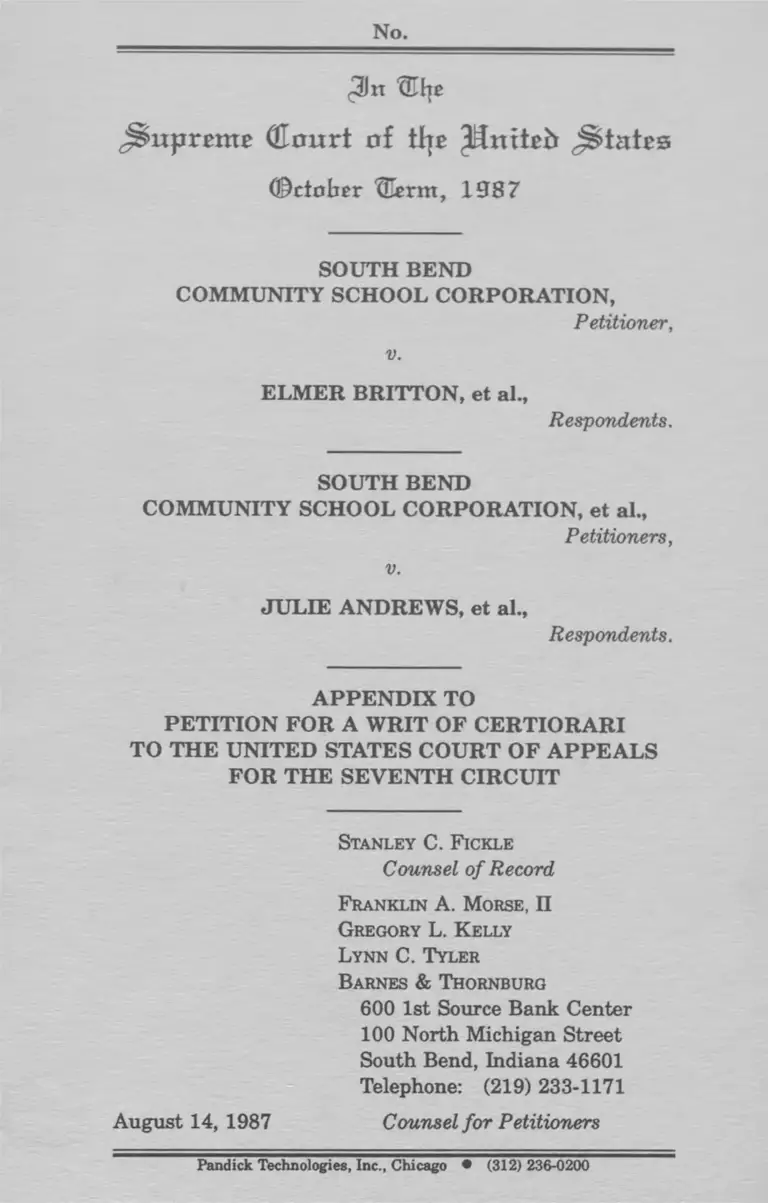

South Bend Community School Corp v Andrews Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

August 14, 1987

127 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. South Bend Community School Corp v Andrews Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1987. 757a36e0-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4963e21f-9684-4775-a5a1-61090b19afa3/south-bend-community-school-corp-v-andrews-appendix-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No.

<31n tEije

Supreme Court of tljr ^utteh J^tatrs

(October Cerm, 1987

SOUTH BEND

COMMUNITY SCHOOL CORPORATION,

Petitioner,

v.

ELM ER BRITTON, et al.,

Respondents.

SOUTH BEND

COMMUNITY SCHOOL CORPORATION, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

JULIE ANDREW S, et al.,

Respondents.

A PPEN D IX TO

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF C ERTIO RARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF A PPE A LS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

Stanley C. Fickle

Counsel o f Record

Franklin A. Morse, II

Gregory L. K elly

Lynn C. Tyler

Barnes & Thornburg

600 1st Source Bank Center

100 North Michigan Street

South Bend, Indiana 46601

Telephone: (219) 233-1171

August 14, 1987 Counsel for Petitioners

Pandick Technologies, Inc., Chicago • (312) 236-0200

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions......................... la

Judgment of Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals en banc

dated May 18, 1987 ........................................................... 2a

Opinion of Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals en banc

dated May 18, 1987 ........................................................... 4a

Order of Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals dated

February 12, 1986 ...............................................................43a

Order of Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals dated

October 21, 1985 ................................................................. 45a

Opinion of Panel of Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals

dated October 21, 1985....................................................... 46a

District Court Judgment dated September 26, 1984 . . 98a

Opinion of District Court dated September 25, 1984. . 99a

Resolution 1020 of the South Bend Community School

Corporation......................................................................... 118a

Consent Decree in United States v. South Bend

Community School Corporation dated February 8,

1980....................................................................................... 121a

Article XXIII of the 1980-83 Collective Bargaining

Agreement between the NEA-South Bend and the

South Bend Community School Corporation.................126a

la

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

U.S. Const, amend. XIV, sec. 1:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the

United States and of the State wherein they reside. No

State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United

States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection

of the laws.

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a):

(a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer —

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any in

dividual, or otherwise to discriminate against

any individual with respect to his compensation,

terms, conditions, or privileges of employment,

because of such individual’s race, color, religion,

sex, or national origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify its employees or

applicants for employment in any way which

would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of

employment opportunities or otherwise adversely

affect his status as an employee, because of such

individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin.

2a

JUDGMENT - ORAL ARGUMENT

No. 84-2841

ffiniteb JStaibs (Havtrt nf ^Appeals

cilfor ^£&entt| Qltrcmi

CUtftcago, (SlUtnots 60604

May 18, 1987.

Before

Hon. W illiam J. Bauer, Chief Judge

Hon. W alter J. Cummings, Circuit Judge

Hon. H arlington W ood, Jr., Circuit Judge

Hon. Richard D. Cudahy, Circuit Judge

Hon. Richard A. Posner, Circuit Judge

Hon. John L. Coffey, Circuit Judge

Hon. Joel M. Flaum, Circuit Judge

Hon. Frank H. Easterbrook, Circuit Judge

Hon. Thomas E. Fairchild, Senior Circuit Judge

ELM ER BRITTON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

SOUTH BEND COMMUNITY

SCHOOL CORPORATION, et

>

al.,

Appeal from the United

States District Court

for the Northern Dis

trict of Indiana, South

Bend Division.

Nos. 82-C-283

82-C-485

Defendants-Appellees J Allen Sharp, Judge.

This cause was heard on the record from the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Indiana.

South Bend Division, and was argued by counsel.

On consideration whereof, IT IS ORDERED AND

ADJUDGED by this Court that the judgment of the said

3a

District Court in this cause appealed from be, and the

same is hereby, REVERSED, with costs, and the case is

REMANDED, in accordance with the opinion of this Court

filed this date.

4a

la tip

United States Court of Appeals

3tor tip dftttttti? QUrnm

No. 84-2841

E lmer Britton, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

South Bend Community School Corporation,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Indiana, South Bend Division.

Nos. 82 C 283, 82 C 485-A lien Sharp, Chief Judge.

A rgued May 28, 1985—Reargued E n Banc October 23, 1986

Decided May 18, 1987

Before Bauer , Chief Judge, Cummings, W ood Jr.,

Cudahy, Posner, Coffey, F laum, and Easterbrook,

Circuit Judges, and Fairchild, Senior Circuit Judge.

