Brown v. Ramsey Brief for Appellants and Joint Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Ramsey Brief for Appellants and Joint Appendix, 1956. 8ffb70b1-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/478fa65a-c04a-4ae1-8a9e-540f54359821/brown-v-ramsey-brief-for-appellants-and-joint-appendix. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

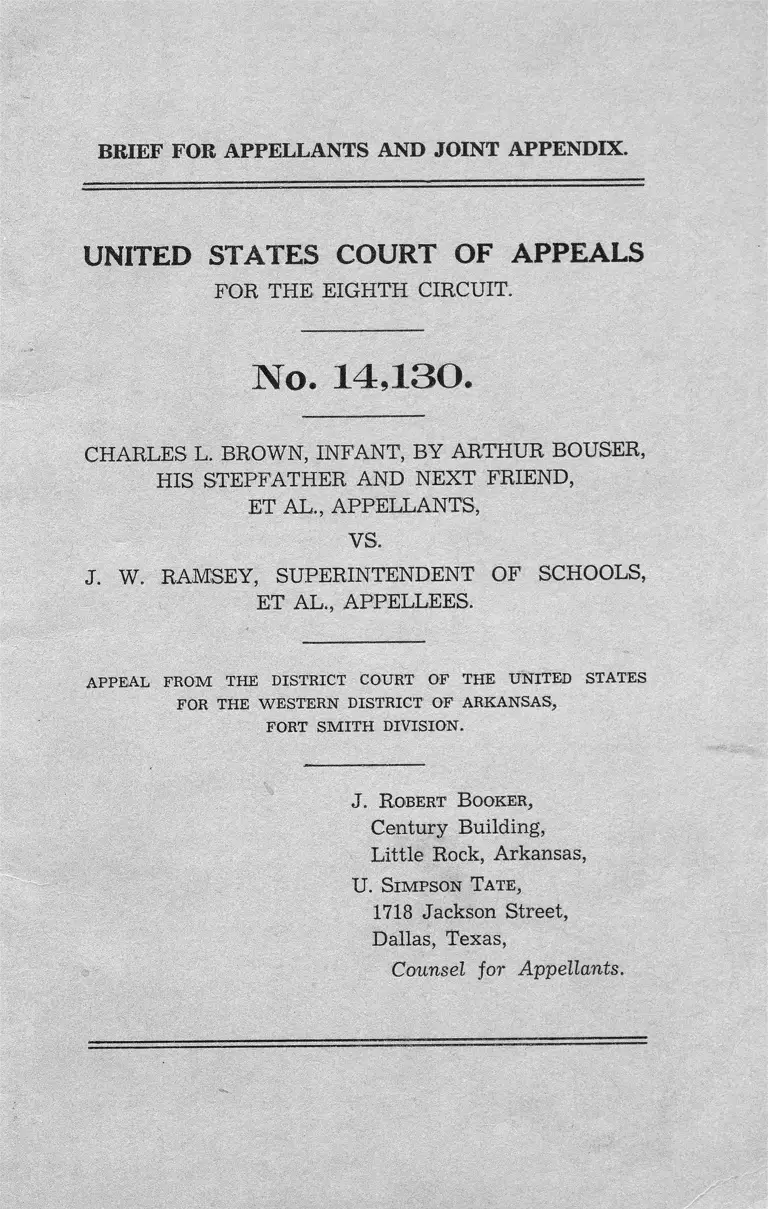

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS AND JOINT APPENDIX.

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT.

No. 14,130.

CHARLES L. BROWN, INFANT, BY ARTHUR BOUSER,

HIS STEPFATHER AND NEXT FRIEND,

ET AL., APPELLANTS,

VS.

J. W. RAMSEY, SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS,

ET AL., APPELLEES.

a p p e a l f r o m th e d ist r ic t c o u r t of th e u n it e d s t a t e s

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS,

FORT SMITH DIVISION.

