Motion for Summary Judgment Pursuant to RuIe 56

Working File

January 18, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Motion for Summary Judgment Pursuant to RuIe 56, 1983. aaf1cfdd-d392-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/49d015d1-8fb4-4169-b317-d6c36c147ee9/motion-for-summary-judgment-pursuant-to-ruie-56. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

RALPH GINGLES, et aI.,

Pla i nt if fs,

V.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, €t dI.,

Defendants.

-and-

ALAN V. PUGH, €t al.,

Plaintiffs,

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRTICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

a

V.

JAMES B. HUNT,

-and-

JR., et al.

Defendants.

No.81-803-CIV-5

No. 81-1066-CIV-5

No. 82-545-CIV-5

JOHN J. CAVANAGH, €t dI.,

Plaintiffs,

V.

ALEX K. BROCK,

-and-

et dI.,

Defenda nts,

RALPH GINGLES, €t dI.,

Def e nda nt- I nte rve nors .

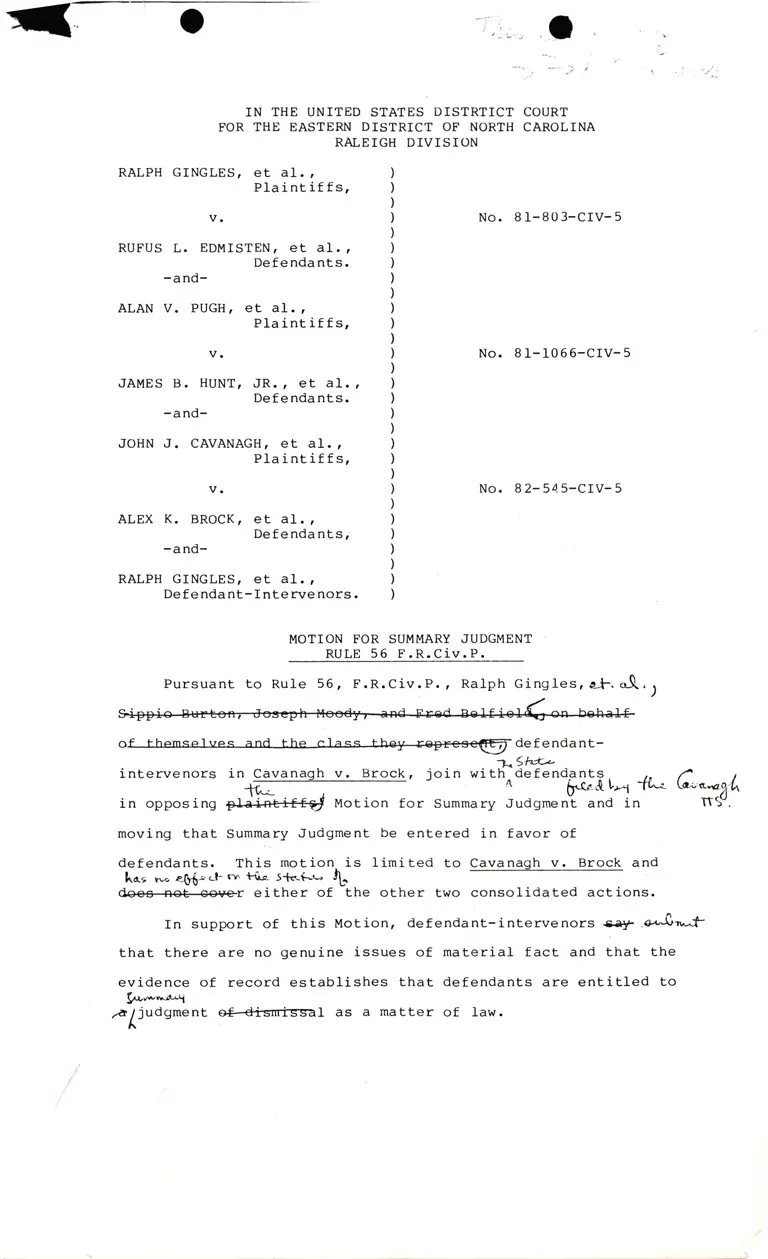

MOTION FOR SUMI4ARY JUDGMENT

RULE 5 6 F. R. Civ. P.

