Kristen Clarke, former LDF Attorney and then-President of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, testifies during a congressional hearing on voting rights alongside MALDEF Regional Counsel Andrea Senteno and others. (Photo by Senate Democrats / CC BY 2.0)

LDF and its Progeny: Preserving Due Process and Democracy Around the World

Courtesy of the NAACP, reproduced from the Collections of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

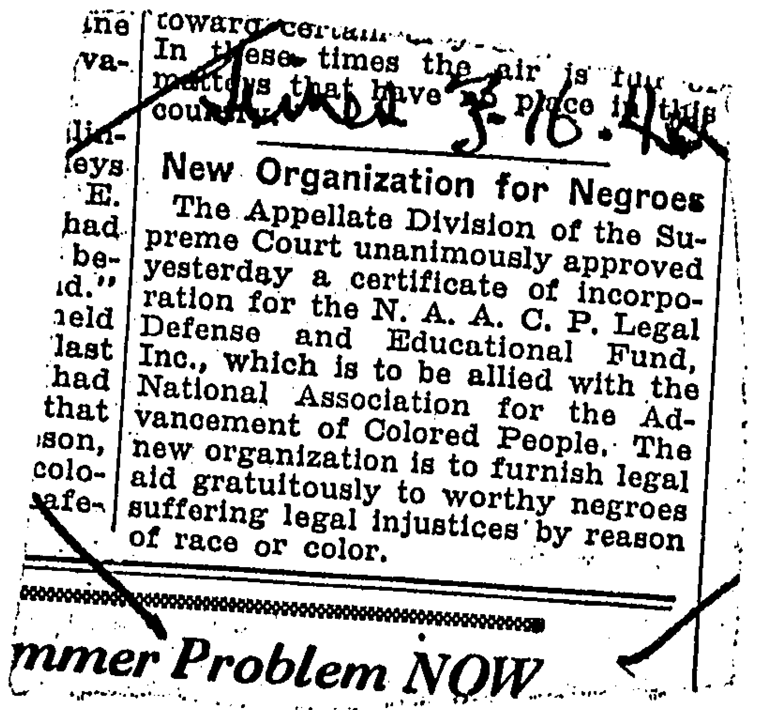

On Saturday, March 16, 1940, a brief news item with the headline “New Organization for Negroes” appeared near the bottom of page six of The New York Times, overshadowed by two eye-catching advertisements heralding newly built “private home apartments” and grand hillside houses for the kind of families “you would like to have as neighbors.”

The short news item announced the unanimous approval by the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court the day before of a certificate of incorporation for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF), explaining that the new organization “is to be allied with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People” (NAACP) and will “furnish legal aid gratuitously to worthy negroes suffering legal injustices by reason of race or color.” There was no mention that Thurgood Marshall, then a special counsel at the NAACP, was LDF’s founder and would become its first Director-Counsel.

The news item was fewer than 60 words, but it heralded an important milestone in Black people’s long struggle for civil rights—one that would not only change U.S. history but would become a model for countless other legal organizations seeking racial equity and justice for all people.

LDF’s Early Days

Two days after the announcement in The New York Times, LDF’s founders prepared a worksheet of tasks necessary for the new organization, including preparing a constitution and bylaws, adding new officers and board members, and giving LDF an official presence in the NAACP’s Fifth Avenue offices in Manhattan.

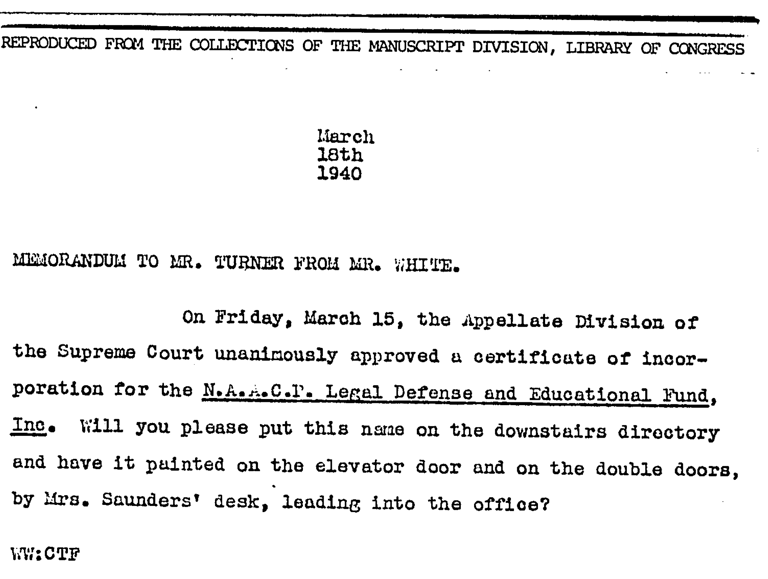

In a memo dated March 18, 1940, NAACP Executive Secretary Walter White requested that Frank Turner, a longtime NAACP employee and the Chief Accountant, put LDF’s name “on the downstairs directory and have it painted on the elevator door and on the double doors, by [NAACP clerk] Mrs. [Gertrude] Saunders’ desk, leading into the office.”

