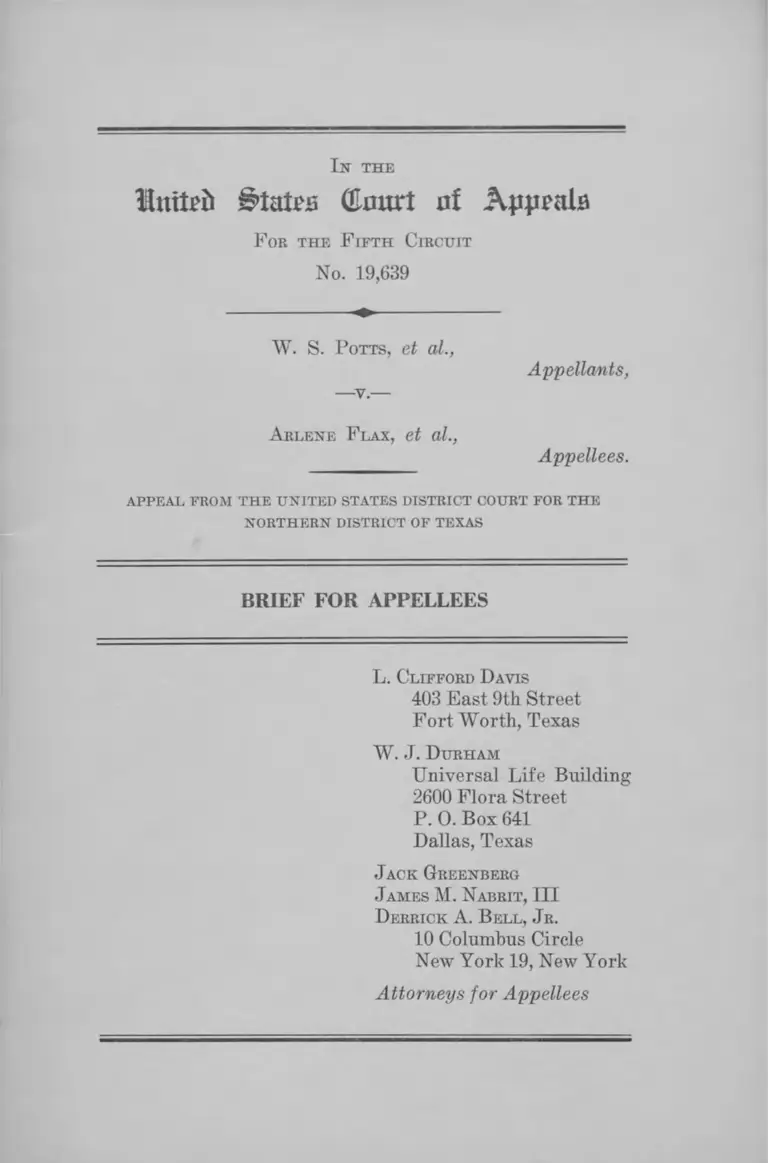

Potts v. Flax Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Potts v. Flax Brief for Appellees, 1962. f6b0cb6e-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/45d73813-5893-437e-aadb-4651d1e10319/potts-v-flax-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

United ^tata (Eourt of Apjipala

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 19,639

W . S. P otts, et al.,

—v.

A rlene F lax, et al.,

Appellants,

Appellees.

appeal from the united states district court for the

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

L. Clifford Davis

403 East 9th Street

Fort Worth, Texas

W. J. D urham

Universal Life Building

2600 Flora Street

P. 0. Box 641

Dallas, Texas

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A . B ell, J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellees

I N D E X

Statement of the Case..................................................... 1

A rgument :

I. Appellees were not required to exhaust the

administrative remedy provided by either

Texas Law or School Board Regulations

prior to invoking the jurisdiction of the

court below..................................................... 7

II. The Court granted appropriate relief for

plaintiffs and others similarly situated in

ordering the defendants to submit a plan

of desegregation for the Fort Worth school

system ............................................................. 14

III. The District Court properly declined to con

vene a three-judge Court under 28 United

States Code Section 2281 .............................. 17

IV. Neither the plaintiffs’ motives in bringing

the suit or the fact that others are aiding

plaintiffs in the expenses of litigation are

relevant ......................................................... 21

Conclusion ..................................................................... 23

A ppendix :

Article 2901a ........................................................... la

Article 2900a........................................................... 6a

PAGE

11

Table of Cases

PAGE

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark.

1959), aff’d sub nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U. S.

197 ................................................................................ 20

Atkins v. School Board of City of Newport News,

148 F. Supp. 430 (E. D. Va. 1957), aff’d 247 F. 2d

325 (4th Cir. 1957) ..................................................... 18

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31, 7 L. ed. 2d 512

(1962) ......................................................................... 20

Beale v. Holcomb, 193 F. 2d 384 (5th Cir. 1951) ....... 17

Borders v. Rippy, 247 F. 2d 268 (5th Cir. 1957) ....... 16, 20

Boson v. Rippy, 275 F. 2d 850 (5th Cir. 1960) ........... 15

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ............. 10,19

Braxton v. Board of Public Instruction of Duval

County, Fla., unreported order of March 1, 1961

(S. D. Fla., No. 4598-Civ-J), mandamus and prohi

bition denied, sub nom. Board of Public Instruc

tion of Duval County, Fla. v. Hon. Bryan Simpson,

366 U. S. 957, 6 L. ed. 2d 1267, 81 S. Ct. 1944 (1961) 21

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483

(1954) ........................................................... 5,7,9,12,14,22

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 .......7, 9,11, 22

Burnes v. Scott, 117 U. S. 582, 29 L. ed. 991, 6 S. Ct.

865 (1886)......................................... 22

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 138 F. Supp.

336, 138 F. Supp. 337 (E. D. La. 1956), aff’d 242

F. 2d 156 (5th Cir. 1957) .......................................... 18

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp.

42, 188 F. Supp. 916 (E. D. La. 1960), aff’d 365

U. S. 569......................................... 20

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 242 F. 2d 156

(5th Cir. 1957) 16

I l l

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956)....... 8,12

City of Newport News v. Atkins, 246 F. 2d 325 (4th

Cir. 1957) ................................. .................................. 13

Cleveland v. United States, 323 U. S. 329, 65 S. Ct.