J, R o b e r t B o o k er ,

Century Building,

Little Rock, Arkansas,

U. S im p s o n T a t e ,

1718 Jackson Street,

Dallas, Texas,

Counsel for Appellants,

SUBJECT INDEX

Jurisdictional Statement------------------------------------------- 1

Statement of Case__________________________________ 3

Statement of Errors_______________________________ 4

Points Relied Upon in Argument____________________ 6

Argument-------------- 8

I. Plaintiffs were entitled to a summary judgment

of June 13, 1949, when their motion for sum

mary judgment was heard by the court------------ 8

II. The Fort Smith Junior College was established

as a part of the Fort Smith public school sys

tem and has been operated and maintained since

its establishment out of public funds--------------- 9

III. The plaintiffs and others similarly situated on

whose behalf they sued have been discriminated

against by defendants in courses offered at the

Lincoln High School for Negroes as compared

to those offered in the Junior and Senior High

Schools and the Junior College for white

scholastics___________________________________ 15

IV. The plaintiffs and those similarly situated on

whose behalf they sued have been discriminated

against in the per capita expenditures made in

capital invested in lands, buildings and equip

ment for educational purposes, and in operat

ing expenses of public schools in the district----- 25

II Index

T a b le , of C ase s

American Insurance Co. vs. Gentile Bros., 109 F. 2d

732 _____________________________________________ 8

Blood vs. Fleming, 161 F. 2d 292------------------------ 9

Creel vs. Lone Star Defense Corp., 171 F. 2d 964--------- 8

Engle vs. Aetna Life Insurance Co., 139 F. 2d 469------ 9

Fletcher vs. Kris, 120 F. 2d 809-------------------------------- 9

Gaines vs. Canada, 59 S. Ct. 232------------------------------ 19, 21

Gassifier Mfg. Co. vs. Ford Motor Co., 1 F. R. D. 104— 8

Loan Association vs. Topeka, 87 U. S. 655-------- ------- 15

McCabe vs. A., T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151, 305

U. S. 339_______________ - _______________________ 19

Mitchell vs. U. S., 63 S. Ct. 873____________ __ _____ 19

Moore vs. State, 76 Ark. 197, 88 S. W. 881--------------- 15

Reid Gas Engine Co. vs. Lewellyn, 42 F. Supp. 895------ 9

Sipuel vs. Board of Regents of Okla., 332 U. S. 631------ 21

Town River Junction vs. Maryland Casualty Co., 110

F. 2d 278_______________________________________ 9

Vitzoi vs. Balboa S. S. Co., 69 F. Supp. 286--------------- 9

Westminster School District vs. Mendz, 161 F. 2d 993-— 19

S t a t u t e s

Judicial Code, Section 24 (1 )_______________________ 2

Judicial Code, Section 24 (14)--------------------------------- 2

Pope’s Digest, Arkansas Laws, Section 11535------------ 3

Rule 56, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure--------------- 8

Rule 73, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure--------------- 2

Title 8, United States Code, Sections 41 and 43--------- 2

Title 28, United States Code, Section 225____________ 2

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT.

No. 14,130.

CHARLES L. BROWN, INFANT, BY ARTHUR BOUSER,

HIS STEPFATHER AND NEXT FRIEND,

ET AL., APPELLANTS,

VS.

J. W. RAMSEY, SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS,

ET AL., APPELLEES.

APPEAL FROM THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS,

FORT SMITH DIVISION.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS AND JOINT APPENDIX.

Appellants respectfully submit the following brief in

support of Appellants’ affirmative position that the judg

ment appealed from should be reversed,

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT,

The appellants appeal from a judgment entered

against them in favor of appellees, defendants below, in

the District Court of The United States for the Western

2

District of Arkansas, Fort Smith Division, in Civil Action

numbered 798 on the 19th day of November, 1949, by the

District Court of the United States for the Western Dis

trict of Arkansas, Fort Smith Division, after hearing by

the Court.

The District Court of the United States, for the West

ern Division of Arkansas, had jurisdiction of the cause,

under the Judicial Code, Section 24(1) (28 United States

Code, Section 41(1)), this being a suit in equity which

arose under the Constitution and Laws of the United States,

viz., the Fourteenth Amendment of said Constitution and

Sections 41 and 43 of Title 8 of the United States Code,

and under Section 24(14) of the Judicial Code (28 United

States Code, Section 41 (14)).,. this being a suit in equity au

thorized by law to be brought to redress the deprivation

under color of law, statute, regulation, custom and usage

of a state rights, privileges and immunities secured by

the Constitution of the United States, viz., the Fourteenth

Amendment to said Constitution, and of rights secured by

laws of the United States providing for equal rights of

citizens of the United States and of all persons within the

jurisdiction of the United States, viz., Sections 41 and 43

of Title 8 of the United States Code.

This Court has jurisdiction to review the judgment

under Title 28 of the United States Code, Section 225, and

under Rule 73 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The pleadings, which show the existence of juris

diction, are the complaint, the amended complaint and

answer filed herein (R. 2, 47 and 43).

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

The plaintiffs herein, are all minor citizens of the

United States and residents domiciled in Arkansas and

within the Fort Smith Special School District, who are

entitled to attend the public schools of Fort Smith, Arkan

sas. Under the laws of Arkansas it is the duty of School

Directors to: “Establish separate schools for white and

colored persons,” Pope’s Digest, Section 11535. All of the

plaintiffs herein are members of the Negro or colored race,

and as such are forced and compelled to attend such

schools as are designated for them by the School Directors

as schools for Negroes, on a segregated basis. On Decem

ber 10, 1948, plaintiffs filed their original complaint in

which they contended that certain discriminations had

been practiced against them by the Defendant Board of

School Trustees in providing educational opportunities,

privileges and advantages, because of the race and color of

plaintiffs. An Amended complaint was filed substituting

certain parties as plaintiffs. The Court granted defend

ants’ motions for sixty days (60) extension of time in

which to answer. In February, 1949, Defendants filed a

motion for a more definite statement. In March, 1949,

plaintiffs filed their Bill of Particulars and at the same

time filed their Motion for Summary Judgment, with

affidavit attached and an Interrogatory. Defendants filed

their answer to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment

with affidavits attached. The Motion for Summary Judg

ment was heard on June 13, 1949, and dismissed by the

Court without any argument or motion by the defendants.

The cause came on for trial on November 9, 1949, and

Plaintiffs’ complaint was dismissed upon a finding of fact

by the Court that no discrimination with respect to plain

tiffs existed and for want of equity, from which judgment

and decree, this appeal is respectfully taken.

4

STATEMENT OF ERRORS.

1. The Court erred in over-ruling plaintiffs’ motion for

summary judgment.

2. The Court erred in its Findings of Fact in the following

instances:

(2) The Fort Smith Junior College is supported and

maintained from tuition and fees paid by the

students enrolled therein, and not from public tax

funds.

(13) The allocation of monies to the schools operated for

Negro children was made by the Directors in good

faith and with the intention of preserving a con

dition of substantial equality between the Negro

and white schools.

(15) The Lincoln High School in which the standard six

high school grades are taught affords the students

therein enrolled substantially the same educational

advantages enjoyed by the white students enrolled

in the junior and senior high schools. Both the

Lincoln High School and the Senior High School

enjoy equal standing in the North Central Associa

tion of Colleges and Secondary Schools, and

students from either school can enroll in any mem

ber college or university of said North Central

Association without any scholastic deficiencies.

