Ellhamer v. Wilson Brief of Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

December 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ellhamer v. Wilson Brief of Amici Curiae, 1970. b3f96dc3-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3f85a9c9-e855-413d-910d-d57f080cacda/ellhamer-v-wilson-brief-of-amici-curiae. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

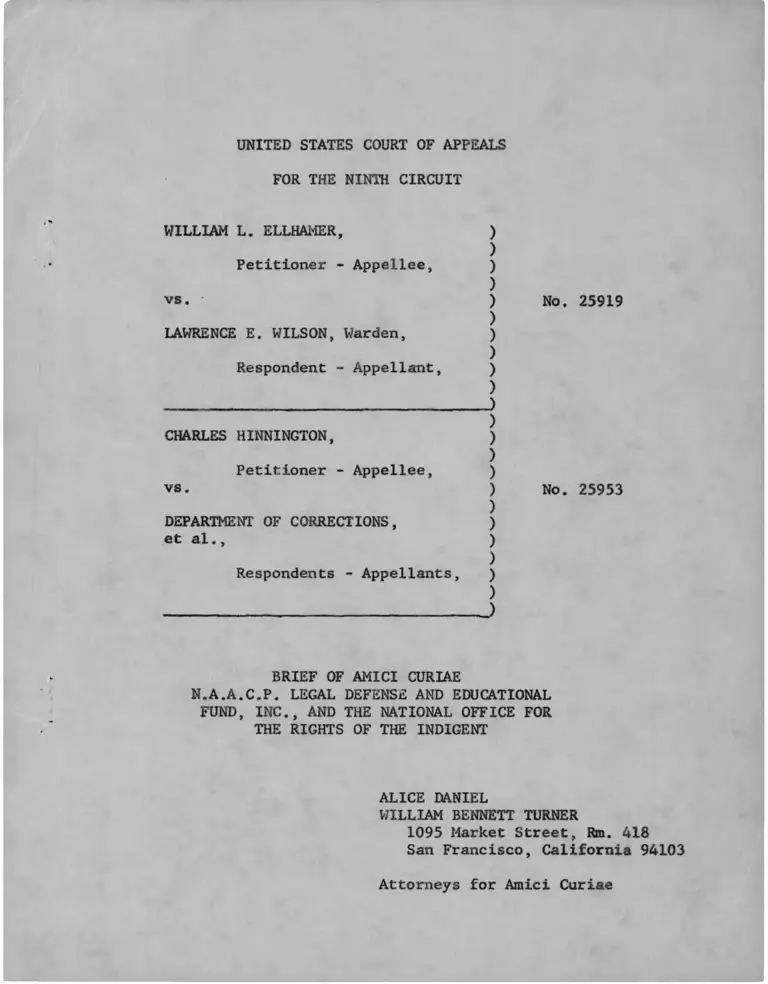

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

WILLIAM L. ELLHAMER, )

)Petitioner - Appellee, )

)vs. )

)LAWRENCE E. WILSON, Warden, )

)Respondent - Appellant, )

)

_____________________________________________________ )

)CHARLES HINNINGTON, )

)Petitioner - Appellee, )

vs. )

)DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, )

et al., )

)Respondents - Appellants, )

)

