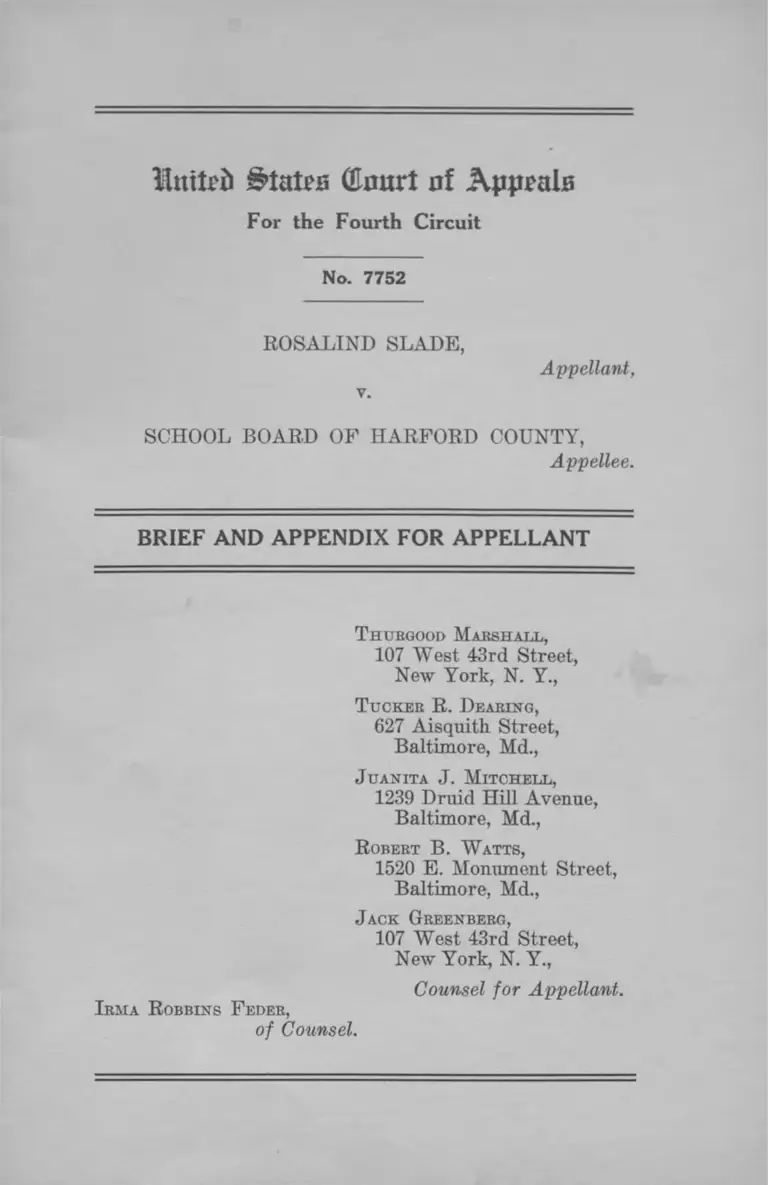

Slade v Harford County BOE Brief and Appendix for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

62 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Slade v Harford County BOE Brief and Appendix for Appellant, 1957. 4bb406a9-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b37b846-6227-4277-9e60-582125cd5857/slade-v-harford-county-boe-brief-and-appendix-for-appellant. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

Hutted States (Hourt of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

No. 7752

ROSALIND SLADE,

Appellant,

v.

SCHOOL BOARD OF HARFORD COUNTY,

Appellee.

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR APPELLANT

T hurgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, N. Y.,

T ucker R. D earing,

627 Aisquith. Street,

Baltimore, Md.,

Juanita J. M itchell,

1239 Druid Hill Avenue,

Baltimore, Md.,

R obert B. W atts,

1520 E. Monument Street,

Baltimore, Md.,

Jack Greenberg,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, N. Y.,

I rma R obbins F eder,

of Counsel.

Counsel for Appellant.

INDEX TO BRIEF

PAGE

Question Presented ......................................................

Statement ........................................................................

Argument .......................................................................

Table of Cases

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (C. A. 8th 1957) ..

Booker v. Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d

689 (6th Cir., 1957) ................................................

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 ..............

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F.

2d 853 (6th Cir., 1956), cert, denied 350 U. S.

1006 ..............................................................................

Dunn v. Board of Education of Greenbrier, 1 R. Rol.

L. Rep. 319 (S. D. W. Va. 1956) .............................

Garnett v. Oakley, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 303 (W. D. Ky.,

1957) ............................................................................

Gordon v. Collins, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 304 (W. D., Ky.,

1957) ............................................................................

Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir., 1956),

cert, denied 352 U. S. 925 .........................................

Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nash

ville, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 21 (M. D. Tenn., 1957)___

Mitchell v. Pollock, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 305 (W. D. Ky.,

1957) ............................................................................

Pierce v. Board of Education of Cabell County

(S. D. W. Va, 1956, unreported) .........................

School Board of the City of Charlottesville v. Allen,

240 F. 2d 59 (4th Cir., 1957), cert, denied 353 U. S.

910 ................................................................................

1

2

9

11

11

9

11

10

11

11

v

13

12

11

10

9

11

PAGE

School Board of the City of Newport News v. Adkins,

246 F. 2d 325 (C. A. 4th, 1957), cert, denied

— U. S. — ................................................................ 9

Shedd v. Board of Education of County of Logan,

1 R. Eel. L. Rep. 521 (S. D. W. Va. 1956).............. 10

Taylor v. Board of Education of County of Raleigh,

1 R. Rel. L. Rep. 321 (S. D. W. Va. 1956) .......... 10

Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 177 (W. D. Ky., 1955) 10

Other Authority

Black, Paths to Desegregation, New Republic, Octo

ber 21, 1957 ................................................................ 13

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Judgment ........................................................................ la

Opinion of November 23, 1956 ......................................... 4a

Opinion of June 20, 1957 ................................................ 16a

Excerpts from Testimony .............................................. 26a

Charles W. Willis:

Direct ............................................................ 26a, 36a

David G. Harry:

Cross ................................................................... 35a

Excerpts from Plaintiff’s Exhibit 1-a ......................... 40a

Question Presented

Whether appellants were denied rights secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment when the court below permitted

appellees’ school system to defer desegregation of certain

schools and grades for one to three years and prolong high

school desegregation until 1963 on a “ stair step” basis

(except for Negro students who might be admitted imme

diately upon passage of special examinations) where appel

lees did not sustain the burden of demonstrating the neces

sity for such delay?

o

Statement

This cause commenced with an earlier (separate) action.

See 146 F. Supp. 91, brought on behalf of some of the

appellants here to desegregate the schools in Harford

County. Two days before that cause came to trial appellees

adopted a resolution stating that

“ any child regardless of race may make individual

application to the Board of Education to be admitted

to a school other than the one attended by such child,

and the admissions to be granted by the Board of

Education in accordance with such rules and regula

tions as it may adopt and in accordance with the

available facilities in such schools, effective for the

school year beginning September, 1956.” 146 F.

Supp. at p. 93.

Counsel for the Board asserted that “ Since that plan

embraces the relief prayed for, I think that takes care of

that . . . ” Id. at p. 94. Relying on the Resolution, appel

lants agreed to dismiss the action, and believed the con

troversy concluded. Ibid. (The court concurred in their

interpretation and later, in a fresh suit (the instant one)

to require desegregation of the county’s schools, wrote that

“ plaintiffs were justified in believing, as I did, that appli

cations for transfer would be considered without regard

to the race of the applicant.” 152 F. Supp. at p. 119. The

Court therefore held appellees estopped to prevent admis

sion without regard to race of individual named plaintiffs

in the first suit. Id. at 119-120. The estoppel phase of the

suit is not at issue here and is set forth as background.)

