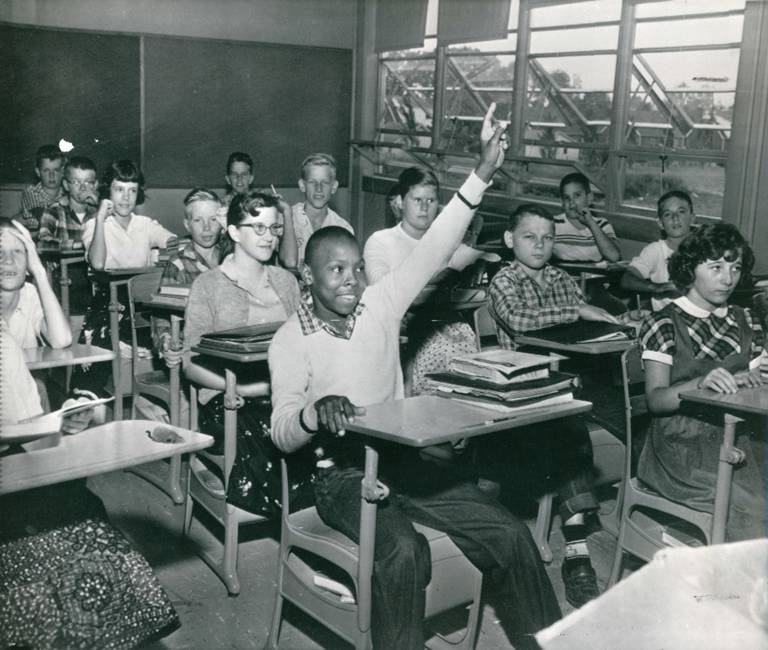

Student Activists Lead in the Fight for Civil Rights

A Black student raises their hand in an integrated classroom. LDF Photograph Collection, School Integration, 1964-1985

W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk, a collection of essays on Black life in the late 19th century and early 20th century, begins with a childhood memory of trading cards. He wrote, “The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card … Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil.” Interrupting the perceived innocence of childhood, Du Bois grounded the reader in the racial caste system of his era. He proceeded to argue that this “veil,” the systemic separation of people by race, breeds contempt, strife, and hopelessness among Black children.

Early awakenings to racial injustice like the one Du Bois described feature prominently in the narratives of countless Black activists. The awakenings serve as a crossroads in their young lives, calling them to act. Both in prior decades and in current social movements, youth activists have responded to the injustice they face in their classrooms and their communities, making vital contributions to the fight for civil rights.

Learn more about student activism in movements for racial justice from the 1960s to the present.

Activists’ Awakenings During the Civil Rights Movement

For James Ferguson, who would go on to collaborate with the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) throughout his career in civil rights, the call to action came early. Born in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1942, he was in the eighth grade when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. In a 2023 interview for the LDF Oral History Project, he recalled excitedly telling his teacher, “Well, Ms. Logan, that means I can go to Lee Edwards High School next year,” at the prospect of being educated at the better-resourced white high school in his community. Despite this initial hope, he also recalled his disappointment as the years passed without Black students being enrolled.

This disappointment sparked the realization that he was part of a racial underclass. He shared, “As a Black young person growing up, it was communicated to us that there were certain things that we were prohibited from doing because we were Black, and that only whites did.”

Tired of accepting this inequity, he began a fight against the school board’s refusal to desegregate Asheville’s schools. As a senior in high school, he joined the Greater Asheville Intergroup Youth Association, a group of Black and white students organized to bridge the gap between the communities. Marvin Chambers, a fellow Black student member of the association, noted in a 2005 interview that Black students’ hopes for integration dimmed during one discussion where students from the all-white Lee Edwards High School argued that their school had more resources simply because their parents were more active in the parent-teacher association (PTA) and fought for them.

Despite these difficulties, Ferguson, Chambers, and their fellow student activists decided to meet with school officials to petition for integration and, at the very least, improved facilities for Black high schoolers. Countering the plans of the PTA chairman and the school board to merely build add-ons to Stephens-Lee, the existing Black high school, the student activists argued that the proposed additions would result in a more crowded school and “would have been nothing compared to what Lee Edwards had.” In support of their demands for real improvements, the student activists drafted a report titled “The Unequal Part of Separate,” which detailed the building’s inadequate structural integrity, equipment, and resources and noted that Stephens-Lee failed to meet state requirements. Ferguson presented this report at a school board meeting and warned the committee that he planned to organize a nonviolent demonstration at Asheville’s white high school. In the months following the meeting, the board agreed to build a new high school for Black students, but they still refused to integrate the schools.