Pursuant to RuIe 56, F.R.Civ.P. , Ralph Gingles, ej-. "i.. )

6f thcmselwcq anrl the cl:cs they represe'Fdefendant-

1-Sh*-.intervenors in-r_@, join with defendants. ,. r-rki ;=:.';;_1""1"]'=""5i;:It r -fL{ *-rA'.L

in opposing plai-Hti#t, Motion for Summary Judgment and in fi

moving that Summary Judgment be entered in favor of

defendants. This motion. is limited to @ and

ka, ,* t$'$. cl- cn lrin 5*c'-(-l, LMeitheroftheothertwoconSo1idatedactions.

In support of this Motion, defendant-intervenors s:1r .c*.Sr^^f-

that there are no genuine issues of material fact and that the

evidence of record establishes that defendants are entitled to

tal**n*tpljudgment o€-+istrissal as a matter of law.

A

lo

/

This day of , 1993.

Respectfully submi tted,

J. LEVONNE CHAMBERS

LESLIE J. WINNER

Chambers, F€rguson, Watt, WaIlas,

Adkins & FuIler, P.A.

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

704/37s-8461

JACK GREENBERG

LANr CUISrnn

suite 2030

10 Columbus CircIe

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Def endant-Intervenors

{ ....

-+

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRTICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

RALPH GINGLES, et dI.,

Pla int if fs,

V.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, €t dI.,

Defe nda nts.

-and-

ALAN V. PUGH, €t aI.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., Et al.

Defendants.

-and-

JOHN J. CAVANAGH, €t dI.,

P1a i nt if fs,

No. BI-803-CIV-5

No. 81-I066-CIV-5

No. 82-545-CIV-5v.

ALEX K. BROCK,

-and-

et dI. ,

Defenda nts,

RALPH GINGLES, €t dI.,

Def e nda nt- I nterve nors .

DEFENDANT-INTERVENORS I ITTEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION

TO PLAINTIFFSI MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGIVIENT AND IN

SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTSI AND DEFENDANT-INTERVENORSI

MOTIONS FOR SUI\,IMARY JUDGMENT

I. Statement of the Case

-7" Gro-'*rt -rrr :{=3_ n

Jrftrintitfs i-*-++i-s.--ae+i-o# challenge the apportionment

of the North Carolina House of Representatives and of the

North Carolina Senate on the single ground that Forsyth

County is divided in contravention of Article II 53(3) and

S5(3) of the North Carolina Constitution. l/

On October I, 1981, the State submitted Article II

53(3) and 55(3) of the North Carolina Constitution to the

?rAttorney General of the United States pursuant to 55 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965r Ers amended, 42 U.S.C. S1973c

(hereafter "S5" or "S5 of the Voting Rights Act"). The

Attorney General interposed a timely objection on November

k

l,.^ Cq &x s

.Lrad ///r!-rtod b

30, re8r. rFi€fgniection eevered enar-rhe 40 of

iffJs:-

Gingles v. Edmisten( tna*-i-s.-+* black residents of North

|!1 l*^ti: cJL.-*

Carolinars I0O counties which are covered by 55. ditd-doee-

? u,{...^gq ta a- c.c'<rrutv h..-tc,},.,'z\q-l L" { .''

noffeii5i Forsyth CountV( North Carolina T= not f iled an

action for a declaratory judgme4t in the District Court of

a /o W '4t ^ ^"4, t" e'ffii,i'. L6A^f^,<-&-Q

the Distri-ct of Columbia" seekinOns5 preclearancgr.

