Certified Index

Public Court Documents

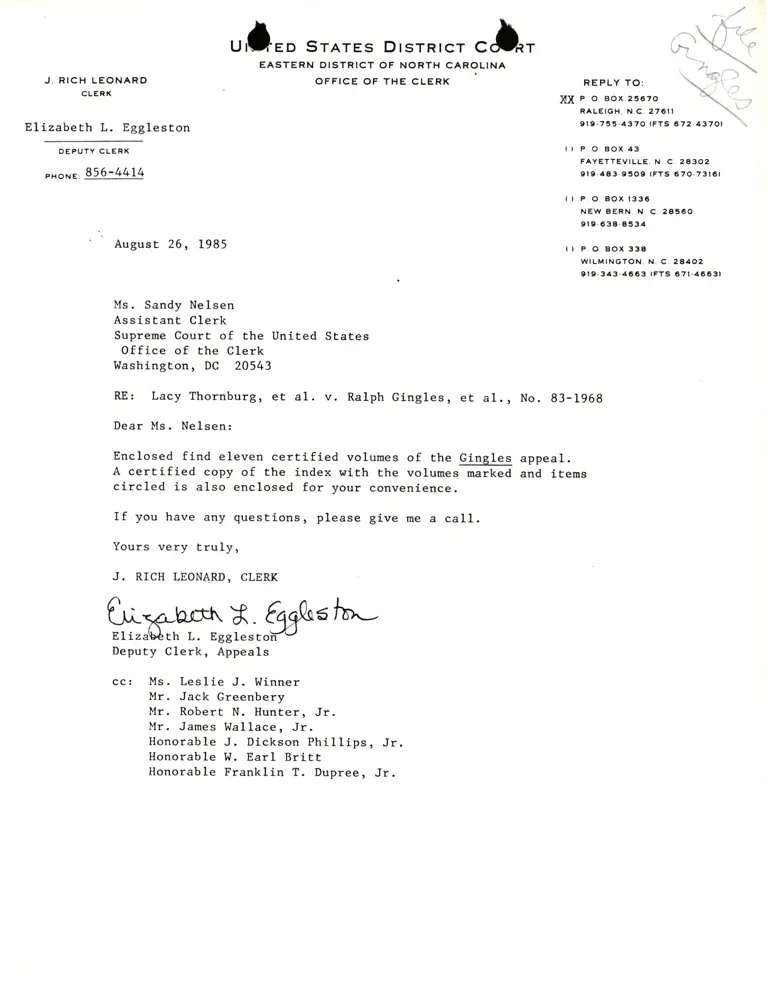

September 16, 1981 - August 26, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Certified Index, 1981. 696ff476-d692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3e43805c-bcee-4fb2-b41b-5304fa7cd951/certified-index. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

,JED srArEs Drsrnrcr cll.

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

OFFICE OF THE CLERKJ. RICH LEONARO

CLERX

Elizabeth L. Eggleston

OEPUTY CLERK

PHoNE: 856-44L4

xx

REPLY TO:

P. O AOX 25670

RALEIGH. N,C, 276II

9te.755.4370 rFTS (,72.4370t

t) P. O BOX 43

FAYETTEVILLE. N, C, 2A302

0re.483.9509 IFTS 670.73r6r

P. O. BOX t336

NEW BERN, N, C, 2A560

9t 0-63 e-6 5 3 a

P. O. BOX 3!8

WILMINGTON, N, C. 2E4O2

tl g.3/r3.4663 (FTS 671.46O31

(t

August 26, 1985 tl

Ms. Sandy Nelsen

Assistant Clerk

Supreme Court of the United States

Office of the Clerk

Washington, DC 20543

R.E: Lacy Thornburg, et a1. v. Ralph Gingles, et al., No. 83-1968

Dear Ms. Nelsen:

Enclosed find eleven certified volumes of the Gingles appeal.

A certified copy of the index with the volumes-marked and items

circled is also enclosed for your convenience.

If you have any questions, please give me a call.

Yours very truly,

J. RICH LEONARD, CLERK

Cr.>e'nlxrr S, €q#5 lD'--

Elizablth L. Egglestoha

Deputy Clerk, Appeals

cc: Ms. Leslie J. Winner

Mr. Jack Greenbery

Mr. Robert N. Hunter, Jr.

Mr. James I.Ia1lace, Jr.

Honorable J. Dickson Phi1lips, Jr.

Honorable W. Earl Britt

Honorable Franklin T. Dupree, Jr.

4L7

DAV YEABI ' o i,--t1-;1 ,; DFt;IAND

PLAINTIFFS DEFENDANTS w/81-i066-Civ-

42 U.S.C. Sects. L973, 1973(c) & 1983 & 14th & 15th Amendments to U.S. Constitution

Federal Question - action challenges the apportionment of the N.C. General Assembly

& the N.C. representative districts for the U.S. Congress - 3 Judge Court requested. tt

-.>- , ATTORNEYS

{r. J. LeVonne Chambers Mr. James Wal}ace, Jr.

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, Wallaspl- Deputy Attorney General

Adkins tr+*f+e*,-+;*- for Legal Affairs

Suite 730 E. Independence Plaza N.C. Attorney General's Office

951 S. Indeper:Jence B1vd. p.O. Box 629

Charlotte, NC 28202 Ralelgh, NC 27602(704)37s-846L (9L9)733-3377

Mr. Jack Greenberg

Mr. James M. Nabrit, III

ur. .N1s- Lo.^, G.o,'.,"o}

Attorneys at Lar^l

-le-€elunbus-Girele 99 Hudson St.

New York, NY 10019-10013

t?92>r8?&?97- (2r2) 2r9-r9oo

For Plaintif f-Intervenors : *r: :r-'he I'onorahie j . _li_cl1son P'ri -i. l.i.ps, Jr.

-'u, ge, Iot,rt.. ili.rcuit Ji . of Appea 1s

P.i). iox 3oL7

Dtrrhan, llc 7-77!.:2

---l

I certifY the foregoing to b'e a true

and correct coPY of the original'

I1r. Robert N. Hunter, Jr.

CHECK

HERE

FILING FEES PAID

;t 0803

& 82-545-Civ-

I %erp,r cTNGLES.%nruo BURToN,%*u, I l/rrm EDMrsrEN, in his capaciry as I

BELFIELD, andVOSnpH MOODY, on Behalf rhe Artorney General of N.C.; ftXnS

of Themselves and A11 Others C. GR-EEN, Lt. Governor of N.C. in

Similar1y Situated rlis Cap4city as Presi-dent of the N.C.

HfuE nF'Y #3ffi#:;*rt.[i'.mTi iili;r"

Three-Judse courr, fl ! E gJ [-/ \ ;i' ROBERT w. s?EAR[,IAN, ELLoREE M. ERwrN--

RUTH T. SEMASHKO, I^ITLLTAM A. MARSH, -fR.,

?heHonorable J. Di-ckson phillips, Jr. and JOHN A. I^IALKIRI' in_Their Official

TheHonorable Franklin T. Ouprel, Jr. Capacities as Members of the State

TheHonorable 6r. Earl Britt . Board of Elections of N.C.; and THAD

T.lpA, in His Capacity as Secretary of

ALAN V. PUGH, GREGORY T. GRIFFIN, the State of N.C.

MASON McCULLOUCH, PAUL B. EAGLIN,

ETHEL R. TRorrER, GTLBERT LEE BocER, *(substituted as defts. L2|L7/8L)

DAVID D. ALI'IOND, JR., RAY I,IARREN, DIS3)YEiIY ETPINES ON---.-I--.-

JOE B. R0BERTS' Plaintiff-rnvervenors 6AUSE EtUff."U. 83.lqCt(per order of 7 /22183) (crrE THE u.s. crvrL

'TATUTE

uNDER wHrcF{ THE .ASE

IS FILED AND WRITE A BRIEF STATEMENT OF CAUSE)

AEtorney at Law

P.O. Box 3245

Greensboro, N.C.

(919) 373-0934

IF CASE !!AS

FILED IN

FORMA

PAUP E fi IS

Nearest !i 1 ,000

37183 I 181

,]ATE

27 402

AECEIPT NUIABER

Lklil{€rruidu,oui ';, ,lJ-- l-uoo-LIV-)

82-545-CrV-5

9lL6/Bt COMPLAINT -

)/23/3L

PROCEEDINGS

pltfs. pray that the court convene a 3-Judge court; certify this .action

l: 1.. "","1"": ".:ion;.declare.rhar A.rricle-rr, Secr. 3(3) & Secr.-;i;;"of-the N.c. constitution are in violation of iect. 5 of voting RightsAct' of 1965 & enjoin defts. from enacting any legislation & fiom conducting, supervising, partJ-cipating .in, or certifying the results of anyelection pursuant to an apportionment which \^/as enacted in ,""ora"r,". ,/these constitutional provisions until & unless these constitutional pro-visions have been submitted & approved in accord.ance wl42 U.S.C. Sect.