(16) The Physical Education Department of the Lincoln

High School is comprehensive in scope, both for

male and female students. A woman teacher is

provided for the girls’ physical education classes

and a man teacher is provided for the boys’

classes. The equipment for these classes is left

largely to the respective instructors, and all requisi

tions for such equipment for the physical educa

tion department have been promptly filled by the

5

Board of Directors. The uncontradicted evidence

shows the Defendants able and willing to furnish

adequate athletic equipment for the use of the

students of Lincoln High School upon request and

requisition of the principal and faculty of that

school.

(18) Considered as a whole the buildings and other

physical facilities provided for the Negro school

children of the Defendant District are not inferior

to the buildings and other physical facilities pro

vided for the white children of the District.

(19) The buildings and other physical facilities which

are at the Lincoln High School, upon completion

of the buildings and new installations now almost

ready for occupancy and use, will be superior to

the buildings and appurtenant physical facilities

at the Junior High School and will be on a sub

stantial equality with the combined Junior and

Senior High School buildings and appurtenant

physical facilities.

(20) The courses of study made available to the students

of the Lincoln High School are substantially equal

to the courses of study made available to the

students of the Junior and Senior High Schools.

(21) There is no discrimination, existing or imminent,

against the children of the Negro schools of the

Defendant District in the matter of curriculum or

courses of study.

(22) There is no discrimination, existing or imminent,

against the children of the Negro schools of the

Defendant District in the matter of building and

appurtenant physical facilities.

(23) There is not in existence or imminent any policy,

custom or usage in the Special School District of

Fort Smith, Arkansas, under which the Negro

school children of the District are discriminated

6

against in the favor of the white children of

the District.

3. The Court erred in its Conclusions of Law in the fol

lowing respects:

(3) With reference to the Fort Smith Junior College

the Plaintiffs have been denied no rights or

privileges guaranteed to them by the Federal or

State Constitutions or by Federal or State laws.

(5) The plaintiffs have failed to sustain the allegations

of their complaint.

(6) A decree should be entered dismissing the com

plaint for want of equity.

4. The decree and judgment of the Court is contrary to

the evidence.

5. The decree and judgment of the Court is contrary to the

the weight of the evidence.

6. The decree and judgment of the Court is contrary to the

law in such cases made and provided.

7. The Court erred in dismissing the complaint of plaintiffs

for want of equity.

POINTS RELIED UPON IN ARGUMENT.

I.

Plaintiffs were entitled to a summary judgment of

June 13, 1949, when their motion for summary judgment

was heard by the court.

II.

The Fort Smith Junior College was established as a

part of the Fort Smith Public School System and has been

operated and maintained since its establishment out of

public funds.

7

III.

The plaintiffs and others similarly situated on whose

behalf they sued have been discriminated against by de

fendants in courses offered at the Lincoln High School for

negroes as compared to those offered in the Junior and

Senior High Schools and the Junior College for white

scholastics.

IV .

The plaintiffs and those similarly situated on whose

behalf they sued have been discriminated against in the

per capita expenditures made in capital invested in lands,

buildings and equipment for educational purposes, and in

operating expenses of public schools in the district.

8

ARGUMENT.

I.

Plaintiffs were entitled to a summary judgment of

June 13, 1949, when their motion for summary judgment

was heard by the court.

On June 13, 1949, when the Plaintiffs’ Motion for

Summary Judgment was heard by the Court, the cause had

been pending for six months and three days. The record

then before the Court consisted of plaintiffs’ amended com

plaint, defendants’ motion for a More Definite Statement,

Plaintiffs’ Bill of Particulars, Plaintiffs’ Motion for Sum

mary Judgment, Plaintiffs’ Interrogatory, Defendants’

Answer to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatory, Defendants’ Answer

to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment and Plain

tiffs’ and Defendants’ Affidavits attached to their Motion

for Summary Judgment and Answer thereto.

Appellants contend that the record as then made pre

sented no material dispute as to facts in the cause and that

Plaintiffs were entitled to a ruling by the Court on the

record as it then stood, that is on the pleadings, deposi

tions and supporting affidavits then before the Court.

American Insurance Co. v. Gentile Bros., 109 F. 2d

732.

Creel v. Lone Star Defense Cory., 171 F. 2d 964.

The purpose of Rule 56, Federal Rules of Civil Pro

cedure is to promptly dispose of causes where there is no

material dispute as to fact.

Grassifier Mfg. Co. v. Ford Motor Co., 1 F. R. D.

104.

9

The Rule intends to provide against vexation and de

lay which comes from formal setting for trial in those

cases where there is no material issue of fact.

Blood v. Fleming, 161 F. 2d 292.

It is intended for a party to pierce the allegations of

fact in the pleadings and obtain relief by Summary Judg

ment where the facts set forth in detail in affidavits, dep

ositions and admissions on file show that there are no

genuine issues of facts to be tried.

Engle v. Aetna Life Insurance Co., 139 F. 2d 469,

472.

Fletcher v. Kris, 120 F. 2d 809.

Vitzoi v. Balboa S. S. Co., 69 F. Supp. 286.

The Summary Judgment Rule contemplates that the

Judge will take the pleadings as they have been shaped to

see what issues of fact they make, and consider the deposi

tions, and admissions on file, together with the affidavits

to see if any such issues are real and genuine. If they are

not, judgment is given without further delay.

Town River Junction v. Maryland Casualty Co.,

110 F. 2d 278, 283.

Reid Gas Engine Co. v. Lewellyn, 42 F. Supp. 895.

Appellants, submit that Plaintiffs below should have

had judgment then on the record then before the Court.

II.

The Fort Smith Junior College was established as a

part of the Fort Smith Public School System and has been

operated and maintained since its establishment out of pub

lic funds.

The Fort Smith Junior College was established by the

Fort Smith Special School District and is operated by the

Board of Directors of the Fort Smith Special School Dis

10

trict (See Answer to Interrogatory 1) (R. 36 and 372). The

Fort Smith Junior College is operated in the Senior High

School Building (R. 211), as testified to by Dr. J. W.

