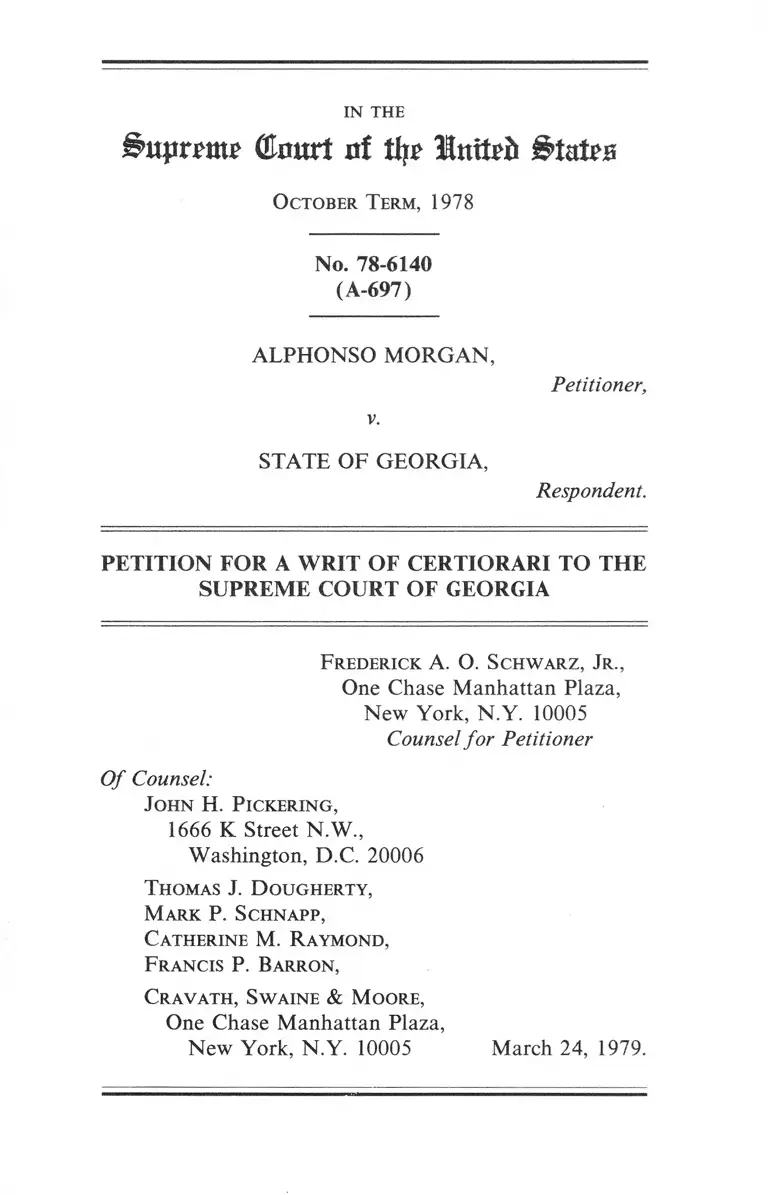

Morgan v. Georgia Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

Public Court Documents

March 24, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morgan v. Georgia Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia, 1979. 0d1eafba-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/59aa6467-8d5f-476c-b09c-050f7b866b39/morgan-v-georgia-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-georgia. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

CInurt rtf tljp llmti'ii States

O c t o b e r T erm , 1978

No. 78-6140

(A-697)

ALPHONSO MORGAN,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

F r e d e r ic k A. O. S c h w a r z , J r .,

One Chase Manhattan Plaza,

New York, N.Y. 10005

Counsel for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

J o h n H. P ic k e r in g ,

1666 K Street N.W.,

Washington, D.C. 20006

T ho m as J. D o u g h e r t y ,

M a rk P. S c h n a p p ,

C a t h e r in e M. R a y m o n d ,

F r a n c is P. B a r r o n ,

C r a v a t h , S w a in e & M o o r e ,

One Chase Manhattan Plaza,

New York, N.Y. 10005 March 24, 1979.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

O p in io n B e l o w .......................................................................... 1

J u r is d ic t io n .......................................... 2

T h e S ta y in t h is C o u r t .......................................................... 3

C o n s t it u t io n a l a n d St a t u t o r y P r o v isio n s I n

v o l v e d ................................................................................ 3

Q u e st io n s P r e s e n t e d ............................................................. 4

On the Merits....................................................... 4

On the Imposition of the Death Penalty...... ....... 4

On the Denial of Counsel.................. 6

Sta tem en t o f t h e C ase ............... 6

How t h e F ed era l Q u e st io n s W ere R a is e d ............... 16

R easons for G r a n t in g th e W r it .................................... 18

Page

I. P e t it io n e r ’s c o n fe ssio n s w e r e in

a d m issible IN THAT THEY WERE TAINTED

BY HIS UNLAWFUL ARREST AND WERE IN

VOLUNTARY. T h e fa il u r e of t h e t r ia l

COURT TO HOLD A FULL AND FAIR HEARING

ON THE ADMISSIBILITY OF HIS POST-ARREST

STATEMENTS DENIED PETITIONER DUE PRO

CESS OF LAW.................... ........................................ 19

II. The JURY INSTRUCTIONS APPROVED BY

G e o r g ia ’s S u pr em e C o u r t are fla tly

INCONSISTENT WITH THIS COURT’S RECENT

RULINGS AS TO WHEN A DEATH SENTENCE

MAY CONSTITUTIONALLY BE IMPOSED............ 21

A. The Jury Was Not Told Its Decision on

Life or Death Must Include Focus on

the Particular Characteristics of the

Defendant.......................................... 22

B. The Term “Mitigating” Was Not De

fined for the Jury, and Concrete Ex

amples of Mitigating Circumstances

Were Not Provided............................ 23

C. The Jury Also Was Not Informed That

It Should Weigh “Mitigating” Cir

cumstances Against Aggravating Cir

cumstances ......................................... 26

ii

D. The Jury Also Was Not Told It Could

Impose a Life Sentence Even if It

Found One of the Statutory

Aggravating Circumstances. Indeed

the Overall Impact of the Charge

Was To Suggest It Could Not............ 26

E. The Decision Below Is Based Upon

Misunderstanding of This Court’s

View of the Constitutional Require

ments in Death Cases...................... ......... 27

III. T h e d ea th pe n a l t y in s t r u c t io n s also

RAISE THE IMPORTANT AND RECURRING

QUESTION AS TO WHETHER, WHERE THE

STATUTORY SCHEME PROVIDES THAT THE

JURY’S DECISION ON DEATH MUST BE FOL

LOWED BY THE TRIAL JUDGE, THE JURY MAY

NONETHELESS BE LED TO BELIEVE THAT ITS

ROLE IS ONLY TO “ RECOMMEND” OR “ ASK”

FOR DEATH................................................................ 28

IV. C o n tr a r y t o t h is C o u r t ’s e x pe c t a t io n s

AS EXPRESSED IN Gregg, THE GEORGIA

COURTS HAVE NOT NARROWED THE VAGUE

AND OVERBROAD STATUTORY AGGRAVAT

ING CIRCUMSTANCE USED AGAINST PETI

TIONER. T h u s , h is d ea th sen ten c e w a s ,

FOR THAT ADDITIONAL REASON, THE UN

CONSTITUTIONAL RESULT OF UNFETTERED

JURY DISCRETION................................................... 30

V. T h e G e o r g ia Su pr em e C o u r t a lso has

ABANDONED THE APPELLATE REVIEW PRO

CESS WHICH WAS ASSUMED BY THIS COURT

IN Gregg TO BE AN IMPORTANT CON

Page

STITUTIONAL SAFEGUARD.......... ............... 33

VI. F a il u r e t o t r a n sc r ib e th e a r g u m e n t s t o

THE JURY AND TO PROVIDE THEM TO THE

APPELLATE COURT DEPRIVED PETITIONER

OF DUE PROCESS OF LAW..................................... 37

VII. T h e in c o n s is t e n t trea tm en t o f c a p it a l

CASES BY THE GEORGIA COURTS RENDERS

a ll G e o r g ia d ea th sen ten ces u n c o n

s t it u t io n a l ............................................................ 39

