Osborne v. Purdome Petitioners' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Osborne v. Purdome Petitioners' Reply Brief, 1951. d0d1f175-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/569198be-1db4-4f45-bc8d-bd67e4ede007/osborne-v-purdome-petitioners-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

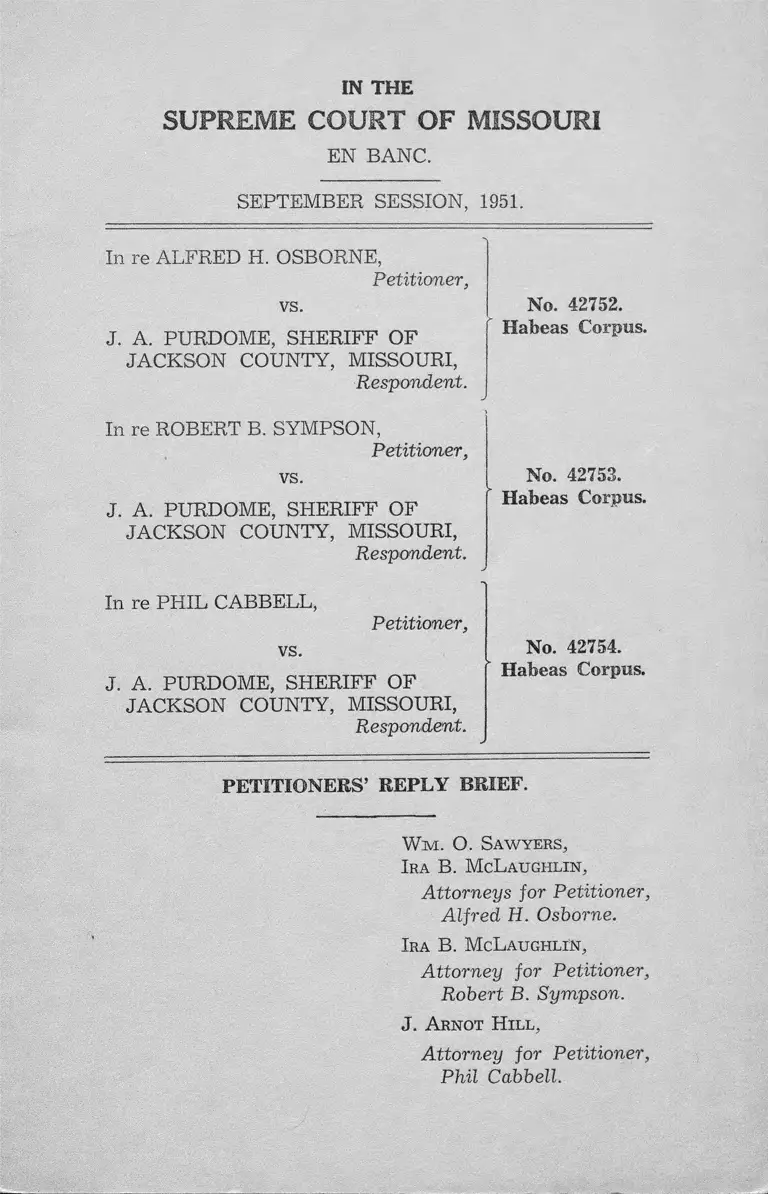

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI

EN BANC.

SEPTEMBER SESSION, 1951.

In re ALFRED H. OSBORNE,

Petitioner,

vs. No. 42752.

J. A. PURDOME, SHERIFF OF Habeas Corpus.

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI,

Respondent.

In re ROBERT B. SYMPSON,

Petitioner,

vs. No. 42753.

J. A. PURDOME, SHERIFF OF ' Habeas Corpus.

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI,

Respondent.

In re PHIL CABBELL,

Petitioner,

vs. No. 42754.

J. A. PURDOME, SHERIFF OF

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI,

Respondent.

' Habeas Corpus.

PETITIONERS’ REPLY BRIEF.

Wm . O. Sawyers,

Ira B. McLaughlin,

Attorneys for Petitioner,

Alfred H. Osborne.

Ira B. McLaughlin,

Attorney for Petitioner,

Robert B. Sympson.

J. A rnot H ill,

Attorney for Petitioner,

Phil Cabbell.

PETITIONERS’ REPLY BRIEF.

Foreword.

Respondent did not, in harmony with Rule 1.08 (c),

endeavor to “ correct any errors” in petitioners’ statement

of facts. Respondent made an independent statement of

facts, which, we believe, erroneously shades the picture.

We will refer to the pages of the record, in the course of

our reply, where we believe the facts of record correct the

more important of these errors. Otherwise, we reply in

the order of the points involved.

I.

The allegations in the answers of petitioners that

Judge Hunt “was, in fact, prejudiced against this peti

tioner and in said cause was not wholly unprejudiced”

are not mere legal conclusions; they are allegations of

ultimate fact and admitted by the demurrers.

Even opposite counsel concede, and the authorities

they cite (Br. 22) sustain, the principle that the demurrers

admit the facts that are well pleaded. Counsel assert,

however, that the above quoted portion of the within an

swers are mere “ argumentative conclusions of law.”

(1) In the case of State vs. Creighton, 52 S. W. (2d)

556, 5.63; 330 Mo. 1176, this court considered the sufficiency

of supporting affidavits made under what is our present

Section 545.660, R. S. Mo., 1949. The challenged portion

thereof read:

“ * * * ‘will not afford defendant * * * a fair and

impartial trial in said cause for the reason alleged in

said petition, to-wit that * * * (the judge) will not

afford the defendant a fair and impartial trial on

account of his bias and prejudice against the de

fendant.’ ”

It was claimed that this allegation was insufficient in

that it stated “ only conclusions and not facts” , but this

court held:

2

“The distinction between ultimate facts and con

clusions is sometimes difficult to draw; * * * we hold

the second application was sufficient; * * *”

Allegations analogous to the one here considered have

many times by this court been ruled sufficient in con

nection with affidavits disqualifying a trial judge.

In the Irvine case, infra, many such cases are cited

and it was held that the sufficiency of the allegation in

question is “ too well settled to justify further discussion.”