280, 89 L. ed. 274 (1945) .......................................... 19

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ................. 7,11,12, 22

Dodson v. School Board of the City of Charlottes

ville, 289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961) .......................... 10

Doremus v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 429, 96

L. ed. 475, 72 S. Ct. 394 (1952).................................. 21

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ....... 12

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202, 3 L. ed. 2d 222, 79

S. Ct. 178 (1958) ........................................................ 22

Ex parte Bransford, 310 U. S. 354, 84 L. ed. 1249,

60 S. Ct. 947 (1940) ................................................... 18

Ex parte Collins, 277 U. S. 565, 48 S. Ct. 585, 72 L. ed.

990 (1938)......................... .......................................... 19

Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1961) ......... 9

Foremost Promotions v. Pabst Brewing Co., 15

F. R. D. 128, 19 F. R. Serv. 26b.31, Case No. 4

(N. D. 111. 1953) ......................................................... 22

German v. South Carolina State Port Authority,

295 F. 2d 491 (4th Cir. 1961) .................................. 18

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade

County, Florida, 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959) .....8, 9,10,

15, 20

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke,------

F. 2 d ------ (4th Cir., No. 8534, May 22, 1962) ....... 10,15

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp.

649 (E. D. Va. 1961), aff’d 368 U. S. 515, 7 L. ed. 2d

521 (1962) ..................................................................... 20

PAGE

IV

Hill V. School Board of City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473

(4th Cir. 1960) ........................................................... 10

Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp. v. Epstein, 30

U. S. L. Week 4599 (June 25, 1962) ........................ 19

Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp. v. Rohan, 289

F. 2d 426 (2nd Cir. 1961) .......................................... 19

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E. D. Va. 1959) 20

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, Va.,

278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ...................................... 9,15

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939) .......................... 12

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d

370 (5th Cir. 1960) ....................................8, 9,10,15, 20, 21

Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chatta

nooga, 295 F. 2d 617 (6th Cir. 1961) ....................... 14

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County,

------ F. 2d ------ (4th Cir., No. 8535, June 12,

1962) .........................................................................10,15,16

NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E. D. Va. 1958),

vacated on other grounds, sub nom. Harrison v.

NAACP, 360 U. S. 167, 3 L. ed. 2d 1152, 79 S. Ct.

1025 .............................................................................. 21

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of

Memphis, ------ F. 2d ------ (6th Cir., No. 14642,

March 23, 1962), cert, denied 30 U. S. Law Week

3398 (June 25, 1962) ..............................................10,15,16

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156

(5th Cir. 1957) ............................................................. 13,14

PAGE

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896) 11

y

R.R. Comm, of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 U. S. 496,

85 L. ed. 97, 61 S. Ct. 643 (1941) .............................. 12

School Board of the City of Newport News v. Atkins,

246 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1957) .................................... 17

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education,

358 U. S. 101 (1958), aff’g 162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D.

Ala. 1958) .....................................................................8, 9,17

Stark v. Brannan, 82 F. Supp. 614 (D. C. Cir. 1949),

aff’d 185 F. 2d 871 (D. C. Cir. 1950), aff’d 342

U. S. 451, 96 L. ed. 497, 72 S. Ct. 433 (1952) ........... 22

Stratton v. St. Louis, Southwestern R. Co., 282 U. S.

10, 75 L. ed. 135, 51 S. Ct. 8 (1930) .......................... 18,19

Stuart v. Wilson, 282 F. 2d 539 (5th Cir. 1960) ....... 18

Turner v. Memphis, ------ U. S. ------ , 7 L. ed. 762

(1962) .......................................................................... 20

Wheeler v. Denver, 229 U. S. 342, 57 L. ed. 1219,

33 S. Ct. 842 (1913) ...................................................

Wichita Falls Junior College District v. Battle, 204

F. 2d 632 (5th Cir. 1953) ..........................................

Young v. Higbee Co., 324 U. S. 204, 89 L. ed. 890,

PAGE

65 S. Ct. 594 (1945) ................................................... 22

Federal Statutes Involved

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23(a)(3) .... 15

United States Code, Title 28, Section 1331................... 1

United States Code, Title 28, Section 1343(3)............. 1

United States Code, Title 28, Section 2281 ...............17,19, 20

United States Code, Title 42, Section 1981................... 1

United States Code, Title 42, Section 1983 ................... 1

22

17

I n t h e

llttttrii States (Emtrt of Appeals

F or t h e F i f t h C i r c u i t

No. 19,639

W . S. P o t t s , et al.,

Appellants,

—v.—

A r l e n e F l a x , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement of the Case

An amended complaint was filed in this action on No

vember 30, 1959, in the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas by plaintiffs Weirless Flax, Sr.

and Herbert C. Teal on behalf of their minor children (R.

1). The defendants are W. S. Potts, President of the Board

of Trustees of the Fort Worth Independent School District,

the Trustees, the School District itself as a corporation, its

superintendent and the principals of the two schools where

plaintiffs’ children were denied admission. Jurisdiction was

invoked under 28 U. S. C. §1331 and §1343(3) and 42 U. S. C.

§1981 and §1983 (R. 2-3).

Based on allegations that the defendants operate the

Fort Worth public schools on a dual racial system, plain

tiffs seek relief for themselves and all other Negroes simi

larly situated against defendants’ policies which require

2

minor plaintiffs to attend racially segregated schools. The

defendants on November 19, 1959 filed a Motion to Dismiss

and their Answer (R. 16, 21) which, in summary, denied

that plaintiffs had been assigned on the basis of race, but

had been assigned to schools “designed to best serve their

educational needs” (R. 22). In a lengthy “ Additional An

swer” (R. 28), defendants maintain that their dual racial

system, followed for more than 78 years, “has become a

fundamental part of the educational process in Fort Worth”

(R. 29) and that a change to an integrated system “ could

only lead to confusion, chaos, and a complete breakdown

of the public school system . . . ” (R. 29). Moreover, defen

dants referred to state statutory provisions which in the

event of integration would severely penalize the school sys

tem and its personnel (R. 31). Finally, defendants maintain

that plaintiffs failed to pursue administrative procedures

provided for transfer to any other school, which proce

dures established by state statute provide adequate reme

dies for the recognition of plaintiffs’ rights (R. 33).

Prior to trial on April 3, 1962, defendants took the plain

tiffs’ depositions in February 1960 (R. 35), obtained a con

tinuance of the trial in May 1961 (R. 41), based on the ill

ness of the School Superintendent and filed on November

7, 1961, a motion to assemble a 3-judge court which was

refused by the district court (R. 53).

The testimony and exhibits introduced at the trial of this

case on November 8, 1961 (R. 69), entirely support the

finding of the court below that appellant School Board has

continued to operate a dual racial system of compulsory

public schools in the Fort Worth Independent School

District.

