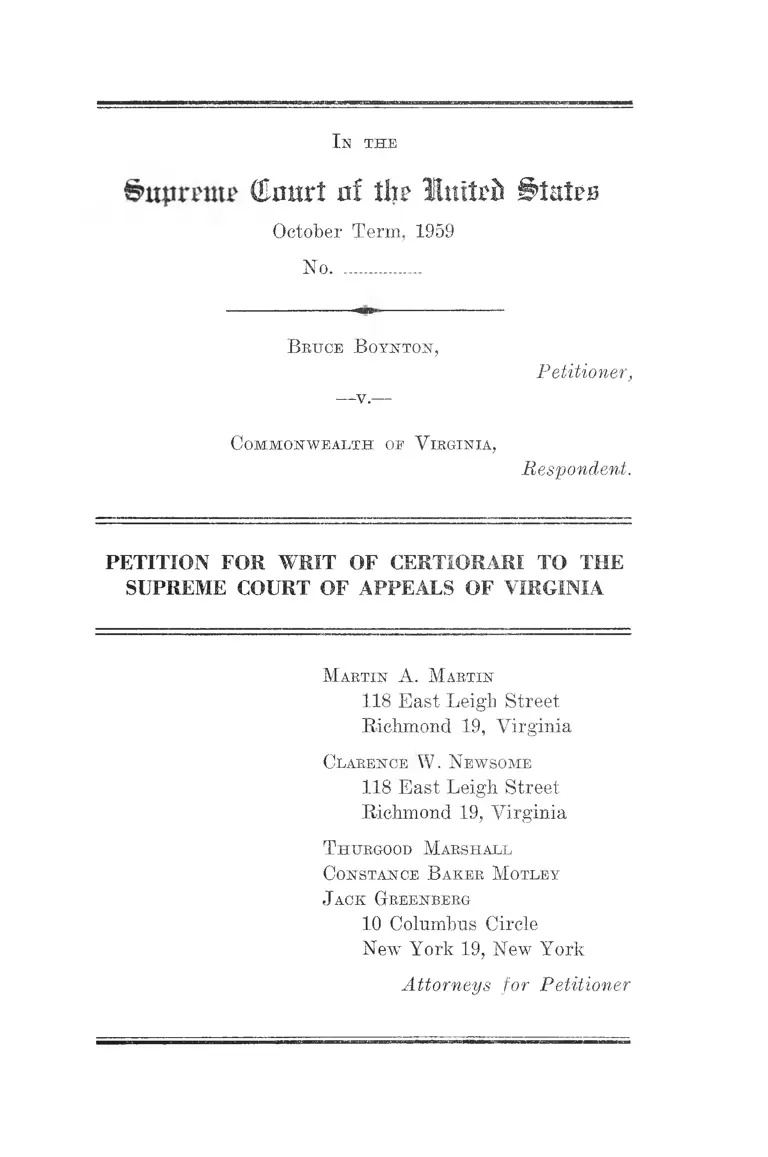

Boynton v. Virginia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boynton v. Virginia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, 1959. 00539b9c-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5bcd3161-4c0c-4566-9464-b2173f5180be/boynton-v-virginia-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-appeals-of-virginia. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

(Enurl of the llnitrit States

October Term, 1959

No_______

B ru ce B o y n to n ,

—v.—

Petitioner,

C o m m o n w ea lth oe V ir g in ia ,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

M a rtin A. M artin

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Clarence \Y. N ew som e

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

T hurgood M arshall

C onstance B aker M otley

J ack G reenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New' York 19, New York

Attorneys for Petitioner

I n t h e

jshtprpmp ( to r t of % Mniteb

October Term, 1959

No. ..............

B bu ce B o y n to n ,

—v.—

Petitioner,

C o m m o n w ea lth o r V ir g in ia ,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeals of the

Commonwealth of Virginia.

Opinions Below

No opinion was rendered in this case by the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia when it denied the petitioner

a writ of error to the judgment of the Hustings Court of

the City of Richmond on the 19th day of June, 1959. No

opinion was rendered by the Hustings Court of the City

of Richmond on the 20th day of February, 1959 when it

found petitioner guilty of a violation of §18-225 of the

Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended.