On June 6, 1956 the Board announced its “ Transfer

Policy.” It reserved “ the right during the period of

transition to delay or deny the admission of a pupil to any

school, if it deems such action wise and necessary for any

good and sufficient reason.” 146 F. Supp. at p. 94.

On August 1,1956 it adopted a “ Desegregation Policy.”

Citing studies which allegedly indicated “ lowering of

3

school standards” upon desegregation and experience of

other areas with “ bitter local opposition” which prevents

“ orderly transition . . . and also adversely affects the

whole educational program.” 146 F. Supp at p. 95, the

Board announced that it would only permit Negro appli

cants for transfer to attend the first three grades of two

elementary schools in the county. Id. at p. 95. The reason

for selection of these schools was that they were, with

some slight exception, allegedly “ the only elementary

buildings in which space is available for additional pupils

at the present time.” The Board relied, too, on “ [s]ocial

problems posed by the desegregation of schools. . . . ” These,

it opined “ can be solved with the least emotionalism when

younger children are involved. The future rate of expan

sion of this program,” it concluded “ depends upon the

success of these initial steps.” Ibid.

Altogether sixty Negro children had applied for trans

fer under the impression that no racial distinctions were

to be made. There were, at the time, about 1,400 Negro and

12,600 white children in the school population. Of the

sixty applicants fifteen were admitted and forty-five re

jected pursuant to the “ Desegregation Policy” (App. pp.

26a-27a).

Appellants, therefore, on August 28, 1956, filed a fresh

suit alleging that defendants were under constitutional

duty to desegregate completely and that they were estopped

from retreating from their original resolution. (The Court

found an estoppel as to named plaintiffs, but held that the

County policy, generally, could not be fixed by estoppel.

Applicants here urge only their constitutional position.)

The trial court remitted appellants to an administrative

remedy before the State Board of Education.

The appellants (including intervenors who were granted

leave to intervene, 152 F. Supp. at p. 115) filed an appeal

with the State Board. While it was pending appellees

4

changed their policy once more on February 6, 1957. The

new policy provided that:

Applications for transfer will be accepted from

pupils who wish to attend elementary schools in the

areas where they live, if space is available in such

schools. Space will be considered available in schools

that were not more than 10% overcrowded as of

February 1, 1957. All capacities are based on the

state and national standard of thirty pupils per

classroom. 152 F. Supp. at p. 116.

Under the then newest plain five elementary schools

and the sixth grade in two schools were opened. Ibid.

The State Board held that the plan had been adopted in

good faith and constituted a reasonable start. Ibid.

At a hearing of this cause on April 18, 1957 the plan of

February 6 was amplified to include ten elementary schools

and the .sixth grade in one school; as well as three elemen

tary schools as of September 1958, when contemplated con

struction was projected to be completed. Three elementary

schools and the sixth grade of a high school would commence

receiving Negroes’ applications in September 1959.

As a normal result of the plan, the Board observed,

sixth grade graduates would have been ‘ ‘ admitted to junior

high schools for the first time in September, 1958 and

would proceed through high schools in the next higher

grade each year. This will completely desegregate all

schools of Harford County by September, 1963.” 152 F.

Supp. at p. 117.

At the April, 1957 hearing, the Court ruled tentatively

that the plan was “ generally satisfactory for the elemen

tary grades but not for the high school grades.” Ibid.

Another hearing was scheduled for June 11, 1957. On

June 5th, the Board changed its plan once more and noti

fied the parties of the change just before the hearing.

(App. p. 39a). The new plan—consisting of additions to

5

the old would permit Negro children to' enter high school

by a route additional to that of the earlier plan (whereby

they could enter only through normal promotions from

desegregated elementary schools). It would permit Negro

children to take .special examinations and be specially

evaluated for admission to nonsegregated high schools,

152 F . Supp. at 117; white children, and Negro children

entering via the high school plan designed to evolve during

1958-1963, would not be required to take these tests. Under

the revised plan complete desegregation of the seventh

grade, however, was still deferred until September, 1958.

152 F. Supp. at 119.

The reason given for the scheme of desegregating the

high schools over a period of four years in conjunction

with the right of .specially qualified Negro applicants to

enter starting immediately, as summarized by the Court,

was:

. . . when a child transfers to a high school from

another high school he faces certain problems which

do not arise when he enters the seventh grade, which

is the lowest grade in the Harford County high

schools. After a year or so in the high schools so

cial groups, athletic groups and subject-interest

groups have begun to crystallize, friendships and at

tachments have been made, cliques have begun to

develop. A child transferring to the school from

another high school does not have the support of a

group which whom he has passed through elementary

school. A Negro child transferring to an upper grade

at this time would not have the benefit of older

brothers, sisters or cousins already in the school, or

parents, relatives or friends who have been active

in the P. T. A. High school teachers generally, with

notable exceptions, are less ‘ pupil conscious’ and

more ‘ subject conscious’ than teachers trained for

elementary grades, and because each teacher has

the class for only one or two subjects, are less likely

to help in the readjustment. 152 F. Supp. at p. 118.

The pertinent parts of the plan of the school board,

viewed as a whole, as of the last hearing, and as embodied

G

in the Court’s order from which plaintiffs appeal, are now

as follows:

1. Defendants now and hereafter shall accept

applications for admission or transfer to all ele

mentary classes under their control (except in the

schools named in paragraph 2 as to which applica

tions will be accepted as described in that para

graph), in accordance with rules and regulations set

forth in paragraph 3 and every Negro child’s ap

plication to classes governed by the instant para

graph shall be considered and granted on the basis

upon which it would be considered and granted if

he were white.

2. Defendants shall accept Negro children’s ap

plications for admission or transfer to Old Post Road,

Bel Air and Highland elementary schools for the

school year 1958-1959 and thereafter; and shall ac

cept Negro children’s applications for admission or

transfer to Forest Hill, Jarrettsville and Dublin ele

mentary schools and the sixth grade at Edgewood

High School for the school year 1959-1960 and there

after. Every Negro child’s application to the schools

named in this paragraph for the respective school

years specified herein and thereafter shall be con

sidered and granted on the basis upon which it would

be considered and granted if he were white.

3. All applications for transfer to elementary

classes shall be made during the month of May on a

regular application form furnished by the Board of

Education and must be approved by the applicant’s

classroom teacher and the principal of the school the

applicant attends. Such applications will be re

viewed at the regular June meeting of the Board of

Education. Applicants and their parents will be in

formed of the action taken on applications prior to

the close of school in June of each year. In no event

shall a Negro child’s application for admission or

transfer be rejected if it would have been granted

had he been white.

4. A Negro child’s application for admission or

transfer to seventh grade classes commencing Sep-

7

tember, 1958, and thereafter, under defendant’s con

trol shall be considered and granted on the basis upon

which it would be considered and granted if he were

white. Such applications to the following classes

shall be so treated during and after the year set forth

alongside the class, as follows:

eighth grade — 1959

ninth grade — 1960

tenth grade — 1961

eleventh grade — 1962

twelfth grade — 1963

In 1963 and therafter all Negro applicants to all

classes shall be admitted on the same basis upon

vilich they would be admitted if they were white.