_________________________________________ .)

No, 25919

No. 25953

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AND THE NATIONAL OFFICE FOR

THE RIGHTS OF THE INDIGENT

ALICE DANIEL

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

1095 Market Street, Rm. 418

San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

INDEY

Page

STATEMENT 0? THE INTEREST OF Tip., AMICI

CURIAE ............................ ....... 1

ARGUMENT

THE STATE MAY NOT TERMINATE A

PAROLEE'S LIBERTY AND ORDER HIS RE

TURN TO PRISON WITHOUT OBSERVING

MINIMAL SAFEGUARDS REQUIRED BY DUE

PROCESS............ ................... 4

CONCLUSION 26

TABLE OF CASES

P.a_£.e„

In re Allen

78 Cal. Rptr. 207, 455 P.2d 143 (1969) 10

Ashworth v. United States

391 F.2d 245 (6th Cir. 1968) 14

Baxstrom v . Hero Id

• 383 U.S. 107 (1966) 20

Blea v. Cox

75 N.M. 265, 403 P.2d 701 (1965) 13

In re Brown

67 Cal. 2d 339, 62 Cal. Rptr. 6, 431

P .2d 630 (1967) 6

Carothers v. Follette

314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D.N.Y. 1970) 2,20

Chewning v. Cunningham

36S U.S. 443 (1962) 18

Commonwe a11h v . T in s o n

433 Pa. 328, 249 Atl. 2d 549 (1959) 12

Escalera v. New York City Housing Authority

425 F .2d 853 (2d Cir. 1970) 15, 16

Fleming v. Tate

156 F.2d 848 (D.C. Cir. 1946) 25

Fortune Society v. McGinnis

70 Civ. 4370 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 24, 1970) 2

l

In re Gault

387 U.S. 1 (1967) 17

Gilmore v. Lynch

No. 45878 (N.D.Cal. May 28, 1970) 17

Goldberg v. Kelly

397 U.S. 254 (1970) 4,5,14,16,22,23

Greene v. McElroy

360 U.S. 474 (1959) 14,16

In re Hall

63 Cal. 2d 115, 45 Cal. Rptr. 133, 403

P.2d 389 (1965) 10

Hannah v. Larche

363 U.S. 420 (1969) 5

Hewitt v. North Carolina

415 F.2d 1316 (4th Cir. 1969) 13

Holt v.'Server

309 F.Supp. 362 (E.D. Ark. 1970) 2

Ex Parte Hoopsick

172 Pa. Super. 12, 91 A.2d 241 (1952) 15

Hyland v. Pro cunier

311 F.Supp. 749 (N.D.Cal. 1970) 10,17

Jackson v. Godwin

400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1968) 2

Johnson v. Avery

393 U.S. 483 (1969) 19

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath

341 U.S. 123 (1951) 16

ii

20

In re Jones

57 Cal. 2d 860, 22 Cal. Rptr. 478,'

372 P.2d 310 (1962)

Kent v. United States

383 U.S. 541 (1966) 13,15

Love v. Fit2harris

311 F. Supp. 702 (N.D. Cal.. 1970) 10

In re McClain

55 Cal. 2d 78, 9 Cal, ‘Rptr.. 824, 357

P.2d 1086 (1960), cert, denied, 368 U.S.

10 (1968) 9, 10

Me Connell v. Rhay

393 U.S. 2 (1968) 11

Mead v. California Adult Authority

415 F .2d 767 (9th Cir. 1969) 10

Mempa v. Rhay

389 U.S. 128 (1967) 11

Menechino v . 0swald

430 F.2d 403 (2d Cir. 1970) 6

Morris v. Travisono

310 F. Supp. 857 (D.R.I. 1970) 2,20

Mosher v. LaVallee

No. 67 CV 174 (N.D.N.Y. July 31, 1970) 2

In re Narcotic Addiction Control

Commis s ion v. James

22 N.Y. 2d 545, 293 N.Y.S. 2d 531, 240

N.E. 2d 29 (1968) 22 .

Nolan v. Scafati

430 F.2d 548 (1st Cir. 1970) 20

iii

15

North Carolina v. Fear

395 U.S. 711 (1968)

In re O ’Malley

101 Cal. App. 2d 80, 224 P.2d 83 (1950) 10

Oyler v. Boles

368 U.S. 448 (1962) 18

Palmigiano v. Affleck

Nos. 4296 and 4349 (D.R.I. Aug. 24, 1970) 2

In re Payton

28 Cal. 2d 194, 169 P.2d 361 (1946) 5

People v. Dominguez

256 Cal. App. 2d 623, 64 Cal. Rptr. 290

(1969) 10

People v. Hernandez

229 Cal. App. 2d 143, 40 Cal. Rptr. 100

(1964) . 10, 17

People v. Martinez

1 Cal. 3d 641, 83 Cal. Rptr. 382, 463

P .2d 734 (1970) 10,15

Perry v. Williard

247 Ore. 145, 427 P.2d 1020 (1957) 13

Pointer v. Texas

380 U.S. 400 (1965) 14

Rose v. Haskins

383 F.2d 91, 97 (6th Cir. 1968) 17

Schuster v. Herold

410 F:2d 1071-(2d Cir. ), cert, denied,

396 U.S. 847 (1969) 20

Shapiro v« Thompson

. 394 U .S. 618 (1969) ... ' 16,23

Shone v. State of Maine

-406 F.2d 844 (1st Cir.)vacated as moot

396 U.S. 6 (1969) 20

Sniadach v ..Family Finance Corp.

395 U.S. 337 (1969) 22

Sostre v. Rockefeller

312 F.Sapp. 863 (S.D.N.Y. 1970) 20

Specht Vo Patterson

386 U.S. 605 (1967) 17,18,19

State v. Pohlabel

61 N.J. Super. 242, 160 A.2d 647

(App. Div. 1960) 15

Townsend v. Burke

334 U.S. 736 (1948) 15

United States ex reL Gerchman v. Maroney

355 F.2d 302 (3rd Cir. 1966) 18

United States v. Wade

388 U.S. 218 (1967) 12

In re Winship

397 U.S. 358 (1970) 17

Wright v. MeMann

387 F.2d 519 (2d Cir. 1967) 19

v

OTHER AUTH0R.IT IES

Pass

4 Attorney General's Survey on Release

Procedure (1939) 9

Bates, Probation and Parole as Elements in

Crime Prevention, 1 Law &. Contem. Prob. 484

(1934) 24

California Adult Authority Policy Statement

No. 6 11/1/57 7

California Assembly Committee on Criminal

Procedure, Deterrent Effects of Criminal

Sanctions (1968) 23

California Criminal Law Practice (Coat. Ed.

Bar. 1969) 22

Parole Status and the Privilege Concept,

1.969 Duke L.J. 139 17

Progress Report. 1967-1968, California Depart

ment of Corrections 6,8

Van Alstyne, The Demise of the Privilege-

Right Distinction in Constitutional Law, 81

Harv. L. Rev. 1439 (1968) 16

vi

STATEMENT OF THE INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. is a non-profit corporation formed under the

laws of the State of New York in 1939. The Fund was

incorporated to assist black people to secure their

constitutional rights by the prosecution of lawsuits.

Under its charter, one of its purposes is to pro

vide free legal assistance to Negroes who suffer in

justice because of race and who are unable, on account

of poverty, to employ legal counsel.—^

A central purpose of the Fund is the legal

eradication of practices in our society that bear with

discriminatory harshness upon blade people and upon the

poor, deprived and friendless, who too often are black.

To further this purpose, the Fund in 1967 established

a separate corporation, the National Office for the

Rights of the Indigent (N.O.R.I.), having among its

objectives the provision of legal representation to the

poor in individual cases and the advocacy before appell

ate courts of changes in legal doctrines which unjustly

affect the poor.