Ferguson’s work to challenge segregation in Asheville did not stop there. He helped found the Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality (ASCORE), a student chapter of the national civil rights group CORE, where he worked toward the successful desegregation of lunch counters throughout the city. Following this work in his hometown, Ferguson earned a bachelor’s degree from North Carolina Central University and a law degree from Columbia Law School. As a lawyer, he returned to the South, where he created the first racially integrated law firm in North Carolina and acted as a fierce litigator in desegregation cases, continuing the work of his youth to realize Brown’s promise.

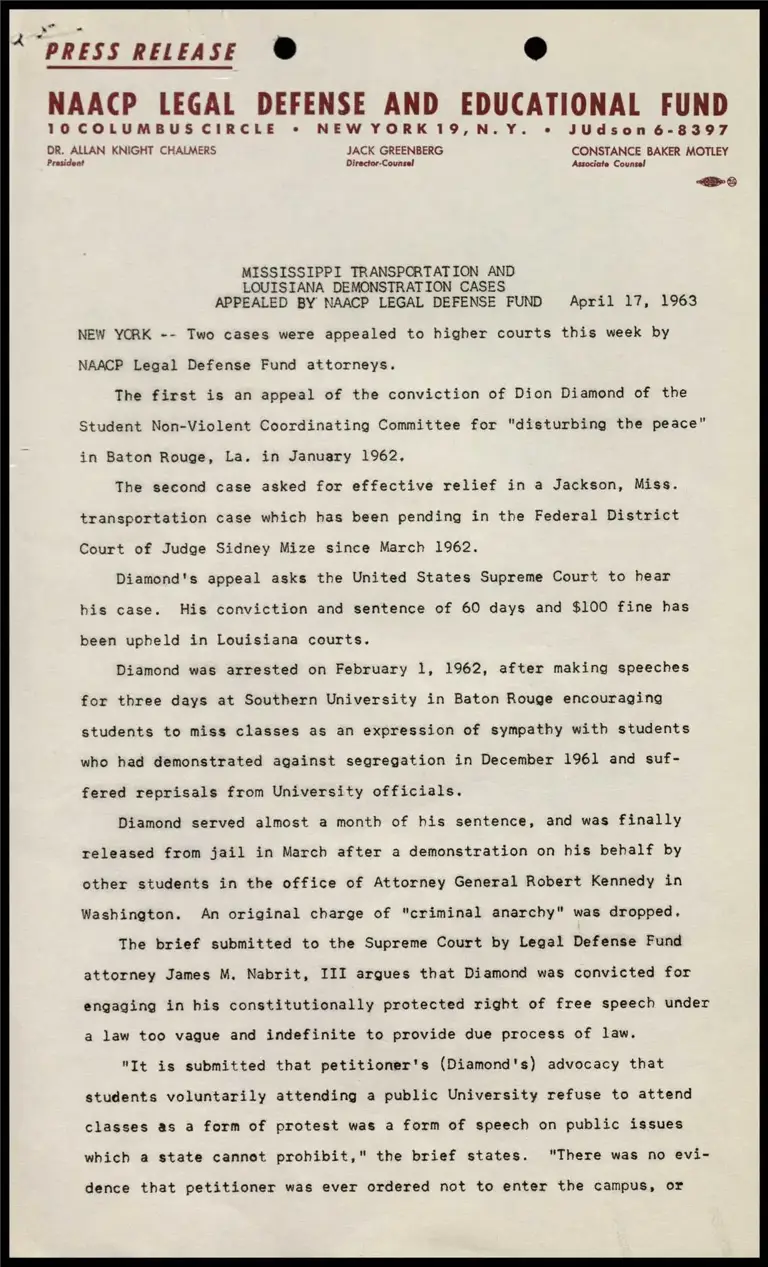

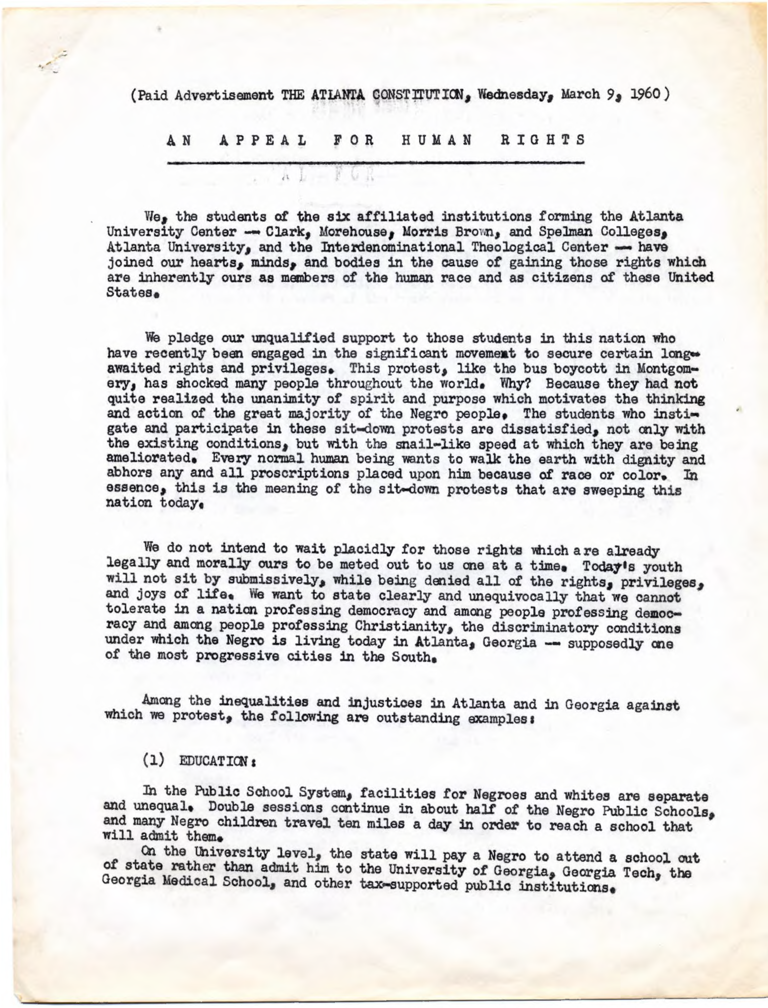

“An Appeal for Human Rights,” Advertisement in the Atlanta Constitution, 1960.

Constance W. Curry papers. Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Robert W. Woodruff Library, Emory University. Civil Rights Movement Archive, www.crmvet.org/docs/aa4hr.pdf