Plaintiffs makes two arguments in support of their

motion for summary judgment. The first is that the Attorney

General's objection was not valid and is of no effect. The

second is that even if the objection is valid, the Stite

Constitution's prohibition aginst dividing counties is still

in full force and effect in the 60 counties not subject to

S5, including Forsyth County.

Defendant-Intervenors are the class of plaintiffs in

v$r.L cc-rs--'&c cl-6 6-CA

Carolina who are registered to vote.

agreeg with plaintiffs and defendants that there. are no genuine

/q

contendJ that defendants

law for the following

summary judgment.

are enti(lLa to judgment as a matter of

reasons:

l. This court does not have jurisdiction to review the

Attorney Generalts objection to Article II, S3(3) and S5(3)

of the North Carolina Constitution.

2. Even if this court does have jurisdiction to review

the Attorney Generalrs deLermination, the decision that the

adoption of Articre rr, 53(3) and 55(3) was subject to 55

preclearance is correct.

3. Those defendant-intervenors who live in counties

not covered by 55 are denied equal protection of the laws if

the legislature is prohibited from dividing those 60 counties

in apportioning the legislature but is not prohibited from

dividing the 40 counties which are subject to 55.

L

n

th-u''zY-

4.

^

Article II S3(3) and

they are not enforceable in 40

in the remaining 60 counties.

ss(3) are not severable/ ad if A

counties they are also unenforcable .(

5. In addition, defendant-intervenors adopt defendantsl

argument that Supremancy Clause, Article VI 52 of the

United States Constitution, justifies the division of Forsyth

lt4-eP-4'Q-

Couniy frf tnat division was necessary for the State to be able to

comply with one person-one vote requirements of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution.

II. Article II 53(3) and 55(3) of the North Carolina

Constitution have not been precleared under S5 of

. the Voting Rights Act and are not enforcable.

)k (s.,tn--/ t

I /Laintiffs assert, in support of their motion for

summary judgment, that the Attorney Generalrs November 19Bl

objection to adopt Article II 53(3) and 55(3) of the North

Carolina Constitution has no effect because the 1968 adoption

of the provision was not a change in election procedure

which was subject to the preclearance requirements of 55.

See Memorandum supporting plaintiffsr motion for summary

4 jud .t'@) ---,argument does not entitle lllaintif f s

(J-"r**ut, judgment n.""u"Vt€l this court is without jurisdiction

!"_=":._*__1" d9*terminalion of tle_attorney ceneraL2And N)q \

the provisions in question were a change in voting procedures

subject to the requirement of 55 preclearance.

1,,\e

. .'t (.?l

^ A. This b-ouEt doeb-ot nave jurisdiction to review the

Attorney Generalrs determination under S5 that the adoption

of Article II 53(3) and 55(3) of the North Carolina Constitution

cons t i tu ted a ch a nge *fi".*J f"*-c0;-2.--*,e.<e- '

Article II, 53(3) and 55(3) of the North Carolina

Constition W enacted by the General Assembly during the

Lg67 Session, Chapter b4O 6 the Session Laws of Lg67,

and ratified by vote of the people in 1968. fn September,

1981, Gingles v. Edmisten,3I-803-Civ-5, was filed in this

Court. gjngleg is, in partr a ffi proceeding 4 ,..ar^--g

U

/

5

J

;fr*,-U l'l C u',*ffi*^'9

tui y'/

un-i.e+l -etrtms; that the /prov i s ions4 ,/,

prec learance requireme nts

@ 55 preclearance. See Gingles v. Edminsteri

Complaint, Count One, Paragraph 24-46, and Prayer for Relief,

Paragraph 3. On October l, 198I, North Carolina eernefe+e+

a4-^^:rttc^/ fib7

+t*-eubsrissi-o+-e€ ther,amendments to the Attorney General of

the United States under the procedure specified in 42 U.S.C.

S1973c. By letter dated 30 November 1981, the Attorney

General interposed objection to the two proposed amendments.