5. Commencing September, 1957 applications for

admission or transfer by Negro children not qualified

for admission or transfer under paragraph 4 to high

schools under defendants’ control will be considered

and granted if the applicants fulfill special qualifica

tions pertaining to the probability of success of each

individual pupil. These qualifications will be mea

sured by_ intelligence and achievement tests, grade

level achievements and other similar matters to be

adjudged by a committee consisting of the principals

of the schools from which the pupil is transferring

and the school to which he desires to transfer, the

Diiectoi of Instruction and the county supervisors

working in these schools. Apart from the fact that

these conditions may be applied only to Negro stu

dents not qualified for admission under paragraph 4

no i acial distinction is to be made in the administra

tion of these tests and evaluations. Such applications

may be made to the Board of Education between July

1 and July 14 of 1957 and years following in which

these tests may be given.

» * *

7. No racial distinctions whatsoever shall be

made by defendants in treating Negro children who

have been admitted to schools pursuant to this decree

(App. la-3a)

* * *

8

The record reveals that problems of overcrowding,

pupil adjustment, etc., would not stand in the way of free

transfer for white children who had never attended the

Harford County schools before and who moved into the

county:

“ Q. (By Mr. Greenberg) If white persons moved

from Delaware or Virginia or elsewhere, moved into

Harford County, that is at the present time, such

as to work in an industrial plant, would their children

be admitted to the schools at the present time?

A. (By Mr. Willis, Superintendent of Schools)

Yes, sir, they would.” (App. p. 29a)

See also App. 28a.

Moreover, whatever may be said of overcrowding it

was not so severe that the Subcommittee on Facilities of

appellees’ Citizens Consultant Committee on Integration

could not conclude: “ the committee is of the opinion that

provision can be made to accommodate such colored

students as apply for admission to Harford County public

schools for the year 1956-57.” (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1-a,

App. p. 44a)

The record further shows that deferring desegregation

of the seventh grade is without even purported justifica

tion:

“ The Court: Why can’t you admit a child to

the seventh grade in 1957?

“ The Witness: (Mr. Willis) I can’t say why,

your Honor, but the policy was moving forward

three years, and that was all.” (App. pp. 35a-36a)

* # #

“ The Court: It is a policy reason and there is

no administrative reason why you say the seventh

grade in 1958 and not the eighth grade also, that it

is only policy reasons.

‘ The Witness (Mr. W illis): The only extension

of the policy that has been accepted for the reasons

that have been given.

“ The Court: And no administrative reasons?

“ The Witness: Well, I won’t say none, but at

the moment I don’t think of any big one, let’s put it

that way.” (App. pp. 36a-37a)'

9

The Board’s plans were based not only on the alleged

considerations set forth above, but on apprehension that

proceeding otherwise might provoke public demonstrations

or opposition like some which occurred in Delaware and

elsewhere. (App. pp. 30a, 37a, see 146 F. Supp. at p. 95.)

Argument

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 sets forth

the only standards concerning what constitutes “ deliberate

speed” : (a) “ plaintiffs’ . . . admission to public schools

as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis ’ ’ ; and

(b) that “ [t]he burden rests upon the defendant to estab

lish that such [additional] time is necessary in the public

interest and is consistent with good faith compliance at

the earliest practicable date.” 349 U. S. at p. 300. While

the need to solve administrative problems may be occasion

for delay, and plans in the first instance are to be formulated

by school boards, “ the vitality of these constitutional

principles cannot be allowed to yield simply because of

disagreement with them.” Ibid.

The second Broivn opinion has been considered by

District Courts and Courts of Appeals on a number of

occasions. In this Circuit, district courts have ordered

complete desegregation by the next school year or term

in Charlottesville,1 2 Arlington,- Newport News 3 and Nor

folk,4 where local school officials had taken no steps what

ever towards desegregation, and, this Court has affirmed.

Moreover, in a series of West Virginia District Court cases

in this Circuit involving plans, overcrowding, fiscal prob

lems, and time for consideration, have been rejected as

grounds for delay when it was clear that Negro children

1 School Board of the City o f Charlottesville v. Allen, 240 F. 2d

59 (4th Cir., 1957); cert. den. 353 U. S. 910.

2 Ibid.

3 School Board o f the City o f Newport News v. Adkins, 246

F. 2d 325 (C. A. 4th, 1957) ; cert. den. — U. S. —.

4 Ibid.

10

could be admitted notwithstanding the preferred reasons

for deferment. Shedd v. Board of Education of County

of Logan, 1 R. Eel. L. Rep. 521 (S. D. W. Va. 1956); Dunn

v. Board of Education of Greenbrier, 1 R. Rel. L. Rep. 319

(S. D. W. Va. 1956); Taylor v. Board of Education of

County of Raleigh, 1 Rel. L. Rep. 321 (S. D. W. Va. 1956);

Pierce v. Board of Education of Cabell County (S. D.

W. Va. 1956, unreported). These cases have treated over

crowding not as a racial problem but as a spatial one.

I f there were to be a shortage of space, admissions could

be conditioned on room being available— but not on a

racial basis as appellees have done.

(Of course, such decisions did not outlaw the application

of normal transfer criteria. But, in this case, the Negro

children barred by the Harford plan may not use normal

transfer procedure.)

Other jurisdictions which have reviewed plans divide

into two principal categories: on the one hand, cases in

volving plans of districts in Kentucky, Ohio and the state

colleges of Tennessee; on the other, plans.involving schools

in Arkansas and Nashville. The first group of cases has

uniformly rejected delay based upon overcrowding, fiscal

problems, transportation difficulties and other administra

tive considerations where it could not be shown that these

actually were a bar to admitting Negro applicants.

In other words, the courts held that it was not enough

that problems existed; they could not defer desegregation

unless the burden of showing why time was required could

be met. In Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 177 (W. D. Ky.,

1955) the court pointed out that “ no white children either

before or after the application for admission of the plain

tiffs, were denied admission” and that “ good faith alone

is not the test. There must be ‘ compliance at the earliest

11

practicable date. ’ ” 136 F. Supp. at p. 181. Desegregation

was ordered by the next school year.5

Moreover in Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro,

228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir., 1956) cert, denied 350 U. S. 1006,

the Court of Appeals held that where as here, white chil

dren were not rejected during alleged overcrowding de

segregation could not be delayed for that reason. See also

Booker v. Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d 689

(6th Cir., 1957) cert. den. 1 L. Ed. 2d 915 reaffirming that

race may not be used as a standard to deal with crowded

conditions.

The second group of cases has approved plans running

into perhaps six years on the basis of a recital of problems

in school administration. But there has been no effort by

appellees in the instant case to catalogue in detail as prob

lems in Harford Comity the list of avowed reasons for delay

proffered in Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (C. A. 8th,

1957) one of the cases justifying delay:

Foremost among the problems of the Little Rock

School District are those of finances, structural or

ganization, enrollment, and the selection and train

ing of an adequate staff. These problems are not

new, but they will be greatly accentuated by integra

tion. By its plan the School Board is seeking to in

tegrate its schools and at the same time maintain or

improve the quality of education available at these

schools. Some of its objectives are to provide the

best possible education that is economically feasible,

to consider each child in the light of his individual

ability and achievement, to foster sound promotion

5 See also Gordon v. Collins, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 304 (W . D. Ky.

1957) (court rejecting alleged reasons for delay which included

overcrowding, transportation difficulties, reallocation problems, need

for time to study the problems, unfavorable social conditions; the

position of defendants is unreported) ; Mitchell v. Pollock, 2 R. Rel.

L. Rep. 305 (W . D. Ky., 1957) (rejecting similar grounds for de

lay) ; and see, for the same considerations and holding Garnett v.

Oakley, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 303 (W . D. Ky., 1957).