Posner, Circuit Judge. In 1982 the public school sys

tem of South Bend, Indiana laid off 146 teachers. All were

white; 48 had more seniority than blacks not laid off; two

years later 20 of the 48 had not yet been recalled. In lay

ing off only whites, the school board was acting pursuant

to a provision in its collective bargaining agreement with

the teachers’ union to the effect that no blacks would be

laid off until every white was laid off. The laid-off teachers

sued the school system under section 1 of the Civil Rights

5a

Act of 1871, 42 U.S.C. § 1983, charging that the racially

preferential layoff provision violated the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and seeking rein

statement and damages. The district court, after a bench

trial, gave judgment for the board. 593 F. Supp. 1223

(N.D. Ind. 1984). The court thought the board’s adoption

of the provision a reasonable means toward the board’s

goal, which the court also thought reasonable, of raising

the percentage of black teachers in the South Bend school

system to that of black students. The board had resolved

‘ ‘to increase the percentage of minorities [meaning blacks]

in its teaching force until that percentage equals the per

centage of minorities in its student body. The Board

specifically resolved to increase the percentage of minority

pupils [sic—the judge meant ‘teachers’] because it deemed

it essential that the student population, both black and

white, have a sufficient number of minority teachers to

act as role models.” Id. at 1225. “ In cases dealing with

school corporations, it is proper to compare the percent

age of minority faculty with the percentage of minorities

in the student body rather than with the percentage of

minorities in the relevant labor pool . . . because of the

vital role teachers play as role-models for their students.

This is particularly true in the rise [sic—the judge ap

parently meant ‘case’] of minority teachers since ‘societal

discrimination has often deprived minority children of

other role models.’ ” Id. at 1230 n. 3.

The board appealed. A divided panel of this court af

firmed. 775 F.2d 794 (7th Cir. 1985). The full court then

granted rehearing en banc. Before the case could be re

argued, the Supreme Court decided a similar case in favor

of another group of white public school teachers. Wygant

v. Jackson Board o f Education, 106 S. Ct. 1842 (1986).

Like the panel in the present case, the Sixth Circuit had

upheld the dismissal of the complaint. The Supreme Court

reversed. It rejected the “ role models” rationale on which

the Sixth Circuit, like the district court in the present

case, had based its decision. The Supreme Court did not

remand for further proceedings to determine whether the

* No. 84-2841

6a

plaintiffs’ constitutional rights had been violated; it held

they had been. When the present case was reargued to

us, the question no longer was reversal or affirmance; it

was whether to reverse outright, holding that the plain

tiffs had proved a violation of their constitutional rights

and remanding only for the determination of the appropri

ate remedy; or to remand for further proceedings in which

the board would have an opportunity to establish a ra

tionale for racially discriminatory layoffs that would be

consistent with the Wygant decision.

The constitutional status of discrimination by public

bodies in favor of blacks and other members of minority

groups is contentious and unsettled; but with the Supreme

Court having spoken so recently to a set of facts so close

to those of the present case, the task for us is the inter

pretation of the Court’s decision rather than the forging

of new constitutional law. Wygant came out of the public

school system of Jackson, Michigan. In 1968, the year be

fore the Jackson board of education adopted a racially

preferential hiring plan, 4 percent of the city’s public

school teachers were black, compared to 15 percent of the

students. Wygant v. Jackson Board o f Education, 746

F.2d 1152, 1156 (6th Cir. 1984), rev’d, 106 S. Ct. 1842

(1986). Because Michigan’s civil rights commission believed

that the disparity was due to discrimination against black

teachers (see 106 S. Ct. at 1854), the board of education

agreed to give preference in hiring to blacks until the

percentage of black teachers was equal to that of black

students. By 1971, 9 percent of the teachers were black.

746 F.2d at 1156. That year it became necessary to lay

off some teachers. The board did this in the usual w a y -

reverse order of seniority. A disproportionate number of

those laid off were black, because so many blacks had

been hired recently and therefore had little seniority. The

racial situation in the Jackson public schools soon became

even more tense—became, indeed, violent. See 106 S. Ct.

at 1859. Expecting that additional layoffs would be neces

sary in the near future, the board decided it must take

measures to make sure that such layoffs would not reduce

No. 84-2841 3

7a

the number of black teachers disproportionately. The board

felt it needed to have as many black teachers as possible

in order to quiet the schools and give black students role

models. It also feared that the hiring of blacks would be

impeded by strict adherence to the principle of laying off

teachers in reverse order of seniority, because new teachers

would know they would be the first to be laid off if there

was a reduction in force.

In 1972 the board negotiated with the teachers’ union an

agreement (which became Article XII of the collective bar

gaining contract with the union) to deviate from the prin

ciple of laying off teachers in reverse order of seniority,

but only to the extent necessary to preserve the existing

percentage of blacks (and other members of minority groups,

but we can ignore that feature of the case) in the teaching

force. So if 10 percent of the teachers were black, no more

than 10 percent of the teachers laid off could be black.

The collective bargaining contract in Wygant was rati

fied by an overwhelming majority of the Jackson public

school teachers, most of whom were white. Nevertheless,

in a suit by white teachers laid off because of Article XII,

the Supreme Court held that the provision was a denial

of equal protection. Although there was no majority opin

ion in Wygant, a “ lowest common denominator” majori

ty position can be pieced together. “When a fragmented

Court decides a case and no single rationale explaining

the result enjoys the assent of five Justices, ‘the holding

of the Court may be viewed as that position taken by

those Members who concurred in the judgments on the

narrowest grounds.’ ” Marks v. United States, 430 U.S.

188, 193 (1977).

Justice Powell, writing in Wygant for three Justices,

opined that a public body may not use race as a criterion

for layoffs unless necessary to protect a proven victim of

discrimination, such as a black who if he had not been

discriminated against would have had as much seniority

as a white. See 106 S. Ct. at 1849-52. Justice White took

the same position, only more bluntly. See id. at 1857-58.

4 No. 84-2841

8a

Obviously if either of those opinions had commanded a

majority, we would have to reverse outright. But since

Justice O’Connor, the fifth and last member of the ma

jority, concurred in the judgment of reversal on the nar

rowest ground, her opinion is critical to our determining

the proper disposition of the present case.

She reserved the question whether a racially preferential

layoff plan might ever be a constitutionally permissible

measure “ to correct apparent prior employment discrimi

nation against minorities while avoiding further litigation,”

id. at 1854 (see also id. at 1857), and she noted in this

connection that the Jackson school board had “ reasoned

that without the layoff provision, the remedial gains made

under the ongoing hiring goals contained in the collective

bargaining agreement could be eviscerated by layoffs,”

id. at 1854. The fact that there had been no authoritative

determination of hiring discrimination and that the layoff

provision would not merely benefit victims of such discrim

ination did not in her view automatically condemn the

plan. Nevertheless she agreed that the plan was uncon

stitutional and that outright reversal was the proper dis

position of the appeal, because the plaintiffs had

met their burden of establishing that this layoff provi

sion is not “ narrowly tailored” to achieve its asserted

remedial purpose by demonstrating that the provision

is keyed to a hiring goal that itself has no relation

to the remedying of employment discrimination.

Id. at 1857. That is,

the hiring goal that the layoff provision was designed

to safeguard was tied to the percentage of minority

students in the school district, not to the percentage

of qualified minority teachers within the relevant

labor pool. The disparity between the percentage of

minorities on the teaching staff and the percentage

of minorities in the student body is not probative of

employment discrimination. . . . Because the layoff

provision here acts to maintain levels of minority hir

ing that have no relation to remedying employment

No. 84-2841 5

9a

discrimination, it cannot be adjudged “ narrowly tai

lored” to effectuate its asserted remedial purpose.

Id. (citation omitted). The hiring goal in the present case

was likewise “ tied to the percentage of minority students

in the school district.”

Justice Marshall, the author of the principal dissenting

opinion in Wygant (which Justices Brennan and Blackmun

joined), made two points that are particularly relevant to

the present case. First, he noted that an alternative to a

racially proportional layoff provision—such as Article XII,

which merely preserved the percentage of black teachers

achieved before the layoffs—“ would have been a freeze

on layoffs of minority teachers. This measure . . . would

have been substantially more burdensome than Article XII,

not only by necessitating the layoff of a greater number

of white teachers, but also by erecting an absolute distinc

tion between the races, one to be benefited and one to

be burdened, in a way that Article XII avoids.” Id. at

1865. That hypothetical “ substantially more burdensome”

measure is the one the South Bend school board adopted.