1/The Fund's charter was approved by a New York court,

authorizing the organization to serve as a legal aid

society. It is entirely independent of other organiza

tions, and is supported by- contributions from the public

1

In 1970 the Fund received a foundation grant

for the purpose of promoting efforts toward penal

reform. The grant contemplates that the Fund will do

research to identify the most serious and fundament

al problems in corrections and, where appropriate, will

bring test litigation or suggest administrative or

legislative reform.

The Fund has been involved in several impor- ̂ ' *

tant prison cases in several different states, includ

ing Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1968);

Carothers v._Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D.N.Y. 1970);

Mosher _v. LaVallee, No. 67 CM 174 (N.D.N.Y. July 31,

1970); Holt v . Sarver, 309 F.Supp. 362 (E.D. Ark. 1970);

Morris v . Travisono, 310 F.Supp. 857 (D.R.I. 1970);

Palmlgiano v . Affleck, Nos. 4296 and 4349 (D.R.I. Aug. 24,

1970); Fortune Society v. McGinnis, 70 Civ. 4370 (S.D.

N.Y. Nov. 24, 1970). The issues presented in these cases

cover a broad spectrum of the difficulties faced by

prisoners in realizing their fundamental rights as

American citizens.

The unifying purpose of the Fund's lawsuits has

been not only elimination of the most barbaric and out

moded conditions of prison life, but also implementation

of the rule of law in the corrections phase of the

criminal process» We believe that if the lawbreaker is to be

2

rehabilitated, he must be convinced of -the validity

of our legal system. Because his attitude toward

- society after release from prison will be shaped by

his experience with its representatives who administer

the penal system, minimal standards of fairness should

be observed in every phase of the correctional process.

In short, we believe that prison officials, like all

# # j * Vpublic officials, should be accountable to principles

of law. We believe that the decision below in this

case will further this aim, and that the decision, is a

sound balance of the realities of parole and considera

tions of public policy.

3

ARGUMENT

THE STATE MAY NUT TERMINATE A

AMD ORDER HIS RETURN TO PRISON

MINIMAL SAFEGUARDS REQUIRED BY

PAROLEE!S LIBERTY'

WII ROUT OBSERVING

DUE PROCESS.

The decision to suspend parole has critically

important consequences for the parolee. It means

that lie will be removed from his community, family

and work, and returned to prison for an indetermin

ate but certainly substantial period of time. It

would seem fairly obvious that a decision of such

moment, depriving an individual of his liberty, should

be made in a formalized proceeding which gives some

assurance that the factual basis for suspension was

arrived at fairly and accurately; and indeed, it is now

clear that the Constitution requires no less.

In Goldberg v. K elly, 397U.S. 254, (1970), the

Supreme Court held that minimal procedural safeguards

are constitutionally required whenever the state proposes

to act in a way which will adversely affect an impor

tant individual interest. The extent to which procedur

al due process must be observed is influenced by the

extent to which the individual may be "condemned to

suffer grievous loss" by the government action, and whether

the individual's interest in avoiding that loss out

weighs the governmental interest in summary, adjudication.

4

Which procedural safeguard's ' are. necessary is deter

mined by the precise nature, of the governmental

function involved and of the private interest that

has been affected by the governmental action.

Goldberg v. Kelly, supra; Hannah v. Larche, 363 U.S,

420, 442 (i960).

Analysis of the governmental function involved

in parole suspension and of the individual's interest

in retaining his status compels the conclusion that

essential procedural due process safeguards should he

observed at parole suspension proceedings.

The Nature Of The Governmental Function Performed

The primary function performed at a California

parole suspension hearing is to make the factual deter

mination that "good cause" for suspension exists,

since suspension without cause is prohibited by Section

3063 of the California Penal Code. In the usual case,

the statute is satisfied by a finding that the parolee

violated one or more of the conditions of parole. In

re Payton, 23 Cal. 2d 194, 169 P.2d 361 (1946). Having

made the initial determination that a violation occurre

the Board is then authorized to go on and consider a

variety of other factors before it decides, as a discre

tionary matter, whether return to prison is

5

o /warranted

In making, the determine. .ion that "good cause"

for suspension exists, the Adult: Authority is fre

quently called upon to resolve disputed questions of

fact. When the parolee has been convicted of a

crime committed while on parole, there may be little

dispute about the facts but even then, lack of

finality in the criminal conviction may warrant takingo f

evidence on the underlying facts.—

Department of Corrections statistics show that

small percentage of parolees are returned to

because of new felony crimes.

only a

prison

2/The need to make a factual determination as the pre

dicate for further action distinguishes parole revoca

tion proceedings from parole release decisions, where

procedural due process may be less necessary because

no existing interest is jeopardized by charges of mis

conduct and no findings are required. Cf. Menechino v.

Oswald, 430 F.2d 403 (2d Cir. 1970).

3/California law prohibits revoking parole on the basis

of an invalid conviction. In re Brown, 67 Cal. 2d 339,

62 Cal. Rptr. 6, 431 P.,2d 630 (1967)7

4/For men released in 1965 the return rate was 38.3 per

cent, with only 14.9 per cent returned with new felony

crimes. Of those released in 1966, 17.1 per cent were

returned to prison, including only 5.6 per cent with

new felony crimes. Of the 1968 releases, 15.7 per cent

were returned, including 4.11 per cent with new felony

convictions. (Progress Report 1967-1968, California

Department of Corrections).

6

The majority of parole suspensions are based on

alleged misconduct for which the paro.lee was never

tried; and in such cases the need foi procedural

regularity is much greater because the facts are more

often in dispute.

