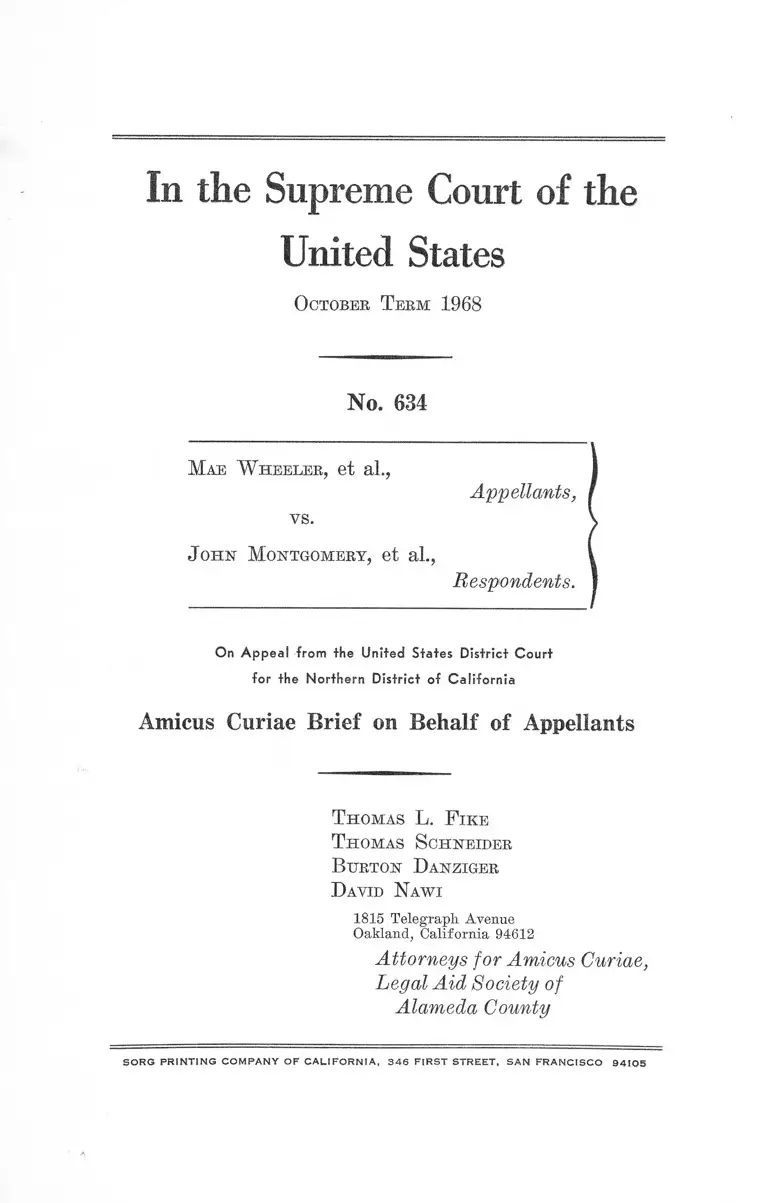

Wheeler v. Montgomery Brief Amicus Curiae on Behalf of Appellants

Public Court Documents

June 20, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wheeler v. Montgomery Brief Amicus Curiae on Behalf of Appellants, 1969. 406093ec-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/57fa6782-f931-4694-8b5f-2a048a97d40e/wheeler-v-montgomery-brief-amicus-curiae-on-behalf-of-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

In the Supreme Court o f the

United States

October T eem 1968

No. 634

Mae W heeler, et ah,

vs.

J ohn Montgomery, et al.,

Appellants,

Respondents.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

Amicus Curiae Brief on Behalf o f Appellants

T homas L. F ike

T homas Schneider

B urton Danziger

David Nawi

1815 Telegraph Avenue

Oakland, California 94612

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae,

Legal Aid Society of

Alameda County

S O R G P R IN T IN G C O M P A N Y O F C A L IF O R N IA , 3 4 6 F IR S T S T R E E T , S A N F R A N C IS C O 9 4 1 0 5

SUBJECT INDEX

Interest of Amicus Curiae, Legal Aid Society of Alameda

County ........................................................................ 1

Summary of Argument ........................................ 3

Argument.......................................................................................... 6

I. The notice and informal conference provided by the

challenged regulation prior to termination of benefits by

a county welfare department do not afford the protec

tions required by due process........................................... 6

A. There is no compelling public necessity or other

justification for the procedural inadequacies of the

regulation............................................. 8

B. A decision to terminate categorical aid benefits is

an adjudicatory act, requiring, as a minimum, ade

quate notice, opportunity for confrontation and

cross-examination, a decision based on evidence

produced at a hearing, an impartial trier of fact,

and a decision on the merits. The challenged regu

lation provides none of these................................... 10

1. The regulation fails to provide adequate notice 10

2. The regulation provides no opportunity to test

the credibility and probative value of evidence 12

3. The regulation fails to reqire a decision based

on evidence produced at a hearing.................... 13

4. The regulation fails to provide an impartial

trier of fa c t .......................................................... 14

5. The regulation fails to require a decision on

the merits.............................................................. 16

C. The availability of a subsequent hearing does not

justify the elimination of an adequate prior

hearing ........................................................................ 17

II. The notice and informal conference provided by the

challenged regulation prior to termination of categori

cal aid benefits by a county welfare department do not

afford the protection required by the California Legis

lature .................................................................................... 22

Page

11 S u bje c t I n d e x

Conclusion ........................................................................................ 28

Appendix A— California State Department of Social Welfare

Public Social Services Manual Regulation 44-325 ...........App. 1

Appendix B—A Comparison of Certain Procedures of Selected

Administrative Agencies...................................................... App. 11

Page

Appendix C— “ Opposition to Introduction of Additional Evi

dence ’ ’ filed by California Attorney General in the Court of

Appeal of the State of California in McCullough vs.

Tei'zian....................................................................................App. 17

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases Pages

Armstrong v. Manzo (1965) 380 U.S. 545 ................................... 9

Cafeteria & Restaurant Workers Union v. McElroy (1961)

367 U.S. 886 ....................................................... -................... 4, 8, 21

Carroll v. California Horse Racing Board (1940) 16 C.2d 164,

105 P.2d 110 .............................................................................. 23

Covert v. State Board of Equalization (1946) 29 C.2d 125, 173

P.2d 545 .............................................. .......................................23, 25

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education (5 Cir. 1961) 294

F.2d 150, Cert. Den 368 U.S. 930 ...........................8,14,19, 20, 21

Edwards v. California (1941) 314 U.S. 160............................ 9

Endler v. Schutzbank (1968) 68 C.2d 162, 436 P.2d 297, 65

Cal Rptr 297 .................................... -........................................ 7, 8

English v. City of Long Beach (1950) 35 C.2d 155, 217 P.2d

22, 18 ALR 2d 547 .................................................................. 7,13

Escobedo v. State of California (1950) 35 C.2d 870, 222 P.2d 1 27

Fascination Inc. v. Hoover (1952) 39 C.2d 260, 246 P.2d 656 21

Goldberg v. Regents of University of California (1967) 248

C.A.2d 867, 57 Cal Rptr 463 .................................................. 21

Gonzalez v. Freeman (D.C. Cir. 1964) 334 F.2d 570 .............. 21

Greene v. McElroy (1959) 360 U.S. 474 ...........................7,12,13, 23

Hannah v. Larche (1960) 363 U.S. 420 .............-........................ 7

Hornsby v. Allen (1964) 326 F.2d 605 .................................. 7,10, 21

I.C.C. v. Louisville & N.R. Co. (1912) 227 U.S. 8 8 ...........14,17, 21

In re Murchison (1955) 349 U.S. 133 ...................................... 7

Keenan v. S.F. Unified School District (1950) 34 C.2d 708,

214 P.2d 382 .............................................................................. 26

Kelly v. Wyman (S.D.N.Y. 1968) 294 F.Supp. 893, probable

jurisdiction noted sub nom Goldberg v. Kelly (1969) 37

LW 3399 ................. .'................................ .......................6, 11, 14,15

La Prade v. Department of Water and Power (1945) 27 C.2d

47, 162 P.2d 13 ....................................................................23, 25, 26