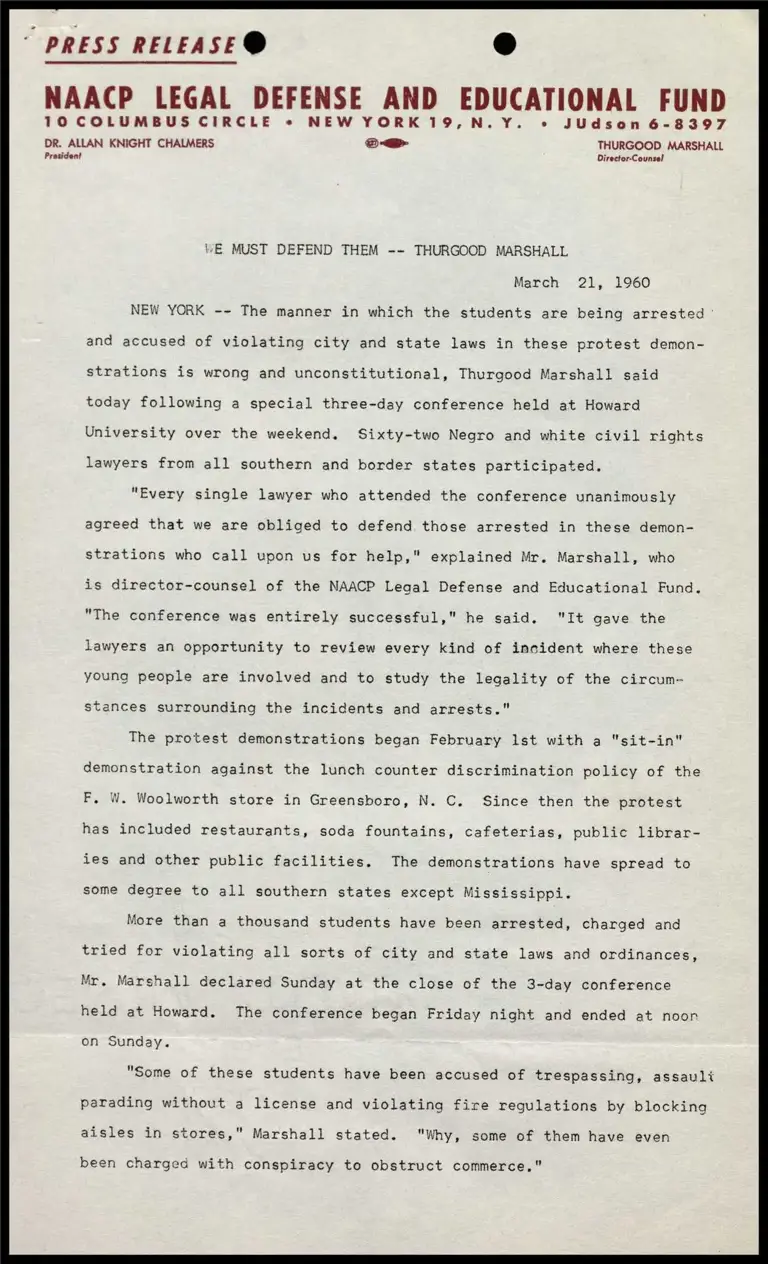

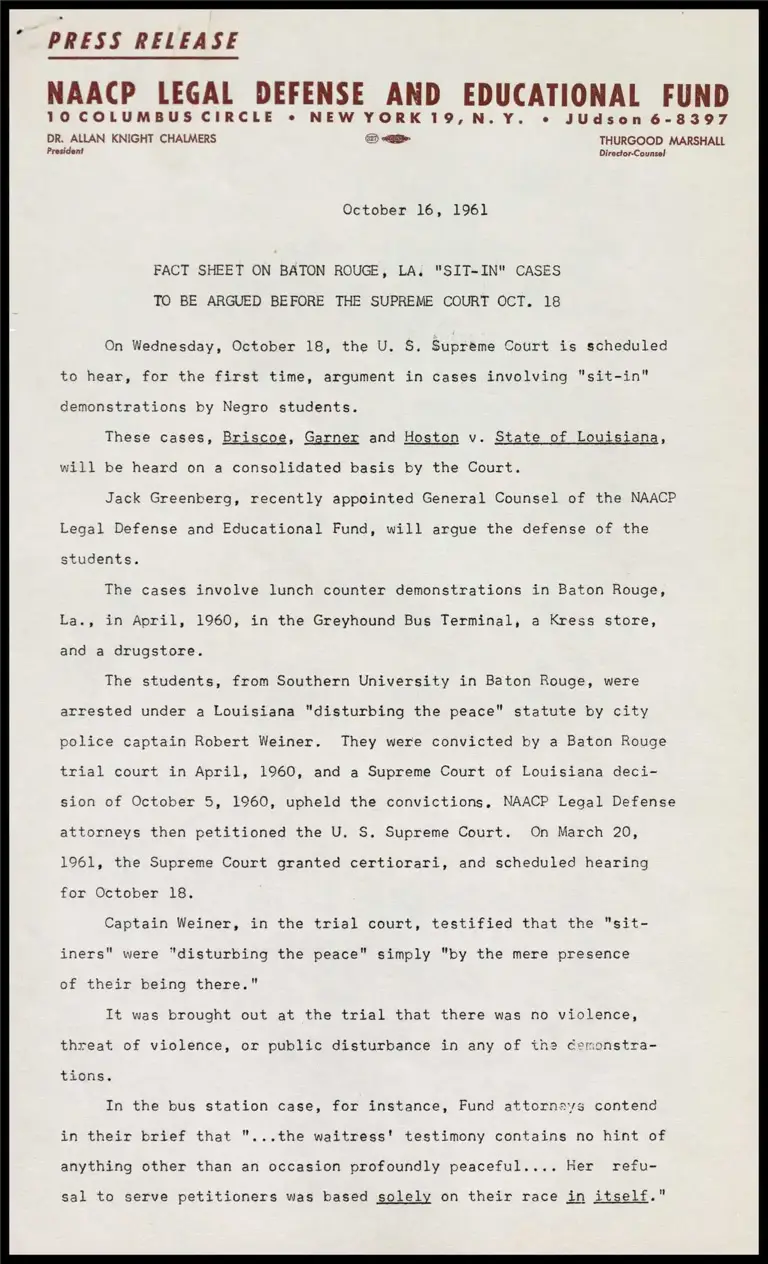

Similarly, former LDF attorney Marian Wright (later Marian Wright Edelman) first witnessed injustice as a child and became an activist as a student at Spelman College. Inspired by the sit-in movement led by university students in Greensboro, North Carolina, she began organizing demonstrations in Atlanta, Georgia. In 1960, she helped draft “An Appeal for Human Rights” with other local student leaders. The document, which acted as a manifesto for the Atlanta Student Movement, declared, “Every normal human being wants to walk the earth with dignity and abhors any and all proscriptions placed upon him because of race or color. … We do not intend to wait placidly for those rights which are already legally and morally ours to be meted out to us one at a time.”

Following the publication of their appeal, the student group organized sit-ins at seven white-only restaurants in Atlanta on March 15, 1960, resulting in the arrests of Wright and 77 other students. Determined to continue their work, the Atlanta students organized a campaign of boycotts and sit-ins throughout the year, which led dozens of stores to desegregate their lunch counters.

