Overton v. City of Austin Memorandum Opinion

Public Court Documents

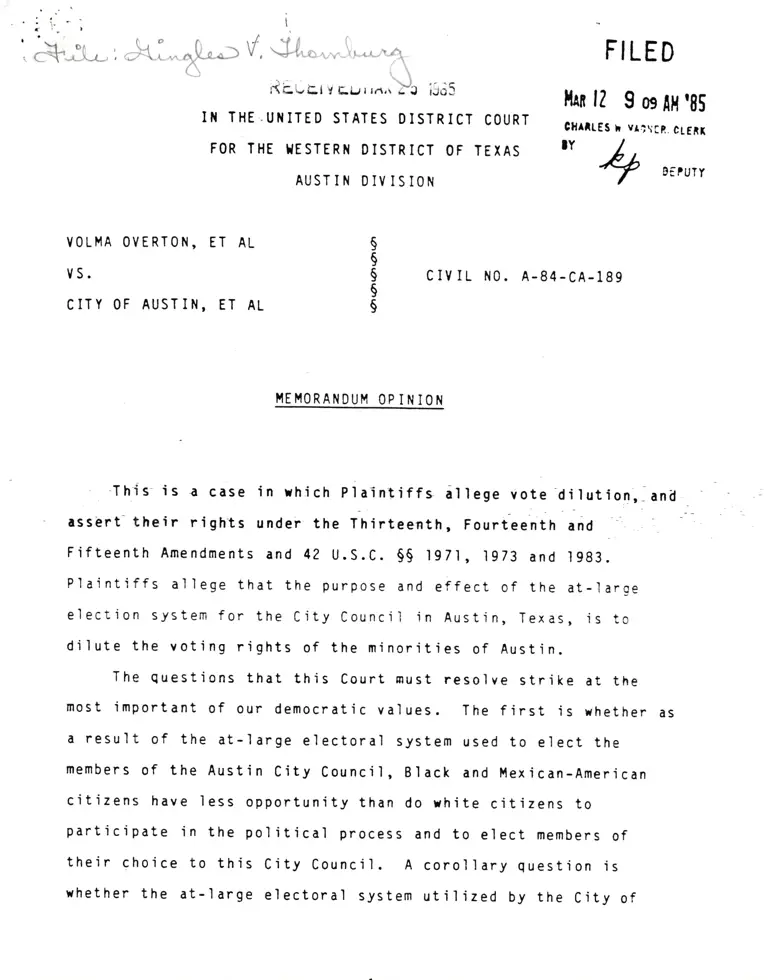

March 12, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Overton v. City of Austin Memorandum Opinion, 1985. 131089a0-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/54be6e11-fdbc-496d-b068-07ecbc5d5b7e/overton-v-city-of-austin-memorandum-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

,&;u:Ai: -it. ", ZLD

/. tU...,r'"r tr'-.\r^t FILED

xiurr Y Lur ra.i * ;Jo, J. ;ro5' r-'J' r^'r ' r rJo-!

lhn 12 9 os ffi t85

Iil THE.UilITED STATES DISTRICT C0URT sH^rrEsh vAi\rn.cLEir

FoR THE ITESTERil DISTRIcT oF TExAS !Y

AUSTIT{ DIVISION

sEIUTY

v0Lt'lA 0vERT0N, ET AL

vs.

CITY OF AUSTIN, ET AL

I,IE I,IORANDUI.l OP I N IO N

This- is a case in thict piaintif f s il lege vote di_lution,- anit

assErt- their rights under the Thirteeath, Fourteenth and

F i f teenth Ame ndments and 42 u. s. c. SS '19 7l , l9 73 and I 9g3.

Pla'i ntif f s a11ege that the purpose and ef f ect of the at-large

election system f or the city counci I 'i n Austin, Texas, .i s to

d'i lute the voting rights of the m'i norities of Aust.i n.

The questions that this Court must resolve strike at the

most important of our democratic va'l ues. The f irst is whether as

a result of the at-'l arge electoral system used to elect the

members of the Austin City Council, BIack and l,lexican-American

c'itizens have less opportunity than do rhite citizens to

participate in the po1 itical process and to elect members of

their qhoice to this City council. A corollary question .is

whether the at-l arge electoral system ut i I ized by the City of

s

$

5

s

$

c Iv IL N0. A-84-CA-189

Austin unlarfulry dirutes the voting strength of brack and

l{exican-American voters. Thus, the regar questions this court

must resorve are rhether the at-rarge erectorar system for city

council menbers viorates either the yoting Rights Act of I965,

42 U.S.C. 5 1973, dS amended in 1982 or the Thirteenth,

Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments of the united states

Constitution. 0bviously, other subordinate issues remain to be

resolved in the quest to make this determination.

It is incumbent on the Plaintif f s to estab'l ish that the

current system of erecting city counci r members vior ates the

united States Constitution. This task is onerous in settings of

much starker discrirnination. The burden has proven too difficult

for P'l aintiffs in this cause of action.

The Court rishes to pause for a moment to enunciate,rhat it

believes to be its role in this larsuit. This court will

ensure fidelity by the city of Austin to the one_manj one vote

pri nciple annunciated in Re.vnolds v. Sims,377 u.s. 5g3, g4 s.

ct. 1352 (.l964). The court has also carefully analyzed the

evidence to determine rhether the city of Austin has violated the

Voting Rights Act of I965, dS amended, or the.Constitutjon. It

is expressly not the role of th.i s court to determine rhat it

believes to be the best electoral system for the City of Austin.

That debate is better left for academicians, pol iticians, .od for

the body pol itic. This court must ansrer onry the questions of

constitutional ity and legal'ity of the current system.

Austin has a counci r-manager form of goyernment. The

present plan has six councir persons and one mayor, erected at

at

large. Each candidate must choose one of the six places (or

nayor) and rin the seat by a naJority of yotes.

The City of Austin is a municipa'l pol itica'l subdivision of

the State of rexas. It seryes as the capitol of the state, and

rhjle perhaps not as we'l I knorn as its sister cities, Houston and

Da1'l as, is a thiliving city located in central Texas. Accord.ing

to the '1980 decennia'l census, it has a population of more than

345,000. The ethnic composition Has approximate'ly 239,000

Ang'los, 42,000 Bl acks, and 65,000 ilexican-Americans. In

percentages, the round figures are l0 percent Anglo, L? percent

Black, and 13 percent ilexican-American. Austin, I ike most if not

a'l I Texas cities, Iacks a sterling record of minority invo'tvement

in the polit'ical affairs of the city. If one xere to take a

snapshot vier of historJ, and_that snapshot Has taken before the-_

1970's, I itt'le argument xould exist that mlnorit'iei suff ered f rom

discrimination. Yet, Austin in r985, ood the Austin of the past

fifteen years, has made progressive strides in m.i nority

representation and partic'i patjon. Indeed, th.i s Court takes

iudic'i al not'i ce of the order entered by the Honorable Jack

Roberts in a s'imil ar suit from 1917. Hernandez v. Friedman,

A-75-cA-229 and 0verton v . Ir ! edman, A-76- cA- ?zo. T he court

views L977 as a benchmark year for Austin. This Court f.irmly

believes that if the City of Austin is examined in terms of the

progress of the past fifteen years, rith spec'i a1 emphasis since

1977, the conclusion at whjch it must arrive is that the at-large

system violates none of Plaintiff's constitutional or statutory

rights.

a

The Court has attempted to avoid any nechanlcal analysls

that precludes common sense and the lntense Iocal appraisal

demanded by rhite v. Reqester, 412 u.s. 755, 769,93 s. ct. 2332,

2341 ( 1973). Rather the Court has intensely reviered the facts

presented as evidence in this case to determine whether, in its

overal I j udgment, based on the total i ty of the circumstances and

guided by the relevant factors of this case, the yoting strength

of minority voters is minimized or cancel led out.

The Plaintiffs tried to establ ish that tro (or presumably

more) Bl acks would better represent the Bl ack community than

rould only one. This Court refuses to equate the effectiveness

of a council member rith the color of his skin. The voting

R'i thts Act specif ical ly prohibits th js Court f rom requ'iring the

establishment o_f proportional repre-sentation-. .Fo. example, the

Plaintiffs sought to establish that lerry Dav-is,.'a Blaek attorney

rho has run f or city counci'l , is atypical of the Black society.

The Court cannot see the relevancy to this case of this effort

other than the most base paternal.ist.ic attituoe towards

minorities. Pla'i ntiff's efforts underscored the entire thrust of

its case; to establ i sh that to guarantee ef f ect'ive representation

of the m'i nority community, this court must guarantee that

minorities be elected and, inferentialty, that minorities be

el ected rho are acceptable to Pl a'i ntif f s. The Court can f j nd no

support f or these c'l aims in the Constitution.