Mendoza v. Small Claims Ct. (1958) 49 C.2d 668, 321 P.2d

9 ..............................................................................................17,18,19

iv T able of A u th orities C ited

Pages

North American Cold Storage Company v. City of Chicago

(1908) 211 U.S. 306 .................................................................. 16

Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. P.U.C. (1936) 301 U.S. 292 .......7, 8,13

Parrish v. Civil Service Commission (1966) 66 C.2d 260, 425

P.2d 223, 57 Cal Rptr 623 ...................................................... 20

Ratliff v. Lampton (1948) 32 C.2d 226, 195 P.2d 792, 10 ARL

2d 826 ........................................................................ 23, 24, 25, 26, 27

Russell-Newman Manufacturing Co. v. N.L.R.B. (5 Cir. 1966)

370 F.2d 980 .................................................... .................. ...... 7,10

Shaughnessy v. United States (1953) 345 U.S. 206 ............... 22

Shively v. Stewart (1966) 65 C.2d 475, 421 P.2d 65, 55 Cal

Rptr 217 .................................................................................... 21

Slochower v. Board of Education (1956) 350 U.S. 551 ........... 21

Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp. (1969) .......U.S........... , 37

LW 4520 .......... ........................................................................... 17

Sokol v. Public Utilities Commission (1966) 65 C.2d 247, 418

P.2d 265, 53 Cal Rptr 673 ...................................4, 8, 16, 17, 18, 19

Steen v. Board of Civil Service Commissioners (1945) 26 C.2d

716, 160 P.2d 816 ............. ......... ...................................23, 25, 26, 27

Walker v. City of San Gabriel (1942) 20 C.2d 879, 129 P.2d,

349, 142 ALR 1383 .................................................................. 12, 25

Wasson v. Trowbridge (2 Cir. 1967) 382 F.2d 807 ................... 7,14

Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitness (1963) 373

U.S. 96 ..................................... ................. .......................... ...... 7,12

Constitution

United States Constitution, 14th Amendment........................... 3

Statutes

Calif. Code Civil Procedure

§ H 7 ( j ) ...................................................................................... 18,19

§ 1159 et seq................................................................................ 19

T able of A u th orities C ited v

Calif. Welfare & Institutions Code

§ 10000 ...................................... ................................................. 22

§ 10600 ....................................................................................... 22

§ 10950-10965 ............................................................................ 4

§ 10950 et seq..........................................................................7, 24, 27

§ 11458 .............. 24

§ 12200 .......................................................... ......................... . 23

§ 12700 ........................................................................................ 23

§ 13750 ........................................................................................ 23

R egulations

Supreme Court Rules, Rule 42 .................................................. 3

U.S. Dept, of Health, Education and Welfare, Handbook of

Public Assistance Administration (Federal Handbook)

§ 6200(k) .................................................................................... 9

§ 6200(j) .................................................................................... 27

§ 6300(g) .................................................................................... 9

§ 6500(b) ............... 9

California State Department of Social Welfare

Operations Manual

§§ 22-043—22-065 .................................................................. 27

Public Social Services Manual

§ 44-325.1 ............................ 16

§ 44-325.421 .............. 16

§ 44-325.43 .......................................... 2, 3, 6,10,14, 17,19, 24, 26

Pages

In the Supreme Court o f the

United States

October Term 1968

No. 634

Mae W heeler, et aL,

vs.

J ohn Montgomery, et al.,

Appellants,

Respondents.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

Amicus Curiae Brief on Behalf of Appellants

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE, LEGAL AID SOCIETY

OF ALAMEDA COUNTY

The Legal Aid Society of Alameda County is a non profit

California corporation established in 1929 for the purpose

of furnishing legal services to those residents of Alameda

County who are unable to afford the services of private

attorneys. Staff attorneys of the Society have training and

experience in Welfare law. They are currently representing

plaintiffs and respondents in McCullough v. Tersian,1 a

1. The record on appeal in McCullough v. Terzian, consisting

of a “ Clerk’s Transcript on Appeal” , has been lodged with the

Clerk of this court.. References to “ C.T.” in this brief are references

to said “ Clerk’s Transcript” . Since this is an amicus curiae brief,

the facts of the McCullough case are not before this Court, and it

was thought unnecessary to file a formal record of the California

State Court proceedings.

case now pending in the Court of Appeal of the State of

California, First Appellate District, Division Three, 1 Civil

No. 25830. At issue in that case is the validity with respect

to California statutes and the California and United States

Constitutions of the identical regulation passed on by the

three judge court below and at issue herein, State Depart

ment of Social Welfare Public Social Service Manual 44-

325.43 (hereinafter referred to as PSS 44-325.43).

McCullough is a class action in which plaintiffs and re

spondents represent all persons receiving public assistance

under the categorical aid programs in the State of Cali

fornia. Defendants and appellants are H rayr T erzian, Di

rector of the Alameda County Welfare Department, and

J ohn Montgomery, Director of the Department of Social

Welfare of the State of California. Respondent Montgom

ery was a defendant in the three-judge court below and is

a respondent in the instant appeal.

The trial court in McCullough rendered judgment in

favor of plaintiffs, which judgment declared PSS 44-325.43

invalid “because and to the extent it does not provide a

hearing with adequate procedural safeguards . . . prior to

the withdrawal or termination of public assistance benefits

under the [categorical aid] programs as required by State

law and the United States and California Constitutions.”

(C.T. 103:29-104:6)# The judgment further ordered de

fendant Montgomery to provide categorical aid benefits to

which recipients are otherwise entitled “until a decision, if

any, of ineligibility is rendered” pursuant to the State “ fair

hearing” or its equivalent.

Plaintiffs in McCullough have a direct interest in the out

come of this litigation. Their claim, (and the decision of

the State Trial Court) is based in part on the contention

2

See footnote 1, p. 1, supra.

that PSS 44-325.43 violates due process requirements of

the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitu

tion, which is the very issue presented in the instant case.

This Court’s decision on the scope of Fourteenth Amend

ment due process will provide a minimum standard below

which no state’s law, whether decisional or statutory, may

fall. Furthermore, amicus has carefully studied the Cali

fornia law as it bears on the sufficiency of the procedures

at issue in the instant case, and has concluded that the

State law, as well as federal, compels a reversal of the

judgment of the District Court.

With the consent of both parties pursuant to Rule 42 of

the Supreme Court Rules, Legal Aid Society of Alameda

County respectfully submits its Amicus Curiae brief in

support of appellants.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The District Court has upheld a regulation (PSS 44-325.

43, reproduced in Appendix A) which prescribes the pro

cedure followed in California before welfare benefits are

withdrawn or withheld. The regulation applies only to re

cipients of the “ categorical aids,” Aid to Families with

Dependent Children (AFDC), Aid to the Blind (AB), Aid

to the Disabled (ATD), and Old Age Assistance (OAS).

The regulation requires notice to the recipient, in writing,

immediately after a decison is made to withhold aid and in

no case later than three days before aid is actually with

held. It further provides that the affected recipient will

be given an opportunity within the three days to meet with

a caseworker or other unspecified person to learn the nature

and extent of the information upon which the withholding

action is based, to provide an explanation, and to “ discuss

the matter informally for purposes of clarification and,

where possible, resolution.”

3

It does not provide adequate time to marshall or present

contradicting evidence; it does not provide for the sub

poena and cross-examination of witnesses; it does not pro

vide for a review of the evidence by a clearly designated

and impartial trier of fact; and it does not provide for a

decision on the merits based solely on the record. In short

it contains none of the procedural safeguards expressly

included in the subsequent “ fair hearing” (Calif. Welfare

and Institutions Code §§ 10950-10965 hereafter, W & I

Code) proceedings and generally contemplated by the re

quirement of a hearing.