Second, Justice Marshall took exception to the majority’s

refusal to remand the case for findings on possible justi

fications for Article XII other than those the majority had

rejected. The district court had granted summary judg

ment for the Jackson board of education because the court

found, on the basis of evidence that a much higher per

centage of students than of faculty was black, that favor

ing blacks in layoffs was necessary both to give black

students adequate “ role models” and to rectify “ societal

discrimination” against black teachers (“ societal discrimi

nation” meaning a racial imbalance not caused by the

defendants’ own discriminatory acts). The defendants in

Wygant, perhaps foreseeing rejection of these grounds,

submitted evidence relevant to other possible justifications

to the Supreme Court. The submission had no standing

as evidence, but it provided a reason for remanding the

case to give the lower courts a chance to consider it. The

rejection of Justice Marshall’s suggestion that the case

6 No. 84-2841

10a

be remanded has implications for the present case, which

the defendants have asked us to remand.

South Bend, Indiana, like Jackson, Michigan, had a lower

percentage of black teachers in its public schools than of

black students. In 1978, on the eve of adopting a racially

preferential hiring plan, the percentages were 10 and 22.

Although the 10 percent figure is more than twice the

percentage of black teachers in the Jackson public schools

at the corresponding period in the evolution of its program

of racial preferences, the South Bend school board was

not satisfied, and resolved to raise the percentage of black

teachers until it equaled that of black students. The layoff

plan ensured that if layoffs were necessary they would

not impede achievement of the board’s goal of racial parity

between teachers and students. Indeed, since no blacks

could be laid off if any whites had not yet been laid off,

the layoff plan (unlike the one in Wygant) was calculated

to increase rather than just maintain the percentage of

black teachers in the event that any layoffs became neces

sary. By 1981, 13 percent of the teachers (and 25 per

cent of the students) were black. As a result of the layoff

provision, the percentage of black teachers rose—to 14

percent—when it became necessary to lay off teachers,

since all of those laid off were white.

No one doubts that the signatories of the plurality opin

ion in Wygant, plus Justice White (a total of four Justices),

would invalidate South Bend’s racially preferential layoff

plan. The plan goes further than the one struck down in

Wygant, unlike Wygant there is no background of racial

violence; as in Wygant there is no evidence that any of

the black teachers who have benefited from the plan are

victims of racial discrimination that deprived them of

seniority they would otherwise have had. Conceivably

Justice O’Connor might approve a racially preferential lay

off plan of some sort (a critical qualification, as we shall

see) if she were convinced that the purpose of the plan

was to correct previous hiring discrimination by the school

board. There was some evidence in the record before the

Supreme Court in Wygant that that had been the Jackson

No. 84-2841 7

11a

school board’s purpose; there is very little evidence that

it was the South Bend board’s purpose. The goal advanced

by the board in the district court—the goal to which all

of the board’s evidence was oriented—was to correct a

discrepancy between the percentage of black teachers and

the percentage of black students. Such a discrepancy is,

in Justice O’Connor’s view, “ not probative of employment

discrimination,” 106 S. Ct. at 1857 (emphasis added), and

therefore cannot, in her view, justify racially discrimina

tory layoffs. For her the proper comparison in deciding

whether black teachers have been discriminated against

is not between the percentage of black teachers and the

percentage of black students but between the percentage

of qualified black teaching applicants who are hired and

the percentage of qualified white applicants who are hired;

if 10 percent of the qualified blacks are hired but 20 per

cent of the qualified whites are hired, this would be evi

dence of racial discrimination in hiring. See id.; J. Edinger

& Son, Inc. v. City o f Louisville, 802 F.2d 213, 216 (6th

Cir. 1986). Nowhere in the transcript of the trial or in

the trial exhibits do we find evidence that the purpose

of the South Bend school board in seeking to equate the

fraction of black teachers to the fraction of black students

was to remedy employment discrimination. The district court

did not overlook this theory of the defense; the theory simply

was not presented to the court. Cf. 593 F. Supp. at 1231.

The board put all its forensic eggs in the baskets labeled

“ role models” and “ racial imbalance.” The board’s counsel

said at trial, “ statistical disparity, that’s all that’s neces

sary . . . . So our evidence, Your Honor, in terms of justify

ing this provision, is going to be that of showing the sta

tistical disparage [sic] between the proportion of Blacks

in the teaching force of the corporation, and the propor

tion of [black] students in the student body.”

The record contains some evidence bearing on discrimi

nation against blacks, but because discrimination was not

the focus of the district court proceedings, the evidence

is sparse, and it is also ambivalent. Far from discriminat

ing against black teachers, the South Bend school board

8 No. 84-2841

12a

had for years been hiring a much higher fraction of black

than of white teaching applicants. As early as 1972—eight

years before the collective bargaining provision challenged

in this case—22 percent of all the new hires were black.

In 1974 this figure was 30 percent; in 1980, 55 percent.

Granted, this is not the complete picture. In 1975, five years

before the layoff provision at issue in this case was adopted,

HEW wrote a letter to the school board alleging racial

discrimination in the South Bend public school system.

However, the only concern expressed in the letter with re

spect to discrimination in hiring involved the discrepancy

between the fraction of black students and the fraction

of black teachers—the theory of discrimination discredited

by Wygant. And the school board’s reply to the letter de

tailed the board’s vigorous efforts to recruit black teachers,

efforts that included not only soliciting teaching applica

tions from black colleges but also hiring a much higher

fraction of black than of white applicants. A second let

ter that HEW wrote in 1975 is silent on discrimination

in hiring, and a third is a form letter apparently written

to all public school superintendents in the country. The

record also contains an unsworn, unsubstantiated, unelabo

rated charge by a member of the audience at a public

meeting unrelated to this case, that the board had un

justly refused to hire five (unnamed) black teaching ap

plicants. Even if this accusation were accepted as true,

it would imply—in the context of uncontradicted evidence

that blacks were favored in hiring, consistently with the

board’s goal of raising the percentage of black teachers

to the percentage of black students—a mistaken person

nel decision rather than an act of deliberate discrimina

tion. Finally, Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215,

1221 (D.C. Cir. 1976), noted that HEW had years ago ac

cused the South Bend board of some unspecified form of

racial discrimination, but the opinion does not suggest that

the accusation is true, or concerned discrimination in hir

ing. And HEW never did bring suit.

South Bend may have engaged in a different form of

discrimination—assigning black teachers to teach black

No. 84-2841 9

13a

students—for which the proper remedy would be to en

join this practice, as a consent order did in 1980. The

order said nothing about giving blacks superseniority, for

that \vould not be a logical remedy for discrimination in

assigning teachers. That Indiana had a segregated school

system almost 40 years ago is another fact that pertains

to discrimination in assigning, not in hiring, teachers.

Steering black teachers to black schools could actually lead

to hiring more black teachers than if there were no steer

ing, by earmarking all teaching slots in black schools for

blacks. Granted, in 1964 only 4 percent of the teachers

in the South Bend public school system were black, yet

there is no evidence that this was due to discrimination

in hiring or assigning; the percentage of blacks in South

Bend wras also lower then.

Given the long history of discrimination against black

people, in Indiana as elsewhere, we cannot exclude the

possibility that the South Bend school board, perhaps until

fairly recently, discriminated against black teachers in hir

ing and that the layoff provision challenged in this case

was adopted, in part at least, to correct that discrimina

tion by protecting newly hired black teachers against be

ing laid off in the event of an economic downturn. One

would think, however, that if this were so, the board

would have argued the point in the district court; for

while Wygant, decided later, withdrew certain justifica

tions for such provisions, it did not create a new one (cor

recting previous discrimination). The board had every in

centive to assert all its possible defenses in the district

court; any not asserted would ordinarily be deemed waived.