State vs. Irvine, 72 S. W. (2d) 96, 99; 335 Mo. 261.

(2) In the case of State ex rel McAllister vs. Slate,

214 S. W. 86; 278 Mo. 570, the files in this court reveal that

the petition for prohibition alleged that “ a petition for

change of venue” was filed in the Circuit Court alleging:

“ * * * that the Honorable John G. Slate, judge of

this court is prejudiced in this cause against the State

and that by reason of such prejudice the said judge,

by the terms of Section 5198, R. S. 1909, is disquali

fied from sitting as judge of this court upon the trial

of this cause * * *”

Attached to said petition is a certified copy of the so-

called petition for change of venue. It charges the judge

of the Circuit Court with prejudice in the same language

as above set forth.

In the said petition for prohibition in the files of this

court there is also the following allegation:

“ * * * The petitioner further states and avers that

the said John G. Slate, judge as aforesaid, in truth

and in fact was and is now prejudiced against the

State in the case of State vs. John W. Scott, No. 1879 * *

The opinion in the Slate case (214 S. W. 1. c. 86) reads:

“ Our preliminary rule was, as above stated, is

sued, and for return thereto respondent admits all 'of

the allegations of said petition except the fact of his

prejudice in any degree in favor of said Scott or

3

against the State of Missouri, which fact of prejudice

he categorically denied. * * * The denial by respondent

of the alleged fact of his prejudice raised an issue of

fact in the case.”

In the Slate case a commissioner was appointed, tes

timony adduced, his report made and sustained, and judg

ment was entered making absolute the preliminary rule

in prohibition.

In the case at bar the allegations of petitioners in

their petitions and affidavits filed in the Circuit Court with

reference to the prejudice of Honorable Thomas R. Hunt

(Tr. 110-112; 114-116; 127-129) are singularly analogous

to those in the Scott case made as to the prejudice of Hon

orable John G. Slate. In the case at bar the allegations

in the answers of petitioners to the returns of respondent

as to the prejudice in fact of Honorable Thomas R. Hunt

are singularly analogous to the allegations of prejudice in

fact of Honorable John G. Slate made in said petition for

prohibition.

In the Slate case the petition for prohibition was filed

by the chief law officer of our state, the attorney general.

In the Slate case the denial “ of the alleged fact of his

prejudice,” made by respondent, “ raised an issue of fact.”

In the case at bar the demurrers of respondent to the an

swers of petitioners admit the ultimate fact of prejudice

in fact alleged as to the Honorable Thomas R. Hunt.

In the Slate case the state relied upon Section 5198, R.

S. 1909. In the case at bar petitioners relied upon the same

statute, now Section 545.660, R. S. Mo., 1949. In the Slate

case the state moved that respondent, circuit judge, pro

ceed in accordance with the provisions of Section 5201,

R. S. 1909 (214 S. W., lc 86). In the case at bar peti

tioners (accused) moved that the Honorable Thomas R.

Hunt, circuit judge, proceed in accordance with the pro

visions of the same statute, now Section 545.690, R. S. Mo.,

1949.

(3) The federal cases cited by respondent as to the

requirements of an affidavit of prejudice of a judge of the

United States District Court are not in point. There is

no analogy whatever between the state and the federal

4

procedure in this respect. Section 144 of 28 USCA ex

pressly requires the “ affidavit shall state the facts and

the reasons for the belief that bias or prejudice exists

* * There is no provision comparable to this in the

Missouri practice.

(4) Opposite counsel take the position that the Mis

souri rule is that the change of venue statutes and change

of judge statutes do not apply to contempt cases; yet, they

do not cite one Missouri case in which that point was

ruled.

The desperate effort of opposite counsel to avoid the

provisions of Section 545.660, R. S. Mo., 1949, which clearly

applies to all criminal prosecutions, is as obvious as it is

futile. They take the groundless position that a prosecu

tion for constructive criminal contempt of court is not

a “prosecution for a criminal offense.” They invoke the

provisions of Section 476.120, R. S. Mo., 1949, prescribing

the penalty of fine and imprisonment, but ignore Section

556.010, R. S. Mo., 1949, defining a criminal offense. Said

section reads:

“ The term ‘crime’, ‘offense’, and ‘criminal of

fense’, when used in this or any other statute, shall

be construed to mean any offense, as well misde

meanor as felony, for which any punishment by im

prisonment or fine, or both, may by law be inflicted.”

(Emphasis ours).

Opposite counsel argue (Br. 16, 20, 24) that “ it was

settled in Missouri that contempt cases are sui generis and

that neither the provisions of the codes of civil procedure

or criminal procedure can be said to be applicable as a

matter of course” unless “ expressly included, eo nomine

in the written law” (Br. 26). They quote the following

dictum (Br. 16) from the opinion in the case of State ex

rel C. B. & Q. R. Co. vs. Bland, 88 S. W. 28, 31; 189 Mo.

197:

“ It is settled law that contempt cases are sui

generis that one court may not try a case of contempt

against another, that contempt proceedings are sum

5

mary; that there is no constitutional right to trial by

jury, and that no change of venue will lie.”

The Bland case is the only Missouri authority cited in

support of the sui generis argument advanced. The Bland

case, however, did not involve the question of whether one

court may try a case of contempt allegedly committed

against another; it did not involve the question of whether

contempt cases are summary, whether, in such cases

there is a constitutional right to a jury trial or whether,

in such cases, changes of venue will lie. The Bland case

involved and decided one question only, i. e., whether, in

the contempt there considered, an appeal would lie. There

the court ruled that the contempt was a civil action and

that the Missouri statutory procedure relative to appeals in

civil cases was applicable. The Missouri statute relative

to appeals in civil cases did not expressly include, eo

nomine, civil contempt proceedings, but the court in the

Bland case, nevertheless, ruled that a final judgment in a

civil contempt proceeding was appealable. If opposite

counsel read the closing paragraph of the Bland case we

can imagine their great consternation.