The primary relevant factors are polarization,

unresponsiveness, and a tenuous state pol icy; and the close

correlation of these factors rith the ultimate issue of denial of

.t

minority access to the e'lectoral process.

reight than enhancing factors, such as the

requirement, thich are raci al ly neutral.

In finding an absence of intentiona'l discrimination, this

Court has examined a multitude of factors. These include the

adverse effects of past discrimination by the State of Texas and

c'ity governments on the exercise by minorities of their rights to

vote and access to participation in the pol itical system. The

Court has al so anal yzed the soc i oeconomi c st atus of mi nor i t i es i n

Austin, the amount of polarization, slating, the possible

tenuous ness of the pol i cy beh i nd the at- I arge system, and other

features that determine rhether the system as a whole has a

di scrimi natory effect.

The underlying f acts of this case _are rel_l documented in the

Fifth ciqcuit opinion of oye.ton ,. city o ,'.od In Re,'

0verton, 718 f .Za 941 (5th Cir. ). This Court ril.l delete the

facts unnecessary to render its opinion below.

0n April 5, .l984, prajntiffs volma 0verton, Iola Tay'lor and

John Hall filed the'i r compraint rith this court on behalf of

themselves, and al I other brack voters s jmilarly situated .in

Austin, Texas. The named Defendants rere the city of Austin, and

its Mayor and City Council members, both in their individual and

offic'i al capacities. Plaintiffs based the case on the broadest

of c'l aims ( i. e. 'this is a proceeding to vindicate the rights of

Black citizens of Austin, Texas, to participate in the pol itical

pr0cess on an egual basis, to which they are presently denied jn

the at-lar9e manner of electing the city council of Austin,).

They are due nore

naJorl ty yote

5

tt

P I ai nt i ffs requested that the Court des i gnate them as a cl ass,

and that as a class, Black voters are less than l?/ of the

electorate. Plaintiffs alleged that the at-large system of

electing City Counci'l members in Austin 'is not equal ly open to

participation by B'l ack citizens, in that they have less

opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate

in the pol itical process and e'l ect representatives of their

choice.ol plaintiffs base their claim on the Thirteenth,

Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the united States

constitution. The civ i I Rights Act of '1856, '1871 and 19G4,

42 U.S.C. SS l98l and 1983, ird the Voting Rights Act of t9G5,

42 U.S.C. S .l973, €t seq., dS amended. The complaint thus

al leges both unconstitutional intentional racial discrinination

and unlarful dilution of the voting strength of Blacks.

Plaintiffs sought to have this Court-(1)- declare this

matter to be a cl ass action, (Z) decl are that the present

at-1arge system is unconstitutional and/oli 11ega1 under the

Unjted States Const'itution and the Voting R'ights Act of .l965,

ds

amended; (3) adopt and institute a new pl an that remedies this

viol at'i on of their rights; and (4) enjoin an.y f urther elections

10ften at the hearing, it appeared to the Court that by ,,of

their cho'i ce' Pl aintif f s t6ant "bf their race. o This Court-wi ilnot be so patroni z'i ng to any ethni c group as to suggest that on'l y

persons of their own skin color can legal 1y serve their'interests.

from taking p'l ace under

sought no preliminary I

the present at-l arge

nJunctive relief .?

the Bl ack Citizenrs

pl an. The comp I a i nt

0n April 12, 1984, Task Force ( BCTF )

moved thi s Court to i ntervene as Def endants. The BCTF c'l aimed to

represent interests of Bl acks in Austin, but with the be'l .i ef that

the current at-large system was not unconstitutional or unlawful.

Indeed, the BCTF c'l aimed that the dif f erent system bei ng proposed

(single-member districts) would dilute the votes of Blacks. The

Court f irst a'l lored the BCTF in as amicus curiae, pitther than as

intervenors (order dated July ZS, l984).

The Defendants filed their ansuer on April zg, .l994, denying

that the at-large system of electing the six council members and

one mayor denied or abridged any of p'l aintjff's rights under

eithe_r the United States Constitu-tion or_ the Yoting Rights Act.

Defendants -also denied any diserimio.io.y intent on the part of.,

the City.

0n ApriI 30,1984, Plaintjffs filed their First Amended

complaint. Ljttle was altered from the original complaint,

except that the cl ass action al legations tere omitted and the

Austin branch of the NAACP was added as a party plaintiff. 0ther

than the request for cl ass status, plaintjffs stil I sought

essenti a1ly the same re'l ief f rom this Court.

Pl aintiffs and Defendants each fi led an objection to the

I'totion of the BcTF to intervene. 0n l,lay 11, 1994, the BCTF was

2Pla jntif f s f i led a motion requesting such 'i njunctive rel.iefon January 25, .l985.

Joined by'0orothy Turner, rnd Yelna Roberts, black cltizens of

Austinr'rho flled an amended srotion to lntervene as defendants.

This brought a response only from plaintiffs, rho fi led thelr

opposition on tlay 2L, 1984.

0n June 29, 1984, Ernesto ca'lderon, John !,loore, and Ernesto

Perales moved to intervene as Plaintiffs, individual ly and on

beha'lf of the cl ass of llex i can-Ameri cans regi stered to vote i n

Austin, Texas. They, too, al leged vioration of their

constitutional rights under the Voting Rights Act. p'l aintiffs

d'id not object to this intervention, and on July 23, 19g4, this

court entered an 0rder granting the motion to i ntervene.

0n July 31, 1984, the parties, acting in concert, f iled a

consent to dismissal without prejudice of the suit aga.inst the

mayor and counci I member defendants in their individual

capacities. -l{o notice of this dism.issal ras made to members of

the putative class nor did this Court approye of the dismissal.

The parties, again acting in concert, then fi'led a oJoint

l'lotion for Interim 0rder" on August 3, .l9g4. The court took no

act'i on on th'i s l,!otion. It would advance the bal I l.i ttle to

recount the next few chapters in deta'il. In short, the Court did

not s'ign this proffered 0rder, precip.itating an appeal to the

F'if th circuit by al I parties then in the suit. The Fif th

circuit, after oral hearing, denied the rrit of mandamus and

returned the case to this District court. This court then

al I owed i ntervent i on by lrtark Spaeth and the BCTF i n 0ecember,

.l984. The C'ity Counci I decided that the citizens of Aust jn would

be given the opportunity to vote on the change of the electoral

I

system as is proyided ln the crty charter and supported by the

Constitution and Statutes of the State of Texas (Tex. Const. art.

xI, S 5; Tex. Rev. clv. stat. Ann. arts.1185r 1170, vernon 1963,

Vernon Supp. 1984; City of Austin Charter art. II, $ l).

Th'i s election ras held on January I9, r9g5 and by a

fifty-three percent (531) margin, voters of the city of Austin

Yoted to retain the at-'l arge system. Reference in this 0pinion

to that vote may appear as voting on .proposition Five.,, A vote

for Proposition Five tas a vote for a change to a single member

district plan. proposition Five faired. This court set this

matter for non-jury tria'r for February 4, 19g5. The tria.l took

approximately one full reek to complete. The Court rishes to

note that al though the part i es, NAAcp, l{ALDE F, and the c.ity of

Austin had reached a settlement agreement and jointly appealed to

theFifthci..u]t,1tthetria]thereisnodispute.n..,.

attorneys fgr the City of Austin acted in a futly adversaria.l

fashion to the plaint.iffs.

Thus, this court has had the opportunity to hear the

testimony of those concerned and knowledgeable about the current

system of voting in Austin. It has also reviewed the myriad of

exhi bi ts i ntroduced by ar r of the part i es. The court i s we r r

aware of the responsibi I ity that it bears in th'i s case, ird that

the determination of rhether there has been a dilution of voting

strength or access is a question of fact that this Court alone

must resoJve.

9

The rost li.iklng aspect of Ithe erpert,sJ stuOy lsthat no other varl able than race or ethnlclty ieretested. In other rords, Ithe expert] dld not test forother .xp!anatory factors than race or ethnicity asintultlvely obvious as canplign expendltures, pirtyldentlflcation, lncoqq, media use neasured bi tost,rel igion, name identif ication, or dtstance tirat a

candidate I ived from any particul ar district. There

are rel l-established statistical methods, such asstep-rise multiple regressions, to test for therelative importance of such mult.iple factors.Signirlcaltly, the inference of b'loc voting from this

model builds on an assumption that race or nationalorigin is thg on'ly expl anation of the correspondence.It 'ignores the real ity that race or national' origi n may

mask a host of other exp'l anatory variables.

Jones, 730 F.2d at 235.

This Court bel ieves that pol arization is not simply rhen a

majority of all three srinorities do not vote for the same

candidate. This rras one of the definitions of polarization

offered by Plaintiffs.T -Rather, racia-l polarization is a

gattlln ln rhich Anglo voters consistentlf and p"edominantly rote

for only Anglo candldates, and minority voters consistently vote

for minority candidates. That is simply not the case in Aust.i n.