VIII. T h e case also sh o u l d be h ea r d so as t o

reiterate the fundamental principal

THAT COUNSEL MAY NOT BE DENIED WHERE

LIFE IS AT STAKE...................................................... 40

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Aguilar v. Texas,

378 U.S. 108 (1964)......................................... 19

Andres v. State,

333 U.S. 740 (1948)......................................... 21

Banks v. State,

237 Ga. 325, 227 S.E.2d 380 (1976), cert,

denied, 430 U.S. 975 ( 1977)......................... 31-32

Berger v. United States,

295 U.S. 78 ( 1935)........................................... 38

Berry hill v. State,

235 Ga. 549, 221 S.E.2d 185 (1975), cert,

denied, 429 U.S. 1054 (1977)....................... 37

Birt v. State,

236 Ga. 815, 225 S.E.2d 248, cert, denied, 429

U.S. 1029 (1976).......................................... 37

Blake v. State,

239 Ga. 292, 236 S.E.2d 637, cert, denied, 434

U.S. 960 (1977)............................................ 36

Bollenbach v. United States,

326 U.S. 607 (1946) ........... ............................. 29

Brown v. Illinois,

422 U.S. 590 (1975)..... ...................... ........... . 19,20

Gallon v. Utah,

130 U.S. 83 (1889)........................................... 21

Coker v. Georgia,

433 U.S. 584 (1977)......................................... 24

Coolidge v. New Hampshire,

403 U.S. 443 (1971) 20

IV

Cases Pjjgg

Dix v. State,

238 Ga. 209, 232 S.E.2d 47 (1977)......... . 36

Dobbert v, Florida,

432 U.S. 282 (1977)...... ......... ....... ..... ..... . 29-30

Douglas v. California,

372 U.S. 353 (1963).......... .............................. 40

Duhart v. State,

237 Ga. 426, 228 S.E.2d 822 (1976)..... . 35, 40

English v. State,

234 Ga. 602, 216 S.E.2d 851 (1975)............ . 35

Fleming v. State,

240 Ga. 142, 240 S.E.2d 37 (1977)................ 29

Floyd v. State,

233 Ga. 280,210 S.E.2d 810 (1974)......... . 37

Frazier v. Cupp,

394 U.S. 731 (1969)....... ................................. 21

Furman v. Georgia,

401 U.S. 238 (1972)....... ......................... ....... 17,18,28,

37, 39

Gardner v. Florida,

430 U.S. 349 (1977)........................... ......... . 37, 39

Gibson v. State,

236 Ga. 874, 226 S.E.2d 63 (1976).... ............. 37

Gillespie v. State,

236 Ga. 845, 225 S.E.2d 296 (1976)................ 35

Groyned v. City of Rockford,

408 U.S. 104 (1972)................ ................... . 33

Gregg v. Georgia,

428 U.S. 153 (1976)........................................ . Passim

Griffin v. California,

380 U.S. 609 (1965)........................................ 38

V

Cases Page

Haley v. Ohio,

332 U.S, 596 (1948)......................................... 21

Harris v. State,

237 Ga. 718, 230 S.E.2d i (1976), cert, de

nied, 431 U.S. 933 ( 1977)............................. 32,36

Hawes v. State,

240 Ga. 327, 240 S.E.2d 833 ( 1977)...... . 29, 38

Heflin v. United States,

358 U.S. 415 ( 3959)......................................... 2

House v. State,

232 Ga. 340, 205 S.E.2d 217, cert, denied, 428

U.S. 910 (3974).............. ............................. 36,37

Jackson v. Denno,

378 U.S. 368 (1964)......................................... 20

Jarrell v. State,

234 Ga. 410, 216 S.E.2d 258 ( 1975), cert.

denied, 428 U.S. 910 (1976)......................... 37

Jurek v. Texas,

428 U.S. 262 (1976)......................................... 22,26,27

Lego v. Twomey,

404 U.S. 477 (1972).............. ............. ........... . 20

Lisenba v. California,

314U.S. 219 (1941)......................................... 23

Lockett v. Ohio,

- U.S. _ , No. 74-329, slip op. (July 3, 1978). 23,29

Mason v. State,

236 Ga. 46, 222 S.E.2d 339 (1975), cert.

denied, 428 U.S. 910 (1976)......................... 13,28

Mayer v. City o f Chicago,

404 U.S. 189 ( 1971)................ ........................ 39

McCorquodale v. Georgia,

233 Ga. 369, 211 S.E.2d 577 (1974), cert.

denied, 428 U.S. 910 (1976)......................... 31, 36, 37

VI

Cases Pggg

MeGautha v. California,

402 U.S. 183 (1971)...................................... . 22

McKenna v. Ellis,

280 F.2d 592 (5th Cir. 1960) ................. ......... 41

Payton (Riddick) v. New York,

No. 78-5420 (Oct. Term 1978)..... .............. 20

Perez v. United States,

297 F.2d 12 (5th Cir. 1961)..................... ........... 29

Pollard v. United States,

352 U.S. 354 (1957)................... .......... .......... 18

Powell v. Alabama,

287 U.S. 45 (1932)........................................... 19,40

Prevatte v. State,

233 Ga. 929, 214 S.E.2d 365 (1975)................ 29, 38

Proffitt v. Florida,

428 U.S. 242 (1976) ......................................... 22, 26, 28, 29

Roberts v. Louisiana,

428 U.S. 325 (1976)........... ........... ................. 23

Sanchez v. State,

236 Ga. 848, 225 S.E.2d 296 (1976)................. 35

Sanders v. State,

235 Ga. 425, 219 S.E.2d 292 (1976)........ ..... 25,35

Schacht v. United States,

398 U.S. 58 (1970)............ ................. .......... 2

Schmidt v. Hewitt,

573 F.2d 794 (3d. Cir. 1978).......... ............. . 21

Silber v. United States,

370 U.S. 717 (1962)........................................ 18

Smith v. United States,

230 F.2d 935 (6th Cir. 1977)................ ........ 29

Spano v. New York,

306 U.S. 315 (1959)......................................... 21

Spinelli v. United States,

393 U.S. 410 (1969)......................................... 19

Spinkellink v. Wainwright,

No. 78-6048 (filed Jan. 16, 1979).................... 6

Spivey v. Georgia,

vii

Cases Page

241 Ga. 477, 246 S.E. 288 (1978), cert, de

nied, No. 78-5460, slip. op. (Dec. 4, 1978)... 17, 19, 27,

28, 39

Stanley v. State,

240 Ga. 341,241 S.E.2d 273 (1977)................ 37

Stephens v. Hopper,

241 Ga. 596, 247 S.E.2d 92 (1978), cert,

denied, — U.S. —, No 78-5544, slip. op.

(Nov. 27, 1978)............................................ 38,39

Stovall v. State,

236 Ga. 840, 225 S.E.2d 292 (1976).............. 25, 35

Taglianetti v. United States,

394 U.S. 316 (1969).... .................................... 2

Taylor v. Kentucky,

436 U.S. 478 (1978)........... ............................. 21

Thomas v. State,

240 Ga. 393, 242 S.E.2d 1 (1977), cert. de-

nied, 436 U.S. 914 (1978)............................. 36,37

United States v. Atkinson,

297 U.S. 157 (1936).......... ............................... 18

United States v. Pope,

561 F.2d 663 ( 6th Cir. 1977)................... ....... 29

United States v. Woods,

487 F.2d 1218 (5th Cir. 1973)......................... 41

Vachon v. New Hampshire,

414 U.S. 478 (1974) . 18

VU1

Coses Page

Wong Sun v. United States,

371 U.S. 471 (1963)......................................... 19,20

Woodson v. North Carolina,

428 U.S. 280 (1976) ............................. ............ 18, 19, 22, 23

Young v. State,

239 Ga. 53, 236 S.E.2d 1, cert, denied, 434

U.S. 1002 (1977)........ ................................. 37

Other Authorities

Cardqzo, Law and Literature (1931).......... ........... 22

Stern and Gressman, Supreme Court Practice, 5th

ed-1978)...... ....................................... ........... . 2,17

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3)..... ........................................... 2

28 U.S.C. § 2101(d)............................................... . 2

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2503(b)................................... 27

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2514......................................... 13,28

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534.1 ......................... ........... . 24

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534.1 (b )(7 ).......................... 31

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534.1(c) ................. .............. 26

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2537(a)................................... 7, 15

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2537(e)................................ . 34

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2537(c)(3)............................. 34

Rules and Regulations

Rule 34 of the Supreme Court of Georgia............... 59a

IN THE

(&smtt % In M

October Term, 1978

No, 78-6140

(A-697)

ALPHONSO MORGAN,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Petitioner Alphonso Morgan respectfully prays that a

Writ of Certiorari issue to review the judgment of the

Supreme Court of Georgia affirming his conviction for

murder, kidnapping and armed robbery, and—by a 4-3

vote—affirming his sentence of death for murder.

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia affirm

ing Petitioner’s conviction and sentence, and the opinion

dissenting from the imposition of the death penalty, are

reported at 241 Ga. 485, 246 S.E.2d 198 (1978), and

printed in Appendix E at 11a.*

* References to the Appendices are designated by the suffix “a”.