Memorandum from Walter White to Frank Turner, March 18, 1940

Courtesy of the NAACP, reproduced from the Collections of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

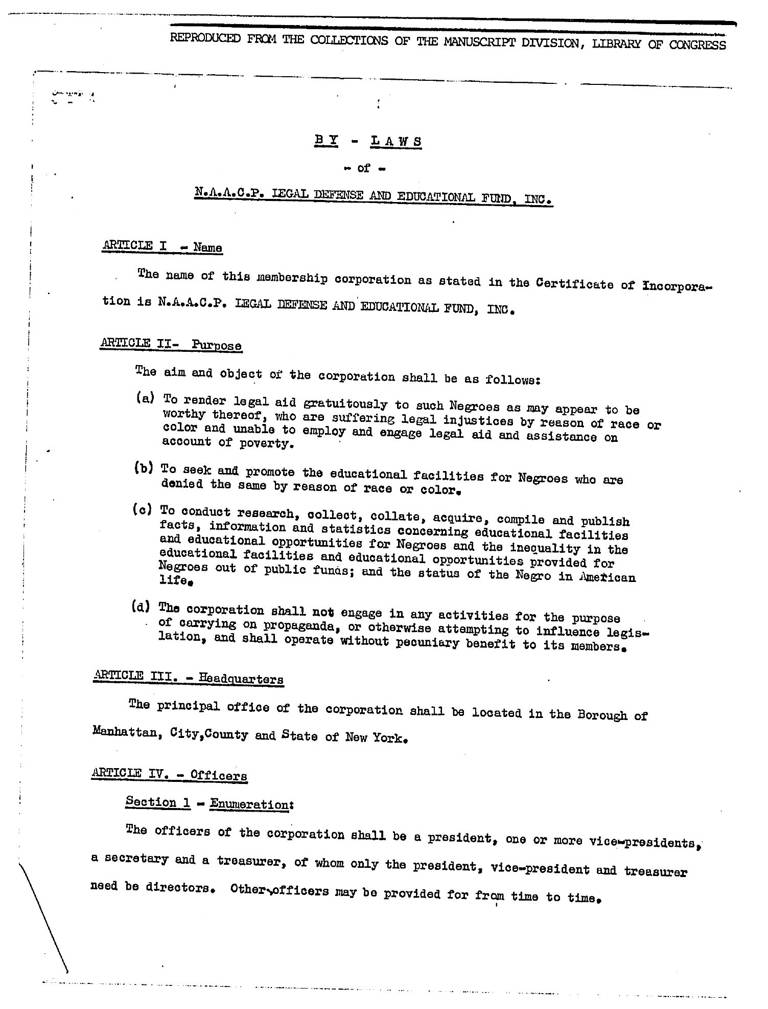

With those tasks in motion, everything became official with LDF’s incorporation on March 20. LDF was intended to be the NAACP’s legal arm to litigate a growing docket of racial segregation, poverty, and criminal cases. LDF’s bylaws stated that the organization’s purpose was: to render legal aid to worthy Black people “who are suffering legal injustices by reason of race or color and unable to employ and engage legal aid and assistance on account of poverty”; to “seek and promote the educational facilities for Negroes who are denied the same by reason of race or color”; and to “conduct research, collect, collate, acquire, compile, and publish facts, information, and statistics concerning educational facilities and educational opportunities for Negroes and the inequality in the educational facilities and educational opportunities provided for Negroes out of public funds” and concerning “the status of the Negro in American life.”