L973c1 declare..Article rr, Secr. 3(3) & secr. 5(3) ro be in violation ofSect. 2 of the voting Rights Act of 1965 & the 14rh & 15rh Amend.menrs ofthe U.S. Constitution & enjoin defts. from enacting any apportionment ofthe N'C. Gen. Assembly in accordance w/these provisions from conducting,etc. the results of any election for the N.c. Senate or Ehe N.c. Houseof Reps. -pursuant to any apportionment enacted in accordance w/theseconstiEutional provi-sions; declare that apportionment of the N.C. Senate

& N.C. House as enacted in'Chapters 800 & 821 of the N.C. Session Lawsof 1981 violates equal protection clause of the 14th Amend. of rhe u.s.Constitution; declare that the apportiorunent of tire N.C. Senate & N.C.

House as enacted in chapters 800 & 821 of the N.c. sessi.on Laws of 1gg1dilutes the vote of black cj-tizens & denies pltfs. the right to use theivote effectively; declare that the apportionment of the rep. districtsfor the U.S. Congress as enacted in Chapter 894 of the Session Laws of

1981 denies pltfs. who resi.de in 2nd Congress. District their right touse thei-r vote effectively; & award costs of this action, includ. attyslfees to pltfs . - w/ attachments ttIssued SUMMOIIS ro U.S. Marshal v/ZB5 & cy. of Complaint. rr

I

)/25/87

)/29/eL

)/718L

lrl-0II-oN,FoR EXTENSION gF TIME - deft. moves that Ehey be granted an add. 30 daysfollowing.Lo/7/81 or unEil 71/6/8L in which to file rheir .""pon=ir"pleadings - w/cs.

ORDER - defts. are grant.ed an exEension of time to file responsive pleadings t9& Complainr to & includ. IL/6/8L _ (LEOI{ARD, Clerk) cc counsel

ORDER. oN DISCOVERY - counsel are directed to stipulate to the Court on or before

lO/L9/81 the amt. of time required for discovery in this action includ.

a date rvhen all discovery will be completed - (LEONARD, M.) cc counselttfile Eo J. Dupree tt

- notice of the pend;ncy of this action & of the application for i.njunctive

& declaratory relief be given to che Chief Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals,

4th circuit, in order that he may designate inaccordance w/2E u.s.c. sec

2284 2 other judges Eo siE r,//the undersigned judge as members of this

court for hearing & determinaEion of this action; cc of this order to

bc mailed to Honorable Harrison Winter, Chief Judge of U.S. Court of

Appeals, Balti-more, MD, & to counser of record - (DUPREE, J.) (crv 0.B.

1163, p. 196) cc counsel & J. Winrer rr

tt

the

tt

Case

ORDER

CIVIL OOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

PLA I NII FF

RALPH GIi{GLES, ET AL.,

OATE I NR.

LolT /BL ,7(lb)

L0/t 6/B

10/ 30/ Br

i

I

I

l

I

t,9

ig

DEFENDANT

RUFUS EDMISTEN, ET AL.

PROCEEDI NGS

DocKEr No B1-903-cr

,lidated wiBl{0;66-C

PAGE Z OF- PAGtrS

r. Qr- q/, (-.TU

J-

iMEl'loLANDuM IN SUPPORT OF SUGGESTION 0F MoOTI{ESS AND MOTION TO DISMISS - by defts.

. - w/cs. ErefftOet'It of Alex K. Brock - w/attachments. rr

DESIGNATION 0F THREE-JUDGE COURT - Honorable J. Dickson Phi11ips, Jr., U.S. CircuiI .1udge, 4th Circuit, & Honorable trrl . Earl Britt, U.s. District Judge fori E'D'N'C', to serve w/the Honorable F. T. Dupree, Jr. in the hearing oI determination of this action, the 3 Eo constitute a district court of

i -

judges - (wrNTER, J.) (crv o.B. #63, p. 207) cc counser rr

to/ 2L/ BL

L0 /22/ : jL 0RDER - the tiqe by which counsel must stipulate eoncerning

quired for discovery in this act.ion is extended

M. ) cc counsel & panel

PLAINTIFFS I RESPONSE TO DEFENDANTS ' MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF SUGGESTIoN OF }IooT-

NESS AND I"IOTION TO DISIIISS - motion to dismiss should be denied & sug-

gestion of mootness should be rejected - w/cs & attach. cy. to panel t.

)1qT-IQL-EQ8-EXLEI{EI-aN-9,E-TrUE- defts. pray the court for an order rhaE rhey neednot file responsive pleadings to this action until such time as the

Court grants, or delines to grant, defts.r ].O/2l /8L motion & until suc

Eime as Ehe Court Ordered that the Complaint be answered - w/cs. cy.

w/proposed Order to J. Dupree - cy. panel tLL/2/8\ ORDER - time within which Defts. may file responsive pleadings is extended until

such time as the Court grants, or declines to grant, defts. October

21, 1981- motion and orders that responsive pleadings be filed.

(Dupree J.) (Civ.08#63,p.272) cc to counsel & J. Britt a pHi1lips.

LL/2/8L 17(la) tJorrcE oF DEPosrrroNS - of william Hal-e & Terence sullivan on LL/g/gI at Raleigh.

tz/-\ cys. to J. Britt e phillips. w/cs.

LL/3/8L

ey 0RDER - parties are.directed to have complcteci.discovery and be ready for a final

pre-tria1 conf erence on or before z/19/82 - (DUPREE, J. ) (crv o.B. 1163,

i p. 285) cc counsel & panel

Er1l13l81 19(rb)PL\rNTrFFSr'ME)roRaNDlllI rN opposrrroN To DEFIINDANTS, r,IorroN To srAy - w/cs. cy. Eo

t

,@ . tnsTsu, oltlilnrr-nrro*s oF FACr - by der:s. & prrfs. - w/artach. cy. Eo panel E,e, 'UULL0^\-I0-SUEBLEIIENT C9XBLAINT; RULE-Ul-Oj-RJiv.p. - p1tfs. move rhe Courr ro

permit them to serve a SupplemenEal Complaint to set forth transactio

& occurrences which have happened since 9/L6/8L & further request, thag

' i Court order defts. to answer SupplemenEal Complaint at same time that

ahey answer original Complaint - w/proposed SupplernenEal ComplainE _

w/attach & cs. cy. to Panel t

22(lb)ME)IORANDUM IN SUPPORT oF PLAINTIFFS' MoTION TO SUPPLEMENT CoMrLAINT - by p1rfs. -I I w/cs. cy. to panel

cy. of entire file to date sent to {. phillips, J. Dupree & J. Britt. E

}JOTION T0 STAY PROCEEDTNGS - defts. move the Court to stay al1 proceedings in rheaction & to extend time w/in which defts. need file answer to the Com-plaint until such time as the Gen. Assembly reconvenes & redraws its

r 1r(

@

the amc. of t.ime re-

to 10130/81 - (LEONARD,

ca.l l !A PE! ',,/75)

CIVIL OOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

PLA INTIFI:

RALPH GINGLES, ET

DATE NR.

i tt/rglat

D EFENDANT

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN,

DOCKET NO 81-803-cr

/81:1066-cET AL. rlidatgd wpncr J oF

&

LL/ Ls / 8L6D

PROCEEDI NG5

ORDER - defts. I motion to dismiss as moot the claims brought under Sect. 5 of the

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. Sect. L973c is denied; defts.r motion for

stay must be denied in order to permit full preparti.on of the case for

expeditious adjudici-ation; pltfs.r motion to file a supplement to the

complaint is allowed; defts. are directed to file responsive pleadings

to the original complai-nt & supplemental w/in 20 days of this date -

(DUPREE, J.) (CIV 0.8. 1163, p.322) cc counsel & panel EE

SUPPLEIENT TO COMPLAINT - p1tfs. pray that the Court grant relief prayed for in

Complaintl declare that..apportionment of the N.C. House as enacted in

Chapter 1130 of N.C. Session Laws of 19Bt violates the equal prorectjon

clause of the 14th Aatend. to U.S. Constitution & enjoin defts. from

participating in, supervisi-ng, conducting, or certifying results of anyi

election pursuant to this apportionnent & from enacti-ng any apportion-

ment i.n the future which has representation districts which are not

equal in size; declare that the said apportionnent of the N.c. House

dilutes the vote of black citizens & denies p1tfs. & other class rnem-

bers the right to use their vote effectively because of their race in

violation of Sect. 2 & Sect. 5 of the voting Rights Act of 1956, as

amended, in violation of the l4th & 15th Amend. of U.S. constitution,

& in violation of. 42 u.s.c. sect. 1981 & enjoin defts. from participar-

ing in, supervising, conducting or certifying the results of any elec-

attyrs. fees to pltfs. - w/attach.

rDEiENDAtirSr )ioTto-l{ TO RECCNSTD_EB_U_ENW - def ts. move rhar rhe

Court a-rcePt for filing & consider the defts'reply, that the Court

reconsider its Order of LO/L9/31, as that Order regards deftst Motion

to Stay Proceedings, and that Court afford defts. opportunity to be

heard ori their Motion to Stay proceedings - w/cs. cy. panel tt

DEFE)JD.L\TS' REPLY TO PLAINTIFFS, MEMOMNDI]M IN OPPOSITI0N To DEFENDANTS' MOTION

T0 STAY - w/cs . cy. Panel rr

Order - This action is before the court on deftsr motion of 1L/23/87, seeking

reconsiderat.ion of this courtts order denying deftst earlier motion

for a stay of the proceedings. The motion is denied. Defts. are

directed co file responsive pleadings in accordance rv/ the schedule

established in rhis ocurt's order of. lIlfg/81. (CIV. o.B. 1164, p. 54)

(DUPREE, J.) - cc to counsel & Judges'panel.