California Adult Authority Policy Statement

No. 6 (11/1/57) [Appendix A, infra] authorizes

suspension at the district attorney's request, on

the basis of criminal allegations which the parolee

denies. This procedure gives the prosecutor's case

the effect of, and even more finality than a

criminal conviction (which might be reversed on

appeal). The district attorney is given the power to

effect a parolee's return to prison on the basis of

charges which have never been subjected to the scru

tiny of a magistrate or grand jury. No judicial

officer ever reviews the prosecutor's evidence to

see whether even a prima facie case could be proved;

and yet the parolee is denied all the procedural safe-*

guards he would have received had the prosecution been

forced to put its case to trial.

Most parole suspensions are based on non-criminal

acts which are alleged to violate the conditions of

parole. Many of the conditions are extremely broad and

general, such as the prohibition against "association

7

with individuals of bad reputation"; (Condition 8,

California Parole Agreement, App. Br.'Appendix "i")

or the requirement to conduct oneself "as a good

citizen." (Condition 12)

■ The very nature of the charges on which most

parole suspensions are based makes it inevitable

that there will frequently be. dispute about the under

lying facts. The basic'question of whether the

parolee performed the acts claimed to violate the

agreement is decided by the parole agent's written

report, which is given conclusive weight. Yet these

reports are not even based on the agent's firsthand

knowledge of the circumstances. Parole agents have

large caseloads, averaging 70-80 parolees (Progress

Report 1967-1968), and it is impossible for an agent

to have personal knowledge of the activities of all

his parolees. In preparing his report,the agent

relies on hearsay and rumor gathered from sources of

unproven reliability, without necessarily investiga

ting either the basis for his informant's information

or his motives in relaying it. Even when the parolee

is charged, with a specific act such as drinking in

violation of Condition 5B (which prohibits consump

tion of any alcoholic beverage), it must be recognized

that the agent's report is usually based on hearsay,

since a parolee would rarely drink in the presence of

It should be noted that parole suspension

and revocation is based on a written report. The

agent is not present at the hearing to answer ques

tions or explain the bases for his assertions. Even

when the report contains firsthand knowledge, there

is rio guarantee of fairness. Some of the parole

conditions, such as the onerequiring cooperation with

the parole agent (Condition 10) are susceptible to

highly subjective interpretation. Parole agents are

human and it is possible that friction between the

agent and the parolee may have influenced the agent's

judgment.^ Since the parole agent is not present for

questioning about his report, there is no way for the

fact-finder to judge the reliability of his perceptions

and interpretations, cr to make sure that they are un

colored by bias.

Substantive Limitations on State Action

There are important substantive limitations on

the Adult Authority's power to suspend or revoke parole.

In addition to the basic requirement that good cause be

shown, which bars the Authority from acting on the basis

of "whim, caprice or rumor", In re McClain, .55 Cal. 2d

5/S’ee 4 Attorney General's Survey on Release Procedure

'246-7 (1939).

his agent.

- 9 ~

78, 9 Cal. Rptr. 824

dended, 368 U.S. 10

ed in the absence of

,'357 P.2d 1086 (1960), cert.

(1968), revocation is prohibit-

"substantial evidence" that a

violation occurred. In f_e O’Malley, 101 Cal'. App. 2d

80, 224 P.2d 88 (1950). An invalid criminal convic

tion will not support revocation. In re Hall, 63 Cal.“78 T ----- .2d 115, 45 Cal. Rptr. 133, 403 P.2d/(1965); nor will

proof that the parolee violated an unconstitutional

parole condition. See Mead v . California Adult

Authority, 415 F.2d 767 (9th Cir. 1969). See also

Love v. Fitzharris, 311 F.Supp. 702 (N.D. Cal. 1970),

(ex post facto prohibition); Hyland v. Procunier. 311

F.Supp. 749 (N.D. Cal. 1970) (First Amendment).

The notion that parole is an act of grace,

revocable without regard to constitutional limitations

on state action has been specifically rejected by

the California, courts. See People v. Martinez, 1 Cal.

3d 641, 83 Cal. Rptr. 382, 463 P.2d 734 (1970);

People v. Hernandez, 229 Cal. App. 2d 143, 40 Cal.

Rptr. 100 (1964). See also In re Allen, 78 Cal. Rptr.

207, 455 P.2d 143 (1969); People v. Dominguez, 256

Cal. App. 2d 623, 64 Cal. Rotr. 290 (1969).

Although the legality of the Adult Authority's

decision to suspend parole depends on the accuracy of

10

its factual determination that a violation has

occurred and its observance of substanfive limita

tions on what evidence may be relied on in making

that determination, present procedures are entirely

inadequate to provide an}7 confidence in the relia

bility of the Authority's findings.

The Hight To Representation 3?y Counsel

We wholeheartedly endorse the decision of

the court below, which.held that, at a minimum, the

presence of counsel is constitutionally required at

the time when the state proposes to curtail a parolee's

liberty and return him to prison.

The court below compared the nature and effect

of a California parole suspension proceeding with a

Washington probation revocation, and held that the

decisions in McConnell v. Rhay, 393 U.S, 2 (1968) and

in Msmpa y. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967) require that

a parolee be given the right to representation by

counsel at a suspension hearing. That analysis was

clearly right. Appellant has pointed out that parole

and probation have traditionally been treated in the

same terms (App. Br. p.ll); and we submit that the

essential' similarity between the two leaves no room

for distinguishing Mempa now. Both the parolee and

the probationer have been convicted of a crime by due

process of law and then granted conditional freedom.