Bylaws of NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

5 pages

Courtesy of the NAACP, reproduced from the Collections of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

By May 1940, the task of separating LDF’s finances from the NAACP’s was under way, with costs such as bookkeeping and travel expenses, the full salaries of Marshall and legal research assistant Cassandra E. Maxwell, and one-third of the rent, light bill, and telephone bill charged to the new organization. This division of duties and expenses was legally necessary for tax purposes, to separate it from the NAACP’s lobbying efforts. As a tax-exempt organization, LDF could accept tax-deductible donations and grants from individuals, companies, and foundations to help pay for staff and expensive litigation costs. There were also political reasons to separate the two organizations: In 1956, provoked by Southern lawmakers, the Internal Revenue Service investigated the NAACP’s tax-exempt status. Although the NAACP’s status was upheld, the NAACP and LDF fully separated in 1957 to help protect LDF from undue legal attacks as it focused on litigating civil rights cases.

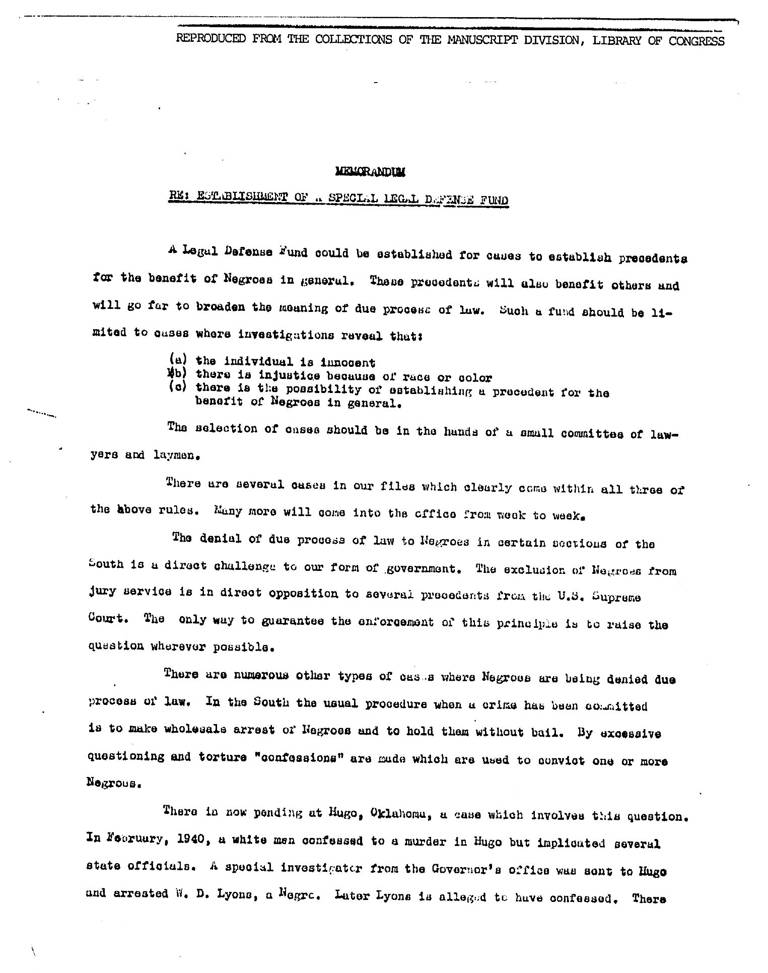

During the creation of LDF, the founders were very clear that they wanted the new organization to work on cases “to establish precedents for the benefit of Negroes in general.” With an eye toward the future, they believed that “these precedents will also benefit others and will go far to broaden the meaning of due process of law.” They determined that LDF would only accept cases—selected by a small committee of lawyers and laypeople—in which “the individual is innocent,” “there is injustice because of race or color,” and “there is the possibility of establishing a precedent for the benefit of Negroes in general.”

Memorandum Re: Establishment of a Special Legal Defense Fund

2 pages

Courtesy of the NAACP, reproduced from the Collections of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