The case of State ex rel Osborne vs. Southern, 241

S. W. (2d) 94, expressly ruled that Section 510.120, R. S.

Mo., 1949, providing for (legislative) continuances “ in all

civil cases or in criminal cases” , applied to contempt cases.

Opposite counsel concede (Br. 20) that “ it is entirely

conceivable that the Legislature did intend that it (Sec

tion 510.120) apply to contempt cases” , notwithstanding

the fact that said statute did not expressly include eo

nomine contempt proceedings.

In the case of Gompers vs. United States, 233 U. S.

604; 34 S. Ct. 693, 695, the court considered the applica

bility of the statute of limitations, which concluded:

“ * * * unless the indictment is found or the in

formation is instituted within three years.”

Criminal contempt proceedings were not included, eo

nomine, in this written law, but it was held to apply to

a criminal contempt proceeding. The opinion, in part,

states:

6

“ But the provisions of the Constitution are not

mathematical formulas having their essence in their

form; they are organic, living institutions transplanted

from English soil. Their significance is vital, not

formal; it is to be gathered not simply by taking the

words and a dictionary, but by considering their origin

and the line of their growth. Robertson v. Baldwin,

165 U. S. 275, 281, 282; 41 L. ed. 715, 717, 718; 17 Sup.

Ct. Rep. 326. It does not follow that contempts of

the class under consideration are not crimes, or rather,

in the language of the statute, offenses, because trial

by jury as it has been gradually worked out and

fought out has been thought not to extend to them as

a matter of constitutional right. These contempts are

infractions of the law, visited with punishment as

such. If such acts are not criminal, we are in error

as to the most fundamental characteristic of crimes

as that word has been understood in English speech.

So truly are they crimes that it seems to be proved

that in the early law they were punished only by the

usual criminal procedure, (3 Transactions of the Royal

Historical Society, N. S. p. 147 1885) , and that, at least

in England, it seems that they still may be and pref

erably are tried in that way.”

In Ex parte Grossman, 267 U. S. 87; 45 S. Ct. 332, 333,

335, cited by opposite counsel, the issue was whether the

President had power to pardon a criminal contempt. The

Constitution empowered the President to “ grant * * par

dons for offenses against the United States.” Criminal

contempts were not included, eo nomine, in this written

organic law. In ruling that the President had such power

the court, in part, said:

“ The king of England before our Revolution, in

the exercise of his prerogative, had always exercised

the power to pardon contempts of court, just as he

did ordinary crimes and misdemeanors and as he has

done to the present day. In the mind of a common-

law lawyer of the eighteenth century the word

‘pardon’ included within its scope the ending by the

king’s grace of the punishment of such derelictions,

7

whether it was imposed by the court without a jury

or upon indictment, for both forms of trial for con

tempts were had. Thomos of Chartham v. Benet of

Stamford (1313) 24 Selden Society, 185; Fulwood v.

Fid wood . (1585) Toothill, 46; Rex v. Buckenham

(1665) 1 Keble, 751, 787, 852; Anonymous (1674)

Cases in Chancery, 238; King and Codrington v. Rod-

man (1630) Cro. Car. 198; Bartram v. Dannett (1676)

Finch, 253; Phipps v. Earl of Anqelsea (1721) 1 Peere

Williams, 696.

sj: :jc * * *

Nothing in the ordinary meaning of the words ‘of

fenses against the United States’ excludes criminal

contempts.”

Opposite counsel also cite and quote from (Br. 27)

the case of State ex rel Crowe vs. Shepherd, 76 S. W. 78,

89; 177 Mo. 205, on the question of petitioners’ right to an

impartial judge or a change of judges. The Shepherd

case neither considered nor decided such point. The case

involved contempt of the Supreme Court. There is only

one such court in Missouri. Defendant did not ask to

have the case tried by another court, but he did demand

a jury. In support of his demand for a jury, defendant

(in the Shepherd case) “ incidentally” argued that “ it is

not seemingly fair that he should be tried for contempt

by judges of the court that he has scandalized” and it

was in answer to the demand for a jury that the Supreme

Court used the language quoted by respondent on page 27

of his brief. The second quotation from this case per

tained to the point relative to the power of the Legislature

to abridge the contempt power of this court and not to

the question of whether a change of venue or a change

of judges would lie.

(5) The Shipp and Patterson cases, cited by re

spondent, involve contempts of the Supreme Court of the

United States and Supreme Court of Colorado, respectively.

In each of the respective jurisdictions mentioned there

was only one such court. A justice of such appellate

court is occasionally disqualified and does not participate

in the decision, but in the cases mentioned, no attempt

8

was made to disqualify any of the judges of these courts

and no ruling was made on the point here involved. The

point was made as to whether the alleged contempt was

properly tried in the court in which it allegedly occurred,

but with that point we are not here concerned.

The substitution of another judge in the stead of

Judge Hunt would not have constituted a change of venue.

There is no provision in the Missouri law for a change of

venue on behalf of the state in a criminal prosecution and

it is doubtful if a statute providing therefor would be

constitutional. Nevertheless, the state is entitled to an

unprejudiced judge. Formerly it was held that each

division of the Circuit Court of Jackson County was a

separate court. Now, under our constitution and statutory

provisions it is held to be one court, composed of ten

divisions, and said constitution and statutory provisions,

as well as the rules of this court, provide convenient

facilities for the substitution of judicial personnel.

The reference in our original brief to the proposed

Rules of Criminal Procedure relative to criminal con

tempt would appear to have been misunderstood by coun

sel. We do not contend that Judge Buzard erred in as

signing this proceeding to Division No. 4 of said Circuit

Court. He, doubtless, entered the order (Tr. 5-6) re

quested by prosecuting counsel. The entry was furnished

(Tr. 6) and the language used that is pertinent here is

taken verbatum from dictum found in the Shepherd case,

cited by respondent. We suspect that he properly gave

but little, if any, consideration to said order. As judge of

the Assignment Division of said Circuit Court he had the

right to assign said cause to any division thereof that

might suit the convenience of the judges.