11

Although restricted by reasonable regulations,

each has significantly more liberty than he would

have if his "privileged” status were revoked, and each

faces imprisonment as the penalty for violating the

conditions attached to his status.

Quite apart from the question of whether the

Sixth Amendment right to counsel is applicable to

parole suspension proceedings, counsel is required by

due process in order to insure "the integrity of the

fact-finding process" which is the predicate for re

turning the parolee to prison. The decision to sus

pend parole usually rests on allegations of miscon

duct for which the parolee was never tried. The need

to resolve factual issues of this kind is, in itself,

sufficient reason for according the parolee the right

to counsel at suspension hearings. The Supreme Court

of Pennsylvania so held in Commonwealth v._Tinson,

433 Pa. 328, 249 Atl. 2d 549 (1969), in which it said

"...there can be no doubt as to the

value of counsel in developing and pro

bing factual legal situations which, may

determine on which side of the prison

Weills appellant may be residing."—'

6/By his presence alone counsel can enhance the fairness

and reliability of the suspension hearing without

transforming it into an adversarial proceeding. Cf.

United States v. Wade, 383 U.S. 218, 238 (1967).

A number cf other courts have held that tlie need to

make a factual determination dictates the right to

counsel at revocation proceedings, irrespective of

whether sentence is to be imposed. See Hewitt v .

North Carolina, 4.15 F. 2d , 1316, 1322 . (4th Cir. 1969) ;

Perry v. Williard, 247 Ore. 145, 427 P.2d 1020 (1967);

Blea v. Cox, 75 N.M„ 265, 403 P.2d 701 (1965). Cf.

Kent _v̂ United States , 333 U . S . 541, 561 (1966) .-

7/Even if Mempa were to be narrowly read as a "sent

encing" case, it should be applied to this case. The

petitioner in Mempa was sentenced under the provisions

of an Indeterminate Sentence Law which was the model

for the California statute. In California, parole sus

pension automatically fixes the defendant's sentence

at the statutory maximum. In Washington, probation re

vocation has the same effect. In each proceeding, it

must be determined whether the defendant performed a

particular act of misconduct and,then, whether commission

of that act warrants incarceration. In each case counsel

has a vital role to play, first in helping to develop

the underlying facts, and then in supplying information

about mitigating circumstances and the character of the

individual, which/fa'^d to the conclusion that imprison-

ment is unwarranted despite the misconduct.

In both Washington and California, the actual term is

set at a later date following imprisonment; but that

decision may be influenced by the recommendation which

both the California Adult Authority and the Washington

judge are entitled to make. Indeed, counsel could play

an even more effective role eit a parole suspension hear

ing in California than at probation revocation in Wash-

13

Parole suspension affects the most essential

human interest, liberty;' and the legality of sus

pension depends on a determination requiring the re

solution of disputed factual, isues. While we fully

endorse the district court decision, we submit that

in this setting due process requires other procedural

safeguards besides the presence of counsel. We believe

the parolee is also entitled to written notice of the

charges, the right to confront his accusers and the

right to present witnesses on his own behalf. In addi

tion, the decision must rest on articulated reasons

and findings supported by substantial evidence adduced

at the hearing. Goldberg v . Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970);

Greene v.McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 (1959).

Other Essential Procedural Safeguards

When resolution of disputed issues of fact is

required, the rights to confrontation and to present

witnesses are essential. Cf. Pointer v_. Texas, 380

U.S. 400 (1965). It is a denial of due process to use

staff reports of such dubious reliability as the

parole agent's report as the foundation for parole sus

pension, Such reports are not entitled to the benefit

of an "irrebuttable presumption of accuracy" and it is

7/footnote continued

,ington,because.when parole is suspended in California,

the Adult Authority can order the parolee's placement

in a Short Term Return Unit. (See California Criminal

Law Practice (Cent. Ed. Ear 1969) §23.158 p. 605), but

the Washington judge has no such option. Cf. Ashworth

United States, 391 F.2d 245 (6th Cir. 1968).

14

of "critical importance

"examination, critic5srn

" that they be subjected

and refutation"- Kent v.

to

United

States, supra. 383 U.S. at 563 8/

Written findings are essential to insure that

suspension has not been ordered for a constitutionally

impermissible reason and that all the substantive limita

tions discussed above were obeyed. In addition, such

findings eliminate the necessity for holding a full-

scale evidentiary hearing in the event that judicial

review is sought. See North Carolina v. Pearce, 395

U.S. 711 (1968); Kent v . United States, 383 U.S. 541,

561 (1966); Escalera v. New York City Housing Authority,

425 F.2d 853 (2d Cir. 1970); in re_ Martinez, 1 Cal. 3d

641, 83 Cal. Rptr. 382, 463 P.2d 734 (1970).

The adjudicatory nature of a parole suspension

hearing and the enormity of the parolee's Interest in its

outcome clearly show the need for fair and reliable

proceedings. California's summary procedure falls far

short of what is required by due process. The argu

ments advanced by the state to justify its perfunctory

methods will be discussed seriatim. Briefly, the .

8/The fallibility of reports such as these has been

demonstrated in a number of cases in which the court

held that due process had been violated by setting sen

tence on the basis of materially false information con

tained in presentence reports, Townsend v„ Burke, 334

U.S. 736 (1948); State v. Fohla.be!, 61 N.J. Super. 242,

160 A.2d 647 (App. Div. I960); Ex Parte Hoopsick, 172

Pa. Super. 12, 91 A.2d 241 (1952)."

state's theories are as follows: (1) Since parole

has traditionally been treated as a form of grace

rather than as a right, it may be revoked by any

method, however arbitrary, that the state chooses to

employo (2) Due process is unnecessary because a

suspension proceeding is part of the rehabilitative

process and not a .stage in a criminal proceeding.