Judgment

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Vir

ginia was rendered on the 19th day of June, 1959 and a

stay of execution and enforcement of the judgment of said

2

Court was granted on the 24th day of July, 1959 staying

the execution and enforcement of same until the 17th day

of September, 1959, unless the case has before that time

been docketed in this Court in which event enforcement of

said judgment shall be stayed until the final determination

of this case by this Court.

Questions Presented

1.

Whether the criminal conviction of plaintiff, an inter

state traveller, for refusing to leave an interstate bus

terminal restaurant where he sought refreshment at a

regularly scheduled stop in the course of his interstate

journey and was barred solely because of his race, is invalid

as a burden on interstate commerce in violation of Article

I, §8, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution.

2 .

Whether said conviction violates the due process and

equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment of the

Constitution of the United States.

Constitution and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves:

Article I, §8, and the due process and equal protec

tion clauses of the XIV Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States.

§18-225 of the Code of Virginia of 1950. This statu

tory provision is set forth in the statement, infra,

p. 4.

3

Statement of the Case

Bruce Boynton, petitioner, a Negro student at the

Howard University School of Law, Washington, D. C.,

purchased a ticket, in Washington, D. C., for transportation

by Trailways Bus to Montgomery, Alabama, via Richmond,

Virginia, and then with connecting carrier to his home in

Selma, Alabama. He boarded a Trailways Bus in Washing

ton, D. C., at 8 :00 p. m., and arrived at the Trailways Bus

Terminal in Richmond, Virginia about 10:40 p. m. The

bus driver notified him and all other passengers that there

would be a forty minute layover at the Richmond Trailways

Terminal (R. 31-33).

Petitioner left the bus, entered the waiting room of the

terminal and noticed a small restaurant crowded with

colored patrons. He proceeded through the waiting room

and approached another restaurant, which was practically

empty, adjacent to the waiting room (R. 33). He entered

that restaurant, where the white waitress informed him that

he could not be served. She advised him to go to the colored

restaurant. He explained that the colored restaurant was

crowded, that he was an interstate passenger, and that he

desired to be served before boarding his bus which was due

to leave shortly (R. 34-35). She persisted in stating that

it was not the custom to serve Negroes in that particular

restaurant. He then inquired who could serve him. The

waitress called the assistant manager who demanded that

petitioner leave, and stated that he could not be served in

that restaurant because he was colored (R. 35).

When petitioner refused to leave the restaurant the as

sistant manager caused him to be arrested (R. 35) and

charged with a violation of §18-225 of the Code of Virginia

of 1950, as amended which provides:

4

“If any person shall without authority of law go

upon or remain upon the lands or premises of another

after having been forbidden to do so by the owners,

lessee, custodian or other person lawfully in charge of

such land, or after having been forbidden to do so by

sign, or signs posted on the premises at a place or

places where they may be reasonably seen, he shall be

deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction

thereof shall be punished by a fine of not more than

$100.00 or by confinement in jail not exceeding thirty

days, or by both such fine and imprisonment.”

The bus terminal was owned and operated by Trailways

Bus Terminal, Inc. (R. 9-17). The restaurants therein were

built into the terminal upon its construction and leased by

Trailways to Bus Terminal Restaurant of Richmond, Inc.

(R. 9-17). The lease gave exclusive authority to the lessee

to operate restaurants in the terminal, required that they

be conducted in a sanitary manner, that sufficient food and

personnel be provided to take care of the patrons, that

prices be just and reasonable, that equipment be installed

and maintained to meet the approval of Trailways, that

lessee’s employees be neat and clean and furnish service

in keeping with service furnished in an up-to-date, modern

bus terminal; prohibited the sale of alcoholic beverages on

the premises; and permitted cancellation of the lease upon

the violation of any of its conditions (R. 9-17).

