Legal Research on Session Laws - 1981, Chapter 3

Unannotated Secondary Research

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Legal Research on Session Laws - 1981, Chapter 3, 1981. 4ce9fab2-d392-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/427834ad-96c9-497a-8d2a-e0b28400f726/legal-research-on-session-laws-1981-chapter-3. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Vlashington; and

:rd Skinnersville.

Gates, Hertford,

-Dnlbe CountY: 3

;hips ol' Halifax

rtland Neck; the

Hamilton and

s of Washington

ven and Pamlico

rbe and Halifax

Hawtree, River,

ty; the lbllowing

netoe), 5 ([.ower

Sparta), 9 (Otter

rky Mount), I3

;hip; of Halrlax

!letln, Roanoke

' (bunties."

the Chocowinity

Martin County:

, Williams, and

)r.runty; and the

nings, Nashville,

r Whitakers and

)ounty; and the

,lashville, North

akerc and Stony

Vance Counties;

y Wclls, Ferrells,

Creek, l*esville,

,ng townships in

!1, Creek, Shocco,

. Varrce Couuties;

y Wells. l'errells,

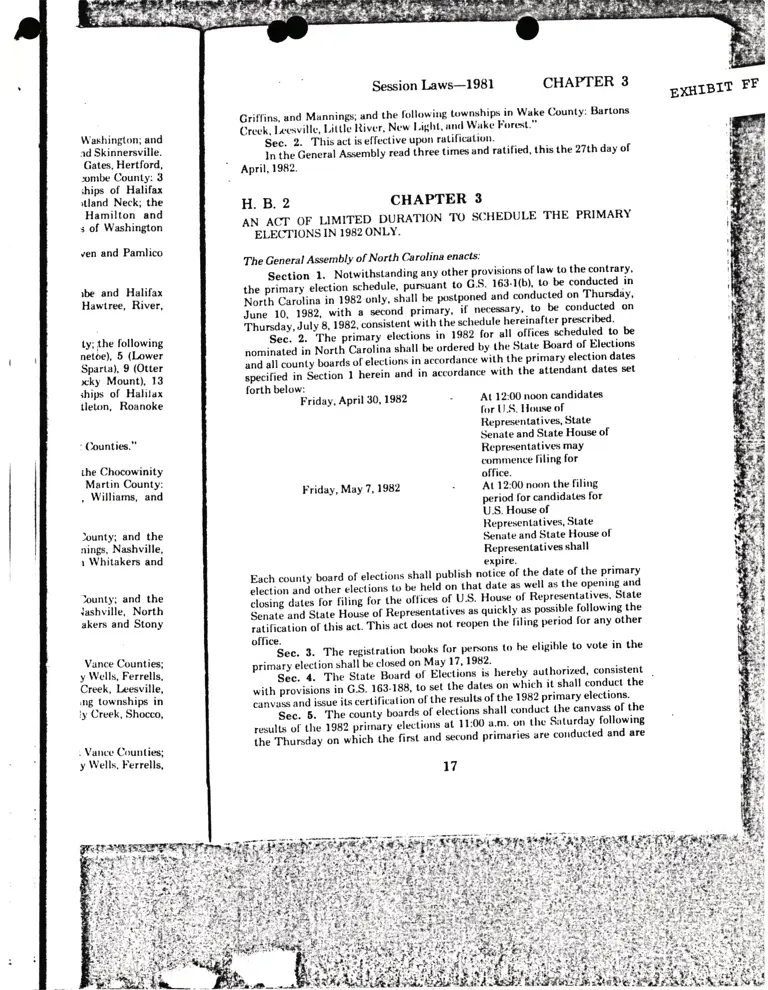

H.B.2

lorth below:

FridaY, APril 30' 1982

i'riday, MaY 7, 1982

At l2:00 ntrcn candidates

l'or I l.S. t lrxrne rlf

Representatives' State

lienate and State House of

RePresentativ€'ri msY

c(,mrrletlce I'il ing for

office.

- At t2:00 nrxrn the filirrg

period for candidates for

U.S. House of

cril.t.ins,andMannings;andthelilllrlwilrgtownshipsinWakeC<runty:Bartorrs

6r.-1,i.'*"lit.', l,ittt."" itivcr, Nt'* l'ight' rrrrrl Wlke l'ort*it.''