Although Plaint'i ff s are unw'i ll'i ng to give any reight to the f act

that minorities are elected to eyery official body in the Austin

7tn'is definition_Iequires the court to seek a utopia. It isunI ikely that one could envision any set of these groups:

environmental, gqI, business, ethnic, dorntorn, la5or, etc. whoagree on al I candidates al I of the time. Certiinly because amajority of a minority grgup does not alrays vote ior the rinningcandidates does not trans'l ate into a discriminatory impact onthat group or di lution of their ro'le. Additiona'l ly, tirls Courtnotes that the failure of ob!aining a consensus of Anglos, Blacksand l'lexican-Americans most often risult from the fact-thai gtacks

and l'lexican-Americans often disagree on their choice ofcandidates. In other rords, Anglos vote rith one or the other of

!h. gjnority groups more frequently than do the tro groups votetogether.

connunlty, thls Court rlll. Thls Court flnds ts a latter of fact

rnd as a ratter of Iar that the polarlzatlon that exlsts ln

Austin ls de minlmus, and ls lnsufficient to add any reight to

Plaintiff 's argument that the current system is lllegal or

unconstitutional.

Racial Appeals in Pol itical Campaiqns

An obvious component of Plaintiff's case is the use of

racial appeals in the course of politica'l campaigns. The Court

finds that the Plaintiffs failed to establish that any campaigns

in at least the last decade have made use of oyert racial themes.

As for implied or subliminal racial appea'l s, this Court is unable

to find credible evtdence to support thi s argument. Certainly

evidence ras offered. Dr. H{mmb-tstein, rho holds a Ph.D. in

Sociblogy, testifled as to'the racist appeals .present fn the -1985

referendun. His testimony ras pure sophistry. The Court,

presumably much I ike the television audience who saw the

commerci a'1 , was unable to detect the 'rhetorical rink. " The

Court must agree rith Defendants, that the'anti-Proposition 5'

canpaign (at least that part of it introduced into the record)

Iacked any appea'l to racist sentinent. The Court could perceive

no intent to create a racist theme, overtly or covertly. To the

contrary, ruch of the campaign ras directed against rhat the

sponsors perceived to be the negative results of the proposition

for Austin's minorities. The Court rejects i n Lo!o the testimony

of Dr. Himaelstein.

27

In .l982, congress amended section z of the yot.i ng Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C. $ 1973, to read as follows:

( a) No voting qual ification or prerequisite tovoting or stan9q.d, -pFactice, or procedure dr,ai t ueimposed or appl ied by any Stite or poiitical

subdiv'i sion in a manner which results.i n a denial or

l9.idgment of the right of any citizen of the UniteOStates to vote on aciount of iace or color,;.-in--contravention of the guarantees set forth in section'1973b(f)(2) of this title, as provided in subsection(b) of-this section.

The Court properly has Jurisdlction

the United States Constitution and under

amended.

Application of Sectjon 2

Thi s i s a cl aim under both the

and Section 2 of the Voting Rights A

this Court need not find intent and

suff icient. The test that this Cour

(b) A violation of (a) of this section isestab'l ished if , based on the total ity of _the

circ-umstances,. it is shorn_that the ioiitilir processeste3{j[s to nomination or election in'Ihe state-oi -

pol itfcal subdivision are not equat ly op.n ;;-par!icipation by members of a class 6r trtizensprolected by subsection (a) of this sectjon.i n that itsmembers have less opportunity than other members of theelectorate to participate in the poiit.i cal pro..ri anoto e]gc! ".presentat'ives of the'ir choice. The extentto which members of a protected cl ass have been electedto office in the State or political subdivisjon is one

over these cl aims under

42 u.s.c. s 1973, !S

United States Constitution

ct. P'l aintiffs stress that

impact, that ejther is

t is following is outl.i ned in

circumstance which may be considered: provided. Thatnothing in this section establ ishes a FT-gT-r-E'nave

members of a protected cr ass el ected .i n iumbers equarto their proportion in the population.

the Senate Report to the Act:

P I ai nt I ffs nust ei ther prove such i ntent, or,altellatlvely, nust shor that the char renged system orpractice, in the context of all the clrcumstanles inthe Jurisdiction ln guestion, r€surts in ninorities

bei ng denied egual access to-the por ltical p.ocesi.

Thus, the test to be appl i ed i s a test and in the context

of the tota'l ity of c jrcumstances.

The f undamenta'l purpose of the amendment to Sect i on Z tas to

remoYe intent as a necessary element of racial vote di'l ution

cl aims brought under the statute. Congress accompl ished this by

codifying in the amended statute the racial vote di'l ution

principles applied by the Supreme Court in t{hite v. Reqester, 4lz

U.S. 755, 93 S. Ct. 2332 ('1973). If the result, irrespective of

the intent,

-when assessed in 'the totality of circumstances,,, is

to cancel out or minimize the voting strength of racial groups,

then the electoral systefi-is illegal. The l{hite v. Reqester

racia'l vote dilution principles, as assumed by tfre Congress, rere

made explicit in ner subsection (b) of Section 2 in the proyision

that such a 'resu1t," hence a vioration of secured voting rights,

could be establ'ished by proof based on the totality of

circumstances that the pol itical processes leading to nominat.ion

or election are not equally open to participation by nembers o1'

protected ninorities.

congress mandated that courts should consider the

interaction of the chal lenged electoral system xith the

historical, soc'i a1, and pol itica'l f actors general ly submitted as

probat'ive of dilution to determine rhether 'based on the total ity

of c'i rcumstances' the challenged electoral system does result in

racial vote dilution. Section 2(b) exp'l icitly perm'i ts this Court

resu'l ts

to conslder ln lts rnalysls.It]he extent to rhich nembers of a

protected class have been elected..

If Congress had lntended that nunicipal ities ln al I cases be

required to have an election system ln rhich proportional

representation is based on discernable minority bodies, perhaps

it could have. It rise'ty chose not to do so. It expl icitly

provided to the contrary.

As a guide in its analysis of this case, the court has

turned to the Senate Report on Section z. The senate Report

g i v es part i cu I ar approv al to

aff'd per curi am sub nom. , E ast Carrol I Parish School Bd. v.

tu,f arshal I , 424 u.s. 536, 96 s. ct. tog3 ( lg76). The senate

Zimmer v. l{cKeithen, 495 F.Zd

has el aborated on thi s I i st of

reighed under a totality of the

the j ur i sprudence deve I oped i n

LZ}T (5th Cir. I973) (en banc),

Report

betypical faetgrs that _are to

c i rcums tances approach. -

Typ'ica'l factors include:

1. the extent of any history of offjci aldiscrimination in the staie or poiiticar subdivis.i onthat touched tl. r i ght of the members of the mi nor itygroup to reqister, to vote, oF otherwise to participatein the demoiratic pro..ri;

?- the extent to which voting in the elections ofthe state or por iticar subdivrsron"is raciairipolarized;

3- the extent to rhich the state or po1 iticalsubdivision has used unusua'r ry i..;;-;rectiondistricts, majority vote "eqri.ergiir, anti-irngte shot

Ployisions, or other voting practicei'o. proceduresthat nav enhance !he opporiuiriti f;;-aisciiminiiro,against the minority gi.bup;4. if there is i cahaiaate slating process,rhether the members of the mino.rIy-i;;rp have beendenied access to that process;

5. the extent to which members of the minority9!oup in the state or politicar subdi;rsion u.;; i;leffects of discrirnination in such are.t as education,

emplgyment rnq health, rhich hinder thelr abi I lty toparticipate effectlvely ln the pol itical process;

5. rhether poI ltical campaigns have been

characterized by overt or subtle raci al appeal s;7. the extent to rhlch nembers of the minority

group have been elected to public office ln the

Jurisdiction.

'Add i t i onal factors that i n some cases have hadprobative value as part of plaintiffs, evidence to

establ ish a violation are:

whether there is a significant Iack of

responsiveness on the part of elected

of f i ci al s to the particu'l arized needs of

the members of the minority group.

rhether the policy underlying the

state or pol itical subdivision,s use of

such voting qual ification, prerequisite to

voti ng, or standard, practice or procedure

i s tenuous.rl{hether these enumerated f actors wi I I

often be the most relevant ones in some

cases other f actors ri'l I be i nd i cat i ve ofthe alleged dilution..

1982 Senate Report at 28-29 (footnotes omitted

Code Cong. & Admin. lters 1982, pp. ?06-?07. L

Senate Report, re do not preclude the possibil

f actors -other t.han those enumerated i n Iimmer

rel ev ant i n an appropr i ate case.