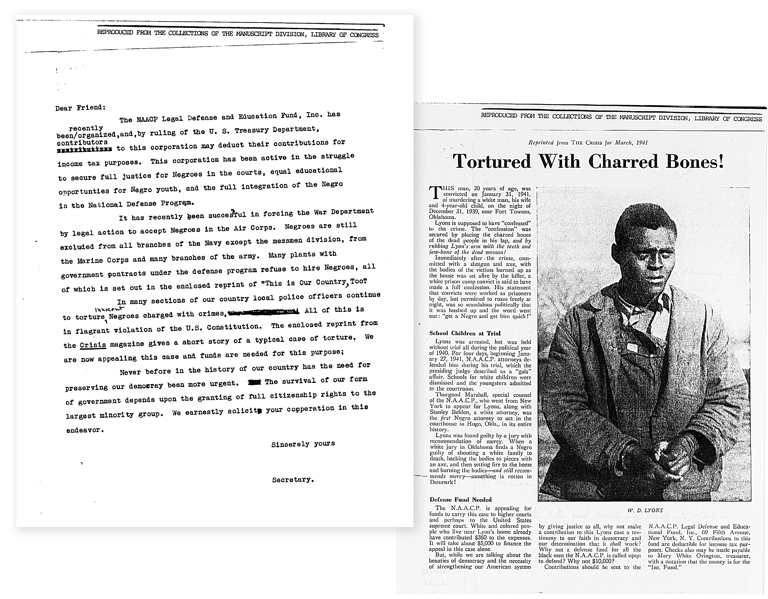

The NAACP had already identified several cases in its files that fit these standards. One involved a young Black farmhand in Oklahoma named Willie D. Lyons, who had been convicted in 1941 of murdering a white couple and their 4-year-old son and setting their house on fire. Lyons confessed to the murders after white interrogators beat him and placed the victims’ charred bones in his lap. In an undated draft of a fundraising letter to prospective donors, LDF officials singled out Lyons’ case and the urgent need for “preserving our democracy.”

“In many sections of our country, local police officers continue to torture innocent Negroes charged with crimes. All of this is in flagrant violation of the U.S. Constitution. The enclosed reprint from The Crisis magazine [the NAACP’s official publication] gives a short story of a typical case of torture. We are now appealing this case, and funds are needed for this purpose. ... The survival of our form of government depends upon the granting of full citizenship rights to the largest minority group. We earnestly solicit your cooperation in this endeavor.”

The corresponding story in The Crisis included the headline, “Tortured With Charred Bones!” above a photograph of Lyons in overalls and handcuffs.

Undated draft of a fundraising letter to prospective donors and reprint of a story in The Crisis titled “Tortured With Charred Bones!”

2 pages

Courtesy of the NAACP, reproduced from the Collections of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Lyons’ case had similarities to Chambers v. Florida, which NAACP lawyers had argued before the U.S. Supreme Court two months before LDF’s incorporation. In Chambers, four Black men confessed to the murder of an elderly white man in Pompano Beach, Florida, after police subjected them to several days of sleep deprivation and threats of violence. Marshall was on the Chambers brief but did not argue the case. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned the men’s convictions because their coerced confessions violated the due process clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