It is uncontroverted that the constitutional adequacy of

a “ hearing” depends on the nature of the governmental

function as well as the nature of the private interest in

volved. Cafeteria and Restaurant Wothers Union v. Mc-

Elroy (1961) 367 U.S. 886; Sokol v. Public Utilities Com

mission (1966) 65 C.2d 247, 418 P.2d 265.

The District Court opinion is based on the assumption

that the obvious procedural inadequacies of the regulation

(and the error and hardship which necessarily flow there

from) are justified by the availability of a subsequent hear

ing at the state level after termination of benefits by the

County (the fair hearing) and the competing public interest

of time and expediency.

Amicus contends that notwithstanding the availability

of a subsequent hearing due process requires an adequate

hearing prior to the time official action takes effect. An ade

quate hearing is one that preserves all the elements of an

adjudicatory proceeding unless there is a compelling public

interest that requires the omission of one or more elements

of such a hearing. Further, common sense dictates that where

one element of judicial practice is omitted from administra

4

tive adjudication, compensating safeguards are all the more

necessary. The challenged regulation, however, far from

compensating for procedural deficiencies, compounds them,

by eliminating nearly all of them. It provides an informal

proceeding appropriate for ordinary social worker-client

relationships, but totally inappropriate when the client and

the welfare department have become adversaries. Welfare

aid is usually withheld or terminated because of changed

circumstances about which there is no disagreement. Rele

vant here, however, are those cases in which the recipient

denies an alleged change of circumstances. This is usually

no mere misunderstanding that can be cleared up by in

formal conferences among people of good will with common

interests. It is a dispute about facts, the resolution of which

has the profoundest consequence for the recipient. The tra

ditional procedures that have developed in our courts are

still the best way, and the only constitutional way, to assure

justice to all parties in adversary positions.

The following pages argue that the state has shown no

such compelling public necessity as would justify the pro

cedural inadequacies of the challenged regulation. In the

McCullough* case, in a motion before the California Court

of Appeal, California’s Attorney General has expressly

stated that costs are not in issue. (See Appendix C.) Other

public interests, such as administrative convenience, are

hardly “ compelling” .

The argument continues to show that three days notice

provided for by the challenged regulation is insufficient to

permit a recipient to prepare his case; that without subpoe

na power, and without the right of confrontation and cross-

5

#See footnote 1, p. 1, supra, and text thereto.

examination, a hearing is not an adjudicatory procedure,

but only a tool of discovery; that without a record, the per

son who decides must decide on the basis of matters outside

the record and may decide on a version of the evidence

different from that which the recipient confronted; that the

unnamed person in the welfare department who must de

cide is likely to be partial, not impartial; and that in per

mitting discontinuance of aid on the ground of “probable

ineligibility” rather than “ ineligibility” California author

izes a drastic result on vague and inadequate grounds.

Lastly, this brief argues that the California statute and

ease law may require even greater protection for the re

cipient than the United States Constitution, and, a priori,

can require no less. The California Welfare and Institutions

Code permits aid to be cancelled, suspended or revoked

only “ for cause” or “ after investigation.” Previous Cali

fornia interpretations of analogous language show that such

language requires a hearing with all the usual procedural

safeguards the word implies.

ARGUMENT

I. The Notice and informal Conference Provided by the Chal

lenged Regulation Prior to Termination ©f Benefits by a County

Welfare Department Do Not Afford the Protections Required

by Due Process.

The District Court held that the informal conference pre

scribed by PSS 44-325.43 is a constitutionally adequate

“hearing” prior to termination of benefits, in the light of

subsequent “ fair hearing” requirements. This decision not

only conflicts with the decision in Kelly v. Wyman (S.D.

N.Y. 1968) 294 F. Supp. 893, probable jurisdiction noted,

sub. nom Goldberg v. Kelly, 37 LW 3399, but with basic

constitutional principles.

6

An erroneous decision to terminate aid to a welfare

recipient is disastrous to the individuals affected. Under

California Welfare and Institutions Code (hereinafter re

ferred to as W. & I. Code) Sections 10950 et seq. the review

of such a decision does not stay its effect, and the review

takes two months or longer. Since most recipients are under

an incapacity which prevents them from supporting them

selves (e.g. blindness, old age, infancy or medical disability)

they will not have minimum subsistence for this period.

The existence of a hearing subsequent to termination, there

fore, affects neither the importance of the prior decision

nor its basic adjudicatory character.

As a general rule, due process requires that such a deci

sion be made in accordance with “ procedures which have

traditionally been associated with the judicial process.”

Hannah v. Larche (1960) 363 U.S. 420, 442. These pro

cedures have been held to include adequate notice, Russell-

Newman Manufacturing Go. v. N.L.R.B. (1966) 370 F.2d

980; see, Hornsby v. Allen (1964) 326 F.2d 605, 608; the

right to confrontation and cross-examination, Greene v.

McElroy (1959) 360 U.S. 474; Willner v. Committee on

Character and Fitness (1963) 373 U.S. 96; a decision based

on evidence produced at a hearing, Ohio Bell Telephone

Co. v. P.TJ.C. (1936) 301 U.S. 292; English v. City of Long

Beach (1950) 35 C.2d 155, 217 P.2d 22; an impartial trier

of fact, Wasson v. Trowbridge (1967) 382 F.2d 807; In re

Murchison (1955) 349 U.S. 133; and a decision on the merits,

Endler v. Schutzbank (196S) 68 C.2d 162, 436 P.2d 297.

Occasionally, where there is a compelling public inter

est involved, one or more of these elements may be con

stitutionally omitted. Absent considerations of compelling

public necessity, however, due process requires the preser

vation of all the elements of an adjudicatory proceeding

7

necessary for the protection of the interests affected. Cafe

teria and Restaurant Workers v. McElroy (1961) 367 U.S.

886; Sokol v. Public Utilities Commission (1966) 65 C.2d

247, 418 P.2d 265; Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Educa

tion (5 Cir. 1961) 294 F.2d 150. As is shown immediately

below, there is no compelling public interest or other justi

fication for the procedural inadequacies of the regulation.

Thus, the hearing preceding the termination of aid to a

welfare recipient must preserve all the traditional elements

of the adjudicatory process. The regulation preserves none.

A. THERE IS NO COMPELLING PUBLIC NECESSITY OR OTHER JUSTIFICA

TION FOR THE PROCEDURAL INADEQUACIES OF THE REGULATION.

The District Court does not specify what public interest

it relies on to justify the obvious procedural deficiencies in

the regulation. Mere administrative inconvenience to the

state or counties, certainly, cannot justify the sacrifice of

safeguards required by due process. Ohio Bell Telephone

Company v. Public Utilities Com. (1937) 301 U.S. 292, 304-

305; Endler v. S chut shank (1968) 68 C.2d 162, 180, 436

P.2d 297. Since adequate hearings are already provided

after action is taken, it can hardly be claimed that the pro

vision of such hearings prior to action would impair the

ability of the state and county departments from carrying

out the functions for which they are responsible.

Perhaps of ultimate concern to the State is the question

of cost.2 By providing for an ex parte determination of

2. In the case of McCulhugh v. Terzian, in the California Court

of Appeal, the Attorney General of California filed a memorandum

(Appendix C) opposing the introduction of additional evidence in

that court, stating that “ cost to the State has not been put in issue.”

The additional evidence offered was admittedly incomplete hut

tended to show that costs to the State resulting from the State-wide

order of the trial court was not significant.

8

probable ineligibility without any provision for contesting

that determination on its merits in a meaningful hearing

prior to the withdrawal of benefits, the State Department

of Social Welfare is obviously attempting to minimize the

cost of paying welfare benefits to persons who maj ̂ not in

fact be eligible. In so doing they have apparently deter

mined that it is more important to protect the public purse

than it is to protect the public reputation for justice. While

it is of course important to preserve public funds, consti

tutional rights cannot be sacrificed in the process. Edwards

v. California (1941) 314 U.S. 160.

