National Guard Deployed: Safeguarding Democracy or Serving Autocracy?

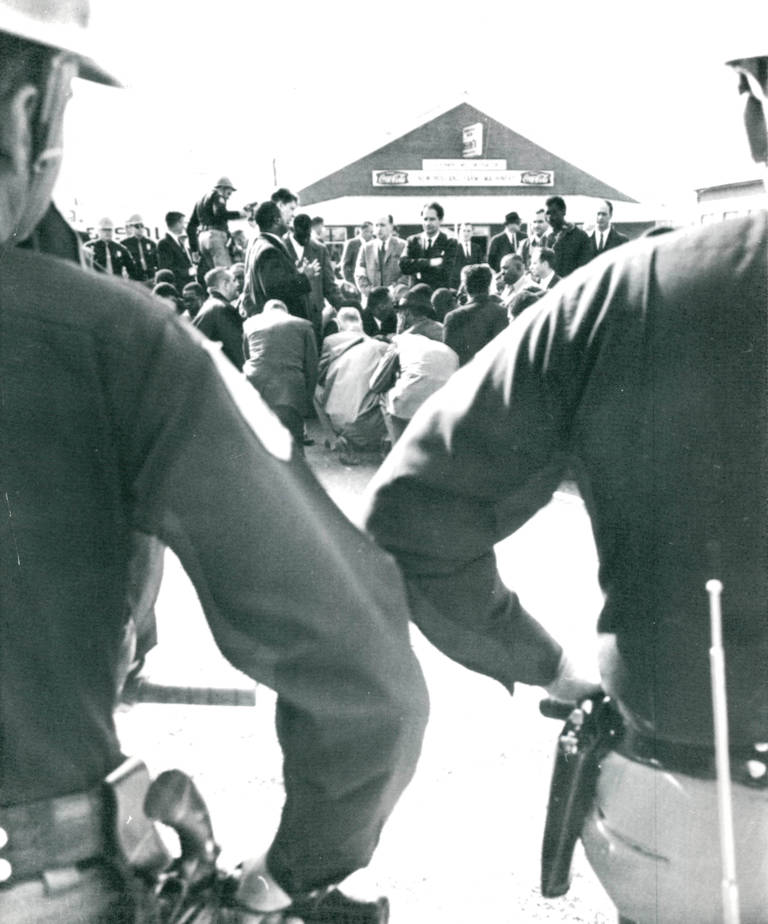

State troopers stand by as demonstrators kneel and pray after their protest march was halted in Selma, Alabama, on March 10, 1965. View in archives

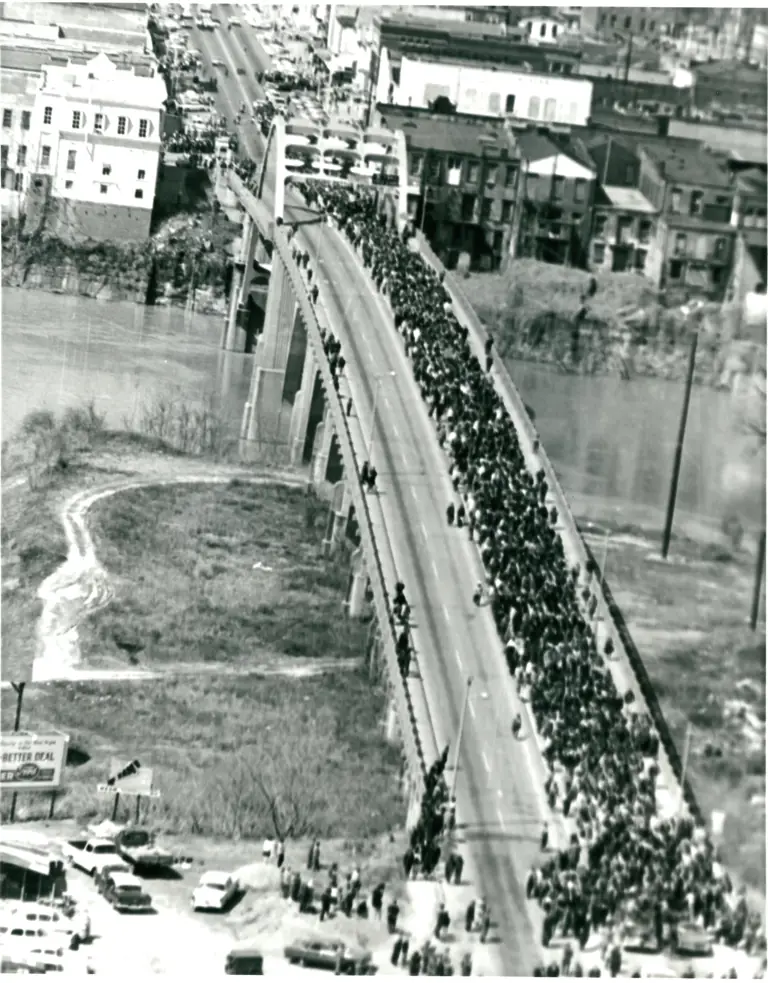

Protesters marching across Edmund Pettus Bridge.