12

policies, to provide necessary flexibility in the school

curriculum from one attendance area to another, to

select, procure, and train an adequate school staff,

to provide necessary in-service training for the

school staff, to provide a necessary educational pro

gram for deviates (mentally retarded, physically

handicapped, speech correction, etc.), to provide the

opportunity for children to attend school in the at

tendance area where they reside, to foster sound ad

ministrative practices, to maintain extra-curricular

activities, to attempt to provide information neces

sary for public understanding, acceptance and sup

port, and to provide a “ teachable’ group of chil

dren for each teacher. With regard to the later ob

jective, it is the policy of the Board to group chil

dren with enough homogeneity for efficient planning

and classroom management. 143 F. Supp. at p.

860.6

Appellants submit that the alleged impedimenta prof-

ferred by appellees for delay herein have not only been

rejected in the largest number of cases where considerd by

the courts, but in those cases where reasons for delay have

been held sufficient the barriers have surpassed in com

plexity those advanced here.

The appellees are not in the dark as to how many Negro

applicants they may expect: about 60 in a school system

of 14,000 children; at least 15 of these already have been

admitted.

Their argument about overcrowding becomes meaning

less in view of this small number, when at the same time

they concede that comparable white children transferring

8 The Nashville ( Kelley v. Board o f Education of the City of

Nashville), 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 21 (M . D. Tenn. 1957) delay was found

to have been justified by “ numerous administrative problems, in

cluding increased difficulty in procuring and retaining teachers, teach

ing adjustments required because of differences in achievement

levels o f students among Negro and white children, problems arising

from a liberalized student transfer system supplanting a strict

transfer system, as well as other problems . . .”

13

from out of the jurisdiction will be admitted. As to de

ferring desegregation of the seventh grade they are at a

loss even to advance a reason. With respect to the high

schools they urge only that high school work is so alien

from earlier educational experience that Negroes must he

introduced a few at a time so that there will be others with

whom they can associate. But white children too meet novel

situations in high school, and it defies experience to deny

that Negro children will make friends with their white

classmates.

The chief administrative problem that appellees have

experienced has been the formulation and reformulation

of so many plans. The clear inference from the record

has been that the sole reason for delay has been reluctance

to admit Negro children, not difficulties recognized by the

Supreme Court’s decision. Indeed appellees have stated

on a number of occasions that they have put off desegrega

tion because of fear of opposition. But compare, Jackson

v. Rato don, 235 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1956), cert. den. 352

U. S. 925. While one may not view lightly the attitudinal

conflict that may accompany revision of school procedures

to comply with the Fourteenth Amendment, still the law

has recognized some and rejected other grounds for delay.

It does not recognize reluctance or social difficulties. More

over, as Professor Charles Black, probably the most per

ceptive commentator on the subject has demonstrated,

submitting to community opposition does not create the

acquiescence that purports to justify deferring or denying

the rights of rejected Negro children pending the delay.

Black, Paths to Desegregation, New Republic, October 21,

1957, p. 10.

W herefore it is respectfully submitted that the judg

ment below be reversed and appellees be required to cease

14

denying appellants their constitutional rights by the

beginning of the next school term.

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, N. Y.,

T ucker R. Dearing,

627 Aisquith Street,

Baltimore, Md.,

Juanita J. M itchell,

1239 Druid Hill Avenue,

Baltimore, Md.,

R obert B. AVatts,

1520 E. Monument Street,

Baltimore, Md.,

Jack Greenberg,

107 AVest 43rd Street,

New York, N. Y.,

Counsel for Appellant.

Irma R obbins F eder,

of Counsel.

la

APPENDIX

Judgment

This cause having come on for final hearing by the court

without a jury on June 11, 1957 and the court having heard

all the evidence adduced and being fully advised in the

premises, it is hereby ordered, adjudged and decreed as

follows:

1. Defendants now and hereafter shall accept applica

tions for admission or transfer to all elementary classes

under their control (except in the schools named in para

graph 2 as to which applications will be accepted as

described in that paragraph), in accordance with rules

and regulations set forth in paragraph 3 and every Negro

child’s application to classes governed by the instant para

graph shall be considered and granted on the basis upon

which it would be considered and granted if he were white.

2. Defendants shall accept Negro children’s applica

tions for admission or transfer to Old Post Road, Bel Air

and Highland elementary schools for the school year 1958-

1959 and thereafter; and shall accept Negro children’s

applications for admission or transfer to Forest Hill,

Jarrettsville and Dublin elementary schools and the sixth

grade at Edgewood High School for the school years 1959-

1960 and thereafter. Every Negro child’s application to

the schools named in this paragraph for the respective

school years specified herein and thereafter shall be con

sidered and granted on the basis upon which it would be

considered and granted if he were white.

3. All applications for transfer to elementary classes

shall be made during the month of May on a regular

application form furnished by the Board of Education and

must be approved by the applicant’s classroom teacher and

2a

Judgment

the principal of the school the applicant attends. Such

applications will be reviewed at the regular June meeting

of the Board of Education. Applicants and their parents

will be informed of the action taken on applications prior

to the close of school in June of each year. In no event

shall a Negro child’s application for admission or transfer

be rejected if it would have been granted had he been

white.

4. A Negro child’s application for admission or transfer

to seventh grade classes commencing September, 1958, and

thereafter, under defendant’s control shall be considered

and granted on the basis upon which it would be considered

and granted if he were white. Such applications to the

following classes shall be so treated during and after the

year set forth alongside the class, as follows:

eighth grade — 1959

ninth grade — 1960

tenth grade — 1961

eleventh grade — 1962

twelfth grade — 1963

In 1963 and thereafter all Negro applicants to all classes

shall be admitted on the same basis upon which they would

be admitted if they were white.

5. Commencing September, 1957 applications for admis

sion or transfer by Negro children not qualified for admis

sion or transfer under paragraph 4 to high schools under

defendants’ control will be considered and granted if the

applicants fulfill special qualifications pertaining to the

probability of success of each individual pupil. These

qualifications will be measured by intelligence and achieve

ment tests, grade level achievements and other similar

matters to be adjudged by a committee consisting of the

3a

Judgment

principals of the schools from which the pupil is transfer

ring and the school to which he desires to transfer, the

Director of Instruction and the county supervisors work

ing in these schools. Apart from the fact that these condi

tions may be applied only to Negro students not qualified

for admission under paragraph 4 no racial distinction is

to be made in the administration of these tests and evalua

tions. Such applications may be made to the Board of

Education between July 1 and July 15 of 1957 and years

following in which these tests may be given.

6. Infant plaintiff Moore shall be admitted to the

sixth grade at the Bel Air School. Infant plaintiff Spriggs

shall be admitted to the eighth grade at Edgewood High

School.

7. No racial distinctions whatsoever shall be made by

defendants in treating Negro children who have been

admitted to schools pursuant to this decree.

8. This Court retains jurisdiction for the purpose of

granting any other relief that may become necessary.

4a

T homskn, Chief Judge.

This action, brought by four Negro children seeking ad

mission to certain public schools in Harford County, Mary

land, present: (1) the usual questions under Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed.

873; Id., 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083; (2)

the same questions of law which were raised by the de

fendants in Robinson v. Board of Education, D. C. D. Md.,

143 F. Supp. 481; and (3) a problem of equitable estoppel

arising out of a previous action brought by the plaintiffs

herein and others against the defendants herein, which was

dismissed by the plaintiffs in reliance upon a resolution

adopted by the defendants, the Board of Education of Har

ford County.

F acts

Harford County is predominately rural, but in the

southern portion of the county there are two large govern

ment reservations, the Aberdeen Proving Ground at Aber

deen, and the Army Chemical Center at Edgewood. On

these reservations there are non-segregated housing de

velopments.

There are approximately 12,600 white students and 1,400

Negro students in the public schools of Harford County.