Ramsey, Superintendent of Public Schools in Fort Smith,

Arkansas. Dr. Ramsey testified that he derives his entire

income from the Fort Smith Special School District and

that he is president of the Fort Smith Junior College (R.

212); that upon his recommendation teachers are hired for

the Senior High School and that some of these teachers are

used part time and some full time at the Junior College

(R. 212); that it is a part of his duties to plan the cur

riculum of all schools under his supervision (R. 212);

that he indirectly plans the courses offered at the Junior

College and that he has authority to approve the courses

offered at the Fort Smith Junior College (R. 212); that

the tuition at the Fort Smith Junior College is recommended

by him and the Board of Directors of the Fort Smith

Special School District upon his recommendation de

termines what the tuition at the Fort Smith Junior College

shall be (R. 212).

Dr. Ramsey, Superintendent of Schools at Fort Smith

was questioned by Attorney for Plaintiffs below:

Q. Now, Dr. Ramsey, there are certain expenses in

cident to the operation of the Junior College, such

as providing heat, and light and telephone service,

janitorial service and so on. Who pays the light bill

at the Junior College?

A. The light bill and all of the operating expenses

of the Junior College are paid along with the same ex

penses for the High School, that is, on the assumption

that the building is there; it has to be maintained and

operated, regardless of the occupancy of it and in

that way—this is an indirect way of answering your

question, but these expenses are paid as part of the

high school (R. 213).

11

Q. Do you keep your revenue from the Junior Col

lege in a separate account?

A. All of our funds are co-mingled from all sources,

but a separate ledger account is kept for each of the

schools, including the Junior College (R. 213).

Dr. Ramsey further testified that Mr. Elmer Cook is

the Dean of the Junior College, and that Mr. Cook works

under his supervision and that Mr. Cook was appointed

on his recommendation (R. 213); that there is operated

under his supervision in Fort Smith a Junior High School,

a Senior High School and a Junior College for white scho

lastics (R. 213).

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 71 shows that for the years

1932-33 and 1942-43 to and including 1947-48 the Fort

Smith Junior College had an operating loss of $10,836.03

(Exhibit 71, following R. 228), in answer to question by

Attorney for Plaintiffs below, Dr. Ramsey denies that

there was a shortage, but he does not deny that if there

were one, it was paid out of the general public school

fund (R. 226).

In answer to Interrogatory 4, Dr. Ramsey admits that

Negro children are not admitted to the Fort Smith Junior

College, and in Interrogatory 4b, he further admits that

there is no Junior College in connection with the Lincoln

High School for Negroes (R. 36 and 373).

Testifying for defendants, Dr. Ramsey testified that

the construction of the Junior College-Stadium building

cost $150,000 of which $67,000 was a grant from the Fed

eral Works Administration and $83,000 was received from

the bond issue floated by the Fort Smith Special School

District (R. 347).

On cross examination of Mr. Raymond Orr, President

of the Board of Directors of the Fort Smith Special School

12

District, Mr. Orr was questioned and he answered as fol

lows:

Q. During the time you have been a member of the

school board, various bills have been presented to and

paid by the Fort Smith Board for the Fort Smith

Junior College, have they not?

A. The utility bills for the Senior High School, which

in turn, houses the Junior College.

Q. And the salaries also are paid by the Fort Smith

Special School District?

A. Which salaries?

Q. Salaries for the Junior College.

A. Yes.

Q. And the books for the library for Junior College

have also been paid for by the Fort Smith Special

School District, have they not?

A. I suppose they have. I cannot answer that exactly

(R. 260).

On re-direct examination Mr. Orr testified that salaries

and expense at the Junior College were paid out of the

general funds, and he continued:

Those of us on the board have known all the way

through at least I have since my time, that if we had

spent more than the tuition brought in we would

have been subject and vulnerable to attack from any

taxpayer that desired to raise the issue (R. 261).

Then there followed this question by defendants’ attorney:

Q. Isn’t it a fact that the school board has seen to it

at all times that the income from tuition paid by

students of the Junior College paid all the bills?

A. It is sufficient and has been to pay the out of

pocket cost (R. 261).

Now reading this question of Defendants’ attorney and

Mr. Orr’s answer in connection with the question by plain

13

tiffs’ attorney (R. 226) as to how the shortage of $10,-

836.03 which had arisen in the Junior College from 1933 to

1948 had been paid, and Dr. Ramsey’s answer thereto, a

complete picture of deliberate juggling of accounts pre

sents itself.

Q. Now, was that paid out of the general school fund,

sir, that difference?

A. The college during that period did not operate at

a loss. When these figures or expenses are considered

as applicable to Junior College—we paid the salaries

of the personnel, which would be a dean, part of the

time and a clerk part of the time. For a good many

years in this period the college operated on a much

less pretentious basis, I would say, than it is at pres

ent. There was no person in charge as a dean or

there was no additional secretaries—all operated out

of the principal’s office. Therefore, there was no

charge additional for that, because his salary was paid

to operate the school and there was no extra expense

incurred. So, the expenditures for the dean during

the period of this 17 years here that we had a dean,

the clerk, the salaries of the teachers, plus the actual

expenditures for library books, instruction materials,

any other incidental expense directly chargeable to

the Junior College, those four items I have men

tioned—well, exactly two; salaries of personnel and

direct instruction expenses, assuming that they were

only expenses that were incurred over and above what

would have been incurred, regardless of the Junior

college, putting that against the gross income in the

way of tuitions, there was a profit rather than a loss

(R. 227).