Defts. having ful1y answered each & every allegation contained in the

Pltfrs Complaint and Pltf's Supplemental ComplainE, ancl having set for

their defense, pray thaE. thj-s court cleny the relief requesEed and

dismiss the Complaint w/prejudice - w/cs. cy. to panel.

OF DEPOSITIOI.I - pltf. to depose Senators Helen Marvin and Marshall Rauch

on L2/l7l3L at 9:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. in Gastonia, N.C. - w/cs.

Issued DEPOSITIOI.I SUBPOENAI; to U. S. Ilarshal wlcy. ,rf )lotice. cl/. Panel

l{oTro); To Qu_Agx_s_uBrqur4_I_o&IN_-THE_ALTERNATIVE.EOR A PROTXCTIVE- OR.pFR - defts.

pray rhe Court for an order quashing said subpoenae or in Ehe a1E.

tion purusant to this apportionment & from enacting any apporti";;;;

Iin Ehe future which has the purpose or effect of diluting the vote of

Iblack ci-tizens;& to award the costs of this action, includ. reasonable Iattyrs. fees to pltfs. - w/attach. aal

-UQI_10-N._T9__B,EEQ}]_SIDEB_U_ENW - defts. move rhar rhe I

Lt/ 23/ 8L

:!

L2/7/BL

l

I

i

12I9/BL

I

I

I

I

I

I

itz/ q / at

i

I

I

A:iSiiER. -

26a(ta) \0TICE

,@

-4

I

EU

-rl

.d

'1\ztutsL @

directing that depositions be sealed - w/cs. cy. Panel

30(1b)3RIEE rN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS' )IOTION TO QUASH SUBPOENAE 0R Il{ TI{E ALTERNATIVE

FOR A pR9TECTIVE ORDER - b.r defrs. - w/cs. cy. Panel

///// /// 1175)

DC lllA

(Rev. l/75)

DocKEr ruo. 81-803-5

|olidatgd w/ B1-1066-Cij.

PAGE a oF_pacrs i

I

OATE ] PROCEEDINGS

NOTICE OF SUBSTITIUTION 0F DEFTS; RULE 25(d)(1) F.R.Civ. P. - p1rfs. give norice

that Robert LI. Spearman, Elloree M. Erwin, Ruth T. Semashko,

William A. Marsh, Jr., and John A. Walker, in their official

capacities as members of the stare Board of Elections of N.c.,

are substituted for R. Kenneth Babb, John L. stickly, Sr., Ruth

Semashko, Sydney F. C. Barnwell, and Shirley Herring, as

defts. in Chis case - w/cs. Cy. to panel. r

NOTICE OF POSTP0NEMENT OF DEPOSITION - pltf. gives notice that the depos of Sena-

tors Marshall Rarich and Helen Marvin scheduled f.or L2/L7/8L are

postponed until such Elme as the Court shall rule on Defts.t

Mot. to Quash Subpoenae or in the AlE. for a protective order -

PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFENDANTSI MoTIoN To QUASH SUBPoENAE oR IN THE AITERNA-

I

TIVE FOR A PROTECTIVE ORDER - w/cs. cy Panel td

.RDER - derts'''ol:-': ,a:=l^:y:1"::i:-':-f i1:1:-c:::::111 r'?"r d"r-'?:'y.''

I

is vacated; a nerir schedule will be established at a later date

(DUPREE, J. ) (CrV O.B. 1164

L2ILTIBL

L2lt8/8L

L2/ 3L/ BL

Ll s/ 82

Ll2L/82

32 (1a

DEPOSITION OF I'IILLIAM K. HALE - taken L7/L6181 in Raleigh, N.C.

in separate envelope.

- w/nxnibirs 1-5

t

N.C. - w/gxhibits

P.C

.to

t

\"{Arltd- q

L/29/82

2/2/82

2/ 3/ 82

OF TERRENCE C. SULLMN - raken LL/9/BL in Raleigh,

1-12 separately.

oF TER&EIICE C. SULLIVAN, VOL. II - raken LL/16181 in Ral h. N.c.

MOTION TO CONSOLTDATE AND REQUEST FOR THREE-JUDGE couRT - defts. move the court

DEPOSITION

DEPOSITION

MOTION PRO

I

i ononn

prder a complete consolidation of this actj_on w/No. g1-1066-civ

5 for all purposes & defts. request a three-judge court to hear

the actj-ons - w/cs. cy. to panel r

HAC vrcE - defts. move the courE that Jerris Leonard & Associates,

& specifically Jerris Leonard, Esq. & Kathleen Heenan, Esq.,

members of District of columbia Bar be admitted pro hac vice

this court as add. counsel to defts. - w/propo".d ord.r E ""cy. Panel

- Jerris Leonard & Assoc. & specifically Jerris Leonard, Esq., & Kathleen

Heenan, Esq. is admitted pro hac vice to this court. as add.

counsel to defts. _ (DUPREE, J.) cC cotrns"l & pane1.

ORDER - It is ordered t.hat notice of the pendency of Pugh vs. Ilunt and of the

applicaEion for injunctive and declararory relief be given Eo

the Chief Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circ-uit,

in order that he may designate in accordance w/ 28 U.S.C.

92284 two other judges Eo sit w/ the judge as members of this

courr for hearing and determination of this action. It appear

ing to t.he undersigned t.hat consolidation of the two actions

would be appropriate, the Chief Judge is requested to give

consideraton t.o designatirrg El'.e same panel to hear Pugh as has

been designated to hear Gingles. (CIV. O.B. 1164, p. 202)

(DUPREE, J.) - cc to panel, Judge Winter & counsel of record.

(Original in B1-1066-CIV-5).

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

PLAINTIFF

MLPH GINGLES, ET AL

DEFENDANT

RUFUS EDMISTEN, ET AL

oc 11lA

(Rev. l,'75)

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

DEFENDANT

PJJFUS EDMISTEN, eE al. cons

D ocK Er r.ro.B1-803-Civlidare{ u/g1-1966-6i

PAGE ) OF- PAGES

PLAINTIFF

RALPH GINGLES,

DATE

I

et al.

PROCEEDINGS

ORDER - this acrion is consolidated w/No. 81-1066-Civ-5 for further proceedings

- (DUPREE, J.) (CIV o.B. 1164, p. 245) cc counsel & panel

STIPULATION - disc. can be completed by the 30th day following rhe U.S. Arry. Gen

eralrs decision on the issue of whether to pre-clear each &.r.iy

"p-portiorunent plan last enacted by the N.c. General Assembly; during

disc. period, response to j-nterr. shal1 be due by the 15th day follow

ing service of interr. or requests Eo produee; also, stipulations re

apportionment plans - w/attach. cy. panel t

l'{oTIoN To CERTTFY THE CLASS - pltfs. request the Court to enter an order allowingthis action to be maintained as a class action on behalf of all blackresidents of the State of N.C. whoc are registered to vote - w/cs &

43 (lb)MEIIOLANDU}I

attach. cy. Panel

IN SUPPORT OF PII,INTIFFS' MOTIOX TO CERTIFY THE CLASS - bY PItfS.w/cs. cy. Panel

iAFFIDAVIT 0F MLPH GINGLES - cy. panel .-

iAFFIDAVIT 0F FRED BELFIELD - cy. panel

I^{FFID^{VIT 0F JOSEPH P. MOODY - cy. panel

lltorroN To FLRTHER SuPPLEI.'IENT coMpLArNT - w/cs & arrach. sECoM suppLEMENT To

i CO)IPLAINT. cy. Panel

lb)]IEvORANDtnl rN SUPPORT OF PLATNTIFFST MOTION TO SUPPLEIENT COMPLATNT - by p1tfs.

i 2/tBl82

2/ 22/ 82

3/L7 /82

3/2s/82 W

P

t

tt

Et

E

t

w/cs. cy. Panel

AFFIDAVIT 0F SIPPIO BURTObI - cy. panel

OR-DER - pltfs.r mot. to amend their original complaint is allowed - (DUPREE, J.(CM.B. 1165, p. 4) cc counsel & panel

SECOND SUPPLEIENT T0 COMPLATNT - p1tfs. pray that the Courr granr relief prayed

for in Complaint & Supplement to Complaint; declire that the appor-

tt

t

tlonment. of the N.c. Gen. Assembly as eontained in chapters 4 & 5 of

the ExLra Session Law of 1982 dilute the vote of black citizens & denpJ-tfs. & oEher class mernbers the right to use their vote effectively

because of their race & enjoin defts. from participating in the resul

of any election pursuant to this apportionment & from enacting any

apportionment in future which has the effect of diluting vote of blac

declare that defts. have an affirmative dury to eliminate effects of

past purposeful discriminarion & E.o assure that. pltfs. & other black

ciEizens have fair opportunity to elect. reps. to N.c. Gen. Assembly;

declare that chapters 4, 5 & 7 of ExE.ra Session Laws of 1982 do not

afford pltfs. & other b1::ck citizens a fair opportunity to elect reps

of tlreir choosing; enjoin defts. from participating in, supervising,

conducEing or certifying the results of any election pursuant to said

apportionment which does not. elirninate effects of pasE discrimination;

& award costs of this action including reasonable attys.r fees to plti

3l2e/82 A,\SI'JER To SECOND SUPPLEI'IENT T0 COMPIIINT - defrs. pray rhar rhis Courr deny rh6

relief requeste! & dismiss the complaint ru/preiudice - w/cs. cy. Pane

53(1a)DEFE)iD.\NTS|FIRSTSEToFINTERRoGAroRIES,u{DREOUESTSFoRffi

lr

3/3L/82 is+(r.lNorrcE oF

- w/cs. cy. Panel t

DEPosrrrOll - pltfs. to depose Gerry cohen ar 9:30 a.m. on 4/6/82; wi1li

K. tlale at 2:00 p.m. on 4/6/82; RoberE A. Jones ar 9:30 a.m. on 4l7lB

& Daniel Long aE 9:30 a.m. on 4/8/82 all in Raleigh, N.c. - w/cs. cy.