Furthermore, the costs thus saved will not be great. Under

the judgment of the California Superior Court in McCul

lough* for example, the continued payment of benefits

pending an adequate hearing is available only to a person

who controverts the allegations of ineligibility in a sworn

statement and requests a “ fair hearing” . Payment of bene

fits to these persons pending an adequate hearing causes

the State no financial injury at all if the recipient is found

eligible, since binding federal regulations require payment

of aid retroactively to the date of discontinuance. Federal

Handbook of Public Assistance Administration (Federal

Handbook), Sections 6200 (k), 6300 (g). Furthermore, aid

payments pending hearing are explicity sanctioned under

regulations enacted pursuant to the Federal Social Security

Act. (Federal Handbook, Section 6500 (b )). Under these

circumstances, amicus submits that the regulation fails to

provide a hearing “ at a meaningful time and in a meaning

ful manner” which due process requires. Armstrong v.

Manso (1965) 380 U.S. 545, 552.

*See footnote 1, p. 1, supra, and text thereto.

10

B. A DECISION TO TERMINATE CATEGORICAL AID BENEFITS IS AN AD

JUDICATORY ACT, REQUIRING, AS A MINIMUM, ADEQUATE NOTICE,

OPPORTUNITY FOR CONFRONTATION AND CROSS-EXAMINATION, A

DECISION BASED ON EVIDENCE PRODUCED AT A HEARING, AN IM

PARTIAL TRIER OF FACT, AND A DECISION ON THE MERITS. THE

CHALLENGED REGULATION PROVIDES NONE OF THESE.

A decision to withdraw benefits must be based on a de

termination that a recipient previously found eligible for

such benefits is no longer eligible. In contested cases, such

a determination requires the resolution of disputed factual

issues and the application of detailed statutory and regu

latory criteria and is therefore an adjudicatory act. See

Hornsby v. Allen (5 Cir. 1964) 326 F.2d 605, 608. It there

fore requires the elementary safeguards which the chal

lenged regulation fails to provide. 326 F.2d at 608.

T. The regulation fails to provide adequate notice.

It is elementary that due process requires notice of

charges sufficiently in advance of hearing to permit ade

quate preparation for a hearing. Russell-Newman Manu

facturing Company v. N.L.R.B. (5 Cir. 1966) 370 F.2d 980 ;

see Hornsby v. Allen, (5 Cir. 1964) 326 F.2d 605.

PSS 44-325.43 provides that a recipient shall be notified

of a decision to withhold categorial aid benefits and the

grounds therefor at least three days before aid is actually

withheld. It further provides that the recipient shall be

informed of the evidence on which such a decision is based

at an informal conference which is the recipient’s sole

opportunity to contest the county’s action before it takes

effect.

The evidence presented to the recipient for the first time

at the conference may be overwhelming in detail and may

be in a form so general or unorganized that it would he

difficult to refute under any conditions. To do so imme

diately after first notice is often impossible. Even if the

county’s evidence is made available to the recipient prior

11

to the conference, three days is manifestly too short a

time to permit adequate preparation. In this briefest of

periods, the recipient who receives notice of proposed termi

nation must gather and present evidence to rebut a report

which professional investigators had a month or longer

to prepare.3 He is called upon to secure legal counsel, dis

cover and evaluate the factual and legal grounds for the

proposed termination, contact the county department to

schedule an informal conference, interview adverse and

favorable witnesses and arrange for their presence at the

conference (without the benefit of subpoenas), and secure

relevant documentary evidence, such as medical reports

or wage records (again without the benefit of subpoena

power). If all this is not adequately accomplished in a

period as short as three days, there will be no chance of

disturbing the ex parte determination of ineligibility and

benefits will be withheld. In these circumstances the right

to counsel is illusory.

The regulation involved in Kelly v. Wyman (S.D.N.Y,

1968) 294 F. Supp. 893, probable jurisdiction noted, sub

nom Goldberg v. Kelly, (1969) 37 LW 3399, required seven

days written notice prior to the proposed effective date

of the discontinuance. The District Court in that case

deemed such notice mailed seven days before effective date

adequate. This is one of the most important distinctions

between the New York and California regulations.

While three days may provide notice of proposed action,

it clearly does not provide an adequate opportunity to con

3. The record in McCullough (see footnote 1, supra, p. 1)

shows that the investigation by the District attorney’s office of Mary

McCullough’s eligibility lasted at least 36 days. On February 15,

1968, the man alleged to be living with Mrs. McCullough was inter

viewed, C.T. 73, and the supplement summarizing the statements of

two witnesses is dated March 21, 1968. C.T. 75. This length of time

is not exceptional.

test the validity of that action. The California regulation

provides a tool of discovery rather than an adjudicatory

proceeding.

32

2. The regulation provides no opportunity to test the credibility and probative

value of evidence.

Even if the regulation permitted adequate time to pre

pare for the conference, it would he constitutionally in

adequate because its failure to provide subpoena power or

the power to administer oaths deprives both the county

and the affected recipient of any opportunity to test the

credibility and probative value of the evidence on which

a decision to terminate benefits is based.

Complex factual determinations, such as whether a hus

band and wife are disassociated or have abandoned a child,

whether a man has lived with a woman in a spouse-like

relationship, or whether a person is physically or psycho

logically unemployable, are a necessary element in many

decisions to withhold public assistance benefits. Where, as

here, such fact findings serve as a predicate for govern

mental action which seriously injures an individual, con

frontation and cross-examination are an indispensable ele

ment of a hearing. Greene v. McElroy (1959) 360 U.S. 474,

507; Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitness (1963)

373 U.S. 96. See, Walker v. City of San Gabriel (1942) 20

C.2d 879,129 P.2d 349.

Under the regulation, however, a determination of in

eligibility must be made on the basis of evidence which is

primarily hearsay, circumstantial and untested opinion.

“ [N]ot only is the testimony of absent witnesses allowed

to stand without the probing questions of the person under

attack which often uncover inconsistencies, lapses of recol

lection, and bias, but in addition, even [county personnel]

do not see the informants or know their identities, but

normally rely on an investigator’s report of what the in

formant said without even examining the investigator per

sonally.” Greene v. McElroy (1959) 360 U.S. 474, 497-499

(footnotes omitted). Without the ability to require the

attendance of witnesses and to take sworn testimony, a

trier of fact has no rational or adequate method of weigh

ing conflicting testimony and therefore cannot render a

meaningful decision.

3. The regulation fails to require a decision based on evidence produced at

a hearing.

A decisional process which permits a determination to

be made on the basis of evidence heard ex parte is mani

festly inadequate to protect the affected party against arbi

trary action. Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. P.TJ.C. (1937) 301

U.S. 292. “ [T]he requirement of a hearing necessarily

contemplates a decision in light of evidence there intro

duced.” English v. City of Long Beach (1950) 35 C.2d 155,

159, 217 P.2d 22, 24.

The regulation provides an opportunity for the recipi

ent “ to learn the nature and extent of the information on

which the withholding action is based” and “ to provide an

explanation or information.” However, it does not provide

the recipient with the right to present any such explana

tion or information to the person or persons responsible

for rendering the ultimate decision, nor does it require

that a record of the evidence be made and transmitted to

the decision maker. Presumably the substance of the coun

ty’s evidence and the recipient’s “ explanation or informa

tion” must be communicated to the person who decides.

This material may be transmitted in such a manner as to

destroy its worth altogether. Elements may be omitted,

distorted or colored in the retelling. The version that ulti

mately reaches the trier of fact may be incomplete or in

13

14

accurate, and may be quite different from the version that

confronted the recipient at the informal conference.

Under these circumstances the opportunity offered by

the regulation to “ provide an explanation” offers no

meaningful opportunity to present evidence and cannot be

deemed to satisfy due process. See, I.C.C. v. Louisville &

N. B. Co. (1912) 227 U.S. 88, 91; Dixon v. Alabama State

Board of Education (5 Cir. 1961) 294 F.2d 150.

4. The regulation fails to provide an impartial trier of fact.

Even if a recipient were afforded adequate notice and

the right of confrontation and cross-examination, the fail

ure of PSS 44-325.43 to require a decision by a person

having no prior direct involvement in the case renders it

inadequate to provide the protection required by due

process.