Succinctly, the public schools in the Fort Worth Inde

pendent School District for 78 years have been operated

under a dual system requiring Negro pupils to attend

schools operated exclusively for Negro pupils and white

3

children to attend schools operated for whites (R. 28-29,

108). This policy remains in effect, and the appellant Board

has no plans to change it (R. 109, 111, 232).

The dual racial system is a fundamental part of the edu

cational process in Fort Worth (R. 29) and, according to

school officials, both white and colored teachers are best

suited by experience, training and habit to the teaching of

children of their respective races (R. 226). Appellant mem

bers of the Board of Trustees and the executive personnel

of the School District’s administrative staff testified at the

trial of their conviction that the dual system, segregated

on the basis of racial color and operated under the doctrine

of separate but equal teaching and facilities, was the plan

best suited to the schools under their jurisdiction (R. 158,

181, 226). This conviction, which the court below found

appellants held in good faith (R. 60), was reinforced by a

study of the desegregation question made over a period of

seven years by the Superintendent and other members of

the administrative staff (R. 185).

The dual system in the Fort Worth schools is made up

of two classes of schools with reference to race. Negro

pupils are restricted to Negro schools and white pupils are

restricted to schools for whites (R, 107-108). Children are

assigned to schools in accordance with a dual set of zone

maps based on race (R. 121). The Fort Worth schools

serve about 59,062 white pupils and 13,836 Negro children,

Negroes comprising about 18.9% of the total (R. 202).

During the enrollment period at the beginning of the 1959

Fall Term, Weirless Flax, an Air Force Sergeant (R. 74)

and a Negro (R. 72), presented his 6 year old daughter,

Arlene, for admission to the Burton-Hill Elementary School

(R. 73), which school is restricted entirely to white pupils

(R. 221-222). The Principal of that school said he had in

structions from the school board not to enroll Negro chil

4

dren in the school, and refused to permit the Flax child

to enroll there (R. 74). She was required to enroll in the

Como Elementary School (R. 75), which school is restricted

entirely to Negro children (R. 100).

Appellee Flax lives in an apartment building on the

Carswell Air Force Base (R. 71) 1% miles from the Burton-

Hill School (R. 126) and about 5 miles from the Como

School (R. 127). White children living in the same apart

ment building on the Carswell Air Force Base as the Flax

child who were presented for enrollment at the Burton-

Hill School under similar conditions and during the same

period in which Arlene Flax was rejected, were accepted

(R. 81).

In similar fashion, appellee Herbert C. Teal, a Negro

resident of Texas (R. 87), presented his six children during

the enrollment period at the beginning of the 1959 Fall

Term for enrollment in the Peter Smith Elementary School

located only 7 blocks from his home (R. 87, 91), which

school is limited to white children (R. 99, 100). The Princi

pal of that school, acting under instructions of his superiors,

refused to admit the Teal children because they were Ne

groes (R. 90), and they were required to enroll in the all-

Negro George Washington Carver Elementary School (R.

99, 100), located in another geographical school area two

miles further from their home than the Peter Smith School

(R. 92). Previously, appellee Teal had attempted to regis

ter his children in the Peter Smith School at the beginning

of the terms in 1956 (R. 87) and 1957 (R. 89, 98), but was

refused on both occasions.

On these facts, appellees brought this suit without making

an effort either to follow the transfer procedure adopted by

the Board in 1948 (R. 129-131), or to use the administrative

remedies set forth in Article 2901a, Texas Civil Statutes,

the provisions of which law are set forth in the appendix

5

to appellees’ brief. Boai-d officials admit that unless the

Boai’d abandons the dual system policy, they will have no

authoi'ity to grant such transfer requests (B. 135, 136).

Both appellees testified that they sought and obtained aid

from the NAACP in bi’inging this suit (R. 78, 96), and not

withstanding some confusion on the part of one of the

parents (R. 101), the court below found that allegations in

the complaint were sufficient to properly designate the suit

as a class action (R. 58).

The appellant Potts, President of the Board of Educa

tion, stated as his belief that the dual system is “ for the

best interest of all the children” (R. 148), and thinks that

both the Board members and 95% of the people are in

accord with this view (R. 148, 167). To suppoi’t this posi

tion, the Board President quoted figures intended to show

the progress Negro pupils have made in the system since

1955 when they were 2.04 years behind the average white

child by the time they reached the sixth grade (R. 151).

By 1960, after the Board equalized Negro teachers’ salaries

and standards (R. 194, 200) and improved Negro school

facilities (R. 195-200), Negro children were 1.40 years be

hind the white children in the sixth grade (R. 201).

The Board President stated as his contention that the

Brown case does not mean that the dual system can no

longer be maintained in the schools (R. 154). He said that

the Board was defending this suit aimed at abolishing the

dual system because Texas law (Article 2900a, Texas Civil

Statutes) requires it and voluntary desegregation would

mean a loss of the state appropriation, would subject the

school officials to fines and imprisonment and would cost

the school system its accreditation (R. 145-146). He ad

mitted, however, that the Board has made no effort in the

state coui't to determine the validity of the Texas law (R.

6

160), and lias not sought an opinion from the State Attorney

General on its validity (R. 184).

Because the Board feels that segregated schools are best

for their system, in part, because “ Negro teachers are far

better able to teach Negro pupils and white teachers better

able to teach white pupils” (R. 158), the Board has taken

no action on any desegregation plan (R. 232).

At the conclusion of the trial, the court below entered

appropriate findings of fact (R. 58-64), and concluded that

the dual system for white and colored students in the Fort

Worth public schools violates the rights of the minor plain

tiffs and all eligible Negro pupils (R. 65). The court found,

moreover, that the biracial policy was so firmly fixed and

maintained with so much conviction that “ there is no rea

sonable probability within the foreseeable future of a vol

untary change” in the segregation policy (R. 61). For this

reason, the trial court concluded that it would have been

futile for the plaintiffs to exhaust the administrative pro

cedures under Article 2901a of the Texas Civil Statutes.

And since these procedures were not required of white

children similarly qualified, the trial court found that pro

cedures are in themselves a violation of the constitutional

rights of plaintiffs and the class they represent (R. 65).

The trial court also found that Article 2901a, when construed

in connection with Article 2900a, Texas Civil Statutes, if

not invalid on its face, does, as applied by the Fort Worth

School Board, violate the Federal Constitution (R. 65-66).

Finally, the court on December 14, 1961, ordered the

appellants to submit within 30 days after the judgment

became final “a plan for effectuating with all deliberate

speed a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school

system beginning with the 1962 Fall School Term”, and

retained jurisdiction during such period of transition to

insure compliance (R. 66).