"'--

d"". 2- Titis act is el'fective ulrcrr ratiliutiorr'

ln the Generar n**.urv i"ad three times and ratil'ied, this the 27th day of

April, 1982.

Session [,aws-1981 CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 3

AN AgT OF LIMITED DURATIoN TO S(IHEDULE THE PRIMARY

ELEC'TIONS IN 1982 ONLY.

The General Assembly of Noilh Carolina enacts:

Sectionl.Notwithstandinganyotherprovisionsoflawtothecontrary,

the primary election *;;;];, ;fi;ant to d's' 163'l(b)' to be conducted in

NorthCarolinainlgS2rlnly,sh'llbegrstponalandconductedonThursday'

June 10, lgg2, with "-#;;

p.i-ar-y, il'necessary, to-be corrducted on

Thursday, July g, lgg2, "o*irt"nt'*ith

tf,e sclredule hereinafter prescribed.

Sec. 2. ff," pritn"'tv-"it"ii"n" in 1982 for atl ofl'ices scheduled to be

nominated in North cr;;ii.; ";;ii t urd"rod bv the srate Board of Elections

and all county boards ui"t".tlrn* in accOrdance *nitt tt," primary election dates

;fffJil 6";tim r r,"r"i" ancl in accordance with the attendant dates set

Rt'Presentat ives' State

il*"#f";l'J#:ii*'',

Each cou.ty board of erecl.iors.shall.publish .iii"tit the-date of the p.rimary

electiotr and other "f".tio]"

tu U" heli on that date as.well as the opetrirrg attd

;ffi;;i;-roi-iiline i;;l;; uiri."" ur U.s. House ol'Representatives, state

Senate and state no*" oj.iltpi"""ntrtires as quickty as possibre frllowing the

ratilication ol'this act. This act 6ots n.t re.,en the iiling period for any other

oll'ice.

Sec. 3. The regist'ration lxxtks for pervxts trt be eligible to vote in the

prima-rt'etection shali bc ckned on May l7' 198.2'

-

Sec. 4. TIre St";'d:;;;,| .rt: Ul".tiun-. is lrereby authorized, consistent

with provision. in C.S.iO{-il8',;r r"t tt" dates on wirich it shall conduct the

canvass and issue ir^. ""*iii".rr

iul1

"f

in" results of the 1982 primary elections.

Sec. 6. fn" .orniy'Lo*rraL "i"f".tions

shall conduct the canvass ol'the

results ol the 1982 t,'i';;t;;;iiui'* ut ll:(X) u'nr' ott tltc Slturday following

the Thursday on *r,i.t'ii'.

-ri*i

,"a s'et.'nd primaries are colrducted and are

li*

'.1 :

r7

OHAI'I'ER 3 Session [,aws-I981

*;,'

-1?:,

,':t.

u-,i

hereby authorized tg utilize the necessary cuunty government l'acilities and

acconirnodatiorrs itt or<ler to complete said resp<lnsibilities'

Sec. 6. 'I'he State Board of Elections shall prepare arrd distribute to the

courrl5' boarrls ol elct:tiotts a lievised Prilnarl'Election Timetable 1982, setting

,ut ih. a,pliculllc lilirrg peri,d l'or ca,didates for U.S. House of

Hepre*eulaiives, State Senate and Stale House of Representatives along with

all'otlrer lrcrtirrerrl rlutes rclltive to the prinrury elc.ction timetable as required

by provisiorrs sprcilied irr this act. Each cuunty board of elections shall make a

copy ol the timetable available to the news media.

sec. ?. 'I'he state Board ()l' Elections shall implement the provisions of

t6is act arrtl shall lx,;ruthoriz.ett to ussigrr rtxporrsibilititx attetrdant thereto

pursuunt to provisiotrs trrtttairtetl in C.S. l6:l-26 and G-S. 163'27.