Petitioner was convicted in the police court of the City

of Richmond and fined $10.00, which conviction was ap

pealed to the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond which

affirmed (R. 38). Petition for writ of error to the Supreme

Court of Appeals was rejected, the effect of which was to

affirm the judgment of the Hustings Court (R. 42). The

affirmance by the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, ap

pears in the Appendix, infra, p. 11. In the Hustings Court

5

of the City of Richmond petitioner objected to the criminal

prosecution on the grounds that it contravened his rights

under the Commerce Clause of the United States Consti

tution (Article 1, Section 8) and the Interstate Commerce

Act (Title 49 U. S. C., Section 316(d)) and that he was

thereby denied due process and equal protection of the

laws (R. 5). Said objections were renewed by notice of

appeal and assignment of error to the Supreme Court of

Appeals of Virginia (R. 3). These defenses, however, as

aforesaid, were rejected at all stages of the litigation with

out opinion.

Reasons Relied on for Allowance of the Writ

I. T h e decisions below con flic t w ith p r in c ip les estab lished

by decisions o f th is C ourt by d en y in g p e titio n e r , a N egro ,

a m eal in th e course o f a regu larly sch ed u led sto p at th e

restauran t te rm in a l o f an in tersta te m o to r carrier and co n

v ic ting h im o f trespass fo r seek in g nonsegrega ted d in in g

facilities w ith in th e term in a l.

In Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 this Court held that

Virginia could not require racial segregation on interstate

buses. The basis of the decision is that the enforcement

of such seating arrangements so disturbed Negro pas

sengers in interstate motor travel that a burden on inter

state commerce was created in violation of Article 1, Sec

tion 8 of the United States Constitution. Id. at 382. This

Court held that absent congressional legislation on the

subject the Constitution required “a single uniform rule

to promote and protect national travel.” Id. at 386. An

identical rule has been applied to similar racial restrictions

on commerce imposed by rules of the carrier enforced by

arrest and criminal conviction. Whiteside v. Southern Bus

Lines, 177 F. 2d 949 (6th Cir. 1949); Chance v. Lambeth,

186 F. 2d 879 (4th Cir. 1951), cert, denied 341 U. S. 941. It

6

is obvious that interstate bus travel cannot be conducted

without regularly scheduled rest stops and anyone who

has travelled for long distances on an interstate bus knows

that dining facilities at such stops are an essential part

of interstate bus service. In fact, in this ease the record

reveals that the Richmond Terminal, at which petitioner’s

arrest occurred, was designed to incorporate a restaurant

at the time of its construction (R. 9). To deny petitioner a

meal at the terminal obviously was as disturbing to him or

indeed far more disturbing than the shifting about of pas

sengers on a bus which this Court condemned in Morgan,

supra.

Petitioner here testified that the colored restaurant ap

peared to be crowded at the time he approached it during

the layover, while the white restaurant was not crowded

(R. 33). Although the assistant manager of the bus termi

nal restaurant testified that there was “seating capacity”

in the colored restaurant at or around the time petitioner

entered the white restaurant (R. 24) this apparent conflict

may be explained by the fact that passengers-customers

come and go: if petitioner had waited in the colored res

taurant he might have eventually been served. But it surely

is a burdensome discrimination in service to subject one

class of passengers to the uncertainty of waiting at a colored

restaurant for the chance of a seat while seats surely are

available at the white restaurant.

But petitioner’s objection to the police enforced segrega

tion is more fundamental. In Henderson v. United States,

339 U. S. 816, 825, this Court, while dealing with the

Interstate Commerce Act, condemned racial segregation in

railroad dining cars as “emphasizing] the artificiality of

the difference in treatment which serves only to call at

tention to a racial classification of passengers holding

identical tickets and using the same public dining facility.”

An interstate traveler finds such treatment as objectionable

7

in a terminal as he does on a moving diner. Moreover,

clearly even more disruptive of a smooth interstate journey

was petitioner’s arrest and conviction which enforced the

racial restriction see Morgan v. Virginia, supra. These

decisively interrupted the trip. That the restaurant in

question was leased by the terminal to a restaurant operator

hardly made the interruption of petitioner’s journey less

conclusive.