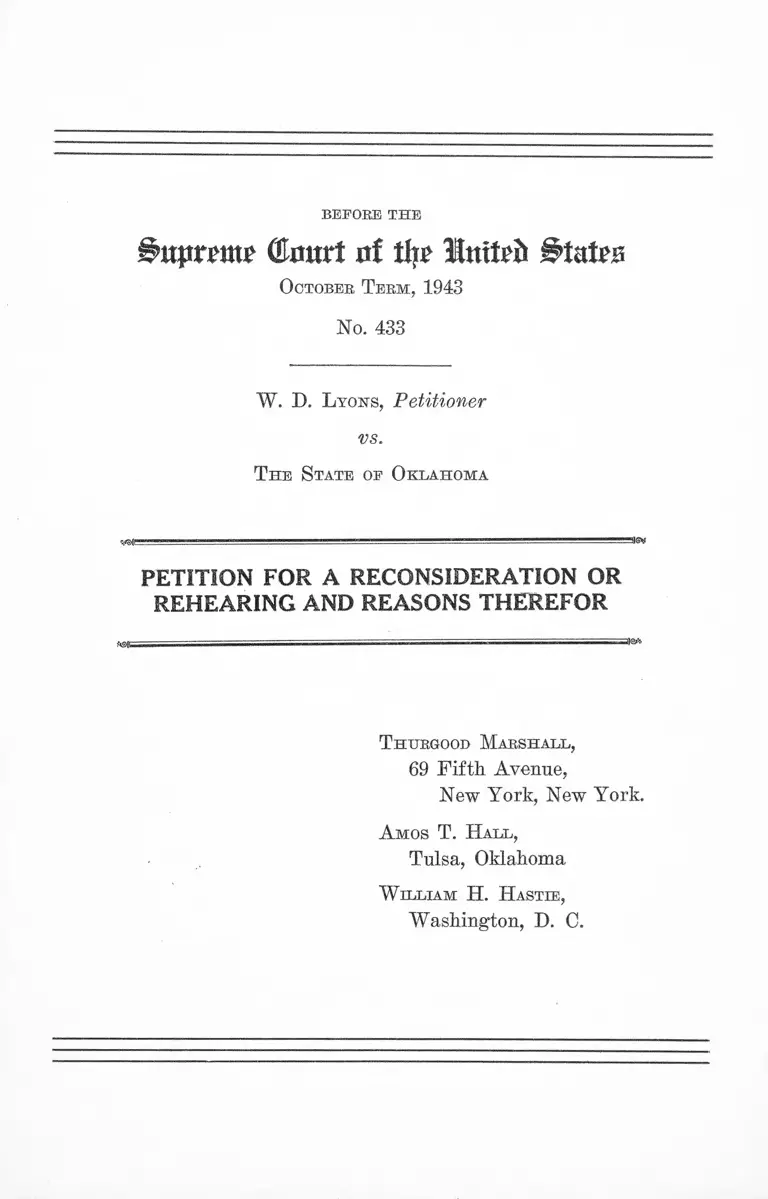

Following that landmark victory, the Oklahoma case was an obvious choice for LDF. But Lyons v. Oklahoma had a different outcome when the case came before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944.

The state said Lyons had confessed three times to the murders, and his last confession was to a guard at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester, where he was transferred after his initial interrogation. Marshall argued that Lyons made the first confession while being tortured, and the subsequent confessions came under the threat of more torture.

In a six-to-three decision, the Court agreed with Oklahoma, ruling that Lyons’ 14th Amendment rights were not violated because his last confession had been voluntary. The decision stated, “The 14th Amendment does not provide review of mere error in jury verdicts, even though the error concerns the voluntary character of a confession. We cannot say that an inference of guilt based in part upon Lyons’ McAlester confession is so illogical and unreasonable as to deny the petitioner a fair trial.” Lyons ultimately served 20 years of a life sentence and was paroled in 1961.

Lyons v. The State of Oklahoma Petition for a Reconsideration or Rehearing and Reasons Therefor

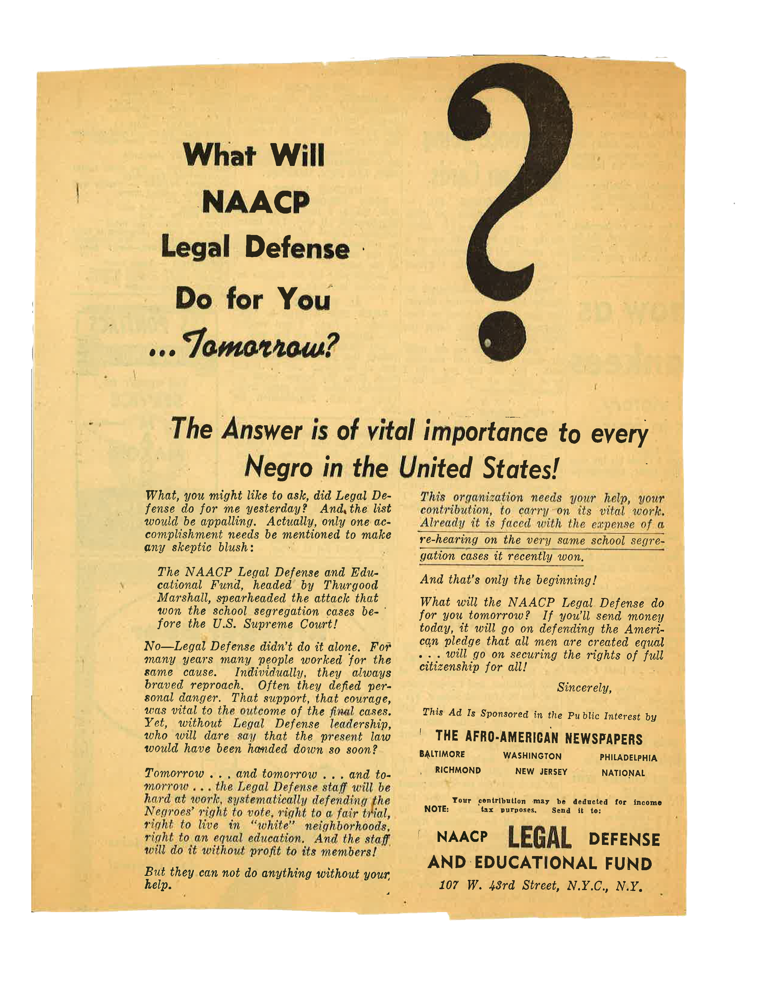

Despite the disappointing loss, the LDF lawyers persisted. Lyons’ case and others tried by LDF throughout the 1940s were a boon for fundraising and membership. By 1946, the NAACP had grown to an estimated 600,000 members. Generous donations helped LDF tackle the goals outlined in its bylaws—including advancing educational equity, which resulted in the landmark 1954 school desegregation ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.