Sec. 8. Applir.aiiolrs lbr allsentee ballols shall be received consistent

with the scheduie s*cit'ied in C.S. 163-t09(b), G.S. t63-227.2(b) and G.S.

l6il 227.and ubsenteeballots lbr all olfices except North Carolina State Senate

arrd North (,'arolirra State H0use of Represt,ntative,s shall be issued promptly

cotrsistettt with strtutory rtqttirettretrts. The State Board of Elections shall

ilstruct all r:ourrty lxrards ol elections to the end that all requirements

corrlained in this act are a<lhered to.

Sec. g. Absentee ballots are authorized lbr the olTice of U.S. House of

Represetrtatives arrd shall be issued as quickly as the ballots can be made

,..rilul,t".'Ihe requirctrrcttt tlrat alx;etrtec ltalltrts shall be available lbr voting at

least tio days prioi to tlre date ol'the prinrary shall not apply with regard to the

l9tt2 prinrary electiotts orrly.'l'tre Stule Board of Elections shall instruct the

counti, b,rards ol' elections ott the prtx'erlure to follow to ensure expeditious

supplt:nrerrtal issuattce by rtrail to csch voter wlttl previously'was-issuedabsentee

haiirrts, as pronrptly as possibte al'ter the trallots for U.S. House of

Itt,preserrtativcs urt, avuililblc it llrost'llirlkrts are tlot yet availallle when the

v,ier applies. N, adrliti.nal applir:ation shall be required liom any voter whose

llpplicaiit,n was appror,(.rl arrrt t(} whorn all other ballots svailable were

;lrt'v iousl.y nru i letl or ttl ltt'rw ise isstted'

Sec. 10. Absentec bulkrts shatl be atrttrorized firr the ol'l'ices ol'North

('arelilra Stlrle St,rrirle urrrl Nortlr ()arotirra Hottse ol'Rt'pre*;errlatives lbr the

lgll2 prinrary, arut tirr the l'irst prinrary shull be issued supplementally to all

p,,r*,,u* u,trri wert, llreviously issucd hallols as soon as thc bulkrls lbr those

ol'l icts are preparerl.

Sec. ll. No pt,rsorr sh:rll l,c;rcrnritted to l'ile as a candidate in the

;lrirrrur.l, lirr tJ.S. tlotr*r, ol llt'llrcsettlirlivt's, North (}rrolitra State Setrate or

i\orth (lar.rlirrir lkrusc ol licprcserrtltivcs who has charrged his political party

al'l'ililtien or whe h1s clrirrrgerl l'ronr unal'l'iliatetl status to party al'l'iliation as

pernliltcd irr G.S. l(i3,74(b) unless such persorr shalt have al'l'iliated with the

lxrliticul parl.y irr wlticlt lre seeks to be a cutrrlirlale lbr at least lhree months

pri.rr to il,e l'ili,,g dcatlline s;11,r.il'ier.l in G.S. I63 106(c) as $'as applicable to all

t.rrrrtlirtates lirr Sl.rle :rrrrl disirict jutlicial ol'l'ice*; and all courriy ollices which

l'iling period expire'rt at l2:00 rlo()n olr l'ebruary l. 1982'

Sec. 12. Wlrcrrever irr accorduttce with the provisions o[ any local or

ggrre rrrl lau, :r llritrrlr.v or t.lrtliorr lirr l lxrrrrt ol't'ttttlittirltl or rttltcr ol'licc is trl be

ii"l,t ,,r, ttre rlitc ql'Ilte prirrtary clt'ctiolr, or it is sct to bc orr the'l'ucsday al'ter

lhe l'irst Mrtrrda.y irr M,r.v irr lgtt2, it slurll he lrelrt on the d:rle provided in

Section I

ehall be h

Sec,

Represer

Reprerit'tr

primary,

Board o[

(t)l

(2) (

has the s

(3) I

the prim

that dist

accompli

ol'fices or

(4) l

ballol^s ir

Ina

the mell

precinct

shall be

days prit

Set

several 1

electiont

precirrct

or it ma

this sect

Ser

to fill vr

election,

lienate,

county I

precinct

executi\

standirrl

nonrinal

vote. Rr

the Stal

Se

applied

the ol'fi

Carolin

Se

in 1982

order o

apporti

prinrarl

shall rx

Cenera

l8

CHAPTER 3 Session Laws-1981

l'. r4

-.,_! t

.t

?l

*,. i

&i,

hereby uuthorizetl to utiliz.e the ttecesury county government fucilities and

acconimodatiorrs in order to complete said responsibilities.