The defendant Board of Education operates a 6-3-3 sys

tem; that is, 6 years of elementary school, 3 years of jun

ior high and 3 years of senior high. The white high schools,

at Bel Air, Bush’s Comer (North Harford), Edgewood,

Aberdeen, and Havre de Grace, are combination junior-

senior high schools; the colored schools, at Hickory and

Havre de Grace, are “ consolidated schools” , comprising

elementary, junior high and senior high classes.

Opinion of November 23, 1956

5a

On June 30, 1955, just one month after the second opin

ion in Brown v. Board of Education, the Board of Educa

tion of Harford County selected a Citizens Consultant Com

mittee of thirty-six members from all sections of the county,

five of whom were Negroes, to consider the problem of

desegregation of the public schools in Harford Comity

and to make reconnnendations to the Board of Education.

On July 27, 1955, a group of Negro parents petitioned

the Board of Education, calling upon them “ to take imme

diate steps to reorganize the public schools under your

jurisdiction on a nondiscriminatory basis.”

The Citizens Consultant Committee held its first meet

ing on August 15, 1955, and was split up into a number of

sub-committees, to consider facilities, transportation and

. social relationships respectively. A member of the staff

of the Board of Education served as consultant to each sub

committee. The sub-committees met at various times dur

ing the rest of the year 1955 and the first two months of

1956.

On November 29, 1955, the four infant plaintiffs in the

instant case, together with seventeen other Negro children,

through their parents and next friends, brought suit in this

court against the defendants herein (Civil Action No. 8615),

alleging that the Board had “ refused to desegregate the

schools within its jurisdiction and has not devised a plan

for such desegregation,” and praying that:

“ 1. The court advance this cause on the docket

and order a speedy hearing of the application for

preliminary injunction and the application for per

manent injunction according to law and that upon

such hearings:

“ 2. The Court enter preliminary and permanent

judgments that any orders, customs, practices, and

usages pursuant to which said plaintiffs are segre

Opinion of November 23, 1956

6a

gated in tlieir schooling because of race, violate the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution.

“ 3. The Court issue preliminary injunctions or

dering the defendants to promptly present a plan

of desegregation to this Court which will expedi

tiously desegregate the schools in Harford County

and forever restrain and enjoin the defendants and

each of them from thereafter requiring these plain

tiffs and all other Negroes of public school age to

attend or not to attend public schools in Harford

County because of race.

“ The Court allow plaintiffs their costs and such

other relief as may appear to the Court to be just. ”

On February 27, 1956, the Citizens Consultant Commit

tee held a meeting, at which all of the sub-committees pre

sented their final reports, and the full committee unani

mously adopted the following resolution:

“ To recommend to the Board of Education for

Harford County that any child regardless of race

may make individual application to the Board of Ed

ucation to be admitted to a school other than the

one attended by such child, and the admissions to be

granted by the Board of Education in accordance

with such rules and regulations as it may adopt and

in accordance with the available facilities in such

schools; effective for the school year beginning Sep

tember, 1956.”

On March 7, 1956, the Board of Education of Harford

County adopted the resolution as submitted by the Citizens

Consultant Committee.

Opinion of November 23, 1956

Opinion of November 23, 1956

On March 9, 1956, Civil Action No. 8615 came on for

hearing before me on defendants’ motion to dismiss the

complaint, pursuant to Rule 12(b), Fed. Rules Civ. Proc.

28 U. S. C. A. At the beginning of the hearing, counsel for

defendants advised the court that the Board of Education

of Harford County had “ approved or adopted” the recom

mendation offered by the Citizens Consultant Committee

and read the resolution into the record. lie then said:

*1 Since that plan embraces the relief prayed for, I think

that takes care of that, and I want to call that to Your

Honor’s attention.” Counsel for plaintiffs then said:

“ We are in a position to enter into a consent decree em

bodying the terms of this resolution. We would like to

discuss it, but I do not think there is any need for further

litigation.” Counsel for the defendants replied: “ I do

not think that the Court should enter a consent decree when

the relief prayed for is the policy adopted by the Board.

I think the complaint should be dismissed in open court

because there is really nothing before the Court to effectu

ate.” I then left the bench so that counsel could discuss

the matter more freely. When court reconvened the fol

lowing colloquy took place:

“ Mr. Greenberg: We discussed this resolution

that has been adopted by the School Board and we

have told counsel for the defendants that we are sure

they are proceeding in good faith and this plan is

acceptable to us, and we will dismiss our suit and

make that a matter of record in open court, and file

this.

“ Mr. Barnes: That’s agreeable to the defend

ants, your Honor.

“ The Court: I think it would be well to have the

record show that in view of the fact that you have

been presented with this you olfered to dismiss the

suit, and attach this paper as an exhibit.

8a

“ Mr. Greenberg: Yes, sir.

“ The Court: I am very happy this has worked

out in a very satisfactory way.”

The following stipulation, signed by counsel for all par

ties, was filed in the case on the same day:

“ Dismissal of Action

“ 1. This cause came to be heard in this Court on

motion to dismiss the 9th day of March, 1956.

“ 2. Defendants, by their counsel, presented to

the Court the attached Resolution of the Harford

County Citizens Consultant Committee, adopted by

the Harford County Board of Education, as sub

mitted, at its regular meeting on March 7, 1956.

“ 3. Relying upon said resolution, as adopted,

plaintiffs hereby withdraw their complaint, and pray

that the same be dismissed, costs to be paid by

plaintiffs.”

To this stipulation was attached a certified copy of the

resolution recommended by the Citizens Consultant Com

mittee and adopted by the Harford County Board of Edu

cation.

On June 6,1956, the Board of Education adopted the fol

lowing “ Transfer Policy” , which all parties agree was

reasonable:

“ I f a child desires to attend a school other than

the one in which he is enrolled or registered, it will

be necessary for his parents to request a transfer.

Applications for transfer are available on request.

These requests should be addressed to the Board of

Education, c /o Superintendent of Schools, Bel Air,

Maryland. Applications will be received by the

Opinion of November 23,1956

9a

Board of Education between June 15 and July 15,

1956. All applications for transfer must state the

reason for the request, and must be approved by

the principal of the school which the pupil is now

attending.

“ Applications for transfer will be handled

through the usual and normal channels now operating

under the jurisdiction of the Board of Education and

its executive officer, the Superintendent of Schools.

“ While the Board has no intentions of compel

ling a pupil to attend a specific school or of denying

him the privilege of transferring to another school,

the Board reserves the right during the period of

transition to delay or deny the admission of a pupil

to any school, if it deems such action wise and neces

sary for any good and sufficient reason.

“ All applications for transfer, with recommenda

tions of the Superintendent of Schools, will be sub

mitted to the Board of Education for final considera

tion at the regular meeting of the Board on Wednes

day, August 1, 1956. When requests for transfer are

approved, parents must enroll their child at the

school on the regular summer registration date,

Friday, August 24, 1956.”

The transfer policy was advertised in all newspapers

published in Harford County. Sixty applications for trans

fer of Negro pupils were submitted within the time specified.

On August 1, 1956, the Board of Education of Harford

County adopted a “ Desegregation Policy” , embodied in a

document which recited the appointment of the Citizens

Consultant Committee, the recommendation made by that

Committee, the resolution adopted by the Board of Educa

tion on March 7, 1956, and the transfer policy adopted by

the Board in June. The statement of Desegregation Policy

continued as follows:

Opinion of November 23, 1956

10a

“ The Supreme Court decision, which required

desegregation of public schools, provided for an or

derly, gradual transition based on the solution of

varied local school problems. The resolution of the

Harford County Citizens Consultant Committee is

in accord with this principle. The report of this

committee leaves the establishment of policies based

on the assessing of local conditions of housing,

transportation, personnel, educational standards,

and social relationships to the discretion of the

Board of Education.