Our reference (Br. 27) to Rule XV of the Proposed

Rules of Criminal Procedure is to make the point that re

spondent’s claim that “ one court may not try a case of

contempt against another” is clearly erroneous as re

spondent seeks to apply it here. Judge Buzard and his

fellow committeemen on the Drafting Committee, ap

pointed by this court in connection with said proposed

rules certainly could not have believed in harmony with

the within contention of respondent. This committee

9

certainly would not intentionally recommend that this

court adopt an unconstitutional rule. A constitutional

right certainly is a “ substantive right” . No such rule

may constitutionally change a “ substantive right” and

the right to be tried before a judge who has jurisdiction

to preside over a trial is certainly a “ substantive right” .

The contention that the change of judges prayed by peti

tioners, nisi, was a request to be tried by a judge who had

no jurisdiction to try the cause leads to absurdity.

It is not our contention that due process of law is

contravened where a charge of criminal contempt is tried

in the court in which the alleged contempt was committed.

It is our contention that, to deprive these accused of the

right to a qualified and impartial judge is not only a con

travention of the due process provisions of the respective

constitutions mentioned, but is a violation of the statutory

and common law of Missouri.

Our request was not that the cause be tried in another

court; it was that it be tried by another judge of the same

court, but one who was not disqualified because of prej

udice.

Even the case of State ex rel Short vs. Owens, 256

Pac. 704, 711 (Okla.), cited by opposite counsel, does not

sustain their contention. It does rule that the Oklahoma

statute relative to changes of venue had no application.

There, however, the court contemned was the Supreme

Court. The opinion did refer to a statutory procedure of

that state, relative to disqualifing judges, that might ap

ply, but which was not invoked.

A significant feature of the Owens case is the quota

tion from Corpus Juris (256 Pac. lc 711) to the effect that

where a court is composed of several divisions, one divi

sion may punish a contempt committed against another

division of the same court. On the same point 17 C. J. S.

p. 65, Sec. 51 reads:

“ However, a court may punish contempts com

mitted against a court or judge constituting one of its

parts or agencies, as in case of a court composed of

several co-ordinate branches or divisions * *

(Emphasis ours).

10

To the same effect is 12 Am. Jur., Sec. 48 on the sub

ject of Contempt.

The application of statutes relative to a change of

judges, seems to depend on the wording of the particular

statute considered. Where, as in Missouri, the judge sit

ting in the stead of the regular judge may exercise the

full power and jurisdiction of the court, such statute is

clearly applicable.

We believe that the following authorities are anal

ogous and persuasive:

State ex rel Russell vs. Superior Court,

138 Pac. 291 (Wash.)

State ex rel Seigjried vs. Superior Court,

138 Pac. 293 (Wash.)

State ex rel Cody vs. Superior Court,

192 Pac. 935 (Wash.)

State ex rel Lindsley vs. Superior Court,

199 Pac. 980 (Wash.)

State ex rel Simpson vs. Armijo,

31 Pac. (2d) 703 (N. M.)

In the Armijo case, the court said:

“ The apparent purpose of Section 1 is to provide

a method or procedure to be followed in disqualifying

a trial judge before whom ‘any action or proceeding,

civil or criminal’ is ‘to be tried or heard’ when it is

the belief of a litigant that such judge cannot proceed

with impartiality. * * *

If the enactment of this law is the declaration of

a policy that our courts must be free from suspicion

or unfairness and is grounded upon the truism ‘that

every citizen is entitled to a fair and impartial trial,

and this right is sacred and constitutional, * * * such

right is as sacred to a litigant in a special proceed

ing or one tried for contempt as to a litigant in a tort

or contract action.” (Emphasis ours).

11

II.

The common law contempt power of the Circuit Court.

Respondent, on this point, relies (1) on Federal Court

decisions and (2) on the Curtis article in 41 Harvard Law

Review 51, principally relative to “The History of Con

tempt of Court” by Sir John C. Fox (1927).

(1) Our reference to constitutional courts means

courts created by the constitution. Excepting the Supreme

Court of the United States, there are no federal consti

tutional courts. The judicial power of the United States

is vested in one Supreme Court and “ in such inferior

courts as the Congress may * * * ordain and establish.”

(Art. Ill, Sec. 1, Constitution of the United States). All

inferior federal courts being created by the Congress, their

powers and jurisdiction are fixed and limited by the Con

gress. The Act of March 2, 1831, limiting the contempt

power of inferior federal courts, which was enacted fol

lowing the impeachment trial of Judge James H. Peck,

was held constitutional (Ex parte Robinson, 86 U. S. (19

Wall.) 505; 22 S. Ct. 205; see also Chapt. IX, The History

of Contempt of Court, by Sir John C. Fox).

The circuit courts of Missouri are among the courts of

this state that are created by our constitution (Art. V,

Section 1, Constitution of Missouri). A similar provision,

creating such courts, was in every constitution of this

state.

When the constitution of 1820 was adopted there was,

and since June 4, 1812 there had been, the provision in

our Territorial Laws (1 Mo. Territorial Laws 8) relative to

a trial by jury, which we quoted in our original brief (Br.

29). This provision was more inclusive than the Magna

Charta, in this: Whereas, the Magna Charta provided

“ * * * judgment of his peers or the law of the land * * *”

(c. 29, Magna Charta, Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, Rawle’s

3rd Rev., Vol. II, p. 2062), the Missouri Territorial Laws

provided “ * * * judgment of his peers and the law of the

land * * *” . Manifestly, the respective constitutions of

this state have “ preserved inviolate” the right to a trial by

jury as provided in our Territorial Laws.

12

Our federal constitution has no such yard stick or

comparable provision. The provisions of the Constitution

of the United States relative to jury trials in civil and

criminal cases are interpreted in the light of the meaning

of the terms used therein by the common law lawyers of

the era in which said constitution was adopted, but no

specific right to a jury trial as was enjoyed previous to

the adoption of the constitution is specifically therein pre

served.

Respondent cites U. S, v. Shipp, 203 U. S. 563; 27 S.

Ct. 165 and Clark v. U. S., 289 U. S. 1; 53 S, Ct. 465. These

cases are not controlling and we do not believe they

should be considered persuasive because:

(a) The difference between the federal and state

constitutions above mentioned.