7

Defendants filed a motion for new trial on December 22,

1961 (R. 254), in which objections were raised to the judg

ment, the findings of fact, and the court below’s failure to

require plaintiffs both to exhaust their administrative reme

dies, and obtain from the state courts a determination of

the constitutionality of the Texas law. The trial court

denied this motion on March 1, 1962 (R. 268), and on the

same date issued an opinion setting forth the basis for his

judgment in this case (R. 268).

From this judgment, appellants appeal to this Court (R.

294).

A R G U M E N T

I

Appellees were not required to exhaust the adminis

trative remedy provided by either Texas Law or School

Board Regulations prior to invoking the jurisdiction of

the court below.

Appellees, Negro citizens of the United States and

residents of Fort Worth, Texas, brought this suit on be

half of their children, and all members of the class simi

larly situated, to enjoin compulsory racial segregation in

public schools under the jurisdiction of the Fort Worth

Independent School District, and to secure compliance with

the Supreme Court’s decisions holding such segregation

unconstitutional. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483 (1954), 349 U. S. 294 (1955); Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1 (1958).

The appellants, notwithstanding deep convictions con

cerning the superiority of their dual school system, from

which statements the court below concluded “ that there

is no reasonable probability within the foreseeable future

8

of a voluntary change in the defendant’s policy as to

racial segregation” (R. 61), nevertheless strongly contend

in specification of errors 1, 2, 3, 4, and 11 (appellants’

brief, pp. 2-4) that the court below should not have en

tered its order without requiring appellees to exhaust their

administrative remedies.

It is appellants’ contention that because the complaint

does not allege that plaintiffs have sought individual re

assignments to particular schools by fully pursuing the

administrative procedures provided by the Fort Worth

Independent School District, or those provided by the

Texas pupil assignment law (Section 7, Article 2901a,

Vernon’s Annotated Civil Statutes), the plaintiffs are not

entitled to any relief in this action.

In support of this argument defendants rely principally

upon Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education,

358 U. S. 101 (1958), affirming on “ limited grounds” 162

F. Supp. 373, 384 (N. D. Ala. 1958), and the decision by

the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Carson v.

Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956).

It is submitted that the appellants’ argument is clearly

without merit, and has been plainly rejected by this Court

in cases decided subsequent to those mentioned above.

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370

(5th Cir. 1960); Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction,

272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959).

In the Mannings case the Court stated the issue presented

in the following manner (277 F. 2d at 372):

. . . Are the plaintiffs, in a class action in a school

segregation case, denied the right to have the trial

court enjoin a local board of education from con

tinuing to operate the local school system on a racially

segregated basis, solely because the individual plain

9

tiffs have not exhausted administrative remedies made

available to them to seek admission to certain desig

nated schools?

The Court decided the issue against the school board in

that case, concluding (277 F. 2d at 373):

Thus it is clear that the plaintiffs were not deprived

of their right to litigate over the basic question of

desegregation of the public school system, because of

their failure to apply for entry into specified schools.

The Court went on to observe that the plaintiffs were

entitled to “ the protection of a court order making certain

that the factor of race would not be a consideration in

the solution of [the] . . . many intangible tests” of the

pupil assignment law if they could sustain the allegations

of the complaint (277 F. 2d at 375).

The decision in the Shuttlesivorth case, supra, does not

support the argument that the existence of the pupil as

signment law is in itself a plan of desegregation or a

“ reasonable start toward full compliance” with the Su

preme Court’s decisions in Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483 (1954); 349 U. S. 294 (1955). The author

of that opinion (Judge Rives) made this plain in Gibson

v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763, 766 (5th

Cir. 1959).

Subsequent to Mannings, the Fourth Circuit specifically

expressed its agreement with that decision, Farley v.

Turner, 281 F. 2d 131, 132 (4th Cir. 1961); and has fre

quently indicated its disposition to appraise the validity

of a school system’s general procedures for the assignment

of pupils as distinct from the problems related to the as

signment of particular plaintiffs. Jones v. School Board

of the City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72, 76-77 (4th Cir.

10

1960); Hill v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 282

F. 2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960); Dodson v. School Board of City

of Charlottesville, 289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961). Recently,

the Fourth Circuit has apparently drawn even closer to

Mannings and Gibson. In Marsh v. County School Board

of Roanoke County, ------ F. 2d ------ (4th Cir., No. 8535,

June 12, 1962), the Court said:

Because the initial school assignments are made on a

racial basis, full compliance by the plaintiffs with

the transfer procedures cannot repair the discrimina

tions to which they have been and are subjected. In

view of the initial assignment system, the administra

tive procedures for transfer are, for the most part,

applied to Negroes seeking a desegregated education

and not to whites similarly situated. To insist, as a

prerequisite to granting relief against discriminatory

practices, that the plaintiffs first pass through the very

procedures that are discriminatory would be to require

an exercise in futility.

See also, Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke,

------F. 2 d ------- (4th Cir., No. 8534, May 22, 1962).

The Sixth Circuit in Northcross v. Board of Education

of City of Memphis,------ F. 2 d -------- (6th Cir., No. 14642,

March 23,1962) cert, denied 30 U. S. Law Week 3398 (June

25, 1962), saying that the Tennessee pupil assignment law

“ might serve some purpose in the administration of a school

system but it will not serve as a plan to convert a biracial

system into a nonracial one” , did not require the exhaustion

of administrative procedures provided by the act prior to

reversing a lower court’s refusal to grant injunctive relief

to restrain the operation of a biracial school system.

In Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960), this

Court had prior occasion to review a Texas case involving

11

the adequacy and validity of plans for desegregation of a

school system without reference to the applications of indi

vidual plaintiffs for admission to named schools. The

Court indicated its familiarity with the statute relied upon

by appellants (discussing it in another connection at 285

F. 2d 43, 48-50), but nevertheless proceeded to require that

a desegregation plan be implemented in Dallas, Texas.

Under the principles set forth in Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) and Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1 (1958), it is the duty of the courts in school desegre

gation cases to require local school authorities who are

maintaining segregation to develop arrangements for elimi

nating segregation as soon as practicable, and to require

them to “ devote every effort toward initiating desegrega

tion and bringing about the elimination of racial discrimina

tion . . . ” (358 U. S. at 7).

Clearly, these rules should apply with special force here

where appellants have not abandoned their dual school

system, and indeed contend that such policy may be in

definitely maintained without violating the constitutional

rights of appellees.

