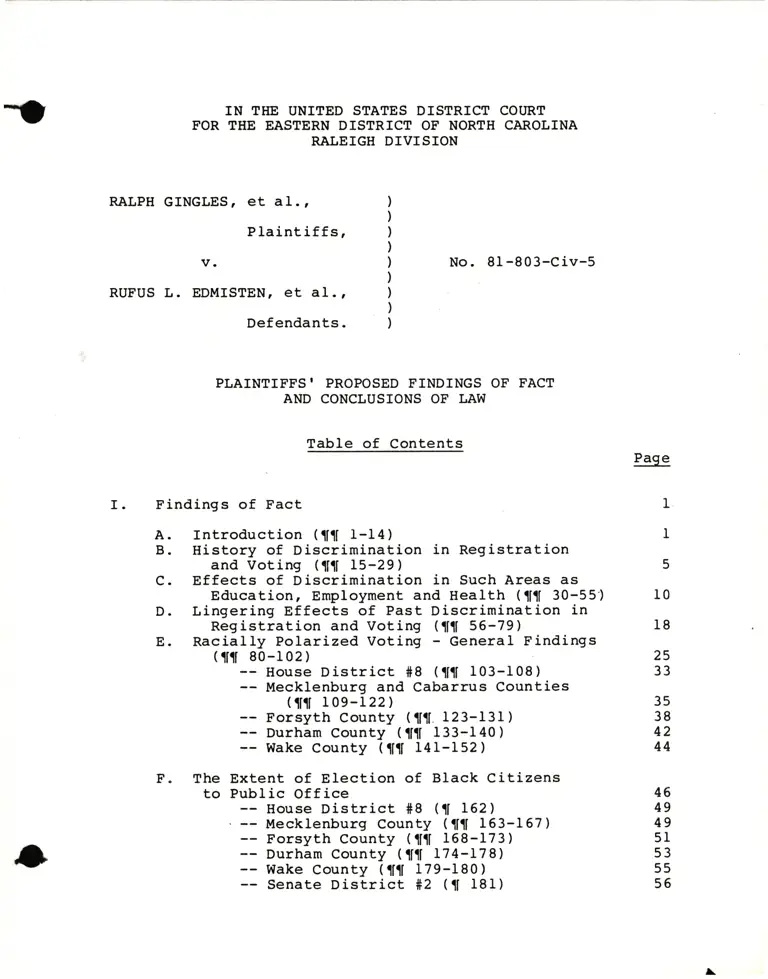

Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 1983. b75ec989-db92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b25e9f6-b3e7-4cbc-9912-d37c4baed3b8/plaintiffs-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

IN TTIE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FoR rnE EASTERN

B*lT;$rSloiloRrH

CARoLTNA

RALPH GINGLES, et dI.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, €t aI.,

No. 81-803-Civ-5

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS I PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT

AND CONCLUSIONS OF I,AW

Tab1e of Contents

I. Findings of Fact

A.

B.

c.

D.

E.

Introduction ( tttt f -14 )

History of Discrimination in Registration

and Voting (tttl I5-29)

Effects of Discrimination in Such Areas as

Education, Employment and Health (tttf 30-55)

Lingering Effects of Past Discrirnination in

Registration and Voting (tttt 56-79)

Racially Polarized Voting - General Findings

( tttt 80-102 )

-- House District #8 (tttt f 03-108)

-- Mecklenburg and Cabarrus Counties

( ttT L09-L221

-- Forsyth County (ttlt 123-131)

-- Durham County (Ttl 133-140)

-- Wake County (tttt I4f -I52)

The Extent of Election of Black Citizens

to PubIic Office

-- House District #8 (tl L62)

. -- trlecklenburg County (tttt 163-167)

-- Forsyth County (tttt 158-173)

-- Durham County (ttlt 174-178)

-- Wake County (tftt 179-180)

Senate District #2 (tt 181)

Page

25

33

35

38

42

44

46

49

49

5I

53

55

56

I

I

5

l0

18

El

\

Table of Contents (contrd)

Use of Racial Appeals (tttt f82-I94)

l,tajority Vote Requirement and Unusually Large

Districts

-- Anti-Single Shot and Numbered Seats(tt les )

-- Majority Vote Requirement

( tt?fr I96_2r s )

-- UnusualIy Large Election Districts

( ttT 2L6-2L8

I. Multi-member Districts Decrease Minority

Participation (tttt 2L9-2331

J. Responsiveness (tttt 233-24L'l

K. The Po1icy for the Use of Multimember

Districts Is Tenuous (lttt 242-274)

L. Facts Concerning Senate District #2

( tttt 27s-313 )

II. Conclusions of Law

A. Jurisdictional and Procedural (tttt 1-5)

B. Statutory Claims (ttfl 6-15)

C. Constitutional Claims (tttt 15-21)

D. Rel ief ( tttf 22-251

III. Appendix

Plaintiffs' Exhibits 56-70A

Guide to Abbreviations:

G.

H.

Paqe

57

62

62

62

66

67

72

74

84

97

97

98

r02

103

Plaintiffs use the following abbreviations in their cita-

tions to the record:

T. Tria1 Transcript

Dep. Deposition

Stip. Stipulation ( set out in Pre-Tria1 Order)

Pl. Ex. Plaintiffsr Exhibit

D.Ex. or

Def. Ex. Defendantsr Exhibit

Stip. Ex. Exhibit to Stipulations ( filed with Pre-TriaI

Order)

Pugh Ex. Exhibit of Pugh Plaintiff-Intervenors

App. Appendix

l1

r. FINDTNGS OF FACT

A. Introduction

1. The North carolina Generar Assembly ( "the General

Assembly" ) consists of the ltouse of Representatives ( rthe

House") which has 120 members and the senate which has 50

members. (Answer to X 24 of Complaint)

2- rn 1981, the General Assembly enacted a new appor-

tionments of its House and Senate representative districts in

light of the 1980 census. (Answer to paragraph 37 of complaint)

These apportionments were enacted in accordance with Article

II S 3(3) and 55(3) of the North Carolina Constitution which

prohibits the division of counties in the formation of House

and senate districts. (Answer to complaint paragraphs 26,

27, 29, 30; paragraph 18 of Answer)

3- The apportionment of the House, chapter 900 of the

session Laws of 1981, had a range of population deviation of

23.5t and had no districts which were majority black in

population. (stip. 12i stip. Ex. ci This apportionment was

substantially the same as the r97r apportionment. (Lilley

Dep. at 12-13).

4. The apportionment of the senate, chapter 921 of the

session Laws of 1981, had a range of population deviation

of 22.7* and had no districts which were majority black in

population (stip. 13; stip. Ex. F). This apportionment was

identical to the 1971 apportionment of the senate. (Rauch

O Dep. ar 76)

5. on september L6, 198r, this action was fired alreging,

I

inter a1ia, that the apportionments of the Hous.e of Represen-

tatives and of the senate violated the one person, one vote

reguirement of the egual protection clause, unconstitutionally

and i11egally diluted the voting strength of brack citizens,

and that Article rr, ss 3(3) and 5(3) of the North carolina

constitution were being enforced without having been pre-

cleared pursuant to S 5 of the Voting Rights Act ( "S5" ).

(Stip. 14 )

5. fn response to the filing of the Complaint in this

action, defendants submitted Artiele II, 53(3) and S 5(3) to

the Attorney General of the united states for preclearance.

(Answer to paragraphs 88, 89 of Supplement t,o Complaint;

st,iP. 15 )

7. In October, 1981, the General Assembly reconvened

to enact new apportionments of the House and senate. chapter

1130 of the session Laws of 1981 was enacted reapportioning

the House, but the senate did not adopt a new apportionment.

The range of popuration deviation of the House apportionment

was 15.5t. Chapter 1130 was enacted in accordance with

Article rr, S 3(3) of the North carorina constitution. (stips.

18, 19; Stip. Exhibit K; Answer to paragraph 90 of Supplement

to Complaint)

8. By letter of November 30, 1981, the United States

Attorney General interposed objection pursuant to S 5 of the

Voting Rights Act to Article II, S 3(3) and S 5(3) of the

2

North Carolina Constitution stating, 'Our analysis shows that

the prohibition against dividing the 40 covered counties in the

formation of Senate and House districts predictably requires,

and has led to the use of, large muLti-member districts. Our

analysis shows further that the use of such rnulti-member dis-

tricts neeessarily submerges cognizable ninority population

concentrations into larger white electorates.r (Stip. 22i

Stip. E M).