As the terminal’s lease to the restaurant operator indi

cates (R. 9), the lease was made prior even to the con

struction of the terminal. The restaurant was built as an

integral and essential part of the interstate facility. The

lessor imposed conditions on the lessee designed to as

sure adequate sanitary conditions, reasonably priced ser

vice for restaurant patrons, and the right to cancel the

lease upon violation of any of its conditions. Access to the

restaurant obviously facilitated interstate travel, and was

intended to. Conversely, exclusion impeded the smooth

flow of national commerce, notwithstanding internal pro

prietary arrangements within the terminal.

It cannot seriously be urged that because the terminal

is stationary or local as to some persons, it therefore is

not in interstate commerce at all and that petitioner’s

treatment for that reason did not constitute a burden on

interstate commerce. This Court has held that a transac

tion with a red cap at a railroad station is in interstate

commerce, N. Y. N. H. £ H. R. Co. v. Notlmagle, 346 U. S.

128. As stated in that case at p. 130, “Neither continuity

of interstate movement nor isolated segments of the trip

can be decisive. ‘The actual facts govern. For this purpose,

the destination intended by the passenger when he begins

his journey and known to the carrier, determines the char

acter of the commerce,’ ” citing Sprout v. South Bend, 277

U. S. 163, 168. Moreover, grain elevators surely as sta

tionary as the bus terminal have been held to be in inter-

8

state commerce. See Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331

U. S. 218, 229. And taxi service between two rail terminals

in Chicago which to the man in the street might look like

ordinary local taxi traffic also has been held to be in inter

state commerce. United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 332 U. S.

218, 228.

The operation of a bus terminal surely falls within the

principle of such cases at least insofar as it applies to

an interstate bus passenger who attempts to use its facili

ties in the usual manner in the normal course of an inter

state bus trip.

II. P e titio n e r’s co n v ic tio n w h ich served o n ly to en fo rc e the

racial reg u la tion o f th e bus te rm in a l restauran t con flic ts

w ith p r in c ip les estab lished by decisions o f th is C ourt.

If anything is fundamental in constitutional jurispru

dence it is that the state may not enforce racial regulations.

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, invalidated judicial enforce

ment of private racially restrictive covenants by court in

junction. Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249, held that

racially restrictive covenants could not be enforced by the

courts by assessing damages for their violation. Marsh v.

Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 held that the criminal courts could

not be employed to convict of trespass persons exercising

Fourteenth Amendment rights.

In this case petitioner conducting himself in a manner

entirely normal for an interstate passenger ran afoul of

the terminal restaurant’s racial rule. While he may bring

civil suit against the terminal for refusal to serve him, see

Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, supra, Chance v. Lam

beth, supra, Valle v. Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697 (3d Cir. 1949),

perhaps he might also have chosen to suffer the indignity

and discomfort and done nothing. But here the terminal

chose to invoke the power of the State, which readily com-

9

plied, to convict petitioner of a crime. Apart from the

fairly substantial penalty which could have been imposed

or the modest, but highly inconvenient penalty and attend

ing criminal proceedings in which he became embroiled,

it may be noted that he is a law student whose opportunity

for admission to the bar obviously will be complicated by

a criminal conviction on his record. At least to the extent

that the State criminal machinery has been used to enforce

discrimination, therefore, the judgment below conflicts with

the long, consistent line of decision in this Court, For

this reason, therefore, the writ of certiorari should be

granted to correct the grievous error and injustice com

mitted below.

Respectfully submitted,

M a rtin A. M artin

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Cla ren ce W . N ew som e

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

T hurgood M arshall

C onstance B a k er M otley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Petitioner

11

APPENDIX

Judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeals

V ir g in ia :

In the Supreme Court of Appeals held at the Supreme

Court of Appeals Building in the City of Richmond on

Friday the 19th day of June, 1959.

The petition of Bruce Boynton for a writ of error and

supersedeas to a judgment rendered by the Hustings Court

of the City of Richmond on the 20th day of February, 1959,

in a prosecution by the Commonwealth against Bruce Boy-

ington, alias Bruce Boynton, for a misdemeanor, having-

been maturely considered and a transcript of the record of

the judgment aforesaid seen and inspected, the court being

of opinion that the said judgment is plainly right, doth re

ject said petition and refuse said writ of error and super

sedeas, the effect of which is to affirm the judgment of the

said Hustings Court.

30