Senate hearing notes (Statements from Senators Hatch and Mathias)

Working File

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Senate hearing notes (Statements from Senators Hatch and Mathias), 1982. 6143fa65-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4bb78ee2-38aa-4f26-a1ad-3c8efba7be52/senate-hearing-notes-statements-from-senators-hatch-and-mathias. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

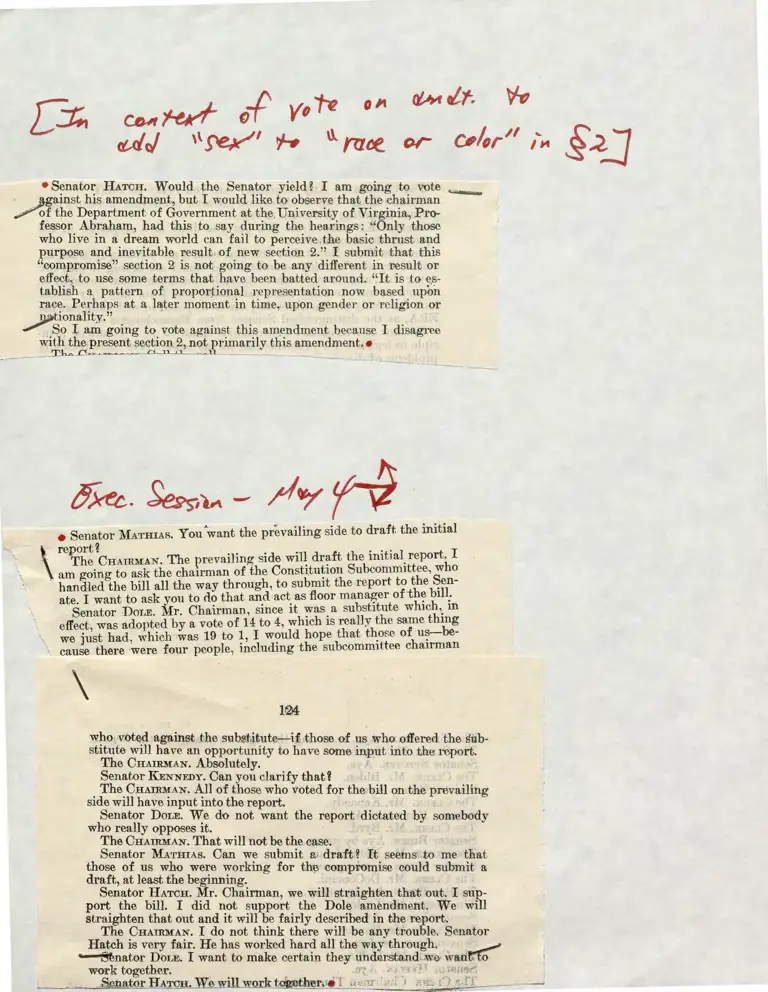

• Senator HATCH. Would the Senator yield~ I am going to vote

J}gainst his amendment, but I would like to observe that the chairman

/"of the Department of Government at the University of Virginia, Pro

fessor Abraham, had this to say during the hearings: "Only those

who live in a dream WQrld can fail to perceive the basic thrust and

purpose and inevitable result of new section 2." I submit that this

"compromise" section 2 is not going to be any different in result or

effect, to use some terms that have been batted around. "It is to e.s

tablish a pattern of proportional representation now based upon

race. Perhaps at a later moment in time, upon gender or religion or

WJ>tionality."

....,- So I am going to vote against this amendment because I disagree

with the present section 2, not primarily this amendment. •

____ T-~"--' o 1] •J .. :u --------~-~

\

\

\

tJ.xec. ~ .... - ~"1' ~

• Senator MATHIAS. You~want the prevailing side to draft, the initial

The CHAIRMAN. The prevailing side wil~ dr:;t t e m1 ,la. repor ·

\

report~ . ft h · •t· 1 t I

am going to ask the chairman of the Constltu~wn Subcommittee, who

handled the bill all the way through, to submit the report to the ~en

ate. I want to ask you to do that and act as floor manager of th~ bill;

Senator DoLE. Mr. Chairman, since it was a substitute which,. m

effect, was adopted by a vote of 14 to 4, which is really the same thmg

\ we just had, which was 19 to 1, I would hope that tl~ose of u~-be

cause there were four people, including the subcommittee chairman

\

who, voted against the substitute-if those of us who offered the sub

stitute will have an opportunity to have some input into the report.

The CHAIRMAN. Absolutely.

Senator KENNEDY. Can you clarify that~

The CHAIRMAN. All of those who voted for the bill on the prevailing

side will haveinput into the report.

Senator DoLE. We do not want the report dictated by somebody

who really opposes it.

The CHAIRMAN. That will not be the case.

Senator MATHIAS. Can we submit a draft~ It seems to me that

those of us who were working for the compromise could submit a

draft, at least the beginning.

Senator HATCH. Mr. Chairman, we will straighten that out. I sup

port the bill. I did not support the Dole amendment. We will

straighten that out and it will be fairly described in the report.

The CHAIRMAN. I do not think there will be any trouble. Senator

Hatch is very fair. He has worked hard all the way through. _ __.,;

~nator DoLE. I want to make certain they understand we wanrto

work together. '

Senator HATCH. We will work together. • ---