9. Subsequently the United States Attorney General

interposed objections to Chapter 821 (the Senate aPportionment)

and Chapter 1130 (the House apportionment). (Stips. 23, 25i

Stip. Ex. N, O).

10. The General Assembly reconvened in February, 1982,

and in April, 1982 to reapportion the House and Senate. (Stip.

32, 371 The apportionments enacted in these sessions divide

both 55 covered and non-covered counties. See Chapters 4 and 5

of the Session taws of the First Extra Session (Stip. Ex. R,

U); Chapters 1 and 2 of the Session Laws of the Second Extra

Session (Stip. Ex. Zt CC). Counties were divided only for the

purposes of lowering population deviation or of obtaining

S5 preclearance. (Stip. 51 ) No districts which are majority

black in population or in voter registration were formed in

counties not covered by 55 of the Voting Rights Act. (Grofman,

T. 28r31)

1 1. The apportionments

the following districts with

indicated (Stip. 57):

of the House & Senate include

population and registration as

3

Senate (SD) or

House District (tID)

HD *36 (Mecklenburg)

HD *39 (part of Forsyth)

HD *23 (Durham)

HD "21 (wake)

HD *8 (Wilson-Edgecombe-

Nash )

SD "22 (Mecklenburg-

Cabarras

District

Mecklenburg Co. (House)

Forsyth Co.

Durham Co.

hlake Co.

Wi I son-Edgecombe-Wash.

Mecklenburg (Senate)

t of Population

that is Black

26.5

25.1

36. 3

21 .8

39. s

24.3

t of Registered

Voters that is

Black as of 10/4/82

18.0

20.8

28.6

15. 1

29.5

15. 8

12. It is possible to create single member districts

wholely within each of these districts which are majority

black in population and whieh are contiguous, reasonably

compaet and have a population deviation of less than plus

or minus 5t as follows:

t Population that iq Black

District *1 66.1 (PI. Ex.4)

District *2 71.2(PI. Ex.4)

70.0 (PI. Ex.5)'10.9 (P1. Ex.6 substitute)

57.0 (PI. Ex.7)

62.7 (Pl. Ex.8)

70.8 (Pl. Ex.9

13. Senate District *2 currently has a population which

is 55.1t black but voter registration whichr ds of October 4,

1982, tas only 46.2$ black. (Stip. *57) It is possible to

draw a district in roughly the same area, using townships,

which is contiguous, reasonably compactr has a population

deviation of -.8t, and has a black population of 50.7t.

(Pl. 8x.10).

14. Named plaintiffs in this action and the plaintiff-

intervenors are adult residents of North Carolina and are

registered voters. (Stips. 5, 5) They represent the class of

all black residents of North Carolina who are registered

to vote.

B. Eistory of Discrimination in Registration

15. North Carolina has a long history of discrimination

against black citizens. (T. 308) In North Carolina black

citizens gained the right to vote after the civil yrar, and

together -with white Republicans, controlled the Iegislature

from 1868-1875. fn 1875, Democrats, who were whiter E€-

gained control of the government and took steps to reduce

black political participation. Nevertheless, black males

voted and were elected to office during the remainder of

the Nineteenth Century. (T. 230)

15. In 1890, the populists forned a coalition called the

Fusionists, with black and white Republicans. The Fusionists.

gained control of the legislature in 1894 and made changes to

make it easier for blacks to hold local office and to register.

In addition, the Fusionist Legislature enacted legislation

favorable to economically disadvantaged blacks and whites. (T.

231 )

17. fn response, the Democrats determined to break up the

coalition by disfranchising black voters. The tactic used

was to persuade white voters that North Carolina was under

Negro rule. Using an overtly racist 'White Supremacy' pro-

paganda campaign (e.9. PI. Ex. 22, 231 , violent intimi-

dation, and corruption in votirg, the Democrats regained

control of the legislature in 1898. The 1898 legislature

adopted constitutional amendments providing for a pol1 tax,

5

a literacy test for voting, and a grandfather clause for the

literacy test designed to Iimit its disfranchising effects

to blacks. (T. 2321 233t 237)

18. By using the same tactics of overt racist propoganda

(e.9. PI. Ex. 241 , violent intimidation, and corruption in

ballot counting, the Democrats were successful in having

these disfranchising amendments adopted by the voters in

1900. Thereafter black voter registration and participation

in the political process virtually disappeared until 1930.

(T. 239, 242)

19. The literacy requirement for voting continued to be

used in North Carolina until at least 1970. In 1961, Bazemore

v. Bertie County Board of Elections, 254 N.C. 398 (1951)' the

North Carolina Supreme Court struck down the practice of

requiring registrants to write the North Carolina Constitution

from dictation but upheld the requirement of ability to read

and write the North Carolina Constitution to be administered to

all applicants of uncertain ability. (Stip. 85) Phyllis Lynch

testified that she was required to copy a portion of the North

Carolina Constitution when she registered to vote in Mecklenburg

County in 1968. (T. 429 ) The earliest instructions that the

State Board of Elections could locate instructing the county

boards to stop using the literacy test were dated December 28,

1970 (in which the instruction was buried in a set of instruc-

tions about registration of 18-20 year olds)(D. Ex. 41), and

one written in L972 which refers to a iluly 30, 1970 memo as well

as the December 28r 1970 memo. (D. Ex. 42; Spearman T. 578)

6

Although Representative Allen Adams testified for the State

that the fact that Wake County was released from S 5 coverage

in 1965 meant that it had not used a literacy test to dis-

criminate, that testimony was limited to Wake County, and Rep.

Adams did not know what time period the determination covered.

(T. 1361- 2, 1364)

20. Between 1930 and 1948 the percentage of blacks who

rrere able to register to vote under the literacy test and

poII tax increased from 0t to 15t but no black was elected

to public office. (T. 242) In 1960 only 39.It of the black

voting age population registered to vote, compared to 92.It

of whites. (P1. Ex. 38) By 1971 , 44.4t of blacks rrere regis-

tered compared to 60.6t of whites. (P1. Ex. 38) This disparity

in registration continues today. See PI. 70, infra.

21. Additional evidence of the continued disfranchising

effect of the literacy test and the resulting low level of

participation of black citizens in the political process is

the overtly segregationist or tokenist stands taken by many

politicians beginning 1950, when the civil rights movement was

just beginning (T. 244). Dr. Harry Watson testified to this

result through 1972 when he stopped his investigation. (T. 276-7i

324).

22. Prominent North Carolina politicians beginning with

Willis Smith, who successfully ran for the United gtates Senate

in 1950, (T.245-245t Pl. Ex. 25), and including Alton Lennon

and Kerr Scott in the race for the United States Senate in

7-

1954 (T. 247-8, PI. Ex.26li I. Beverly Lake and Terry Sanford

in the election for Governor in 1950 (T. 255-7, Pl. Ex.27li

Lake, Dan Moore, and Richardson Preyer in the race for Governor

in 1954 (T. 259-60, PI. Ex. 29, 3O); Robert Scott and ilim

Gardner in the election for Governor in 1968 (T. 270-271i

Pl. Ex. 33, 34) i and Jesse Helms in his successful bid for

the United States Senate in L972 (T. 274-6, Pl. Ex. 37'),

each took either overtly segregationist stands, advocated

token integration to maintain the statug guor or expressed

opposition to civil rights 1aws. These segregationist positions

were neeessary because the participation of black citizens

in the electoral process was so low that black voters could

not injure the candidates who took these positions, and the

racial prejudice of white voters was such that it was necessary

for politicans to oPPose integration in order to get elected.

(T. 256-7, 26Lt 27lt 276-71

23. fn addition to the use of the literacy test and poII

tax to disfranchise black citizens, the State of North Carolina

adopted other election mechanisms that hindered the ability

of black citizens to elect representatives of their choice.

North Carolina enacted an anti-single shot voting law in

1955 which was enforced in specified municipalities and counties

until it was declared unconstitutional in 1972 in Dunston v.