It is too clear to require argument or extended citations

that a fair hearing presupposes an impartial trier of fact

and that prior official involvement renders impartiality most

difficult to maintain. Wasson v. Trowbridge (1967) 382

F.2d 807, 813. Under the regulation, an affected recipient

is entitled only to a conference with his caseworker or other

unspecified county personnel who not only may have been

involved in prior aspects of his case, but who may have

actually made the initial recommendation to withhold bene

fits. The court in Kelly v. Wyman, supra, 294 F. Supp. 893,

906 construed a regulation which provided:

“ Only the social services official or an employee of his

social services department who occupies a position

superior to that of the supervisor who approved the

proposed discontinuance or suspension shall be desig

nated to make such a review.”

The court said that, if in practice the reviewing official were

a case supervisor who had been consulted in advance for

15

approval of proposed terminations or who might even have

initiated the recommendation to terminate, it would be a

clear violation of the spirit of the New York regulation.

294 F. Supp. at 907. The California regulation does not even

attempt to require the decision maker to be a superior of

the one who made the initial decision. It leaves the position

of the decision maker completely unspecified. In fact, in

relatively small county welfare departments there may be

only one superior in the department, so that he will un

doubtedly be the one who made the preliminary decision.

Thus, the California regulation cannot be construed so as

to be constitutional, unlike the New York regulation.

To illustrate the application of the California regulation,

in the case of Mrs. McCullough (one of the plaintiffs in

the California State Court action*), after receiving the

investigation reports of the Family Support Division of

the District Attorney’s office, the social worker for Mrs.

McCullough, along with her supervisor, determined that

her continued eligibility for welfare benefits was condi

tioned on her admission that she was and had been living

with a man whose income would have to be considered in

determining her grant. C.T. 51-52. The social worker then

visited Mrs. McCullough, discussed the investigator’s re

port with her, and advised her that if she admitted that

the man in question was living with her, her grant would

be adjusted in accordance with his income, but that if she

denied it, aid would be discontinued. Mrs. McCullough de

nied the allegation and two days later she was notified that

her case was being discontinued, “because of failure to pro

vide essential information” . C.T. 52. Although she had the

right, before termination became effective, to again discuss

*See footnote 1, p. 1, supra, and text thereto.

the matter with her social worker, there was no right to

independent review by any person not previously connected

with the case. Instead of initiating an impartial review of

the facts, her denial terminated her right to further bene

fits. The “hearing” provided by the regulation is no more

than the opportunity to dissuade a person who has already

decided (and who may have a vested interest in supporting

that decision). Impartiality and fairness under these cir

cumstances may not only he difficult, but impossible to

maintain.

16

5. The regulation fails to require a decision on the merits.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the regulation

does not require a decision on the merits but permits the

county to withhold benefits upon the receipt of evidence

“which is both substantial in nature and reliable in source

. . . indicating . . . probable ineligibility” , PSS 44-325.421

(Emphasis added; set forth in Appendix A.)

Not only is it incumbent upon the county to withdraw

benefits upon a determination of probable ineligibility but

it is required to do so as soon as possible. PSS 44-325.1

(Set forth in Appendix A ). Under these circumstances a

county may withhold benefits without regard to the con

tradictory evidence offered by a recipient, thereby leaving

the ultimate decision on the merits to the subsequent hear

ing conducted by the State Department of Social Welfare.

The only place in our system of justice where such a pro

ceeding is deemed permissible is in the area of law enforce

ment or where the public health or safety is endangered.

Sokol v. Public Utilities Commission (1966) 65 C.2d 247,

418 P.2d 265; North American Cold Storage Company v.

City of Chicago (1908) 211 U.S. 306. Even in those circum

stances there are a variety of devices available to prevent

or mitigate the injury which may flow from the necessity

of taking governmental action before there has been a full

hearing on the merits, such as bail, release on own recogni

zance, preliminary hearings, etc. There are no devices for

mitigating the damage herein or for staying the govern

mental action and there is no threat to the public safety

involved.

In light of the vital interest of public assistance recipients

in an adequate hearing prior to withdrawal of benefits and

of the absence of any significant interest of the County or

State to the contrary, amicus submits that the termination

procedures of PSS 44-325.43 are “ inconsistent with rational

justice, and [come] under the Constitution’s condemnation

of all arbitrary exercise of power.” I.C.G. v. Louisville &

N. B. Co. (1912) 227 U.S. 88, 91.

C. THE AVAILABILITY OF A SUBSEQUENT HEARING DOES NOT JUSTIFY

THE ELIMINATION OF AN ADEQUATE PRIOR HEARING.

The District Court opinion implies that the procedural

safeguards obviously omitted from the regulation are not

constitutionally required prior to the termination of bene

fits because a fair hearing is available afterwards. The law

is clearly to the contrary. Absent come compelling public

interest, due process requires procedural safeguards ade

quate to protect the interest affected prior to action.

This Court most recently reaffirmed this proposition in

Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp. (1969) .........U.S.............,

37 LW 4520.

Two California cases are likewise instructive on the ne

cessity of a hearing prior to the time action takes effect,

despite subsequent procedures. Mendoza v. Small Claims

Court (1958) 49 C.2d 668, 321 P.2d 9; Sokol v. Public Utili

ties Commission (1966) 65 C.2d 247, 418 P.2d 265.

17

At issue in Mendoza was whether a month-to-month ten

ant could he deprived of possession pursuant to a small

claims court judgment where there had been no right to

counsel. The California Supreme Court unanimously held

that he could not; and that therefore a statute vesting juris

diction of unlawful detainer actions in small claims courts

violated due process because it contained no provision for

an automatic stay on appeal and the tenant could be dis

possessed before the appeal was determined. The small

claims hearing, which is an informal trial before a judge

on adequate notice, California Code Civ. Proe., Sec. 117 et

seq., was deemed inadequate to permit dispossession of the

tenant despite the appeal right to a subsequent trial de novo

with counsel.

In Sokol the interest of a telephone subscriber in avoiding

a temporary interruption of service was at stake. The opin

ion held unconstitutional a regulation which permitted dis

connection of telephone service on the basis of a police alle

gation that it was being used illegally and which provided

a hearing only after service was terminated. The court

stated that at a minimum, due process requires that an

ex parte determination of probable cause be made by an

impartial tribunal prior to disconnection, and that the sub

sequent hearing be promptly provided. 65 C.2d 247, 250,

418 P.2d 265, 271.

In the instant case, there can be no impairment of a vital

gOAmrnment function, such as law enforcement, which was

involved in Sokol. On the other hand, the interest of a cate

gorical aid recipient in continued receipt of aid pending an

adequate hearing is far greater than the interest in con

tinuous telephone service and is at least as great as the

interest of the tenant in possession. The inability of the

wrongfully terminated categorical aid recipient to pay his

18

19

rent subjects him to an unlawful detainer suit to which he

will have no defense, and to subsequent eviction. Calif. Code

Civ. Proc., Sec. 1159 et seq. His inability to pay utility bills

will result in disconnection of telephone, gas and electricity.

Yet PSS 44-325.43 contains no provision under any circum

stances for a stay of decision pending an adequate hearing,

such as the California Legislature added to the statute after

Mendoza to render it constitutional. Calif. Code Civ. Proc.,

Sec. 117 j (Calif. Stats. 1959, ch. 1982, p. 4588) Therefore,

even when a recipient appeals in good faith, as evidenced

by the filing of the sworn statement required by the judg

ment in McCullough * the regulation permits termination

of his aid after a so-called “hearing” which provides far less

protection than a small claims trial before a judge, at issue

in Mendoza, and which does not even afford the most ele

mentary safeguard of an impartial tribunal which was re

quired to protect a far less vital interest in SoTcol.

So far as amicus can determine, no administrative agency

has ever been permitted to terminate an interest comparable

to that involved here under procedures so utterly lacking

in elementary safeguards.! Even if there are considerations

which permit the relaxation of one or more of the elements

discussed above, (pp. 10-17), no case has been discovered

which approves proceedings lacking all of these basic safe

guards.

“ For the guidance of the parties” , the court in Dixon v.