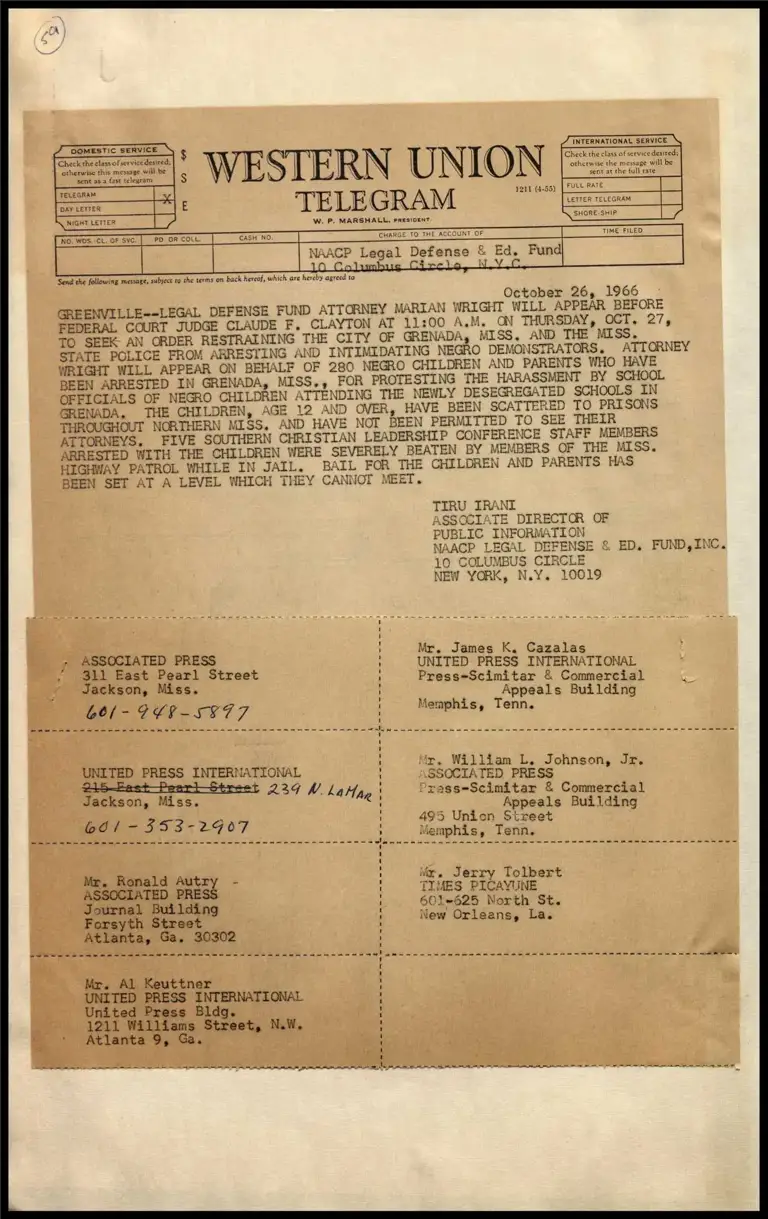

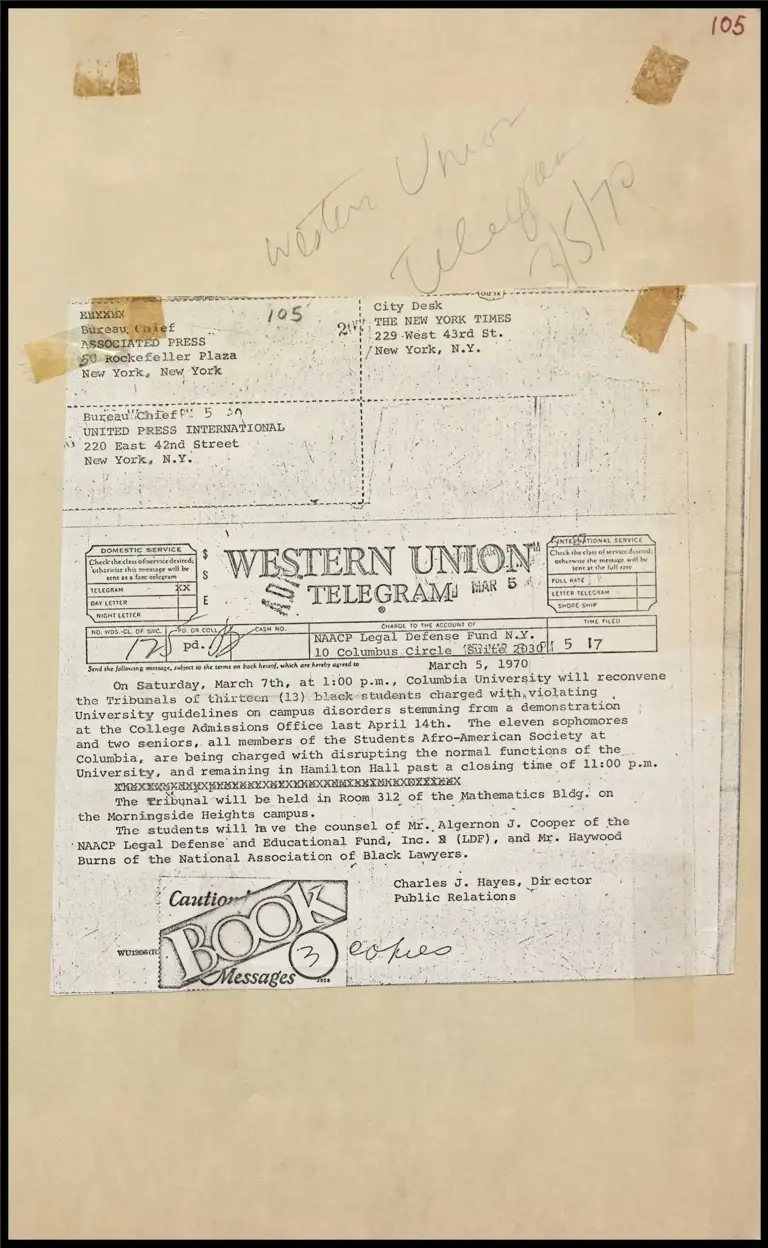

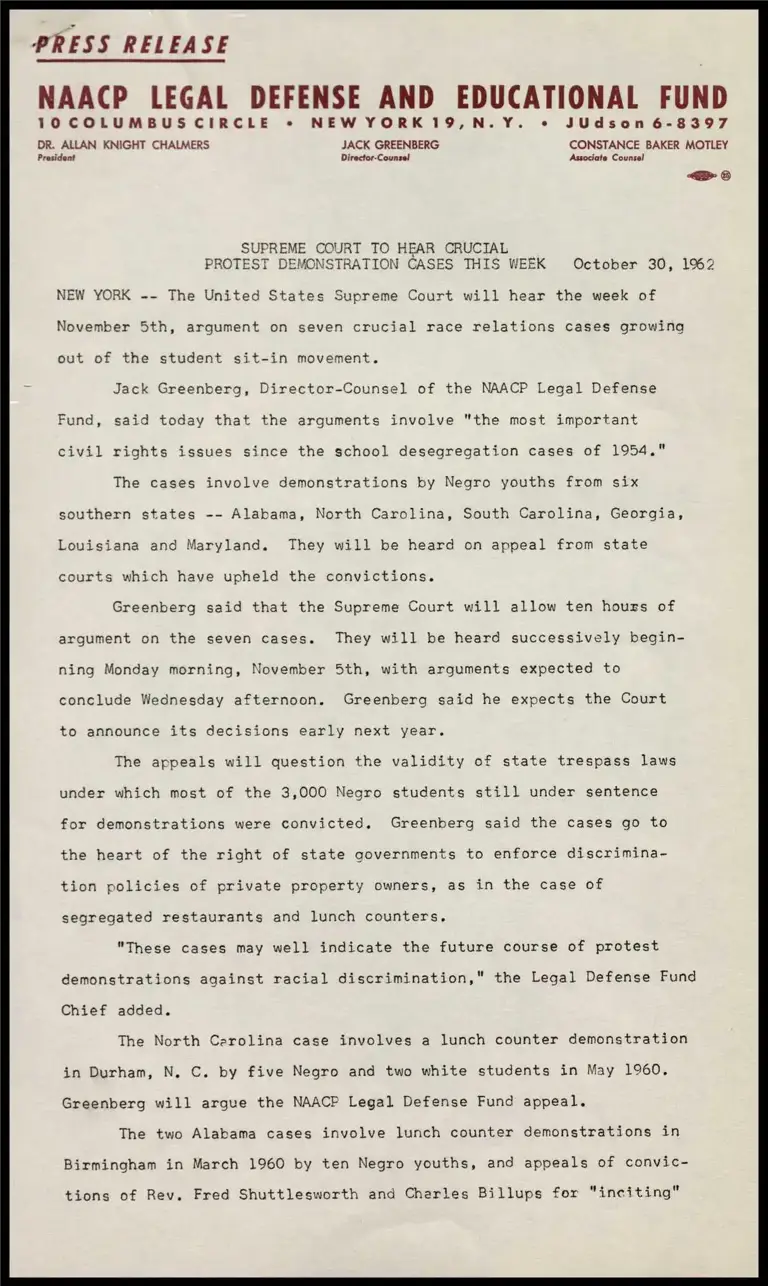

Wright went on to graduate from Yale Law School and to become the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi bar. She directed LDF’s office in Jackson, Mississippi, where she represented college student activists who came from across the country to help secure voting rights for Black people during the 1964 Freedom Summer campaign. She also represented 280 children and parents who were arrested for protesting school officials’ harassment of Black children attending newly desegregated schools in Grenada, Mississippi. Later, she became a key organizer of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign. In 1973, she founded the Children’s Defense Fund to advocate for the rights of young people across the nation.