Panel t

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

PLAI NTI FF

RALPH GINGLES, eE aI.

oATE l NR

4/2/82

4/ sl 82

4l 6l 82

DEFENDANT

RUFUS EDMISTEN, et

PROCEEDINGS

TSTIPULATION OF CLASS ACTION - parti-es agree thaE it is in besr inreresr of all parl

i ies to this acEion for action to proceed as class action; parties fur-

ther stipulate that the class of all black residents of N.C. who are

registered to vote is an appropriate class; add. , -parties in Gingles

. do not object to exclusion of the black named pltfs. in Pugh, et aI. ,

i. from the class certified in Gingles - w/cs. cy. panel tt

i56(1a)DEFENDANTSI SECOND SET OF INTERROGATORIES AND REQUESTS FoR PRODUCTION (GINGLES) - i'Z) w/cs. cy. Panel tt(y I10Tr0N 0F PLArNTrFirs, ALAN v. PucH, er al. v. JAIIES B. HUNT, JR., er a1. (gr-

f\ 1066-CIV-5) FOR LEAVE T0 FILE SUPPLEMENTAL COMPLAINT - w/cs & arrach.rr(sa) IAFFTDAVTT OF COIINSEL FOR PLATNTTFFS AUll v. pucH, er al. (81-1066-crv-5) ion--"'--;

LEAVE TO FILE SUPPLEMENTAL COMPLAINT SETTING FORTH GROUNDS _ of ATthuT i

J. Donaldson - w/cs. cv. Panel

4/B/82

4/e/82

4123182

4/Ls/82

t^

4/22/82 16)\-/

I5Y DEFENDANTS'

tt,

RESPONSE T0 MorrON 0F PLATNTTFFS ALAN v. pucH, er a1. v. JAIIES B. HUNT

JR., et aI. (81-1066-Civ-5) FOR LEAVE TO FILE SUPPLEMENTAL COIIPLAINT -w/cs. cy. Panel

- inot. of pltf- to file a supplemental complainr (81-f066-Civ-5) is allowed

- (DUPREE, J.) (CIV O.B. 1165, p. 55) cc counsel & panel rt

SUPPLE)IENTAL COMPILINT 0F PLAINTIFFS ALAN V. PUGH, et al. (81-1066-Civ-5) - plrfs.pray that the prayer for relief of the original complaint be granted ein add. that the Court declare the actions of the N.C. Gen. Assembly Iat the 1982 Section Extra Session null & void as to legislative redis-tricting; declare that N.C. has failed to enact State Senate and State,

House redistricting plans in accordance w/the Constitution of N.C.; & :

not adopt the 1971 redistricting plans on r,rhich to base interim elec_ itions on the grounds that said 1971 plans are unconstitutional - rv/cs

& attach. ttCase file to J. Dupree w/request for handling of dipositive mot. (p1tfs.' Iot. toi Certify the Class). tt

}IOTION FOR PARTIAL.VOLUNTARY DISMISSAL - pltfs. move that the Courr granr rhemprLrr. urvvE LrliaL Lrte uourE BranE Engm Ileave to dismiss voluntarily, & w/out prejudice, their 14ch Claim for I

relief insofar as it relates to the N.c. disEricts for the u.S. congres:

- w/cs. cy. panel

STIPULATION OF EXTENSION OF

& OIiDER

0F EXTENSTON oF TrME - parties stipulaEe that pltfs. must responddeft.'s. lst rnterr. & Requests for production by 5/13 /82 - r/"=.(Approved, LEONARD, M.) cc counsel & panel

,NOTICII OF HEARING FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND oTHER EQUITAtsLE RELIEF - by

- wfcs. cy. Panel

APPLICT\TION FOR HEARING FOI1 PRELIMINARY INJUNCTIoN fu\D 0THER EQUITABLE RELIEF -pltfs. move that the Court adopt a temporary plan for apportionment

for gen. & prinary elections in 1982 from submitted plans; establish in

its discretion a May 1982 hearing date bv wirich tirne parties to the

licigation wil1. submiL a single member districE plans & data for Court

to consider in adopcing a single member districting plan for N.C. Gen.

Assembly; adopt & order the N.C. StaEe Board of Elections to publish

said plan & to conduct interim elections on basis of such plan; establil

dates for filing periods of notice of candidacy for N.c. Gen. Assembly j

primary elections; enjoin defts. from conducting any elction under the

i1971 redistricEing plan or any plans rejecred by Atty. Gen. & decrare i

suclt plans unconsi-tuEional; that Ehe Eemporary plan of electing membersi

of the Gen. Assembly remain in effect unEil such time as a valid legis-i

lative redistricting plan can be passed upon by N.c. Gen. Assembly; & I

EhaE Court retain jurisdicEion over this matter - w/cs. cy. Panel tt

@

@

Et

I

ORDER

r9

@

,@

tt

to

tt

plufs

tt

DC.rllA Fat '1/75)

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

PLA I NTI FF

R.ALPH GINGLES, et al.

DEFENDANT

RUFUS EDMISTEN, et

DATE NR. PROCEEDINGs

4/23lBZ Q((Ib))lE)loRANDIrlI IN SUPPORT oF PLAINTIFFST MOTION - by pltfs.

4/27182b7) )IOTION FoR ExTENSIoN oF TrME - defts. move rhe Courr fc\-/

DocKEr r'io. 8l-803-Cil

olidated w/81-1066-Ci

PAGE / OF- PAGES

tt

@

9

I

ORDER

i

i

ORDER

I

i

I

I

I

;'.-

4/ 30 /82

as a class action to be maintained on behalf of all registered black

voters in N.C. - (DUPREE, J.) (CIV 0.B. 1165, p. lL2) cc counsel & Panel

Moticn for T.R.O. heari-ng held before ,j. Dupree in Raleigh, }tr.C. A:thur J.

Donaldson f or the pltfs . ; James l^lal1ace , Jt . for the d.efts . PItf rs mot

denied.

FffIDAViT of Alex K. Brock, Executive Sec::;Director of the State Board of Electio{

for I'1 .C. - by defts. (fitea in Open Court) cq\^.

;'4/29/82,69a(la)DEFENDANTS' FrRST sET oF rI{TERRocATORTES AND REQuESTS FoR pRoDUCTToN (pucH) -,"r/.1cy. Panel rrl

NOTICE 0F MOTION FOR PRELII{INARY INJUI{CTION OR TE}IPORARY RESTMINING ORDER - bv ipltfs . cy . Panel rr;

l'IorrON oF PLATNTTFF's, ALAN v. PUGH, ET AL., FoR pRELTMTNARy TNJUNCTToN oR TEMpoR-i

ARY RESTRAINING ORDER - pltfs. move for a preliminary injuncrion or

ii 1RO enjoining defts. from accepting for fliing notices oi candidacy or

conducting or performing any procedure enabling canclidates to file for I

69d (1b) BRrEF rN

the irl-C. State House or the N.C. State Senate under those districting

plans adopred or amended by the N.c. Gen. Assembly at its Third Extra

Session of the Gen. Assembly on 4/27/82 - rv/cs & artach. cy. panel rt

SUPPORT OF MOTICII FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION OR TE}{PORARY RESTRAINING ,

ORDER - cy. Panel rE

0

@

GA

i'IOTICE 0F PARTIAL I,IITHDMWAL OF INTERROGATORIES - def ts. w/clrarv Def rs. r 2nd Set of

Interr. & Requests for Production (Gingles) propounded, 4/5/82 w/rhe

exception of Interr.22 insofar as it relates to Pltfs.'claims chal-

lenging the apportionment plans for the N.C. Senat.e & House - w/cs. cy.panel tt

ORDEIT - plrfs.' (Pugh) llot. for a Temporary Resrraining Order is <lenied - (DUPREE,

J. ) (CIV O. B. ll55 , p. 136) cc counsel & cy. panel r r

)1O1II0)J FOR EXTENSION OE TIIIE - Dt:Ets. pray tlre Court that they be granted an

extension of fime to June 3, 1982, in rvhich to respond co the Pugh

pLrfs' Application for i{earing and for Preliminary Injunction and Other

Eqtritable Relief. P1rfs. stipul;rce EhaE sr.rch an extension would be

both reasonable and proper - w/cs. Cy. to Panel.