“ The first concern of the Board of Education

must always be that of providing the best possible

school system for all of the children of Harford

County. Several studies made in areas where com

plete desegregation has been practiced have indi

cated a lowering of school standards that is detri

mental to all children. Experience in other areas has

also shown that bitter local opposition to desegre

gation in a school system not only prevents an

orderly transition, but also adversely affects the

whole educational program.

“ With these factors in mind, the Harford County

Board of Education has adopted a policy for a

gradual, but orderly, program for desegregation of

the schools of Harford County. The Board has

approved applications for the transfer of Negro

pupils from colored to white schools in the first

three grades in the Edgewood Elementary School

and the Halls Cross Roads Elementary School.

Children living in these areas are already living in

integrated housing, and the adjustments will not

be so great as in the rural areas of the county where

such relationships do not exist. With the exception

of two small schools, these are the only elementary

buildings in which space is available for additional

pupils at the present time.

Opinion of November 23,1956

11a

“ Social problems posed by the desegregation of

schools must be given careful consideration. These

can be solved with the least emotionalism when

younger children are involved. The future rate of

expansion of this program depends upon the suc

cess of these initial steps.”

Pursuant to the Desegregation Policy so adopted,

fifteen of the sixty applications were granted, and forty-

five, including those of the infant plaintiffs in the instant

case, were refused. On August 7, 1956, the defendant

Charles W. Willis, Superintendent of Schools, sent the

following letter to the parents of each of the infant plain

tiffs :

“ The Board of Education, at its regular August

meeting, adopted a policy for the desegregation of

Harford County schools. Under the provisions of

this policy your child will not be allowed to transfer

from his present school. Your request for a trans

fer has been refused by the Board of Education.

“ A copy of the desegregation policy is enclosed.”

Neither the infant plaintiffs nor their parents appealed

to the State Board of Education from the action of the

County Superintendent denying their requests for transfer.

Nor have any appeals been filed by or on behalf of any of

the other Negro children whose requests for transfer were

refused.

On August 28, 1956, the four infant plaintiffs by their

parents and next friends filed the instant suit, pursuant to

Rule 23(a)(3), “ for themselves and on behalf of all other

Negroes similarly situated” , alleging most of the facts set

out above and other facts, some of which are disputed,

which need not be detailed at this time.

Infant plaintiff Moore seeks transfer from the Central

Consolidated Elementary School in Hickory to the elemen

Opinion of November 23,1956

12a

tary school in Bel Air, where he resides; Spriggs seeks

transfer from the school in Hickory to the High School

(junior high) in Edgewood, where he resides; Slade and

Garland seek transfer from the Havre de Grace Consoli

dated School to the Aberdeen High School (9th and 11th

grades respectively). They pray that:

“ 1. The Court advance this cause on the docket

and order a speedy hearing of the application for

preliminary injunction and application for perma

nent injunction according to law and that upon such

hearing;

‘ ‘ 2. The Court enter preliminary and permanent

judgments, that any orders, customs, practices and

usages pursuant to which said plaintiffs are each of

them, their lessees, agents and successors in office

from denying to plaintiffs and other Negro residents

of Harford County of the State of Maryland admis

sion to any Public School operated and maintained

by the Board of Education of Harford County, on

account of race and color.” (sic)

Defendants filed a motion to dismiss the complaint pur

suant to Rule 12(b), raising substantially the same points

which were considered in Robinson v. Board of Education

of St. Mary’s County, supra. I overruled that motion on

October 5, 1956. Defendants filed their answer on October

24, and the case was set for hearing on November 14. Both

sides offered testimony and documentary evidence. From

the testimony it appears that most, but not all, of the schools

in Harford County are overcrowded if the “ standards”

or “ goals” set out by the State are considered, namely, an

average of 30 per class in elementary schools and 25 per

class in secondary schools. But defendants conceded that

any white children moving into the county would be ad

mitted to the appropriate white school, however crowded.

Opinion of November 23,1956

13a

The factors considered by the Board of Education in adopt

ing the August 1 Desegregation Policy were discussed at

some length. The President of the Board of Education and

the County Superintendent testified that they did not con

sult counsel before adopting the August 1 Desegregation

Policy, but that they thought this policy was in accord

with the recommendation of the Citizens Consultant Com

mittee and with the March 7 resolution adopted by the

Board.

Plaintiffs ’ counsel do not charge bad faith against either

the Board or the Superintendent, but contend that:

“ I. The Harford County School Board Resolu

tion of March 7, 1956, meant that from the follow

ing school year and thereafter there would be no

legally compelled racial segregation of school chil

dren in Harford County;

‘ ‘ II. The defendants are estopped from any fur

ther delay in complete integration by their action in

causing plaintiffs to withdraw plaintiffs’ original

suit in reliance on the Board’s resolution, which

resolution was expressly incorporated by reference

into the court’s order of dismissal;

“ III. Plaintiffs are entitled to judicial rather

than administrative relief at this time in view of

the history and facts of this case;

“ A. Defendants, by their actions, are estopped

from asserting the doctrine of administrative ex

haustion as a defense;

“ B. Even if defendants were not estopped from

raising the defense of the doctrine of administrative

exhaustion, the defense would neverthelss fail as the

doctrine is not here applicable;

“ IV. Even if defendants could validly raise the

questions of necessary administrative delay, their

Opinion of November 23, 1956

14a

own actions clearly demonstrate the fact that no

additional time is needed to solve administrative

problems;

“ A. Defendants are administratively ready to

effectuate desegregation;

“ B. ‘ Community unreadiness’ constitutes no

legal justification for continued segregation.”

D iscussion

[1] The Maryland statutes and decisions were analyzed

in Robinson v. Board of Education of St. Mary’s County,

supra, 143 F. Supp. at pages 487-491. I adhere to that

analysis, and it need not be repeated here. It is clear that

some of the factors considered by defendants in the instant

case when they adopted the August 1 Desegregation Policy,

and some of the points argued by counsel for plaintiffs in

opposition thereto, involve administrative problems, over

which the State Board of Education has jurisdiction, and

which should be appealed to that Board under the Maryland

authorities. Some of the other factors and points involve

legal questions, which under Maryland law are for the

courts. Most, if not all, involve both administrative and

legal problems. Even the estoppel point is a mixed ques

tion, because the March 7 resolution leaves open at least

the question of available facilities, whatever other matters

may have been foreclosed.

Whether the court should attempt to segregate the legal

questions and decide them at this time, or should defer any

decision until the State Board has been given an oppor

tunity to pass on the problem as an integrated whole, is a

matter of comity and discretion. Since, at the time of the

hearing in the St. Mary’s County case, the State Board

assured the court that it will give prompt attention to any

Opinion of November 23,1956

15a

appeal filed by or on behalf of Negro students, I am satisfied

that I should not make a final decision in this case until

the plaintiffs have appealed to the State Board from the

action of the County Superintendent denying their applica

tions for transfer. Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S.

294, 75 S. Ct. 753; Hood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter

County School District No. 2, 4 Cir., 232 F. 2d 626; Carson

v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 4 Cir., 227 F.

2d 789; Robinson v. Board of Education of St. Mary’s

County, D. C. D. Md., 143 F. Supp. 481. However, the final

decision in this court, if one is necessary after the State

Board has acted, should be rendered within such time that

the losing parties may have an appeal heard by the Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit at its June, 1957 term.

Conclusions

[2] 1. The appointment of the Citizens Consultant

Committee in the summer of 1955, its study, resulting in

its recommendation to the Board of Education, and the

resolution adopted by the Board on March 7, 1956, were

a prompt and reasonable start toward compliance with

the Supreme Court ruling.