An advertisement for LDF in 1955. (Source: LDF Archives)

Drawing in Talented Lawyers

Constance Baker Motley

LDF’s courtroom endeavors attracted not only new donors, but also talented young lawyers and law students from across the country. Many of these lawyers would become the organization’s and the nation’s “firsts.”

Constance Baker Motley, the daughter of immigrants from the Caribbean island of Nevis, was still a third-year student at Columbia Law School when she joined LDF as a law clerk in 1945 and soon became the organization’s second female attorney. In 1961, she became the first Black woman to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Jack Greenberg (Photo by Don Pollard)

Jack Greenberg, the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland and Romania, joined LDF in 1949 after graduating from Columbia Law School and was the organization’s first white lawyer. He later succeeded Marshall and would lead LDF from 1961 until 1984—longer than any other Director-Counsel to date. At age 27, Greenberg argued two of the five consolidated cases that made up the precedent-setting Brown v. Board of Education, which remains the organization’s most famous case.

Teachers can educate their middle school and high school students about Brown v. Board of Education using the curriculum from Recollection: A Civil Rights Legal Archive.

For Brown, in which Motley also played a key role by drafting the complaint, Marshall assembled some of the best legal minds in the country. The landmark case was argued in 1952 and reargued in 1953. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine that had been in place since its Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896, essentially ending state-sponsored segregation in America’s public schools.

The Brown decision was front-page news in every major newspaper in the country. In The New York Times, the banner headline “High Court Bans School Segregation” dominated the page—a monumental shift from the modest announcement of LDF’s incorporation 14 years earlier.

Nettie Hunt and her daughter Nickie sit on the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court. Nettie explains to her daughter the meaning of the Court’s ruling in the Brown v. Board of Education case that segregation in public schools is unconstitutional. (Photo by UPI/Bettmann via Getty Images)

Learn more about Brown v. Board of Education by listening to the Justice Above All podcast:

Marian Wright Edelman at an event in 2010 (Photo source / CC BY 2.0)

Encouraged by this victory, the fight for civil rights transformed into a national movement. LDF lawyers provided legal support to various civil rights campaigns in the South and represented several leaders of the movement, including Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Muhammad Ali, and others.

As the organization grew, many attorneys of diverse races, genders, and backgrounds bypassed corporate and Wall Street law firms to become civil rights lawyers at LDF. Yale Law School graduate Marian Wright Edelman directed LDF’s office in Jackson, Mississippi, and was the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar. In 1973, she founded the Children’s Defense Fund in Washington, D.C., advocating for the rights and well-being of children of all races, just as she had fought for justice for poor and Black people in the South at LDF.

Creating New Defense Funds

LDF’s dedication and determination in advancing the rights of Black people did not go unnoticed. Other racial and ethnic groups across the country, as well as women and members of the LGBTQ+ community, also experienced injustices such as segregated housing and schools, disenfranchisement, and a legal system that often worked against them.