The School Board asserts in Specification of Error No. 9

that it does not rely on the separate-but-equal doctrine of

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896), and objects to

the trial court’s statement that (R. 283):

They attempted to justify their dual system under the

separate-but-equal doctrine formerly recognized by

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, as if it had never

been rejected by the Brown case.

Even if we accept the Board’s statement that the evi

dence concerning school construction for Negro and white

schools and equal salaries for Negro and white teachers

12

and other evidence of like character was offered to show

“upgrading [of] the quality of education of students, both

white and colored” (Appellants’ Brief p. 34), this affords

no ground for reversing the trial court’s judgment. Defen

dants are admittedly continuing the segregated dual system.

Under Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954),

and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958), this is inde

fensible.

The Board argues that the district court should have

stayed the proceedings pending state court determination

of applicable state law issues, presumably referring to the

Pupil Assignment Law (Appellants’ Brief pp. 18-19). The

argument is really that the plaintiffs should be required

to exhaust both the administrative remedies under the

statute and the state judicial remedies {Ibid.). However,

it is settled that exhaustion of state judicial remedies is

not a prerequisite to the grant of injunctive relief by fed

eral courts in school segregation cases. Carson v. Warticle,

238 F. 2d 724, 729 (4th Cir. 1956); Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S.

268 (1939); Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256, 262 (8th Cir.

1960). The School Board’s reliance upon R.R. Comm, of

Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 U. S. 496, 85 L. ed. 97, 61 S. Ct.

643 (1941), is plainly misplaced for this case does not call

for the interpretation of any state statute, for an injunc

tion against an ambiguous state law, or for any preliminary

guess as to the applicable state law. As indicated above,

the principal issue before the court was factual, namely,

whether the School Board continued to maintain a system

of assigning pupils to schools on the basis of race in dis

regard of Brown v. Board of Education, supra.

Finally, defendants contend in specification of error No.

11 (Appellants’ Brief, p. 35) that there was no basis for

the trial court’s finding that the school authorities would

not voluntarily abandon their dual school policy (R. 60-

13

61), and that therefore exhaustion of the administrative

procedures was futile (R. 64). But based on the testimony

of appellant school officials, particularly the Chairman of

the Board, the trial court could have reached no other con

clusion.

The Board, the Chairman testified (R. 158), defends

against this suit to abolish the dual system on two main

grounds: (1) Texas law requires such defense and penalizes

voluntary abandonment of the dual system by subjecting

school personnel to fines and imprisonment, and depriving

the school system of its accreditation; (2) it is the honest

conviction of the Board that the dual system will provide

the best education for both Negro and white pupils. On

such testimony the court below reasoned that exhaustion

of the administrative procedures could provide no adequate

remedy to appellees because of the fixed and definite policy

of the school authorities with respect to segregation and

because the provisions of Article 2900a, Texas Revised

Civil Statutes provide severe penalties upon any voluntary

departure from the dual policy. The court compared the

situation in this case with that in Virginia where the

Fourth Circuit reached a similar conclusion in City of New

port News v. Atkins, 246 F. 2d 325, 326 (4th Cir. 1957).

Moreover, even if the appellants were to change their

fixed policy and ignore Article 2900a upon reviewing ap

pellees’ individual transfer applications, even the granting

of such transfer requests could not provide appellees with

their requested relief, i.e., reorganization of the dual sys

tem on a unitary basis, since the pupil assignment pro

cedures are limited to the consideration of individual pupil

transfer requests. Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush,

242 F. 2d 156, 162 (5th Cir. 1957).

14

II

The Court granted appropriate relief for plaintiffs and

others similarly situated in ordering the defendants to

submit a plan of desegregation for the Fort Worth

school system.

In Specification of Errors Nos. 5 and 7 defendants argue

that the court erred by ordering that “ every7 colored child

in Fort Worth should be permitted to enter any white

school of his choice” , and in considering the case as a class

action (Appellants’ Brief p. 29).

Appellees submit that the order of the court below was

plainly proper. The order merely required that the defen

dants submit to the court a plan of desegregation consis

tent with the Brown decision. The defendants’ description

of the judgment is plainly fanciful, as a simple reading of

the judgment will demonstrate (R. 251-253).

The record conclusively demonstrates that the Fort

Worth school system is operated on a completely racially

segregated basis. The School Board has never denied this.

No “good faith” belief of school officials that maintenance

of the dual system is in “ the best interest of all the chil

dren” (R. 148) is a defense to plaintiffs’ claim for relief.

The Supreme Court has held that “ in the field of public

education the doctrine of ‘separate-but-equal’ has no place.”

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 495. This

Court has faithfully followed Brown from the start.

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156 (5th

Cir. 1957).

The School Board has not complied with Brown by merely

making a study of desegregation problems, Mapp v. Board

of Education of the City of Chattanooga, 295 F. 2d 617

(6th Cir. 1961), nor does the existence of a pupil assign

15

ment law, without more, constitute a desegregation plan.

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763, 766

(5th Cir. 1959). The practice of assigning pupils to schools

on the basis of separate Negro and white school zones has

been repeatedly and unequivocally condemned as uncon

stitutional. Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexan

dria, Va., 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960); Marsh v. County

School Board of Roanoke County, Va.,------ F. 2d ------- (4th

Cir. No. 8535, June 12, 1962); Green v. School Board of

City of Roanoke, Va.,------ F. 2 d ------ (4th Cir. No. 8534,

May 22,1962); Northcross v. Board of Education of City of

Memphis,------F. 2 d -------- (6th Cir. No. 14,642, March 23,

1962), cert, denied 30 U. S. Law Week 3398 (June 25, 1962).

Thus, there can be no doubt that in view of the Board’s

failure to discontinue the dual system based on race, the

order of the court below is appropriate. Boson v. Rippy,

275 F. 2d 850, 853 (5th Cir. 1960); Gibson v. Board of

Public Instruction, supra; Mannings v. Board of Picblic

Instruction, supra.

The opinion of the court below adequately deals with the

defendants’ objection to treating the case as a class action,

including the argument with reference to one of the par

ents’ testimony that he was bringing the suit only for his

own children. See the opinion below (R. 275-281).

The procedural aspects of the class action issue pose no

difficulty, for it is really the substantive issue as to what

relief may be granted that is really in dispute. The case

comes within Rule 23(a)(3), Federal Rules of Civil Pro

cedure, in that it involves a numerous class of persons (all

Negro pupils in the system); it is obviously impracticable

to bring them all before the court; and they are represented

by “ one or more members of the class.” The case involves

“ several” rights with common questions of law and fact

and a request for a common relief for all members of the

16

class, namely, an injunction against the system of segre

gation. The court below found that:

The case was fairly and aggressively prosecuted.