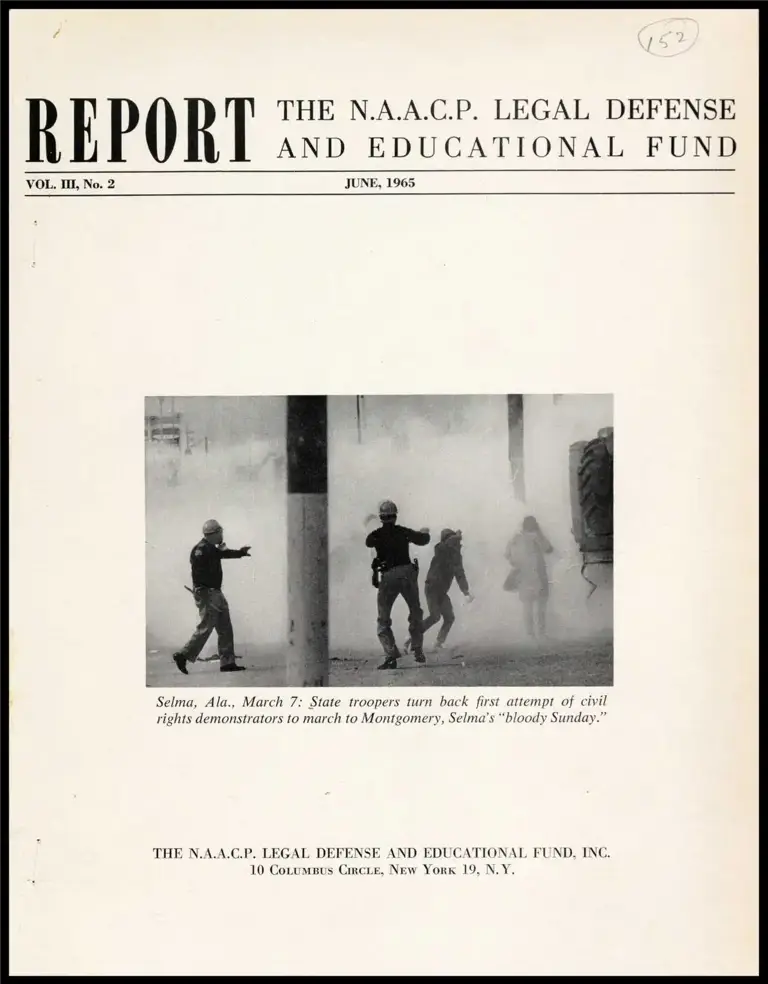

Before this month, the last time a president federalized the National Guard in response to protests was in 1965, to protect civil rights demonstrators marching from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama. Following the brutal treatment of demonstrators on “Bloody Sunday” and the murder of civil rights activist and minister James Reeb, President Lyndon B. Johnson activated the Alabama National Guard to protect these demonstrators. Johnson’s order, which bypassed Alabama Governor George Wallace’s consent, was not typical: In most cases, state officials request the deployment of National Guard troops after determining that local law enforcement is overwhelmed. In bypassing the governor and deploying troops to protect civil rights demonstrators, Johnson affirmed their right to protest and their resistance to segregationist policies.

Who controls the National Guard?

The National Guard is a collection of state-operated reserve groups of Army and Air Force personnel that respond to both state and federal command. Typically, state National Guards are activated by state governors, but under the Insurrection Act, the president may federalize the National Guard to suppress a rebellion that prevents the enforcement of federal laws.

Read LDF’s Report on the Selma to Montgomery Marches

Rather than using this extraordinary power to protect a fundamental right of people working to promote justice, President Donald Trump used the same executive authority on June 7, 2025, to quell demonstrations in Los Angeles, California, against the enforcement by federal immigration agents (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) of a xenophobic anti-immigrant agenda. He did so while bypassing California Governor Gavin Newsom’s consent.

Many officials have warned of the dangers of military involvement in domestic matters. Newsom expressed his disagreement with the federal government’s interference, stating that the move was “purposefully inflammatory and will only escalate tensions.” Additionally, former U.S. Rep. William Enyart, who is also a retired Illinois National Guard General, said that National Guard troops are not adequately prepared to engage with protesters, noting, “At best, a National Guard soldier gets four hours of training a year to do civil disturbance operations.”