See Stipulation, t[1, filed February 22, L982 in Gingles v. Edmisten

and Pugh v. Hunt, 8I-1066-Civ-5, and Attachment A thereto..->

I

'hry;;*

,ral >/.V nuuvrrrsl sEtrslqr. v\rLslrrrrrs., Lrrqu^Lrrs -Lru.

;oo.(JfJ[rg,

AJ,_!*.n" does not make a response on the merits but insteadfiotif ies

n-fvl- the submitting authority, Id.

"/

Since, in this instance, the Attorney General did not notify

the State that the submission was inappropriate but ruled on

the merits, the Court must presume that the Attorney General

concluded that the adoption of these provisions was a change

which reouired Dreclearance.

\. 'Stot* t4,?-e rw-rryw r v- a_

Once the- constitutional amendments Mto

I

I

I

the Attorney General for 55 review, this Court ros+-+€-St -

. jurjsciiction.

f^",!,L,l *a +1"-:@ ".o^U; ,1**/d

,44

A b "n3oiil.9"nforceme9

-f inal anC-.trot-. rev"ie*ab-le -by--eh,i

entry- way f,or the proris-iorrg fo.

tdntthe State t€ f ifela declaratory judgment action in the

District Court for the District of Columbia seeking a de

.t

p {-AQ*t"./' !e+(.-,*l-

C* , w"to:D ->t us b;t (tns

J

1

\t rtL ''

that the Attorney Generalrs failure to interpose a timely

objection under S5 of the Voting Rights Act is not reviewable.

Id. at 506. In Yorris v. Gressette, the Attorney General, /---\

.tl-LL44.+i4-^4 +J" 4<- - /

South Ca"rolina Senate reapportionment -61 /"4zaad e A" /sb.".i^^.,L/4-^ *A -A.n -/+reehu^s,c-the South Carolina Uistrict Court hed.&ttnd the

4^/a-d A

reapportionment in questioX not in violation of the Fifteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution. Plaintiffs,

who were black citizens residing in South Carolina, claimed

br^Z)that the Court decide whether

,*4,/,.;2#i* W, m q,'^nl';H'r: ffis ?# : ^d

a r d

inWSCerm+nat*enY The Supreme Court concluded

that "Congress intended to preclude all judicial review of

the Attorney Generalrs exercise of discretion or failure to

act." Id. aL 506-507 and n.24. It is important to note

that the Court reached this decision dispite the fact that

it deprived the plaintiffs in the action of aII access to a

judicial forum

i

On the same day that the Supreme Court decided Morris v. I Gressette

nqvo detetmination that the provisions do not hav\the

,--/ \

purpose-wilI not have the effect of denying or abrjy'ing the

A CrQ,

right to vote on account of rE6. - This Court is without

4a

jurisdiction to review^validity of the Attorney Generalrs

determination or objection.

The United States Supreme Court first considered the

reviewability of the Attorney Generalrs S5 determinations in

t'lorris v. Gressette,432 U.S.49I (1977). The Court held

supra, it also decided Briscoe v. BeII,432 U.S. 404 (f977),

holding that the Court does not have jurisdiction to review

the determination of the Department of Justice and the

Bureau of the Census that a jurisdiction is subject to the

provisions of 55 in accordance with 54(b) of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965r ds amended, 42 U.S.C. S1973b(b). Section