See, e.g., National Fidelity Life Ins. Co. v. Karaganis,

811 F.2d 357, 360-61 (7th Cir. 1987); Benzies v. Illinois

Dept, o f Mental Health & Developmental Disabilities, 810

F.2d 146, 149 (7th Cir. 1987). The Supreme Court did not

remand Wygant, as Justice Marshall had suggested it do,

to permit the Jackson board of education to prove that

its layoff provision had been designed to rectify previous

discrimination in hiring—of which the board had in fact

been accused.

10 No. 84-2841

14a

Despite all this it might be arguable as an original mat

ter that the evidence of remedial purpose, although weak,

is stronger than in Wygant and that the South Bend

school board should have a chance to shore up that evi

dence on remand—were it not for Justice O’Connor’s in

sistence that even a remedial layoff plan be “ narrowly

tailored,” a requirement that the plan in this case flunks

even more decisively than the plan in Wygant Recall that

Justice O’Connor was willing to accept the possibility that

the layoff plan had been adopted in order to correct the

Jackson school board’s “ apparent prior discrimination.”

But that wasn’t good enough; the plan was invalid be

cause tied to an improper hiring goal, that of equating

the fraction of black teachers to the fraction of black stu

dents. The plan in the present case is tied to the same

goal, and really no more need be said to condemn the

plan. But there is more: enough more, indeed, that even

Justice Marshall and the two Justices who joined him

might think South Bend had gone too far, by erecting an

absolute racial preference for blacks. That goes further

than necessary to preserve blacks’ gains in times of eco

nomic downturn, and further than the proportional prefer

ence struck down in Wygant.

Between 1979 and 1981 the South Bend school board

hired 62 blacks, and it was the 48 most recently hired of

these blacks, 41 of whom had been hired since 1980, who

would have been laid off under a racially neutral layoff

plan. Thus, no matter how recently hired a black was,

he was placed on the seniority ladder above every white

teacher. In addition to giving every black an absolute

preference over every white, the plan ties the percentage

of black teachers to such irrelevant and unpredictable cir

cumstances as the economic health and school-age popula

tion of South Bend; the plan uses economic downturns and

shrinkages in the student population as fulcrums for arbi

trarily increasing the percentage of black teachers in the

public school system. A plan with such effects cannot be

held to be “ narrowly tailored” to the goal of remedying

previous discrimination, even if that was the board’s goal,

No. 84-2841 11

15a

of which there is, as we have said, almost no evidence

in the record, and even if such a goal could save a layoff

plan tied to a hiring goal of equating the percentage of

black teachers to the percentage of black students, which

Justice O’Connor (and a fortiori the other four Justices

in the majority in Wygant) believed it could not.

The school board has argued (though not until reargument

en banc was granted) that it didn’t really lay off these

whites, because it offered them substitute positions, though

at reduced compensation. But the board’s counsel acknowl

edged at argument that his client would have violated the

equal protection clause if it had tried to solve its finan

cial problems by cutting just white teachers’ wages or

fringe benefits (estimated to be worth between $2,000 and

$4,000 a year), without laying off anybody. Yet that is

what he says the board actually did, by offering to hire

the laid-off whites as substitute teachers at a reduced

level of compensation.

The judgment of the district court is reversed, and the

case is remanded for further proceedings consistent with

this opinion.

12 No. 84-2841

F laum, Circuit Judge, joined by Bauer, Chief Judge,

concurring in the judgment and concurring in part.

I.

I join with Judge Posner in concluding that the plan

adopted by the South Bend School Board was not narrow

ly tailored because it created an absolute preference for

black teachers and thereby imposed a burden on white

teachers that was greater than necessary to achieve even

the most compelling purpose. I therefore agree that, in

light of Wygant, the Board’s plan fails the test of strict

scrutiny and must be held unconstitutional. However, I

write separately to express my understanding of the stand

ards that govern our consideration of the constitutionality

16a

of affirmative action plans adopted by public employers. I

also write separately to offer guidance to the district court,

which on remand must determine the relief to which each

plaintiff is entitled.

In light of Wygant, it is clear that a court may only

uphold an affirmative action plan that is adopted by a

public employer, and challenged under the Equal Protec

tion Clause, if the court first determines that the em

ployer adopted the plan to achieve a “ compelling pur

pose.” Remedying its own past discrimination is indis

putably one such purpose.1 This does not mean, however,

that a court may only uphold an affirmative action plan

intended to remedy past discrimination if it determines

that the public employer actually discriminated. Rather,

the critical inquiry is whether the employer, giving due

consideration to the rights of all employees, had “ a firm

basis for determining that affirmative action [was] war

ranted,” Wygant, 106 S.Ct. at 1856 (O’Connor, J., con

curring in part), and whether it acted based on that belief.

In resolving this issue, a court may consider both direct

and circumstantial evidence.

At trial, the South Bend School Board, relying on the

Sixth Circuit’s opinion in Wygant, stressed the “ role

model” theory. As a result, the record on appeal is neces

sarily incomplete as to the Board’s reason for adopting

the plan. Nonetheless, the record indicates that the Board

maintained a dual school system; received letters from

government agencies suggesting that it had discriminated;

heard statements made at public meetings accusing it of

discrimination; and signed a consent decree barring racial 1

No. 84-2841 13

1 Remedying past discrimination is not necessarily the only gov

ernment purpose sufficiently compelling to justify the remedial use

of race. Providing faculty diversity may be a second. Wygant, 106

S.Ct. at 1853 (O’Connor, J., concurring in part). There may be

“other governmental interests . . . [that are] sufficiently ‘important’

or ‘compelling’ to sustain the use of affirmative action policies.” Id.

17a

“ steering” of teachers. Although these facts do not con

clusively establish that the Board discriminated against

black teachers in hiring, they are sufficient to permit a

court to conclude that the Board reasonably believed that

it had discriminated. The record also indicates that, al

though the School Board stressed the role model theory,

it did suggest at trial that it had adopted the layoff plan

to remedy its past discrimination. See, e.g., Trial Tran

script 91-92, 95-96 (testimony of former board member

H. Hughes).

Although the Board appears to have had a compelling

purpose, its plan must fail because it was not narrowly

tailored. If the Board had sought to remedy its past dis

crimination by maintaining the percentage of black teachers,

it could have adopted a proportional layoff plan. Such a

plan might have been constitutionally permissible in this

case. See Firefighters Local Union No. 178k v. Stotts, 467

U.S. 561, 583 (1984) (leaving open the question of whether

a public employer may voluntarily adopt a proportional

layoff plan); see also Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Company, 424 U.S. 747, 778-79 (1976) (A collective bar

gaining agreement may “ enhancfe] the seniority status of

certain employees . . . to the end of ameliorating the ef

fects of past racial discrimination.” ). If the Board had

reasonably believed that the only means to remedy its

past discrimination was by continuing to increase the

percentage of black teachers, it could conceivably have

been permissible for it to adopt a disproportional layoff

plan. Cf. United States v. Paradise, 107 S.Ct. 1053 (1987)

(disproportional hiring plan permissible to remedy extreme

discrimination by a state actor). The fatal flaw in the

Board’s plan is that it placed the entire burden on the

white teachers. II.

14 No. 84-2841

II.

On remand, the district court must make an individual

ized assessment of the compensatory and equitable relief

to which each plaintiff is entitled. The court should grant

18a

compensatory relief only for those injuries that would not

have occurred but for the Board’s unconstitutional action.

For example, those plaintiffs who would have been laid

off even if the Board had used its pre-existing seniority

system do not appear to have suffered a compensable in

jury. Moreover, any award of compensatory relief should

reflect the mitigation of damages resulting from the sub

stitute teaching and recall provisions.

In determining the equitable relief to which the plain

tiffs are entitled, I believe that the district court should

be guided by the existing case law concerning “ compen

satory seniority.” The Supreme Court has stated that the

“remedial interest of the discriminatees” must be balanced

against “ the legitimate expectations of other employees

innocent of any wrongdoing.” Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324, 371-77 (1977). In particular, the Court has

indicated that those plaintiffs who have not been recalled

are “ not automatically entitled to have [an incumbent]

employee laid off to make room” for them. Firefighters

Local Union No. 178U v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561, 579 (1984). III.

