Legend for Map of House District 23

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Legend for Map of House District 23, 1982. 93f753ca-df92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52c61d00-282c-4981-b3dd-475772ee4f19/legend-for-map-of-house-district-23. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

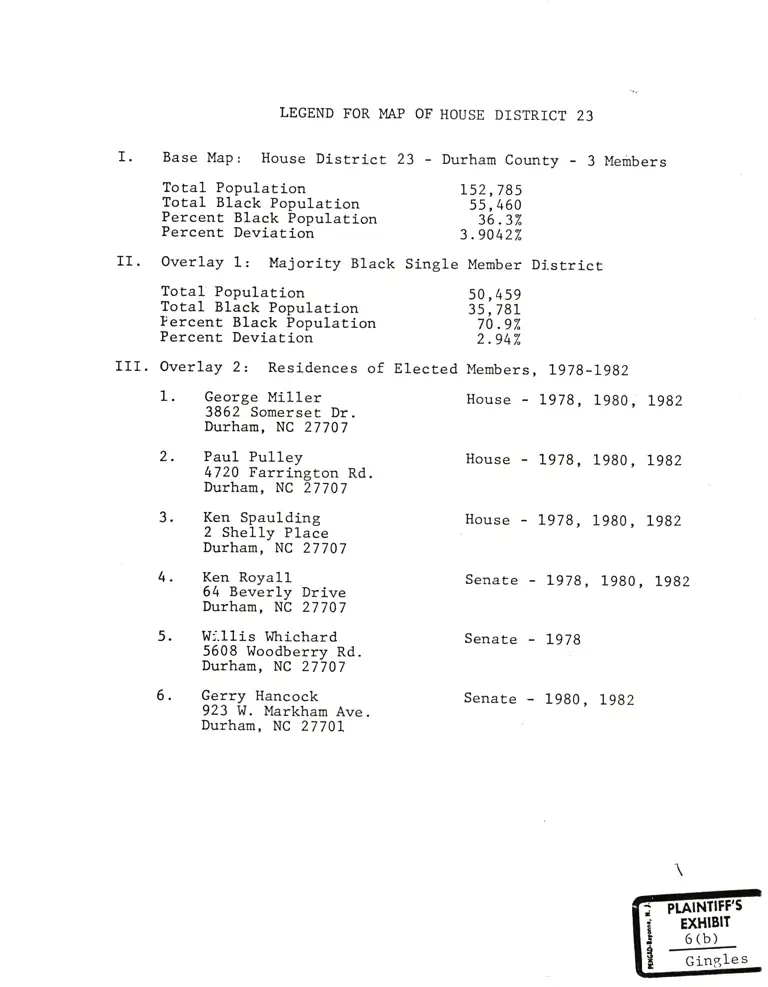

LEGEND FOR MAP OF HOUSE DISTRICT 23

r. Base Map: House District 23 - Durham county - 3 Merirbers

Total Population 152,785

Total Black Population 55',460

Percent Black Population 36.32

Percent Deviation 3.90427.

rr. overlay L: Majority Black single Member Di.stricr

Total Population 50,459Toral Black popularion 35;7gL?ercent Black Population 70.92

Percent Deviation 2.942

rrr. overlay 2z Residences of Elected Members, LgTg-Lgg2

1. Georgg Mil-ler _ House - Lg7g, 19g0 ,. Lgg2

3862 Somerset Dr.

Durham, NC 27707

2. Paul Pulley House - Lg7g, 19g0, L9g2

4720 Farringron Rd.

Durham, NC 27707

3. Ken Spaulding House - L979, 19g0, Lgg22 She1ly Place

Durham, NC 27107

4. Ken .Royal1- _ Senate - Lg7g, 1,9g0 , Lggz64 Beverly Drive

Durham, NC 27107

5. trI:.lLis lJtrichard Senate - LgTg

5608 Woodberry Rd

Durham, NC 27707

6. Gerry- Hancock Senate - 19g0 , Lggz

923 W. Markham Ave.

Durham, NC 2710L