2

JURISDICTION

This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked under 28 U.S.C

§ 1257(3).

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia was

entered on June 28, 1978.

The untimeliness of the petition is not jurisdictional,

at least in criminal cases of this sort, where the statute (28

U.S.C. § 2101(d)) authorizes this Court to fix the time by

rule.1

This Court should here exercise its discretion to waive

the normal time limits: first, because death is unique and

irreversible;2 second, because of the seriousness of the

constitutional errors involved—including the complete

failure by the Georgia courts to fulfill the expectations that

a plurality of this Court relied upon in concluding in 1976

that the Georgia death penalty statute could be adminis

tered constitutionally; and, third, because of the abandon

ment of petitioner, an incarcerated indigent black youth,

by his Georgia assigned counsel both before and after the

decision of the State Supreme Court.3

1 See Schacht v. United States, 398 U.S. 58, 63-64 ( 1970)

Taglianetti v. United States, 394 U.S. 316 (1969); Heflin v. United

States, 358 U.S. 415, 418 n.7 (1959); see also Stern and G ressman,

Supreme Court Practice, 389-95 (5th ed. 1978), listing numerous

examples of late filings permitted by this Court, including cases from

state courts where Rule 22(1) would be applicable.

2 See Stern and G ressman, op. cit, at 391(d) and 393(k).

3 Following the decision of the Georgia Supreme Court, assigned

counsel did absolutely nothing but tell petitioner (by telephone) that

he had been “turned down.” See Motion for Stay of Execution at 2.

He did not even advise petitioner of his possible remaining remedies.

Petitioner made numerous unsuccessful attempts to obtain counsel

and advice as to his legal options (App. at 42a, 53a, 54a, 64a.) It was

only on January 30, 1979—with his electrocution scheduled for

February 7—that petitioner finally was able to secure legal assistance.

Motion for Stay of Execution at 2; App. at 3a.

3

THE STAY IN THIS COURT

On or about January 30, 1979, petitioner was notified

that he would be electrocuted on February 7, 1979 (App.

at 3a).

Millard Farmer thereupon agreed to represent peti

tioner in order to seek a stay of execution from this Court

and to obtain other counsel to represent him in petitioning

this Court. An application for a stay was filed on

February 1, 1979, accompanied by a hurried certiorari

petition, required to obtain the stay. That petition in

dicated that within 30 days new pro bono counsel would

convert the “overnight petition” into a “meaningful legal

document”. Petition at 8; see Motion for Stay of Execu

tion at 2.

On February 2, 1979, Mr. Justice Powell stayed

execution of the death sentence pending disposition of

petitioner’s writ of certiorari (App. at 6a).

On February 24, 1979, the Clerk of this Court advised

the undersigned by letter (App. at 10a) that petitioner

would have until March 24, 1979, to supplement the

petition.4 Undersigned counsel concluded that this self-

contained petition would best serve the interests of peti

tioner and the interests of justice, and thus the previously

filed “overnight petition” need only be referenced as

background.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The relevant provisions of the United States Con

stitution and the Georgia statutes are printed in Appendix

V at 88a.

4 The undersigned meanwhile had been requested by petitioner

(initially through the NAACP Legal Defense Fund) to represent him

in these proceedings.

4

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

On the Merits

1. Whether petitioner’s confessions should have been

excluded:

(a) as the fruit of an unlawful arrest where (i)

there was only conclusory testimony that information

supporting probable cause was reliable, (ii) no war

rant was obtained for the daybreak arrest in petition

er’s home (although the police conceded facts which

demonstrated time to secure a warrant), and (iii) the

trial court declined to rule on the legality of the arrest;

and

(b) as involuntary where the trial court ruled the

confession admissible after a “hearing” (i) in which

it excluded testimony suggesting that petitioner did

not realize that his oral statements could be used

against him; (ii) which it cut off before the circum

stances of the confession (including police deception)

had been revealed; and (iii) in which it failed to

consider petitioner’s youth and education and his

interrogation by at least four police officers at day

break?

On the Imposition of the Death Penalty

In Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S, 153 (1976), this Court

upheld the facial constitutionality of the Georgia capital

sentencing scheme based on assumptions that the jury’s

discretion could and would be guided by the trial court’s

instructions, and that mandatory appellate review could

and would prevent arbitrariness and caprice. This case

raises the important constitutional issue whether the

Georgia scheme, as actually administered, meets the

requirements of the United States Constitution. More

specifically, this petition raises the questions:

5

2. Whether the death penalty may be constitutionally

imposed on the basis of jury instructions that: (a) fail to

instruct the jury to focus on the characteristics of the

defendant as well as the nature of the crime, (b) fail to

explain the term “mitigating”, or to direct the jury’s

attention to specific mitigating circumstances present in

the case, while expressly commenting on particular

aggravating circumstances, (c) do not guide the jury to

weigh mitigating circumstances against aggravating cir

cumstances, and (d) do not inform the jury that even if it

finds a statutory aggravating circumstance it may nonethe

less decide in favor of a life sentence?

3. Whether, where the trial judge must follow a jury

death verdict, it is constitutional for the court to suggest to

the jury that its function is only to “ask” for or “recom

mend” death or life?

4. Whether the statutory “aggravating circumstance”

upon which the jury relied in deciding upon death is so

overbroad and vague that petitioner’s sentence based

upon this statutory provision was unconstitutional?

5. Whether the Georgia Supreme Court has failed to

follow the appellate review process which this Court

assumed in Gregg to be necessary to the constitutionality

of the Georgia statutory scheme?

6. Whether failure to transcribe the prosecutor’s

summations to the jury in a death case deprives a defend

ant of due process because it necessarily means the record

made available cannot disclose all the considerations

which motivated the jurors to impose the death sentence?

7. Whether the inconsistent treatment of death

penalty cases by the Georgia courts has so enhanced the

risk of arbitrary and capricious imposition of the death

6

penalty that such imposition is now unconstitutional in any

case?5

On the Denial of Counsel

8. Whether, in a capital case, there has been an

unconstitutional denial of counsel when (a) Georgia

appointed as counsel a lawyer who had less than two years

of experience, not in the criminal field, to represent an

indigent black youth who had not finished high school, in

a highly publicized murder case which was to be tried

before a jury; (b) both the trial and the appellate court

were aware that defendant sought new assigned counsel,

and assigned trial counsel had told the trial court that

because of the lack of cooperation by his client he was

unable to put on a defense through the client; and (c) on

the mandatory review of defendant’s death sentence,

assigned trial counsel failed even to appear at oral argu

ment, and the court subsequently asked the state—but not

the defendant—to brief the issue of the death penalty

instructions?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The charge for which petitioner was arrested, tried,

convicted and sentenced to death was that he acted in

concert with Jose High and Judson Ruffin to murder

James Gray on August 22, 1976.6 Petitioner was tried

alone.

5 By reference to Petition for Writ of Certiorari at 43-45, 47 n. 46

and Appendix F, Spinkellink v. Wainwright, No. 78-6048 (filed Jan.

16, 1979), petitioner also raises the question whether in light of the

growing body of data indicating that racial factors play a role in death

sentencing the death penalty can be constitutionally imposed in

Georgia?

6 The indictment is Appendix G at 35a.

7

Petitioner. Petitioner is a black youth; he was 17 or

18 in August 1976. He had not completed high school.

He had no prior criminal record.7

Petitioner’s Assigned Counsel. Assigned counsel had

less than two years experience, and did not specialize in

criminal law. During trial, he announced that “lack of

cooperation” precluded submitting a defense through

petitioner (Tr. 193). After his client was convicted and

sentenced to death, assigned counsel took no interest in

the case. Petitioner himself filed a notice of appeal.

Assigned counsel had to be ordered to file a brief by the

Georgia Supreme Court. He did not even attend oral

argument. After the Georgia Supreme Court decision,

assigned counsel did nothing to help petitioner.8

Dates of Arrest and Trial. Petitioner was arrested

without a warrant, charged with Gray’s murder, and taken

7 Race appeared from observation and from numerous references

to black persons in the trial transcript. The arresting officer testified

that petitioner said his age was 17 (Tr. 115); the trial judge’s Report,

submitted in the form of a questionnaire (see Ga. Code Ann.

§2537(a)) to the Georgia Supreme Court (App. at 67a) said he was

bom on “ 1/1/58”, which would have made him 18. Education is

shown by Tr. 115 and the Report (App. at 67a). Lack of prior record

is shown by the Report (App. at 71a).