4(b) provides that the determination is not reviewable. The

-{ Q A.*r^.t"DistrictCourtandCoutofApp-a1she1dthat1ffitcou1d

/

The Su

prec Iu

supra, have been followed in

establish the principle that

any exercise of discretion by

Court reversedrreasoning that Congress intended to

view in order to effectuate the purpose of the Act /

a variety of

no Court has

the Attorney

supra, and Briscoe v. BeIl,

circumstarrces to

jurisdiction to review

General under 55 of

156 (1980), the Court dismissed for lack of subject matter

jurisdiction the portion of the Complaint which claimed

that, in interposing an objection, the Attorney General applied

55 to the City of Rome in an unconstitutional manner. The

Court noted that it is of no consequence whether the challenge

is couched in terms of improper procedure or in terms of

lmproper gubgtantlve result. Id. at 38I, rr.2. The Court held

'IT]his Court is without jurisdiction over plaintiffs' challenge

to the procedures used by the Attorney General in deciding to

interpose an objection to the City of Romers proposed electoral

ah

dranges. " Id. at 381. The Court noted the distinction between

the holding of Morris v. Gressette, supra, that a Court cannot

review the failure to object, and the request in City of Rome

to review the entry of an objection. The Court concluded that

the legislative scheme of the Voting Rights Act, when viewed

as a whore, compels the concrusion that the decision of the

Attorney General to interpose an objection was also not intended

4n .*-*./^,^^^

(fu g+b %-oX-)(v

reviewr\to determine if the Act had been correctly interpret/ed

as a matter of law,

Dreme-

a20-qie

to eradicate discrimination with aII possible speed, Id. at 4L0r YIS

-?he=Cou-ri

+#.6mrr

The decisions on Morris v. Gressette,

the Voting Rights Act.

--

In Harris v. BeIl, 562 F.2d 772, 774 (5th Cir. 1977) ,

the Court held that it is wholly without jurisdiction to

determine whether the Attorney General has followed federal

regulations in withdrawing an objection under S5. In Harris v. BelI,

as in Morris v. Gressetter plaintiffs were, thereby, wholly

deprived of judicial forum.

More importantly, in City of Rome v. United States, 450

F.Supp. 378 (D.D.C. L978), aff'd on other grounds 446 U.S.

to be the subject S ,uoi$r review. Instead, the only relief

from a decision to object is for the covered jurisdiction to

seek a declaratory judgment de novo in the District Court for

the District of Columbia. Id. at 381.

The fact that the plaintiffs in Cavanagh v. Brock cannot

initiate a de novo action in the District of Columbia

District court is not determinative. The private praintiffs

in Morris v. Gressette, supra, and in Harris v. Bel1, supra,

r./< j-

*i+I similarly lef t without a judicial forum. See also

Pitts v. Carter, 380 F.Supp. 4 (N.D.Ga. L974') in which the

Court held that it had jurisdiction to enjoin procedures

which had not been precleared but no jurisdiction to allow

enforcement of a procedure to which an objection had been

interposed. Id. at 7-8. In PitLs v. Carter, the party

seeking enforcement of the provision to which the Attorney

General had objected was, as here, a private individual with

no alternative judicial forum.

FinalIy, in Dotson v. City of Indianola, Miss. t 52L

F.Supp. 934, 943 (N.D. Miss. 19Bt) , af f 'd U.S. , 73

L.Ed.2d L296 (L982), the Court held that it does not have

jurisdiction to review the Attorney General's authority to

preclear part of a S5 submission while objecting to another

part of the same submission. Plaintiffs in Dotson were

private citizens seeking to hold City officials in contempt

for enforcing the submitted annexation after the Attorney

General objected. The City defended by saying that the

objection letter was not varid because the Attorney Generar

was required to preclear or object to the whote submission.

The Court cites Morris v. Gressette, supra, and City of Rome,

supra, in concluding that it cannot review either the Attorney

Generalrs failure to object or his objection.

i9In tho case a**a*rd, the Attorney Generalts determination

under 28 CFR S51.33 that the submission was appropriate and

'/

that the provisions were changes subject to 55 preclearance

is not reviewable by this Court just as the determinations

in Morris v. Gressette, supra, Citv of Rome, supra, and

Dotson v. Citv of Indianolar suprErr were not subject to

judicial review.

