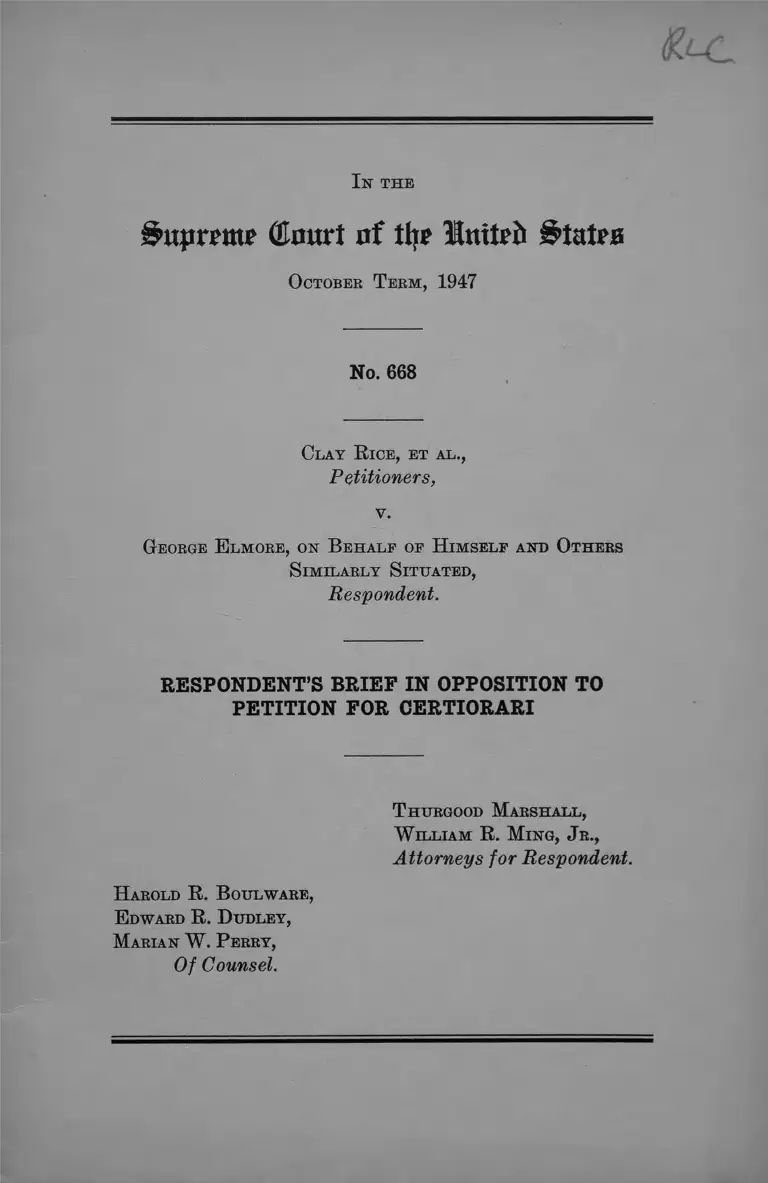

Rice v Elmore Brief Opposition to Petition Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1947

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rice v Elmore Brief Opposition to Petition Certiorari, 1947. e8a67125-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5a86203f-5659-4c6b-a35e-c4f00d702f7f/rice-v-elmore-brief-opposition-to-petition-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I k the

£>u;mw ©curt o f the llmteh §>tatPB

October T erm, 1947

No. 668

Clay R ice, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

George E lmore, ok Behalf of H imself akd Others

S imilarly Situated,

Respondent.

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

T hurgood M arshall,

W illiam R. M ikg, Jr.,

Attorneys for Respondent.

H arold R. B oulware,

E dward R. D udley,

Mariak W . P erry,

Of Counsel.

INDEX

PAGE

Statement of the Case___________________________________________ 1

Reasons for Denying the Petition_______________________________ 2

Conclusion ______________________________________________________ 9

TABLE OF CASES

Carolina National Bank of Columbia v. State, 38 S. E. 629________ 8

Chapman v. King, 154 F. (2d) 460_________________________________ 8

Ex parte Siebold, 100 U. S. 371_____________________________________ 4

Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651________________________________ 2

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45_________________________________ 7

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347______________________________ 7

In re Coy, 127 U. S. 731___________________________________________ 4

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. (2d) 212 certiorari

denied, 326 U. S. 721__________________________________________ 6

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268_____________________________________ 7, 9

Logan v. United States, 313 U. S. 299______________________________ 4

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501__________________________________ 6

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649___________ 7

Steele v. Louisville and Nashville R. R., 323 U. S. 192_____________ 6

Swafford v. Templeton, 185 U. S. 487______________________________ 4

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, 323 U. S. 210_____ 6

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299___________________________ 2

United States v. Mosley, 238 U. S. 383____________________________ 4

Wiley v. Sinkler, 179 U. S. 58_____________________________________ 4

I n the

Supreme Court o f thr Imtrfc i>tat?o

Octobek T eem, 1947

No. 668

Clay E ice, et al.,

Petitioners,

v .