(3) Having lost his freedom by virtue of a criminal

conviction, an. individual retains no rights which

are entitled to constitutional protection. (4) The

administration of the penal system is exclusively

a state function. None of these arguments is con

vincing.

1• The Right-Privilege Distinction

First, the simplistic right-privilege distinc

tion has been repudiated by the courts in a series of

cases in which its superficiality and inadequacy as an

analytic tool for resolving constitutional questions

affecting important individual interests has been noted.

E .g. Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970); Shapiro v.

Thompson, 394 U.S. 618, 627 n.6 (1969); Greene v. McElroy,

360 U.S. 474 (1959); Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm, v .

McGrath, 341 U.S, 123, 163 (1951)^ Escalera v. New York

City Housing Authority, 425 F.2d 853 (2d Cir. 1970). See

generally Van Alstyne, The Demise of the Privilege-Right

Distinction in Constitutional Law, SI Harv. L. Rev. 1439

(196*8) .

It is now clear that labelling an interest a

16

"privilege" will not foreclose judicial inquiry

into the conditions upon which it is granted or with

held ; and this is true in prison and parole adminis

tration, as in other governmental functions. See Rose v.

Haskins', 383 F.2d 91, 97 (6th Cir. 1968) (Celebrezze,

J. dissenting); Gilmore v. Lynch, No. 45878 (N„D. Cal.

May 28, 1970) (three-judge court); Hyland v. Procurrier,

311 F.Supp. 749 (N.D, Cal. 1970); People v. Hernandez,

229 Cal. Apu. 2d 143, 40 Cal. Rptr. 100 (1964). See

generally Parole Status and The Privilege Concept,

1969 Duke L.J. 139.

2. The Civil-Criminal Distinction

Second, the Supreme Court had repeatedly said

that due process questions are not to be answered by

resort to labels such as "civil" or "criminal". Re

gardless of the label traditionally attached to a pro

ceeding, and irrespective of whether its purpose is

"rehabilitative" or "punitive", the Supreme Court lias

held that it is necessary to focus on the essential

reality of the situation. If, as the result of that

proceeding an individual charged with misconduct may

lose his liberty, due process requires that he be given

all the essential safeguards required by due process.

In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1970); In re Gault, 387

U.S. 1 (1967); Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605

(1967) .

17

81

paquasaad saqnqBqs aqq pun aspoaaduip ao.B suopqsanb aqp

•qoy aqq as pun uipq aa.taq.ues oq 11aopsnI po sqsaaaqup

qsoq aqq oqtl oq ppnoM qp aaqqaqM pus (1oqqqnd aqq

pc saaqutaui oq uiauq Aqqpoq po qBaauq b paqnqqqsuoa,,

quupuapap aqq aaqqaqM appoap oq qanoo aqq paapnbaa

‘uadns ‘wmqoa'ag up paaappsuoa aqnquqs auj, * (8I-ZT *dd

*ag *ddy) ’ sSuqpoaooad ucpsuadsns aqoaud at paquasaad

aan sAbs aquqs aqq souo aqq oq an [quips aau sanssc a.Apq

-Bupiuaaqap/quqq SupAaasqo qqaow sp qp ‘qsapp *aasq 3Apq

-oriop sup 9.re suopspoap qqndoqoAsd qunxas aqx

* (9961 ’ Jt-tO pj-e) 'ZOC

P2'd 99£ ‘ICBuoouh"v aT"vmmqoaao *taa xa sdqiqpaTpup fnaans

‘ uosdaqqnq : a~ q qba cfg • sMnq qqndoqoAsd qunxas aqq Aq

paquasaad pupq aqq po ltouo qnuosaad pun xapdutoou u ao

‘ (6 9 61 ) W *S*n 899 ‘ u^q^upultrio“ TsTIftTuMaqo f (2961 ) 8 ^

• S *n 898 ‘ sa’qd’q TSTaap'^O uuspApppoax st? xpns auo Aqdmqs

AqaApqnqaa n sp sr.ssp m?u. aqq xaqqaqw anaq sp spqx

*ssaooad anp sappspqns qnqq Suppaaooxd n up pauquiaaqap

aq qcnp po sanssp Mau aqq qt?qq saapnbaa uopqnqpqsuoQ

aqq £Suppupp-qonp qBUopqqppB un po spsnq aqq uo quaui

-qspund spq asnaaoup ao aaqqt? oq sasodoad aqnqs aqq pp

‘aixqxo n po paqopAUoo Aq np uaaq snq uosaad b aoqpn

uaAq ‘uopqapAuoo quupurpao e Aq paqpapaaop qou sp aoun

-qacdmp qnqpA po suopqsanb po uopqB'upiuaaqap aqq up ssao

-dad anp qBunpaooxd oq qqdpa s t qBnppAppup aqq,

xxopqopAuoo pBupmpoo b a/vpAong sqqSp^f pbuotqnqpqsuoo' * £

no definite criteria for answering them. The sentenc

ing court had a wide discretion to consider a variety

of factors in reaching its decision. Yet the subtlety

of the issues to be decided was not seen as a reason

why procedural due process could be dispensed with.; nor

was the fact that the court acknowledged the partial].}’

rehabilitative goal of the statute. Parenthetically,

it may be observed that commitment under the sexual

psychopath law, for a period of one day to life, did not

necessarily require incarceration for longer than the

sentence which would otherwise have been imposed for

the crime of which the defendant had been convicted.

