In Memoriam: Professor Lani Guinier Tribute by Sherrilyn Ifill

Reprinted by permission of the Harvard Law Review

I first met Lani Guinier in the summer of 1988. She was distracted. It was understandable. She was just weeks away from her departure from the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF), and on her way to begin her academic career at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. I was ushered into her office — the first office directly on the right as you entered LDF’s lower Manhattan offices at 99 Hudson Street.

I had come in response to a call. LDF was looking for someone to fill a one-year fellowship in their Voting Rights Project. The two lawyers who had anchored their voting rights work were both departing LDF — the Director of the Project Lani Guinier, and Pamela Karlan, the brilliant and irreverent litigator who was leaving LDF to teach at the University of Virginia School of Law. LDF was looking for a placeholder. A fellow who, with the continued consultation of Guinier and Karlan, could keep the work of the project going until they could hire a new permanent voting rights attorney. If I wanted the job, I was told I had to come over right away. I was finishing up a fellowship at the national office of the American Civil Liberties Union, and I wanted the job.

And so I arrived, wearing a striped drop-waist summer dress. I was hot and sweaty from the subway, which I’d taken from Times Square down to Tribeca. I had a resume in a folder but otherwise no papers. I had little time to even familiarize myself with the bio of the person who would interview me. Just a little over a year out of law school, I was surely in over my head.

Lani Guinier and Pamela Karlan (2005)

As Lani was interviewing me, she was looking for things in desk drawers. That she was moving was obvious from the boxes in the offices, and that she had other things on her mind was clear as well. She was starting a new job, and I knew that she had a young child (now Harvard Law Professor Niko Bowie). I remember little about our interview except that I was self-conscious in my nonprofessional attire, and that she was mature and pleasant, but not effusive. She was (as I later learned she always was) clear and direct. She seemed relieved that I was there, and not a total idiot. Most of all, I remember that she deemed me competent enough to be kicked upstairs for an interview with Julius Chambers, the then–Director-Counsel of LDF, a week later.

I got the job, and ended up remaining as LDF’s lead voting rights attorney for five years. For the first eighteen months, I worked intensely with Lani, as she continued to act as a consultant. She taught me how to write sound, persuasive briefs (crushing), pressure-tested my theories on cases I wished to file (humbling), and opened me up to the world of voter suppression in the South and the tools we had to fight it. Even more powerfully, Lani opened me up to the possibilities of being both litigator and theorist, of centering the stories and accounts of discrimination faced by our clients not just in the paragraphs of a complaint or pages of a brief, but even in how we talked about what was at stake in our cases. She modeled for me how critical it was to get to the meat of the thing. Not just to present a cognizable claim that would meet the standards for challenges to vote dilution under the Voting Rights Act. But how to try and infuse into your litigation strategy what the clients really wanted. They didn’t just want majority-Black electoral districts. Or to just be able to elect Black officials. The struggle for voting rights, Lani helped me see, was a struggle of Black people in the South to give meaning to their lives as full and first-class citizens, and to be empowered to change the material conditions of their lives. The stakes were higher than winning or losing a case.

Chisom v. Roemer Brief for Petitioners

You could understand what your clients wanted only by talking with them. By listening closely. And by respecting that they were the experts about how power worked in the states, towns, and communities where they lived. Their experiences of racism and disenfranchisement gave them an expertise to which we had to defer. We knew the law. But they knew their lives. Traveling through the South, as LDF lawyers did and still do, compelled us to reckon with the lived experiences of our clients. It was Lani who taught me how to give voice to their truths in our litigation.

At the same time that Lani was reviewing my draft complaints and briefs, she was making her mark as a brilliant and consequential scholar, writing some of the most important and influential academic articles about voting rights. With the trilogy of articles she published between 1989 and 1992, Guinier announced her entry into the scholarly world with a unique, fearless, and powerful voice. Keeping the Faith: Black Voters in the Post-Reagan Era published in the Harvard Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Law Review; The Triumph of Tokenism: The Voting Rights Act and the Theory of Black Electoral Success in the Michigan Law Review; and No Two Seats: The Elusive Quest for Political Equality in the Virginia Law Review were earth-shattering for me. They were my first introduction to a certain kind of legal scholarship, written by a Black woman, grounded in civil rights history and litigation, richly footnoted, and drawing on a wide range of sources from little-known cases, to legal philosophers, to grassroots activists, to the television show Star Search. Although she went on to write many other, more influential articles and books, it was those three initial law review articles, published by Guinier as she transitioned from her life as a full-time civil rights lawyer, that forever shaped and grounded my understanding of what it meant to fuse the work of scholarship, litigation, and activism into an identity and voice as a law professor and public intellectual.