George E lmore, on B ehalf of H imself and Others

S imilarly S ituated,

Respondent.

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioners in their petition and brief have correctly cited

the case below and have properly indicated the basis for

jurisdiction. In their statement of facts, however, they

have omitted certain matters.

As the court below found:

“ For half a century or more the Democratic Party

has absolutely controlled the choice of elective officers

in the State of South Carolina. The real elections

within that state have been contests within the Demo

cratic Party, the general elections serving only to ratify

and give legal validity to the party choice. So well has

this been recognized that only a comparatively few

persons participate in the general elections. In the

election of 1946, for instance, 290,223 votes were cast

for Governor in the Democratic primary, only 23,326

in the general election.” (E. 115)

2

Despite the fact that in 1944 the General Assembly of

South Carolina repealed all existing statutes which con

tained any reference directly or indirectly to primary elec

tions within the state, the District Judge expressly found:

“ In 1944 substantially the same process was gone

through, although at that time and before the State

Convention assembled, the statutes had been repealed

by action of the General Assembly, heretofore set out.

The State Convention that year adopted a complete new

set of rules and regulations, these however embodying

practically all of the provisions of the repealed statutes.

Some minor changes were made but these amounted to

very little more than the usual change of procedure in

detail from year to year. * * * (R. 94)

“ In 1946 substantially the same procedure was used

in the organization of the Democratic Party and another

set of rules adopted which were substantially the sam e

as the 1944 rules, excepting that the voting age was low

ered to 18 and party officials were allowed the option

of using voting machines, and the rules relative to ab

sentee voting were simplified * * (R. 95)

REASONS FOR DENYING THE PETITION

When the courts below upheld the right of respondent, a

qualified elector, to participate in the choice of congressmen

in South Carolina, they properly applied the relevant provi

sions of the Constitution and laws of the United States as

construed by this Court. They readily and rightly recog

nized that the question was one which has already been “ set

tled by this court * * *.” Therefore, we submit, the petition

for writ of certiorari should be denied.

This Court pointed out in United States v. Classic, 313

U. S. 299, 314, that ever since Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S.

651, it has uniformly held that under Article I, Sec. 2 of the

Constitution the right to choose congressmen “ is a right

established and guaranteed by the Constitution and hence

is one secured by it to those citizens and inhabitants of the

state entitled to exercise the right.”

3

This Court made it equally plain in the Classic case that

the constitutional protection of the right to vote extended

to certain primary elections when it said:

“ Where the state law has made the primary an in

tegral part of the procedure of choice, or where in fact

the primary effectively controls the choice, the right of

the elector to have his ballot counted at the primary is

likewise included in the right protected by Article I, Sec.

2. And this right of participation is protected just as

is the right to vote at the election, where the primary is

by law made an integral part of the election machinery,

whether the voter exercises his right in a party primary

which invariably, sometimes or never determines the

ultimate choice of the representative. Here, even apart

from the circumstance that the Louisiana primary is

made by law an integral part of the procedure of choice,

the right to choose a representative is in fact controlled

by the primary because, as is alleged in the indictment,

the choice of candidates at the Democratic primary de

termines the choice of the elected representative. More

over, we cannot close our eyes to the fact, already men

tioned, that the practical influence of the choice of

candidates at the primary may be so great as to affect

profoundly the choice at the general election, even

though there is no effective legal prohibition upon the

rejection at the election of the choice made at the pri

mary, and may thus operate to deprive the voter of his

constitutional right of choice.” (313 U. S. 299, 318-319.)

Italics supplied.

The record in the instant case shows, without dispute,

that the Democratic primary in South Carolina “ effectively

controls the choice” of congressmen and has done so for

nearly fifty years (R. 103-104). Equally clearly the record

shows that petitioners prevented respondent, and others

similarly situated, solely on account of his race and color,

from exercising his constitutional right to participate in the

choice of congressmen in the 1946 Democratic primary.

This Court held in the Classic case that Secs. 19 and 20 of

the Cirminal Code (Title 18 Secs. 51 and 52) provided crim

4

inal sanctions for interference with the right to vote in the

Louisiana primary. We submit that the courts below rightly

held that Title 8, Secs. 31 and 43 and the provisions of Title

28, Secs. 41 (1), (11), (14), and 400 similarly afford re

spondent a civil remedy in the federal courts for deprivation

of his right to vote in the South Carolina primary.