sec. 6. The state Board of Elections shall prepare and distribute to the

cuunty lxrards ol'elccl.iotrs u ltevised Primary Election Timetable 1982, setting

out ihe applicable l'iling period for candidates for U.S. House of

Repre*errlaiires, Sl"alt. Scrrate urrrl Stute House of Representativm along with

all o1her peitinent dates relative to the primary election timetable as required

by provisions specilied in this act. Each county board of elections shall make a

copy ot the tinretable available to the news media'

sec. ?. 't.he state lhrurtl ol' Elections shall implemeni the provisions of

this act and shall be authorized to assign responsibilities attendant thereto

pursuant to provisiotts corrtairred in G.S. 163-26 and G.S- 163'27.

Sec. 8. Apptications lbr atrsentee ballots shall be received consistent

u,ith the scheduie specil'ied irr C.S. 163 109(b), G.S. 163-227.2(b) and G'S'

l6:t.22?, arrd absentee llallols lbr all ol'lices except North carolina State senate

a1<l Ngrth Carolina State Hou^se of Representatives shall be issued promptly

clrrsisteut wit[ stlttrtory rtquirt'ltlctrls. 'l'hc Stute Bourd ol' Elections shull

instruct all county boards ol' elections to the end that all requirements

corrllined in this uct are urllrcred to.

Sec. L Abcentee ballots are authorized for the oflice of U.S. House of

Ilcpresenllllives arrrl shall l)e issued us quickly as the ball<rts catt be made

ur,rilul,l". Tlre requirenrerrt tlrat altsentee balkrts shall be available lor voting at

least 60 days prioi to the date ol the prinrary shall not apply with regard to the

l9tl2 primary elections orrly.'I'he State Board of Elections shall instruct the

county btards ol'eler:tions on t.he prtrcedure to follow to ensure expeditious

supplemelrtal issuattce by nrail [o each voler who previously was-i<s^t'ed absentee

baliots, as pronrptll'as possible atter the ballots for U'S' House of

Rellreserrtatives ari,rivaililhle il'thost'b:rtlots are not yel. available when the

vgter applies. No ltlrlitiorral upplit:atiorr sltatl Ire required frum arry votet wlrtxe

applicaiiOn was approved and to whom all other ballots available were

previously mailed or tltherwise isstred.

Sec. 10. Abserrtee ballots shall be authorized for the ofl'ices of North

Oarotina State Senale and North Carolirra House ol'Representatives lbr the

l9tl2 prirnary, arrrt lirr ttre t'irst prirnury shall be issued supplenrentally to all

p".*rn, whJ wt,re previously issued ballots as soon as the ballots for those

ol'l'ices are prepared.

sec. 11. No person shalt bc permitted to file as a candidate in the

prinrary lbr u.s. llouse ol' Representatives, North carolina state senate or

i\orth i)arolirra House ol Reglresentatives who has changed his political party

al't'iliation or u,ho has changed t'rom unal'l'iliated status to party al'l'iliation as

pernritted in G.S. l(i3 ?4(b) urrless sut'h person shall have al'liliated with the

p6litir.al party in which he seeks to lle a candidate lbr at least three months

irrior t6 tn" fiti,,g tleatltirrc specil'ierl in G.S. 163-106(c) as was applica[le to all

carrdi{ates lbr State artd clisirict judicial oltices and all county ofl'ices which

l'ilirrg pt'rirxl cxpirut at l2:(X) ll(xrn ott l'elrrtnry l, 1982'

Sec. 12. Whenever in accordance $ith the provisions ol'any local or

g,t,leral law a llrilrrirr.y or elctlion l'rlr a lxrarrl ol'educution or ttllter ol'l'ice is to be

ircld un the date ol' ilrt, grrirrrury ele,ction, or it is set to be on tlre Tuesday aller

the l'irst Monday in May in l9ll2, it shall be held on the date provided in

tiectiorr

shall be

Se

Represr

Represe

primarr

Board o

(t)