Hi story of 0ffici al Di scrimi nation

The at-lar9e election system xas implemented in Austin in

elected at large on the1909. It ras a five nember council,

basis of a plurality. The mayoral position uas then filled by an

election from within the five sitting council members. To

prove that a Constitutional viol ation exists, Pl aintiffs must

establ i sh that the system was imp'lemented rith the purpose to

discriminate against minorities. Plaintiffs attempt to

). u.s.

ike the

i ty that

nay be

accompl jsh this by focusing on the adoption, 'in .l953, 0f a

naJorlty requlrement and also the requlrement of a cholce of

place. Some evldence ras lntroduced that the purpose of thls

change was the near vlctory of a Black candidate for city

council.4 rhile this question may be of some interest to

debate, the Court chooses to examine this. change in light of the

test enunciated in itqcartr_yr-_!g-:gn, 749 F.?d 1134 (5th cir.

lg84).

The pertinent Ianguage is'the plaintiffs must proye that

the at-l arge election pl an has a discrininatory impact upon their

voting strength and that the system ras implemented or maintained

rith the intent to discriminate." Id. at 1136. llhile the intent

of the implementation may be a matter of debate, this Court is

without doubt that it has not been maintained rith the intent of

discrimination, nor has it had that result

meet their burden of proof on- either prong

The Court rill go further.

Plaintiffs fail to

of_ i mp ac t or pur!os e .-

This Court is amply persuaded by Defendants that plaintiffs

fai led to establ ish, tS Has thejr burden, that the .l953 Charter

change was the resu'lt of discriminatory intent. Plaintiffs rest

their argument on the thinnest of reeds as they impute

discriminatory intent to f acts that are essential'ly benign. If

the case of Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F.Zd 364 (5th Cir.

1984 ) is to be the standard thi s court nust fol I or, then

4Tne City Council ras enlarged in 1967 by amendment to the

!ity charter to consist of six council members. In r969, the

Charter ras again amended to provide for the separate el6ction of

!-m?y9l:- Apparently, neither of these steps are chal lenged byPlaintiffs.

.'t

Plalntiffs rproof'of dlscriminatory lntent becomes even rore

gossrner. Plaintlffs rould ask thls court to lmpute

dlscrininatory intent or notive to the entire Austln electorate

based squarely on the fact that a Black candldate ras eighth of

fourteen candidates for Counci I office in I951. The Court finds

that it is pure folly that a major and radical change in the

entire electoral system ras a reaction to the candidacy of a

Black man rho ran for office. The Court has reviered the

exhibits that Plaintiffs submitted from that time period, but the

Court believes these do not reveal the entire landscape against

rhich the changes'rere made. The Court finds that plaintiff,s

facts pale against rhat actual ly occurred in .l953.

As

estab'l ished by P'l aintiffs themselves, a fifteen member committee

had been created to propose changes in the City Charter. The

amendmentsIerethepro.ductof.ayearl-ongs!u.dyby.this

conmittee. The conmittee inciuded representatives of the

minority communities. The propositions that rere voted on that

day amount to a complete oyerhaul of the structure of the city

g0vernment. Indeed, there rere more than thirty separate

propositions to be considered. Issues involved the power of the

city llanag€r, eligibility requirements for candidates, and the

use of I imited purpose annexation. Having reviewed aI I of the

changes that rere suggested by the committee and adopted by the

city electorate, it is equally plausible for the court to find

that the changes rere benign, or indeed rere for the purpose of

enhancing minority participation in the electoral system. The

Court is not suggesting that Austin in 1953 xas a full year ahead

l5

of the supreme court's Brorn v. Board of Educatron,347 u.s.4g3,

74 S. Ct. 686 (I954) decislon ln lts move torard an integrated

pol itical system. Rather, the Court ls demonstratlng the paucity

of proof by Plaintiffs that the shift to place elections and a

majority vote system lere motivated by discriminatory intent.

As to the change in the Charter in 1953, plaintiff failed to

estab'l ish many key elements. There is I ittle or insuf f icient

credible evidence about any racial tension that may have existed

in 1953. It is only conjecture that it was rell known at the

time that the change to prace and majority requirements rourd

dilute minority voting porer. There is an absence of evidence

that supporters of the Charter amendments or the medi a emphas ized

the potentia'l dilution aspects of the change. The court notes

that the city did-n_ot also _adopt staggered terms or other

p0tgnti al ly vote di l uting f eatures. . rn. the lg53 charter, --

.

AmendmenL election, Proposition 5, rhich accompl ished the change

to place elections, also effected other changes including setting

the date for el ect ions on the first saturday in Apri 1, lowering

the res idence requirement for counci lmen from five years to three

years, and eliminating the requirement for a petition of 25

voters to accompany the filing of a candidate name. The court

specifically finds that the comments of Emma Long during the

campai gn rere i n reference to .mi nor i tyr i n the abstract

pol itical theory sense rather than in a racial sense.

Legislative bodies rourd become paralyzed if courts rere

able to intervene in their por itica'r process by ascribing some

sinister motivation to the complex facts concerning an act now

three decades past. Had plalntlffs been able to c!rry thelr

burden of proof, thls court rould not hesltate to act ln the

fashlon dlctated by the Constltution. But the Court ls under no

r€quirement that it must abandon common sense or loglc in this

case. And logic compels it to view rith strict caution this

cl aim that the change in the electoral system ras implemented

rith the intent to discriminate. The Court therefore finds that

the Plaintiffs failed to carry their burden, !rd finds no such

intent on the part of the Defendant, the city of Austin, in its

change to a maJority at-large system, or in the change to place

elections.

Slatinq

The court f.inds that slating, if it exists at all;,fs such a

de minimus factor -as to be given but little reight in tha

*t.rtar rt clrcumstances. The reality is that Austin,s

po'l itica'l process dif f ers signif icantly f rom those d.i scussed in

Z'immer v. tlcKeithen, 48s F.zd rzgr, 1305 (5th cir. r973), aff ,d

, 424 u.S. 536 il976),

llhitcomb y. Chavis, 403 U.S. lZ4 (I97'l ) and Graves y. Barnes ,343

F- supp. 704, 726 (r{.D. Tex. tg7?). pl aintif f s f ai Ied to

estab'l ish that any group(s) exists in Austin that controls the

election of candidates through slating. certainly, nunerous

groups that endorse exist and are active.

slating involves the creation of a package or slate of

candidates, preceding fir ing, by an organization rith sufficient

strength to make the election merely a stamp of approval on the

cand I dates rl ready preorda i ned.

of any s I at I ng group.

Certalnly thls rould be the goal

slatlng groups create a bar rot of candidates and tr.y to

elect that slate as a package through financial and other support

for those select campaigns. In the cases in rhich sr ating has

been a factor in a court,s opinion, slating groups Iiterally

contro'l access of mi nor i t i es to be pl aced on the bal I ot. Thus,

sl ating in these cases directly determined rho the final

candidate rould be. This, of course, has a substantial effect on

the abi l ity of minorities, actuaily on ar r yoters, to elect the

candidate of his choice. This Court concurs rith Defendants that

the original and main concern of the courts that have addressed

the issue of'slating have focused on the access of minorities to

the primary and in turn to a general electio_n. plaintiffs

produ.go no eriJ.nce that L[ere are eny- r:qadb]oclrs to any ,..ron

of any ethniiity being on the uatiot for an.y .orn.il-s.;;.rb'

dv'

Further, it appears to the court that no group has the poriticar

p0Her or financial resources to control the election of a slate

of candidates.

It is unaYoidable that this Court focus for a moment on the

specific group that pl aintiffs, al lege conspire to create a

slate, the Austin progressive Coalition (ApC). p.l aintiffs have

subnitted no statistical evidence to this Court establ ishing the

percentage of Austin voters rho contribute time or labor to the

APC, rho are part of the APC, indeed rho are even arare that the

APC exrsts.5 They did not estabr ish that rerbers of nrnorrty

groups rere disallored rembershlp ln the Apc or that ninorlty

candidates Iere denied endorsements. To the contrary, of the six

council seats at least one Black and one llexican-American has

been endorsed by the Apc and erected by the voters in every

election since 1975. At least one Bl ack candidate ras endorsed

and elected in the l97l and 1973 elections. A second

[lexican-American, l'larcus DeLeon, tas endorsed but not elected in

I98'l .

l'linority candidates are endorsed by the Apc. The minority

community have agreed rith these choices. l{inority groups

participate in the APC endorsement process. This underscores the

fact that in Austin a plethora of endorsing groups exist, all of

which have their orn agenda they rish _to see effectuated. There

is nothing in th9 ev.idepce to estab-l ish t-hat the yal_ue or eff ect

of an ehdorsement by the Apc ir

t.ny

greater rhan that of the

NAAcP or the llexican-American Democrats, oF that the support of

any of these groups is pursued with any greater vigor than any

other endorsement. l{ithout exception, the evidence establ ished

that every candidate seeks the endorsements of every group he can.