I still have my personally inscribed and well-worn reprints of these important articles. Their publication during those years shaped me as civil rights lawyer. They set a standard for how I wanted to be as a litigator, teacher, and scholar. I wanted to dig deep, as Lani did. I wanted to fully realize the ambitions and aspirations of my clients. There is no doubt that I would not have decided to enter the academy myself, had I not had the example of Lani to show me that I could litigate, theorize, write, and teach. In fact, through Lani, it became clear to me that I could further realize the ambitions of my clients by exploring in my scholarship that which I could not say in the courtroom, but which often more powerfully and accurately addressed the demands and conditions of those I was privileged to represent.

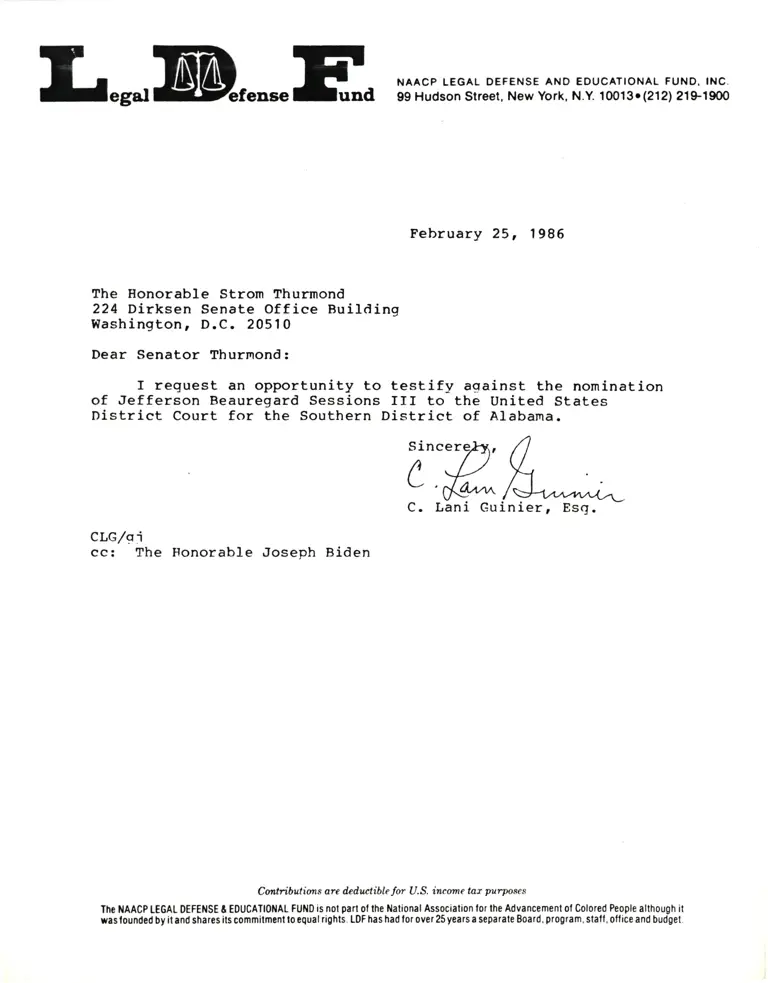

When I returned to LDF as Director-Counsel some twenty years later, Lani was one of the people who was, for me, a touchstone. If she thought I was doing a good job, I would know that I was fulfilling the demands of the enormous mantle placed upon me. Her approval, which she offered generously, meant everything to me. Her offer, after President Donald Trump was elected and announced his first cabinet picks, to just sit in the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing room with me during the Attorney General confirmation hearings for Jeff Sessions, with whom she had tangled some thirty years prior in Alabama (an episode she chronicles powerfully in her book Lift Every Voice

), had us both giggling with gallows humor on the phone. But she knew what was at stake and wanted to help in any way she could.

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Senator Strom Thurmond

Lani Guinier set a standard that I tried to emulate and pass on to the thousands of students I had the privilege of teaching, and that I reinforced during my decade of leadership at LDF. Civil rights lawyer, advocate, scholar, teacher, mentor, leader. Lani Guinier’s influence and pathbreaking contributions to our profession set a standard that continues to resonate across generations.

Former President and Director-Counsel, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.