OF

ST

UD

EN

TS

-

High school students residing in large cities reported

lower levels of substance use than students in

nonurban areas.

Measuring Connecticut's Progress Toward

== Report of the Governor ch

Substance Use In Last 30 Days ® Compared with the most recent and directly

High School Seniors * comparable national data available atthe time

of the Connecticut survey, Connecticut high

school seniors reported a similar pattern, but

a higher rate of use of alcohol, cigarettes and

marijuana. Although relatively small propor-

tions of students reported using cocaine, Con-

necticut seniors show a higher use rate than

students nationally.

® Relatively large numbers of Connecticut stu-

dents are estimated to be using illicit sub-

stances regularly (six or more times per

month). Of the 270,595 students enrolled in

Grades 6 to 12: 38,100 smoked cigarettes regularly;

24,400 drank alcohol regularty:

* US and Northeast data are for 1988; 14,800 smoked marijuana regularly; and

CT data are for 19889. 1,900 used cocaine regularly.

(

P

E

R

C

E

N

T

OF

ST

UD

EN

TS

® More than half of Connecticut's high schoo!

seniors reported that they had seen drugs

Alcohol and Other Drugs being sold in school at least once dunng the

In School past year. Significant proportions of students

reported going to class under the influence of

alcohol or other substances, or missing schoo!

0 ™ altogether as a consequence of substance

; use.

® Significant proportions of high school stu-

dents reported problems with their parents,