There ras no evidence to establish either of the tro necessary

findings this court must make on this issue: first, that the

endorsement/s'r ating of any group is a poriticar necessity to a

5Therefore, whi I e

argument that the ApCplaces its impramatur

the Court wi I I accept for purposes of thi si s a powerf u I -endorsi ng groirp,' i [-i n-no rayon that as a fact.

ctndidate's success ln Austln and second, that nlnorltles are

denied access to these groups.

Thi s Court rishes to exhibit no brash naivete. Certalnly

groups exist that donate money, tine and energy to the e'tection

of candidates. The question before the court is rhether, in

Austin, a sl ating group of sufficient strength exists to preclude

meaningful access for minorities, oF di Iutes their voting

strength. candidates have run meaningful and successful

campaigns rithout the support of the groups submitted to this

Court as major slating groups. The Court bel ieves that the

process that occurs in Austin is one inherent in any political

process. Groups with specific aoa'ls are formed. These groups

analyze from among those rho are running xhich are (a) most

likely to succeed and (bl most l_ikely !q support that grouprs

lnterests._ !o a.rgtin cafipaig.l in r.ecent nemory has included the

issues of race or ethnicity. I-nstead, candidates have

establ ished agendas--priority issues--and the voters of Austin

are left to decide whom to eIect. Plaintiffs failed to establish

that any group in Austin has the power to control the u'ltimate

decision of vho is elected to the city counci l. No group

controls ultimate access to the ballot, either as a candidate or

as a Yoter.

The Court finds as

that under a total ity of

slating in Austin is de

implications.

a matter of fact and as a matter of I ar

ci rcumstances test the ex i stence of

minimus and has no constitutional

Polarlzatlon

The Ftfth Circult has noted that

'Ip]olarized voting as a precondition

claim." Jones, 727 F.Zd at 385 n.17.

eradicate race-conscious pol itics, not

indication of race-conscious pol itics

po'l arized voting.

A person does not have to be of a particular race to

adequately represent that race. The ul t imate goal of any

election system is for the election to be conducted rithout

regard or reflection to the race or ethnicity of the candidates.

This Court i-s unable to say such a goal has been fully achieved

in Austin, but the f ai lure to achieve this goal has no_t been

caused by the at-laige-system of voting. Ettrnicity and race are_ :-

not the main issue, o" eyen an obiious issue, in Austin city

pol it i cal races.

At the core of a racia'l dilution suit is

due to the interrel ationship and interaction

a trlal court nust find

of a votlng dilution

Section 2 is remedial, to

create them. The surest

i s a pattern of rac i al I y

issue of po'l arization

ally polarized vot'ing

ion case. Hcltlillan y.

the argument that

of invidious racia'l

This Court does not bel ieve that the

js 'i ndispensable, but recognizes that raci

rill ordinarily be the keystone of a dilut

Escambia County. F'I a., 748 F.Zd .l037, '1043 (5th Cir. 1984).

Plaintif f s f ailed to estab'l ish that rheneyer a minority

chal'lenged an Angto in city or other relevant races, a nrajority

of the Anglos rho voted rould consistently vote for the opponent

of the minority. Plaintiffs failed to prove that Austin voters

rere racially polarized.

pol trlzatlon cxhlblted ln votlng patterns tithin the chal lenged

electoral system, racl al mlnorlty groups rre effectively denled

p'olitlcal efficacy. Thus, vote dilution can occur

notli thstand i ng the absence of formal structural barr iers to the

e'lectoral f ranchise. .IT]he demonstrab'le unri I I ingness of

substant i al numbers of the raci al majori ty to vote for any

minority race candidate or an.y candidate identified rith minority

race interests is the I inchpin of vote dilution . . . ., Ginqles

v. Edmisten,590 F. Supp.345,355 (E.D.N.C. l9g4)

have fai led to establ ish this demonstrabte unri I I i

This court will adhere to the wise counsel of

Higginbotham rho wrote:

. Plaintiffs

ngness.

Judge

detailed f indingr_are-. required to support anycooctusions- pr. polarized voting.- iIe;i' iiiIln9, mustmake.tTlil lhat'they aia srppoiied'bi nore than theineyitable by-prgduct of a tbsing ca-naidaiy in .--lpredoninantly rhite voting populition. Failure to dos0 presents an unacceptable risk of reguiringproportional representation, contrary do coniressionalri I l.

Jones v- citv of Lubbock, 730 F.?d 233, ?34 (5th cir. I9g4).

This court is simply unable to make such concrete factual

findings to support any conclusions of polarized voting, due to

the reak evidence presented by Plaintiffs. Defendants strongly

contest, and the court thinks rightly So, both the methods and

conclusions of Plaintiff,s experts.

Dr. l,tiller displayed acute inability to give a coherent

definition to the phrase .acute polarization.' Indeed, his

testimony ras rife rith inconsistencies and mired in confusion.

Dr. I'liller's lnltial problem ls hls use of dlfferent neasures to

deternlne Bl ack and liexlcan-Anerican votlng strength. This ls

conpounded by his failure to take lnto account the difference ln

the population sizes of different precincts. This Court finds

that Dr. l{i I ler failed to establ ish any confidence intervals to

establ ish the value of his conclusion that one candidate ras

indeed the preferred candidate of a specific racial or ethnic

group. 0ften, under Dr. lliller,s statistlcal analysis,

candidates actual ly received negative percentages. lJhi Ie this

court understands the practical impossibility that statistics are

perfect, given the analytical deficiencies in this case, the

Court can give little reight to those elections determined by

small percen-tage differences for fear that they are in error.

Dr- !liller's analysls is replete rith a Ii-tany of other-errors.

.,r": Ilill.l dld-1ot .9igst..his data for variab.les such as

the educational or econonic composition of a precinct. He

dismissed this apparent reakness in his analysis by asserting

that there is no need to distinguish betreen .|lexican,,, .poor,,

and 'uneducated.' This Court strongly agrees rith Defendants,

assertions and views this broad statement as patronizing and

rithout factual basis in this case. Certainly plaintiffs have

established that the road to parity among all ethnic groups is

still to be fully travelled, a revelation that falls far short

of establ ishing that al I minorities are uneducated and poor. He

did not include in his analysis rhether the candidate was an

Ang'l o or a ninority, and of greater import, rhether the candidate

addressed mi nority concerns. Dr. t{i I ler chose to ignore that

.r)

non-ethnlc factors tre operatlng ln Austtn to effect the outcome

of el ectl ons.

The court turns to Dr. l,liller,s failure to establtsh a

confidence level for his regression analysis. Defendants

strong'l y dispute the accuracy of Dr. l,li'l ler,s methods here. l,luch

of this dispute centers around Dr. lliller,s use of an.r. factor

in his anaIJsis.6 An 'r, factor ls used by statisticians to

expl ain the proportion of variation in the votes a candidate

received that are accounted f or by the ethnic or raci a'l

. composition of a precinct. The higher the value, the higher the

degree of correlation of the results to the variable of

race/ethnicity in the precinct tested; this in turn potential ly

reflects polarization. Defendants cite Dr. I'liller,s analysis as

flared dqe to his failure to either -analyze thesq _yariables

'scpara_tely or to proceed to the squaring of his figures to

establ ish an accurate test of the confidence level of his

correl ation results. This Court be'l ieves that an analysis of the

races of the last ten to fifteen years reyeals that in many

contests the correJation coefficient is extremely Iow. Compare

this to the City of Lubbock case, in which the tota'l minority

population in the city was 26l (similar to Austin) and the values

of the correlation coefficients rere high. Jones v. city of

Lubbock, 727 F,?d at 368. The court agrees rith Defendants

i ts

( 5ttt

SFor an excel

problems, see

Cir. 1984).

lent analysis of the use of an oro value andJones v. C i ty of Lubbock, 730 F .Zd 233;

- Zii-

that Dr. lll I ler's 'homogenelty' expl anation did I rttle

to cure hts fallures ln analysls. certalnly homogenerty of a

racial/ethnlc group ls a factor that this Court conslders

important in deterrnining rhether an at-large system of voting has

a discriminatory impact or result. A high presence of

homogeneity rould militate against an at-large system. The lack

of hoarogeneity in economic conditions, education, employment, and

political philosophy tithin a racial/ethnic group rould suggest

that race/ethnicity is a lesser determinate of the decision made

in voting. The key consideration in polarization in an at-large

system is rhether Anglos vote as a bloc for only Anglo

candidates, i. e., xhether AngI os vote as a block based on

ethnicity.