There was no indication that the plaintiffs were at

tempting to make a collusive sacrifice of the right of

other Negro school children. What in reality would

a mere direct statement by Flax that he was prose

cuting the suit for all the Negro children in the Fort

Worth school district have added to this record[?]

The type of action brought by the plaintiffs, ordi

nary pleadings and the evidence as a whole, justify

the court in determining in his discretion that the case

should be treated as a class action. Even if that deci

sion were incorrect, the defendants suffered no injury,

in view of the nature of relief to which plaintiffs were

entitled and the type of judgment entered (R. 280-

281).

It is well known that numerous school segregation cases

like this one have been litigated as class actions under

Rule 23(a)(3). See Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board,

242 F. 2d 156, 165 (5th Cir. 1957); Borders v. Rippy, 247

F. 2d 268 (5th Cir. 1957); Northcross v. Board of Educa

tion of City of Memphis, supra; Marsh v. County School

Board of Roanoke County, V a.,------ F. 2 d -------- (4th Cir.

No. 8535, June 12, 1962).

17

111

The District Court properly declined to convene a

three-judge Court under 28 United States Code Section

2281.

The appellant School Board’s claim that the district judge

erred in refusing to convene a three-judge court is not

supported by any citation of authority. The Board merely

asserts that the judgment “ effectively held the Texas

Statutes, Article 2900a and Article 2901a . . . [and the local

School Board’s transfer rules] to be invalid” (Appellants’

Brief p. 26, Specification of Error No. 6).

The District Court stated four grounds for its refusal

to convene a three-judge court, none of which has been

answered in appellants’ brief (R. 273-274). The Court held

that no three-judge court was required in that:

1. There was no request for an injunction enjoining

Articles 2900a and 2901a, relying upon School Board of

the City of Newport News v. Atkins, 246 F. 2d 325, 327

(4th Cir. 1957).

2. The complaint sought relief against a school board’s

policy of racial discrimination and this presented merely

a factual issue—thus three judges were not required even

though the policy originated in a state law, relying on

Beale v. Holcomb, 193 F. 2d 384 (5th Cir. 1951), and Wichita

Falls Junior College District v. Battle, 204 F. 2d 632 (5th

Cir. 1953).

3. The unconstitutional application of the laws made it

unnecessary to pass on the validity of the laws themselves,

see Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 162

F. Supp. 372 (N. 1). Ala. 1958), aff’d 358 U. S. 101 (1958),

18

and Ex parte Bransford, 310 U. S. 354, 84 L. ed. 1249, 60

S. Ct. 947 (1940).

4. Even if the validity of Articles 2900a and 2901a is

necessarily before the court, three judges were not neces

sary because the laws are patently and manifestly uncon

stitutional, citing Atkins v. School Board of City of Newport

News, 148 F. Supp. 430 (E. D. Va. 1957), aff’d 247 F. 2d 325

(4th Cir. 1957), and Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board,

138 F. Supp. 336; 138 F. Supp. 337 (E. D. La. 1956), aff’d

242 F. 2d 156 (5th Cir. 1957).

Initially, it must be observed that the School Board has

not pursued the correct remedy to challenge the district

judge’s refusal to convene a court of three judges. The

Board’s remedy, if any, is by application for a writ of

mandamus, rather than by an appeal, as the Supreme Court

plainly held in Stratton v. St. Louis, Southwestern R. Co.,

282 U. S. 10, 15-16, 75 L. ed. 135, 51 S. Ct. 8 (1930). The

Court held in Stratton that if a single district judge im

properly granted an injunction where three judges should

have been convened, no appeal would lie either to the

Supreme Court or to the Court of Appeals, and that the

only remedy was an application for a writ of mandamus.

The Stratton case apparently has continued vitality despite

the reluctance of appeals courts to apply it strictly.1 See

1 Various appeals court decisions sustaining appellate jurisdiction

on the three-judge court issue, where district judges have dismissed

complaints on the ground of lack of a substantiality of the federal

question, are at least formally distinguishable. Such decisions in

clude this Court’s opinion in Stuart v. Wilson, 282 F. 2d 539 (5th

Cir. 1960), and other cases collected in German v. South Carolina

State Port Authority, 295 F. 2d 491, 493-494 (4th Cir. 1961). Those

cases, unlike the instant case, did not involve attempting appellate

review of single judge opinions granting injunctive relief or refus

ing relief on grounds other than lack of substantiality of the con

stitutional question.

19

Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Cory. v. Rohan, 289 F. 2d

426, 429 (2nd Cir. 1961), where the court dismissed an

appeal for lack of jurisdiction, though stating a strong

view that three judges should have been convened. When

the District Court again refused to call three judges, the

Supreme Court reviewed the case and held that the District

Court should have done so. The Supreme Court implicitly

approved the Second Circuit’s determination that it lacked

jurisdiction to reverse the refusal to convene three judges,

though it observed that Stratton did not deprive circuit

courts of all power to guide district courts in such matters.

Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Gory. v. Eystein, 30 U. S. L.

Week 4599 (June 25, 1962).

Assuming arguendo that this Court has jurisdiction to

review appellants’ contentions, they are, nevertheless, with

out merit. That there would be no need for a three-

judge court to invalidate the local School Board’s trans

fer rules is plain since §2281 applies only to statewide

laws of general applicability and does not even include

municipal ordinances or state laws having only local ap

plication. Ex yarte Collins, 277 U. S. 565, 48 S. Ct. 585,

72 L. ed. 990 (1938); Cleveland v. United States, 323 U. S.

329, 332, 65 S. Ct. 280, 89 L. ed. 274 (1945). Actually, the

court below merely held the transfer procedures were an

inadequate remedy in light of the dual system of schools

based on race.

The District Court’s conclusion that Article 2900a

presents no substantial federal question is plainly correct

under prior decisions of this Court. This law7, which for

bids school authorities to desegregate schools unless the

electors of a district authorize it in an election, has been

repeatedly disregarded by this Court in cases similar to

this. See Boson v. Riyyy, 285 F. 2d 43, 45, note 11 (5th

Cir. 1960) and cases collected therein. Indeed, the appel

20

lants attempt no real defense of this law in their brief.

The Board apparently acknowledges that Article 2900a

affords it no defense (see appellants’ brief, pp. 23-24).

The Supreme Court recently stated that §2281 does not

require a three-judge court when “ prior decisions make

frivolous any claim that a state statute on its face is not

unconstitutional.” Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31, 7 L. ed.