References to “Tr.” are to the transcript of petitioner’s trial, a

copy of which is being filed with the Clerk of this Court.

8 In his Report, the judge checked a box indicating that ap

pointed counsel had less than five years experience, and that the

nature of his practice was “general” (App. at 71a). The Georgia

State Bar records show he had been admitted for less than two years

as of August, 1976. Counsel’s lack of interest in petitioner’s case is

shown by petitioner’s pro se notice of appeal, petitioner’s letters to the

authorities seeking counsel, and by the letter from the Georgia

Supreme Court ordering him to file a brief or face sanctions (App. at

59a). The Clerk of the Georgia Supreme Court reported by telephone

on March 20, 1979, that counsel did not appear for oral argument.

The records of the Georgia Supreme Court show that assigned

counsel—unlike the State—was not asked to submit a brief on the

crucial issue of the death penalty instructions.

8

into custody on August 28, 1976. His trial did not take

place until July 1977.9

The Trial: Jury Selection. Every potential juror was

examined about the death penalty, first by the court as a

group, and then individually (in each other’s presence) by

counsel (Tr. 3-68).10 Twenty-one of the thirty examined

were also asked by the prosecutor if they would agree to

“recommend” or “impose” death in cases of murder with

“aggravating” circumstances.

Aggravated murder, though undefined, thus became

a familiar term to the panel. The term “mitigating” was

not mentioned during voir dire.

On 18 separate occasions during voir dire, it was

indicated that the crime (in the first instance) and the trial

(contemporaneously) were the subject of extensive pub

licity.

The Trial: Evidence Relating to Whether or Not

Morgan Was Guilty. It was undisputed that Gray had

been shot at close range and that earlier he had been

driving in an area where three unidentified blacks had

been seen drinking.

The only evidence implicating petitioner, however,

were confessions.

9 At his trial, petitioner contended that the State, after first

indicting him in 1976, had reindicted him in the May 1977 grand jury

term in order to circumvent his right to a speedy trial. The

prosecutor’s only response was to confirm that the trial was in fact on

the later indictment. The court, without addressing the merits, then

simply asked the prosecutor to swear in the jury and proceeded with

the trial (Tr. 70-71).

10 The prosecutor struck all jurors who said they were opposed to

the death penalty (Tr. 5, 57). The prosecutor also struck (i) a juror

who was “undecided” about the death penalty (Tr. 35), (ii) a juror

who believed in the death penalty only in “some cases” (Tr. 31-32),

(iii) a juror who, when asked if he was strongly in favor, lukewarm,

or undecided about the death penalty, said “I would have to hear the

evidence” (Tr. 46), and (iv) two jurors who had some doubt about

whether they could impose the death penalty (Tr. 17, 59).

9

J. B, Dykes, County Sheriff’s investigator, testified

that he, the Sheriff, a third named officer, and “a number

of other officers” arrested Morgan in his home at “day

break” on August 28, 1976 (Tr. 108).

At this point, a hearing was held outside the presence

of the jury (Tr. 108-23). Morgan challenged the legality

of his warrantless arrest and the voluntariness of the

confession that ensued. At the hearing, the substance of

the police testimony was as follows:

Dykes testified that Jose High had been arrested

when it was “just getting dark” on August 27, and at

about 3:30 or 4:00 the next morning had confessed

“numerous crimes”, implicating petitioner in the Gray

murder and other crimes (Tr. 111-12).11

The police proceeded to arrest Morgan in his home

“immediately” after 3:30 or 4:00, or at “daybreak”. They

did not have, or seek, an arrest warrant (Tr. 119-20).

Dykes said they feared Morgan would be gone when he

found out High had been arrested (Tr. 112). But the

police had the area “completely surrounded” (Tr. 119).

Dykes testified that Miranda warnings were read to

Morgan in his house and in a car going down to the police

station. Morgan said he knew nothing about the charges

(Tr. 115.)

By approximately 7:00 a.m., Morgan was in the

county jail. Dykes, plus the Sheriff and two other named

police officers, and with “other officers present”, began to

interrogate Morgan some more, without, said Dykes,

11 Dykes said the police concluded that the information in High’s

confession was “very reliable” (Tr. 112). He did not explain this

answer, but presumably it referred to evidence involving High

himself, as opposed to Morgan, because the State never introduced

any evidence linking Morgan to the crime other than his own

confession. Dykes also said that, at a lineup which included High,

some unidentified person gave a name of “something like Alonzo”

(Tr. 117).

10

using any threats or promises. (Tr. 116-17.) A con

fession apparently ensued—but there was no testimony

during the hearing as to the circumstances immediately

preceding Morgan’s confession in the county jail. Each

time Dykes attempted to transcribe the statements, Mor

gan would stop talking (Tr. 121).

At the conclusion of the hearing, the court ruled that

a confession had been “prima facie” voluntarily made.

The court declined to rule on whether the arrest had been

illegal, thereby infecting the ensuing confession—stating

that it was “not essential to my ruling on the question of

the confession at this time”. (Tr. 122-23.)

The circumstances of the actual confession were

described to the jury. Dykes said he again read Morgan

his Miranda rights in the jail (Tr. 127). Morgan contin

ued his denials. Then Dykes for the first time testified that

he had deceived Morgan by telling him that his finger

prints were on a gun placed on the table before him, and

that he had a photograph of Morgan’s footprint at the

crime scene. Dykes testified that Morgan then said, “All

right, I was there. Jose made me shoot him. He’s the only

one I killed”. (Tr. 128.)

Dykes—who conceded that he had no writing re

garding the confession, and indeed that Morgan would

“just quit talking” whenever he tried to take notes or tape

record (Tr. 121, 133)—testified that petitioner had further

admitted that High, Ruffin and he had abducted the

victim from his truck, placed him in the trunk of Ruffin’s

car, and took him to an airfield. There High blindfolded

the victim, and Ruffin and petitioner shot him. (Tr. 131-

32.)

Dykes later testified that the next day he and two

fellow officers again interrogated petitioner. According to

Dykes, when asked the reason for the murder, petitioner

responded “because he’s white”. (Tr. 143.)

11

Only one witness was called by petitioner’s assigned

counsel—an agent of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation,

originally scheduled to testify for the State (Tr. 196). The

agent testified that on August 29 he had taken written

notes of a statement made by Morgan, which Morgan had

signed.12 Morgan had said that he was under threat of his

life when he shot the victim:

“Jose said to shoot him. I said I’m going to

shoot—I said I’m not going to shoot. ‘If you don’t

shoot him, kneel down and I’ll shoot you and the man

both.’ Jose put the hand on my face, turned my head,

and then I fired shotgun. He didn’t die. I shot him in

the shoulder. The Cowboy [Ruffin] shot him with

double barrel shotgun one time. I saw the man’s

head bust open. I cried and went back to the car.

Jose said, ‘Don’t cry like a baby. You’re a grown

man now. You’re part of the family. If you tell the

police, I’ll kill you and your family.’ Jose had man’s

wallet in his hand, then we left in the Roadrunner

and stopped at Church’s Chicken on Gwinnett Street

and talked. Jose laughed, then they took me home.”

And it was signed, ‘Alphonso Morgan’.” (Tr. 202-

203.)

The agent testified that Ruffin, in a separate con

fession, stated that both he and petitioner shot Gray (Tr.

204). High had told the agent in his confession that he

was the leader of a “family” whose object was to “kill and

rob and rape people” (Tr. 200). High, however, denied

forcing either petitioner or Ruffin to shoot Gray (Tr. 204).

During the interrogation by the agent, High showed no

remorse for his participation in the Gray murder or other

murders (Tr. 209).

12 The agent said Dykes had told him he had talked with Morgan

but that he had not related any statement by Morgan (Tr. 198-99).

12

Charge13 and Conviction. The court instructed the

jury that coercion (a reasonable belief that an act was

necessary to prevent imminent death or great bodily

injury) would be a defense to any crime, except murder.

The jury’s verdict said we “find” defendant guilty as

charged (App. at 29a).

The Punishment Phase. Neither side introduced any

additional evidence.

Counsel for both sides argued to the jury, but their

arguments were not transcribed.

The court’s charge on punishment (App. at 30-32a)

was primarily devoted to discussion of “aggravating cir

cumstances”. The court told the jury there were three

possible statutory aggravating circumstances:

(i) the offense was “outrageously or wantonly

vile, horrible, or inhuman in that it involved torture,

or depravity of mind, or an aggravated battery to the

victim”;

(ii) the offense was committed in the course of

another capital felony, armed robbery; and

(iii) the offense was committed for the purpose

of receiving money (App. at 31a).