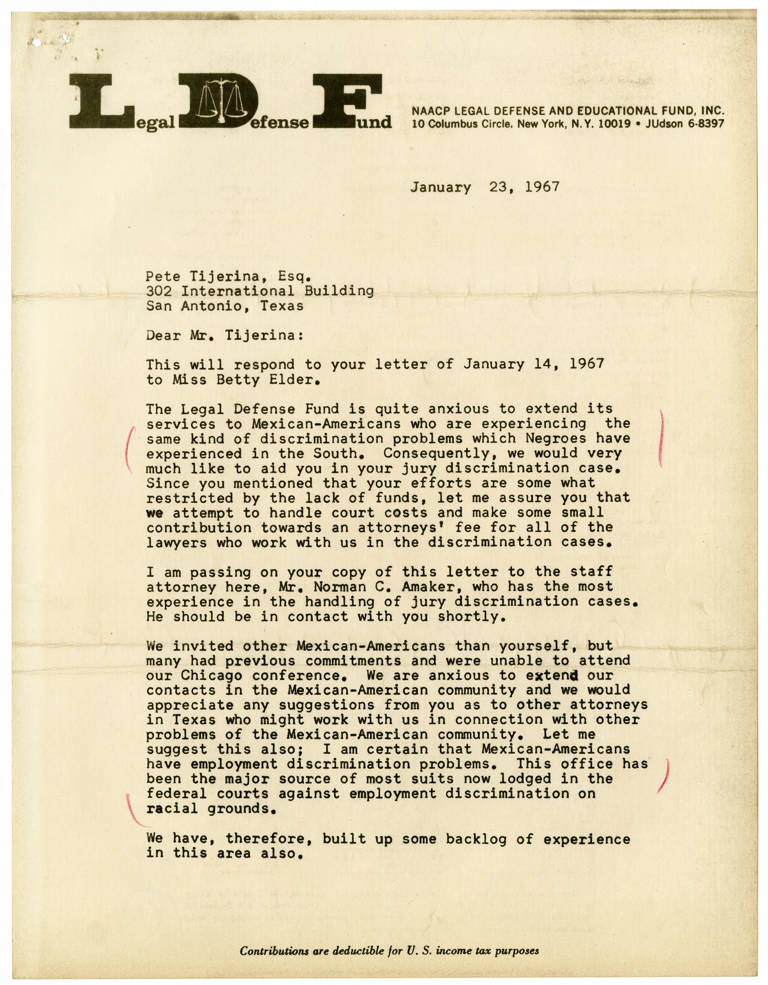

By the late 1960s, LDF was collaborating on cases with other groups, such as Mexican Americans and Native Americans, that did not have their own institutions with the money or staff needed to fight on their behalf. Soon, members of those groups approached LDF Director-Counsel Greenberg for guidance on creating their own legal defense funds. Among them was Pete Tijerina, a Mexican American trial lawyer in San Antonio, Texas. He served as the State Civil Rights Chairman of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), a national organization with more grievances than funds at the time.

In 1954, LULAC celebrated a landmark U.S. Supreme Court victory in Hernandez v. Texas. LULAC challenged an all-white jury’s indictment of a Mexican American agricultural worker in Jackson County, Texas, for the murder of another Latino man. No Mexican American had served on a jury in Jackson County in 25 years. The state of Texas argued that the 14th Amendment only protected two classes: white and Black. In a unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the state’s “two-class theory,” ruling that Texas’ system of selecting jurors that excluded “otherwise eligible persons from jury service solely because of their ancestry or national origin is discrimination prohibited by the 14th Amendment.” Although Hernandez was once again found guilty in a new trial that included Mexican American jurors, the Court’s ruling helped break down barriers by setting a standard that the 14th Amendment applied to Latinx people and other racial and ethnic groups across the country.

Despite this victory, obstacles remained. Around 1965, Tijerina represented a Mexican American woman from Charlotte, Texas, who sued a white driver who crashed into her car, resulting in the amputation of her right leg. When Tijerina showed up for jury selection, he discovered that the jury list did not include a single Mexican American person. A complaint to the presiding judge produced a second list that included two Mexican American jurors. However, “one had been dead for 10 years, and the other one didn’t speak a word of Spanish,” Tijerina, who died in 2003, recalled in an interview in 2000 with the U.S. Latinos & Latinas and World War II Oral History Project of The University of Texas at Austin. Tijerina felt he had no choice but to settle the lawsuit for considerably less than what his client sought. Frustrated with the outcome, he reached out to Greenberg at LDF seeking advice.

Greenberg responded in a January 23, 1967, letter: “The Legal Defense Fund is quite anxious to extend its services to Mexican Americans who are experiencing the same kind of discrimination problems which Negroes have experienced in the South. Consequently, we would very much like to aid you in your jury discrimination case. ... We are anxious to extend our contacts in the Mexican American community and we would appreciate any suggestions from you as to other attorneys in Texas who might work with us in connection with other problems of the Mexican American community.”

Letter from Jack Greenberg to Pete Tijerina, January 23, 1967

This letter is part of the collection entitled: Texas Cultures Online and was provided by the Houston History Research Center at Houston Public Library to The Portal to Texas History, a digital repository hosted by the UNT Libraries.

LDF had previously worked on cases related to discrimination in jury selection, including the successful 1964 U.S. Supreme Court case Coleman v. Alabama, argued by LDF’s Michael Meltsner, in which a Black man’s murder conviction had been handed down in an Alabama county where Black people were systematically excluded from sitting on juries. LDF had plenty of expertise to guide Tijerina.

Coleman v. Alabama Brief for Petitioner

Coleman v. Alabama Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama

Greenberg added, “Let me suggest this also; I am certain that Mexican Americans have employment discrimination problems. This office has been the major source of most suits now lodged in the federal courts against employment discrimination on racial grounds. We have, therefore, built up some backlog of experience in this area also.”