Thus the record disclosed that there were deliberate

manipulations of the accounts of the Junior College to

make them show a profit from tuition. But be that as it

may, the fact that the tutition from the college was put

into the general fund as was all other tuition paid as was

14

testified to by Dr. Ramsey (R. 213 and 357), and all of the

bills and expenses of the Junior College were paid out of

the same fund, it is of no significance that the income

from tuition did or did not exceed expenses, the Junior

College was operated at public Expense. Arkansas Stat

utes, 1947—Title 80, Education, Chapter 10, District Fi

nances, Section 1002—Revenue and Non-revenue Receipts

defined:

The revenue receipts of a school district shall be

defined as those receipts that do not result in increas

ing school indebtedness or in depleting school property.

Specifically they shall be defined as follows:

(2) The net proceeds from local taxes collected

during the year 1949 plus forty percentum (40%) of

the proceeds of local taxes which are not pledged for

debt service collected in 1950.

(3) The net proceeds from all other funds placed

to the credit of the school district during the fiscal

year from regular revenue sources, including tuition

receipts, fees, etc.

Non-revenue receipts of a school district shall be

defined as those receipts which must be met at some

future date or which change the form of an asset from

property to cash and therefore decrease the amount

and value of school property. Specifically they con

sist of proceeds of a bond sale, payments of losses on

an insurance policy, receipts from the sale of property,

etc. Non-revenue receipts shall not be considered as

revenue for current operating or maintenance pur

poses.

The Fort Smith Junior College is clearly a public in

stitution in that it was created by the Board of School

Trustees, it has always been housed in public school prop

erty, its teachers and all of its expense are paid out of the

general school funds, tuitions collected are deposited in

15

general school account. This being true it is of no im

portance that the tuition does or does not exceed the ex

penses, it is none-the-less a part of the public school system.

It is the general rule that a municipal corporation may

not issue bonds or assume a debt to aid in the establish

ment of a private corporation.

Loan Association v. Topeka, 87 U. S. 655.

It is the law in Arkansas that public funds may not be

applied to other than public purposes.

Moore v. State, 76 Ark. 197, 88 S. W. 881.

III.

The plaintiffs and others similarly situated on whose

behalf they have sued have been discriminated against by

defendants in courses offered at the Lincoln High School

for Negroes as compared to those offered in the Junior and

Senior High Schools and the Junior College for white

scholastics.

Professor C. M. Greene, Principal of the Lincoln High

School for Negroes at Fort Smith, Arkansas, testified on

direct examination, as an adverse witness for plaintiffs

that he was principal of the said school and that he had

been so employed for seven years (R. 110); that his school

does not now and will not in June, 1950, be able to issue

certificates of graduation to its students in commercial

training (R. 110). Such certificates are issued by the

Senior High School for white children. He further testi

fied that as of the day of trial, his school had no function

ing shop. He was questioned and gave answers as follows:

Q. In your trade shop, Mr. Greene, will you tell the

Court what equipment you have in that shop as of

today?

16

A. We haven’t any equipment in the new building

now.

Q. You have no equipment for teaching shop as of

today?

A. The building hasn’t opened yet (R. 111).

He also testified that there was no stadium in connection

with his school (R. 112); that there was no swimming pool

(R. 112).

Though Mr. Greene testified that his school had a

band, when shown Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 13 which is a picture

of the Band Room at the Senior High School for white

persons, and asked if similar equipment was provided in

his school, he answered in the negative (R. 113). He fur

ther said that his school had no equipment similar to that

shown in Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 14, which is the Music Room

at the Junior High School for white persons (R. 113).

When he was shown pictures of the Metal Trades shop at

the white high school, Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 19, and asked

if he had similar equipment in his school he replied, “We

do not” (R. 113). He further testified that the Lincoln

school had no auditorium similar to the one at the Senior

High School for White (R. 114), nor such as was shown in

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 31, which is the auditorium at the

Junior High School (R. 114). He admitted that the

Lincoln High School for Negroes did not on the date of trial

give courses in Spanish, Latin, Trigonometry, Diversified

Occupations, Sign painting, dramatics, costume jewelry

making, pewter work (R. 131), commercial art, oil and

water colors, commercial law, consumer education, Archi

tectural screening (R. 131), Distributive Education, Journal

ism, Accounting II and III (R. 132), Commercial Geography,

Algebra III, Salesmanship (R. 132). All of the above

courses are offered at the Senior High School for white

pupils (See Schedule of Courses at Senior High School

(R. 229, and Courses at Lincoln High School (R. 353)).

17

In his answer to Interrogatory 12 (R. 375) Dr. Ramsey,

Superintendent of Fort Smith Schools admitted that the

following courses were not offered at the Lincoln High

School for Colored: Accounting, Band, Business Law,

Commercial Law, Chemistry, Distributive Education,

Journalism, Latin, Linotyping, Printing press operation,

Metal Trades, Office Machines, Physics, Spanish, Short

hand, and Typing all of which are offered at the Senior

High School. Dr. Ramsey contended that Commercial

Geography was taught, but Mr. Greene testified that the

course was not taught (R. 132). Dr. Ramsey testified that

in the Junior College the following Courses were taught:

Art 13b, Business Law, Biology 13b; Band Music 13b; Ac

counting 13b-14b; Chemistry 13b; English 13b-14b; French

13b; History 13b-14b; International Relations 13b; Journal

ism 14b; Economics 13b-14b; Mathematics 13b-14b; Office

Machines 14b; Psychology 13a; Typewriting 13b-14b;

Shorthand 13b-14b; Production Printing Voice 13b-14b;

Violin 13b; Spanish 13b; and Swimming 13b (R. 373); and

that Negroes were not permitted by the defendant board

of education to attend said Junior College (R. 373), and

that no Junior College facilities were provided in con

nection with the Lincoln High School (R. 373 and 374) .

Professor A. H. Miller, the Shop Teacher at Lincoln

High School testified on Direct Examination, as an adverse

witness for Plaintiffs that he was Industrial Arts In

structor (R. 171) and that Industrial Arts Courses are ex

ploratory courses, devoted to one hour of teaching daily

while Trade Courses are taught for three hours per day

and they lead to trades for employment purposes (R. 171).