National Guard deployment can either uplift democracy or further authoritarian purposes. Unlike Johnson’s intervention in Selma to protect the right to protest, Trump’s deployment of the National Guard does not further the nation’s progress toward a more just, inclusive society. In a memorandum announcing the federalization of the California National Guard, he claimed, without evidence, “To the extent that protests or acts of violence directly inhibit the execution of the laws, they constitute a form of rebellion against the authority of the Government of the United States.” Trump also affirmed that troops may use any “military protective activities” deemed necessary to protect federal personnel and property in Los Angeles. However, on June 12, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California noted that no “rebellion” existed based on the facts before the court, and it granted a temporary restraining order against the president’s use of National Guard troops. Then, on June 19, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed the District Court’s decision, unanimously deciding that Trump’s deployment of the National Guard was likely to be lawful and that judicial review of his action should be “highly deferential.” At the time of publication, the litigation was ongoing.

National Guard troops have facilitated the intimidation and abuse of protesters before. For example, in 1970, the mayor of Kent, Ohio, declared a state of emergency and requested the assistance of the National Guard to suspend anti-war protests at Kent State University following President Richard Nixon’s decision to invade Cambodia and further involve the United States in the Vietnam War. On May 4, 1970, after the Ohio National Guard ordered that demonstrators at a student rally disperse, troops shot into the crowd indiscriminately, killing four people and injuring nine others.