The trial judge did not define any of the broad terms

in the first above-quoted circumstance except for “aggra

vated battery”, which was defined so broadly that the act

of murder itself would constitute an “aggravated battery”

(A/.)-14

After an extensive treatment of aggravating circum

stances, the trial judge did not tell the jurors either (i) that

13 The charge on the merits is printed at App. at 20a.

14 The definition was: “maliciously causes bodily harm to anoth

er by depriving him of a member of his body, or by rendering a

member of his body useless, or by seriously disfiguring him, his body,

or a member thereof’ (App. at 31a).

13

they should weigh “mitigating” against aggravating cir

cumstances, or (ii) that even if they found a statutory

aggravating circumstance they could nonetheless vote for

life imprisonment,

The trial judge also did not tell the jurors that in

voting for death or life they must focus upon the defend

ant himself, as well as on the crime. The trial judge did

not tell the jurors that they could consider the defendant’s

age, his claim of mortal duress (which they had just been

told was irrelevant to the issue of guilt for murder), or his

lack of prior criminal record. The court did not explain

the term “mitigating”. The only mention of the legal term

“mitigating” was in the midst of a sentence at the end of

the first paragraph of the charge which told the jury “You

should consider all of the facts and circumstances of the

case, including any mitigating or aggravating circum

stances” (App. at 30a).

The court’s final instruction to the jury on their role

was:

“You must designate in writing in your verdict

on the indictment the aggravating circumstance or

circumstances which you find to have existed with

respect to the offense for which you recommend the

death penalty.” (App. at 32a, emphasis supplied.)

Although the judge had earlier stated (as is correct

under Georgia law)15 that he would be required to follow

a jury death verdict, he also had stated that if the jury

favored death, the form of its verdict should be to

“recommend” it (App. at 32a).

The jury returned with the written statement:

“We ask the death penalty for the offense of

murder was outrageously and wantonly vile, horrible,

15 Ga. Code Ann. §27-2514; see Mason v. State, 236 Ga. 46, 222

S.E.2d 339, 342, ( 1975), cert, denied, 428 U.S. 910 ( 1976).

14

or inhuman in that it involved torture, depravity of

mind and aggravated battery to the victim. May God

rest his soul.” (App. at 33, 35a, emphasis supplied.)

The trial judge thereupon ordered petitioner’s elec

trocution to take place on August 17, 1977 (App. at 34a).

From start to finish—jury selection, opening state

ment of the prosecution,16 testimony of 13 witnesses,

“hearing” on the confession, argument, instructions, jury

deliberation and verdict, further argument and instruc

tions on punishment, further jury deliberation, the death

verdict, and the sentence of electrocution— petitioner’s

trial took two days.

Petitioner’s Appeal. On July 19, 1977, petitioner

himself filed a handwritten notice of appeal. This was

coupled with a request that counsel be appointed to

represent him on his appeal. (App. at 40a.)

The request was ignored.

Shortly before December 19, 1977, petitioner wrote a

three-page handwritten letter to the Georgia Supreme

Court stating that he was innocent, that at trial his

appointed lawyer “gave me no cooperation”, and that his

appointed lawyer had given him no report about his case

(App. at 54a).

Still continuing to ignore petitioner’s request for

appellate counsel, and his complaints about trial counsel,

the Georgia Supreme Court ordered petitioner’s pre

viously assigned trial counsel to file a brief. That

brief—only 11 pages—was filed on December 29, 1977.

Oral argument was held on January 9, 1978. Mor

gan’s previously assigned trial counsel did not even ap

pear, and so no argument was made on Morgan’s behalf.

16 Counsel for petitioner did not make an opening statement at

any stage of the proceedings.

15

At the oral argument, the court asked the State to file

a supplemental brief addressing the adequacy of the trial

court’s sentencing charge, and, in particular, its treatment

of mitigating and aggravating circumstances. Neither

Morgan nor his counsel was asked to file a brief on that

crucial issue (on which the Georgia Supreme Court later

divided 4-3).

The record made available to the Georgia Supreme

Court did not include the prosecutor’s arguments in favor

of the death penalty, which had not been transcribed.

By statute, the trial judge in death cases is supposed

to prepare answers to a questionnaire about the defend

ant, the offense, and the circumstances of the trial, and to

send it to the Georgia Supreme Court with the record. Ga.

Code Ann. §27-2537(a). The record went to the State

Supreme Court on October 17, 1977. But the question

naire was not filled out by the trial judge until March 27,

1978—about half a year later, and almost three months

after the oral “argument”.

The questionnaire (App. at 67a) (i) contains clearly

inaccurate statements, (ii) is internally inconsistent and

(iii) on its face, reveals deficiencies in the trial judge’s

death penalty charge. Thus,

(i) the trial judge told the Georgia Supreme

Court there was no evidence of “mitigating circum

stances”—even though the questionnaire form itself

specifies as possible mitigating circumstances

“youth”, “duress”, and lack of prior criminal activity;

(App. at 69-70a)17

17 The record plainly showed defendant’s youth and his con

tention of duress, and did not show any history of prior criminal

activity. In other parts of the questionnaire, the trial judge himself

reported that defendant had no record of prior convictions, that he

had been bom “ 1/1/58”, that he had not finished high school (also

shown at Tr. 115), and that he had only a “medium” (“IQ 70-100” )

intelligence level (App. at 67a).

16

(ii) the trial judge said race was not an

issue—even though the prosecutor had ended his

direct examination of investigator Dykes after the

“because he’s white” statement referenced above

(App. at 72a);

(iii) the trial judge conceded that there had been

“extensive publicity” about the case, but said the jury

had not been instructed to disregard the publicity

(id.),

(iv) the trial judge also conceded that the jury

had not been instructed to “avoid any influence of

passion, prejudice or any other arbitrary factor when

imposing sentence” (stating at the same time his view

that there was “no evidence” that the jury had been

so influenced) (id.).

On June 28, 1978, the Georgia Supreme Court issued

its opinion. The official reporter shows petitioner as

having represented himself pro se, in addition to the

appointed trial counsel who had abandoned him (App. at

11a).

The decision was unanimous on the merits, but

divided 4-3 on the death sentence.

The one-vote majority, without any explanation

whatsoever, said it found “no error” in the sentencing

charge, and went on to approve the sentence of death

(App. at 14a).

HOW THE FEDERAL QUESTIONS WERE RAISED

Understandably, because of the lack of counsel at

critical stages, the Federal questions involved were not

raised and pressed with the precision that is desirable.

Nevertheless, they were sufficiently raised and considered

by the Supreme Court of Georgia to sustain this Court’s

17

jurisdiction, particularly given the circumstances and the

fact that petitioner’s life is at stake.

1. The illegality of the arrest and the ensuing

confession were raised in the trial court and on appeal,

and were explicitly decided by the Georgia Supreme

Court on Federal constitutional grounds, citing decisions

of this Court.

2. The propriety of the death penalty instructions was

focused upon in the Georgia Supreme Court as part of its

mandatory death sentence review. While the opinion does

not explicitly state that the point was resolved on Federal

grounds, that is necessarily so (i) given the court’s reliance

on Spivey v. Georgia, 241 Ga. 477, 246 S.E.2d 288 ( 1978),

cert, denied, No. 78-5544, slip. op. (Nov. 27, 1978),

decided 20 days previously, which explicitly purported to

decide the death penalty instructions issue based upon this

Court’s views on the United States Constitution, (p. 27,

infra), and (ii) in light of Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153

(1976), and Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972),

which make the adequacy of the procedures used to

sentence a defendant to death matters of Federal con

stitutional law.

The language of the opinion sufficiently indicates that

these federal questions were considered and disposed of.18

Petitioner should not be prejudiced because the Georgia

Court chose to be cryptic—particularly since its standard

less review of death cases in general itself raises a serious

and substantial federal constitutional issue.

3. Petitioner’s contention that he was uncon

stitutionally denied counsel was raised in the Court below

by petitioner himself, albeit without legal sophistication

(App. at 54a). The issue was obvious to the Georgia

Supreme Court. Indeed, that court declined even to ask

18 See Stern and G ressman at 220 and cases there discussed.

18

petitioner or his counsel to submit papers on what that

court itself perceived as a crucial issue—the death penalty

instructions.

Jurisdiction to review each of the foregoing matters

and the others raised by petitioner is also supported by (i)

the abandonment of petitioner by counsel throughout the

Georgia proceedings, see Pollard v. United States, 352

U.S. 354, 359 (1957); (ii) the unique and irreversible

nature of the death penalty; (iii) this court’s power to

notice “plain error” even though the argument was not

“made in constitutional form” to the state supreme court,

see, e.g., Vachon v. New Hampshire, 414 U.S. 478, 481

(1974); and (iv)

“. . . In exceptional circumstances, especially in

criminal cases, appellate courts, in the public interest,

may, of their own motion, notice errors to which no

exception has been taken, if the errors are obvious, or

if they otherwise seriously affect the fairness, integrity

or public reputation of judicial proceedings”. Silber v.