Mr. W. E. Hunzicker, Shop Teacher at the Senior

High School for White persons, testified as an adverse wit

ness for plaintiffs. After having identified Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit 19 as a true representation of the Machine Shop at

18

the Senior High School for white persons, he said that his

school offered courses in Industrial or vocational trades;

that such courses were strictly specific courses designed

to train a boy as an advanced learner in that field. This

embraces three periods per day in Trades and one period

to related trade information. He further testified that

industrial arts (such as is given at Lincoln) is part of

general education; they are exploratory or finding courses

he said (R. 182). They are feeders for trade courses.

To the following question, Mr. Hunzicker replied:

Q. Now, a young student who finished your course

would be superior in training, experience and equip

ment to a person who had finished the industrial arts

course, wouldn’t he?

A. We hope that he is, yes, sir.

Mr. Elisco Sanchez, Printing Teacher in the Fort

Smith Senior High School for white pupils, testified that

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 17. was a true representation of his print

shop at the Senior High School (R. 191), and identified

certain presses and machines therein, none of which are

provided for Negroes. He further testified that in his

department industrial arts and trade printing are taught

(R. 193).

Mr. Tom Traw, Woodwork Teacher at the Junior High

School testified that in woodwork in the Junior High

School only industrial arts are taught (R. 197). So it is

that the shop course in the Junior High School is the same

as the Shop course at the Lincoln High School, see testi

mony of Mr. A. H. Miller, Industrial Arts teacher at Lin

coln High School (R. 171), who testified that he taught

only industrial arts; that he was not equipped to teach

metal trades; that the machinery in his department was

in poor repairs (R. 173); that their emphasis had been

19

in the building trades, and he had not been able to do an

effective job in those courses (R. 175).

Demand for Courses.

Defendants put great reliance upon the defense for

courses that had been provided for Negroes on the basis

of need and demand.

In Interrogatory 15 (R. 375-376) Dr. Ramsey, Superin

tendent of Schools at Fort Smith admits that there is no

printing shop at the Lincoln High School and said:

“ Courses of study at Lincoln High School have been

adapted to the opportunities open to Negro students in

the community after they leave Lincoln High School” (R.

376). In open court when asked if the needs of Negro and

white students in his system were the same, Dr. Ramsey

said that in his opinion they were different because oc

cupational opportunities in the community favored the

white student (R. 383). He further testified that for the

27 years that he had been superintendent he had planned

courses for Negro and white on the basis of what he con

sidered their respeective needs (R. 384), and he admitted

that he had not followed the legislative mandate of Sep

arate but equal provisions (R. 384).

Plaintiffs contend that the rights of Negroes to enjoy

all of the privileges and advantages for public education

that are provided by the state for members of other races

is a civil right, which the Courts will protect.

Gaines v. Canada, 59 S. Ct. 232.

Westminster School Dist. v. Mendz, 161 F, 2d 993.

A civil right is a personal right, and cannot be made

to depend upon the concurrence of any third person or

persons.

McCabe v. A., T. & S. F. Railroad Co., 235 U. S.

151.

Mitchell v. U. S., 63 S. Ct. 873.

20

The defendants argued that facilities had not been

improved for Negroes due largely to lack of funds and

materials.

Plaintiffs contend that lack of funds is no defense

against proof of failure to provide equal facilities to the

members of the two races in segregated schools. In Ash

ley v. School Board, of Gloucester County, Virginia, 82 F.

Supp. 167, at 171, Judge Hutcheson, speaking for the Court

said:

I am aware of the familiar contentions that finan

cial difficulties facing the counties in the efforts to

equalize facilities and opportunities for the races are

so great as to raise doubt as to their ability to do so;

and that the greater portion of the tax burden falls

upon the white population. While I am not unmind

ful of the practical problem presented, a superficial

consideration of these suggestions is sufficient to

bring a realization that under the prevailing law

neither has any bearing upon the legal and factual

questions here involved.

Future Plans.

Throughout the trial of this cause, defendants made

no effort to show existing equality of facilities. Rather

they based their strongest defense upon future plans,

which when put into execution would make the facilities,

courses and opportunities equal for Negroes and whites.

The Court accepted and approved this line of defense.

The Court found as a fact that; The buildings and other

physical facilities at the Lincoln High School, upon the

completion of the buildings and new installations now

almost ready for occupancy and use, will be superior to the

buildings and appurtenant physical facilities at the Junior

High School and will be on substantial equality with the

combined Junior and Senior High School Buildings and

21

appurtenant physical facilities (Finding of Fact No. 19, at

R. 429).

This attitude in the Court is further seen from the

record (R. 150-151), where Mr. Greene, the principal of

Lincoln High School for Negroes, was asked to give his

opinion of the relative equality of the Negro and white

schools when the program of improvements is completed.

Counsel for Plaintiffs objected and urged that the relative

equality must be considered at the time the cause of ac

tion arose and at the time that the matter was tried.

The Court over-ruled the objection and said his deci

sion would depend largely upon what the board is doing

now, that is, whether or not they have a realization of

their responsibilities. “ I want to see whether or not they

are arbitrarily refusing” (to provide equal facilities), he

said (R. 151).

Plaintiffs contend that both the finding of fact and

the ruling were erroneous.

Where facilities have been provided for the white race

to secure public education and such facilities have not been

provided for Negroes, Mr. Chief Justice Hughes said:

* * * “ a mere declaration of purpose, still unfulfilled,

is not enough.”

Gaines v. Canada, 59 S. Ct. 232, at 235, 305 U. S.

339.

The United States Supreme Court has further held that

where separate facilities are provided for white and Negro

races they must be provided at the same time.

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of Okla., 332 U. S. 631.