Scott, 336 F. Supp. zOG (EDNC ]1972). (Stip. 91, Answer to Inter-

rogatory *20)

24. fn addition, concurrently with the adoption of the

multi-member district plan for apportioning the General

8-

Assembly in L967, the General Assembly adopted a system of

numbered seats for specified legislative districts. (T.

302t 304-5) Nunbered seats were used in House or Senate

districts including, at various times, Mecklenburg Forsyth,

Durham, Wilson, Edgecombe, Nash, Bertie, Hertford, Northampton,

Halifax, Martin, Washington, Chowan and Gates Counties.

(Answer to Interrogatory 2ll Numbered seats were used for

election to the legislature until they were declared unconsti-

tutional in 1972 in Dunston v. Scott, -W.. (Stip. *92't

25. Numbered seats prevent single shot voting. (Stip. 92)

This was the avowed purpose for adopting them (T. 302), and

they were adopted over the expressed objection of black

leaders that numbered seats were aimed at disfranchising the

Negro and diluting the Negro vote. (T. 303-4)

26. fn addition to statewide laws which limited the ability

of black citizens to register and use their vote effectively,

the time and place for registering to vote in the various

counties was limited to the central Board of Election office

and to hormal working hours. These restrictions, which

lasted until the late 1970rs, had the effect of preventing

black citizens from registering to vote because of lack of

transportation to the central office and because black people

who work during normal office hours could not leave work to

register to vote. (T. 555, 704-707 | 745)

27. Individual towns and counties also took official

actions which were discriminatory in effect and purpose. For

example, the first black Alderman in the City of Wilson was

elected in 1953 from a single-member district which was 50t

black in voter registration. He was re-elected in 1955 and was

9

named Chairman of the Budget Committee. (T. 697-8) Between 1955

and 1957 the City Council changed its method of election to an

at-Iarge election system. The result tras that, running at

large, the black Alderman was defeated in 1957. There was no

black member of the Wilson City Council thereafter until 1975.

(T. 699 )

28. The Court finds that the City of Wilsonrs changing its

method of electing its City Council had the effect of diluting

minority voting strength and preventing the election of black

councilmen, and was adopted for that Purpose.

29. Thus, North'Carolina has a history of official dis-

crimination which directly affected the ability of black

citizens to register, voter and participate in the political

system. This official policy of diserimination began with

the disfranchising amendments of 1900 and lasted until pre-

vented by federal law in the early 1970rs. (T. 308)

Effects of Discrimination in Such

C. Areas as Education, Emplovment and Health

30. North Carolina has a history of official action

designed to create and maintain segregation in all areas of

life. Offieial segregation was almost total at the end of the

19th Century and even Fusion legislature took no action to

end official segregation. (T. 232)

31. Between 1900 and 1950 segregation continued to be

almost total. (T. 240t 243') Statutes prevented marriage be:

tween people of different races and provided for segregation

of fraternal orders and societies; seating and waiting rooms

10

for railroads and all other common carriers; cemeteries;

prisons, jails, and juvenile detention eenters; institutions

for the blind, deaf and mentally i11; public and employee

toilets; schools and school districts; orphanagest eolleges;

and library reading rooms. (P1. Ex. 42) With the exception

of the statutes relating to schools and colleges, most of

these statutes were not repealed until after 1965, and many

as late as 1973. (p1. Ex. 421

32. Public schools in North Carolina were officially

segregated by race until Brown v. Board was decided in 1954.

Although in 1900 Governor Aycock had promised to improve the

schools as part of a literacy test campaign, the increased

funding went only to schools for white students, thus increas-

ing the already present disparity in education available to

white and black students. (T. 24L) The schools were not only

separate but they were also unequal.

33. When Brown v. Board was decided. in 1954, Governor

Umstead and all other major politicians opposed the decision and

vowed to limit its effect in North Carolina. (T. 250)

34.' The Staters response to Brown v. Board was to decen-

tralize the school system to make court challenges more

difficult (T. 251)i to threaten black parents that schools

would be closed if they demanded integration (T. 253); and

to require black students individually to apply for admission

to white schools. (T. 2541

35. The result was that by 1960 only 226 black students

attended formerly all white schools in the whole state (T.253),

11

and by the end of the 1960 | s virtually all schools remained

almost all white or all black (T. 267). school systems vrere

not integrated until they were required to be by federal court

order in the earry 1970rs following the united states supreme

courtrs decision in swann v. tr{eckrenburg county Board of

Education in 1971. (T. 267, GlI, 701)

36. North Carolina has a high degree of residential segre-

gation which was promoted by official acts. Between 1930

and 1950 various cities such as charlotte and Greensboro had

official zoning laws or other ordinances limiting where

black peopre could reside. The veterans Administration and

Federar Housing Administration cooperated by restricting

the areas in which they.would make loans based on race. (T.

243) Other official acts such as the relocation of

brack residents displaced by urban renewar, the location of

public housing, and zoning ordinances perpetuated residential

segregation. (T. 265-6t 649, 609-12, 775)

37. Although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended official

policies promoting discrimination in residentiar roans, and

produced token integration in rarge apartments and develop-

ments, the degree of residential segregation remained very

high. (T.268)

38. North Carolina also has a

private discrimination in employment.

1960rs there was almost no employment

by the state government. Employment

history of official and

In the late 1950rs and early

integration, including

opportunities for blacks

12

in the textile industry, the staters largest industry, were

limited to outside or janitorial jobs. Other major industries

such as tobacco and t,rucking limited blacks to employment in

the lowest paying positions. (T. 263-4, 703)

39. The State Employment Security Commission cooperated in

this employnent discrimination by referring people to prospec-

tive jobs on the basis of their race. (T. 265)

40. The effects of this history of discrirnination remain

evident throughout North Carolina in the areas of educationt

housirg, and employnent as set out in paragraphs 39-55 below.

39. Since almost no sehool systems were integrated until

after 1970, almost all black adults educated in North Carolina

who are over 30 years old attended inferior segregated schools

for all or most of their primary and secondary education,

and the first classes of children who attended integrated

schools for their whole education are just beginning to

reach voting age.

40. In addition, black adults over 25 are substantially

more likely than whites to have completed less than 8 years of

education (34.5t of blacks compared to 22.0t of whites) and are

substantially more likely than whites not to have attended any

schooling beyond high school (29.3t of whites compared to 17.3t

of blacks) (Stip. 81)

41. Some school districts remain segregated for all Prae-

tical purposes. For example, the Durham City Schools are

90t black while the Durham County schools are about 30t black.

13

(T. 647t The Roanoke Rapids School System is almost all

white while the Halifax County School System is almost all

black. (T. 776t 8441

42. As recently as 1983, the Rocky Mount Board of Education

adopted a classroom assignment policy which resulted in the

creation of some all black classrooms. (T. 74ll

43. Despite the integration of public schools' black stu-

dents continue to fail the North Carolina Competency Test at

substantially higher rates than do white students in every

school system in the counties in question. (Stip. 78) .B1ack

students are improving on standard reading tests at a faster

rate than white students are, but black students at each

grade level tested stil1 did worse in 1982 than white students

did in 1977. (Stip. 79) Similarly, while black students in

Mecklenburg County are narrowing the gap between their scores

on the California Achievement Test and white studentsr scores,

black students at each grade level sti1l scored substantially

lower in 1983 than white students did in 1978. (P1. Ex.

708) Thus past discrimination in education continues to

affect not only the current voting age Population but also

the current school age population.

44. Housing segregation in North Carolina remains very

strong and virtually all neighborhoods in the districts at

issue are racially identifiable. (T. 268, 436, 596, 648, 703,

739, 840-1, 1215-18) In addition, black households are twiee

as like1y to be renting as opposed to buying their homes (T.