But Tijerina had something else mind: a legal defense fund specifically for Mexican Americans, modeled after LDF.

“It was important to the movement and to the cause and to the Mexican American community to have our own lawyers fight our own cases,” Tijerina explained in the 2000 interview.

Greenberg connected Tijerina with the Ford Foundation, and in 1968, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) was established in San Antonio with a five-year, $2.5 million grant from Ford that also included $250,000 for scholarships for Mexican American law students. Tijerina became MALDEF’s first Executive Director. Vilma Martínez, who previously handled cases representing poor clients at LDF, became MALDEF’s first female President and General Counsel in 1973.

In 1970, as Greenberg worked with Native American groups to create a similar legal defense fund, the Ford Foundation made a grant to California Indian Legal Services (CILS) to establish the national Indian Rights Fund, now the Native American Rights Fund (NARF). NARF and CILS became separate organizations in 1971.

Greenberg also helped create the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, now known as LatinoJustice PRLDEF, in 1972, and the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund in 1974. Both organizations later moved into the same Manhattan building as LDF “and sometimes shared our facilities,” Greenberg wrote in his 1994 book, Crusaders in the Courts: How a Dedicated Band of Lawyers Fought for the Civil Rights Revolution.

LDF regularly collaborated with these newer groups. LDF and MALDEF, along with the Asian Pacific American Legal Center, worked together on the employment discrimination case Gonzalez v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, Inc., in which the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California approved a consent decree in 2005 requiring the clothing store to institute significant reforms to promote workforce diversity and pay plaintiffs more than $40 million in relief for discriminating against Black, Latinx, and Asian American employees and applicants in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the California Fair Employment and Housing Act.

LDF and MALDEF hold a joint press conference to discuss Gonzalez v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, Inc.

Greenberg also consulted with members of the LGBTQ+ community to help set up the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund (now called Lambda Legal) in 1973. Other civil rights institutions established during this era include the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, created in 1963 at the request of President John F. Kennedy to mobilize the private bar in support of civil rights, and the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund (now called Legal Momentum), founded in 1970 to protect women’s rights.

With the growth of legal defense funds and public interest law firms in the United States, LDF turned to human rights beyond America’s shores.

Fighting for Justice Abroad

By the late 1970s, LDF’s role in the fight for civil rights had made an enormous impression on human rights groups abroad, several of which invited Greenberg on missions with the aim of “exporting the idea of American rights to other lands.” This international work built upon the legacy of Marshall, who had served as a legal advisor to Kenyan leaders during their country’s independence process in the early 1960s. As Marshall’s successor, Greenberg met with refuseniks in the Soviet Union and activists in the Philippines, but his 1978 visit to South Africa produced particularly impactful results. A group of lawyers there “had heard about LDF and wanted to explore the possibilities of public interest law in South Africa,” Greenberg wrote in Crusaders in the Courts.

South Africa’s brutal apartheid system of racial segregation, in place from 1948 to the early 1990s, mirrored the ruthless Jim Crow laws of the American South in advancing white supremacy. Greenberg lectured at universities around South Africa about the evolution of civil rights law in America. One enduring outcome of his visit was the creation of the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) in 1979 by Arthur Chaskalson, Felicia Kentridge, and Geoff Budlender, with the goal of challenging apartheid laws. In addition to helping dismantle apartheid, the LRC worked to abolish the death penalty and to advance the rights of women, girls, and people with disabilities in South Africa. Headquartered in Johannesburg, the LRC now also has offices in Cape Town, Durban, and Makhanda. Chaskalson became the first President of South Africa’s new Constitutional Court after apartheid fell and served as Chief Justice of South Africa from 2001 to 2005. LDF continued to foster democracy in South Africa: Ted Shaw, LDF’s fifth President and Director-Counsel, led several delegations to South Africa to help train members of the Black Lawyers Association in response to an invitation from Nelson Mandela.

While Greenberg was encouraging the growth of legal defense funds at home and abroad, Marshall, his predecessor, was serving as the first Black justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Marshall used his long tenure on the high court to uphold racial justice, equality, and inclusivity for all people. He knew that advancing democracy and equity required patience and adaptability.

Today, LDF continues to adjust, adapt, and, in some cases, re-fight old battles in an ever-evolving world. Its legacy is reflected in its own sterling courtroom record and in the accomplishments of other legal defense funds and human rights organizations in the United States and around the globe that have used LDF as their model in advocating for racial justice and preserving democracy for all people.