III.

The outcome in this case should not be construed as

a retreat from our belief that the eradication of racial bar

riers must remain one of the highest priorities of our

society, and our recognition that when these barriers are

the result of intentional discrimination by a state actor,

the Constitution elevates this priority to the status of an

affirmative command. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board o f Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971). Although we have

rejected the plan at issue, our result does not signal any

hesitation to uphold reasonable affirmative action pro

grams, even if “ innocent persons [are] called upon to bear

some of the burden of the remedy,” Wygant v. Jackson

Board o f Education, 106 S.Ct. 1842, 1850 (1986) (plurality).

Our efforts as a society to remedy the appalling legacy

of discrimination are far from finished.

No. 84-2841 15

19a

Cummings, Circuit Judge, with whom Judges W ood, Jr.,

Cudahy, and Fairchild join, dissenting. Vftiile fully join

ing Judge Cudahy’s dissent, I feel it is necessary to voice

my objection to the grounds relied upon by the plurality

and concurrence. “ It is now well established that govern

ment bodies, including courts, may constitutionally employ

racial classifications essential to remedy unlawful treat

ment of racial or ethnic groups subject to discrimination.”

United States v. Paradise, 107 S. Ct. 1053, 1064 (plurality

opinion); Local 28 o f the Sheet Metal Workers’ Int’l Ass’n

v. EEOC, 106 S. Ct. 3019, 3052 (plurality opinion). Also

beyond dispute is the importance of voluntary efforts on

the part of public employers, as well as private employers,

to eliminate the lingering effects of racial discrimination,

even those effects not attributable to the entity’s own

practices. Johnson v. Transportation Agency, 107 S. Ct.

1442, 1456-1457; United Steelworkers v. Webber, 443 U.S.

193, 208. This concern rises to the level of a constitutional

duty to take affirmative action when the lingering dis

criminatory effects are due to a public employer’s own

past discrimination. Wygant v. Jackson Board o f Educa

tion, 106 S. Ct. 1842, 1856 (O’Connor, J., concurring);

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 200; Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402 U.S.

1, 15; Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 437-

438. Today’s treatment of the layoff plan of the South Bend

Community School Corporation (the “ School Corporation” )

will unjustifiably discourage public employers from volun

tarily meeting their constitutional obligations to undertake

race-conscious remedial measures.

Public employers who undertake race-conscious remedial

measures must consider the need for the measures as well

as their effects on the rights of employees innocent of

discriminatory wrongdoing. Although a majority of the

Supreme Court has yet to reach agreement on the stand

ard for reviewing an equal protection challenge to a public

employer’s affirmative action program, if that plan meets

the requirements of strict scrutiny then there can be no

doubts as to its constitutionality. Paradise, 107 S. Ct. at

16 No. 84-2841

20a

1064. Because we cannot determine on the basis of the

record before us that as a matter of law plaintiffs have

met their burden of establishing that the School Corpora

tion’s layoff provision violated the Equal Protection Clause,

even giving them the benefit of the strictest standard for

reviewing such plans, this case should be remanded to the

district court for further fact-finding.

The evidence and testimony presented at trial and laid

out in Judge Cudahy’s dissenting opinion herein show that

the School Corporation had a “ firm basis” for believing

that race-conscious remedial measures were necessary. See

Wygant, 106 S. Ct. at 1856 (O’Connor, J., concurring). The

layoff provision was adopted in 1980 after more than a

decade of increasing criticism of the School Corporation’s

policies and practices that maintained a dual school sys

tem—officially prescribed by Indiana law until 1949—in

which some schools could be identified as “ white” or

“ black.” In 1967, the School Corporation was forced by

a lawsuit to abandon plans to construct a new school on

the site of a school that was 99% black and alleged to be a

product of de jure segregation. Def. Ex. M-6. There was

evidence that black teachers were assigned to predomi

nantly black schools, which received less maintenance and

substantially less financial support, and that black teachers

had little opportunity for promotion. Id. In 1975, the Of

fice for Civil Rights of the Department of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare determined that the School Corporation

was intentionally segregating faculty members. Def. Ex.

M-3. This finding alone creates a prima facie case of a

violation of the Equal Protection Clause justifying race

conscious remedies, Swann, 402 U.S. at 18, but there was

even more. In the mid-1970’s the Board of Trustees of

the School Corporation discussed the fact that racially

identifiable schools existed and that minority teachers and

students were concentrated in “ black schools.” Trial Tr.

91-92 (testimony of Hollis Hughes, Jr., former member of

the Board). In 1976, the School Corporation made only

failed attempts, and “ not very strong attempts,” to dis

mantle its dual school system. Id. at 92. In May 1978,

No. 84-2841 17

21a

the State of Indiana Office of Schoolhouse Planning for

bade construction of new facilities until the School Cor

poration addressed the problem of racially identifiable

schools. Id. at 93.

Under pressure from the State of Indiana and the federal

government, the School Corporation finally took significant

steps to dismantle its dual school system. In December

1978, it adopted an affirmative action hiring program,

Resolution 1020. In February 1980, after the federal gov

ernment had brought suit, the School Corporation entered

a consent decree to desegregate its schools by changing

its faculty and student assignment policies. Def. Ex. C-l.

That consent decree required it to continue its affirmative

action hiring programs and report to the federal govern

ment its total faculty, by race, until the end of 1983. Id.

3 at 1 8, 4 at 1 10(a). In May 1980, the School Corpora

tion entered a 3-year collective bargaining agreement that

included the no-minority layoff provision.

Therefore, the trier of fact on remand could find that

the School Corporation had a firm basis for believing it

necessary to adopt a remedy even as drastic as the 3-year

no-minority layoff provision. For race-conscious remedies,

“ the nature of the violation determines the scope of the

remedy.” Swann, 402 U.S. at 16. Here the School Cor

poration waited for more than 20 years after Brown v.

Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483, to begin to dismantle

its dual school system and in the meantime continued its

policies of maintaining racially identifiable schools until it

was forced to change. Although facially appealing, our in

quiry into the constitutionality of the layoff provision does

not end with the simple observation that the School Cor

poration’s provision barred the laying off of any black

teachers while Wygant struck down a plan merely requir

ing proportional layoffs. Unlike Wygant where there was

no evidence of intentional discrimination, see Sheet Metal

Workers, 106 S. Ct. at 3053 (plurality opinion); see also dis

senting opinion herein at pp. 27-28 (Cudahy, J.), here a trier

of fact could find that the School Corporation reasonably

believed that such immediate action was necessary to

18 No. 84-2841

22a

maintain the present number of black teachers. The pro

vision enabled the School Corporation to preserve its af

firmative action hiring gains and to counter the linger

ing discriminatory atmosphere traceable to its recently

abandoned policy of assigning black teachers to “ black

schools,” and to do all this in an expedited manner in

order to compensate for its past delays in meeting its con

stitutional obligations—to teachers and students—to “ elimi-

nate[ ] root and branch” any vestiges of past discrimina

tion. Paradise, 107 S. Ct. at 1066 n.20, 1067-1074; Green,

391 U.S. at 437-439. The temporary layoff provision was

not only a remedy for past discrimination against black

teachers, but also was part and parcel of the School Cor

poration’s constitutionally mandated efforts to replace its

dual school system with an integrated learning environ

ment.

Rather than allowing the trial court to determine if

plaintiffs have proven that the layoff provision was not

narrowly tailored to its remedial purpose, the plurality

here believes that the plan is “ invalid because tied to an

improper hiring goal.” Plurality opinion at p. 11. The hir

ing policy, Resolution 1020, which mentioned the percent

age of minority students as a goal for the percentage of

minority teachers, was a separate resolution of the Board

of Trustees, and, unlike the one in Wygant, not part of,

nor compelled by, the collective bargaining agreement. See

Wygant v. Jackson Board o f Education, 746 F.2d 1152,

1158 (6th Cir. 1984), reversed, Wygant, 106 S. Ct. 1842.