United States, 370 U.S. 717, 718 (1962) (quoting

United States v. Atkinson, 297 U.S. 157, 160 (1936)).

' REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

In 1972, this Court held that death penalty statutes,

as then administered, were unconstitutional. Furman v.

Georgia, 408 U.S. 238. In 1976, this Court ruled that,

while some new death penalty statutes were uncon

stitutional, e.g., Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280,

others, including Georgia’s, appeared on their face to

contain sufficient safeguards, so that they could be applied

constitutionally, e.g., Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153.

Now the question arises as to how the Georgia

scheme is actually being administered—not at all the way

this Court assumed in Gregg. Thus, petitioner—at peril

for his life—asks this Court to carry forward what it

19

began, to the necessary next step—i.e., this Court should

require that the safeguards which it has held can make the

death penalty constitutional be rigorously observed and

applied. It should hear the case to grant this particular

petitioner his constitutional rights before imposition of the

“unique and irretrievable” penalty of death. Woodson,

428 U.S. at 281. It should also resolve these issues now

because the Georgia Supreme Court—itself closely di

vided on the constitutional questions raised herein—now

faces a “tide” of death penalty cases.19

This petition also raises a classic constitutional con

frontation on the legality of a warrantless arrest and on

the process required to determine the voluntariness of a

confession.

Finally, thirty-seven years after Powell v. Alabama, it

is—amazingly—once again necessary to hear a capital

case in which counsel has been just plain denied.

I. PETITIONER’S CONFESSIONS WERE INADMISSIBLE

IN THAT THEY WERE TAINTED BY HIS UNLAWFUL AR

REST AND WERE INVOLUNTARY. THE FAILURE OF THE

TRIAL COURT TO HOLD A FULL AND FAIR HEARING ON

THE ADMISSIBILITY OF HIS POST-ARREST STATEMENTS

DENIED PETITIONER DUE PROCESS OF LAW.

Petitioner’s confessions were the fruit of a warrantless

arrest without probable cause and should have been

suppressed. Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590, 604-605

(1975); Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471, 484

(1963).

First, the bare conclusory statement that High’s

information was reliable was insufficient to establish

probable cause. Spinelli v. United States, 393 U.S.

410, 416 (1969); Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U.S. 108, 114

19 See the dissent in Spivey v. Georgia, 241 Ga. 477, 246 S.E.2d

288, 293, cert, denied,------ U.S. _____, No. 78-5544, slip op. (Nov.

27, 1978), discussed infra at p. 27.

20

(1964). Moreover, High’s information was not

shown to be the fruit of a lawful arrest. Wong Sun v.

United States, 371 U.S. at 488.

Second, the arresting officer conceded the ab

sence of the one claimed exigent circumstance for the

warrantless arrest—fear that petitioner might flee his

home after discovery of High’s arrest.20 As Officer

Dykes testified, the police had petitioner’s house

surrounded,, thereby providing sufficient time to test

their right to arrest before a neutral magistrate. See

Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443 (1971).

Third, the trial court erroneously failed to rule on

the legality of the arrest. The mere finding that a

confession after Miranda warnings was voluntary,

cannot dissipate the taint of a prior unlawful arrest.

Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. at 604.

Petitioner contends that in any event his confession

was involuntary and that he was denied his right to the

full and fair hearing which would have shown it to be

involuntary. Lego v, Twomey, 404 U.S. 477 (1972);

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964).

First, the court improperly excluded crucial testi

mony as to voluntariness suggesting that petitioner

did not understand that his oral statements could be

used against him. The court precluded cross-

examination as to the reason petitioner refrained

from making further statements each time Officer

Dykes attempted to transcribe the confession. (Tr

121. )

Second, the court cut short the hearing before the

circumstances surrounding the confessions were even

discussed. The fact that the police had deceived

20 The constitutionality of a warrantless arrest in the home absent

exigent circumstances is before the Court in Payton (Riddick) v. New

York, No. 78-5420 (October Term, 1978). Petitioner adopts the

arguments made therein.

21

petitioner by stating that his fingerprints were on the

murder weapon and that his footprints were found at

the crime scene was not revealed until after the

confession had been ruled inadmissable (Tr. 122-

128). Although not controlling, deception is a rele

vant factor that must be considered in a voluntariness

determination. See Frazier v. Cupp, 394 U.S. 731,

739 (1969); Schmidt v. Hewitt, 573 F.2d 794 (3d Cir.

1978). See also Lisenba v. California, 314 U.S. 219,

237 (1941).

Third, in holding the confession voluntary on the

basis of the truncated hearing, the court improperly

took no account of petitioner’s youth and intelligence,

e.g., Haley v. Ohio, 332 U.S. 596, 600-601 (1948), or

the daybreak interrogation by a group of police

officers, e.g., Spano v. New York, 360 U.S. 315

(1959).

II. THE JURY INSTRUCTIONS APPROVED BY

GEORGIA’S SUPREME COURT ARE FLATLY INCONSISTENT

WITH THIS COURT’S RECENT RULINGS AS TO WHEN A

DEATH SENTENCE MAY CONSTITUTIONALLY BE IM

POSED.

It is “quite simply a hallmark of our legal system that

juries be carefully and adequately guided in their deliber

ations.” Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 193 (1976). “In

death cases”, moreover, as this Court recognized long

before its wider rulings in Furman, doubts about the

clarity of instructions should be “resolved in favor of the

accused”. Andres v. United States, 333 U.S. 740, 752

(1948). See also Calton v. Utah, 130 U.S. 83, 87 (1889)

(“fundamental” in cases involving death that instructions

be clear and explicit).

Although criminal defendants are entitled to instruc

tions clear to laypersons as well as legal scholars, Taylor v.

Kentucky, 436 U.S. 478, 484 (1978), it is particularly true

in death cases that instructions should be (as Mr. Justice

22

Frankfurter put it) in clear “simple, colloquial English”,

and (as then Chief Judge Cardozo wrote) given “directly

and not in a mystifying cloud of words”.21

The instructions below do not pass those general

tests. More specifically, they depart in four separate but

reinforcing respects from the very elements of the Georgia

statutory scheme which this Court in Gregg held saved

that scheme from constitutional attack.

A. The Jury Was Not Told Its Decision on Life or

Death Must Include Focus on the Particular Character

istics o f the Defendant,

The instructions leading to the death verdict against

petitioner say not one word about the need to weigh the

defendant’s particular characteristics, as well as the spe

cific circumstances of the crime. Thus, they conflict with:

(i) Gregg and the other 1976 decisions holding

that certain death penalty statutes can, if properly

administered to focus on the individual defendant,

meet the requirements of the Constitution;22

(ii) Woodson and the other 1976 decision hold

ing mandatory death penalty statutes unconstitutional

21 The first quote is in the Justice’s concurring opinion in Andres,

333 U.S. at 766; the second from Law and Literature (1931) cited in

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183, 199 (1971).

22 E.g. :

(i) In Gregg, this Court emphasized the constitutional

obligation to focus specifically on the defendant in at least six

places in the plurality opinion. 428 U.S. at 189-90, 190, 192, 197,

199 and 206.

(ii) In Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262 (1976) this Court

upheld the statute because it “guides and focuses the jury’s

objective consideration of the particularized circumstances of the

individual offense and the individual offender before it can impose

a sentence of death”. 428 U.S. at 274 (emphasis added).

(iii) In Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242 (1976), the statute

was held constitutional in part because the sentencing authority

must “ focus” on “the circumstances of each individual homicide

and individual defendant”. Id. at 258.

23

because they exclude consideration of mitigating fac

tors and the circumstances of the defendant;23 and

(hi) Lockett v. Ohio, _ U.S. No. 76-6997,

slip op. (July 3, 1978), which held that in death cases

the sentencing authority must be given a “full

opportunity” to consider “mitigating circumstances”,

including “any aspect of the defendant’s character

and record”. Id. at 17.

B. The Term “Mitigating” Was Not Defined for the

Jury and Concrete Examples of Mitigating Circumstances

Were Not Provided.

Buried in the last sentence of the first paragraph of

the death penalty charge is a blind reference to the word

“mitigating” (App. at 30a).

To slip into one sentence the single word “mitigating”

without any explanation is to give no “direction” or

“guidance” at all—and certainly falls far short of the

careful, adequate and suitable guidance and direction that

is constitutionally required.