In support of their plea for certiorari petitioners claim,

primarily, that there was no “ state action” here. Even

accepting that assumption arguendo and only for the mo

ment, this neither justifies petitioners’ interference with

respondent’s right to vote nor does it require this Court to

review the decision below. In the Classic case, supra, this

Court was explicit on the point. There it was said:

Obviously included within the right to choose, se

cured by the Constitution, is the right of qualified

voters within a state to cast their ballots and have them

counted at Congressional elections. This Court has con

sistently held that this is a right secured by the Consti

tution. Ex parte Yarbrough, supra; Wiley v. Sinkler,

supra; Swafford v. Templeton, supra; United States v.

Moseley, supra; see Ex parte Siebold, supra; In re Coy,

127 U. S. 731; Logan v. United States, 144 U. S. 263.

And since the constitutional command is without re

striction or limitation, the right, unlike those guaran

teed by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, is

secured against the action of individuals as well as of

states. Ex parte Yarbrough, supra; Logan v. United

States, supra. (313 U. S. 299, 315.)

Thus it appears to be well settled by the decisions of this

Court that the paramount right of a free people to choose

those persons to whom the powers of government are to be

entrusted is protected by the Constitution from interference

by individuals as well as by states. Petitioners take nothing

by their claim that their actions were done pursuant to the

“ rules” of a “ voluntary political association.” They de

liberately and admittedly so acted as to prevent qualified

electors from exercising their constitutional right to vote.

The courts below, then, followed the decisions of this Court

5

in holding that the petitioners thus violated the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States.

Petitioners confuse the rights protected by Article I, Sec.

2 of the Constitution with those protected by the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments. That confusion is understand

able. The whole course of official conduct in South Carolina

beginning with then Governor Johnston’s speech when he

called a special session of the Legislature in 1944 * was to

evade if possible, or to violate if necessary, the express

limitations of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

It was admittedly the intention of the governor and the leg

islature to deprive all Negroes of their right to vote in the

Democratic primary. Small wonder, then, that petitioners,

fully aware of this scheme, are preoccupied with the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments. We submit, however,

that it is at their peril that they ignore the protection af

forded all qualified electors by Article I, Sec. 2 of the Con

stitution.

We agree with petitioners that since the decision of the

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, this Court has held that the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments apply only when

there is “ state action.” And, the courts below, relying on

the decisions of this Court, found that it was the State of

South Carolina, acting through petitioners, which denied

respondent the right to vote. Thus respondent was entitled

to, and has been afforded, the protection of the Civil War

Amendments as well as the protection of Article I of the

Constitution.

It cannot be denied that it is a function of the state to

conduct elections for state and federal officers and the state

of South Carolina, of course, performs that function. As

the courts below found, in South Carolina the selection of

officers of government is a two-step process with the primary

the first step and the general election the second. Each

* See Exhibit C to original Complaint, which is admitted to be accurate

and correct (R. 37).

6

step, however, is an essential part in the process of selecting

the officers of government. This is so in South Carolina

whether the first step, the primary, is conducted pursuant

to statutes or to the rules of a political party, and the courts

below properly so held.

As the court below pointed out, when the officers of the

Democratic Party

“ participate in what is a part of the state’s election

machinery they are electing officers of the state de facto

if not de jure, and as such must observe the limitations

of the Constitution. Having undertaken to perform an

important function relating to the exercise of sov

ereignty of the people, they may not violate the funda

mental principles laid down by the Constitution for its

exercises. ’ ’

That conclusion was required by the decision of this Court

in the Classic case since “ in fact the primary effectively con

trols the choice.”

In other cases, this Court has recognized that it is not the

symbols and trappings of officialdom which determine

whether the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments apply

but rather whether the facts of the particular case disclose

the exercise of the state’s authority. For example, in Marsh

v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, this Court held that the Four

teenth Amendment operated on the private owner of a

“ company town” to protect the right of freedom of speech.

Labor unions, although private voluntary associations, have

been held by this Court subject to the limitations of the due

process clause of the Constitution when exercising power

conferred by the federal government. Steele v. Louisville

and Nashville RR, 323 TJ. S. 192, Tunstall v. Brotherhood of

Locomotive Firemen, 323 U. S. 210. Similarly the Fourth

Circuit in Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. (2d)

212,* held that where a corporation had invoked the power

* Certiorari denied, 326 U. S. 721.

7

of the state for its creation and relied upon city funds for

its operation it was in fact a state instrumentality.

As this Court declared in Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S.