Finally, as indicated above, the Supreme Court's decision

in Specht rested on 14th Amendment due process grounds

rather than on the Sixth Amendment, showing that it was un

necessary to characterize the proceedings as "criminal"

in order to require that it conform to procedural due

process requirements.

4. Deference To State Penal Administration

Federal courts have traditionally deferred to the

presumed expertise of state prison officials, but matters

of penal administration are no longer accorded automatic

immunity from judicial scrutiny. It is now clear that

a state's right to regulate its own penal system does

not justify its interference with prisoners' federally

protected rights. See Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483

(1969); Wright v. McManh, 387 F.2d 519, 526-27 (2d Cir.

1967).

19

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 25919 )

)

)WILLIAM L. ELLHAMER, )

)Petitioner - Appellee, )

)vs. )

)LAWRENCE E. WILSON, Warden, )

)Respondent - Appellant. )

)

_____________________________________ )

No. 25953

CHARLES HINNINGTON,

Petitioner - Appellee,

vs.

DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, et al.,

Respondents - Appellants.

ERRATA

PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING CORRECTION IN THE BRIEF FOR THE AMICI CURIAE IN THIS CASE:

At page 20, line 7, the citation to Nolan v. Scafati,

430 F .2d 548 (1st Cir. 1970) should be followed by Shone v.

State of Maine, 406 F .2d 844 (1st Cir.) vacated as moot, 396

U.S. 6 (1969).

1095 MARKET STREET, SUITE 418, SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94103

It is no longer possible to rebut challenges

to state penal procedures by claiming that all constitu

tional rights were lost by virtue of the prisoner's

criminal conviction. State prisoners retain the right

to observance of procedural due process when additional

restraints are to be imposed on their already restrict

ed liberty. See Nolan v. Scafati, 430 F.2d 548 (1st.

Cir. ) vacated as moot 396 U-. S. 6 (1969); Car others v.

Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D.N.Y. 1970): Sostre v.

Rockefeller, 312 F.Supp. 863 (S.D.N.Y. 1970); Morris v.

Travisono, 310 F.Supp. 857 (D.R.I. 1970). See Baxstrom v .

Herold, 383 U.S. 107 (1966); Schuster v. Harold, 410

1 F. 2d 1071 (2d Cir.), c.ert. denied, 396 U.S. 847 (1969).

The parolee may not be a "free man", but he

enjoys far greater liberty then he would have if parole

were revoked. Certainly his status gives the parolee

at least as much right as the unreleased prisoner to the

protection of constitutional guarantees against oppressive

official, action. See In re Jones, 57 Cal. 2d 860, 862,

22 Cal. Rptr. 478, 372 P.2d 310 (1962).

Thus, none of the arguments offered by the state

20

to show that the parolee lacks a protectible interest

ih. his status ii convincing or even tenable under

recent cases. California procedures, are entirely in

adequate to protect that interest against arbitrary

or discriminatory government action.

Inadequacy Of Present Procedures •

The state has attempted to justify the summary

nature of suspension proceedings by pointing out that

a primitive kind of hearing is afforded later at the

time of formal revocation. (App. Br. 19-20).' Some

what inconsistently with its earlier description of

the revocation decision as discretionary, the state

concedes that at this hearing the Adult Authority

makes a "factual, determination on the parole violation

charges and determines whether they warrant a return

to prison or a refixing of the term previously set."

While accurately characterizing the nature and import

of the revocation hearing, the state fails to recognize

that this characterization necessarily implies that

the parolee is entitled to essential protections re

quired by procedural due process. The "formal revoca

tion hearing" does not meet these requirements because

it denies the parolee the right to counsel, to present

witnesses, to cross-examination, and to written finding

Aside from the procecural inadequacies of the

revocation hearing now afforded returned parolees, it

fĉ ils to meet the due process requirement that a '

constitutionally adequate hearing take place before

an individual is deprived of his liberty. In re Narcotic

M^j^lgn^ontro^Gommission v. James. 22 N.Y. 2d 545}

?-93 N.Y..S. 2d 531, 240 N.E. 2d 29 (1968). Cf. Goldberg

— U 'Se 25/4 (1970) ; Sniadach gv._ Family

F^anc e__Corg395 U. S. 337 (1969).

The parolee is deprived of his liberty at the

suspension stage, when the decision is made to return

him to prison for revocation proceedings. He may wait

60 days m prison before the revocation hearing, and

e\cn if the decision is then made to reinstate him on

parole, an additional delay may occur pending arrange

ment of a new parole program. (California Criminal

Law Practice §123.,58 p.606). Suspension means loss of

hard-to-find employment as well as separation from

family and deprivation of liberty in prison. It means

ihat, even if reinstated, the parolee will again have

to endure the difficult reentry period during which

most parole failures occur.

Revocation hearings are held in Vacaville and

San Quentin, which may be several hundred miles from

the residence of the parolee and his potential witness

es, and so as a practical matter the right to present

witnesses at that time would be a hollow one. Because

22

due process requires that a parolee receive a mean

ingful hearing, that hearing must take place in the

local community prior to suspension of parole.

