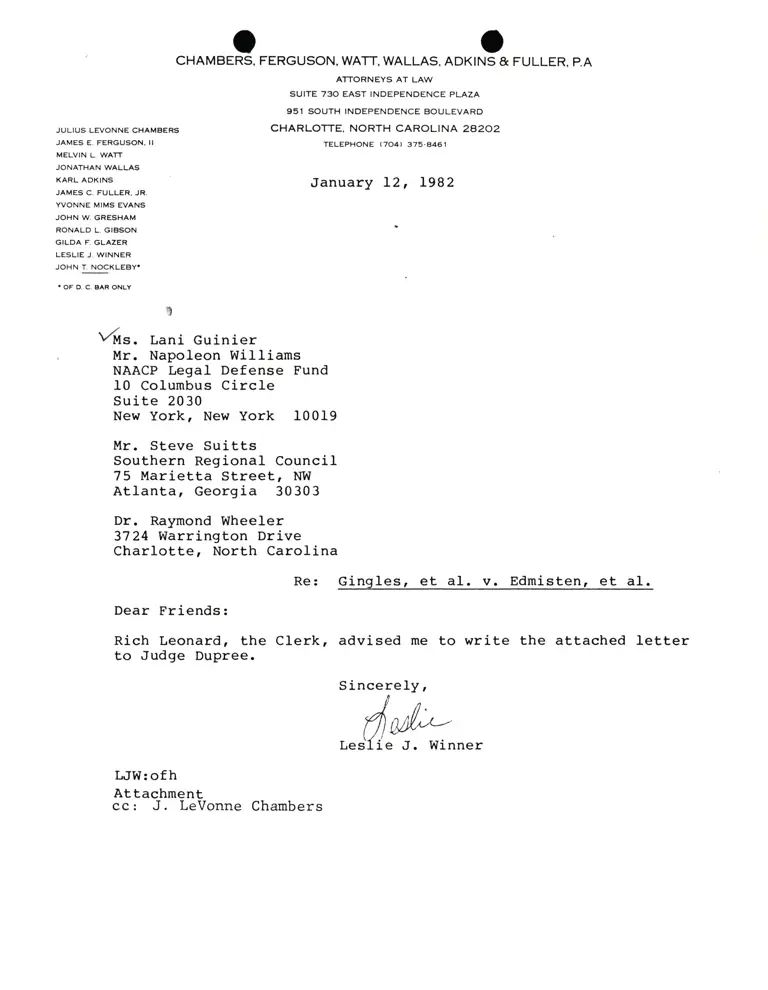

Correspondence from Winner to Guinier, Suitts, and Wheeler; from Winner to Dupree

Correspondence

January 11, 1982 - January 12, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Correspondence from Winner to Guinier, Suitts, and Wheeler; from Winner to Dupree, 1982. c9ccfeae-d792-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/54a4da1a-ee80-4d65-b312-afb890ae8835/correspondence-from-winner-to-guinier-suitts-and-wheeler-from-winner-to-dupree. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

o

CHAMBERS,

o

NS&FERGUSON. WATT. WALLAS. ADKI FULLER, P.A

ATTORNEYS AT LA\ru

SUITE 73O EAST INDEPENOENCE PLAZA

95T SOUTH INDEPENDENCE BOULEVARD

CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA 2A2O2

TELEPHONE (704) 375.8461

January 12, L982

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

JAMES E. FERGUSON. II

MELVIN L, WATT

JONATHAN WALLAS

KARL ADKINS

JAMES C, FULLER, JR.

YVONNE MIMS EVANS

JOHN W. GRESHAM

RONALO L. GIBSON

GILOA F. GLAZER

LESLIE J. WINNER

JOHN T, NOCKLEBY'

. OF O, C. BAR ONLY

Ytrls. Lani Guinier

Mr. Napoleon Williams

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Mr. Steve Suitts

Southern Regional Council

75 Marietta Street, NW

At1anta, Georgia 30303

Dr. Raymond Wheeler

3724 Warrington Drive

Charlotte, North Carolina

Re: Gingles, et al. v. Edmisten, et aI.