(21

has the

(3)

the prir

that dir

acconrp

ol'lices r

{4

ballols

Irr

the me

precinc

shall tr

days pr

Sr

several

electio

precin<

oritn

this ser

s

to fill

electio

Senatc

countl

precin

execut

standi

nornin

vote. l

the St

s

applie

the of

Caroli

f

in 19{

order

appor

prinra

shall

Genet

,4.-

g

i-l1inl"i,r lt;

d iaa;

a ir.: 'tt

tr*. *:;

l8

It.-

Session Laws-l981 CHAMER 3

nd

Itc

ng

ol'

th

ed

'll

section I ol'this act, and any election or runol'l scheduled lbr lbur weeks later

"f,"if

U" held on the date.p"iili"d in Si'ction I [or the sec.nd primary.

Sec. ll. Whe,crt.i irr arry a,;xrrlirttttt.ttt ,larr lirr tlrc ll.S._ll.usc .f

n"pr".*trtives, North Caroiina lienate or North Carolina House ol

ii"ii*..triires, a precirrct is placcd itt tw, ,r nrrtre distrir:t-s, arrd there is a

;;fi;;y, it"n tt" lountv uoaia or electio.s,.with the approval ol'the St-ate

boata of Et""tions may' lor the 1982 primary election:

(l ) Divide the precinct into two or more precincts'

(2) change precinct lines to place part ol'the precinct with a precinct which

has the same election district.

(3) Keep the same precinr:t but asuertailr eitlrer irr atlvuttt'e rlr ott tlre date ol'

the prinlory'*hich distiict the voter resides itt, antl iIa prinr:rrv is lrt'ing held in

tnat aistrict. give the voter ttre ballots lbr tlre ilpllropriate.<listrict''l'lri's nray lr

utrrlrnplisherilry , 1rr1u,, It,lLrt lirr ll*'rll'l'it:e ev.t il :t lttitt'hitt. is ttstll lor olltt'r

oll'ices or other voters.

(4)Prrlvirtesonreoltrerprtrce<luretrreltsurethateachvttlt,rd<xrrntllcast

ballots in more than otte district.

In adopting u pru.e(lure ultder tltis sectiott, tlre Lloard shall attt'nrpt to use

the methoi wh;ch'is least disruptive to the voter, and any acti.n to change

;;;.ii;"a liDe+ strall rr. trr,i,,, in ar:corrlancc with c.s. t63 28 except thal notice

If,rif U. given not less than l5 days prior to the prinrary election instead of 20

days prior to the close ol rcgistration

Sec.14.Incasethe"areainanymilitaryreservationlraslreenplacedin

"or*roL

pr""irrcts witlr0ut rlclilrite lirlels huvilrg lxmtt tlrawtt, lltc urultty txt:rrrl o[

"i"Ji"rr'.

ma1, provide for the entire military reservation to be in one election

;;;;;;;;1, irripective o[ towrrship lines !1 sccor<tarce wi15 sccriorr l3

'1

tlris act.

;; it *;i use an altenrrtir",tuiud in lbr:tion l3 ol'this 8ct. Any action under

tlris stction must be approved by the state Board ol'Elections.

Sec. 16. lrr tlrc case ol uili*trict exccutive cotttntittcc urrrlcr C.S. 163'l l4

to l'ill vacancies anrong party nomittees occurrillg alter tltttltirtatioll artd belbre

i,iu,'ri,rrr, in cases *truiL'1,,,ri,l the crlurtly is-irr a ll.S. tlottstt. Norlh ("arolinu

S"nrt", or Nofth Caroliria ll,use district witlr all or part ol'artother county. a

".r,r,ttS"

politicat party. in choosing nrcmbers, .shall allow ontl delegates from

urecinct" within the diriri.t to ,Lt" in electing the nrembers o1 the district

;;ili;;; ..rr"iitt"". In a case where a district cottstitutes part ol 8 county

;;;irg atone, and trrl .,,r,rty executive comnrittee is to v.te t, l'ill the

nunrinriion,,rniy nrenrlreni ol th-e conrnrittee who reside within thc district may

vclte.Ruleslbrvotingshallhepre*-ribedbytheStatepartychairnrattullle,ss

the State purty provides rttltcrwise.