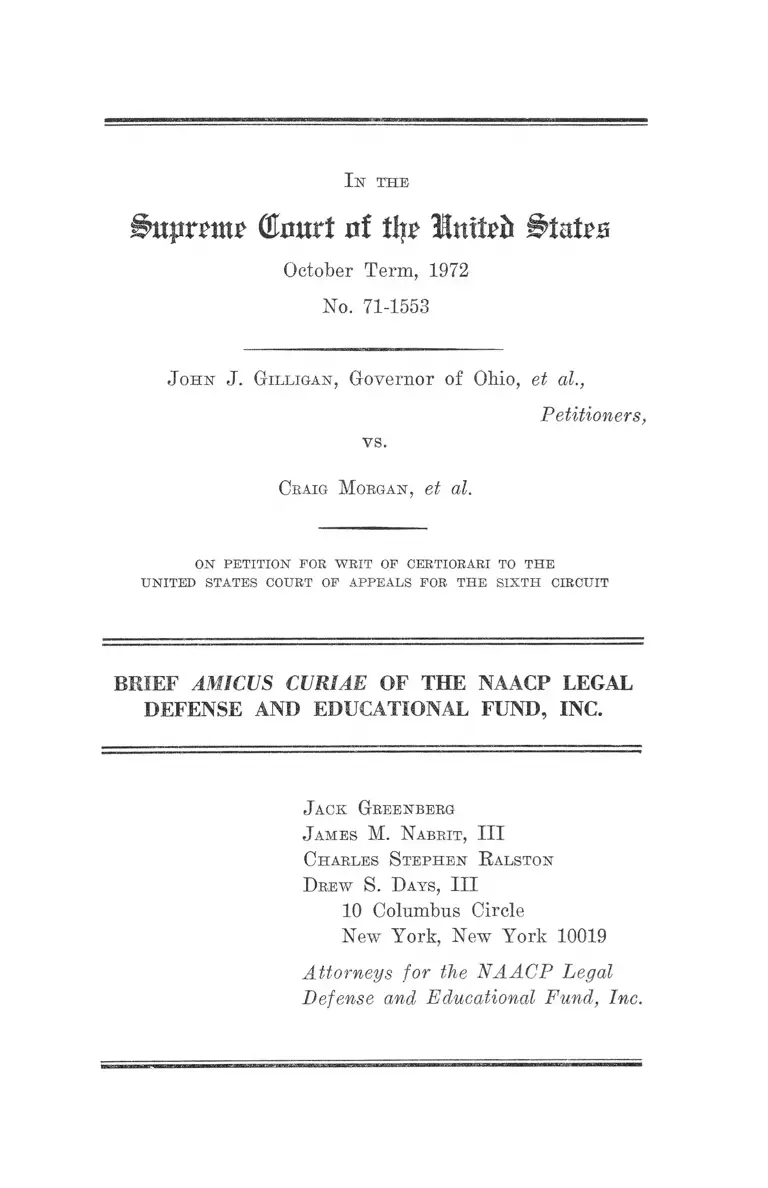

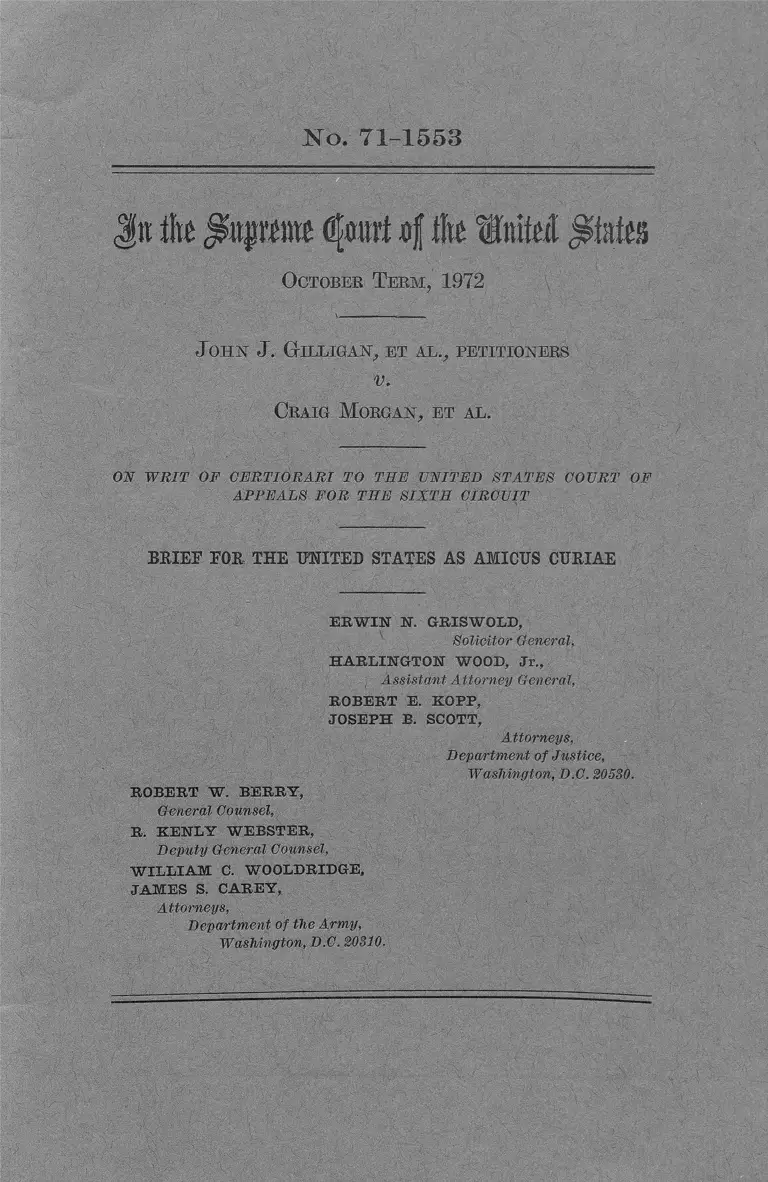

In response, students at Kent State University filed Gilligan v. Morgan, 413 U.S. 1 (1973), against the Ohio National Guard and the governor of Ohio, questioning the use of National Guard troops to restore order on their campus. In defense of the students’ claims that National Guard troops violated their First Amendment rights of speech and assembly, Legal Defense Fund (LDF) lawyers argued in an amicus brief that, following the protests at Kent State, “investigations identified inadequate training and overreaction on the part of law enforcement officials in the use of lethal weapons—in several cases, National Guardsmen—as bearing significant responsibility for the civilian death and injury which resulted.”

Read LDF’s Amicus Brief in Gilligan v. Morgan

The U.S. government’s amicus brief rejected the claim that the “training, weapons, and orders of the Ohio National Guard” deprived Kent State University students of their constitutional rights. Instead, the government argued, “The determination of the proper way in which to prepare members of the National Guard for the performance of their military duties must be made by the military.” The U.S. Supreme Court agreed, holding that the students’ request for judicial review of the National Guard’s training and policies would constitute overreach into the legislative and executive branches’ constitutional powers.

Read the U.S. Government’s Amicus Brief in Gilligan v. Morgan

Regarding the latest conflict, California Attorney General Rob Bonta stated that the Trump administration “far overreached its authority” in deploying the National Guard in Los Angeles. While both federal and state governments have used National Guard troops to protect protesters in some instances and to restrain resistance in others, the Trump administration’s current use of these troops draws from the latter precedent. As in the case of Gilligan v. Morgan, the government is using military powers to justify the abuse of protesters’ rights by National Guard troops. Furthermore, Trump’s federalization of these troops sets the stage for a dangerous expansion of presidential power—one that authorizes presidents to use emergency military powers against demonstrators agitating for social change.