398; Pl. Ex. 55-70A) and are substantially more likely to be

14

living in overcrowded housirg, housing with inadequate plumbing

O (stip. 83) or substandard housing. (T. 594-5)

45. According to witnesses for both plaintiffs and defendants,

blacks continue to bear the effects of past and current dis-

crimination in employment with blacks holding lower paying jobs

than whites. (Little T.611; Butterfield T.703-4i Belfie1d

T.743; ltalone T.1215-1218; Hauser Dep. at 38-39i Green T. 1251)

Blacks also consistently have a higher incidence of unemployment

than whites. (Stip. 68)

46. Even in state government blacks are concentrated in

lower paying and lower skilled jobs. A higher Percentage of

black employees is employed at every salary level below

$12r000 per year and a higher percentage of white employees

is employed at every salary level above $12r000. (Stip. 69,

7I, 72 and P1. Ex. 71)

47. A report produced by the North Carolina Office of State

Personnel on patterns of pay in North Carolina State Government

shows that white government employees are paid more than blacks

even when education, years of aggregate service, supervisory

position and age are held constant. (Pl. Ex. 71; T.406)

48. The North Carolina General Assembly itself enploys

disproportionately few black employees, and those who are

employed are employed in low paying jobs. Thus, for the

professional staff 2 out of 49 (4t) of professionals are

black and 1 of 20 (5t) of clericals are black. (Answer to

Interrogatory 12A). Of the non-professional and clerical

staff, only 24 out of 299 (8$) rrere blaek in 1983. Of these

15

9 were housekeepers, 3 are on the Sergeant at Arms staff, I

was on the [Iouse Clerkrs staffr and the other 11 were secre-

taries to black Representatives and the black Senator and

chosen by them. (Stip. 99)

49. The result of the disparity in employment is that

blacks are three times as like1y as whites to have an income

below poverty leveI (30t v. fOt), the black mean income is

only 54.9$ of the white mean income; and white families are

over twice as likely as black families to have an income over

$20r000. (T. 398-9, Pl. Ex. 70A)

50. In addition, 25.It of all black household units have

no vehicle available compared to 7.3t of aII white household

units. (P1. Ex. 70A) This has the obvious effect of di-

minishing the ability of black citizens.to have the trans-

portation necessary to either register or vote. (T. 686,

705, 712, 77Ol

51. All available indicators of health indicate that black

residents of North Carolina are more likely to be in bad

health than whites. The infant mortality rate is the stan-

dard measure of health used by sociologists. (T. 400) The

infant mortality rate is approximately twice as high for

non-whites as for whites statewide in North Carolina (Stip.

73) and in each of Mecklenburg, Forsyth, Durham, Wake, Wilson,

Edgecomb and Nash counties. (Stip. 741 In addition, the

death rate is higher for non-whites than for whites (Stip.

75) and the life expectancy of non-whites is shorter than

the life expectancy of whites. (Stip. 77)

16

52. For all socio-economic measures reviewed, the so"io-l

economic status of blacks in North Carolina is lower than

the socio-economic status of whites. (Luebke T. 402') This

is true for the whole state and for every county in question

individually. (T. 411) (See Appendix A to these findings,

Pl. Ex. 56-70A). The ratio of blacks who were poor compared to

whites who were poor is highest in Chowan, Nash, Mecklenburg ana t

Wilson Counties. (T. 411)

53. North Carolina remains segregated not only in its

residential patterns (See X 44 above) but also, according to

witnesses for plaintiffs and defendants in its voluntary associa-

tions such as churches, civic clubs, social clubsr and country

clubs. (Lynch T. 435; Little T. 596i Lovett T. 648i Malone T.

1216; Butterfield T. 702i Belfield T.742t 76L-763i Ballance

T.84Ii llauser Dep. at 8t371

54. Because of the disparities in education, incomer €IIt- I

t

ployment, housing, and health, the black community has special

needs not in conmon with the white community. In each of the

districts at issue, cohesive, geographically identifiable black

neighborhoods exist which share common political and socio-

economic interests premised on these disparities. These common

needs give rise to the need for black representatitives who have

an awareness of these conmon problems and who have a first

hand understanding of the needs of the black community and whom

black voters feel free to approach. (Lynch T.445t Little

T.594-5; Hauser Dep. 36-37, 39; Lovett T.652-53; Halone T. L216,

t2L9; Butterf ield T.'ll.7 i Belf ield T.753; Ballance T.846, 852)

17

55. The lower socio-economic status of black citizens lessens

their ability to participate in the political process, (Luebke

T.402-3i Arrington T.801). This factor contributes to the

inequality of opportunity of black citizens to elect represen-

tatives of their choice.

D. tingering Effects of Past Discrimination

In Registration and Votinq

56. As discussed in paragraphs 15-29 above, official

discrimination in registration and voting, primarily through

use of the literacy test, resulted in depressed levels of

'registration of black citizens in North Carolina through

1970. Although there is no evidence of the use of the literacy

requirement since 1970, this past discrinination continues

to affect the level of black participation in the political

process as set out in paragraphs 57-79 below.

57. After 1970, the leve1 of black registration remained

depressed due to inaccessibility of voter registration and

fears and misapprehension of black citizens concerning the

registration process. The inaccessibility resulted froro

limitations of registration to the central elections office

(T. 555, 704, 745) r dDd resulting transportation problems

(T. 705t 745), limitation of precinct registrars to registering

by appointment in their homes (T. 7461, and limitation of

registration to normal work days and hours. (T. 655, 705)

The fears and misapprehensions included fear of having to

take a test, fear that the black citizen's employer would

disapprove of his registering (T. 556), and fear of the

18

Courthouse registration facilities (T. 705-6).

58. The result was that by 1981, only 42.7* of the black

population of voting age was registered to vote compared to

53t of the white voting age population. (Spearman T. 511 )

59. fn November 1981, after this action was filed, Robert

Spearnan was asked by the Governor of North Carolina to

become chairman of the State Board of Elections. One of the

primary concerns of the Governor was the under registration

of North Carolinats black citizens. Spearman shared this

concern. (T. 510-11; 544-5)

50. Spearman and the State Board of Elections have taken a

variety of actions to encourage or require local Boards of

Elections to make registration more accessible for blacks

and others.. 1982 was named Citizens Awareness Year and a

special effort was made to publicize registration oppor-

tunities during this year. (T. 51I-528)

51. Whether the State Boardrs Citizens Awareness Year

would succeed depended in large part on the voluntary cooperation

by local Boards of Elections. (D. Ex. 3, T. 550) For example,

while State law previously permitted precinct registrars to

register voters out of their precincts (T. 512), thus enabling

voter registration at churches, picnics and other places

where people gather (T. 7071, many loca1 Boards did not al.low

their precinct registrars to register voters outside their

precincts. (T. 707, 547) Although some loca1 Boards removed

the restrictions in L982

the State Board finall.y,

Spearmanrs request (T. 525, 550),

1982, sought legislation to require

at

in

19

local Boards to allow out-of-precinct registration. (T. 550).

62. Another example is that while state law allows the

appointnent of special registration commissioners, it only

requires the appointrnent of two, and some local Boards appoint

only the ninimum. (T. 708, 547-8)

63. fn a variety of waysr loca1 Boards of Election con-

tinued to take actions which made black registration and

participation difficult. (T. 709-10; 551-2; 563:ee)

64. Some previous efforts to increase voter registration,

such as registration in libraries and banks, were not success-

fu1 at reaching the bulk of black citizens who are not

registered. (T.474)

65. Black groups in several counties, in particular Durham

and Wilson, had sought to have registration opportunities

increased prior to the State Boardts efforts in connection

with Citizenrs Awareness Year and had met with resistance

from their local Boards. (T. 553-5, 656-7, 704-5, 707-8)

55. This resistance to easing accessibility of voter regis-

tration is exacerbated by the fact that only 12t of the

members of County Boards of Elections are black. (T. 579)

For exanple, despite the efforts of Durham blacks, the Durham I

Board of Elections remains all white. (T. 555, 660-662)

67. During Citizens Awareness Year, a popular black can-

didate, Mickey Michaux, was running for Congress from the

Second Congressional District. Voter registration drives were

conducted in the black community in conjunction with his

candidacy. Michaux lost in the second primary. fn the

20

counties in which he was running, (Durhamr Nash, Edgecombe,

Wilson and Halifax) almost all the gain in black registra-

tion occurred before the second primary. Thus, the gains in

these counties in 1982 seem to be as attributable to Michaux's

candidacy as they are to the efforts of the State Board.

(T. 573-4r PI. Ex. 14)

68. One of the most effective ways to encourage black parti-

cipation and registration is for black candidates to be able to

be elected. The election of all white candidates makes black

citizens believe their participation is futile. Conversely,

when elections have been conducted in which a black candidate

has a good chance of success, black participation has increased.