2. I intimate no opinion at this time with respect to

the sufficiency or propriety of the Desegregation Policy

adopted by the Board on August 1, 1956.

3. I will enter a decree dismissing this action unless

the plaintiffs appeal to the State Board of Education on

or before December 15, 1956, from the action of the County

Superintendent refusing their applications for transfer.

I f plaintiffs enter such an appeal, I will stay further pro

ceedings in this case until the State Board shall have

decided the appeal or shall have delayed decision for an

unreasonable time; provided that after the State Board

shall have rendered its decision, or after March 1, 1957,

whichever is earlier, either plaintiffs or defendants may

request the court to set this case for further argument

and prompt decision.

Opinion of November 23, 1956

16a

T homsen, Chief Judge.

This action was brought by four Negro children, on

their own behalf and on behalf of those similarly situated,

seeking admission to certain public schools in Harford

County, Maryland. The background and first stages of

the case are detailed in an opinion filed herein on Novem

ber 23, 1956, D. C., 146 F. Supp. 91.

Following that opinion, the four plaintiffs and eight

other children, who have asked and been granted leave

to intervene in this case, filed appeals with the State Board

o f Education from the refusal of the Superintendent of

Schools of Harford County to grant their applications for

transfer from consolidated schools for colored children to

various white schools which were not desegregated in Sep

tember, 1956.

While those appeals were pending before the State

Board, on February 6, 1957, the Harford County Board

adopted the following “ Extension of the Desegregation

Policy for 1957-1958” :

“ Applications for transfers will be accepted from

pupils who wish to attend elementary schools in the

areas where they live, if space is available in such

schools. Space will be considered available in

schools that were not more than 10% overcrowded

as of February 1, 1957. All capacities are based on

the state and national standard of thirty pupils

per classroom.

“ Under the above provision, applications will be

accepted for transfer to all elementary schools ex

cept Old Post Road, Forest Hill, Bel Air, Highland,

Jarrettsville, the sixth grade at the Edgewood High

School, and Dublin. Such applications must be

made during the month of May on a regular applica

tion form furnished by the Board of Education, and

Opinion of June 20, 1957

17a

must be approved by both the child’s classroom

teacher and the principal of the school the child is

now attending.

“ All applications will be reviewed at the regular

June meeting of the Board of Education and pupils

and their parents will be informed of the action

taken on their applications prior to the close of

school in June, 1957.”

After a hearing, the State Board dismissed the appeals,

finding that “ the Harford County Board acted within the

policy established by the State Board” , that “ the County

Superintendent acted in good faith within the authority set

forth in the August 1, 1956, Desegregation Policy adopted

by the County Board” ,1 that the Desegration Policy was

adopted in a bona fide effort to make a reasonable start

toward actual desegregation of the Harford County pub

lic schools” , and that “ this initial effort [the desegrega

tion of three grades in two elementary schools] has been

carried out without any untoward incidents” . The State

Board also took ‘ ‘ cognizance of the resolution of the County

Board of February 6, 1957” , set out above herein, “ as well

as the testimony to the effect that the proposed Harford

County Junior College, which is to be established in Bel Air

in the fall of 1957, will open on a desegregated basis, and

also the testimony to the effect that the present program

of new buildings and additions will make further desegre

gation possible” .

After the decision of the State Board, plaintiffs set this

case for further hearing, as provided in the earlier decree,

146 F. Supp. at page 98. That hearing was held on April

18, 1957. Charles W. Willis, the Harford County Super

intendent, explained and amplified the February 6, 1957

resolution of the County Board. The President of the

Opinion of June 20, 1957

1 See 146 F. Supp. at page 95.

18a

Board and its counsel accepted that interpretation. So

explained and amplified, the plan was substantially the

same as the plan which was later adopted by the County

Board on May 1, 1957, as follows:

“ The Board reviewed its desegregation policy

of February 6, 1957. In accordance with this plan,

the following elementary schools will be open in all

six grades to Negro pupils at the beginning of the

1957-1958 school year:

“ Emmorton Elementary School

“ Edgewood Elementary School

“ Aberdeen Elementary School

“ Halls Cross Roads Elementary School

“ Perryman Elementary School

“ Churchville Elementary School

“ Youth’s Benefit Elementary School

“ Slate Ridge Elementary School

“ Darlington Elementary School

“ Havre de Grace Elementary School

“ 6th Grade at Aberdeen High School

“ Schools now under construction or contem

plated for construction in 1958, if no unforeseen

delays occur, will automatically open all elementary

schools to Negro pupils by September, 1959. As a

result of new construction, the elementary schools

at Old Post Road, Bel Air, and Highland will accept

applications for transfer of Negro pupils for the

school year beginning in September, 1958. Forest

Hill, Jarrettsville, Dublin and the sixth grade at

the Edgewood High School would receive applica

tions for the school year beginning in September,

1959.

“ As a normal result of this plan, sixth grade

graduates will be admitted to junior high schools

for the first time in September, 1958 and will pro-

Opinion of June 20, 1957

19a

ceed through high schools in the next higher grade

each year. This will completely desegregate all

schools of Harford County by September, 1963.

“ The Board will continue to review this situation

monthly and may consider earlier admittance of

Negro pupils to the white high schools if such seems

feasible. The Board reaffirmed its support of this

plan as approved by the State Board of Education.”

At the April, 1957 hearing. I ruled tentatively that

the plan was generally satisfactory for the elementary

grades, but not for the high school grades, and suggested

that the parties attempt to agree on a modified plan. Con

ferences between counsel were held, but no agreement was

reached. The County Board, however, on June 5, 1957,

modified the plan as follows:

“ The Board reaffirmed its basic plan for the

desegregation of Harford County Schools, but agreed

to the following modification for consideration of

transfers to the high schools during the in terim

period while the plan is becoming fully effective.

“ Beginning in September, 1957, transfers will be

considered for admission to the high schools of Har

ford County. Any student wishing to transfer to a

school nearer his home must make application to the

Board of Education between July 1 and July 15.

Such application will be evaluated by a committee

consisting of the high school principals of the two

schools concerned, the Director of Instruction, and

the county supervisors working in these schools.

“ These applications will be approved or disap

proved on the basis of the probability of success and

adjustment of each individual pupil, and the commit-

tee will utilize the best professional measures of both

achievement and adjustment that can be obtained

in each individual situation. This will include, but

Opinion of June 20, 1957

20a

not be limited to, the results of both standardized

intelligence and achievement tests, with due con

sideration being given to grade level achievements,

both with respect to ability and with respect to the

grade into which transfer is being requested.

“ The Board of Education and its professional

staff will keep this problem under constant and con

tinuous observation and study.”

The modified plan was presented to the court at a hear

ing on June 11, 1957. It was made clear that when an

elementary school has been desegregated., all Negro chil

dren living in the area served by that school will have the

same right to attend the school that a white child living

in the same place would have, and the same option to attend

that school or the appropriate consolidated school that a

white child will have. The same rule will apply to the high

schools, all of which operate at both junior high and senior

high levels, as they become desegregated, grade by grade.

Of course, the County Board will have the right to make

reasonable regulations for the administration of its schools,

so long as the regulations do not discriminate against

anyone because of his race; the special provisions of the

June 5, 1957 resolution will apply only during the transition

period.