That the provision was not tied to any hiring goal is made

clear by the fact that any teachers laid off because of the

agreement would be hired back first when new openings

became available. Def. Brief on Rehearing En Banc 23.

Because any gains in the percentage of black teachers

would evaporate as soon as budgetary constraints eased,

the hiring goal would not be furthered. Also, the small

number of white teachers who but for the provision would

not have been laid off—perhaps only 13 to 16 people—and

the less than 1% increase in the fraction of black teachers

belie the suggestion that the provision was tied to the

No. 84-2841 19

23a

hiring goal. Id. at 22-24. The School Corporation believes

that it can present evidence that it considered in advance

the “ probable size of the anticipated layoff and the prob

able effects of [the layoff provision] on the laid-off teachers,”

id. at 7 n.2, which would not only establish that it was

designed to be narrowly tailored, but also show that it

was not intended to achieve the goal of equating the per

centage of black teachers to black students. Thus further

fact-finding, now made necessary by Wygant, could dispel

this first objection of my. brethren.

A second reason advanced by both the plurality and con

currence for holding that plaintiffs have proven that the

provision was not narrowly tailored as a matter of law

is that it erects an “ absolute preference” between the

races and places the “ entire burden” on white teachers.

Their opinions ignore our uncertainty over inter alia the

extent of past discrimination and its lingering effects, a

determination that defines the appropriate extent of the

remedy, see Swann, 402 U.S. at 16, by in effect espous

ing a per se rule that affirmative action programs that

can be characterized as creating an “ absolute preference

for minorities” can never be narrowly tailored.

The shortcoming of this approach is that the validity

of an affirmative action program will then depend on how

one chooses to define the benefits bestowed by that pro

gram. Any advantage bestowed on a minority by an af

firmative action program can be characterized as an “ ab

solute preference” if just that advantage is considered and

as “ not an absolute preference” if the chosen referent is

the larger objective that the advantage is intended to help

minorities obtain. Thus in United States v. Paradise, ap

parently the plurality and concurrence would invalidate

the remedy if they chose the referent as the 8 promo

tions to corporal rank set aside for blacks but would up

hold it if they chose the referent as promotion to the cor

poral rank because blacks had no absolute preference for

the remaining 8 openings. See 107 S. Ct. at 1071-1072 and

n.30, 1073 (plurality opinion). In Sheet Metal Workers, the

Supreme Court upheld the court-ordered establishment of

20 No. 84-2841

24a

a fund which provided only minority youths with part-

time and summer sheet metal jobs, counseling, tutorial

services, and financial assistance during apprenticeship,

stating that there was no absolute preference for minor

ities to be union members, as opposed to fund benefici

aries. 106 S. Ct. at 3030, 3053 (plurality opinion). Likewise,

in the present case the layoff provision does not create

an absolute preference for minorities because it did not

prevent whites from teaching in the South Bend schools—

the vast majority of those positions continued to be held

by whites—or from being hired as teachers to fill posi

tions when no qualified laid-off employee was available.

Furthermore, the provision was effective for only three

years, the School Corporation expected that few teachers

would be affected by it, and the School Corporation pro

vided substitute positions to many of those who were

affected.

It is true that Justice Marshall’s Wygant dissent em

ployed the phrase “ absolute distinction between the races”

to argue that the Wygant layoff provision was less bur

densome than a no-minority layoff provision. 106 S. Ct.

at 1865. But nowhere did he suggest that if an affirmative

action program can be characterized as creating an “ ab

solute distinction,” then it is not narrowly tailored as a

matter of law. Such a per se approach is bothersome.

Whether a plan can be characterized as creating an “ ab

solute distinction” is but one fact to consider. Given that

such a characterization is easily subject to manipulation

to produce any desired result, it is not a very probative

fact. We should instead weigh the extent of the public

employer’s interest, the precise burdens imposed on in

nocent non-minorities, and the adequacy of less onerous

alternatives. Here remand is required because, unlike

Wygant, it cannot be decided if this provision is narrow

ly tailored without first resolving factual questions which

will determine a proper appraisal of all three of these fac

tors.

In the present case the temporary no-minority layoff

provision, as drastic as it is, may be necessary to elimi

No. 84-2841 21

25a

nate the effects of the School Corporation’s past discrimi

nation and continued default of its constitutional obliga

tions. The concurrence herein is willing to assume that

a proportional layoff plan, or even a disproportional layoff

plan, may have been supportable by the School Corpora

tion’s remedial purpose. However, given the twenty-plus

years of delay in dismantling its dual school system and

the resultant discriminatory atmosphere discouraging blacks

from teaching at its schools, the School Corporation could

well have been justified in deciding that a drastic-but-

temporary remedy was needed to bring about an immedi

ate break with its segregationist past, even during times

of a fiscal crisis. The School Corporation owed no less to

its students and faculty and indeed had a burden of com

ing forward with “ a plan that promises realistically to

work, and promises realistically to work now.” Green, 391

U.S. at 439 (emphasis in original). Reducing the number

of black teachers at the very time it was attempting to

dismantle its dual school system and provide its students

with an integrated learning environment that they had

been unconstitutionally denied for twenty-plus years would

have undermined these efforts. The unconscionable delays

in eliminating the vestiges of discrimination counseled

against the School Corporation waiting for an end to its

fiscal crisis to provide that integrated learning environ

ment.

The Supreme Court has recently recognized that drastic

short-term remedies may be needed to compensate for

lengthy delays in eliminating past discrimination. In

United States v. Paradise, the Court upheld a court-

imposed 50% promotion quota for black Alabama state

troopers although the relevant labor pool was only 25%

black. 107 S. Ct. at 1068-1070, 1071-1072 (plurality opin

ion). The Court concluded that “ [i]t would have been im

proper for the District Judge to ignore the effects of the

Department’s delay and its continued default of its obliga

tion to develop a promotion procedure, and to require only

that, commencing in 1984, the Department promote one

black for every three whites promoted.” Id. at 1072. In

22 No. 84-2841

26a

stead, the 50% promotion quota “ provided an accelerated

approach to achieving [the 25%] goal to compensate for

past delay” and was consistent with its school desegrega

tion cases which have “ recognized the importance of ex

pediting elimination of the vestiges of longstanding

discrimination.” Id. at 1072 n.30 and n.31. In the present

case a trier of fact could justifiably conclude that plain

tiffs failed to prove that the layoff provision was not nar

rowly tailored to ending the School Corporation’s long

standing default of its constitutional affirmative duty to

dismantle all vestiges of discrimination. No less burden

some layoff provision might bring about the same benefits

as quickly, and the extent of the School Corporation’s past

discrimination and delays could justify the burdens im

posed; therefore, remand is necessary.

The efforts of the School Corporation to meet its con

stitutional obligation to replace its dual school system with

an integrated learning environment and to eliminate the

lingering effects of its discrimination against black teachers

cannot be lightly dismissed. Without further fact-finding

as to the extent of the School Corporation’s compelling

interest, the burdens imposed on innocent white employ

ees, and the adequacy of less onerous alternatives, this

Court cannot determine whether the School Corporation’s

layoff provision is narrowly tailored. Plaintiffs’ failure to

meet their burden of proving the invalidity of the provi

sion cannot be masked by reliance on talismanic factors

shortcutting important factual determinations and yielding

clear yet erroneous results. Therefore I respectfully dis

sent.