Examples are when the Charlotte City Council changed to single-

member districts, and when Michaux ran for Congress. (Reid 476,

478, 489i Butterfield 709, 712, 732i Spearman 573-4; Belfield

753i Moody 773t

59. There remain actual barriers to registration of black

citizens such as unavailability of registrars (Belfield

747-8; Lovett 6791r and lack of transportation. (Belfield

T. 75gt 747) There also remain psychological barriers to regis-

tration, particularly in older black citizens, some of whom

are illiterate, who fear eittrer that they will have to take

a test to register, who believe registration will be a

major problem, who are afraid their employer will disapprove,

or who believe they should not be making trouble. (Lovett

T. 653-4, 590; Butterf ield T.728, Belf ield T.'7 47 i Lynch T. 432,

46L-2; Ballance T. 848-50 | 864; Moody 7941 A tradition of not

21

voting is the result of past election practices. It affects

younger black citizens who are sometimes unfamiLiar with the

processi many blacks still believe their participation is

futile. (Lovett T. 590; Butterfield 710-1I, 729; BaIlance

864-55 ) .

'lO. The percentage of the black voting age population which

is registered to vote continues to be less than the percent

of white voting age population that is registered. In

October of 1978, 1980r ?Dd 1982 in the State as a whole and

in each of the counties in question, the respective percentages

are as follows (Registration figures taken from Answers to

Interrogatory *I divided by voting age PoPulation taken from

Plaintiffsr Exhibit 89):

Percent of Voting Age Population

Registered to Vote

L0/78 L0/80 L0/82

Whol.e State

Mecklenburg

Forsyth

Durham

ltake

Wilson

Edgecombe

Nash

Bertie

Chowan

Gates

Hal i fax

White B1ack

51.7 43.7

7r.3 40.8

55.8 58.7

63.0 39.4

6L.2 37.5

50.9 36.3

63.8 37 .9

6L.2 39.0

75.6 45.0

71.3 44.3

80. g

56. 8

68.2 50.4

'72.0 41.2

77 .O 54.l.

77.4 53.9

83.9 77.8

62.'1 53.1

64.2 43.0

74.6 60.0

74.1 54.0

93.5 82.3

67.3 55.3

White Black White Black

70.1 51.3 66.7 52.7

73.8 48.4 73. 0 50. 8

76.3 67 .7 69.4 64. r

70.7 45.8 55.0 52.9

76.0 48. 9 72.2 49 .7

55.9 40. 9 64.2 48. 0

73. 5

40. 9

22

72.0 50.4

Hertford

Martin

Northampton

Washington

75.6

69.3

72.4

74.3

56. 5

49.7

58.5

62.8

81. I

76.9

'17.0

82.2

62.5

55. 3

63.9

66.0

68.7 58.3

7L.2 53.3

82. r 73.9

75.6 67.4

71. While the efforts of the State Board of Elections in

Citizens Awareness Yearr combined with the volunteer activities

of black organizations (T. 640, 473-4, 707)t and the efforts

of black candidates to improve black registration have caused

some narrowing of the gap between black and white registration,

there remains a substantial gaP between black and white regis-

tration statewide (P1. Ex. 40; T. 283-4), and in every county in

question except Gates. (See ParagraPh 7O above)

72. while the level of black registration is gradually catch-

ing up with white registration (D.8x.52, 14), there still exists

a substantial gaP in white and black registration. There is an

even greater gap when the percentage of black registered voters

who turn out to vote is considered (T.4771.

73. Even defense witnesses Representative Adams and Mr.

Spearman concede that after Citizens Awareness Year was over,

the under registration of blacks in North Carolina remained

unacceptable. (T. Adams 135711 T. Spearman 575-7)

74. This gap is the lingering effect of past official dis-

crimination in registration combined with current socio-economic

factors and a sense of futility engendered by the pervasiveness

23

Ilertford

Martin

Northampton

Washington

75.6

69.3

72.4

74.3

56. 5

49.7

58. 5

62.8

81.8

76.9

7'7.0

82.2

62.5

55. 3

53. 9

66. 0

68.7 58. 3

7I.2 53. 3

82. 1 73.9

75.6 67.4

Citizens Awareness Year, combined with the volunteer activities

of black organizations (T. 640, 473-4t 707r, and the'efforts

of black candidates to improve black registration have caused

some narrowing of the gap between black and white registration,

there remains a substantial gap between black and white regis-

tration statewide (P1. Ex. 40i T. 283-41, and in every county in

question except Gates. (See paragraph 70 above)

72. While the level of black registration is gradually catch-

ing up with white registration (D.8x.62, 141, there still exists

a substantial gap in white and black registration. There is an

even greater gdp when the percentage of black registered voters

who turn out to vote is considered (T.477t.

73. Even defense witnesses Representative Adams and Mr.

Spearman eoncede that after Citizens Awareness Year was over,

the under registration of blacks in North Carolina remained

unacceptabe. (T. Adams 1357; T. Spearman 575-71

74. This gap is the lingering effect of past official dis-

rimination in registration combined with current socio-economic

factors and a sense of futility engendered by the pervasiveness

23

of prior practices which make black participation less likely.

(See Is 15-29, 55 above)

75. Although the General Assembly passed legislation in

1983 to improve accessibility of voter registration (T. 534-5),

the Court cannot speculate what effect it will have and no

evidence was presented that it will eliminate the gap between

black and white registration in the immediate future. (T.

730-732? 462-3, 486)

76. In addition, newly registered voters are less like1y to

vote, and newly registered black voters are less likely to

continue to participate if black candidates 1ose. (Reid, T.

47 6-477 )

'17. Black citizens are less likely to have been selected

for leadership positions in integrated civic affairs. They

have, thus, been denied the opportunity to establish the

credentials and visibility which would make them more accept-

able to the white community. (T. 433, 435) In addition, the

perception that black candidates have to be able to appeal to

the white community limits the pool of blacks who are willing

to run. (T. 442, 443, 834)

78. Other facts which make it less 1ike1y that blacks will

turn out to vote include the practice of farmers in the North-

eastern part of the state of requiring their employees to work

extra. long hours on election day (T. 849t 850), the drawing of

gerrymandered precincts in the City of Wilson in which black

voters are required to travel into the white community to vote

(P1. Ex. 87i T. 711-12), and the lack of access to vehicles,

24

and therefore transportation, which is three times more preva-

lent among black households than white. (PI. Ex. 55-70A;

T. 585-6 i 7701

79. Thus while some progress has been made, black citizens

in North Carolina continue to bear the effects of past discri-

mination in registration and voting which diminishes their

ability to participate in the political process (T. 322') and

contributes to the lack of equal opportunity to elect candi-

dates of their choiee.

E. Racially Polarized Voting - General Findings

80. Racially polarized voting occurs when white voters and

black voters vote differently. Racially polarized voting is

used synonymo]:sIy with racial block voting in political

science literature (Grofman T. 5Ql and the terms are used

synonymously in these findings.

81. Dr. Bernard Grofman testified on behalf of plaintiffs

concerning the extent of racially polarized voting in the

counties in question. Dr. Grofman is a Professor of PoIi-

tical Science at the University of California at frvine. He

has extensive experience concerning the analysis of voting

patterns and minority concerns in reapportionment issues.

(T. 19-24, PI. Ex. 1) He was received by the Court as an

expert in comparative election systemsr apportionment and

minority representation issues, statistical methodology' and

voter turnout. (T. 25)

82. fn order to determine the extent of racially polarized

voting in the multi-member legislative districts in question,

25

Dr. Grofman analyzed all the elections for the General Assembly

in which there were black candidates in tt{ecklenburg, Durham,

Forsyth and Wake Counties, elections for the House of Represen-

tatives in Wilson, Edgecombe and Nash Counties, and elections

for the senate in cabarrus county for the election years 1978,

1980, and 1982. fn addition, since there rrere not enough

legislative elections in Wilson, Edgecombe and Nash Counties,

Dr. Grofman analyzed two other county-wide elections with black

candidates in each of those three counties. (T. 51-54) In

total he analysed 53 sets of election returns (considering

primaries and generals separately) stemming from 32 election

contests. (T. 212-216l-

83. llr.Grofman condueted two different analyses of each

election: an extreme case analysis and an ecological regression

analysis. (T. 54) These two nethods are standard in the

literature for analysis of racially polarized voting. (T.