Here the record clearly reveals that at the time of

trial the Howard Elementary School for Negroes upon

which defendants put so much reliance was under con

22

struction, was not complete and had no furniture in it.

Dr. Ramsey admitted that considering a school as a com

bination of buildings and facilities, library, students and

teachers the Howard School was not a school on the date

of trial (R. 357). He further admitted that the Lincoln

High School which has only eight class rooms was under

improvements and that three of the class rooms, the Library

and the Principal’s office in which certain classes are held

were under repairs and could not be used (R. 357-358).

He further admitted that the old shop at Lincoln had

been converted into a domestic science building, leaving

no shop, and that the new shop building was under con

struction, that it had no equipment in it and as such the

school had no efficient shop. Dr. Ramsey testified that

due to the disruption of the school program by the build

ing program, “ there will be some lost motion” (R. 360),

and the Negro students at the Lincoln High School had

not enjoyed the same educational opportunities and ad

vantages, during the present semester, as white children

in the district had enjoyed (R. 360), and that the loss

suffered was irreparable.

With this line of testimony in the record by the Super

intendent of Fort Smith Schools the plaintiffs contend that

the Court erred in its findings of fact as numbered in

parentheses that there was no discrimination in providing

buildings for Negroes (18), that there was no discrimina

tion in providing courses (20); that there is no dis

crimination, existing or imminent, against children of

Negro schools in the matter of courses and curriculum (21).

Dr. Ramsey admitted that he had arbitrarily provided

courses on the basis of his conception of their needs and

that the curriculum was not identical. With this before the

Court plaintiffs contend that the Court erred in its find

ing of fact that no policy, custom or usage existed to dis

23

criminate against Negro children in the School District

(23).

Facilities.

Mr. Greene, Principal of Lincoln High School admitted

that the Lincoln High School has no stadium (R. 112);

that it has no swimming pool (R. 112); that it has no music

room and no cafeteria (R. 113); that the auditorium facili

ties were not equal (R. 114); that the Lincoln High School

had no faculty lounge (R. 114); that the libraries are not

equal (R. 116); that the toilet facilities were not equal

(R. 117).

Mr. Hilliard admitted that the gymnasium facilities

at the Lincoln High School were unequal to those at the

Senior High School for white children; that he was not

qualified to teach girls; that the basket ball court was not

of standard size (R. 166); that the equipment in the

gymnasium was not standard (R. 167); that the shower and

dressing room facilities at the white and Negro schools

were not comparable (R. 168), and that there were no

tennis courts at the Lincoln High School (R. 169).

The only defense that defendants made to this was

that the teacher at Lincoln High School had failed to order

the necessary equipment (R. 170). Mr. Hilliard then tes

tified that he did not like certain equipment in his gym

nasium and counsel for defendants caused him to testify

that equipment had been provided upon the basis of what

the physical education teacher at the Lincoln High School

thought that he needed and not on any basis of equality

(R. 170).

Mr. Orr, President of the Board testified that a faculty

lounge and showers for boys and girls were under con

struction at Lincoln High School (R. 243); that there are

24

no metal lockers for students at the Lincoln High School

(R. 253); that no cafeteria facilities had been provided at

Lincoln High School (R. 254).

Dr. Ramsey admits in his answers to Plaintiffs’ In

terrogatories: that there is a Junior College for white

children (1); that Negroes may not attend the Junior Col

lege for white children (4); that no Junior College is pro

vided for Negro children (5); that there is an athletic

stadium at the white high school (8); that no stadium is

provided for Negro children at the Lincoln High School

(10); that the value of the machinery in the Printing Shop

at the white high school is approximately $30,000 (14);

that there is no printing shop at the Lincoln High School

(15); that Negro children may not study printing at the

white high school (16); that there is a cafeteria at the

white high school (20); that there is no cafeteria at the

Lincoln High School (21); that approximately 1,000 metal

lockers of the approximate value of $7,400 are provided

at the white high school (28, 29); that no metal lockers

are provided at the Lincoln High School for Negroes (30);

that the Library at the white high school is used ex

clusively by the students of that school (33); that the

library at the Lincoln High School is used in part as a

public library (35); that the auditoriums at the white

Junior and Senior high schools are used exclusively as

auditoriums (38 and 51); that the auditorium at the

Lincoln High School is a combined auditorium and gym

nasium (41); that 'there is a gymnasium in connection

with the white high school used exclusively as such (44);

that there is no swimming pool at the Lincoln High School

for Negroes (50); that the auditorium at the Junior High

School may be used by white adult groups (54); that it

may not be used by Negro students (53); that it may not

be used by Negro adult groups (55); that there is a Junior

25

High School for white children in the school district (50);

and no such Junior High School facilities are provided for

Negro children, in a separate building as is provided for

white children (56); that the white high school building

is about 20 years old (57); and that the Lincoln High

School building is about 55 years old (58) (R. 372-383).

In the light of this testimony, Plaintiffs urge that the

court erred in its findings of fact that: “ Considered as a

whole the building and other physical facilities provided

for the negro school children of the Defendant District are

not inferior to the buildings and other physical facilities

provided for the white children of the District (18), and

that the Court erred in its Conclusions of Law that: “The

Plaintiffs have failed to sustain the allegations of their

complaint” (5) and (6). A decree should be entered dis

missing the complaint for want of equity.

IV.