(b) The Constitution of the United States does not

define or limit the judicial power of our state courts and

the Congress cannot regulate or control the modes of pro

cedure in Missouri.

Ex parte Gounis,

263 S. W. 988; 304 Mo. 428

Randolph vs. Fricke,

35 S. W. (2d) 912; 327 Mo. 130; cert, denied,

283 U. S. 833; 51 S. Ct. 365

(c) There is no federal common law; no powers are

vested in such courts by the common law and no pro

cedure therein is governed by the common law.

(d) The conclusion reached by the United States

Supreme Court in the above cases as to the states that

have rejected the rule is not supported by the authorities

there cited. In many of these cases the facts did not

render applicable the rule for which we contend and in

many of the states mentioned the rule has not been re

jected. Illustrating:

In re Singer, 105 N. J. Eq. 220; 147 Atl. 328, was in

equity; the rule did not obtain in Chancery at common

law; New Jersey has not rejected the rule (Appeal of

Verden, 97 A. 783). Indiana has not rejected the rule

13

(Dossett vs. State, 78 N. E. (2d) 435). State vs. District

Court (Mont.) is a case of direct contempt, where the rule

does not apply. State vs. Keller (N. M.) and Boorde vs.

Com. (Va.) are cases in which the rule was not invoked,

rejected or even discussed. State vs. Harpers Ferry Bridge

Co. (W. Va.), like the Singer case, supra,, was in Chan

cery.

(2) The Curtis article in 41 Harvard Law Review 51

is based principally on “ The History of Contempt of

Court” by Sir John C. Fox (1927).

The right to a jury trial, founded in the Magna Charta

and enlarged and preserved “ inviolate” in all the constitu

tions that have been adopted in Missouri, deprives our cir

cuit courts of the power to try an issue of fact in con

structive criminal contempt cases and the issue of contempt

vel non is and must be tried on the uncontrovertible sworn

answer of the accused. This same constitutional limita

tion deprives our circuit courts of the power to direct a

verdict of guilty in criminal prosecutions.

The procedure to which we refer is that of the law

courts of the common law—not the Chancery courts or the

court of the Star Chamber. On the point we make in our

original brief, pp. 30-35, Sir John C. Fox, in his History

of Contempt seems to agree with Blackstone. He says (p.

72):

“ In the common law courts, if the defendant in

his examination denied the contempt, he was ac

quitted, but he was liable to be prosecuted for per

jury. In the Court of Chancery witnesses might be

called to contradict the defendant’s evidence.”

See also page 93.

Amercements, at common law, seem akin to the mod

ern assessments of costs or penalties against the losing

party to a cause; akin to penalties that are assessed for

vexatious appeals and probably, at common law, they in

cluded penalties for direct {in facie) contempt. At page

118 Fox says:

“ In cases to which a capiatur did not apply, the

unsuccessful party was declared to be ‘in the King’s

14

mercy’ or ‘in mercy’, that is, he was liable to amerce

ment; if plaintiff, he was amerced for false claim; if

defendant, he was amerced for his wilful delay of jus

tice in not immediately obeying the King’s writ by

rendering the plaintiff his due. In either case con

tempt had been committed. The payment of an amer

cement was enforceable by distress but not by im

prisonment. The amounts fixed upon afferrment were

usually small, and amercement of parties to actions

had become a matter of mere form in the superior

Courts by the year 1478, when this was so declared,

in effect, by all the Justices of the King’s Bench.”

Amercements, it seems, were assessed against sheriffs

for attaching “ these people without warrant” (Fox 135);

against a sheriff for making “ a false return” (Fox 136);

they were assessed for “ withdrawing from the Justices

without license” (Fox 124); for “ default in an appeal”

(Fox 124); “ 1 mark of another for a false oath” (Fox

124); “ for suing in a wrong name” (Fox 134); for “ dis

obedience to a rule of court” (Fox 163) and against an

attorney for apparently erring in procedure, i. e., for suing

“a writ” without a “ bill” (Fox 161). Amercements were

even paid to obtain “ speedy justice” (Fox 145).

We have carefully read “The History of Contempt of

Court” by Sir John C. Fox and we do not believe that it

sustains the contention of opposite counsel. Primarily

the book seems to be an effort to establish that a libel of

court at common law was triable to a jury.

There were 32 confirmations of the Magna Charta be

tween 1215 and 1416 (Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, Rawle’s

3rd Rev., Vol. II, p. 2061) and, doubtless, its mandates

were often contravened. The history by Fox, however,

we respectfully submit does not justify the statement in

Respondent’s Brief, pp. 33-34 that Fox “ never had any

doubt that the Magna Charta did not extend the right of

trial by jury to officers of the court who committed con

tempts * * * out of the presence of the court * *

The History of Contempt of Court by Sir John C.

Fox pp. 227-242 correlates 82 “ Instances * * of contempt

committed * * * tried by a jury, or by confession.”

15

Instance No. 13, on page 229 is as follows:

“ (13) A. D. 1293

(21 Edward I.) Rot. Pari., i, 94b.

Placita coram ipso domino rege et consilio suo ad

Parliamentum suum. The complainant alleges that the

Sheriff of Devon has not executed a writ, in contempt,

etc. The Sheriff pleads that he never received the

writ and puts himself upon the country, and the plain

tiff does the like. To be tried by a jury of twenty-

four.

Note. If an officer of justice could claim a trial

by jury, a fortiori, a stranger.”

Instance No. 75 on page 241 is as follows:

“ (75) A. D. 1607

(5 James I.) Fuller’s Case, 12 Reports, 41.

Resolved by all the Judges that if a Counsellor

at law in his argument shall scandal the King or his

government, this is a misdemeanor and contempt to

the Court; for this he is to be indicted, fined, and im

prisoned.” (Emphasis ours)

Fuller’s case can be found in the library of this court

(77 Eng. Rep. 1322). The date thereof is the year of the

founding of King James’ Colony.