2d 512, 514 (1962). See also, Turner v. Memphis, ------

U. S .------ , 7 L. ed. 2d 762 (1962). Any claim that Article

2900a can validly relieve the school authorities’ obligation

to desegregate public schools or prevent court enforcement

of this duty, is frivolous in light of Borders v. Rippy,

supra, and the other cases cited therein. Indeed, laws

of this genre have been uniformly held invalid. See James

v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E. D. Va. 1959); Aaron v.

McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark. 1959), aff’d

sub nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U. S. 197; Bush v. Orleans

Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp. 42, 188 F. Supp. 916

(E. D. La. 1960), aff’d 365 U. S. 569; Hall v. St, Helena

Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp. 649 (E. D. La. 1961),

aff’d 368 U. S. 515, 7 L. ed. 2d 521 (1962).

The argument that a three-judge court is required be

cause the defendants have invoked the Texas Pupil As

signment Law (Article 2901a) is equally insubstantial.

This Court’s decisions in Mannings v. Board of Public

Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960), and Gibson v.

Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959),

make it plain that the discriminatory administration of a

Pupil Assignment Law, such as the making of initial

assignments on the basis of race under a segregated dual-

racial system, can justify an injunction against the segre

gated system irrespective of the apparent validity of an

assignment law on its face. Any lingering doubts as to

21

the validity of this position were resolved by the United

States Supreme Court in June 1961, when it rejected an

argument which attacked the Mannings doctrine and was

similar to that made by the Board here. See Braxton v.

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Fla., un

reported order of March 1, 1961, refusing a three-judge

court (S. D. Fla., No. 4598-Civ-J), mandamus and prohibi

tion denied, sub nom. Board of Public Instruction of Duval

County, Fla. v. Hon. Bryan Simpson, 366 U. S. 957, 6

L. ed. 2d 1267, 81 S. Ct. 1944 (1961).

IV

Neither the plaintiffs’ motives in bringing the suit or

the fact that others are aiding plaintiffs in the expenses

of litigation are relevant.

The Board’s argument in connection with Specification of

Error No. 8 consists almost entirely of excerpts from the

transcript relating to one of the plaintiffs’ statements that

he received aid in the present lawsuit from the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People.2 The

Board has made no argument and cited no cases to estab

lish the relevance of this testimony to the merits of the

case.

It has been repeatedly held that a litigant’s motives in

bringing an action to protect his rights are irrelevant if

the facts bring him within the jurisdiction of the court.

Doremus v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 429, 434, 435,

2 For a judicial description of the activities of the N. A . A . C. P.

and the N. A . A. C. P. Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.,

see Judge Soper's opinion in N. A. A. C. P. v. Patty, 159 F. Supp.

503 (E. D. Va. 1958), vacated on ground of equitable abstention

sub nom. Harrison v. N. A. A. C. P., 360 U. S. 167, 3 L. ed. 2d

1152, 79 S. Ct. 1025.

22

96 L. ed. 475, 72 S. Ct. 394 (1952); Young v. Higbee Co.,

324 U. S. 204, 214, 89 L. ed. 890, 65 S. Ct. 594 (1945);

Wheeler v. Denver, 229 U. S. 342, 351, 57 L. ed. 1219, 33

S. Ct. 842 (1913); Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202, 204, 3

L. ed. 2d 222, 79 S. Ct. 178 (1958). The fact that others may

pay the expenses of litigation does not impair a party’s

standing, Wheeler v. Denver, supra, nor would even a

claim of champerty be relevant or an available defense on

the merits, Burnes v. Scott, 117 U. S. 582, 589-591, 29 L. ed.

991, 6 S. Ct. 865 (1886); Stark v. Brannan, 82 F. Supp. 614,

616, 617 (D. C. Cir. 1949), aff’d 185 F. 2d 871, 873 (D. C.

Cir. 1950), aff’d 342 U. S. 451, 96 L. ed. 497, 72 S. Ct. 433

(1952); Foremost Promotions v. Pabst Brewing Co., 15

F. R. D. 128, 130, 19 F. R. Serv. 26b.31, Case No. 4 (N. D.

111. 1953).

None of the matters argued by the School Board in this

connection afford any defense for the Board’s failure to

meet its constitutional obligations to bring about the elimi

nation of racial segregation in the school system under

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); 349

U. S. 294 (1955); and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958).

23

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, appellees respect

fully submit that the judgment of the district court should

be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

L. Clifford Davis

403 East 9th Street

Fort Worth, Texas

W. J. Durham

Universal Life Building

2600 Flora Street

P. 0. Box 641

Dallas, Texas

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

D errick A. B ell, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellees

la

A P P E N D I X

Transfer and Placement of Pupils to Schools Within an

Outside District, Transfer of Funds and Teachers

Article 2901a

Vernon’s Texas Civil Statutes

(Approved May 23,1957)

Section 1. The Legislature finds and declares that the

rapidly increasing demands upon the public economy for

the continuance of education as a public function and the

efficient maintenance and public support of the public school

system require, among other tilings, consideration of a more

flexible and selective procedure for the establishment of

units, facilities and curricula and as to the qualification

and assignment of pupils.

The Legislature also recognizes the necessity for a pro

cedure for the analysis of the qualifications, motivations,

aptitudes and characteristics of the individual pupils for

the purpose of placement, both as a function of efficiency in

the educational process and to assure the maintenance of

order and good will indispensable to the willingness of its

citizens and taxpayers to continue an educational system

as a public function, and also as a vital function of the

sovereignty and police power of the State.

Section 2. To the ends aforesaid, the State Board of

Education shall make continuing studies as a basis for

general reconsideration of the efficiency of the educational

system in promoting the progress of pupils in accordance

with their capacity and to adapt the curriculum to such

capacity and otherwise conform the system of public educa

tion to social order and good will. Pending further studies

2a

and recommendations by the school authorities the Legisla

ture considers that any general or arbitrary reallocation

of pupils heretofore entered in the public school system

according to any rigid rule of proximity of residence or in

accordance solely with request on behalf of the pupil would

be disruptive to orderly administration, tend to invite or

induce disorganization and impose an excessive burden on

the available resources and teaching and administrative

personnel of the schools.

Section 3. Pending further studies and legislation to

give effect to the policy declared by this Act, the respective

district and county Boards of School Trustees hereinafter

referred to as “ Local Boards,” are not required to make

any general reallocation of pupils heretofore entered in the

public school system and shall have no authority to make

or administer any general or blanket order to that end from

any source whatever, or to give effect to any order which

shall purport to or in effect require transfer or initial or

subsequent placement of any individual or group in any unit

or facility without a finding by the Local Board or authority

designated by it that such transfer or placement is as to

each individual pupil consistent with the test of the public

and educational policy governing the admission and place

ment of pupils in the public school system prescribed by this

Act.