Defendant-Intervenors have been able to locate only one

possible exception to this chain of cases, Garcia v. Uvalde County,

455 F.Supp. I0I (w.D. Tex. I978), af f rd 439 U.S. 1059 (1979).

In Uvalde, the Court held that it had jurisdiction to determine

whether or not the Attorney Generalrs objection letter vras

timely. This decision is not probative of the question at

hand. S5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. S1973c, provides

in pertinent part:

Provided, that such qualification, prerequisite,

sEnAara, practice, or procedure may be enforced

without such proceeding Iin the District Court for

the District of Columbial if the qualification,

prerequisiter standard, practice, or procedure has

been submitted by the chief lega1 officer or other

appropriate official of such State or subdivision

to the Attorney General and the Attorney General

has not interposed an objection within 60 days

after such submissionr...

Thus, in an action by private citizens to enjoin enforcement

of a procedure to which the Attorney General had objected,

it was appropriate for the Court to determine whether or not

the Attorney General had interposed an objection within 60

days after the submission. It was not reviewing the substance

or procedure of the objection letter but only determining

whether or not there was an objection letter within the time

specified in the statute. In this case, in contrast to

Garcia v. Uvalde, there is no dispute that there was an

objection letter interposed within the requisite 60 days.

There is nothing in Garcia v. Uvalde that suggests that once

the court determines that there was a timely objection

rerrer, ir .^{zrffittla", Generail s dererminarion - tu-t^(/,&q"*fu /\ - _2

[ftt

*Gfrln"

submitted provisions constituted a change within f

the meaning of the Act.

L

Nor is the holding in 4llsn__v._ttqEg Eoard of Electigns,

393 U.S. 544 (1969), to the contrary.

held that local three-judge courts have

enforcement proceedings to determine if

enactment is subject to the provisions

In AIlen, the Court

jurisdiction in a 55

the particular state

of 55 and therefore,

must be submitted for approval before enforcement. Id. at

560. This does not suggest that once the provision has been

submitted a private party can litigate to determine if the

submission was required.

The reasoning of the Court in Al1en, that there is a

private right of action to enforce 55 and that local three -

judge district courts have jurisdiction in enforcement

proceeding to determine if preclearance will be required,

does not logically extend to a post-submission review of

whether or not a submission which has already been made was

required.

In Allen the Court noted that 55 was designed to protect

minority citizens from denial of the right to vote because

an authority fails to submit a new enactment for preclearance.

Because the statute was designed to protect that class of

citizens, and because the staff of the Attorney General was

deemed to be too small to adequately monitor the changes in

all submitting jurisdictions, implication of a private right

of action was necessary to make the Act more than a empty

promise. The individual citizen was, therefore, held to

have standing to ensure that his local government complies

with the 55 approval standards. 393 U.S. at 556-557.

In contrast, in the context of the case at handr plaintiffs

seek to avoid 55, not to enforce it. Plaintiffs are not

members of the class which the Act is designed to protect.

Indeed, they are not even residents of a covered jurisdiction.

The Attorney Generalrs staff has already performed its task

.*

of examining and investi2r{Oating the submission. There is no

q

question of the Attorney General's capacity to accompJ-ish

the purpose of the Act. In short, there is nothing in Allen

that suggests that a private litigant should be.lU. to undo

the determination of the Attorney General that the submission

was appropriate and that the sections of the state constitution

in question constituted a change.

In conclusion, intervenors point out that this is not a

situation in which no judicial determination of whethe, #-

vfrsf S5 preclearance was required was available. fn response

to the Complaint in Gingles v. Edmisten, defendants could

have argued that the enactment of the North Carolina Constitution's-ffi (fu 4*..^!J Mbprovisions was not a change and # submitbj+g9--

the provisions for preclearance until this Court determined

that preclearance was required" Defendants did not choose

that route. The submission has been made, and the Attorney

fu ,1 b-qz

General has both determined that there was a change and.ha:s

c@ThisCourtdoesnothavejurisdictionnow,atthe

request of third parties, to review the accuracy of the

Attorney Generalr s determination.

B. The adoption of Article II SS3(3) and 5(3) were

changes subject to S5 preclearance.

Assuming, Srsuendo, that this Court f,ud iurisdiction to

determine the validity of the Attorney Generalrs objection,

the objection is valid.