54). The purpose of these analyses is to determine the extent

that white and black voters vote differently from each other. (T.

ss)

84. Defendants challenge Dr. Grofmanrs analysis on t,hree

grounds. The first is that an extreme case analysis done

alone can be misleading since voters who live in racially

mixed precincts may behave differently than voters in ra-

cially segregated precincts. (T. 1382) Eowever, in this

instance, DE. Grofman did not conduct only an extreme case

analysis. The regression analysis considers the behavior of

the voters in mixed precincts as welI. In addition, in

almost all cases the results of the extreme case analysis and

26

the regression analysis conform extremely closely. (T. 1441;

Pl. Ex. 13-18) Because the extreme case analysis is standard in

political science literature and because it produced almost

identical results to the regression analysis, the Court accepts

it as probative.

85. The second challenge is that Dr. Grofman made no

exact count of voter turnout by race. (T. 1383) The only way

to determine these exact numbers is to count each voter regis-

tration card for each election and note the race of each

person who voted. There is no example in political science

literature or in the case law for requiring this precision and

defendantsr expert, DE. Hof.eller, has never used this method

exhibit 12, qhichr dt pages 3-8, describes Grofmanrs metho-

dology for estimating turnout. (T. 1441-I443) Hofeller could

notT therefore, know whether Dr. Grofmanrs method of estimating

turnout is flawed and the Court will not discount Dr. Grofmanrs

analysis on this basis.

86. The defendantsr third criticism of Dr. Grofmants

analysis is that there were two apparent mathematical or typo-

graphical errors. (T. 1383) The Court finds that these two

errors, out of the thousands of results calculated by Dr.

Grofman, do not shed doubt on the accuracy of the overall

analysis. (T. 1437 |

27

87. A standard measure of racially polarized voting is

the correlation between the number of voters of one race and

the number of voters who voted for a candidate of specified

race. (Grofman T. 60; Hofeller T. 1445) An analysis of voting

showing correlations above an absolute value of .5 is relatively

rare, and correlations above .9 are almost unheard of. (T.

60-51 ) A11 correlations calculated by Dr. Grofman had an

absolute value between .7 and .98 with most above .9. (T-

80) The Court, therefore, finds that there was racially

polarized voting in each of the elections analyzed. (Ilofeller

T. 1451 )

88. Grofman also determined that the racially polarized

voting was statistically significant at the .00001 level.

This means that the probability of these results occurring

by coincidence is less than one in 100r000. (T. 80, 151)

Defendantsr expert agrees with the eonclusion that the racially

polarized voting was stat,istically significant in each of

the elections analyzed (T. L446')t and the Court so finds.

89. Dr. Grofman further analyzed the election results

to determine whether the polarization of the voting was substan-

tively significant. He defined substantively significant to

mean that the voting was sufficientlv polarized that the result

of an individual e erent if it

had been held with onl white voters as compared to onIY

black voters. (T. 195, 206) Using this definition he found

28

substantively si

eneral

the Durham and Wake County House elections in 1982. (T. 213)

Both of these elections had incumbents running. (T. 2i-4t 99)

fn addition, in the Durham district, because only two white

candidates ran for three seats, a black candidate had to win the

primaryr dnd in the general election there was no opposition.

(T. 205, 209 )

90. Dr. Grofman further concluded that there was substan-

tively significant racially polarized voting considering the

elections he analyzed as a whole beeause there was no election

in which a majority of white voters voted for a black candidate

(T. 162)r and because of the smal1 number of individual elections

(2 of 32') which did not have substantively significant racially

polarized voting. (T. 222-2231

91. More specificallyr on the average 81.7t of

voters did not vote for btack candidates in prinary

(T. 80, 216) .

92. fn general elections, white voters almost always rank

black candidates either last or next to last among candidates

except in very predominantly Democratic areas, in which white

voters rank the black candidate last among Democrats. With few

exceptions, this is true in primaries as well. (T. 81i Pl. Ex. 11,

App. 3, Table 21. Furthermore, approximately 2/3 of white voters

will not vote for a black candidate in " ,"n"J.1ection even

after that candidate has survived the Demoeratic primary and the

only choice is to vote for a Republican or no one. (Tr. 216)

white

I

elections

t

election to be one election).

29

93. In none of the elections analyzed did a black candidate

receive votes from a majority of white voters in either a

primary or general election. (T. 81; Pl. Ex. 11, App. 3l

Table 1) This indicates that polarization is severe and

persistent. (T.81)

94. The proportion of white voters who are willing to-

vote for a black candidate in multimember districts is not

properly compared to the proportion of white voters who will

vote for a black candidate in a single seat election. (T. 215-2161

95. Whlle incumbency modifies racial polarization of the

voting, it does not eliminate it. (T. 82) Black elected

incumbents have successfully sought re-election, but no black

incumbent has received votes from a majority of white voters,

even when the election lras essentially uncontested. (PI. Ex.

11, App. 3, Table 1)

95. In addition, black incumbents in office by virtue of

appointment rather than election have been uniformly unsuccessful

in their re-election bids with less than one- third of white

voters voting for each of them. (T. 83; Pl. Ex. 11, APP. 3,

Table 1)

g'l-. The elections analyzed demonstate that Republicans

will vole for white Democrats but not black Democrats. (T. 84)

This puts black candidates at an additional disadvantage. Com-

bined with the racial polarization within Democratic voters,

the result is that, in a general election, if there is a black

candidate and if any Democrat loses, it is the black Democrat

and not a white Democrat who loses. (T. 83-84)

30

98. The racial polarization is more disadvantageous to

black candidates than to white candidates because there are

fewer white voters who vote for black candidates than there

are black voters who vote for white candidates. (T. 85) A

large segment of white voters will not vote for any black

candidate but few black voters will not vote for some white

candidates. (T. f 44 )

99. The result of the racially polarized voting is that for

black candidates to win, black voters must vote almost exclusively

for black candidates, thus forfeiting the right to vote for

a full slate of candidates. (Grofman T. 85, Hofeller T.

L437 )

100. Defendantsr expert, DE. Ilofeller, disputes Dr.Grofmanrs

conclusion that the racially polarized voting is substantive-

ly significant because Dr. Grofman did not analyze the totality

of the circumstances to determine whether race was the predominant

factor in determining election outcome. (T. 1452) Dr. Hofeller

did not perform this type of analysis himself. (T. 1454-5)

Nor did he testify that this type of analysis has been required

in any vote dilution litigation or appears anywhere in the

political science literature. (T. 1452) Moreov€E7 Dr. Hofeller

eoncedes that analysis he did do showed that race was a factor

in a number of elections (T. 1460). Dr. Hofeller further

concedes that the standard methodology to determine racially

polarized voting is to look at correlations. (T. 1445 ) In

addition, Dr. Hofeller has no previous experience in analyzing

31

racially polarized voting and no prior experience in nulti-member

districts. (Tr. 1458-60) Based on Dr. Grofmanrs extensive

experienee and the fact that the methods he used are the standard

methods in political science literature, the Court rejects

Dr. Ilofellerrs argument.

101. Based on the facts in paragraphs 80-100 of these

findings the Court finds thaE there is severe and persistent

racially polarized voting in elections for thd General Assembly

in each of the multi-member distriets in question (T. 81, 86),

and that this polarization contributes to'the inequality of

the opportunity of the black electorate to elect candiates of

its choice.

1.02. This assessment is supPorted.by the analysis of Dr.

Theodore Arrington, a professor of Political Science at the

University of North Carolina at Charlotte, who was accepted

as an expert in North Carolina political camPagins, elections

and practices. (Tr. 787-9 ) Dr. Arrington compared the pro-

portion of the vote received by black candidates in the current

multi-member majority white districts with the proportion of the

vote received by that candidate in a hypothetical majority-black

single-member district. He nade this comparison of elections

in 1980 and 1982 for the [tecklenburg, Forsyth, Durham and

Wake House districts and for the Mecklenburg Senate district.

(T. 796-8; Pugh Ex. 6-20) Dr. Arrington found a large amount

of racial polarization in each election and a substant,ial

difference between the way white voters and black voters voted.

