Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Senator Strom Thurmond

Correspondence

February 25, 1986

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Senator Strom Thurmond, 1986. ed53c54e-e992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/50b8f9f4-16fa-4c63-8055-f6f258adf1d4/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-senator-strom-thurmond. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

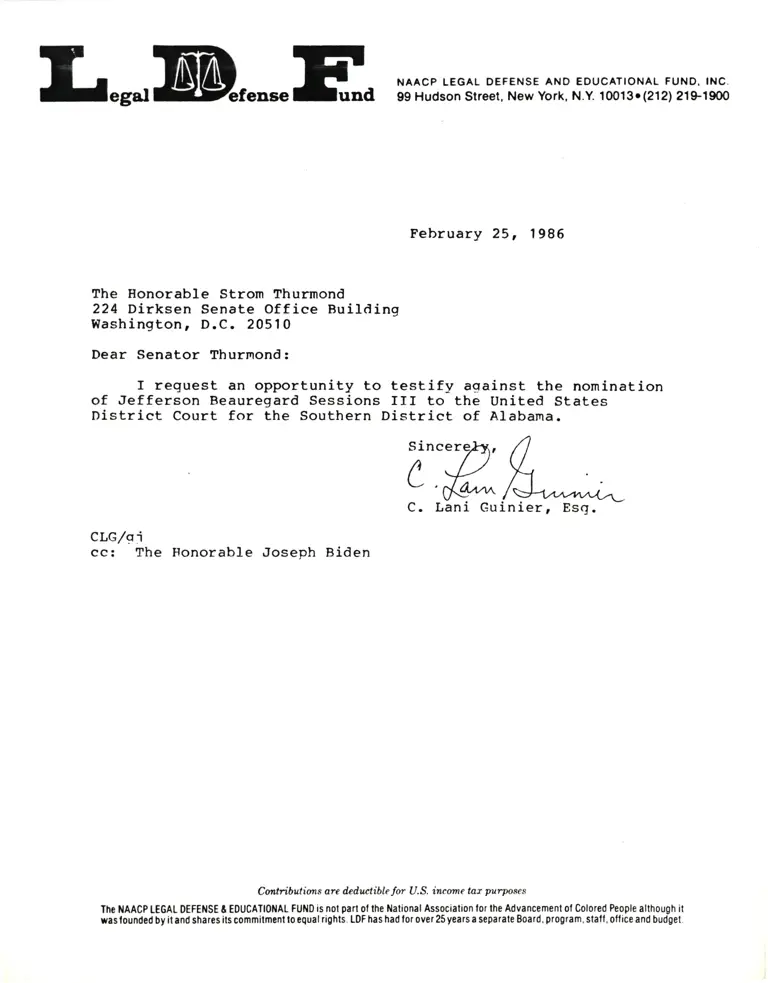

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND. INC.

egal efense und 99 Hudson Street, New York, NY. 10013-(212) 219-1900

February 25, 1986

The Honorable Strom Thurmond

224 Dirksen Senate Office Building

Washington, D.C. 20510

Dear Senator Thurmond:

I request an opportunity to testify against the nomination

of Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III to the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Alabama.

Sincere ,

(i ' dAAA '

C. Lani Guinier, Esq.

CLG/qi

cc: The Honorable Joseph Biden

Contributions are deductible for US. income tamr purposes

The NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE a EDUCATIONAL FUND is not part at the National Association lor the Advancement of Colored People although it

was lounded by it and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had tor over 25 years a separate Board. program. stall, oliice and budget,