There are many other sertous flars rith Dr. l,liller's

_-_anaIy_sis; He fa_Jled to distinguish betreen serious and token

candidates. He failed to determine rhether the candidate

emphasized a broad platform or ras a'one-issueu candidate. He

did not allow for the strong factor of incumbency. He failed to

determi ne rhether a candidate concentrated on speci fic

geographical areas of the City and rhether that candidate was

successful i n those areas. He did not bother to identify rhether

there ras an i ssue( s) that captured the entire debate i n that

particul ar election, and if So, rhether candidates tere elected

entirely on their position on that issue. The Court cannot avoid

being compel led to di sregard much of Dr. Hi'l ler's analysis under

the strong 1 o9 i c presented by Judge Hi ggi nbotham:

?q

Thls Court does not dlspute that Dr. Hlnmelstein belieyes

that the characters ln the coraerclal represented

llexicto:ADericans. Had Dr. Hilmelsteln gone beyond asking a

handful of biased people their opinion, the matter rould be

entirely different. Had Dr. Himmelstein conducted accepted

scientific analysis in the form of surveys to establ ish rhat the

aYerage Austin citizen viering the commercial thought about it,

this Court lould be rill ing to consider such evidence. Certainly

there is nothing in the record to establish Dr. Himmelstein as an

expert as to hor the average Austin citizen rould interpret the

message of the commerci al . The Court fi nds that pl aintiffs

rhol ly fai Ied to estabt ish that a racial appeal occurred in the

January 1985 campaign. The court is unarare of any other

- elections of the past trenty years that did involve racial-

appeal s.

Responsiveness

Pla'intiffs made much ado of the argument that minority

candidates are unable to properly respond to the needs of the

oinority connunity. Yet in their post-trial brief, they suggest

that responsiYeness is a factor to rhich this Court should give

but I ittle reight. The court disagrees rith both of these

arguments. The Court bel i eves the respons iveness component to be

a key element in its total ity of circumstances test. In this

regard, the Court finds the Austin City Council to be especially

attentive to the needs of ninorities in this city. A strong

argument can be made that an at-large system focuses pressure on

each councll nember to be responslve to the rlnorlty connunlty.

That nlnorlty councll nembers have felt unable to fully represent

the ninorlty communlty ls a factor to be relghed. Ihether thls

ras a Justtfied fear is a purely speculative natter as no

incumbent testified that he had rost ln a race due to placing

minority issues high on his agenda. Ilor did any ritness

adequately exp'l ain the lssues that they rould have been more

responsive to had they been elected from a district. llor is

there any evidence of the failure of municipal legisl ation

favorable to minorities due to the current electoral system.

This factor is further offset by the siinple reality that this

City Council has been responsive to the needs of the minority

community.

Ituch of the Plaintiff 's case !s premised on the argument

that East Austin is poor, and has r-emained poor due to the - .

neglect of the city council. Evidence of proverty in areas of

Austin, including the area of Austin east of Interstate 35, is

rithout dispute. Evidence of neglect of these areas due to the

minority popu'l ations that might exist there as it night relate to

an at-I arge system of counci I el ecti ons is unpersuas iye. Thi s

Court is unable to establ ish through-the evidence presented a

nexus betreen the at-l.rge systen of voting and the poverty of

these areas. Rather, this court is of the opinion that any

failure of the city council to react to the problems of the

ninority poPUlation is not due to the nrethod by rhich the council

members are eI ected.

Thls Court nust deternlne rhether the responslveness of the

councll ls lndtcatlve of preJudrce or raclal blas ln the

electoral system itself. This court flnds that plalntlffs falled

to establish a lack of responslveness to nlnority needs due to

the at-l arge system.

Pl aintiffs presented several ritnesses rho testified that

they, in a general sense, felt that the current City Council, and

Councils of the past, had been unresponsive to minority needs.

In the face of the great reight of the evidence to the contrary,

this ras insufficient. There is I ittle evidence that in the past

fifteen years the City Counci I has di sregarded mi nori ty issues,

or has in any ray fashioned their decisions on the ethnic

composition of the city to the detriment of the minority

commun-i-ty. _There las no evidence that the majority has -exploited

theiE pol itical status to the-detrinent of the minority. :- . --

It is not the "ot. of this Court to examine the actions of

the City Council and determine rhether-more or less money should

be budgeted for specific proposals, or rho should be hired to

fill emp'loynent positions. That is a'legislative function.

The Eleventh Circuit, in United States v. l,laranqo Countv

Conm'n, 731 F.2d 154G (llth Cir. l9g4), found that

unrespons iveness las substanti al Iy less important under a resul ts

test than under an intent test. I{. at lslz. This court

disagrees that unresponsiveness is of only linited importance

under section 2. The circuit court rrites that'section 2

protects the access of minorities not simply to the fruits of

government but to participation in the process itseIf.. Id. at

L572' But evldence that clected offlclals rre responslve to the

needs of nlnorltles ls evldence that has a bearlng on the lssue

of:hether nlnorlties are excluded from polltical partlclpatlon.

It should not be so neatly dlvlded out as a separate genus of

evidence. Evidence that elected officials ignored minority

issues rould certainly reflect that minority participation of any

amount ras neaningless, and therefore impacted by the system. It

ls not a yery bord statement for this court to make that the

inverse is also true. strong evidence of responsiveness ri I I be

directly consldered by this Court as to rhether ninorities are ln

fact excl uded from the por iticar process. The court ri r r

'compare' evidence of responsiveness to evidence of excl usion.

Second,-the learned panel of the Eleventh Circuit rrites

th-at 'res-ponsiveness is-a- highry subjective natter, and this-

subjectivityisatoddsritht-heemphasisofSection.2]on----

obiective factors.' This Court disagrees. Responsiveness is no

more'subjective'than the other factors that this court must

consider. rhether there is polarization, for example, is a

subjective test based on objective factors. yet the

responsiveness lssue is on'ty t_IUiective in that this Court must

analyze aggregate objective data and nake a decision that the

city has or has not been responsiye. That is the role of the

trial court in these cases. Fault lies in the use of a

'subiectiYe'analysis only if this Court considers inadeguate

objective evidence to nake a proper decision, or makes an

improper decision based on the objective evidence admitted.

Thus thls court can flnd no basrs rn logrc to rgree that

'although a shollng of unresponslveness ntght have some probatlve

value a shorlng of responslveness rould have yery llttIe.. Id.

at L572. Thls Court believe that a shoring of either should be

given probative value under a test that ls as broad as a

'total ity of circumstances,' test. This Court finds no sol id

evidence of unresponsiveness on the part of the City Counci I

Rather, this court finds the Defendants have clearly been

responsive. The Court finds that the evidence of responsiveness

reighs predominately in favor of a finding of the

const i tut i onal i ty of the current system.

There is some dispute o_ver rhether. tenuo-usnqss

-

is -itserf_ a-_

primary factor for-the court to co_nsider. The,court

the implementation of the mliority vote and pl ace reguirements

exhibited a discriminatory intent. Tenuousness requires a

slightly different but related standard. The question becomes

rhether the original iustification for instituting the system

Tenuousness

to be tenuous. There is no state pol icy against at-large

Plaintiffs failed to establ ish that the lmplenentation of

the system ras tenuous.

appear s

systems.

lg73).

llor is this

the at-large and

Court conyinced that the reasons

pl ace requ i rements are tenuous.

in Austin each tine the issue of

for maintaining

Unl ike the City

single memberof Terrel I case,

dlstrlcts has been placed on the ballot, lt has falled. The nost

recent electlon ras on January l9r lg8s. The electlon rrose

prinarlly as a result of thls I ltlgatlon. The only lnpact of

these elections ln the Court's conslderation ls to demonstrate

that there have been no questionable manipul ations of the

election process as.may have occurred in city of rerrell.

In deternining the tenuousness issue, this court has

reviered the evldence concerning the distrlbution of the several

ethnic groups throughout the city. The at-r arge system arguably

benefits the minority community of Austin, rhich is substanti aI ly

dispersed throughout the City. Defendants presented credible

evidence that the at-large system enhances ninority access. It

is rell-estab'l ished that rhen an at-large system actually seryes

a strong goye_rnment p_o'l icy rholly divorced from m_aintena0ce of

racial discr:imination, it is not unconstiiution-al. ila'intiffs.

have failed to....y their burden that the at-large system is

tenuous. The court fi nds that Aust in's pol icy reasons for

mai ntai ni ng an at-l arge system are not tenuous.

The Kirksey Analysis

The Court has carefully reviered this case in light of the

case of Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.zd 139 (5th Cir.

1977) (en banc), cert. denied,434 u.s.9Gg, gg s. ct. s12 (lgll)

The Court i n K i rksey rr i tes fi rst that:

Io]nce Plaintiffs establ ished a past record of racialdiscrinination and official unresponsiveness rhichrequired the concl us i on that at I east unti I a short

nunber of-19frs_past they had been denled equrl rccessto tlre polltlcal processes of the county, tt-ihen-aaiito the Defendants to come forrard rith Lvtoence thatenough of the lncldent: qf !tg past had been iemovid,

and the effects of past denial br access dlsslpat€d,that there tas presently eguallty of access.-

554 F.?d at 144-45.

This Court exp'l icitly f inds that Def endants have carried

their burden to establish that there is currently equality of

access. The court also finds that ninorities have had equal

access to the e'lection system for the past tro decades. This is

reflected by the fact that minorities have voted for candidates,

run for office, and been elected to office ln aIl of the relevant

pol itical offices.