(T. 799 , 805 )

32-

House District #8: RaciaIlv Polarized Voting

103. The Court finds that the findings eontained in para-

graphs 80-101 above apply to House District *8. fn addition,

the Court makes the following findings concerning racially

polarized voting in House District #8:

104. In county-wide or district-wide elections from L975-

1982 in House District *8 and l{ilson, Edgecombe, and Nash

Counties, the following percentage of white and black voters

voted for the black eandidate (P1. Ex. 11, App. 3t Table 1,

PI. Ex. 18):

Primary General

White BIack White Blaek

Wilson Count

f9g2 Congress-lst Primary-Michaux

2nd Primary-ttlichaux

1976 County Commission-Jones

Edgeeombe Countv

1982 Congress-lst Primary-Michaux

2nd Primary-Michaux

1982 County Commission-Green

McClain

Thorne

Walker

Nash Count

1982 Congress-lst Primary

2nd Primary

L982 County Commission-Sumner

96

98

77

6

7

32

66

84

97

14

27

75

82

2

3

0

0

4

2

6

5

9

38

36

91

94

73

81

82

House District *8

1982 House-Carter

33

105. With one exception, over 90t of the white voters

have failed to vote for the black candidate in every primary

in each of these three counties. (P1. Ex. l, App. 3t Table

1) The one time that black Democratic candidates made it to

a general election, they failed to receive over 50t of the

white vote even though Edgecombe County is overwhelmingly

(89.7t) Dernocratic. (f 104, suprai Answer to fnterrogatory *1)

106. Dr. Grofman testified that racial polarization of

voting in House District *8 is so extreme that no black has

any chance of winning in the district as it is presently

constituted. (T. 103, 105) Dr. Eofeller agreed that ra-

cially polarized voting in House District *8 is substantive-

ly significant. (T. 1454)

l07. This obj.ective anal.ysis is consistent with the subjec-

tive assessment made by Fred Belfield, a long time political

activist in Edgecombe and Nash Counties who testified that

black citizens do not have an equal opportunity to elect

candidates of their choice from the current House District

*8 simply because blacks are so outnumbered. (T. 7521

108. The Court finds that racial polarization of voting

in House District fB is extreme and persistent and, itself

prevents black citizens from having an equal opportunity to

elect any candidate of their choice to the North Carolina

llouse of Representatives.

34

Mecklenburg & Cabarrus Counties

House District *35 e Senate District #22:

Raciallv Polarized Voting

109. The Court finds that the findings, made in paragraphs

80-102 regarding racially polarized voting in a1I counties

in question apply in Mecklenburg and Cabarrus Counties. fn

addition, the Court makes the following findings of fact specif-

icalIy with regard to Mecklenburg and Cabarrus Counties.

1 10. In elections in llouse District *35 (Mecklenburg County)

between 1978 and 1982, the following percentage of black and

white voters voted for the black candidates (PI. Ex. 11,

App. 3t Table 1; P1. Ex. 14):

Primary

White Black

General

White Black

28 881980 (Maxwell)

1982 (Berry)

1982 (Richardson)

22

50

39

7T

79

71

42

29

92

92

91

n/a

94

fn elections in Senate District *22 (ltecklenburg

and Cabarrus Counties) between 1978 and 1982, the following

percentage of white and black voters voted for the black

candidates (Pl. Ex. 11, App. 3t Table 1; Pl. Ex. 13):

1978 (Alexander) 47

1980 (Alexander/Motley) 23

1982 (PoIk) 32

Primary

[!Ihite Black

87

78

83

General

white Black

41

n/a

33

1 1 1. THe fact that candidate Berry received votes from

one half of the white voters in the primary does not negate the

conclusion that there is substantial racially polarized voting

in Mecklenburg County in primaries, since there were only seven

35

white candidates for eight positions in the primary and one black

candidate had to be elected. (p1. Ex. 11, App. 3, Table I ) Berry,

the incumbent chairman of the Board of Education member (stip.

123) ranked lst among black voters but 7th among whites. (pr.

Ex. 11, App. 3, Table 2)

112. The only other brack candidate who even approached

getting half of the white voters to vote for him was Fred

Arexander in the 1978 primary when he ran as an incumbent. At

that, Alexander ranked last among white voters in the primary

and wourd have been defeated if the election had been held

among whites. (p1. Ex. 11, App. 3, Tables I & 2i Stip. 97)

113. Approximately 60t of whites voted for neither Berry

nor Alexander in the general election.

114. Defendantsr witness, Malachi Green, a black resident

of Mecklenburg County, who does not speak for other black voters

and whose views are not generarly shared by other politically

active blacks (T. 1189-90, 1478)? acknowledged that white voters

cannot be expected to vote for a black candidate by testifying

that if two majority black single-member House districts were

drawn in Mecklenburg County, a black could not be elected in the

remainder because most of the brack voters would be in the

single-member district and the remainder would be dominated by

whites with interests antithetical to the interests of blacks.

(T. L2721

115. fn addition, Green acknowledged that race was a factor

in the defeat of candidates Maxwerl (T. rzTa). polk (T. l,27gl

and Richardson (T. l27g). These candidates were the crear

36

choices of the black community, see il10 supra' and even

defense witness Representative Louise Brennan agreed these were

all "highly qualified candidates." (T. 1195-96)

116. The racial polarization of voting in Mecklenburg County

is exacerbated by the difficulty black candidates have in

forging coalitions with white politicians, (Lynch, T. 441),

and in convincing whites that there is nothing to fear from

having blacks served in eleetive office. (Lynch T. 4421

717. The polarization of voting in Mecklenburg County

means that black candidates will most likely lose unless Repub-

licans do poorly. If a Republican candidate wins and Ehere is

a black candidate in the general election, it is consistently

the black Democrat, and not a white Democrat, who is beaten

by the Republican. Thusr black candidates will fare less

well in years with high Republican turnout than in years

with 1ow Republican turnout. (Grofman, T. 94)

118. One of the results of racially polarized voting in

Mecklenburg County is that black candidates who have run and

lost will not run again, in part because of the difficulty

of attracting white votes and of Projecting themselves in a way

that is acceptable to white voters. (Lynch, T. 443)

119. In addition to polarization of voting in Mecklenburg

County, financial contributions to political campaigns is

also polarized along racial lines. White candidates receive

2t of their contributions from blacks, black candiates receive

30t of their funds from whites (although 82t of the registered

voters are white (Stip. *57)). (Arrington' T. 791)

37

120. There is no evidence that the trend of racially

polarized voting in Mecklenburg County is decreasing. (Grofnan

T. 95)

121. The result is, according to defendantst witness

Green, that in the current Senate District *22, in the Democratic

primary, if there is a black candidate and a white candidate,

and all other things are equalr the white candidate has a better

. chance of being successful. (Green, T. L2791

122. Based on the findings in paragraphs 80-102 above, and

in 109-121 herein, the Court finds that racially polarized

voting in Mecklenburg and Cabarrus Counties is not only

statistically significant, but also substantial to the extent

that it continues materially to decrease the opportunity of

black voters to elect representatives of their choice to the

North Carolina House of Representatives or Senate.

Forsvth Countv: Raciallv Polarized Voting

123. The Court finds that the findings made in paragraphs

80-102 above with regard to racially polarized voting in all

counties apply in House District *39 and in Forsyth County in

general. In addition, the Court makes the following findings

specifically about Forsyth County and House District t39:

124. In House and Senate elections in Forsyth County from

1978-1982 the following percent of white and black voters

voted for the black candidates (P1. Ex. 11' APp. 3, Table 1;

Pl. Ex. 15):

38

Primary

white BIack

General

White Black

1978 House-Kennedy, H.

Norman

Ross

1980 House-Kennedy, A.

Norman

Sumter (Repub)

1980 Senate-Smal1

1982 House-Hauser

Kennedy, A.

28

8

L7

40

76

29

53

85

32

n/a

n/a

32

n/a

42

46

95

n/a

n/a

96

n/a

87

94

18 35

n/a n/a

n/a n/a

33 2s

L2

25

51

80

36 91

125. .According to this analysis, 60t of white voters have

voted for no black candidate in a primary, and no black candidate

has gotten more than 46t of the white voters to vote for himr/her

in the general election.

126. The success of Kennedy and Hauser in the 1982 House

election does not indicate the end of racially polarized

voting or that there was not substantial polarization of

voting in that election. White voters ranked Kennedy and

Hauser seventh and eighth, respectively, out of eight candi-

dates in the general election. fn contrast black voters

ranked them first and second respectively. (T. 89; Pl. Ex.