Even had the word been emphasized rather than

buried, the legal term “mitigation” is not sufficiently

meaningful to a jury of lay persons. In contrast to the

obscure one word legalism buried away in Morgan’s

23 See:

(i) E.g., Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976),

“A process that accords no significance to relevant facets of the

character and record of the individual offender” is uncon

stitutional because it excludes from consideration the possibility

of “compassionate or mitigating factors stemming from the

diverse frailties of humankind”. Id. at 304.

(ii) Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S. 325 (1976) (“no meaningful

opportunity” for “consideration of mitigating factors” presented by

“the particular crime or by the attributes of the individual offender”.)

Id. at 333-34.

24

charge, the jury in Gregg was given a definition of the term

“mitigating”.24

In addition, this Court’s decisions—and a fair reading

of the Constitution—call for more than a definition of

“mitigating”. They require that particular mitigating

factors, relevant in light of the record, be called to the

jury’s specific attention as examples of what they could

weigh against the aggravating circumstances which the

court did call to the jury’s attention.

Here there were at least three such factors—Morgan’s

youth, his claim that he shot Gray because of duress

(High’s threat to kill him if he did not), and his lack of a

prior criminal record.25 26

In Gregg, this Court assumed that such factors would

be specifically called to the sentencing authority’s atten

tion. Under a fair reading of the constitutional require

ments in death cases they clearly should be.

The Georgia statute states flatly that the trial judge

“shall include” in his instructions “any mitigating circum

stances.” Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534.1.2® This Court, in

24 The jury was told that the term covered circumstances “which

do not constitute a justification or excuse for the offense in question,

but which, in fairness and mercy, may be considered as extenuating or

reducing the degree of moral culpability or punishment”. Record,

Trial Transcript at 480, Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 ( 1976).

The same definition was used in Coker v. Georgia, 433 U S 584

590-91 (1977).

25 Footnote 44 in Gregg sets forth, inter alia, the proposed

mitigating circumstances from the Model Penal Code, which include

as items (a), (f) and (g) the items which should have been

specifically included here for Morgan’s jury to “consider”. 428 U S at

193-94.

26 The statute, more fully, provides that “the judge shall consider

or he shall include in his instructions to the jury for it to consider, any

mitigating circumstances or aggravating circumstances otherwise au

thorized by law and any of the following statutory aggravating

circumstances which may be supported by the evidence.. . . ”

While it is not clear whether either the words “otherwise

authorized by law” or “which may be supported by the evidence”

25

upholding the Georgia scheme, repeatedly assumed that

that would, and should, be done. 428 U.S. at 164, 192,

193, 194 n.44,27 28 197. Indeed, in one of the many passages

which state that the jury’s attention must be “focused on

the characteristics of the person who committed the

crime” (point A above), this Court gave examples of what

it expected the jury’s attention to be “focused” upon.

Those included factors present in this cast —i.e., whether

the defendant had “a record of prior convictions for

capital offenses”, and “any special facts about this defend

ant that mitigate against imposing capital punishment

(e.g., his youth . . . . ) ”. Id., at 197.28

serve to modify, specify, or limit the duty to “include” “any”

mitigating circumstances in the instructions, it is clear that the Georgia

statute creates the duty to mention to the jury any relevant mitigating

circumstances for it to “consider”.

27 In the body of the opinion the court rebutted the contention

that standards to guide a jury’s discretion could not be formulated by

referencing the Model Penal Code’s listing of the “main circum

stances” of mitigation and aggravation which “should be weighed and

weighed against each other”.

28 That focus upon mitigating circumstances can make a life or

death difference is evident from the following analysis of the pool of

cases available to the Supreme Court of Georgia for comparison

purposes at the end of 1977:

(i) 36 of the 48 offenders for whom either youth, or lack of a

prior criminal record was reported as a mitigating factor by the

trial judge (where the death penalty was imposed), or by the

court’s assistant (where it was not), received life sentences (see

App. T, Tables 1 and 2):

(ii) the two offenders for whom both youth and no prior

record were reported received life sentences (despite the fact that

in both cases (Sanders v. State, 235 Ga. 425, 219 S.E.2d 768

(1976) and Stovall v. State, 236 Ga. 840, 225 S.E.2d 292

(1976)) the offenders were found guilty of brutal murders;

(iii) there are no cases where youth, no record, and evidence

of duress are reported, see note at p. 35 infra.

The need to make some reference to Morgan’s claim of duress

was particularly compelling here since the trial judge had just finished

telling the jury in his instructions on the merits that duress was

irrelevant to a charge of murder (App. at 23a).

26

C. The Jury Also Was Not Informed That It Should

Weigh “Mitigating” Circumstances Against Aggravating

Circumstances.

Apart from not defining the legalism “mitigating” for

the jury or providing particularized examples, the jury

instructions are also constitutionally deficient in that the

jury was not specifically informed that it should weigh

mitigating against aggravating circumstances. In contrast,

under the Model Penal Code referenced in Gregg, and

under the Florida statute approved in Proffitt, the sen-

tencer is specifically informed that it should weigh mitiga

ting against aggravating circumstances, 428 U.S. at 248-

251, 258. Similarly, in Jurek the question which a jury

must answer before imposing the death sentence neces

sarily requires such balancing. This Court in Coker also

assumed such an instruction was required, 433 U.S. at

589-91.

While a particular form of words may not con

stitutionally be required, surely it is not constitutional to

leave the jury totally at sea as it was left here.

D. The Jury Also Was Not Told That It Could Impose

a Life Sentence Even i f It Found One of the Statutory

Aggravating Circumstances. Indeed, the Overall Impact of

the Charge Was To Suggest It Could Not.

Most of the death penalty charge was devoted to

discussion of possible statutory aggravating circum

stances—at least one of which must be found by the jury

before it is authorized to consider imposing the death

penalty. Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534.1 (c).

But the trial judge did not tell the jury that even if it

found such a circumstance it could nonetheless decide to

impose a life sentence.

This particular deficiency was emphasized by the

three judges who dissented below.

27

Such a charge departs from Gregg (where the jury

was so informed29), and ignores the statutory scheme

which this Court held made the Georgia scheme con

stitutional.30 Indeed, it turns this statute into an uncon

stitutional mandatory death sentence scheme whenever a

jury concludes that one of the statutory aggravating

circumstances is present.

E. The Decision Below is Based Upon Misunder

standing of This Court’s View of the Constitutional

Requirements in Death Cases.

The Georgia Supreme Court, in its 4-3 decision in this

case, relied on its 5-2 decision a few days earlier in Spivey

v. State, 241 Ga. 477, 246 S.E.2d 288 (1978), cert, denied,

No. 78-5460, slip op. (December 4, 1978). Spivey,

without a single mention of Gregg, relied upon this Court’s

decision in Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262 (1976), to

approve an instruction that did not even mention the word

“mitigating”.

But the Texas scheme is significantly different from

Georgia’s, and the difference makes constitutionally fal

lacious the reasoning of the Georgia court. Under the

Texas statute, the questions which a sentencing jury has to

answer necessarily focus attention upon “particularized

mitigating factors” and the scheme thus “guides and

focuses the jury’s objective consideration of the particu

larized circumstances of the individual offense and the

individual offender”. Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. at 272, 274

(emphasis supplied). But the Georgia scheme does not

29 In Gregg, the trial judge first defined the relevant statutory

aggravating circumstances, then said that, if one was found, the jury

could “consider” imposing a death sentence, and then told them they

would consider aggravating and mitigating circumstances (defining

the term and giving examples) in actually making their decision.

Record, Trial Transcript, at 458, 478-80.

30 Ga. Code Ann. §27-2503(b) specifically requires that after

“appropriate instructions”, the jury shall determine whether any

mitigating or aggravating circumstances exist, and it then adds—“and

whether to recommend mercy for the defendant.”

28

do so, absent instructions of the sort present in Gregg but

lacking here.31

The dissent in Spivey concluded that the “incoming

tide of death penalty cases” had “worn away the court’s

resolve” to insist upon appropriate instructions where life

was at stake. We cannot comment on the Georgia court’s

motive. But such a “tide” makes it all the more important

that this Court hear this case. And we submit that what

has really been “worn away” are this Court’s rulings in

Gregg.

III . T H E D E A T H P E N A L T Y I N S T R U C T I O N S A L S O R A IS E

T H E I M P O R T A N T A N D R E C U R R IN G Q U E S T I O N A S T O

W H E T H E R , W H E R E T H E S T A T U T O R Y S C H E M E P R O V ID E S

T H A T T H E J U R Y ’S D E C IS IO N O N D E A T H M U S T B E F O L

L O W E D B Y T H E T R IA L J U D G E , T H E J U R Y M A Y N O N E T H E

L E S S B E L E D T O B E L IE V E T H A T I T S R O L E I S O N L Y T O

“ R E C O M M E N D ” O R “ A S K ” F O R D E A T H .