[1] Willis also testified that the applications which will

be made pursuant to the June 5, 1957 modification will be

approved or disapproved on the basis of educational fac

tors, for the best interests of the student, and not for other

reasons. I have confidence in the integrity, ability and

fairness of Superintendent Willis and of the principals,

supervisors and others who will make the decisions under

his direction. In the light of that confidence, I must decide

whether the modified plan meets the tests laid down in the

Opinion of June 20, 1957

21a

opinions of the Supreme Court and of the Fourth Circuit,2

with such guidance as may be derived from other decisions.3

The burden of proof is on defendants to show that a delay

during a transition period is necessary, that the reasons

for the delay are reasons which the court can accept under

the constitutional rule laid down by the Supreme Court, and

that the proposed plan is equitable under all the circum

stances. In considering whether defendants have met that

burden, the court must recognize that each county has a

different combination of administrative problems, tradi

tions and character. Many counties are predominantly

rural, others suburban; some have large industrial areas

or military reservations. See 146 F. Supp. at page 92.

[2] Eleven out of the eighteen elementary schools in

Harford County will be completely desegregated in Sep

tember, 1957, three months from now. Three more will be

completely desegregated in 1958, and the remaining four

in 1959. The reason for the delay in desegregating the

seven schools is that the county board and superintendent

believe that the problems which accompany desegregation

can best be solved in schools which are not overcrowded and

where the teachers are not handicapped by having too

many children in one class. That factor would not justify

unreasonable delay; but in the circumstances of this case

it justifies the one or two years delay in desegregating the

seven schools.

Opinion of June 20, 1957

2 Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753,

99 L. Ed. 1083; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74

S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873; Carson v. Warlick, 4 Cir., 238 F. 2d 724;

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 4 Cir., 227

F. 2d 789.

3 Aaron v. Cooper, D. C. E. D. Ark., 143 F. Supp. 855; Kelley

v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville, M. D. Tenn., 2 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 21 (1957). Cf Mitchell v. Pollock, W. D. Ky„ 2 Race

Rel. L. Rep 305 (1957).

22a

With respect to the high schools, other factors are

involved. Superintendent Willis testified that when a child

transfers to a high school from another high seiiool he

faces certain problems which do not arise when he enters

the seventh grade, which is the lowest grade in the Harford

County high schools. After a year or so in the high schools

social groups, athletic groups and subject-interest groups

have begun to crystallize, friendships and attachments have

been made, cliques have begun to develop. A child trans

ferring to the school from another high school does not have

the support of a group with whom he has passed through

elementary school. A Negro child transferring to an upper

grade at this time would not have the benefit of older

brothers, sisters or cousins already in the school, or parents,

relatives or friends who have been active in the P. T. A.

High school teachers generally, with notable exceptions,

are less “ pupil conscious” and more “ subject conscious”

than teachers trained for elementary grades, and because

each teacher has the class for only one or two subjects, are

less likely to help in the readjustment. The Harford County

Board had sound reasons for making the transition on a

year to year basis, so that most Negro children will have a

normal high school experience, entering in the seventh grade

and continuing through the same school. But I was un

willing in April to approve a plan which would prevent all

Negro children now in the sixth grade or above from ever

attending a desegregated high school.

However, the modified plan adopted on June 5, 1957,

permits any Negro child to apply next month for transfer

to a presently white high school, and if his application is

granted, to be admitted in September, 1957, three months

hence. This plan is different from any to which my atten

tion has been called or about which I have read. It is an

equitable way of handling the transition period. My only

doubt is whether it is necessary to postpone until September,

Opinion of June 20, 1957

23a

1958, the complete desegregation of the seventh grade. But

I am not charged with the responsibility of administering

the Harford County public school system. Although I

think the reasons given for the delay of one year are less

satisfactory than the reasons given for the rest of the

plan, a federal court should be slow to say that the line

must be drawn here and cannot reasonably be drawn there,

where the difference in time is short and individual rights

are reasonably protected, during the transition period,

as they are by the June 5, 1957 modification.

[3] Plaintiffs are obviously worried whether the June

5 plan will be carried out in good faith, or whether it will

be used as a means of postponing the admission of Negro

children into the high schools without proper justification.

Although, as I have said, I have confidence in Superin

tendent Willis and his staff, plaintiffs’ doubts are not un

reasonable in view of the past history of this litigation.

I will, therefore, enter a decree which will spell out the

rights of individual children under the plan, and will

retain jurisdiction of the case, so that if any child or his

parents feel that his application has been rejected for a

reason not authorized by the modified plan, a prompt hear

ing may be granted.

There remains the question of estoppel, based upon

the resolution adopted by the County Board on March

7, 1956, and the interpretation of that resolution by its

counsel in open court in the earlier Harford County case,

as a result of which the plaintiffs therein dismissed their

action. The facts on this point are set out fully in 146

F. Supp. 93 et seq.

[4] The March 7, 1956 resolution was somewhat

ambiguous, but, as it was interpreted by defendants’ coun

sel in open court, plaintiffs were justified in believing, as

I did, that applications for transfer would be considered

without regard to the race of the applicant. The County

Opinion of June 20, 1957

24a

Board interpreted it differently in the statement entitled

“ Desegregation Policy” adopted on August 1, 1956; see

146 F. Supp. at page 95. I cannot accept the interpreta

tion adopted by the County Board, but I fold that it was

adopted as a result of a mistake and not as the result of

any bad faith on the part of the Board, the Superintendent,

or their counsel. The Board adopted the Desegregation

Policy of August, 1956, in the honest belief that it was to

the best interests of all of the children in the County.

Pursuant to that policy the Superintendent admitted

fifteen Negro children to two previously white schools,

but denied admission to forty-five others, including the

infant plaintiffs herein.

There is grave doubt whether a governmental agency

such as a county school board can be estopped from adopt

ing a policy, otherwise legal, which it believes to be in the

best interests of all the people in the County. In the instant

case it would be inequitable and improper, on the ground

of estoppel, to require the County Board to open all schools

to Negroes immediately, as requested in the complaint.

The County Board should not be foreclosed by the facts

which I have found from taking.such actions, and adopt

ing and modifying such policies, as it believes to be in the

best interest of the people in the County, so long as those

actions and those policies are constitutional.

[5] The individual plaintiffs in the earlier case, how

ever, were prevented from pressing their individual rights

in this court and on appeal by the adoption of the March

7, 1956 resolution and by what took place in this court

in that case. See 146 F. Supp. 93 et seq. Two of those

infant plaintiffs are before the court in this case, and their

counsel urge that their individual rights, as well as any

class rights, be enforced. The reasons which prevent an

estoppel against the County Board so far as its general

Opinion of June 20, 1957

25a

Opinion of June 20, 1957

policies are concerned, do not apply with equal force to

the individual claims of those two children. It would not

be equitable to delay any further the enforcement of their

individual rights.

I will, therefore, include in the decree a provision

enjoining the County Board from refusing to admit Stephen

Moore and Dennis Spriggs to whatever school would be

appropriate for them if they were white.

26a

Excerpts from Testimony

* # *

Direct testimony of Charles W. W illis, Superintendent

of Schools.

[15 j Q. How many Negro children applied? A. We had

59 applications, and there was a mix-up on one that we

later admitted.

[16] Q. Well, approximately? A. That made 60.

Q. How many Negro children are there in the County

School System altogether? A. A little over 1400 at the

present time.

Q. How many white children are there in the County

School System? A. About 12,600, roughly ten percent Ne

gro children, about 14,000 children.

Q. That is 60 children of the total school population

out of how many ? A. 14,000.

Q. And how many Negro children were admitted? A.

Fifteen.

Q. Now, what was the reason for admitting fifteen and

rejecting the other forty-five? A. The main reason why

was we had facilities in the areas where the children were

admitted, and we had integrated housing in those areas,

and we felt that we would have less social adjustment prob

lems in the lower grades, and this was the beginning of

the plan of gradual integration, and we felt that that would

work in our System.

We had studied all we could find out about previous at

tempts and we had found out that trouble usually arose in