We are doubtful of the effect, if any, of the Missouri

statute adopting the common law, on the contempt powers

of our circuit courts. (Petitioners’ Brief p. 35). We are

confident, however, that the provisions of our constitu

tion, preserving “ inviolate” the right of trial by jury, as

theretofore enjoyed, render our circuit courts without

power to try issues of fact without a jury in criminal prose

cutions. We are also confident that both history and

authority sustains the proposition that the law courts of

the common law tried constructive criminal contempts

to a jury until the practice was ordained to try such con

tempts on the uncontrovertible sworn answer of the ac

cused, where such answer was made.

16

In Dickey vs. Volker, 11 S. W. (2d) 278, 285; 321 Mo.

235, this court said:

“ * * * the courts of this country, in order to as

certain the principles and rules of the common law,

may look to the decisions of other states of the Union

* *

The case of Hawkinson vs. Johnson, (Mo.), 122 Fed.

(2d) 724, announces a similar doctrine.

This we have sought to do and we respectfully submit

that the authorities cited in our original brief, pp. 28-37

sustain the contention we there make. Somehow we are

not convinced that either Curtis or Sir John C. Fox are

more authentic or more reliable than 3 Translations of the

Royal Historical Society, cited by the Supreme Court of

the United States in Gompers vs. U. S., supra. If we had

the facilities and the time to make an exhaustive historical

research, we doubt if we have the ability to improve on

the written opinions of the learned judges that are to be

found in the many cases we have cited in support of this

point.

III.

Perjury alone does not constitute contempt of court.

We make this point here because the attempt was to

charge perjury, to prove perjury and to find perjury.

While these attempts were not successful, even if they

had been, contempt of court would not have been estab

lished.

All of the accused named in paragraph 5 of the com

plaint (Tr. 3) are alleged suborners of the perjury which,

by inference, is charged to have been committed by the

“ two alleged witnesses” mentioned. True, it is not charged

that Jones and Everage, who are mentioned in paragraph

6 of the complaint, are the “ two alleged witnesses” men

tioned in paragraph 5 of the complaint. However, it is

not pretended that the attempt was other than to charge

petitioners with subornation of perjury. Opposite coun

sel concede (Br. 45, 50) that

17

“ the basis of the charge against petitioners is

that they confederated to act and did individually act

to locate, arrange for, coach and present to the trial

court and jury two witnesses who testified to ‘the oc

currences out of which the law suit of Burton vs.

Moulder arose’ , when in fact neither witness saw

these occurrences and petitioners knew they did not.

Petitioners are not charged with perjury or false

swearing. None of them testified as witnesses.”

Perjury, as defined by statute (Sec. 557.010, R. S.

Mo., 1949), has all the elements of perjury at common

law. An accessory before the fact of perjury is one who

“ procures, counsels or commands another to commit the

crime.”

Blackstone’s Commentaries (Chitty’s Blackstone),

Book 4, Chapt. Ill, Star pp. 34, 36

Wharton’s Criminal Law (11th Ed.),

Vol. I, p. 335, Sec. 263

Bishop on Criminal Law (9th Ed.),

Vol. I, p. 486, Sec. 673

Such accessory before the fact is a statutory prin

cipal (Sec. 556.170, R. S. Mo., 1949). One who procures

another to commit perjury is guilty of subornation of

perjury (Sec. 557.040, R. S. Mo., 1949).

Thus, under our statute and at common law a sub

orner of perjury is nothing more or less than an accessory

before the fact of perjury. Subornation of perjury is an

accessorial crime.

70 C. J. S., pp. 548, 549, Sec. 79 (b)

Hammer vs. United States,

271 U. S. 620; 46 S. Ct. 603

Opposite counsel have evolved a novel and amazing

theory, i. e., that a perjurer is not guilty of contempt, but

one who procures the commission of perjury is guilty.

They say (Br. 55):

“While it is probably true that sheer false testi

mony by a witness is not criminal contempt (In re

Michael, 326 U. S. 224, 66 S. Ct. 78; Ex parte Creasy,

18

(Mo.) 148 S. W. 914), it is likewise true that con

duct which also may constitute the crime of suborna

tion of perjury can be and is criminal contempt.”

A succinct statement of what opposite counsel claim

constituted the obstruction (Br. 50) follows:

“ If the acts of locating, arranging for, coaching

and presenting false testimony tend to degrade or

make impotent the authority of the trial court or ob

struct or impede the administration of justice, the

complaint charges criminal contempt.”

Thus, it is conceded that the obstructive tendency of

perjury “ to produce a judgment not resting on truth” is

the sole and only obstruction that is the “ basis or founda

tion” of the within charge. This does not constitute

contempt. Such use of the contempt power, to paraphrase

the opinion in the Michael case, is to “ permit too great in

roads on the procedural safeguards of the Bill of Rights.”

We consider the case of Ex parte Creasy, 243 Mo. 679;

148 S. W. 914, 921, 924 controling and the case of In re

Michael, 326 U. S. 224; 66 S, Ct. 78, 80 highly persuasive.

The element of obstruction in the federal statute (28

USCA 401) is in harmony with the Missouri statute (Sec.

476.110, R. S. Mo., 1949) and the common law.

In the Michael case, supra, (66 S. Ct. lc 80) the Su

preme Court said:

“All perjured relevant testimony is at war with

justice, since it may produce a judgment not resting

on truth. Therefore it cannot be denied that it tends

to defeat the sole ultimate objective of a trial. It need

not necessarily, however, obstruct or halt the judicial

process. For the function of trial is to sift the truth

from a mass of contradictory evidence, and to do so

the fact finding tribunal must hear both truthful and

false witnesses. It is in this sense, doubtless, that this

Court spoke when it decided that perjury alone does

not constitute an ‘obstruction’ which justifies exertion

of the contempt power and that there ‘must be added

to the essential elements of perjury under the general

19

law the further element of obstruction to the Court in

the performance of its duty.’ Ex parte Hudgings,

supra, 249 U. S. 382, 383, 384, 39 S. Ct. 339, 340, 63 L.

Ed. 656, 11 A. L. R. 333. And the Court added ‘the

presence of that element (obstruction) must clearly

be shown in every case where the power to punish for

contempt is exerted.’