No. 84-2841 23

Cudahy, Circuit Judge, with whom Judges Cummings,

W ood, Jr., and Fairchild join, dissenting:

We are dealing here with a race-conscious layoff plan,

voluntarily adopted by a school board under heavy govern

ment fire for past discrimination and ratified by secret

27a

ballot by the teachers affected.1 What is most striking

about this case is the kaleidoscope of legal scenery against

which the facts have been projected at various times in

the process. The adoption of the plan and its review by

the district court and by the panel of this court all oc

curred at times when the Supreme Court was providing

little guidance about the legal bounds of such a plan. It

is therefore not surprising that in the district court the

judge and the school board were looking over their shoul

ders at the “ role model” theories espoused by the district

court in Wygant v. Jackson Bd. o f Educ., 546 F. Supp.

1195 (E.D. Mich. 1982). Britton, 593 F. Supp. 1223 (N.D.

Ind. 1984). On appeal, the panel majority, for which I wrote,

was most concerned with Janowiak v. Corporate City o f

South Bend, 750 F.2d 557 (7th Cir. 1984), vacated arid

remanded, 55 U.S.L.W. 3675 (U.S. Apr. 6, 1987), an af

firmative action case in which the same district court that

decided Britton had recently been reversed. The panel

majority certainly did not rely on a role model theory and,

in fact, expressly renounced reliance “ on any particular

theory of role modeling.” Britton, 775 F.2d 794, 800 n.8

(7th Cir. 1985). Subsequently, the Supreme Court reversed

Wygant in a series of opinions, none of which commanded

a majority, that present a confusing array of essentially

new law. 106 S. Ct. 1842 (1986). Among other things, the

plurality opinion soundly rejected the role model rationale.1 2

24 No. 84-2841

1 The panel opinion affirming the district court in this case is

found at 775 F.2d 794 (7th Cir. 1985). It contains an extensive

statement of the background of this case, including the facts of

past discrimination, and I rely on it here particularly in that re

spect.

2 A majority of the Justices in Wygant also rejected the require

ment in Jammhak that affirmative action programs “be based upon

findings of past discrimination by a competent body,” 750 F.2d

at 561. See infra pp. 26-27. The Court has recently vacated the

judgment in Janowiak and remanded the case to this court “ for

further consideration in light of Johnson v. Transportation Agency,

[107 S. Ct. 1442 (1987)] and Wygant v. Jackson Bd. o f Educ., [106

S. Ct. 1842 (1986)].”

28a

Soon thereafter, the Supreme Court decided four more cases

in which it upheld the validity of race-conscious remedial

plans and further elaborated on the standards for accept

ance. Johnson v. Transportation Agency, 107 S. Ct. 1442

(1987); United States v. Paradise, 107 S. Ct. 1053 (1987);

Local Number 93, Int'l Ass’n o f Firefighters v. City o f

Cleveland, 106 S. Ct. 3063 (1986); Local 28 o f the Sheet

Metal Workers’ Int’l Ass’n v. EEOC, 106 S. Ct. 3019

(1986). Because of the extreme fluidity of the law and the

consequent striking shifts in the relevance of various facts,

it would be much better practice to remand to the fact

finder—the district court—to determine in the first in

stance the disposition of this case in light of these recent

Supreme Court decisions. I therefore respectfully dissent

and join Judge Cummings and Judge Fairchild in their

dissents.

The plurality opinion here is at great pains to show that

this is a “ worse” case than Wygant and hence more de

serving of unceremonious reversal. In fact, now (and prob

ably even more clearly after further fact-finding in the

district court) this case is unmistakably different from

Wygant. In the district court and in the court of appeals,

the record in Wygant was unambiguously that of a “ role

model” case. The record there provided a basis for in

creasing the percentage of minority teachers only for the

purpose of furnishing enough role models for minority

children or, alternatively, to compensate for societal dis

crimination. By contrast, in the case before us, there is

solid record support for the school board’s concerns in in

stituting a plan to redress its own past discrimination

against black teachers in hiring.

Four of the five Justices voting to reverse in Wygant

expressly rejected the lower courts’ determinations that

the goals of providing role models and remedying societal

discrimination were sufficient to justify the challenged

layoff provision. 106 S. Ct. at 1847-48 (plurality opinion);

id. at 1854 (O’Connor, J., concurring). Seven Justices, how

No. 84-2841 25

29a

ever, stated (and the remaining two Justices did not dis

agree) that the elimination of the effects of a public body’s

own past or present discrimination is a constitutionally

valid purpose for that body’s use of a race-conscious rem

edy. Id. at 1848 (plurality opinion); id. at 1854-57 (O’Con

nor, J., concurring); id. at 1863 (Marshall, J., dissenting).

Justice O’Connor, who cast the decisive fifth vote, sum

marized what she viewed as the areas of Court “ consen

sus” in Wygant:

The Court is in agreement that . . . remedying past

or present racial discrimination by a state actor is

a sufficiently weighty state interest to warrant the

remedial use of a carefully constructed affirmative ac

tion program. This remedial purpose need not be ac

companied by contemporaneous findings of actual dis

crimination to be accepted as legitimate as long as

the public actor has a firm basis for believing that

remedial action is required.

Id. at 1853. Adoption of remedial measures does not de

mand a contemporaneous finding by a court or other body

that the public actor actually discriminated. Id. at 1848

(plurality opinion); id. at 1854-57 (O’Connor, J., concurring);

id. at 1863 (Marshall, J., dissenting); id. at 1867 (Stevens,

J., dissenting). As Justice O’Connor argues, requiring

public employers to make findings that they had in fact

illegally discriminated before they can undertake race

conscious remedies would obviously put a high price on

remedial measures. Such employers would have a rough

road to follow in fulfilling their constitutional duty to take

affirmative steps to eliminate the continuing effects of past

discrimination. Id. at 1855-56 (citing Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Green v.

New Kent County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968)). Of

the eight Justices who comment on this issue in Wygant,

those who demand the most of the employer would not

require a dauntingly rigorous showing. They would de

mand only that, if the lawfulness of a plan is later chal

lenged, the employer present the trial court with suffi

26 No. 84-2841

30a

cient evidence to allow the court to determine “ that the

employer had a strong basis in evidence for its conclu

sion that remedial action was necessary.” Id. at 1848

(plurality opinion).

The main reason the Supreme Court did not remand

Wygant to a lower court was that there the only evidence

of past hiring discrimination was contained in “ lodgings”

submitted by the defendant after the case had been brought

up from the Sixth Circuit. The plurality refused to consider

the “ non-record documents that respondent has ‘lodged’

with this Court,” citing “ the heretofore unquestioned rule

that this Court decides cases based on the record before

it.” Id. at 1849 n.5. The plurality said that, where the

defendant’s asserted purpose is to remedy its past discrim

ination, “ there is no escaping the need for a factual deter

mination below—a determination that does not exist [in

Wygant]." Id. In like vein, Justice O’Connor found that

it was unnecessary to remand because the layoff provi

sion there acted “ to maintain levels of minority hiring that

have no relation to remedying employment discrimina

tion.” Id. at 1857. She noted the obvious—that the

discrepancy between the percentage of black teachers and

black students, on which the defendant had relied in sup

port of its role model theory', was “ not probative of em

ployment discrimination.” Id.

Not only was the record in Wygant devoid of any evi

dence of past employment discrimination, but, in fact,

there had been two judicial findings that the school board

in Wygant had not engaged in past discrimination in em

ployment. A Michigan court had found that it “ ‘ha[d] not

been established that the board had discriminated against

minorities in its hiring practices. The minority represen

tation on the faculty was the result of societal racial dis

crimination.’ ” Id. at 1845 (plurality opinion) (quoting

Jackson Educ. Ass’n. v. Board o f Educ., No. 77-011484CZ

(Jackson County Cir. Ct. 1979)). Earlier, in a suit brought

by laid-off minority teachers seeking to require the Jack-

son Board to observe the race-conscious preferential layoff

No. 84-2841 27

31a

provision, a federal district court concluded “ that it lacked

jurisdiction over the case, in part because there was in

sufficient evidence to support the plaintiffs’ claim that the

Board had engaged in discriminatory hiring practices prior

to 1972.” Id. at 1845 (plurality opinion) (discussing Jackson

Educ. Ass'n. v. Board o f Educ., No. 4-72340 (E.D. Mich.