Dear Friends:

Rich Leonard, the Clerk, advised me to write the attached letter

to Judge Dupree.

Sincerely,

J. Winner

LJW: of h

Attachment

cc: J. LeVonne Chambers

CHAMBEQ, FERGUS.N, *ATT, *ALLAS, ADKI

o

NS&

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

JAMES E, FERGUSON. II

MELVIN L, WATT

JONATHAN WALLAS

KARL AOKINS

JAMES C. FULLER, JR.

YVONNE MIMS EVANS

JOHN W. GRESHAM

RONALO L. GIBSON

GILDA F. GLAZER

LESLIE J, WINNER

JOHN T, NOCKLEBY'

. OF O. C. BAR ONLY

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

SUITE 73O EAST INDEPENDENCE PLAZA

95I SOUTH INDEPENDENCE BOULEVARO

CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA 2A2O2

TELEPHONE t7041 375-A461

January 11, L982

Re: Gingles, €t

et al.; No.

FULLER, P.A

al. v. Edmisten,

81-803-CrV-5

-t

The Honorable Franklin T. Dupree, Jr.

United States District Judge

U.S. District Court, Eastern DisErict

PosE Office Box 27585

Raleigh, North Carolina 276LL

Dear Judge Dupree:

Gingles v. Edmisten is an action challenging the North Carolina

apportionment of both houses of the North Carolina General Assembly

and the North Carolina disEricts for the United States Congress.

Since the Supplement to the Complaint was filed on 19 November 1981

the following relevent events have occurred:

1. 0n 30 November 1981 the United States Department of Justice

entered an objection to Article II, 53(3) and 55(3) which prohibit

dividing counties in apportioning the General- Assembly.

2. On 7 December 1981 the United States Department of Justice

entered an objection to Chapter 894 of the Session Laws of 1981, the

Congressional Redistricting Act, and to Chapter 82L of the Session

Laws of 1981, the Senate Redistricting Act.

,

3. The state submitted its revised North Carolina House of

Representatives Redistrieting Act to the United States Department

of Justice, and the deadline for a response to that submi-ssion is

20 January L982.

Thus, unless the state appeals the Department of Justice rulings

to the United States District Court for the District of Columbia,

The Honorable Franklin T. Dupree, Jr.

January 11, L982

Page 2.

there are no enforcable Senate or Congressional reapportionments,

and we do not now know whether or not the House app6itionment wiit

be enforcable.

A-ccording to the best information available to the plaintiffs inthis action, the General Assembly plans to convene in special

session at the beginning of Februdty, L982 to enact new apportion-

ments and to postpone the date of the primary election fr6ir its

current date in t"tiy , L982.

)

The Court has set 19 February L982 as the date by which discovery

must be gompleted and by which the parEies shouid be ready for a

-pre-trial conference. However, dt this time it appears likely that

between now and then new apportionments will be enlcted. At ttristime it is, therefore, inefficient and wasteful of the time of thelegi-slators, the Court and the parties to proceed with discovery

on tlr. original apportionment acts or to have any hearing or trial

on the merits with regard to those acts.

r-, therefore, request that the court not schedule a hearing forthe three jduge panel or a final pre-trial conference untif it be-

comes aPparent whether or not the legislature will enact new appor-

tionment legislation and postpone the primary election. At thattime the Court will be able to set a schedulL which conforms totltu changes in the status of the apportionment legislation and inthe election schedule and which avoids unnecessary expenditures ofthe time of the Court and the parties.

Thank you for consideration of this matter.

'il;;ff

Attcrnei

ner

Plaintiffs

LJW: ddb

ccci J. Rich Leonard

James Wallace, Jr.

Jerris Leonard