11, App. 3. Table 21. Instead the success of Kennedy and

Hauser in the primary is more attributable to the unusually

large number of white candidates (nine) and the lack of

39

Democratic incumbents. Their success in the general election

is attributable to the unusually low white turnout ( 20t less

than 1980) and usually large black turnout for a non-presidential

year (the same as 1980). (T. 90)

127. The analysis of Dr. Hofeller of the election of a

black candidate to the lilinston Salem City Council from a majority

white ward supports rather than detracts from Ehe conclusion

of substantially racially polarized voting in Forsyth County.

Eofeller, who made no attempt to determine if more blacks than

whites actually voted in that election, acknowledges that voting

was racially polarized in both the primary and the general.

Furthermore, there is an almost perfect correspondence between

the percent of registered voters in each precinct that is bl-ack

and the percent of votes the candidate received ranging from lt

of the votes in a precinct with It black registered voters

to 55t of the votes in a precinct with 58t black registered

voters. (T. l42l-23; Def. Ex. 54)

128. The testimony of defendants' witness, C.B. Hauser, a

black representative from Forsyth County, also supports Dr.

Grofmanrs conclusion that there is substantial racially polarized

voting in Forsyth County. Hauser acknowledges that most of his

support came from the black community (Eauser Dep. p. 3I-32);

that he received the endorsement of the black but not the white

newspapers (id, at 20li and that race is a factor which makes

the election of black candidates more difficult in Forsyth

County (id. at 40). llauser also testified that when white

40

Republicans run against black Democrats in Forsyth County, white

Democrats cross over and vote Republican and this happens to

black candidates more than to white candidates so that black

candidates are more 1ike1y to lose to a Republican. (Hauser

Dep. p. 31) This testimony is consistent with Grofmanrs conclu-

sion that because of racial polarized voting in Forsyth County,

black candidates will lose unless Republicans do unusually

poorly. (T. 86 )

129. Hauserrs testimony indicates that the racial polariza-

tion of financial contributions which Dr. Arrington observed

in Mecklenburg County also exists in Forsyth County as only 20t

($2r000 out of $10r000) of his campaign funds were contributed

by white individuals or majority white political action commit-

tees. (Hauser Dep. p. 17)

130. Examining the last three election years there is no

evidence of a trend of decreasing racially polarized voting

in Forsyth County. (Grofman T. 87)

131. The result of the racially polarized voting in Forsyth

County is that it is easier to elect a white candidate of the

same qualifications as a black candidate because there are more

white voters. (Hauser Dep. at p. 41 )

132. Based on the findings contained in paragraphs 80-102

and 123-131 above, the Court finds that there continues to

be substantial racially polarized votring in Forsyth County

which makes it materially more difficult for black candidates

41

to be elected and which decreases the ability of black voters

to elect candidates of their choice to the North Carolina

House of Representatives.

Durham Countv - Racially Polarized Voting

133. The Court finds that the findings made in paragraphs

80-lilZ *itn regard to racially polarized voting apply in

Durham County. fn addition the Court makes the following

findings specifically about Durham County.

134. fn House and Senate elections in from 1978 through

L982, the following percentages of white and black voters

voted for black candidates (P1. Ex. 15, PI. Ex. 11, App. 3,

Table 1):

1978 House-Clement 10

Spaulding 16

1980 House-Spaulding n/a

1982 llouse-Clement 26

Spaulding 37

1982 Senate-Barns (Repub. I n/a

Primary

White Black

89

92

n/a

32

90

n/a

General

White BLack

n/a

37

49

n/a

n/a

89

90

n/a

43 89

L7 05

135. The black candidate ran uncontested in the general

election in 1978 and in the primary and general election in 1980.

In the 1982 election there was no Republican opposition and the

general election was, for practical purposes, unopposed. A

majority of white voters failed to vote for the black candidate

in the general election in each of these years even when they

had no other choice. Furthermore, in the 1982 primary, there

were two white candidates for three seats sor necessarily, one

42

black candiate had to win. Even in this situation, 63t of

white voters did not vote for the black incumbent, the clear

choice of the black voters. At least 37t of white voters

voted for no black eandidate even when one was certain to

be elected. fn this situation, white voters who would not

normally vote for a black candidate will vote for a black

candidate in order to exercise a choice about which black

candidate will be elected. The results of the 1982 election

signify extreme racial polarization of voting. (Grofman T.

99-102 )

136. The apparent error in the noted estimate of turnout in

plaintiffrs exhibit 16(e) (House general election 1982) or

plaintiffrs exhibit 15(f) (Senate general election 1982) does

not affect Dr. Grofmants assessment that there is substantively

significant racially polarized voting in Durham. (Grofman

T. 1473)

137. In Durham County the percent of Republican voters is

so low that winning the DemocraEic primary is tantamount to

election. (T.98-99)

138. Given the 1eveI of polarization in the Democrat,ic

primaries, if the incumbent does not run for re-election it will

be problematic for a non-incumbent black candidate to win

the primary. (T. 99 )

139. Dr. Grofmanrs analysis of Durham County elections

eomports with Durham resident Willie Lovettrs assessment that

large numbers of white voters will not, vote for black candidates

43

(T. 564-5). This is not contradicted by the testimony of Howard

Clement who reports that in 1978 and 1982 he got white financial

support and support from white workers (T. 1294-95) since

Clement received only 10t of the white vote in 1978 and 26t in

1982. Furthermorer Clement only got 32t of the black vote in 1982

and is clearly not the choice of the black community.

140. The level of racially polarized voting in primary

elections in Durham County is such that it materially decreases

the ability of black voters to elect representatives of their

choice.

Wake Countv - Polarization

141. The Court finds that the findings. in paragraphs

80-102 above with regard to racial polarization of voting

apply in $Iake County. In addition, the Court makes the following

findings specifically about Wake County.

142. In elections for the North Carolina House of Represen-

tatives from 1978 through 1982 the following percentage of white

and black voters voted for the black candidate. (P1. Ex. 11,

App. 3, Table I; Pl. Ex. 17):

Primary General.

White Black White Black

1978 Blue 2L 76 n/a n/a

1980 - BIue 31 81 44 90

t982 - Blue 39 82 45 91

44

145. In a county in which winning the Democratic primary

is tantamount to election (T. 102), from 60t to 80t of white

voters did not vote for the black candidate in the primary

compared to between 76t and 82$ of black voters who did.

(T. 103 )

146. fn a county whieh is overwhelmingly Democratic in

registration (77.6*; Answer to Interrogatory *1) and in which

normally vote along party lines (T. 582'), nonetheless 55t of

white voters did not vote for the black Democrat in the general

election.

147. The racial polarization of voting in the 1978 and 1980

elections, in which Blue was not an incumbent, was substantively

signifieant in that the the results wouLd have been different if

the election had been held only among white voters or only among

black voters. (T. 195, 212-214')

148. The polarization of voting in elections for the House

of Representatives in Wake County overall is substantively

significant and is such that while the chances of re-election of

the incumbent are good, it would be problematic for a different

black candidate to win should the incumbent retire. This is

because of the high percentage of white voters (69.7t on the

average) who do not vote for black candidates in primaries.

(Grofman, T. L02, 212-214)

149. Defendants counter the evidence of polarized voting in

Wake County by analyzing the election of a black incumbent (Baker)

as Sheriff in 1982. (Def . Ex. 53i T. 14-17) This election was

45

not, picked for analysis in an objective manner but was picked by

the attorney for defendants because it was an election in which

a black candidate won in a majority white district. (T. 1420)

Nonetheless, Hofeller concedes that even this analysis shows

statistically significant racially polarized voting. (T. 1425)

150. Eofeller did not analyze the results of the 1978

election when Baker initially ran. (T. 1423) In that election,

Baker received only 50.8t of the votes in the general election

(Stip. 157), suggesting that a large number of white Democrats

crossed over and voted for Bakerrs white Republican opponent.

(Spearman, T. 581-582)

151. Nothing in the analysis of the Baker elections contra-

dicts Dr. Grofmanrs assessment that the racial polarization of

voting in Wake County makes it problenatic for black non-incum-

bents to be elected.