Alabama State Board of Education (5 Cir. 1961) 294 F.2d

150, 158, cert. den. 368 U.S. 930, set forth its views “ on the

*See footnote 1, p. 1, supra, and text thereto.

f Appendix B describes the rules of procedure governing proceed

ings which are used by a representative group of administrative

agencies in acting to revoke or suspend a license or privilege granted

to an individual.

nature of the notice and hearing required by due process

prior to expulsion from a state college or u n iv e rs ity (Em

phasis added). The views expressed were dictum and were

expressly limited to the facts of the particular case. They

are instructive however. The court specifically rejected the

idea that “ an informal interview with an administrative

authority” was a sufficient hearing prior to expulsion. While

it did not require a full trial-type hearing including the

right to cross-examine witnesses, this was because “ [s]uch

a hearing, with the attending publicity and disturbance of

college activities, might be detrimental to the college’s edu

cational atmosphere and impractical to carry out.” 294 F.2d

at 159.

It hardly needs to be stated that categorical aid recipients

are not subject to the same disciplinary requirements as

college students, (see Parrish v. Civil Service Commission

(1966) 66 C.2d 260, 425 P.2d 223) and that an adequate

hearing provided before termination of benefits will entail

no disruption of the Welfare Department’s functions. The

receipt of categorical aid benefits pending a hearing cannot

be dismissed as a lesser interest than attendance at a tax

supported college.

On the other hand, considered essential by the Dixon

court were: notice containing a statement of the specific

charges and grounds, a report to the student including the

names of all witnesses and the facts to which they testify,

an opportunity to hear both sides in considerable detail

including an opportunity to present a defense with oral

testimony and written affidavits, and a report on the findings

of the hearing. In short, the court suggests that the rudi

ments of an adversary system should be preserved as much

as possible without encroaching upon the legitimate interest

of the governmental agency involved.

20

21

It simply makes sense that where one element of judicial

practice has been omitted from administrative adjudica

tions, the provision of compensating safeguards is all the

more necessary. I.C.C. v. Louisville & N. R. Co. (1912) 227

U.S. 88, 93; Shively v. Stewart (1966) 65 C.2d 475, 480, 421

P.2d 65.

It is sometimes suggested that welfare recipients are not

entitled to the same due process as other more fortunate

citizens because there is no constitutional right to receive

such assistance.

Whether or not there exists a vested right to public

assistance benefits, the requirements of procedural due

process must be met before such benefits may be with

drawn. Courts have explicitly rejected the view that ade

quate procedural safeguards are required only when vested

or constitutional rights are at stake and have required

hearings to protect the interest of a student in remaining

in a tax-supported university, Dixon v. Alabama■ State

Board of Education (5 Cir. 1961) 294 F.2d 150, 156; Gold

berg v. Regents of the University of California (1967) 248

C.A.2d 867, 57 Cal. Rptr. 463; the interest of an applicant

for or holder of a business license; Hornsby v. Allen (5

Cir. 1964) 326 P.2d 605, 609; Fascination Inc. v. Hoover

(1952) 39 C.2d 260, 269, 246 P.2d 656, 661; one’s interest

in employment, Slochower v. Board of Education (1956)

350 U.S. 551; Greene v. McElroy (1959) 360 U.S. 474; and

one’s interest in doing business with a government agency

Gonzalez v. Freeman (D.C. Cir. 1964) 334 F.2d 570, 574. As

the court stated in Cafeteria and Restaurant Workers v.

McElroy (1961) 367 U.S. 886, 894, “ One may not have a con

stitutional right to go to Baghdad, but the Government may

not prohibit one from going there unless by means con

sonant with due process of law.”

Under California law, categorical aid benefits must be

administered promptly and humanely. W & I Code Sec.

10000. Due process requires no more. Although the fair

hearing provided by the state to review county action may

satisfy the requirement of statewide supervision, W & I

Code Sec. 10600, it comes too late to satisfy the require

ment of due process. The state is fully able to provide pro

tection more meaningful than that provided under present

practice. It can either require an adequate hearing on the

county level or provide for a stay of the county’s decision

pending the state “ fair hearing.” It does neither, but in

stead permits benefits to be withdrawn after nothing more

than a summary ex parte determination and an illusory

opportunity to dissuade afterwards. It seeks to minimize

costs rather than injustice. By so doing it can only further

the alienation of society’s most disadvantaged persons

from their Government and the alienation of their Gov

ernment from its founding principles. As stated by Jack-

son, J . :

“ Let it not be overlooked that due process of law is not

for the sole benefit of an accused. It is the best insur

ance for the Government itself against those blunders

which leave lasting stains on a system of Justice but

which are bound to occur on ex parte consideration.”

Dissenting opinion, Shaughnessy v. United States

(1953) 345 U.S. 206, 224-225.

II, The Notice and Informal Conference Provided by the Chal

lenged Regulation Prior to Termination of Categorical Aid

Benefits by a County WeSware Department D® Not Afford the

Protection Required by the California Legislature.

California conceded in McCullough* that the requirement

of the W & I Code that benefits under the categorical aid

22

#See footnote 1, p. 1, supra, and text thereto.

program may be withdrawn “ for cause” ! carries with it

the right to a hearing prior to actual withdrawal. (Appel

lant’s Opening Brief, page 16) Ratliff v. Lampton (1948)

32 C.2d 226,195 P.2d 792.

In Ratliff, the California Supreme Court held that a

statute authorizing the Department of Motor Vehicles to

revoke a driver’s license for good cause carried with it the

right to a hearing before the Department prior to revoca

tion despite provision in the statute for a subsequent hear

ing before the Director of the Department. The decision

rests on the rule, established in a series of prior cases, that

where an agency is required by statute to act for cause, an

affected party must be afforded a hearing prior to action

unless there is a clear showing of a contrary legislative

intent. Carroll v. California Horse Racing Board (1940)

16 C.2d 164, 105 P.2d 110 (suspension of horse trainer’s

license); La Prade v. Department of Water and Power

(1945) 27 C.2d 47, 162 P.2d 13 (civil service discharge);

Covert v. State Board of Equalization (1946) 29 C.2d 125,

173 P.2d 545 (liquor license revocation). The court in Ratliff

stated:

“ The fact that the Vehicle Code provided for an

administrative review subsequent to revocation does

not alter this rule. We should not imply legislative in

tent to deprive a person of his license without a prior

opportunity to be heard unless compelled to do so by

the plain language of the statute, regardless of whether

23

fThe county must have cause to cancel, suspend or revoke aid

in the Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Old Age Security,

and Aid to Blind programs. W & I Code Sec. 11458, 12200, and

12700 respectively. The provision of W. & I. Code See. 13750 per

mitting the county to cancel, suspend or revoke Aid to Disabled

Benefits “ after investigation” imposes the same hearing require

ment as the “ for cause” provisions of the other sections. See 'Steen

v. Board of Civil Service Commissioners (1945) 26 C.2d 716, 160

P.2d 816, “ The words ‘ hearing’ and ‘ investigation’ may mean the

same thing.” Ratliff v. Lampton (1948) 32 C.2d 226, 231, 195 P.2d

792, 795.

24

there is a right to administrative review after the revo

cation.” 32 C.2d at 230,195 P.2d at 795.

An identical statutory scheme manifests the Legisla

ture’s intent to require a hearing prior to action in the

instant case. The county is required to act for cause or

after investigation in terminating aid, and a hearing sub

sequent to action is provided before the Director of the

State Department of Social Welfare. W. & I. Code Sec.

10950 et seq.

The District Court held that PSS 44-325.43 meets the

requirement of a hearing prior to the withdrawal of bene

fits. The regulation provides that an initial decision to

withhold or terminate benefits is made by administrative

personnel in the County Department on the basis of evi

dence which is presented and reviewed ex parte and which

may be totally hearsay, circumstantial or untested opinion.

