Correspondence from Winner to Dupree

Correspondence

May 11, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. Correspondence from Winner to Dupree, 1982. e727e14a-da92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/48e3f38d-e731-4e50-a946-d76509218b1d/correspondence-from-winner-to-dupree. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

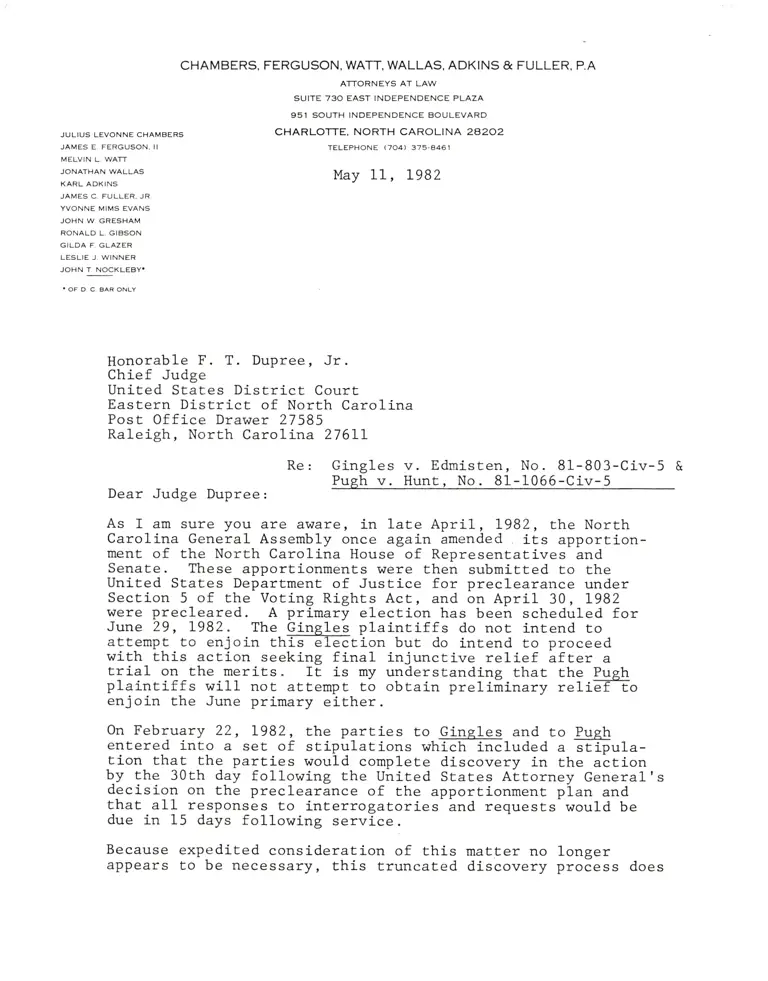

CHAMBERS, FERGUSON, WATT, WALLAS, ADKINS & FULLER, P.A

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

SUITE 73O EAST INDEPENDENCE PLAZA

951 SOUTH INOEPENOENCE BOULEVARO

CHARLOTTE. NORTH CAROLINA 28202

TELEPHONE 1704t 375-8461

May 11, L982

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERs

JAMES E, FERGUSON, II

MELVIN L, WATT

JONATHAN WALLAS

KARL ADKINS

JAMES C, FULLER. JR.

YVONNE MIMS EVANS

JOHN W. GRESHAM

RONALO L. GIBSON

GILOA F, GLAZER

LESLIE J, WINNER

JOHN T, NOCKLEBY'

. OF D C BAR ONLY

Honorable F. T. Dupree, Jr.

Chief Judge

United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

Post Office Drawer 27585

Raleigh, North Carolina 276LL

Re: Gingles v. Edmisten, No. 81-803-Civ-5

Pugh v. Hunt, No. 81-1066-Civ-5

Dear Judge Dupree:

As I am sure you are aware, in late April, L982, the North

Carolina General Assembly once again amended its apportion-

ment of the North Carolina House of Representatives and

Senate. These apportionments were then submitted to the

Unj-ted States Department of Justice for preclearance under

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, and on April 30, L982

rrere precleared. A primary eLection has been scheduled for

June 29, L982. The Gingles plaintiffs do not intend to

attempt to enjoin this election but do intend to proceed

with this action seeking final injunctive relief after a

trial on the merits. It is my understanding that the Pugh

plaintiffs will not atLempt to obtain preliminary relief to

enjoin the June primary either.

On Febr:uary 22, L982, the parties to Ginglgs and to Pueh

entered into a set of stipulations which irrcluded a Effiula-

tion that the parties would complete discovery in the attion

!y the 30th day following the United States Attorney General-'s

decision on the preclearance of the apportionment pian and

that arl responses to interrogatories ind requests would be

due in 15 days following service.

Because expedited consideration of this matter no longer

appears to be necessary, this truncated discovery process does

Honorable F. T. Dupree, Jr.

May 11, 1982

Page 2

lot appeer to be appropriate at this time. r have spoken with

James trIallace,, attorney for the defendants and Robert Hunter,attorney for the Pugh plaintiffs, and they join me in this re-quest that the paiEiEs either be allowed to-enter into a newdiscovery stipulation or that the court schedule an initialpretrial conference in order to establish a discovery schedule.

A11 parties are _cgrrently proceeding with discovery,-and we alr

]Bree thqt we will be able to concui on a new distovery stipu-lation if the court so permits. rn addition, Mr. wallale r"l

gyggts that the stipulation be delayed unril after rhe June zg,

L982 primary is he1d.

On behalf of all counsel, I thank you for your continued patience

and cooperation.

LJW: ddb

cc: Mr.

Mr.

Mr.

Mr.

Mr.

Mr.

Sincerely,

'4*l*M|'Le*1i6 J. Winner

Arthur J. Donaldson

Robert N. Hunter, Jr.

Jerris Leonard

Napoleon Williams

J. Rich Leonard w/three copies