ORDER - It is Ordered that t.he defEs. are granted an exEension of Eime E.o June 3,

l9B'2, in which to respond ro the Puglt plcfsI Application for Hearing

for Prelim. Injun. and Other Equicable Relief. (DIIPREE, J.) - cc Eo

counsel & to Panel.

mli

l

ml

DEPOSITION - Pltfs. will depose Gerry Cohen, 9:30 a.m. ' Tues., Inlay 25,

L982; William K. Hale, 2:00 p.n., Tues., Yay 25, L982, Daniel Long'

9:30 a.m., [r'ed., )tay 26, 1982 & Terrence Sullivan, 2:00 P.s., Wed.,

)lay 36, 198l at Ehe \.C. Ceneral Assembly, Raleigh, I'i.C. - w/cs.

v t. 1/73;

'i

mk

I

nk

4/ 30/ 82

0

sl3/82

5 l6 /82

5 /7 /82

5l13l82 cy. oI ltr.

File :i2

- lu/cs.

I10TI0N FOR EXTENSI0N OF TIME - defts. move the Court for to & includ.5125/82 ro

respond to Supplemental Complaint of Plaintiffs (81-1066-Civ-5) and rhe

Ilot. for Determination that Action May Be !,laintained as a Class Action

w/cs & proposed Order. cy. Panel tt

- defts. have to & includ. 5/25/82 to respond to Supplemental Complaint (Af-

1066-Civ-5) & the Mot. for Determination that Action May Be Maintained

as a Class Action - (DUPREE, J.) cc counsel & Panel tt

- pltfs.'Mot. for Partial Voluntary Dismissal is allowed; & p1tfs.'Mot. for

Certification of a Class'Action is allowed & this action is certified

to lIs. Leslie !{inner to prepare an appropriate discovery stipulafion

and have it signed by counsel and returned Eo him. (Lcr. Eo Ms.

L,lnner from Judge Dupree).

5/ L3/ 82 i5(2a)NorICE oF

oc l11A

(Rev. 1,.75)

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

I

t--------

I

I

is /t2/82

I

I

I

i5/14/82

I

:

i

I

15/25/82

s/26/82

5/23/82

,7/2/82

7 /L6/82

t,5 /7 /82

7/22/82

7/23/82

7/26/82

leus. ro

I

I

I

PLAINTIFF

RALPH GINGLES, ET AL

oArE I "* I

@

@

@

@

e

i

6.n lor"ry

82 (2b) i.IElo.

MOTION TO CONSOLIDATE -

w/cs.

DEFTSI RESPONSE TO PUGH

OTHER

Pane1.

DEFENDANT

RUFUS EDMISTEN, ET AL

PRocEEDTNGS consolidated w/gL-Lo66-CIV-5

o oz-J+J-t IV-)

#2 CoNTINUED------

defts. in 81-803-CIV-5, 81-1066-CrV-5 & 82-545-CrV_5 _

Cy. to Panel. Orig. in 82-545-CIV-5. mk

PLTFSI APPLICATION FOR HEARING FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNC. &

EQUITABLE R-ELIEF - w/attached exhibits & cs. Cy. to

mk

DEFTS'

ORDER -

suPPLE. COMPLATNT oF PLTFS. ALAN v. pucH, et a1. B1-1066-crv-5 - defts.pray for denial of'requested relief & dismissal of complaint e

supple. complaint -.w/cs. Cy. to panel. tt

MOT. FOR EXT. OF TIME TO RESPOND TO PUGH PLTFS, MOT. FOR DETERMINATION TTIA

ACTION MAY BE MAINTAINED As A CLAss ACTIoN - foT 20 days to Te-

spond to pltfsr mot.- w,/cs. Cy. to panel. ttdefts. have 20 days following receipt by defts. of the pugh p1tfs, responsto defts' 1st set of interr. & request for proarr.t-. to respond

to Pugh pltfs' mot. for deternination that action be maintained.

as class acti-on. (DUPREE, J.) CC to counsel. Cy. to panet. tt

RESPONSE To PUGH PLTFS' Mor. FoR cLASs cERTrErcATroN - objecting - w/cs.

Cy. to panel.

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONSE TO PUGH PLTPSI MOT. FOR

to panel

CLASS CERT. - w,/cs. Cy.

cg1'r

cgw

t

B0a

6?

i@

'6ilv

l

i

i

l

1

i

I

l

I

Gil\J

RESP0NSE oF CAVANAGH PLATNTTFFS T0 MorroN To qfJqp,iJD/qE.- w/cs. cy. panel

ORDER - derts.r moE. to consoliclate this acrir"ri,;lf;i:"si-so:-civ-5 and g1-1066-

tt

civ-5 is allowed; ruling rv/ouE prejudice to parti-es' right to

file any mots. pursuant to independent i-ssues ruhich may arise

during litigation; counsel are in cavanagh directed to confer &

presnet Court w/proposed disc. order ,rtri.-tr will adequately en-

compass inreresr of all parEies - (DUPREE, J.) (CIV O.B. 1166,

p. 96) cc counsel & Panel r

GINGLES PLT\INTIFFSIOBJECTION TO PUGH PLAINTIFFS' NIOTIoN FoR CL\SS CERTIFICATIoN -

Gingles plEfs. move court to deny that part of the pugh mot. for

class ccrt. that requests cert. of class of black citirer,s; limi

any oEher class certified in Pgg[ to repi-esentation only on

claims not involving raciar aiscrimination; allor,r those pugtr plt

who are black opporEunity to excrude themselves from GingleJ

class if they desire; alt.. aIlow named pltfs. in Gingles ,t any

other members of Gingles to exclude themselves from pugh crass -

cv. Panel tE

)IOTION TO FILE THIRD SUPPLEIIENT TO COMPLAINT AND TO AMEND COMPLAINT - by ptrfs. -

w/cs & proposed THrRD SUPPLE)IENT To rHE coMpLArNT AND I\IEND),IENT

TO COIIPLAINT. cy. Panel r

SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS ' }IOTION TO FILE THIRD SUPPLEIIENT To COIIPLAINT

AND TO AyEND CO)IPLAINT - by plrfs. - w/cs. cy. panel r

8/ L8/ 82

S.

87 (2b))1E)10R.L\DUY IN

DOCKET r.ro. El-

pacr 8 oF_pAGES

)c 111A

Rev. 1.75)

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET FPr-ilAR-7.t4.80.70M.4398

Clerk

jj

PLAINTIFF

RALPII GINGLES, et al.

DEFENDANT

RUFUS EDMISTEN, etc., et a1

cross-motion for summ. judg. (LEONARD, Clerk, by Forcum, Deputy

cys. to counsel for service.

DATE

8lL9 /82

El 30/ 82

)/3/82

e/20/82

) /2e/82

,2 /22 /82

. /6 /83

L/t2/83

L/Lt /83

)./ra/83

L/t8/33

L/ 3L/83

1/2/83

:/11/83

t/23/83

DrscovERY srrPuLATroNS - disc. in ce.ve4egh. ro be comptere by L0/g/g2; disc. in

Pugh and Gingles to be complete by 3/L/83; parries in Pugh and Gingles

rvi1l be prepared to go to trial by a/L183; & parties in Civarragt rfll

be prepared to go to trial by 4lL/83 as to those issues that are not

disposed of by sum. judg. - cy. to J. i;upree by counsel - cy. panel.t

OR.DER - disc. stipulation submitted by counsel is approved - (DUPREE, J.) (CIV

0.B. 1166, p. 236) cc counsel & Panel rl

ANSI{ER T0 THIRD SUPPLEMENT TO COMPLAINT - defts. pra\/ rhar Courr deny the relief

requested & dismiss the Complaint w/prejudice _ rv/cs. cy. panel tt

i lCase fi.l-e to-J. Dupree for rul-ing on pltfs. r mot. to file 3rd supplement to

i^ I Complaint & to amend Complaint.

lrl I onoen - pltfs' motion to supplement & amend their original complaint is allowed.