It permits the county to give the affected recipient as little

as three days’ notice of the decision to withdraw benefits

and requires that the caseworker, an eligibility worker or

other unspecified person in the county department be avail

able for an informal conference with the recipient. At the

conference, the recipient is confronted for the first time

with the evidence on which the withholding action is based

and may provide any explanation or information he may

wish in support of his eligibility. The decision to withhold

benefits takes effect automatically unless as a result of the

informal conference or on some other ground, the county

department reverses itself. It is clear from Ratliff and the

cases on which it relies that the statutory requirement that

welfare benefits be terminated for cause carries with it the

right to a procedurally adequate hearing prior to with

drawal of benefits regardless of the existence of subsequent

review.

Steen v. Board of Civil Service Commissioners, (1945)

26 C.2d 716, 160 P.2d 816, and the other eases relied on in

Ratliff, established beyond doubt that when an agency may

act for cause only, it must provide a hearing subject to the

procedural and evidentiary rules normally associated with

the term and not left to the unfettered discretion of the

agency.

In Steen, the court specifically disapproved a statement

in a prior case that the conduct of a hearing and the class

of evidence to be heard were matters of administrative dis

cretion and that nothing more was required than that the

affected party ‘‘be permitted to produce his evidence” . The

court stated that this was too permissive and that “ a hear

ing is required with all that the term implies” , where a

board is required to “ investigate” a civil service discharge.

26 S.2d at 725,160 P.2d at 821.

As to the evidence required to support an administrative

determination of cause, three of the cases principally relied

on in Ratliff cite the rule established in Walker v. City of

San Gabriel (1942) 20 C.2d 879, 129 P.2d 349, that hearsay

alone cannot support an administrative decision. Steen v.

Board of Civil Service Commissioners (1945) 26 C.2d 716,

727; 160 P.2d 816, 822; La Prade v. Department of Water

and Power (1945) 27 C.2d 47, 51; 162 P.2d 13, 15; Covert v.

State Board of Equalisation (1946) 29 C.2d 125, 1.73 P.2d

545. The court in Steen ruled that the petitioner was denied

a hearing where the only evidence introduced in support

of the administrative decision was an unsworn and unveri

fied investigation report. 26 C.2d at 727, 160 P.2d at 822.

In La Prade, supra, the court stated that even if an

investigation report is competent evidence, no hearing is

had unless the report “ is introduced into evidence and the

accused is given an opportunity to cross-examine the maker

thereof and refute it.” 27 C.2d at 52,162 P.2d at 16.

25

Although the court in Ratliff, supra, indicated that the

hearing prior to action might be less formal than the sub

sequent hearing, it did not sanction a conference subject

to no procedural or decisional rules whatever. Procedures

virtually identical to those provided by PSS 44-325.43 were,

as a practical matter, undoubtedly available in Ratliff also,

since the statute required ten days notice prior to the

revocation of a license. During this period, administrative

officials were presumably available and willing to inform

the licensee of the basis of their proposed action and to

listen to any explanation or information he wished to pro

vide. Yet it was not even contended that the opportunity

for informal review afforded by the ten-day notice period

constituted the hearing required by statute.

The use of an informal conference to meet a statutory

requirement that administrative action be “ for cause only”

was specifically rejected in Keenan v. 8.F. Unified School

District (1950) 34 C.2d 708, 214 P.2d 382. The court stated

that “ informal interviews with administrative officers . . .

did not constitute a hearing contemplated by the statute.”

34 C.2d at 715, 214 P.2d at 386.

PSS 44-325.43 provides no more than the informal inter

view with administrative personnel which was specifically

found not to be a hearing in Keenan and which was pre

sumably available with an even greater notice period in

Ratliff. It permits a decision of ineligibility to be rendered

solely on the basis of an investigator’s hearsay report,

which California courts have consistently held to be a denial

of a hearing. Walker v. City of San Gabriel (1942) 20 C.2d

879, 129 P.2d 349; Steen v. Board of Civil Service Commis

sioners (1945) 26 C.2d 716, 160 P.2d 816; La Prade v.

Department of Water and Poiver (1945) 27 C.2d 47, 162

P.2d 13. In failing to specify the nature of the conference,

the regulation vests in the county the same unlimited dis-

26

27

cretion which Steen specifically disapproved. Far from

meeting the requirements of a hearing under California

law, the regulation exhibits the same defects which have

rendered other procedures inadequate to meet statutory

requirements identical to those presented here.

Further indicative of the legislative intent to require

greater safeguards than the regulation provides prior to

termination is the length of time permitted by statute for

the rendition of the state “ fair hearing decision” . Although

newly adopted regulations of the State Department of

Social Welfare require such a decision within sixty days

after the hearing, (Operations Manual, 22-043 through 22-

065, (see also, Federal Handbook § 6200(j )), the Legisla

ture has explicitly permitted 180 days to elapse before such

a decision is rendered. W.&T. Code Sec. 10950 et seq. The

length of this statutory time limit provides a clear indica

tion that in requiring cause for the withdrawal of benefits,

the Legislature must have intended to provide a hearing

fully adequate to protect the aid recipient during the six

months permitted for subsequent review.

The hearing required by statute may afford greater safe

guards than due process requires. In Ratliff v. Lampton,

(1948) 32 C.2d 226, 232, 195 P.2d 792, 796, the court specifi

cally stated that while the summary revocation of a driver’s

license might be constitutionally permissible, this “ cannot

be used to imply a legislative intent to deny [the right to a

hearing] before the revocation.” Later the Constitution was

held not to require a hearing, Escobedo v. State of Cali

fornia (1950) 35 C.2d 870, 222 P.2d 1, leaving Ratliff to

stand for the proposition that “ for cause” in a statute means

more than “ due process” in the U.S. Constitution.

28

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons this Court should reverse the

judgment of dismissal rendered by the District Court as to

the class. It should make clear that informal procedures

have a place in the system, but that such procedures deny

due process when a proceeding has become adversary in

nature. It should make clear that aid to welfare recipients

may not be terminated or withheld without an adequate

hearing, and that such a hearing must include all the safe

guards that are customarily available in adjudicatory pro

ceedings, including adequate notice, right to counsel, con

frontation and cross examination, a record of the evidence,

a decision based on the evidence by an impartial person,

and a decision on the merits.

Dated,

Oakland, California, June 20,1969

Respectfully submitted,

T homas L. F ike

T homas Schneider

Burton Danziger

David Nawi

A ttorn eys fo r Am icus Curiae,

L egal A id S ociety o f

Alam eda County

(Appendices follow)

Appendix A

CALIFORNIA STATE HIPARTMiNT

OF SOCIAL WELFARE

PUBLIC SOCIAL SERVICES MANUAL

REGULATION 44-325

AB

ATD

GAS

AFDC

AFDC

ATD

AB

ATD

GAS

AFDC

44-325 CHANGES IN AMOUNT OF PAYMENT 44-325

.1 W hen Change is E ffective

Whenever any change in the circumstances requires a

change in grant, or a discontinuance of aid the appro

priate change or discontinuance is to be made effective

as soon as possible. (See Sections 44-333.12, Adjustment

Period, and 44-331.1, Adjustment of Underpayment by

Authorization of Retroactive Aid.)

.11 If the change in the aid payment (as determined

in accord with PSS Section 44-315.5), amounts to

less than $2 per month, such change is not to be

made.

.12 D ecrea se: Where the required change is a decrease

of $2 or less, it shall be effective not later than the

second month following that in which the changed

circumstances were reported, and no adjustment is

to be made for overpayment of $2 or less in the

month of reporting or in the following month.

.13 In crea se: When the change in circumstances will

continue for only one or two months, and the amount

of the increase would be $2 or less, no change is

made in the continuing authorization.

.2 Change in Incom e or N eed

.21 Change and Am ount K now n in A dvance

If a change in income or need, including the amount,

is known in advance, any necessary change in the

amount of payment is made effective with the month

in which the changed circumstances will occur.