Section 4. Subject to appeal in the respect herein pro

vided, each Local Board of School Trustees shall have full

and final authority and responsibility for the assignment,

transfer and continuance of all pupils among and within

the public schools within its jurisdiction, and may prescribe

rules and regulations pertaining to those functions. Subject

to review by the Board as provided herein, the Board may

exercise this responsibility directly or may delegate its

authority to the Superintendent or other person or persons

3a

employed by the Board. In the assignment, transfer or

continuance of pupils among and within the schools, or

within the classroom and other facilities thereof, the fol

lowing factors and the effect or results thereof shall be

considered, with respect to the individual pupil, as well as

other relevant matters: Available room and teaching capac

ity in the various schools; the availability of transportation

facilities; the effect of the admission of new pupils upon

established or proposed academic program; the suitability

of established curricula for particular pupils; the adequacy

of the pupil's academic preparation for admission to a

particular school and curriculum; the scholastic aptitude

and relative intelligence or mental energy or ability of the

pupil; the psychological qualification of the pupil for the

type of teaching and associations involved; the effect of

admission of the pupil upon the academic progress of other

students in a particular school or facility thereof; the effect

of admission upon prevailing academic standards at a par

ticular school; the psychological effect upon the pupil of

attendance at a particular school; the possibility or threat

of friction or disorder among pupils or others; the possi

bility of breaches of the peace or ill will or economic retalia

tion within the community; the home environment of the

pupil; the maintenance or severance of established social

and psychological relationships with other pupils and with

teachers; the choice and interests of the pupil; the morals,

conduct, health and personal standards of the pupil; the

request or consent of parents or guardians and the reasons

assigned therefor.

In considering the factors and the effect or results thereof

the Board or its agents shall not consider and shall not use

as an element of its evaluation any matter relating to the

national origin of the pupil or the pupil’s ancestral language.

Local Boards may require the assignment of pupils to

any or all schools within their jurisdiction on the basis of

4a

sex, but assignments of pupils of the same sex among

schools reserved for that sex shall be made in the light of

the other factors herein set forth.

Section 5. Local Boards may, by mutual agreement, pro

vide for the admission to any school of pupils residing in

adjoining districts whether in the same or different counties,

and for transfer of school funds or other payments by one

Board to another for or on account of such attendance.

Section 6. Subject to the provisions of law governing

the tenure of teachers, Local Boards shall have authority

to assign and reassign or transfer all teachers in schools

within their jurisdiction.

Section 7. A parent or guardian of a pupil may file in

writing with the Local Board objections to the assignment

of the pupil to a particular school, or may request by peti

tion in writing assignment or transfer to a designated school

or to another school to be designated by the Board. Unless

a hearing is requested, the Board shall act upon the same

within thirty (30) days, stating its conclusion. If a hearing

is requested the same shall be held beginning within thirty

(30) days from receipt by the Board of the objection or

petition, at a time and place within the school district

designated by the Board.

The Board must conduct such hearing and such hearing

shall be final on behalf of the Board.

In addition to hearing such evidence relevant to the

individual pupil as may be presented on behalf of the

petitioner, the Board shall be authorized to conduct in

vestigations as to any objection or request, including ex

amination of the pupil or pupils involved, and may employ

such agents and others, professional and otherwise, as it

may deem necessary for the purpose of such investigations

and examinations.

5a

Section 8. Any other provisions of law notwithstanding,

no child shall be compelled to attend any school in which

the races are commingled when a written objection of the

parent or guardian has been filed with the Board, if such

be the decision of the Local Board. If in connection there

with a requested assignment or transfer is refused by the

Board, the parent or guardian may notify the Board in

writing that he is unwilling for the pupil to remain in the

school to which assigned, and the assignment and further

attendance of the pupil shall thereupon terminate; and

such child shall be entitled to such aid for education as

may be authorized by law.

Section 9. The action of the Board shall be final except

that in the event that the pupil or the parent or guardian,

if any, of any minor or, if none, of the custodian of any

such minor shall, as next friend, file exception before such

Board to the final action of the Board as constituting a

denial of any right of such minor guaranteed under the

Constitution of the United States, and the Board shall not,

within fifteen (15) days reconsider its final action, an ap

peal may be taken from the final action of the Board, on

that ground alone, to the District Court of the county

in which the School Board is located by filing with the

Clerk within thirty (30) days from the date of the Board’s

final decision a petition stating the facts relevant to such

pupil as bearing on the alleged denial of his rights under

the Constitution, accompanied by bond with sureties ap

proved by the Clerk, conditioned to pay all costs of appeal

if the same shall not be sustained.

Section 9A. Nothing in this Act shall affect any action

heretofore taken by any school district in this State

covering the subject matter of this Act.

Section 10. The provisions of this Act are severable,

and if any section or provision of this Act shall be held

6a

to be in violation of the Constitution of Texas or of the

United States, such decision shall not affect the validity

or enforceability of the remainder of this Act.

Separate Schools

Article 2900a

Vernon’s Texas Civil Statutes

(Approved May 23, 1957)

Section 1. That no board of trustees nor any other

school authority shall have the right to abolish the dual

public school system nor to abolish arrangements for trans

fer out of the district for students of any minority race,

unless by a prior vote of the qualified electors residing

in such district the dual school system therein is abolished.

Section 2. An election for such purposes shall be called

only upon a petition signed by at least twenty per cent

(20%) of the qualified electors residing in such district.

Such petition shall be presented to such office or board

now authorized to call school elections. Such an election

may be set for the same date as the school trustee elec

tion in that district, if such petition is filed within ninety

(90) days to such date, otherwise the official or board shall

call such an election within sixty (60) days after filing of

such petition. The election shall be conducted in a manner

similar to that for the election of school trustees. No

subsequent election on such issues shall be called within

two (2) years of a prior election held hereunder.

Section 3. School districts which maintained integrated

schools for the 1956-1957 school year shall be permitted

to continue doing so hereafter unless such system is

abolished in accordance with the provisions of this Act.

7a

No student shall be denied transfer from one school to

another because of race or color.

Section 4. Any school district wherein the board of

trustees shall violate any of the above provisions shall

be ineligible for accreditation and ineligible to receive

any Foundation Program Funds during the period of time

of such violation. Any person who violates any provision

hereof shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and shall be fined

not less than One Hundred Dollars ($100) nor more than

One Thousand Dollars ($1,000).