* * * ^ * * *

Only after determining from their testimony that

petitioner had wilfully sworn falsely, did the Court

conclude that petitioner ‘was blocking the inquiry just

as effectively by giving a false answer as refusing to

give any at all.’ This was the equivalent of saying

that for perjury alone a witness may be punished for

contempt. See. 268 is not an attempt to grant such

power” (Emphasis ours).

In U. S. vs. Goldstein, (1947) 158 Fed. (2d) 916, 920 (7

Cir.) the court said:

“ The question as to whether the allegations of the

petition are sufficient to show an obstruction of justice

divides itself into two categories, legal and factual. As

to the legal phase of the situation, the law appears to

have been definitely established by four recent de

cisions of the Supreme Court. In re Michael, 326 U. S.

224, 66 S. Ct. 78; Nye v. United States, 313 U. S. 33, 61

S. Ct. 810, 85 L. Ed. 1172; Clark v. United States, 289

U. S. 1, 53 S. Ct. 465, 77 L. Ed. 993, and Ex Parte

Hudgings, 249 U. S. 378, 39 S. Ct. 337, 63 L. Ed. 656,

11 A. L. R. 333. We have read and reread these cases,

and notwithstanding counsel’s valiant effort to dis

tinguish them, we are of the view that they point un

erringly to the conclusion as a matter of law that

Goldstein’s perjury did not amount to an obstruction

to the administration of justice in this court. * * *

In the instant situation, there appears to be no

escape from the idea that any interference with the

judicial power of this court was only that ‘inherent in

the wrong of testifying falsely.’ In other words, the

perjury alleged is not merely one of the aggravations

20

of the contempt charged hut is the basis or foundation

therefor” (Emphasis ours).

In the case of U. S. vs. Arbuckle, 48 F. Supp. 537, 538,

the court quotes Ex Parte Hudgings, supra, and said:

“ What, then, is perjury having the ‘obstructive

effect’ to which the Supreme Court referred? A study

of the decided cases which bear on this point seems to

establish that it is ‘perjury which blocks the inquiry.’

This is the definition given by Hand, J., in United

States v. Appel, D. C., 211 F. 495, a case referred to

by the Supreme Court, in its Hudgings’ decision, as

illustrating its view. If false testimony given in a

case results in defiance of the Court or in frustration

of its right to obtain testimony, then the witness in

legal effect is contumacious, he is a contemnor, as well

as a perjurer, and may be punished for contempt. But

if the witness fully gives testimony, and in so doing

testifies falsely, not in order to prevent the inquiry,

but only in order to deceive, there is no contumacity,

no blocking of the inquiry, and the remedy is solely

by indictment for perjury and trial by jury.”

We are at a loss to understand the position of re

spondent on this point. On the one hand we are told

that “ * * * it is probably true that sheer false testimony

by a witness is not criminal contempt” and the Creasey

and Michael cases are cited (Br. 55). On the other hand

opposite counsel assert “ Other cases have also uniformly

labeled as contemptuous the act of procuring and present

ing false testimony because necessarily the solicitation

and presentation of perjured testimony robs the parties

of a fair trial” (Br. 53). Such diametrically opposite con

tentions simply neutralize each other.

Again, they say “ false testimony” is the obstruction

or impediment to the administration of justice upon which

the charge is based (Br. 50). On the other hand the

arranging for false testimony is asserted to be contemp

tuous, even had the testimony so arranged for, never been

given (Br. 56). Never has a preparation for the commis

21

sion of a crime rendered one guilty of the crime. Never

has an accessary before the fact been convicted unless it

was found that the crime had been committed by the

principal.

Perjury which “ blocks the inquiry” , which prevents

a court from obtaining testimony, can constitute contempt,

but such is not this case. With reference thereto, in 12

Am. Jur., Sec. 17, on the subject of Contempt, it is stated

“ * * * In order that perjury may constitute con

tempt of court, however, it must appear that (1) the

alleged false answers had an obstructive effect; (2)

that there existed judicial knowledge of the falsity of

the testimony; and (3) the question was pertinent to

the issue.”

See also:

Favick Airflex Co. vs. United Elec. R. & M. Wkrs.,

92 N. E. (2d) 436 (Ohio)

People vs. Bullock,

82 N. E. (2d) 817 (111.)

People vs. Hille,

192 111. App. 139

Riley vs. Wallace,

222 S. W. 1085 (Ky.)

People vs. Anderson,

272 111. App. 93

Mclnnis vs. State,

32 So. (2d) 444 (Miss.)

Wilder vs. Sampson,

129 S. W. (2d) 1022 (Ky.)

IV.

The insufficient complaint, judgment and commit

ment.

As pointed out by petitioners (Br. 39), the “ particu

lar circumstances” of the offense must be set forth in the

commitment (judgment) and, since the judgment must

be within the scope of the charging paper, the “ par

22

ticular circumstances” of the offense must be set forth

in the complaint, else the judgment is not supported by

the charge and the court is without jurisdiction.

Respondent argues that the recitation of the testimony

given by Everage is a part of the judgment. Petitioners

assert that such recitation is no more a part of the judg

ment than the other preliminary recitations which give a

history of the proceedings—see definition of judgment

(Sec. 511.020, R. S. Mo., 1940).

However, even if the recitals in the order as to the

testimony of Everage are so erroneously considered, the

judgment will not be supported by the allegations of the

complaint, since no comparable allegations are there to

be found, and few, if any, of the many insufficiencies

pointed out by petitioners, both in the complaint and in

the judgment (Br. 39, 40, 41, 42, 51, 52, 53) will be sup

plied (by unwarranted inference or otherwise).

A comparison of Paragraph III (d) of Respondent’s

Brief, p. 49, with Paragraph 5 of the complaint (Tr. 3) re

veals:

It is not charged that the named accused “ presented

the testimony of Jones and Everage as to the ‘occurrences

out of which the law suit * * * arose.’ ” The charge is

that said named accused and Jones and Everage presented

two unnamed witnesses, who never actually witnessed

the “ occurrences * * * etc.”