See. 16. For the 1982 primary election orrly' C'S' 163-l12.shall be

,ppli"JLy substituti,g "f 0 rtjfs" lbr':30 days" whercver it a,pears, itrsofar as

the.l'l'ices ot'U.S. Uu.]*"-uf nlpresentati'esl North Car,lina lienate, or Nort5

(larol irra House are ctlttcertted.

sec. 1?. Inttreeverrt(|l'anydelayintlrecottrtuctol'ttrepritnaryelection

in 1982 lbr the ollices ul:Stot" Se,,atc or St.utc llttusc ol ltepreserrtalives by

,,"f.r,rf uny corrrt ,rf',rrn,g^,i"ut jurisclitliort or lxrcituse citller or txrlh plutrs rlf

upfurtiu,rn*,rt have n,,t il"",' ap'proued-urrder the Volirrg Riglrts Act' tlren tlre

illrrrv lirr Nortlr Oairliuu Iluu"" or N.rth ()ar.lirta Scrlate. as a,pr.,riate.

shalt not be held ,n.ru,," ro' l9tl2, but shrrll lrc held rrrr a date trrtlered by tlre

Ge.eral Assenrbly ,,, 1rj

"

court ()l' c,nr,ct.rrt jurisdicl.i.n. A delay in tlre

nt

.s.

te

l.v

.rll

tLs

ol'

de

at

hr'

.le

ils

ee

ol'

'lt

h

le

.ll

ol

to

t(,

,r

r)'

IS

t}l;'.!{r"l

I Br-,til

XrE1i.':"1:

ri;i;';i

$$H

le

ls

lt

h

rr

.T

D

r9

CHAP'TER 3 Session Laws-I981

primary lbr one house does not automatically delay the primary for the other

house.

Sec. 18. Tlrr provisiorrs ol'this act shall be tenrlrcrury and shall apply

only to the 1982 prinrary elections conducted in North Carolina and its

provisiorrs slrall ex;rire on tieptember l, 1982; however, its provisions shall

temporarily susJrend all requirenrents in law to the contrary until the date of

expiration.

Sec. 19. A cop.y of this act shall be mailed to each county board of

elections by the l*gislative Services Ol'l'ice imrnediately upon ratification.

Sec. 19.1. G.S. 163.22.2 is amended by rewriting the first two lines to

read:

"ln tlre event any portion o[ Chapter 163 of the General Statutes or any State

election law or form ol'election of any county board of commissioners is held

unconstitutional or invalid by a State or Federal Court or is unenforceable

because ol objection interposed by the United States Justice Department under

the Voting Rights Act and such ruling".

Sec. 19.2. In the case of any local election to be held under G.S. 163-287

or G.S. 159-(il on.lunc I0, I9tl2, l'irst notice shall be published at least seven

days belbre re1;istration b<xrks are to close, rather than 20 days or 14 days,

respectively.'l'he rtrgistration lxxrks for all elections to be held on June 10, 1982,

shall close on May 17, 1982.

Sec. 19.3. Notwit"hstarxlirrg anything in Article 20 ol'Chapter l68 of the

Gencral Slatutes, the deadlitre lbr issuance of absentee ballot applications and

for orre.stop ubsentee voting shall be Monday, June 7, 1982, for the first

primary, and Tuc,sday, July 6, 1982, for the second primary.

Sec. 20. Scctiorr 3 ol'Ohupter I130, Scssion laws of lg8t, and Chapter 3

ol' Ext ra Session laws ol' I9tt2, First Extra Session, in ils entirety, are repealed.

Sec. 21. 'Ihis act is el'l'ective upon ratification.

In the General Assembly read three tinres and ratified, this the 27th day of

April, l9tl2.

H

A

&

t9

He

an

r9

int

l8

At

H

A

8p

Be

8p

nri

an

Li,

acl

th,

&

th

Al

l.

t.

h

t,

I

I

I

I

i

(

I

I

!

t

I

t

:

tH

l6

I

B,

th

E:

ut

.{

.4

)ffi !8!fliilffF.ffi riffi lRIlStSdE rer*$.

A1