[tr-

Section 5 of the Voting Rights applies whenever a

covered jurisdiction, "shall enact or seek to administer any

practicerfpracticefor procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November 1, L964,.. . "

The adoption of the provisions of the North Carolina Constitution

that prohibit dividing counties in the creation of legislative

districts constitut{.r,"r,q"Ofithin the meaning of S5.A

I. The History of the North Carolina Constitutions's

provisions concerning apportionment of the General AssembIv.

Prior to November I, 1964, the North Carolina Constitution provided

I

I

I

J

t"/

that the 120 members of the House of Prespresentatives were apportionec

such that each of the 100 counties had at least one representative.

The remaining 20 representatives were divided among the most

populous counties. North Carolina Constitution Article II, S6

(1875); Drum v. SeaqelI, 249 F.Supp. 877 t 880 (M.D.N.C. 1965).

Thus, representatives were apportioned by county instead of by

population. Under these provisions, according to the 1960 census,

on November l, 1964, there brere 1r counties which were at reast

50t black in popuration and one more which was over 50? non-

white. (See United States Census, North Carolina, Table 28,

attached as Exhibit A. ) Thus eleven majority non-white representative

districts were required by the pre-1964 provisions of the North

Carolina Constitution.

In 1965, the Court in Drum v. Seawell, supra, held this

method of apportionment to be violation of the one person-

one vote requirement of the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Z4g

F.Supp. at BB0.

In 1966 the General Assembly, without changing the

North Carolina Constitution, adopted a new apportionment ofg#

the House of Representatives. Chapter 3 of th{.Session

Laws of 1966. In L967, the General Assembly adopted the

questioned constitutional provisions which were ratified by

the voters in 1968.

Prior to November L, L964, the North Carolina Constitution

provided for the 50 members of the Senate to be apportioned

such that, "each Senate District shall contain, as nearly as

may be, an equal number of inhabitants, excluding aliens and

Indians not taxed, and shall remain unattered until the

return of another enumeration, and shalI at all times consist

of contiguous territory; and no County shall be divided in

the formation of a Senate District, unless such county shal1

be equitably entitled to two or more Senators.,, North

rl

Carolina Constitution, Article II, S5 (fB6B) (renumbered

Article II, S4 in I875) (emphasis added).

The Court in Drum v. SeaweII, supra, did not declare

this provision unconstitutional but did hold that the particular

apportionment then in effect violated the equar protection

clause. 249 F.Supp. at B81.

The General Assembry adopted a new apportionment of the

Senate in 1966. Chapt er 1- ot the .Session Laws of 1966.

The provision of the North carorina constitution prohibiting

the division of counties in apportioning the Senate was

adopted in L967 and ratified in 1968 at the same time that

the House provision was adopted.

2. The L967 Amendments to the North carorina constitution

were changes subject to S5 preclearance.

It has been recognized that in enacting 55, Congress

meant "to reach any state enactment which altered the election

law of a covered State in even a minor way. "

Doughertv Countv Ga. v. Whitet 439 U.S. 32, 37 (1978);

Allen v. State Board of Elections,393 U.S.544,566 (1969).

ail i1 gL (**"r<;o ly k *d-,t ).-- (+y-f- 4 Qy,?-+ro h n- cL-J\_ c7 \'r /-1a25.1r'a.t .The continuihg intent of Congress t.o cbver aII changes' <)

relating to elections, those which are complex as weIl as

those which are subtler -ris reflected in the legislative

V;iUl3,qnb\."-*-r,1edl l"lr.r. ffi "4- bh is tory ot' AigrlJ9fP-- elg!pf*+o*f f# the--ercpe:i=1la-tri4n-

@*,

@+T Voting Rights Amendments of L982, Sec. 2, p. L.

97-205,96 stat. r3l; Report of the committee of the Judiciary

of the United States Senate on S.B. L992, Report No. 97-4L7, at

9-L2 (copy attached as Exhibit B) (hereafter "senate Report,').