649, 664-665:

“ When primaries become a part of the machinery for

choosing officials, state and national, as they have here,

the same tests to determine the character of discrimina

tion or abridgement should be applied to the primary

as are applied to the general election. If the State re

quires a certain electoral procedure, prescribes a gen

eral election ballot made up of party nominees so chosen

and limits the choice of the electorate in general elec

tions for state offices, practically speaking, to those

whose names appear on such a ballot, it endorses, adopts

and enforces the discrimination against Negroes, prac

ticed by a party entrusted by Texas law with the de

termination of the qualifications of participants in the

primary. This is state action within the meaning of the

Fifteenth Amendment. Guinn v. United States, 238 U.

S. 347, 362.

“ The United States is a constitutional democracy.

Its organic law grants to all citizens a right to partici

pate in the choice of elected officials without restriction

by any State because of race. This grant to the people

of the opportunity for choice is not to be nullified by a

State through casting its electoral process in a form

which permits a private organization to practice racial

discrimination in the election. Constitutional rights

would be of little value if they could be thus indirectly

denied. Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 275.

‘ ‘ The privilege of membership in a party may be, as

this Court said in Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45, 55,

no concern of a State. But when, as here, that privilege

is also the essential qualification for voting in a primary

to select nominees for a general election, the State

makes the action of the party the action of the State. ’ ’

Prior to the action of the South Carolina Legislature in

repealing more than 150 statutes governing the conduct of

the primary in that state there was no doubt that under the

8

decision in Smith v. Allwright, supra, respondent had a right

to participate in the Democratic primary. The court below

expressly found that in fact the relationship between the

Democratic primary and the process of the selection of the

officers of government was unchanged by the repeal of the

statutes (R. 103). Under these circumstances, we submit,

petitioners continued to exercise the power of the state in

carrying on the election of representatives. In so doing

they were bound by the limitations of the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments and in accordance with the decisions

of this Court the courts below properly so held.

Petitioners claim that the decision of the court below is

inconsistent with that of the Fifth Circuit in Chapman v.

King, 154 F. (2d) 460. In that case, relying on Smith v.

Allwright, supra, the court upheld the right of a Negro voter

to participate in the Georgia Democratic primary. At most

it can be said that there is dicta in the opinion in Chapman

v. King, 154 F. (2d) 460, 463, which is inconsistent with the

decision of the court below in the instant case. When a

decision is consistent with the decisions of this Court a dif

ference in dicta in the opinion of another Circuit Court of

Appeals is not, we submit, ground for granting a writ of

certiorari. Particularly is that true when, as here, the de

cisions of the two courts are consistent with each other and

the rulings of this Court.

Similarly, the petitioners seek to bolster their plea by

claiming that the court below has decided an important

question of “ local law” in a way probably in conflict with

applicable local decisions. The court below construed and

applied the relevant provisions of the Federal Constitution

and statutes. By definition the limitations of the Constitu

tion of the United States are not “ local” in character.

Therefore Carolina National Bank of Columbia v. State, 38

S. E. 629, has no application. It is for the federal courts,

not the Supreme Court of South Carolina, to decide whether

there has been “ state action” within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment. We submit that it has already

9

been demonstrated that the decision of the court below was

consistent with the decisions of this Court in that regard.

Petitioners also contend that the decision of the Court

below interferes with their right peaceably to assemble and

thus contravenes the First Amendment to the Constitution.

This contention is as spurious as it is novel. The actual

“ right” which petitioners assert is the absolute authority

to deprive Negroes in South Carolina of the effective exer

cise of their ‘ ‘ right to choose members of the House of Rep

resentatives.” The record in this case shows plainly that

in conducting the primary election in the State of South

Carolina the Democratic Party is not a group of individual

citizens assembling peaceably to secure redress for griev

ances. It is an organization carrying on a part of the func

tion of the state government to select representatives and

senators to sit in the Congress of the United States and it

is to that activity to which the court below applied the Con

stitutional limitations. In any event, petitioners’ right to

assemble cannot be so exercised so to deprive respondent of

his right to vote and this Court so held in Smith v. Allwright,

supra.

CONCLUSION

In Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 275, this Court pointedly

declared that the Fifteenth Amendment nullifies ‘ ‘ sophisti

cated as well as simple-minded modes of discrimination.”

Characterization of the South Carolina device to achieve

the disfranchisement of Negroes seems hardly necessary.

The record in this case shows plainly and without contradic

tion that the processes of that state have been subverted to

achieve a result forbidden by the Constitution of the United

States. Both the District Court and the Circuit Court of

Appeals recognized this and so held. That decision is con

sistent with the applicable decisions of this Court. We sub

mit, therefore, that no grounds exist here to warrant issu

10

ance of a writ of certiorari by this Court and we urge denial

of the petition.

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood M arshall,

W illiam R. M ing, Jr.,

Attorneys for Respondent.

H arold R. B oulware,

E dward R. D udley,

M arian W . P erry,

Of Counsel.