Pugh v. Hunt Motion Pro Hac Vice; Order

Public Court Documents

January 29, 1982 - February 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Pugh v. Hunt Motion Pro Hac Vice; Order, 1982. 756e2dbb-d792-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/548dc511-b426-4f48-acd3-5e977ed43ad7/pugh-v-hunt-motion-pro-hac-vice-order. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

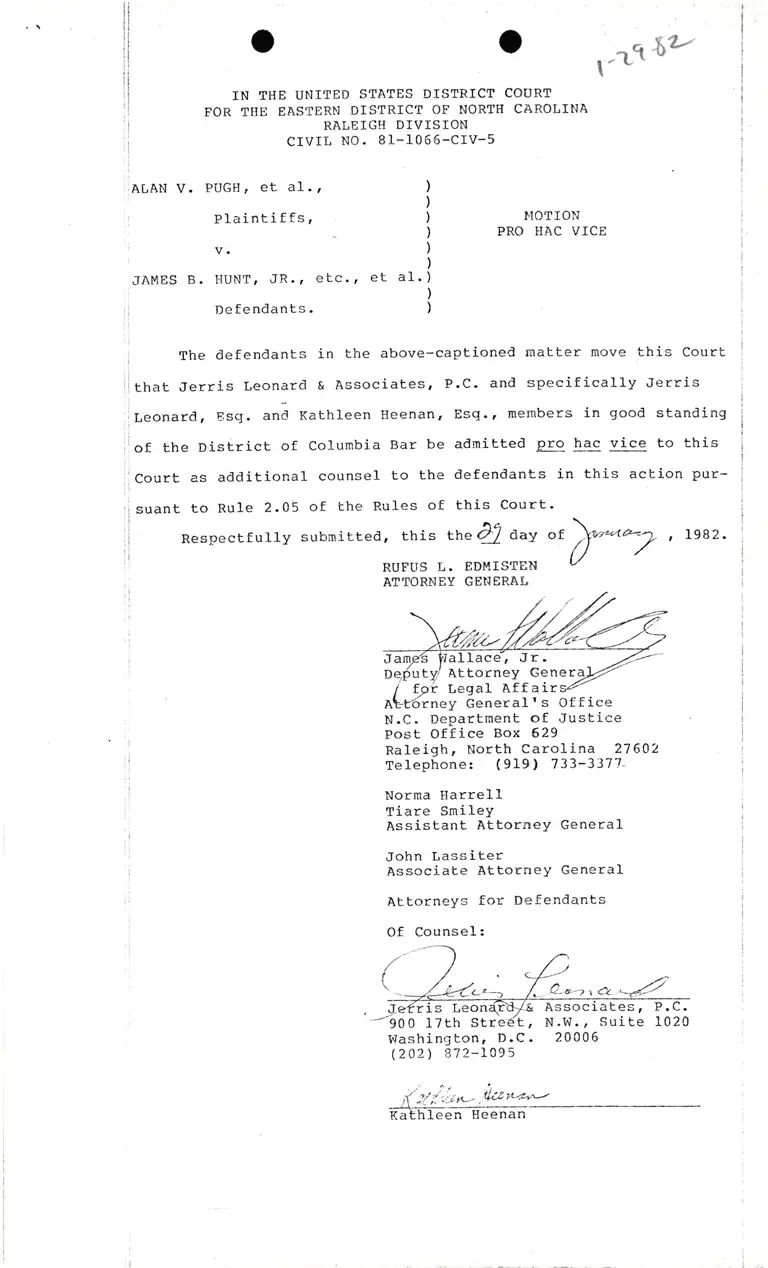

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

CIVIT NO. 8T-IO66.CIV.5

MOTION

PRO HAC VICE

I

-at $?/

P. C.

1020

ALAN V. PUGH, €t a1.,

Plainti ffs,

v.

JAI'IES B. HUNT, JR., ETC., €t AI.

Defendants.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

The defendants in the above-captioned matter move this Court

that Jerris Leonard & Associates, P-C- and specifically Jerris

Leonard, Esq. unl Kathleen Heenan, Esq.' members in good standing

of Lhe Oistrict of Columbia Bar be admitted pro hilc vice to this

Court as additional counsel to the defendants in this action pur-

suant to RuIe 2.05 of the Rules of this Court'

Respecrf urty submitted, this *e fi day of h^*Z , Lgg2.

RUFUS L. EDI4ISTEN U ./

N.e. Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

RaIeigh, North Carolina 27602

Telephone: (919) 733-3377-

Norma Harrell

Tiare SmiIeY

Assistant AttorneY General

John Lassiter

Associate Attorney General

Attorneys for Defendants

Of Counsel:

'- Q-*-'r. a

/

\

Washington, D.C.

(202) 872-1095

Associates,

N.w., Suite

20006

,( ;i X' t 1; *-, tlie r-2"'-

Kathleen Heenan

ATTORNEY GENERAL

allaee, Jr.

uty/ ettorney Gener

fgf r,egal Aff air

rney Generalrs Office

J.s{ris Leonairtl/a'-go o 17 th stredt ,

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FoR rHE rorrrllrBlSfiT;$r3loilottH CARoLTNA

crvrL NO. 8I-1066-CrV-5

ALAN V. PUGH, €t al. r

Plaintiffs,

ORDER

v.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR.r etc., et al.

Defendants.

FOR GOOD CAUSE SHOWlr, it is hereby oRDERED that Jerris

Leonard & Associates, P.C., and specifically Jerris

Leonard, Esg., and Kathleen Heenan, Esq., be admitted

pro hac vice to this Court as additional counsel to the

defendants in this action, pursuant to Rule 2.05 of the

Rules of the Court.

This the day of , L982.

DiEErict Court Judge

aF--

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that f have this day served the foregoing

Motion Pro Hac Vice and Proposed Order upon Plaintiff's attorneys

by placing a copy of same in the United States Post officer postase

prepaid, addressecl to:

J, Levonne Chambers

Leslie Winner

Chambers, Ferguson, I,Iatt, Wa1Ias,

Adkins & f'uIler, P.A.

951 South Independence Roulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Jack Greenberg

James M.'Nabrit, IfI

Napeoleon B. Williams, Jr.

. 10 Columbus Cirile

New York, Nerv York 10019

Arthur J. Donaldson

Burke, Donaldson, Ilolshouser & Kererly

309 North Main Street

Salisbury, North Carolina 28144

'Attorney at Larv

Po,:t Office Box 3245

2O1 ftIest ]itarket Street

Greensboro, North Carolina 274A2

This the lpt day of Fe\ruary, 1982.