X | (CIV O.B. #67, p. I1O) (oUprcr, J.) CC to counsel. cgv

19) ITHTRD suPPl,EltENT To rHE coI'IeLATNT & AMENDMENT ?o coMpLArNT - w/cs & exh. A. cw

lI9 ir.rorron FoR sut,r,lARy JUDGI"TENT by pltf=. :i*f;,r6J, cV. ro panel. cam

iY_a(zUl l'1Ei.1oP'ANDULl SUPPoRTTNG PLTFS' MorroN FoR sult. JUDG. - w/cs & attachments. ccni

@ luorroN To TNTERVENE - Ralph Gingles, Sippeo Burron, Joseph Moody, Fred Belfield,

I ind. and as reps. of class of all black residents of N.C. who are

i registered to vote move to intervene as defts. in B2-545-cIV-5.-by

6 I plrfs. - w/ consenr of counsel in g2-545-Cl\r-5i -w/cs..{f i prErs. - w/ consenr or counsel in g2_545_Cl\r_5i _w/cs. jj

\96/ I MOTION (AND ORDER) FoR EXTENSION OF TIIE - defrs. granred ro and incl. Jan 1g,\-/ | i983 to respond to Cavanaugh p1tfs. mot. for summ. judg. and to file

gg tzJl

f00 (]a) PLTtr'S

l,rorro,., ro*

DEPOSITION of i"lichael S. Michalec w/exhibits cy. to panel

ORDER - unopposed motion of the Gingles plffs. to intervene as defts. in

Cavanagh-is allowed. Gingles plff . are al1owed 15 days from this date

to respond to Cavanagh plffs'moti_on for summary judgment. (Dupree J.)

(CIV.08#68,P.154 ) cc to panel, cc to counsel-

DEFTS I S RESPONSE TO PLFFS I MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND DEFTS' CROSS-I4OTION

FOR SUi"IMARY JUDGI4ENT - by defts. Brock, Spearman, Erwi-n, Semashko,

Marsh & Browning- w/cs. cy. to panel

I'IEI4ORANDUII IN SUPPORT OF DEFTS I RESPONSE TO PLFFS I MoTIoN FoR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

AND rN suPPoRT oF DEFTS'cR.oss-MoTroN FoR SUl4-ltARy JUDGMtrNT - w/cs.

cy. to Panel

IIRST SET OF IIJTERR. & REQUESTS FOR PFODUCTIO}I:

w/cs. Cy. to Panel.

SUlll4ARY JUDGI4ENT by deft.-intervenor, Ralph Gingles, joining

defts. in oppsoing mot. for sum. judg. by Cavanagh p1tfs. &

for surn. judS. in favor of defts. (This motion is limited

Cavanagh) - vr/cs. Cy. to Panel.

FXOUESTS FOR ADI1ISSTON -

cgw

state

moving

to

Cglt/

LOz(Zb) DDTT.-I}.]TDRVEI]ORS'ilEIIiO. IiI OPPOSITION TO PLTtrS' I.1OT. FOR SUI,I. JUDG. & IN

I suppoRT or DEFTS' & DEFT.-rNTERVENop.s' rlorrolls FoR suM. JUDG. - w/cs

I

I & attachments . Cy. to Panel-. cgl^,

-t\

1)r"-tRESPONSE To DEFENDINTS cRoss-)lorrolr r0R sLln1Ar{y JUDGiIENT -(re: 12/22/s3 }1or.)

tlby pltfs. Cavanaugh; w/ attach. Affidavit of l,lichae1 }lichelac & cs. j

ISSUED NOTICE OF NON-JURY TRrAL at Raleigh, l-0:00 a.m., Mon., 7/25/83, Ctrm. H7,

7t,h F7oor, PO & Cthse., before 3-Judge Court, J.Dickson Phi77ips, Jr.,

US Cir.Judge, F.T.Dupree, Jr., Chief ll .S.D.J., d W. EarT Britt, U.S.D.

DocKEr No B1-SO]-C

PAGE 9 OF-PAGES

pRocEEDrNGs consolidated w/91-1066_Civ_5 &

DC utA

(Rev. l/75)

I

DATE

i "*l

DocKEr n o81-803-Civ-

PAGEl!_OF- PAGES

PROCEEOINGS

ot-tuoo-t,tv-

B2-545-CrV-5

RESPONSE T0 DEFENDANT-TNTERVEITORS CROSS MOTrON FOR SUIftIARy JUDGMENT - by

plaintiffs- w/cs. cy. Panel.

Cavanag

jj

]J

Fri. , 7/15/83 rn U}

, before Judge Dupree.

2/23183

317 /83

s/5/83

/22 /83

6/27/83

7/7 /83

7 /L2 /83

7 /L4/84

7/21/83 1t2 (

1113 (

'1L4 (

I

104 (2b)

I

I

I

ros (2h)

I

I

I7,iryi

I

i

aOi

@

rloD)

@

@

NOTATION OF SUPPLEMENTAL AUTHORITY IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT-INTERVENORS'

(GINGLES) MOTION FOR SllI'ftIARY JUDGMENT - by def r. Intervenors

i-n Cavanagh v. Brock. -w/cs.

TSSUED NOTICE OF FINAL PRE-TRIAL coNFERENcE at 7O:OO a.m.,

Ctrm. #7, 7th Floor, pO & Cthse. , Raleigh,N.C.

Case file with Judge Dupreers office.

Ltr. to counseT rescheduTing Pre-trial conf. to ?hurs., 7/74/83 at 70:00 a.m. jri

Not].ce of Hearing on Pending Motions set for L0:00 a.m., Thursdag, JuTg 7, 7983

;Ctrm. #fr 7th FLoor, P.O. & Cthse, RaTeigh, NC, before J. Dupree,

!

J- Phillips & J. Britt.; cg. counsel-, J. phiLTips, J. Dupree, J. Britt,i

Ct. Rptr. jj ,.

|\IOTION FOR ADIIISSI0NS PRO FLAC VICE - by Gingles p1tfs. _ w/cs . Cy. to J. Dupree. al

Nlotion Hearing held before 3-Judge Ct. in Raleigh. Leslie J. I'iinner for the plffs

James Wallace & Kathleen Heenan for the defts. Mot. on pro Hac Vice'

is allowed. Time: 2 3/4 hrs. catu'

i'IOTION FOR A PRO'r'ECTIVE OR RESTRAINING ORDER by defts . - w,/cs e supporting affida-

vit of James $ial-1ace, counsel for defts. cy. to panel. cgr.,

DEFTS' ANS. TO SUPPLEIIENT TO THE COMPLAINT: AIIENDMENT TO THE COI,IpLAINT & ADDITION

OF PARTIES PLFF. IN PUGH V. HUNT, ET AL, No. 81-1005-CIV-5 - w/cs.

ICy. to Pane1. cgh.

PLFFS' RESPONSE TO DEFTS. MOT. FOR PROTECTIVE ORDER - w/cs e supporting affidavit,

of Leslie Winner, counsel for plffs. Cy. to panel. cg\r

ORDER - Entries 107, I09 & 110 shal1 be sealed pending further order of the Ct.

(Crv o.B. #105) (oupn-ne & BRrrr, J. ) cc to counsel & panel. cg\,l

PRE-TRIAL ORDER -- w/stipulations, contentions, extribits, witnesses, designation I

of pleadings, ETT: B days. Signed by courrsel & accepted by Ct. CV.

Ito Panel. clll,l

Pre-Trial Conference held before Judges Dupree & Britt in Raleigh. Leslie Winner,'

3b)onrcwoAN?s' PRE-TRIAL BRrEF - Cgs. to Panel - orig. to J.Dupree for file

3b) PRE-TRIAL I4EMORAND|IM OF PLAINTTFFS - RALPH GINGLES, ET AL - Cgs. to Panel - Orig.

to J.Dupree for fiLe.

i

I APPENDTX TO PRE-TRIAL EI'IMORANDUM OF PLAINTIFFS RALPH GINGLES, ET

I

I PaneL - Orig. to J.Dupree for fiLe.

I

',MOTTON TO MODIFY (PROTECTIVE) ORDER bg Gingles PLffs. w/consent of

i Cti. to PaneL - Orig. to J.Dupree for approvaf and file.

AMENDMENTS TO PRE-TRIAL ORDER

l,oteosrrroN oF TERREN1E D. suLLrvAN taken 5/26/g2

inteosrrroN oF GERRy FARMER coHEN taken 5/25/82

,DEPOSITION OF JOHN L. SAI/DERS taken 2/23/83

DEPOSITION OF SENATOR I4ARSHALL RAIJCH taken 2/24/83

'oEposrrroN oF wrLLrAM D1NALD MrLr,s taken 2/23/83

:. DtpasITIoN oF DANTEL T. LTLLEY taken 2/24/53

AL - CAS. to

,State of N.C.

I:,IOTION TO INTERVENE AS A PLFF. by pugh plff - w/cs.

lJorrcE of l'lotion Hearing for 7/25/83 by pugh plff. re: mot. to intervene

roPPosrrroN To TAKTNG oF DEposrrroll - p1ff. objects to the taking of c. B.

, w/cs.

Conies of entrres 117-119 to Danet.

jrtt

cgw i

- ,7cs.

I

Hauser -l

c7n.

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

PLAINTIFF

R-\LPH GINGLES, ei al.

DEFENDANT

RUFUS EDMISTEN, et al.

DC lllA

(Rev. 1,.75)

li /zz / st

I

I

PLAINTIFF

RALPH GI\GLES, et a1.

DATE

i

NR-

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

HOIVARD CLEI{ENT, III taken on 7/21/83 in

in 81-1066-CIV-5 and 82-545-CIV-5.

io

@

l4.ao.70M

DEFENDANT

RUFUS EDIIISTEN, erc., el a1.