The plaintiffs and those similarly situated on whose

behalf they sued have been discriminated against in the

per capita expenditures made in capital invested in lands,

buildings, and equipment for educational purposes, and in

operating expenses of public schools in the district.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 70 (R. 224-225) shows the value of

land, buildings and equipment devoted to the education of

Negroes in the District for the years 1932-33, 1943-44 and

1947-48 and the number of Negro children enrolled in the

Lincoln High School for Negroes at Fort Smith, and value

of land, buildings and equipment devoted to the education

of white children in the District together with the number

of white children enrolled in grades 7 to 12 in such schools

in the District. The enrollment in the white and colored

schools represent the same grade groups, that is grades

7 to 12 in both instances. The results show:

26

Average Value of Lands, Buildings

and Equipment per Pupil

1932-33

1943-44

1947-48

Negro

$271.41

279.49

229.20

White

$406.15

500.26

457.76

Testimony with respect to these values is developed at

page 215 through page 225 of the Record.

Defendants have undertaken to rebut this testimony

by showing a different relationship in the figures, but

by their own charts, discriminations in per capita expendi

tures for lands, buildings and grounds are shown.

Defendants’ Exhibit No. 3 (R. 317) shows that in 1949

the Average Daily Attendance in the white Schools was

89.6% of the whole and that of Negroes was 10.4%. De

fendants’ Exhibit No. 6 (R. 321-322) shows that 94.3% of

the capital investment was made on 89.6% of the total

A. D. A. which represents white children, while only

5.7% of the capital investment was applied to Negroes

who represented 10.4% of the A. D. A. of the District.

That was in 1949, which is the time of trial.

When Defendants’ Exhibit No. 6 was introduced, coun

sel for plaintiffs objected to the introduction of so much of

the exhibit as had to do with future plans (R. 321), but

this objection was over-ruled by the Court (R. 322), which

ruling the plaintiffs contend was error.

It is further to be observed that the calculations made

by plaintiffs in their calculation of average per capita in

vestment in lands, buildings and equipment was based upon

the enrollment, while defendants’ calculations were based

upon Average Daily Attendance.

27

Defendants’ Exhibit No. 7 Data on Fort Smith School

Buildings shows the sanitation facilities to be “modern.”

Dr. Thomas Foltz, a physician and member of the Fort

Smith Board of Education testified that as such he had in

spected the Lincoln High School; that the Lincoln High

School was “ inadequate” from the standpoint of health

and safety and sanitation (R. 268).

Under the heading Cafeteria Service, on Defendants’

Exhibit 7, Lincoln High School is referred to as having

“ Partial” service. On cross examination on this point, Dr.

Ramsey testified that the meaning of “partial” cafeteria

service was that some of the students at Lincoln were per

mitted to go to the Old Howard School (a distance of ap

proximately five city blocks) to have meals in the How

ard Cafeteria (R. 365), which served milk only.

The Howard school referred to on the chart, Defend

ants’ Exhibit 7 is referred to as “New.” It is to be noted

that at that time the New Howard School was not com

pleted, it had no cafeteria, no students, no health service,

no attendance service and no supervisory service, Mr. Ram

sey said on the stand:

q * * * you do not deny that the Howard School at

this time is not a school in any practical sense in that

it is not the combination of buildings and facilities,

library, student and teacher, in that sense it is not a

real school today, is it?

A. That is right (R. 357).

Of sixteen white schools listed on Defendants’ Exhibit

7 only one serves milk only, all of the rest have cafeterias.

Of four colored schools listed, Lincoln, Howard (the old

school), Washington and Dunbar, not one has a cafeteria

completely equipped for cooking and serving food.

28

Per Capita Costs for Operations.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 69 (R. 219) shows an analysis of

Operating Expense for white and Negro schools, grades 7

to 12 inclusive. This chart reveals actual per capita ex

penditures for operations as reported in the Superintend

ent’s Annual Reports for the years indicated:

Actual Per Capita Difference

Expenditures for

Year Page of Report Operations

White : Negro

1932-33 57 $54.59 $36.70 $17.89

1942-43 43 72.91 44.85 28.06

1943-44 35 92.01 73.42 18.59

1944-45 34 86.31 71.01 15.30

1945-46 29 104.35 84.18 20.17

1946-47 32 116.84 107.32 9.52

1947-48 31 127.52 103.91 23.61

This chart shows a pattern of discrimination in this

respect. On the witness stand Dr. Ramsey admitted that

he knew “ in a general way” of this discrepancy in expendi

tures; that he could have known conclusively if he had

made an effort to find out (R. 216), and that it does make

a pattern of spending less on Negroes than on whites in op

erations (R. 217).

This chart was admitted over Defendants’ objection.

The Court ruled that it would be assumed to be correct;

that Defendants had the right to check and rebut its ac

curacy (R. 218). Defendants have never directly disputed

these facts.

Defendants introduced an analysis, Defendants’ Ex

hibit No. 4 (R. 319), which is the Per capita cost for instruc

tion, as against all operating expense. But this chart

29

shows the same pattern of discrimination. Defendants’

Exhibit No. 4 shows:

High Schools

Year White Colored Difference*

1945-46 $104.35 $ 84.18 20.17

1946-47 116.84 107.32 9.52

1947-48 127.52 103.91 23.61

1948-49 134.89 124.88 10.01

Dr. Ramsey admits that even his own calculations show

this pattern (R. 366). Note that for 1945-46, 1946-47 and

1947-48 our differences are the same.

Considering this testimony and evidence, Plaintiffs re

spectfully submit that the Court erred in its Finding of

Fact to the effect that there is not in existence or imminent

any policy, custom or usage in the Special School District

of Fort Smith, Arkansas, under which the Negro school

children of the District are discriminated against in favor

of the white children of the District (23).

The appellants submit that, based upon the forego

ing authorities, the decision of the trial Court dismissing

Plaintiffs’ Complaint on its own motion should be re

versed, and an order entered granting Plaintiffs the re

lief prayed for in their original and amended complaint.

Respectfully submitted,

J. R obert B o o k er ,

Century Building,

Little Rock, Arkansas,

U. S im p s o n T a t e ,

1718 Jackson Street,

Dallas, Texas,

Attorneys for Appellants.

The calculation of the difference is ours.