In her book Lanterns: A Memoir of Mentors, she explained that her own childhood inspired her work to promote opportunity for all children, writing, “My concern for safe places for children to play and swim comes from the lack of public playgrounds for Black children when I was growing up and our exclusion from the swimming pool near my home where I could see and hear white children splashing happily.” Guided by these early experiences with injustice, she has been a key leader in the fight to end child poverty.

Marian Wright Edelman (right), the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi bar, organized LDF’s office in Jackson, Mississippi, where she handled more than 120 cases generated during the Freedom Summer. Also pictured are LDF's then-Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg (left) and Richard Hatcher (middle), then mayor of Gary, Indiana.

Countless other civil rights leaders also got their start as student activists. As a child, former LDF attorney Bill Robinson read Jet magazine on his paper route, looking forward to seeing the regular litigation updates from LDF founder Thurgood Marshall. Robinson knew then he wanted to be a lawyer, but he did not answer the call to civil rights work until later. In his first year at Columbia Law School, he joined the Law Students Civil Rights Research Council (LSCRRC), an effort to organize law students to provide additional legal support for activists working in the South. After months of supporting the project through legal research and writing, Robinson went to Mississippi to participate in the 1964 Freedom Summer campaign.

Robinson described Freedom Summer as a transformational experience for him and for the country. In his 2023 interview for the LDF Oral History Project, he shared, “The brutal denial of the basic right to vote, the basic right to move freely in society and so forth was put on display on the six o’clock news every night.” He said that the nation was particularly shocked by the news that three civil rights workers who had been participating in Freedom Summer were murdered for their activism.

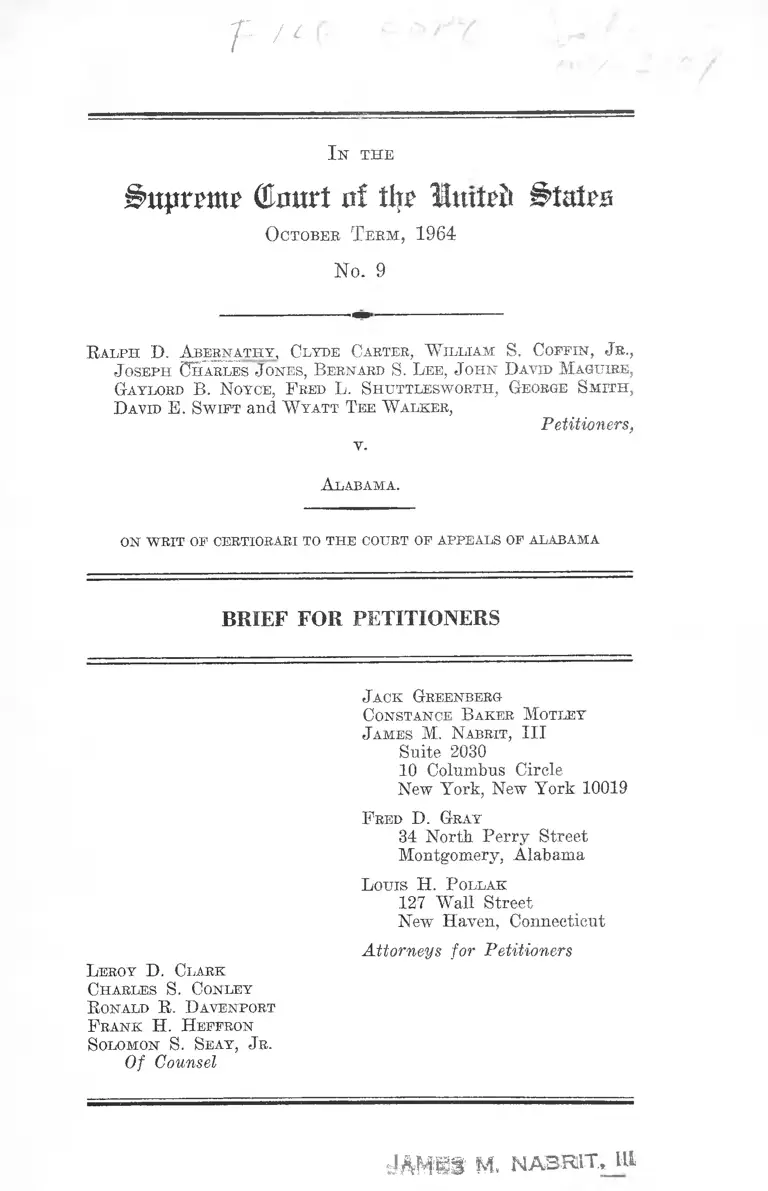

After earning his law degree in 1966, Robinson joined LDF, where he litigated cases related to public accommodations, school desegregation, public housing, and employment discrimination. As a leader of LDF’s employment discrimination practice, Robinson and his team won two Supreme Court cases, Griggs v. Duke Power Co. and McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, that helped strengthen the protections of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and made it possible for lawyers to challenge systemic discrimination and transform national worker protections. Robinson’s team won more than 25 Title VII cases at the federal appellate level during his tenure.