If a Georgia jury votes in favor of death the trial

judge must order execution.32

Here, however, the trial judge’s last statement to the

jury as to its role was that it must decide whether to

“recommend” the death penalty. Previously the judge

had instructed the jury that if it decided on death the form

of its verdict should be: “we recommend his punishment

as death”. And when the jury returned it said: “We ask

the death penalty”. (App. at 33 and 35a.)

While in other, earlier parts of the instructions the

Court also used the word “fix” (and indeed said if they

31 In the course of looking at a case arising in another jurisdiction

with a different statutory scheme, the Georgia court would have found

more relevant enlightenment in Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242

(1976), whose procedures were characterized by this Court as “like”

Georgia’s. Id. at 251, 259. There, Furman was said to be satisfied

because the sentencing authority’s discretion would be “guided and

channelled” by requiring examination of “specific factors that argue in

favor of or against imposition of the death penalty”, and by requiring

“ focus” on the “individual characteristics” of “each defendant” as

well as the particular crime. Id. at 258.

32 Ga. Code Ann. §27-2514; see Mason v. State, 236 Ga. 46, 222

S.E.2d 339, 342, (1975), cert, denied, 428 U.S. 910 (1976).

29

did fix punishment by death a sentence of death by

electrocution would be required), this is no cure.

“Particularly in a criminal trial, the judge’s last word is apt

to be the decisive word”.33 Moreover, it is clear from their

own words that the jurors in fact believed that their actual

function was to “ask” for death, not to decree death.

Does the confusion make a constitutional difference?

It should.

The death penalty is unique and irreversable. The

“responsibility of decreeing death” is “truly awesome”.

Lockett v. Ohio, No. 76-6997, slip op. (July 3, 1978).

Those who have that responsibility should know they

do.34

Both the Georgia Supreme Court and this Court have

recognized, in other contexts, that a death penalty jury

may decide differently depending on whether or not it

believes its word controls. Thus, in Georgia, death

sentences have been reversed where the prosecutor argued

to the jury that its decision would be reviewed on ap

peal.35 Similarly, in Dohbert v. Florida, 432 U.S. 282

(1977), Mr. Justice Rehnquist’s opinion for the Court

reasoned (in rejecting an argument based on change in

the Florida law) that

“. . . The jury’s recommendation may have been

affected by the fact that the members of the jury were

33 Bollenbach v. United States, 326 U.S. 607, 612 (1946). See

also Smith v. United States, 230 F.2d 935, 939 (6th Cir. 1956) (the

fact that one part of the charge is correct does not cure a later

inconsistency). Accord, United States v. Pope, 561 F.2d 663 (6th Cir.

1977); Perez v. United States, 297 F.2d 12, 16 (5th Cir. 1961).

34 As is indicated by Profitt, it is not constitutionally required that

a jury make the death decision. But what is required is that whichever

person or body in fact has that awesome responsibility should know

that its decision will determine the sentence.

33 See, e.g., Hawes v. State, 240 Ga. 327, 240 S.E,2d 833 ( 1977);

Fleming v. State, 240 Ga. 142, 240 S.E.2d 37 (1977); Prevatte v.

State, 233 Ga. 929, 214 S.E.2d 365 (1975).

30

not the final arbiter of life and death. They may have

chosen leniency when they knew that that decision

rested ultimately on the shoulders of the trial judge,

but might not have followed the same course if their

vote were final.” 432 U.S. at 294, n, 7.

A fortiori, where, as here, the jury was erroneously

led to believe that the trial judge would be the “final

arbiter” it “may” have been more willing to “ask” for

death, particularly in a case where there had been very

substantial local publicity.

All human experience points in that direction. As one

potential juror said, when asked if he supported the death

penalty, “its one thing saying and doing is another” (Tr.

56-57). But here the trial judge led the jury to believe that

they would do the saying and let someone else decide on

the doing.

The instinct to wash one’s hands of life or death

decisions is as old as Pontius Pilate. No doubt the

Members of this Court have themselves felt the difference

between the discussion of death and the decision to put

someone to death. Perhaps the difference cannot be

scientifically proven, but the risk is nonetheless real. And

in this country we do not let the courts take risks with life.

IV . C O N T R A R Y T O T H I S C O U R T ’S E X P E C T A T IO N S A S

E X P R E S S E D IN GREGG, T H E G E O R G IA C O U R T S H A V E N O T

N A R R O W E D T H E V A G U E A N D O V E R B R O A D S T A T U T O R Y

A G G R A V A T IN G C IR C U M S T A N C E U S E D A G A IN S T P E T IT IO N

E R . T H U S , H I S D E A T H S E N T E N C E W A S , F O R T H A T A D D I

T IO N A L R E A S O N , T H E U N C O N S T IT U T IO N A L R E S U L T O F

U N F E T T E R E D J U R Y D IS C R E T IO N .

Under the Georgia statutory scheme, the jury must

find at least one “aggravating” circumstance before a

death sentence can be imposed. The jury here found only

one of the circumstances enumerated in the statute, and

that circumstance is unconstitutionally vague and over

broad.

31

The seventh aggravating circumstance provided for in

the Georgia statute, and found by the jury here, is that the

offense be

“outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible or in

human in that it involved torture, depravity of

mind, or an aggravated battery to the victim.”

Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534.1(b)(7).

This Court recognized in Gregg that this language could

be construed to cover any murder, a construction which

would clearly make the provision overbroad. 428 U.S. at

201. This Court assumed, however, that the Georgia

courts would narrow the provision’s facially overbroad

language. That assumption was supported, the plurality

reasoned, by McCorquodale v. State, 233 Ga. 369, 211

S.E.2d 577 ( 1974), the only pre-Gregg- decision upholding

a jury’s death sentence based solely on the seventh

aggravating circumstance. That case was characterized by

this Court as a “horrifying, torture murder”, 428 U.S. at

201.36

Contrary to this Court’s expectations, the seventh

circumstance has not been narrowed. Rather, the Georgia

Supreme Court has, in its decisions since Gregg and in this

case, left the provision’s application to the unguided

discretion of juries.

Within two weeks of this Court’s decision in Gregg,

the Georgia Supreme Court discussed the seventh circum

stance in Banks v. State, 237 Ga. 325, 227 S.E.2d 380

(1976), cert, denied, 430 U.S. 975 (1977). Dividing 4-2

(with the seventh justice voting to hold Georgia’s death

penalty generally unconstitutional), the court held that the

jury’s finding of the seventh circumstance was supportable

36 McCorquodale involved the strangulation of a 17 year old

female victim after the defendant had, over a substantial period, beat,

whipped, burnt, bit and cut his bound victim, put salt in her wounds,

and sexually abused her.

32

where the two victims were each successively shot, first in

the back and then, after time for reloading, again in the

head. This time interval—not present here—was said to

permit a finding of “torture to at least one of the victims”

as well as “depravity of the mind” 227 S.E.2d at 382. In

dissent, Justice Hill stated

“In my view, the majority in this case has now

adopted an open-ended construction on ground 7 and

has placed at least that ground of our statute in peril

of being held invalid as being vague and overbroad

and thus capable of capricious and unconstitutional

application.” Id. at 384.

Thereafter, in Harris v. State, 237 Ga. 718, 230

S.E.2d 1 (1976), cert, denied, 431 U.S. 933 ( 1977), the

Court simply noted that the terms used in the seventh

circumstance were defined in “ordinary dictionaries,

Black’s Dictionary, or Words and Phrases”. 230 S.E.2d at

10. Although the court stated that it had “no intention” of

allowing the circumstance to become a “catchall”, its

reference to the dictionaries and legal phrase books (a)

indicates a lack of appreciation of Gregg’s expectation that

narrowing would occur, and ( b) would hardly be of help

to juries without explanatory instructions.

Here, the jury was given no guidance whatsoever on

any of the many broad terms except for “aggravated

battery”, where what was said (App. at 31a) was the

functional equivalent of saying that any shooting by the

defendant himself would be covered—precisely what this

Court in Gregg suggested would be overbroad.

Apart from the failure to explain or narrow the terms

“torture”, “depravity of mind”, “aggravated battery”,

“outrageously or wantonly”, “vile”, “horrible”, or “in

human”, and the concomitant risk that the jury in its

unbridled discretion could apply the words to “any mur

der”, here there was in fact no evidence of torture,