In Kir\sey, the court next rrote .Ii]t is not necessary in

any case that a minorlty proye such a causal link. Inequality of

access is an inference rhich flors fronr the-existghce of economic

and educational lnequari'ties.' Kirksey i, Bbaid of supbriisors,

554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir. l97tr.

this by rriting that:

The Eleventh Circuit tras expanded

llaranqo County, l3l F.2d at 1569.

l{o system is invulnerable to this standard. ilo system in

Texas is completely free from the taint of discrimination. It is

saf e to say disparity exists socioeconomica'l ly betreen Anglos and

minorities in most if not aIl cities. The Court believes that

rhen there is clear evidence of present socioeconomicgf political disadvantage resulting from pastdiscrinination, . . r, Itre burden is not bn theplaintiffs to.proye that this disadvantage is iausingreduced pol itical participation, but ratFer is on-thoserho dg4y the causal nexus to shor that the cause issomething else.

the latter fact rs rndeed r result, at reast to some degree, of

the former fact' llo Defendant can concelvably overcone such a

burden' The burden of proof can be transrated rnto a frndrng

that the current system, rhatever the current system rs,

unconstitutionaily dirutes or reduces po'r iticar participation.

Thus, the city is cast rn the position of having to pi.y, much in

the fashion of original sin.

This court berieves rt is proper to vrer the current

socioecononic status of ninorities in terms of rhether it is

increasing in relative terms to its orn past. Then the court

should analyze the interrel ation that can be empirical ly proven

between the electoral process and the socioeconomic levels of

minorities- Betreen'tg7o and I9g0, Dinorities have inproved

t!.ir gene_raI conditions at a. r:ate gIe-ater -than the total

population has lmp,:oved; From l97O to 1g€0,, .Blick family nedian

income increased nore exprosivery than the median of the city of

Austin. In r980,4g percent of the Brack population resided in

census tracts rhere household median incomes rere g0 percent or

greater of the city househord nredian. Trenty percent of the

Black popu'lation resided in census tracts rhose household nedi an

incomes uere greater than the city nedian.

0f unl inited inportance in this analysis are the statistics

involving the increasing nobir ity of Austin minorities.

Traditionar 'East Aust in' is decr ining in the percentage of the

total Black popuration in Austin rho reside there, and ar.r other

areas of Aust in are increas ing their percentage of the total

Black popuration. The dispersion pattern for Hispanics is even

rore dramatic. In 1980, G€nsus tracts that tere naJorlty Black

rccounted for less than half of the total glack populatlon ln

Austln. llaJorlty Hlspanlc census tracts account for only 30

percent of Austin's Hispanic popul ation; thus , l0 percent of

Hispanics I ive elserhere in Austln. Ilhen these minority

dispersion patterns are cons idered, the at-large system ls shown

to be particularly beneficia'l to the dlspersed members of the

ninority' rho it must be remembered nor account for more than

half of the minority Popu I ation. Therefore, the effectiveness of

a ninority population that is nor largely dispersed is maximized

in terms of representational access under the existing at-l arge

system.

The third criteria of Kirksey involves rhether any past lack

of access has been amel iorated -in the_present. The Court finds

abundant gyldence from Defen-dants -that this has occurred. The

Court must note that Pl aintiffs have not al leged that Bl ack

residents register to vote in a lorer proportion than do Anglos.

The Court finds no credible empirica'l evidence to support an

allegation that Black voter turnout is proportionately less than

Angl o voter turnout.

Dr. cervantes testified for plaintiffs that there is a

disparity betreen proportion of Hispanic popul atlon ( lg percent)

and percentage of Hispanic regi stered voters (9.5 percent) .

Dr. Cervantes testified that there are three factors that reduce

this apparent disparity. They are: (1) a greater percentage of

l'lexican-Americans be'low voting age than in other ethnic groups;

(2) differences in the ray llexican-American population records

tre kept by the Secretary of State of Texas (by Spanlsh surname)

and the Unlted States Census Departnent (by Spanlsh orlgln)

resulting tn census oYerstatenents of about l5 to ZO percent rhen

coirpared to spanlsh surname voter reglstratlon flgures; and (3)

the presence of a significant al ien population rhich also causes

the census f igures to be overstated compared to registered voters

rho nust be citizens. Due to these possibre reductions, it is

not Possible fron the evldence adduced at trial to determine rhat

the actual disparity is betreen the llexican-Amerlcan proportion

of popu I at i on and the proport i on of regi stered yoters.

Plaintiffs failed to carry their burden of proof on this issue.

The At-Larqe Requ i rement

Some.courtshive.triateda.nat;Iarge.".guirementas

virtual ly an unionstitutional requirement per se.

rritten that the najority vote requirement:

It has been

requires a run-off el ection between the tro candidatesrith the most votes if no candidaie reieires-; ;;i6.iiyin the first election. The run-off al lors rhita-;;tersrho scattered their votes among various rhitecandidates in the first electi6n to ionsol idate theirvotes in the second to defeat a ninority candiJati-r'i,oreceived a plural ity of the vote in the Host eleciion.

l{ote, RaciaI vote Di'rution in t{ultimember Districts. The

, 76 llich. L.

Rev- 694,697 (1978). The court has found no evidence of such a

pernicious use of the at-l arge system in Austin. certainly the

court accepts that an at-l arge system could have this resu.lt.

Constitutional Standard after lJashinqton v. Davis

Yet thls court expressry flnds that the plalntlffs have

conpletely falled to establ lsh that the at-lrrge systen ln Austin

has had th I s resu I t. An at- I rrge systern can exacerbate a

polarized poltty; but, rrthout proof that the naJority

requirement does enhance a system already fraught rith

discriminatory impact or intent, the at-Iarge reguirement in and

of itself holds no evi l.

CI ass Action

This Court finds that there is no need to certify IIALDEF or

LULAC as representing a class. Of necessity this decision rill

affect all voters living in the city of Austin. This suit ras

extremely rel I publ icrzed throughout the city. The granting or

denial of 9er]if-icatfo.n h-as--no effect in this case. Eyery party

rho sdught adniss-ibn to-this. case las adnitted. The Court finds

that Plaintiffs adequately represented al I persons rho bel ieve

that the current system is unconstitutional or unl arful. There

ras' in effect, no ray to opt out of this suit. This Court fjnds

that no benef it lou'ld be obtained by certif ication of any cl ass

i n th i s cause of tct i on.

Attorneys Fees

-

Defendants have not requested attorneys fees. t{onetheless,

the Court has considered the propriety of such an arard in this

case ' Attorney's fees are to be awarded to preyai I i ng Defendants

rhen Plaintiffs' suit is frivorous. christiansburs Garment

ComPanY Y.8.8.0.C. , {34 U.S. 1l?, a?L, gg s. ct. 694, 700 fig7g).

This Court agrees rlth the panel ln

725 F.?d 1017 (5th Clr. 1984), that

to Defendants rould have a chilling

constitutional violations that might

at I 023. Therefore, th i s Court ri I I

the enter i ng of th i s 0p i n i on for the

Defendants.

Yelasguez v. Clty of Abilene,

Findinqs of Fact

1. The city of Austin is located in Travis county, Texas, a

Central Texas County. Austin population, according to the lggo

decennial census, is 345,496.

2.- 0f this lgSotpoprlation, 64,166 or Igr of the city,,:_ --

totai poputation is of spani-sh or ilexlcan-American origin.

3. The I98O census states the Bl ack popul ation as 4Z, ll8 or

12.21 of the City of Austin,s total population.

4. There exist in the city of Austin geographicalty

identifiable areas of high concentration of minority population.

Specifically, these areas are census tracts g.01,9.02,10,

13.06, and 23.09 rhich contain a llexican-American population of

50r or greater; and census tracts 4.02,8.02,8.03,9.04r 9.01,

21.09, 2l-10, 22.0L, 22.02, and 22.02 rhich contain 50r or

greater BIack population.

5. Census tracts 4.02, 8.02, 8.03, 9.04, 9.01, 9.02, 10,

21. 09 ' 2L - 10, 21. 11, 22.0L, ??.02, and 23.09 conta i n lsl or

greater ni nor i ty popu I at i on.

the rrard of attorneys, fees

effect on sults to redress

be undesirable. 7ZS F.Zd

not entertain a motion after

arard of, attorneys fees for

6. Austln clty councl r erectlons currently Gncompass

clty-rlde votlng, knorn as at-Iarge electlons. Thls systen ras

adopted ln 1953r ?€Placlng a system ln rhlch councll elections

rere conducted through an at-large plurallty electoral system.