Robinson credited his experience during Freedom Summer with putting him on the path to service as a civil rights lawyer. Reflecting on the campaign, he shared, “I didn’t realize it at the time. I mean, who I was becoming, I was being changed. … I was having a really incredible, deep experience—intellectual, emotional, in terms of friendships, camaraderie. All of that was combining to move me, mold me, if you will.”

Protecting the Right to Protest

Today, youth activists following in the footsteps of advocates like Ferguson, Wright, and Robinson face attacks on the right to protest from courts, legislatures, and police. The U.S. Protest Law Tracker found that between January 2017 and March 2025, federal and state legislators nationwide introduced 339 bills restricting the right to protest and enacted 49 of those bills. In states like Arkansas, Iowa, and Tennessee, these laws mean protesters can be sentenced to a year of jail time for blocking traffic, a tactic often used in demonstrations. Police intimidation has also played a role in limiting the right to peaceful assembly. For example, participants in Black Lives Matter demonstrations in 2020, including many young people, faced tear gas and rubber bullets in response to their calls for racial justice. More recently, several police forces used similar militarized tactics against student activists on college campuses across the nation who were organizing in support of Palestinian rights.

Source: ICNL, US Legislation Affecting Protest Rights: By Year Analysis of US Anti-Protest Bills – ICNL

In the face of these attacks, LDF has been a fierce defender of the right to protest, through litigation, research, and advocacy. LDF filed a lawsuit on behalf of residents of a predominantly Black neighborhood in West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, challenging the Philadelphia Police Department’s use of militarized tactics against peaceful protesters. Under the 2023 settlement terms, the City of Philadelphia agreed to pay more than $9 million in damages to people harmed by this police violence in the summer of 2020. Philadelphia also withdrew from a federal program that arms law enforcement with military weapons, and representatives committed to meeting with the West Philadelphia community every six months to present data on the Police Department’s use of force. Similarly, LDF also filed a complaint against the City of Louisville, Kentucky, in July 2020 to end the use of certain weaponry on peaceful protesters, require policy changes about the limited circumstances in which those weapons could be used, and seek damages for protesters who had been harmed. In 2023, the Department of Justice found that the Louisville Metro Police Department in fact engaged in unconstitutional and unlawful conduct during the 2020 protests, and it began settlement negotiations with Louisville in February 2024.

LDF’s litigation has also focused on the intersection of the right to protest and voting rights, continuing the tradition of the student activists during Freedom Summer. In November 2020, LDF filed a lawsuit on behalf of prospective voters and protesters in Alamance County, North Carolina, who were pepper-sprayed by law enforcement officers while marching to the polls on the state’s final day of early voting and voter registration. LDF and co-counsel challenged the use of intimidation to deter these peaceful protesters, in violation of their civil and constitutional rights.

Learn more about the unequal police response to racial justice protests.

In terms of research and advocacy, LDF’s Thurgood Marshall Institute has conducted critical research on protests. For example, researchers found that during the summer of 2020, demonstrators for racial justice faced mass arrests and felony charges at disproportionate rates compared to participants in other types of demonstrations. This brief affirmed that disparate treatment of racial justice protesters threatens democracy.

Upholding the right to protest is particularly important for youth activists, who continue to spearhead many social movements today and often pursue careers as social justice lawyers. In July 2024, LDF co-authored a letter with several civil and human rights organizations urging the Department of Justice to investigate police treatment of student protests across the country in support of Gaza and the Palestinian people. The letter drew a throughline from the youth protesters of the Civil Rights Movement to today’s students demonstrating for Palestine, highlighting that both groups faced “racialized and excessive police violence” in response to their calls for justice.

Today’s youth activists can draw from the wisdom of past civil rights protesters who fueled a social movement in the face of violence and political repression. Despite institutional pushbacks, James Ferguson refused to accept an unequal education. For Marian Wright Edelman, an arrest was not enough to keep her from protesting segregated facilities. In Bill Robinson’s case, participating in Freedom Summer set him on the path to civil rights law. Just as in the past, youth activists will continue to answer the call to action—transforming themselves and their communities in the process.