The State1s Interest in Summary Adjudication

The nature of the governmental function in

volved in parole suspension proceedings, and the

parolee's interest affected thereby mandate observance

of procedural due process, unless the state has an

overwhelming interest $hich can only be served by summary

adjudication. See Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254

(1970). But the State of California has no strong

interests which are advanced by adherence to present

9 /procedure.— To the contrary, the state, like the

parolee, has an interest in insuring that there is an

accurate factual foundation for parole suspension or

revocation. The cost of keeping a man on parole is far

less than the cost of maintaining him in prison. — -

9/The state has not claimed that imposition of procedural

safeguards would unreasonably burden the administration

of the parole laws. In any event, it is now clear that

in the absence of more compelling affirmative reasons,

mere administrative efficiency will not justify the

omission of procedural safeguards which would otherwise

be required. E.g. Shapiro.v . Thompson, 394 U.S. 618

(1969) .-

10/In 1*966-67 the cost of maintaining one adult prisoner

in California was $2,623, while the average parole cos

was $572. per parolee. California Assembly- Committee

on Criminal Procedure. Deterrent Effects of Criminal

Sanctions, 38 (1968).

~ 23

In addition to the -direct saving to the state when a

man is on parole, there is no indirect -saving in welfare

costs, because many families are forced onto the welfare

rolls when the family wage-earner is sent to prison.”

Thus the state has an economic interest in keeping

parolees out of prison unless there is a firm factual

foundation for revocation.

In addition to its economic interest, the

state has an interest in advancing the rehabilitation

of criminal offenders. Parole systems have been.pro

vided precisely because they are regarded as sound

] 2/penological devices for fostering rehabilitation.—

No rehabilitative goal is served by revoking the

parole of a man who has not in fact engaged in serious

misconduct. Indeed, mistaken revocation, or revocation

based on an erroneous conception of the facts maybe

seen as anti-rehabilitative because it tends to under

mine the parolee's faith in the rule of law; and by

giving him a justified feeling of having been wronged

by society, discourages him from reflecting upon his

own responsibility to society.

No doubt a parole revocation proceeding in which

11/ Id. p, 39

12/See, e.g. Bates, Probation and Parole as Elements in

Crime Prevention, 1 Law & Contemp. Prob. 484 (1934)

24

a man t./as represented by counsel and accorded other

basic due process safeguards would take longer than

the present method. However, such a change would not

necessarily be regrettable. When a decision is to be

made of the seriousness of the one to deprive a man of

his freedom, it should be the-result of a solemn and

formal proceeding of sufficient duration to permit

measured deliberation and consideration of the issues.

The benefit to.be derived from a measured proceeding

were described as follows by the Court in Fleming v.

Tate, 156 F.2d 848, 850 (D.C. Cir. 1946):

"The parole system is an enlightened effort

on the part of society to rehabilitate con

victed criminals. Certainly no circumstances

could further that purpose to a greater extent

than a firm belief on the part of such offend

ers in the impartial, unhurried, objective

and thorough processes of the machinery of the

law. And hardly any circumstances could with

greater effect impede progress toward the desired end

than a belief on their part that the machinery

of the law is arbitrary, technical,too busy,

or impervious to facts."

25 -

CONCLUSION

■The judgment of the district court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

ALICE DANIEL

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

1095 Market. Street, Rm. 418

San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

December, 1970

26

APPENDIX A

CALIFORNIA ADULT AUTHORITY1S

COOPERATION WITH LAW ENFORCEMENT

NEW OFFENSES W

STATEMENT OF POLICY CONCERNING

REGARDING REVOCATION OF PAROLE

ITHOiJT PROSE CUT ION

FOR

Whenever a parolee comes to the attention of law enforcement for

a new offense, the parole agents, under established policy, are in

structed to cooperate fully with investigating and prosecuting

agencies. However, such cooperation is never intended as inter

ference, nor is it ever an attempt to influence the decision to

prosecute or forego prosecution.

Experience reveals that prosecution usually follows where evidence

is sufficient to establish guilt. However, there are a number of

exceptions involving cases in which prosecution agencies have in

dicated that the time, trouble and expense of prosecution seemed

unnecessary since the return to prison under revocation of parole

offered adequate protection to society.

In principle/ the Adult Authority is in accord with this approach.

In the past this procedure has been followed in some areas with such

good effect that it seems desirable that this policy be made clear

throughout the State so that the program may be adopted and followed

to whatever extent local agencies care to employ it.

The functions of the Adult Authority, of necessity, impose some litni

tations upon its participation in the application of this policy.

Therefore, in order to be fair and just and at the same time not

usurp the functions of other agencies, the following factors should

be present in cases submitted for this procedure:

1. The parolee must accept full responsibility for the

act or acts constituting the new offense and admit the

same to the parole agent; or

2. His guilt is so patent by the evidence amassed against

him that his admission of. guilt is of no materiality; and

Policy Statement #6

11/1/57

3. The maximum of the term presently being served by the

parolee must be sufficient to give adequate jurisdiction

commensurate with the gravity of the new violation; and

‘4. The request or initiation of parole revocation without

prosecution must come from the prosecuting agency of the

district.

In pursuance of this policy any District Attorney wishing to employ

this process of parole revocation may communicate such desire to the

supervisor of the nearest parole office. The supervisor will be

responsible, through established procedure, to immediately bring

the matter to the attention of the Adult Authority.

The decision of the Adult Authority will be transmitted promptly

to the District Attorney through the Chief of the Division of Adult

Paroles.

The foreging statement is not intended to limit or change in any

measure or degree the standards for parole performance, or the

policies relating to supervision, suspension and revocation of

parole. Such policies heretofore established shall remain in full

force and effect.

Policy Statement #6

11/1/57