Currently' persons running for City Council ln Austin must run in

one of six places (excluding the maJor,s seat) and receive a

majority of votes from the voters at-Iarge to rin the election in

that place. The Austin City Council consists of six councll

persons and one mayor. At the time of trial, all of its members

rere elected each odd-numbered year to serye for tro year terms.

7 - John Trevino, a lrexican-Amerrcan, rs the f irst

l{exican-American to be elected to the City Counci l. He

elected in T975 and has seryed sjnce that date through

present.

-

q-. gert Handcorl_ a Black, ras e'rected to the city council

in'1971; He ras the first BIack to be elected to the Austin City

Council. Since 1971, there has been at least one Black council

member serving in one of the six council seats. s

9. To measure to rhat extent minorities are participating

in the pol itical system, Defendants compared the minority group,s

proport i onal presence I n the popu I at i on to that group's

proportion of representation on the city counci l. The nethod

used ras a subtraction method and the result ras labelled the

sPlaintiffs invite this Court find that this constant tenurebv 1. B'l !ck, as rel I as the f ive term ienure of a t{eiiian-Ameii.inon the Council is nothing nore than the rhim of an Anglo induced

'ggnt l eman' s agreement. '- The Court ri l l now,

-

ana thr6u!noui-tIisopinion, decl ine that invitation.

tas

the

'ninorlty equlty score. r Defendants appl led this standard, rhich

ls extenslvely recognlzed ln the llterature relled on by experts

ln electoral demographics and nuniclpal government structures to

determine proportional representatlon. Black representation on

the City Council exceeds Black representation in the population

by 4.5 percent and Hispanic representation on the City Council is

belor the Hispanic portion of the population by ?.1 percent. The

conbined ninority equity score ras a positive 2.3 percent.

10- lli norities in Austin are represented in excess of their

proportional makeup of the population. This representation;as

higher than for any other city in Texas rith a population larger

than Austin's. Under the existing election system in Austin,

minorities have achieved proportiona'l representation not

gu?ranteed under either section z or the corstitutioR.

-- - 11.--since--I975, other than l,liguel- Guerrero, on-Iy three

minority candidates rho tere favored by a majority of their own

ethnic group have not been successful. Al I three were

l'lexican-Americans. None of the three received a majority of the

Black vote- Tro of the three received a larger percentage of the

Anglo vote than of the Black vote.

L2. A total of four candidates favored by at least one

ethnic minority rere not elected from 1975 to 19g3. In ten

races' minority candidates rho xere the choice of their racial or

ethnic comnunity were successful.

13. 0f the trenty-one (21) al'legedly polarized elections

since I975, only eight (8) of these elections involved a minority

candidate yersus an Anglo candidate. In tro of the elections,

the t975 general clectlon and the 1975 runoff electlon for place

5, the nlnorlty candldate ras successful. Of the remainlng six

'election3,.''the'nl'horlty connunltles spllt ln thelr support as to

four of the races. Thus, the loslng candldate ras not favored by

voters of one minority group.

14. The court is rell arare that even the history of

private discrimination in Austin should be considered tithin the

broad scope of the total ity of circumstances--that lt is relevant,

The Court further notes that the Plaintiff failed to establ ish

that rithin the past trenty years a record of private

discrimination against ninorities existed in Austin. As the

court has noted elsewhere in this 0pinion, the city has taken

effective steps (for example, the Fair Housing 0rdinance) to

ou_tlar discrininatory acts by pri-vate -citizens.

candidates f,or the City Counci I be residents of

geographic sub-di stricts.

that the at-l arge

particular

15. Plaintiff failed to establish the percentage of races

in rhich a candidate rho ron in the first election'lost in the

runoff. It follors that there ras no evidence presented of hor

often a minority candidate ron in the first election but then

Iost in the run-off ln real nunbers, or by eliminating

'non-serious'candidates (candidates rho received less than l0t

or 20/ of the entire vote), hor nany races included more than tro

candidates for that position. lJhen there are but tro candidates

for most positions, a maiority vote requirement is for practical

purposes no different from a pl ural ity vote reguirement.

17.

electlon

relative

18.

slnce the electlons are clty rlde, !Dd .at-l arg€r. the

distrlct nust be consldered to be.larger ln at least a

sense.

The clty llanager is Hispanic. The Senior Asslstant

City I'tanager is Black. 0f seyenteen appointments of assistant

city managers and department heads made by the city lrlanager,

seyen are Black or Hispanic, r€presenting rlll of the total.

19. A Black ras first elected to the City Council in I97l

and Blacks have served continuously on seyen different city

councils since 1971.9 These include ilr. Berl Handcox, l,lr.

Jinmy Snell and l{r. Charles Urdy.

20. A llexican-American, John Trevino ras first elected in

'1975, and is-currently serving in that of f ice. He is also

currently llayor Pro-Tem.

lZt. EYery Black and llexican-American elected to the Austin

city council has received a najority of votes cast by minority

voters.

?2. 0nIy one minority candidate rho has received the

majority vote of both the llexican-Americans and Bl acks has not

been successfu I .

23. The City of Austin has several Boards and Commissions.

In '1984-85, L6/ of the appointnents rere BI ack, and 11.5r rere

eTestirony and statistical evidence addressed adduced attrial Ievels that it is the_ greatest of fal l.ii.i-to beI iire thatboth mi nority groups ri I I aliays ag.ee on a candidate. As ri I rbe. ampl ified in.the 0pinion, ninority groups agreed rith eachother on a candidate less freguently- tIan iia ingio voters vithone or the other minority group.

llexlcan-Amerlcans. These flgures !re higher than those of

I 976 -77 .

24' The community Development commisslon has elght nembers.

currently, tro are Black and tro are r{exican-Americans.

25' The l{edical Assistance Program Advisory Board has seven

positions. Currently, tro Bl acks and one ilexican-American are

serving.

26. The Civil Service Commission has

appointed by the City l{anager. Currently,

llexican-American are on the Commission.

27' The Human Relations Commission has eight positions. It

has jurisdiction over compr aints fi red under the city,s ordinance

prohibiting 'discrimination. currentry, two B'r acks and three

l{ex i can-Amer i cans are serv-i-ng on th i s commi ss i on.

. The city Housing Authority has five members.

Currently, one Black and one llexican-American are serving on this

Author i ty. .

29' The Planning commission has nine positions. currently,

one Bl ack and tro Hispanics are serving on this commission. From

I975-80' a llexican-American chaired the planning Commission. The

current Chairperson is a llexican_American.

30- The private Industry councir has trenty members.

Currently, four Bl acks and seyen llexican-Americans are serving.

31. The Austin community college Board consists of nine

nembers. Initially, the Board ras appointed, it is nor elected

at-Iarge (but only three of the nine seats have come up for

election).

three members, all

one Black and one

32- The Austln Cornnunlty Col lege Eoard has f our nlnorlty

nenbers. Tro rre Black and tro are llexlcan-Amerlcan.

33. The Austin Independent School Dlstrlct and Austln

connunity col lege District have the same boundarles. The

minority population of the district ls I8.3I Hispanic and 11.3t

Black.

34. The Austin Human Rel ations Commission ras establ ished

in 1967.

35. The Equal 0pportunity for Enployment 0rdinance, l{o.

75-0710-A, nakes it unl awful to discriminate in employment on the

basis of race, coIor, rel igionl s€x, sexuar orientation, national

original, rg€, or physical handicap. It ras passed in 1975.

36. In 1976 the city passed a publ ic Accommodation

0rdinan-ce' ilo.76 04-01-0. It made illegal disc.rimina!ion against

virtua'l ly any groups, inc'tuding nrinorities, by hotels, motels,

restaurants, theatres, bars, aI I retail establishments, and other

establishments serving the pub'l ic.

37- The Fair Housing 0rdinance, r{o. gz 021g-0, ras

originally passed in 1977, iod amended and strengthened in lgg2.

It prohibits discrimination in housing on the basis of race.

38. The Court finds that 6Ot of the City's t273 niIIion in

community deyelopment block grant funds from 1979-.l9g4 ras

specifical ly housing rel ated. Additional Iy, the Court finds that

the Austin Housing Finance Corporation ras establ ished by the

city to make mortgage loans to Ior-income persons from funds made

available through city-issued bonds.

,E

39. Austln has budgeted tr6 milllon for the Hedlcal

Asslstance Program for the current fiscal year lgg4-95. Thls

progrlm ls 'operated entirely from local non-federal fundlng. It

provides essentia'l nredlcal servlces for the poor.

40. The city shares the cost rith rravis county for the

operati on of a shel ter for trans i ents.

41.