There can be no serious question that 55 of the Voting

Rights Act covers the apportionment of state legislatures.

McDanieI v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981); United Jewish Organizations

v. Carey,430 U.S. L44 (L977); Georgia v. United States,4Il

u.s. 526, 535 (1973) . rndeedr the senate Report notes, ,'The

continuing problem with reapportionments is one of the major

concerns of the voting Rights Act." senate Report at L2, n.31.

r1,

C.il&'

In fact, thefrLpo.t at p. L2 specifically notes the Attorney

Ptt -

Generalrs objection to the redistricting of the North Carolina

General Assembly as evidence of the continuing need for 55.

4-- *.*P1aintiIt.sFeno,however,thattheL967amendmentsto

the State constitution prohibiting division of counties were

not "different from Ithose] in force or effect on November 1,

L964" because the practice had never been to divide counties.

This argument is counter to common sense and applicable case

Iaw.

I

As a matter of common sense, changing from an apportionment

scheme which apportioned representatives to counties without

qS..-Jt.-^, !L^! ^^^L L^--^ ^.-r-ril;{regard to population,(reOuired that each county have dt o_ t*:;

+ oa.u-h ,9.tn-tnu4*-C& d-cf-.! t 'xl*t-"J;cr.

, ffil*least one representative, and req+LiJad fat le-ast eleven ru

aLmajority non-white districts to(scheme which apportions

according to populationr prohibits division of counties, and

has no assurance of any majority black representative districts

Ci-l.9t. Lks

-is/tfre adoption of a method of apportionment which is dif ferent.

Whether the difference had the purpose or effect of diluting

minority voting strength, is, of course, not for this Court

to determine. See Ivlorris v. Gressette, 430 U.S. 49L (1977);

part IIA, .W..

Similarly, changing the Senate apportionment provisions

from a rule which specifically allows the division of some

counties to a rule which specifically prohibits the division

of any county is different. In fact, under the pre-1967

rule, the division of Forsyth County, which is entitled to

two or more senators, would have been specifically aIlowed.

rH-u* +. "HAa {^r*frlq

It defies logic to- say that the State i+*eaded/to amenO

irs constirurro"{S:#ft"f ffi{irr"...,. and did nor

t\

change it.

Case law supports the conclusion that adopting a rule

which incorporates a prior practice is a change subject to

(,'..dt.,.2u* 'h c"ot WAlv a!*h-t*

the provisions of 55. fnel+di+Jg @re of an election

process in a new form of government was held to be subject to

t)

55 preclearance in Citv of Lockhart v. United States, Civil

Action No. 80-364 (3 judge court) (O.D.C. IgBl), appeal

pending _U.S. ,50 U.S.L.W. 36g5il1982) (copy attached

as Exhibit C). In City of Lockhart, the City changed from a

"general lah/" government with a three member commission with

numbered posts to a "home ru1e" government with a five member

city council, also with numbered posts. The Court held that

the inclusion of numbered posts in a new election scheme was

a change and that the inclusion of that feature was subject to

S5 preclearance. City of Lockhart, sIip. op. at 7.

The Court based its ruling primarily on two reasons.

First, the City had "abolished completely the commission

form of government and substituted in its stead an entirely

new form of city government with an entirely new election

scheme." Id. at 8. SimiIarly, even though the pre-1964

apportionment of the North Carolina House of Representatives

used whole counties as building blocks, that method of

apportionment \,rras completely abandoned and an entirely

different method, based on population rather than on loca1

government representation, was substituted. In the Senate a

system that allowed legislative discretion as to the division

of counties was abandoned for a system which eliminated all

legislative discretion.

\\

L/ AYArticle II S53(3) and 5(3) nrovf,F:

2/

Hereaf terras used in this lvlemorandum, "Attorney

General" will refer to the Attorney General of the United

States acting through his designee rthe Assistant Attorney

General, Civil Rights Divisionrin accordance with 28 C.F.R.

s5I.3.