Appendix A

Appendix

.22 Change K now n in A dvance But Am ount N ot K now n

.221 Concurrent Paym ent and B udget P eriods

When it is known that income will start in the

next month but the exact amount is not known,

or when income is variable in amount, an

estimate of the expected income shall be made,

on the basis of available information, for the

purpose of determining the next current month

aid payment. If the estimate indicates ineligi

bility for any grant, aid may be withheld pend

ing verification of actual income (see Section

.421 below). I f the estimated income proves to

be incorrect when actual income is reported,

corrective action is taken to adjust the pay

ment within the limitations of PSS Sections

44-331 and 44-335.

.222 B udget Planning P eriod with Subsequent P a y

m ent P eriod

Actual income received in the Planning Period

is reported and reflected in the subsequent

payment.

Discontinuance

If a recipient’s circumstances change to the extent that

he no longer meets the eligibility7 requirements, aid

shall be discontinued effective the last day of the month

for which the last payment was made. (See PSS Sec

tion 44-315 re appropriate action when the recipient is

no longer eligible to a cash grant but remains eligible

to medical assistance as a medically needy person.)

W ithheld Paym ent

.41 Withheld Payment—Defined

A withheld payment is one which is held beyond the

usual delivery date while information concerning

AB

ATD

OAS

AFDC

Appendix 3

needs, income or basic eligibility is investigated,

subject to Section 44-325.43.

.42 Limitations on and Requirements for Withholding

of Aid Payment

Subject to the following limitations, aid payments

shall be withheld when further investigation is

necessary to determine continuing eligibility.

.421 Recipients should have the assurance of regu

lar and continued aid payment without inter

ruption or delay. Accordingly, an aid payment

may be withheld beyond the usual delivery

date only when evidence which is both sub

stantial in nature and reliable in source is

received by the county, indicating:

a. Probable ineligibility of the recipient, or

b. A probable overpayment has occurred or is

occurring which can be adjusted only if aid

payment is withheld.

.422 Aid payment shall not be withheld pending

ascertainment of increases in federal benefits

such as social security or increases in benefits

payable by a public agency. (W&IC Section

11014.)

.423 Aid payment shall not be withheld because of

actual or probable changes in need or income

when it appears that any resulting overpay

ment can be adjusted in the grant(s) for a

subsequent month or months. (See PSS Sec

tion 44-335.) (I f a recipient will be disadvan

taged by delaying the adjustment another

month, the county should discuss with the

recipient the desirability of an immediate cur-

4 Appendix

rent cash adjustment for the overpayment in

lien of the delayed grant adjustment.)

.424 An initial payment shall not he withheld be

yond the month for which it was authorized.

.425 The first installment of a month’s A F D C aid

payment may be withheld if the county’s eval

uation of circumstances indicates probable

ineligibility. If the question cannot be resolved

by the end of the first semi-monthly period

following that in which it arose, the second

payment is always withheld.

Unless the first installment o f a month’s aid

paym ent has been withheld, the second install

ment is n ever withheld excep t w hen:

a. Probable or actual ineligibility fo r the first

installment was discovered too late to hold

that paym ent, or

b. Probable overpaym ent is occurring which

can be adjusted only i f the second install

ment is withheld or i f the recipient would

be seriously disadvantaged by the delayed

adjustment.

F o r counties on the Subsequent Paym ent Plan

the second installment is n ever withheld be

cause o f changes occurring within the current

paym ent period.

AB

ATD

OAS

AFDC

.43 N otification to R ecipien t W hen Aid, Paym ent is

W ithheld

The recipient, the parent or other person respon

sible for the child in A F D C , shall be notified, in

writing, immediately upon the initial decision being

made to withhold a warrant beyond its usual deliv-

Appendix 5

ery date for any reason other than death, and in

no case less than three (3) mail delivery days prior

to the nsnal delivery date of the warrant to the

recipient. The county shall give such notice as it

has reason to believe will be effective including, if

necessary, a home call by appropriate personnel.

Form ABCD 239, Notice of Action, or a substitute

form, may be used for this purpose. Every notifi

cation shall include:

.431 A statement setting forth the proposed action

and the grounds therefor, together with what

information, if any, is needed or action re

quired to re-establish eligibility or to deter

mine a correct grant.

.432 Assurance that prompt investigation is being

made; that the withheld warrant will be de

livered as soon as there is eligibility to re

ceive it; and that the evidence or other infor

mation which brought about the withholding

action will be freely discussed with the re

cipient, parent, or other person, if he so de

sires (see Section .434 below).

.433 A statement of whether, if aid is withheld,

the recipient will or will not continue to be

certified for medical assistance during the

month aid is withheld.

.434 A statement that the recipient, parent, or

other person may have the opportunity to

meet with his caseworker, an eligibility work

er, or another responsible person in the county

department, at a specified time, or during a

given time period which shall not exceed three

6 Appendix

(3) working days, and the last day of which

shall be at least one (1) day prior to the

usual delivery date of the warrant, and at

a place specifically designated in order to

enable the recipient, parent, or other person:

(a) To learn the nature and extent of the in

formation on which the withholding action

is based;

(b) To provide any explanation or informa

tion, including, but not limited to that de

scribed in the notification pursuant to

Section .431 above;

(c) To discuss the entire matter informally

for purposes of clarification and, where

possible, resolution.

AB

ATB

OAS

AFDC

.44 Investigation and Time Limitations

.441 Evidence raising doubt concerning eligibility

or the correctness of grant is to be evaluated,

and any needed investigation initiated and

completed promptly, regardless of whether

there is basis for withholding an aid payment.

Such investigation must be completed and

appropriate action with respect to the grant

taken, within not more than 30 calendar days

after the date on which the information which

raised doubt concerning eligibility or the grant

was received by the county. (See Section 40-

155.2 regarding Methods of Investigation.)

.442 Aid payment for a second month may be with

held when the investigation is completed and

the facts regarding continuing eligibility or

AB

ATD

OAS

AFDC

Appendix 7

correctness of grant are established too late

in the 30-day period:

a. To permit any necessary discontinuance of

aid prior to the second month unless the

aid payment is withheld, or

b. To permit necessary adjustment in the aid

payment where eligibility continues but to

a lesser amount, and delay in the adjust

ment for another month would result in

overpayment which could not be adjusted.

When aid is withheld for a second month the

withheld warrants shall be reissued in the

correct amount and delivered to the recipient

within a maximum of ten calendar days fol

lowing the normal due date for the second

withheld warrant, or delivered to the recipi-

ient and a current cash adjustment obtained

from him. (See Section 44-333.12.)

.45 Action on Withheld Aid Payment Following Inves

tigation

.451 Investigation Establishes Recipient Eligible

to Receive Aid and That Withheld Payment

Was in Correct Amount.

The withheld payment shall be delivered im

mediately and aid payment continued. (If

the recipient was eligible on the first day of

the month aid shall be paid for the entire

month.)

.452 Investigation Establishes Eligibility but That

Aid should Be Paid in An Amount Less Than

the Withheld Payment.

AB

ATD

OAS

AFDC

Appendix

The withheld payment shall be delivered, pro

vided any resulting overpayment can be ad

justed within the adjustment period. In such

case at the time the withheld warrant is de

livered, the recipient shall be informed regard

ing the future grant adjustment(s) which must

be made. I f the resulting overpayment cannot

be adjusted in the adjustment period, the

withheld payment shall be canceled and re

issued and any indicated change made in the

continuing grant.

.453 Investigation Establishes Recipient Was In

eligible to Withheld Payment but Continues

Eligible to Aid.

The withheld payment is canceled and such

cancellation is not considered an interruption

in the authorization for payment.

.454 Investigation Establishes Ineligibility to

Withheld Payment and to Continuing Aid.

a. Aid was withheld because of probable in

eligibility.

Both the cash grant payment and certifi

cation for medical assistance are discon

tinued retroactively effective the last day

of the last month for which a cash grant

payment was made. The withheld cash

grant payment is canceled.

b. Aid was withheld solely for the purpose

of determining the amount of aid to which

the recipient was eligible but he subse

quently was found to be ineligible.

AB

ATD

OAS

AFDC

Appendix 9

There are two discontinuance dates both

which must be entered on the document

discontinuing aid.

The cash grant payment is discontinued

retroactively effective the last day of the

last month for which a cash grant payment