Paragraph 6 of the complaint (Tr. 3) alleges that the

named accused arranged to have Jones and Everage falsely

and fraudulently testify and Paragraph 7 of the complaint

(Tr. 3) alleges that they did so testify, but it is not charged

that the two unnamed witnesses mentioned in said Para

graph 5 were Jones and Everage.

Respondent says (Br. 58) that petitioners were charged

with presenting false testimony on liability. The com

plaint does not mention liability and the judgment makes

no mention of liability. In fact, at no place, either in the

complaint, the recitation of the testimony of Everage or

the findings of the court in the judgment and commit

ment, is there any fact mentioned relative to the nature

of the case of Burton v. Moulder, the issues therein, the

23

facts to which Jones and Ever age testified at the trial

thereof, or the materiality, if any of their testimony.

We have here illustrated a few of the many inac

curacies in respondent’s statement of the facts. At the

above mentioned pages of our brief, petitioners specif

ically referred to the many insufficiencies in both the

complaint and the judgment. These will not here be re

argued [Rule 1.08 (d) ], but we confidently assert that the

record will sustain our contention.

The California law is similar to the Missouri law we

mentioned on page 39 of our original brief with refer

ence to the necessity of alleging the “ particular circum

stances” of the offense in the charging paper and of set

ting them forth in the judgment or commitment.

In the case of Ex parte Battelle, 277 Pac. 725 (Cal.),

the court said:

“ Bearing in mind this fundamental principle of

procedure in contempt cases of this character, when

we refer to the order and adjudication of contempt

which the senate purported to adopt and enforce in

the instant case, we find it to be entirely lacking in

that precision of statement which the law requires.

It is true that the order in question contains the

recital that ‘in pursuance of said subpoena duly and

regularly issued and served said persons appeared be

fore said committee and refused and declined to an

swer certain questions material to the issues, and re

fused to produce proper books, papers, documents and

records required of them, such being in their posses

sion or under their control, and material to said is

sue, all as more particularly appears from the report

of said committee presented to and filed with this

Senate on March 8th, 1929, and from the supplemental

report of said committee filed with this Senate on

March 11th, 1929, said questions being also set forth

in the ‘Excerpts from the transcript of testimony’ sub

mitted to the Senate March 8th, 1929, to which refer

ence is hereby made.’ We are of the opinion, how

ever, that the mere ‘reference’ which is thus made to

24

the report of the committee and to said ‘questions be

ing also set forth in the ‘Excerpts from the transcript

of testimony’ are and each of them is insufficient to

so far embody the content of such report or the ‘Ex

cerpt from the transcript of testimony’ therein con

tained in the order of commitment so as to satisfy the

precise requirement of the Code of Civil Procedure

with respect to what the ‘recitals’ in said order must

contain.”

See also Ex parte Wells, 173 Pac. (2d) 811 (Cal.).

In Ex parte McLain, 221 Pac. (2d) 323 (Cal.), the

court said:

“ In cases of constructive contempt, as is this, not

only the order hut also the affidavit upon which it

is based must sufficiently charge the alleged facts con

stituting the offense. In re Davis, 31 Cal. (2d) 451;

189 P. (2d) 283.

Applying this test to the order, and the affidavit,

it becomes immediately apparent that each order is

lacking in the essential allegations of materiality and

pertinency of the records, and that the Superior Court

was without jurisdiction to hear the case, or to adjudge

contempt. The affidavit states conclusions; and the

only statement of materiality in the order is by refer

ence to the affidavit. * * *

This case turns upon elementary principles of due

process of law. Before any man may be imprisoned he

is to know in the affidavit charging him with construc

tive contempt in what respect records which he is

ordered to produce are material to the investigation.

* * *” (Emphasis ours).

In the case of Leonis vs. Superior Court, 223 Pac. (2d)

657 (Cal.), the court said:

“Unless the affidavit initiating the proceeding

‘contain a statement of facts which show on its face

that a contempt has been committed, the court is

without jurisdiction to proceed in the matter and any

judgment of contempt thereon is void. Nothing can

25

be proved that is not charged, and if the affidavit is

materially defective, the judgment found upon it must

necessarily be equally defective.’

# * * S}5 *

* * * Undoubtedly the power to punish for con

tempt is a necessary adjunct to procedure. Its appli

cation, however, must be hedged about with adequate

protection for the person accused; otherwise, the basic

constitutional requirements concerning due process

and other fundamental rights are without meaning.”

(Emphasis ours).

V.

Insufficient evidence.

The response of Everage (Tr. 56, 57) was not a plea

of guilty. No disposition of the cause as to Everage and

no finding of his guilt was made until the close of the trial

(Tr. 77). Even the evidence of Helen Everage, wife of

Vernon Everage, was received in evidence and limited in

its application to establishing the guilt of her husband,

Vernon Everage (Tr. 387). This was done on the theory,

as stated by the court, that, if counsel for informant

“ wants to offer further evidence against him (Everage),

I will hold it against him. He could be on the theory that

the court might not believe Everage’s story direct” (Tr.

388).

Everage was jointly charged with these petitioners

when he testified; the cause had not been disposed of as

to him when he testified. Everage was, therefore, an in

competent witness against these petitioners, under the au

thorities cited (Br. 55, 56).

As to Cabbell: The facts recited in Respondent’s

Brief (Br. 76-77) are not supported by the record:

(1) What Sympson told Everage relative to Cabbell

(Tr. 247) is not only unintelligible, but is not binding on

Cabbell.

(2) The conclusion that “ * * * Cabbell’s car was to

have been the Ford, etc.” (Tr. 246), was objected to and*

on motion, stricken (Tr. 246-257).

26

Therefore, the evidence as to Cabbell was that he was

merely present and the proof was wholly insufficient, as

pointed out by petitioners (Br. 56-57).

Respectfully submitted,

W:m . O. Sawyers,

Ira B. McLaughlin,

Attorneys for Petitioner,

Alfred H. Osborne.

Ira B. McLaughlin,

Attorney for Petitioner,

Robert B. Sympson.

J. A rnot H ill,

Attorney for Petitioner,

Phil Cabbell.