PROCEEDINGS

ORDER - previ-ous orcier of consolidation of this case(pugh vs. Hunt, gI-1066-5)

ru/Gingles case is withdrar,rn and the trial of this "u"" ,/ cingtes caseis continued. This order is entered rvithout prej. to right of pltfs. to

move to intervene in Gingles, and if a1lorued, to prosecute all their

claims upon Erial of Gingles case rvhich are consonant w/claims at issue

in this case. (DUPREE, J.) (crv.0.B.#70, p. 160) cys. ro be served by

J. Dupree 7l25l33 A.11. i-n -open court. (This order captioned for pugh

case,81-1066-CIV-5) jj

ORDER - mot. of Alan V. Pugh, Gregoiy T. Griffin, )Iason llcCu11ough, paul B.

Eaglin' Ethel R. TroEter, Gilbert Lee Boger, David D. Almond, Jr., Ray

I'larren and Joe B. Roberts to intervene as parties plaintiffs in this

action is a11orved. (DUPREE, J.) (CIV.O.B.il7O, p. 161) cys. ro be

served by J. Dupree 7/25/83 A.ll. in open courr. ]J

APPEilDrx ro DEFTS' P-T BRrEF - w/cs & attach.ments. cy. to panel. cgw

APPLICATION BY DEFTS. TO USE DEPOS. OF I,IITNE-qS AT TRIAL - w/cs. Cy. to panel. cgr.r

IORDER - this ct's order of 7/22/83, is amended to reflect that only the motion of

I olason l'lccul1ough, PauI B. Eaglin & Joe B. Roberts to intervene as

I

i parties pIff. in this action is allowed. (CIV O.B. #70, p. 2j,7)

I fDupree, J.) CC to cor:nsel by Court. csw

ergn,

7/2s/83

7 /26/ 83

7 /2e /83

a/ 3/83

I DE?OSITION OF

I

I

I osposrrroN

I

A. J.

for use

Raleigh, N.C. Al-so

Also for use

O-R.DER - the following juris. stip. are not pertinent to this cause: 3A, 6A, 68,

5E, 5F, 6G, & 6H. Ttrose stip. are not accepted by the court.

Additionally, excep insofar as they may be pertinent to the Gingles

v. Ed.nisten cause of action, the contentions, list of exhibits, tist

of "vitnesses & designation of pleadings of the Pugh pIffs. are not

accepted by the court. Except as orovided, the P-T order is approve

(CIV O. B. +70 , P. 226 ) (JUDGES PHILLIPS, DUPR]]E, & BRITT) CC tO COrrN-

sel & Panel. cgw

OF THOI.IAS B. HOFELLER taken on 7/22/83 in Raleigh,

i-\ During trial deftsr mot. for a directed verdict was denied.

8/30/83)[ L27,i cPoER. - parties are to submit proposed findings of fact & conclusions of,\-/

126 ( 3b) :,iD:.1O. IN SUPPOP.T OF DEFTS' APPLICATION

Hauser - w/cs. Cy. to Pane1.

TO USE DEPO. AT TRfAL of Charlie Brady

l-lon-Jury Trial began on 7/25/83 before a three-judge court; The Honorable J.

Dickson Phillips, Jy., The Honorable F. T. Dupree, Jr., and The

tlonorabre trI. Earl- Britt. Lesl-j-e J. trIinner, Lani Guinier, Robert

Hunter & Arthur Donaldson for the r:1ffs. a p1ff.-intervenors: Jerris

Leonarc, Kathleen l'lccuan, Tiare smiley, Norma Flarrell & Jim wallace

for the defts. Ti-rne: 8 dalrs or 5r hours. Transcript to be comprete

witnin 5 wks. & counser has 30 days from that time to submit propose

Findings of Fact & Conclusions of Law, along with supporting memos.

A hearing wilr be schedured wj-thin 15 days after said submissions.

or a drrected verdict was denied. cE^/

fi.ndings of fact & conclusions of law, with

i nelno., by lO/7/83, & to key eacn Droposed finding to the correspondin

Ir Page in the record. Closing argr-unents scheduled at IO:00 a.m. on LO/

L4/83 in Ctrn. I, Raleigh, N.C- (DUPFEE, .j.) CC to counsel, J. Britt

DOCKET NO.

PAGE 1I OF

8 1-803-Cr

-

PAGES

& J. Phillips . C7. to :ts. ?odd. cgw

aa

oc lllA

(Rev. 1.'75)

CIVIL OOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

PLAINTIFF

RALPH GINGLES, et aI.

DEFENDANT

RUFUS EDMISTEN, etc., er, al.

DocKEr No gI-903-crv

pace 12 oF

-pAGEsOATE PROCEEOINGS

t7 /83 i I rnallscnrPT of rrial before J. Phi1lips, J. Dupree & J Britt

I r,rlrr ?( - 983 - Vols 1-8. Jo Bush CT. R

lTranscipts mailed to J Phillips Voluae.s1-8

Nn. I

i

held

tr.

in Raleigh

3 Judges.

| 129(3b) PoST-TRTAL r'{E}IORANDIrM 0F PT/INTIFFS

t--z--.., i slip opinions. & cs. Cys. 3

ET AL. -wl Appendix of

araEe blue folder)

RALPH

Judges

GINGLES,

. (in se

to/24/83

L/2U83

tr/ 30/83

12/ s /8s

L2 /8183

1/27 /84

1A

- \r/ cs . uy. ges.

(in separate green folde'r.

b) DEFENDANTS'POST-TRIAL BRIEF - w/cs. Cy. 3 Judges. (in separare green folder.) j

i rinal Arguments heard before 3-judge pane1. reslie J. winner & Lani Guiner for

I, the plffs.; Jerris Leonard, Kathleen Henan & Jim Wallace for the

i defts. Time: 2 hrs. Counsel to submit supple. brief within I0

Ii days & to limit it to 5 pages. caw

132(3b) SUPPLEI'{ENT TO PLAINTIFFST POST_TRIAL MEI{OMNDUM - by I1tf. w/cs.Cy. J. Phillip133(3b) DEFENDANTST POSr-TRTAL Mm{oRANDIIM rN RESpoNSE To couRT's oRDnn oF ocroBER 14,I

,a\i 1983 - w/cs. Cy. J. Phil1ips, Britt, Dupree.

qy

I

MorroN To CoNSTDER ADDTTToNAL EVTDENCE by plff. - w/cs & exhibirs. cgw

) ----, i cy. to 3-judge panel.

i(, loerts! RESPoNS:"T_::::1"-III:

'o^.:o*::':*]1::l'I:I1: "u,oENcE

- no objecrion -v I p/cs &a.ttaoh*ren*c- Cy. to 3-judge panel. cgwI

136(3b) DEFTS' MEMo. rN suppoRT oF DEFTs'! RESpoNsE To PLFFST l.tor. To CoNSTDER

ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE - w/cs & attachments. ca[^,

0RDER - upon consideration of pltfs' motion (to consider additional evidence)and deftstresponse the court allorvs the filing of pltfsr exhibits90, 91 and 92 and defts' exhibits 6s, 66 and 67. The court rvillconsider these exhi-bits to the extent that they are found to berelevant and otherrvise admissible in evidence. The rnotion of pltfs.for leave to file additional exhibits rerating to post-trial electionsheld in jurisdictions other than Nlecklenburq dounty is denied.(DUPREE' J') (civ'o'B'-!l?.' !-: -61). cy. to counsel, J. Britt G, J. phiir

PLATNTTFFST OBJECTToN To DEFENDANTS' ExHrBrrs 65, 66 and oi--"7"".--cy. dati"l. "-::

MEMORANDUM OPINION of j-Judge Panel- - Phil7ips, Cir.Judge, Britt, Chief Dist.Judge

& Duptee, Sr. Djst.Judge. (the Court) having determined that the

i

state's redistricting pIans, in the respects chaTTenged, are not in cor.

pliance w/the mandate of amended 52 of the Voting Rights Act, the cour.

wiLT enter order decJaring redistricting pTan vioLative of S2 in those

respect.s, & enjoining defts. from conducting eLections pursuant to the

plan in Lts pre.sent form. -------/r'ew plan to be submitted bq 3/16/84---

ORDER - Adjudged & Ordered that: 1. Chapters 7 e 2 of N.C. Ses. Iaws of 2nd Extrat

Sess:.on of '82 ('82 redistricting Pl-an) are decLared to vioLate sec.2 ,

of the Voting Rts. Act. of 7965, -----bg creation of folTowing TegisTa-

tive distrr.cts: ,Senate Dr.st. No.s. 2 e 22 ,House of Rep.Dist./Vos. 8,2L,

23,36 & 39. 2. Pending further orders, defts., their agents, etc. are',

enjoined from dconducting ang primarg or gen.elections to efect memberi

of State,Senate or State house of Rep. to repre.sent, inter aLia, regis.

tered bTack voters resid'ent in ang areas now inclued w/n leg.disxs.

iidentified in par.7. of this Order, whether pur.to'83 redist.plant ot,

ang revised or new plan. ----Jurisdiction of court retained to entertaj

su.bmjssron of revised Teg.districting pLan bg defts., or to enter

I

further renediaL decree, in accordance w/Memo.Opinion.-- Awatd of cost:

& atcas. fees praged for p7ffs. is deferred pending entrg of a final

juCAmenc---. Phillips, Cit.Judge, Britt, Chief Disc.Judge & Dupree, Sr.