1976)). No wonder Justice O’Connor felt no need to re

mand Wygant for a determination of how the layoff pro

vision related to apparently non-existent past discrimina

tion in employment.

The situation in South Bend was markedly different.

The South Bend schools were racially segregated by stat

ute until 1949—only five years before Brown v. Board o f

Education—and continued as a dual system at least into

the mid-70’s. The Office for Civil Rights (the “ OCR” ) of

the then Department of Health, Education and Welfare

(“ HEW” ) conducted on-site reviews of the South Bend

schools in 1969 and 1975. Defendants’ Exhibit (“ Def. Ex.” )

M-3; Def. Ex. M-6. The OCR reviewed complaints it re

ceived about the South Bend School Corporation’s discrim

inatory practices as well as information supplied by the

School Corporation itself. Id. The OCR came down with

a clear indictment of the School Corporation in a series

of letters in 1975 and 1976. A letter dated March 13, 1975

described evidence that the School Corporation discrimi

nated against minorities in the recruitment, hiring and

promotion of teachers and that it maintained a dual school

system in which predominantly black schools received sub

stantially less financial and other support than predomi

nantly white schools. Def. Ex. M-6. The OCR wrote again

on October 6, 1975, bluntly conveying its finding that the

School Corporation had violated Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 by creating racially identifiable schools

and therefore had “ an obligation to undertake sufficient

remedial action to eliminate the vestiges of its racially

discriminatory teacher assignment policies and practices.”

Def. Ex. M-3, at 2. This letter ordered the School Corpo

ration to submit within forty-five days a plan to remedy

28 No. 84-2841

32a

its violations. By a letter dated March 8, 1976, the OCR

specifically required that the plan include assurances that

the School Corporation would maintain nondiscriminatory

practices for the recruitment, hiring and assignment of

teachers. Def. Ex. M-2, at 4.

On July 20, 1976, the United States District Court for

the District of Columbia ordered HEW to commence en

forcement proceedings against the School Corporation

unless HEW determined that the Corporation was in com

pliance with Title VI. Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp

1215, 1221, 1223-24 (D.D.C. 1976) (naming the School Cor

poration as one of twenty-six districts “ found in violation

of [Title VI] after HEW investigations, many of which

were very lengthy, as long as seven years in duration,

before being concluded with findings of default” ) (Brown

admitted as Def. Ex. M-7). Subsequently, the federal gov

ernment determined that the School Corporation had not

taken adequate corrective measures and filed suit alleg

ing that “ the South Bend Community School Corporation

. . . ha[s] engaged in acts of discrimination which were

intended and had the effect of segregating students and

faculty on the basis of race in the school system.” Def.

Ex. C-l, at 1 (consent order). The School Corporation

agreed to a consent decree on February 8, 1980. In a

subsequent opinion, the district court noted that the de

segregation plan adopted on February 21, 1981 “ was the

first comprehensive plan of its nature ever adopted for

the benefit of students attending the schools within the

defendant corporation. The filing of the Plan of Desegrega

tion came twenty-seven years after Brown v. Board o f

Education, during which period two generations of stu

dents passed through the school system.” United States

v. South Bend Community School Corp., 511 F. Supp.

1352, 1356 n.4 (N.D. Ind. 1981), affd, 692 F.2d 623 (7th

Cir. 1982).

The consent decree provided, inter alia, that “ [t]he

Board of School Trustees shall continue to pursue its pres

ent affirmative action hiring policies,” Def. Ex. C-l, at

No. 84-2841 29

33a

3, and report to the federal government for the next four

years “ the total faculty, by race, of the School Corpora

tion,” id. at 4. Thus, in 1980, when the provision at issue

here was adopted, the effect of past discrimination against

black teachers and job applicants was thought serious

enough to warrant the imposition of affirmative action pro

grams for hiring black teachers. These programs were to

be monitored by the federal government until the end of

1983. Here, with plenty of record evidence of past discrim

ination, the district court should be accorded an opportu

nity to determine whether the level of minority hiring was

closely related to the goal of correcting past discrimination.

The plurality opinion here seeks to deny much of this

background by pretending that history began only in 1972

(or perhaps 1978). The plurality opinion cites hiring sta

tistics achieved only under the federal lash in the 1970’s

as being somehow representative of the “ past” in South

Bend. This is like starting the history of slavery with the

Emancipation Proclamation. The Supreme Court has re

peatedly chastised the lower courts for ignoring history.

The Court has charged school authorities with a continu

ing affirmative duty to eliminate all vestiges of past racial

discrimination regardless of when the discriminatory acts

took place. In Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973), the Court stated:

The courts below attributed much significance to the

fact that many of the Board’s actions in the core city

area antedated our decision in Brown. We reject any

suggestion that remoteness in time has any relevance

to the issue of intent. If the actions of the school au

thorities were to any degree motivated by segregative

intent and the segregation resulting from those actions

continues to exist, the fact of remoteness in time cer

tainly does not make those actions any less “ inten

tional.”

Id. at 210-11. Similarly, in Green v. County School Bd.,

391 U.S. 430 (1968), the Court rejected a desegregation

30 No. 84-2841

34a

plan that would give all students the freedom to choose

a public school because the plan did not fulfill the school

board’s “ affirmative duty to take whatever steps might

be necessary to convert to a unitary system in which ra

cial discrimination would be eliminated root and branch.”

Id. at 437-38; see also Wygant, 106 S. Ct. at 1856 (O’Con

nor, J., concurring) (states have a “ constitutional duty to

take affirmative steps to eliminate the continuing effects

of past unconstitutional discrimination”) (emphasis in orig

inal); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ., 402

U.S. 1, 15 (1971) (“ The objective today remains to elimi

nate from the public schools all vestiges of state-imposed

segregation.” ) (emphasis added).

The plurality opinion, rather naively it seems to me, also

states that, although the School Corporation may have

engaged in racial “ steering” by assigning black teachers

to black schools, this has nothing to do with discrimina

tion in hiring. In fact, the lead opinion claims that segre

gating black teachers in black schools may improve their

employment prospects. No doubt this was true during the

many years when legally segregated schools in the South

provided the only market for black teachers. But atti

tudes, in most quarters at least, have changed markedly

since those Jim Crow days.

Under modem conditions, we may safely assume that

a dual school system presents an uninviting prospect to

black job applicants. When a school board maintains racial

ly identifiable schools, provides the black schools with less

financial and other support than the white schools and

staffs the black schools with black teachers who are given

much less opportunity for promotion than are white teachers

in the white schools, the school board sends a message

that “ blacks need not apply” for jobs. Systems where

blacks are treated equally obviously present more attractive

opportunities. The School Corporation failed to dismantle

its segregated system, ignoring the fact that “ [m]ore than

twenty years ago the Supreme Court expressed impatience

for what it considered to be intolerable delays in the face

No. 84-2841 31

35a

of its clear and unambiguous decisions,” Wade v. Hegner,

804 F.2d 67, 72 (7th Cir. 1986). Because of this foot drag

ging, the trier of fact could reasonably adopt a working

hypothesis that the resulting atmosphere of discrimina

tion produced fewer black teachers than would have been

the case under a constitutional regime.

The Supreme Court has employed an analogous infer

ence to justify the imposition of race-conscious remedies:

An employer’s reputation for discrimination may dis

courage minorities from seeking available employ

ment . . . . In these circumstances, affirmative race

conscious relief may be the only means available “ to

assure equality of employment opportunities and to

eliminate those discriminatory practices and devices

which have fostered racially stratified job environ

ments to the disadvantage of minority citizens.”

Local 28 o f the Sheet Metal Workers' Int'l Ass'n v.

EEOC, 106 S. Ct. 3019, 3036-37 (plurality opinion) (quoting

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800

(1973)). In Sheet Metal Workers, the plurality relied on,

inter alia, the trial court’s “ determination that the union’s

reputation for discrimination operated to discourage non