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

D oc KEr ruo. 8-1:_EQ!:!_l

PAGEI3 oF

-PAGES

c l11A

r'ev. 1 75)

PLAINTIFF

P'r\LPfl GINGLES, et al

D EFEN DANT

RTIFUS EDIII}JSTE}], et a1

DATE

i

2/s/84

:/s/84

t/L0/84

F'ILE ii4

2122184

3/07 /84

i/L6/84

3/75/84

3/19/84

)3 /20 /8411

)41 24184

,l02l84

)/08/84

o

i@

@

I

,

z-\'.

fts7

\-/ i

143 (5

144 (3

PROCEEDINGS

NOTICE OF APPEAL TO T}IE SUPREIIIE COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Cy. to Judges Phi11ips, Bri-tt F, Dupree.

- by defts. - rv/cs.

I10TI0N T0 srAY ORDER AND IlrJUl,lcrION PENDING AppEAL - tr;-riefts. _ w/cs.

C),. to Judges Phi11ips, Britt Q Dupree.

) I\IE\IORANDUIU 0F lAitr(in support of motion to stay order and injunction pending

appeal) - by defts. - rvlcs. - Cy. to Judges phi11ips, giitt E, Dupree. '

) PLAINTIFFS' IIE)IOMNDU,I II OPPOSITiON TO DEFENDANTS' JUOTIOi{ TO STAY ORDER AND

INJUNCTI0\ PENDING AppEAL - islcs. €r atrached Exhibits A_E.

ORDER - i3y unanimous decision of the tourt, the motion for a stay is denied.(BRITT,J.)(Ciy.Q.B.#72,p...334).Cy.t9CqunSe1.

llailed cy. of Notice of Appeal to'Mr. Alexan'der-L. -SEiina6, C1erk, Supreme Courr

of U. S. including Motion to Stay and Injunction and Memorandum of Law

in Support. Copies of order appealed from per request of Clerk and Mem.

ac

0p inion. jrj

ERRATA T0 TR-A.i\scRrPT - by atty. for pltf . To be arrached to rranscript jrj

Received order from the Supreme Court of the United States denying the applicatio

for sray of the Mandate of the US District Court (EDNC). SCUS//A-653. jrj

IIOTION AND SUBI1ISSION PURSUANT T0 COURT'S ORDER AND JUDGMENT OF L/27184 w/ atchs.

CYS. to Panel. jrj

Iliscellaneous pages from Exhibits 93 and 95 either missing or illegible filed to

be substituted or lncluded with motion and submission attachments filed on

03/13/84 Item ii747. Cys. to Judge Britt and Judge Dupree. Judge Phillips

served by mail by plantiffs' counsel. jrj

PLA"\TIFFS' PRELI}IIi{ARY RESPONSE TO DEFENDANTSI SUBMISSION; MOTION FOR LEAVE TO TAK

DEPOSITIONS; REQUEST FOR EVIDENTIAPJ HEARING - by p1tf. Cy to 3 Judge panel

filed cy. to pltffs' counsel. jrj

ORDER - thaE the motibns by the pltffs Eo take depositions and for an evidentiary

hearing are denled. (BRITT) CIV0B/|73, p.97. CC to Pane1, counsel. jrj

SUPPLE)IENTAL SUB)IISSION - by defendants. CC to Panel. jrj

ORDER - thaE the redistricting plan adopted by the general assembly is approved

insofar as it. redistricEs former house districts 21, 23,36, and 39 and

Senate districts 22 and the injunction is disolved and jur:isdiction is re-

E.ained in rhj.s courtfor $uch further proceedings as may be required. (Phi11

Circuit Judge) Brict, and Dupree, JJ. concurring. CIV OB //73, p. 242. jrj

SUPPLE)IENTAL OPINI0N - by judge Phillips jrj

IIOTION - by defendants for approval of state legislaEive districts and the holdin

of elecEions JuIy 17, 1984 jrj

ORDER - (1) that Ehe legislarive redistricting plan adopted by the General Assemb

on 3/8/84 and submirred by the defendanrs is APPRovED; (2) thar the injunc

entered by this Court is DISSOLVED; (3) that the holding of elections in

those disEricts on July 17, 1984, id APPR0VED; and (4) JurisdicEion is

retained for such proceedings as may be required. trlith concurrences of

Phi11ips, Circuit Judge and Britt, Chief District Judge. (DUPREE) CIV OB

73, p.343. CC to Counsel. jrj

RECEIVID LETTER FROY JUSTICT DEPARIIEIT (COPY) - re: more informaEion on liouse

and Senate Districts. Cys. ro panel. jrj

v

ior

j /14 /3t+

\, .l

oc llr.A

(Rev. l/75)

r0/ 04/ 84

Lo / 04 /84

L0/LU84

L0 / 22/ 84

r0/L9/84

L0/29184

LO/30/84

t2/ 2Ll 84

t2l 27 I 84

CIVIL DOCKET CONTINUATION SHEET

FURTHER RELTEF - by plrffs. Notified that panel and parties served

by pltffs. counsel. Filed cy. to pltffrs atty.

IN SUPPORTH OF MOTION FOR FURTHER RELIEF - by plrffs. jrj

OF SHELLY WILLINGHAM, GI K. BUTTERFIELD, JR.,MILTON F. FINCH,JR., AND

THOMAS L. WATKER rN suPPoRT 0F PLATNTTFF'S - by pltff. cys. ro panefiled cy to pltffrs atty in I'unstamped envelope. jrj

RESPONSE TO PLTFF'S MOTTON FOR FUR.THER RELTEF AND MEMOMNDLM rN OpposrTroN - bydefts. (one document) Cys. served on panel by Atty. Gen'1 Office.

}IOTION FOR

) lrrlroRanoulr

AFFIDAVITS

(exhibits attached).

INFOR}IATION LETTER FROI'I VOTING RIGHTS SECTION OF US

panel.

JUSTICE DEPARTMENT - "y".

J#

jrj

jrj

Jr

Jr

jr

jrj

an unaffilliat

State Board of

r60

161

) supplErtENTAr IIEIIoRANDITM rN suppoRT oF MorroN FoR FURTHER RELTEF - by plrff's.

Filed cy. Eo Judge Dupree, Britt, and pltff. Platff served Judge

Phillips and defendants, counsel by express mai1.

SUBUISSION OF DEFENDANTS' EXHIBIT 88 - bY dCfENdANES. CC EO PANCI.

ORDER - that Ehe parties are ORDERED to;submit to the Court not later than 5:00

22 October 1984, aproposed interim redistricting plan and election

and election schedule which sahall provide for (a) four single membe

disEricts; and (U) a general elcetion to held not late 31 January 19

CIVOB/F 75, p. 238. CC to Panel (nnttt, .t. for rhe Court) and counse

16 RESPONSE TO ORDER 0F OCTOBER 11, 1984 - by pltffs. Cys. to panel.

RESPONSE T0 ORDER 0F OCTOBERII, 1984 - by defrs. Cys. ro panel.

Letter from pltffrs atty.

@

@

lrl

ORDER - that the House DistricE Formerly composed of Edgecomb, Nash, and Wilson

Counties be reconsEituted inEo 4 single member districts, that defts

conduct elections for the purpose of electing one RepresentaEive f

each district, that said elections be conducted acoording to the fol

schedule LLl2 - formal legal notice of election, lL/9 - filing peri

LL/L6 - filing period closes, lL/26 to 12/11 - AbssnEee voring, 12/l

First Primary, L/8 - Second primary as needed, and ll/29 - General

Election. and finally, Ehe represenEatives so elected shall serve th

same terms as those elected on Nov. 6, 1984. so ordered. (nRttr ror

court) crvon lf 75, p. 301. cys. to parEies and counsel of record. j

JorNT llOTroN 0F PLTFF's AND DEFTS'S - cys. ro Three Judge panel.

ORDER - ThAT orders Ehat any person who wishes Eo run as

in the general election shall petition the

on or before l/15/85. CIVOB /l

Ehe CourE

cand idaEe

Elec t ions

PLAINTIFF

PII GING

DEFENDANT

DOCKET NO.

pace lbr

81-803-c

oArE | "* |

PROCEEOINGS

05 /22 /85'l ORDER OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE US - Ehac the statemenE of jurisdiction in this

in this case having been submitted and considered by this Court, in

t.his case pobable jurisdiction is noted, timited to Questions I and

resented by the statemenE as ro jurisdiction. (APRIL 29, 1985). jr

)s / 2r/ 8416D

| ,ru<'

oe/ 27 /84i@u9/tU64trLtt

lL-.--l

I

L-..

09 / 27 / 84 l/ rs})l\-/

I

L0/03/84

r59(U

04/30/8s

I

TMNSCRIPT OF CLOS ING ARGU}IENT OF I"lR. LEONARD BEFORE 3 JUDGE PANEL - Caten

Jo Bush Court Reporter.

}IAILED RECORD ON APPEAL TO US

Cpys. to counse1

SUPREME COURT -

& Judges.

consisting of 11 volumes. vl Index

ele

26 85