Plaintiffs' Amended Responses to Defendants' First Set of Interrogatories

Public Court Documents

February 19, 1991

57 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Amended Responses to Defendants' First Set of Interrogatories, 1991. e0b097d0-a146-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5bf16e64-c547-4156-8603-05f3a3860788/plaintiffs-amended-responses-to-defendants-first-set-of-interrogatories. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

® » = Loe |

{ - 4

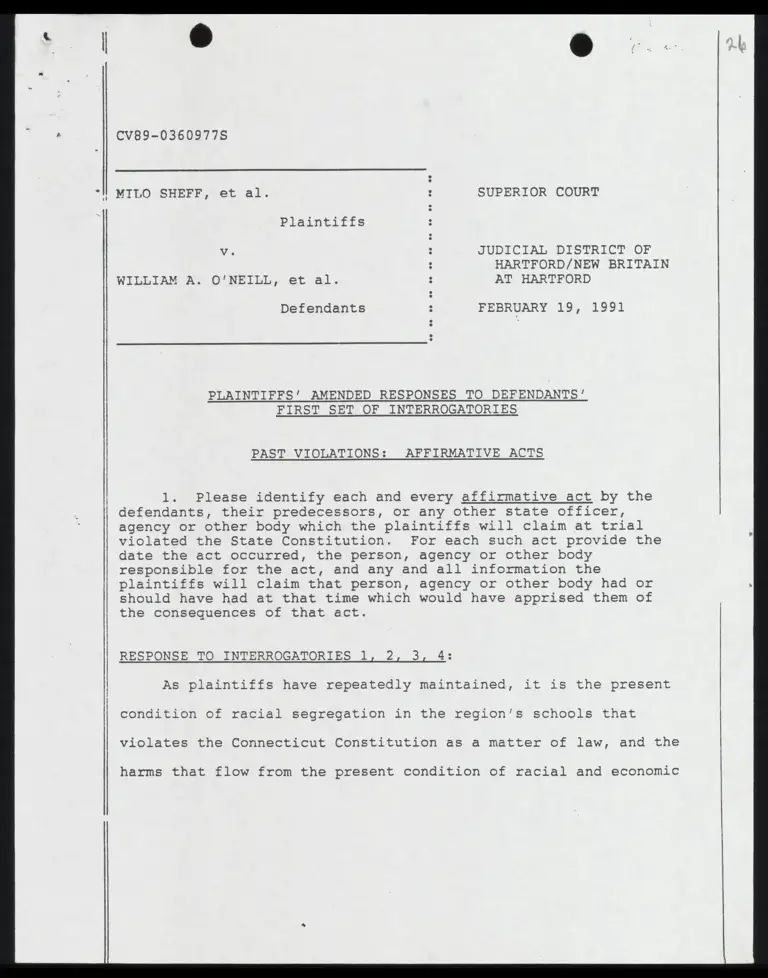

HE CvB89-0360977S

‘ll MIT.0O SHEFF, et al. : SUPERIOR COURT

Plaintiffs :

Vv. JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al. AT HARTFORD

Defendants FEBRUARY 19, 1991

PLAINTIFFS’ AMENDED RESPONSES TO DEFENDANTS’

FIRST SET OF INTERROGATORIES

PAST VIOLATIONS: AFFIRMATIVE ACTS

1. Please identify each and every affirmative act by the

defendants, their predecessors, or any other state officer,

agency or other body which the plaintiffs will claim at trial

violated the State Constitution. For each such act provide the

date the act occurred, the person, agency or other body

responsible for the act, and any and all information the

plaintiffs will claim that person, agency or other body had or .

should have had at that time which would have apprised them of

the consequences of that act.

RESPONSE TO INTERROGATORIES 1, 2, 3, 4:

As plaintiffs have repeatedly maintained, it is the present

condition of racial segregation in the region's schools that

violates the Connecticut Constitution as a matter of law, and the

harms that flow from the present condition of racial and economic

segregation that in fact deprive Hartford area school children of

their right to equality of educational opportunity.

Defendants have claimed that the requisite “state action” is

not present here, because, as they argue, the state has taken no

affirmative steps to cause segregation. As plaintiffs have tried

to impress upon the court, the state's argument has no basis in

law. The state controls public education, and the state has an

affirmative duty to guarantee equal educational opportunity. The

extensive involvement of the state satisfies every standard of

state action of which plaintiffs are aware.

Nonetheless, if defendants persist in this line of argument,

plaintiffs are prepared to show that defendants have taken

numerous actions that have “caused” or “contributed to”

segregation, and that defendants are responsible for existing

school boundaries that exacerbate segregation. Taken together,

in whole or in part, these actions by the state can be said to be

unconstitutional to the extent that they have led to or have

contributed to the unconstitutional system of racial and economic

segregation and the concomitant harm that flows from that system.

A summary of plaintiffs’ proof on these points is set out below,

as best as can be determined at this stage of the case.

Plaintiffs reserve the right to amend or supplement their

responses.

a. Detrendants are legally responsible for the

creation, maintenance, approval, funding,

supervision and control of public education.

Defendants discharge a broad range of statutory

obligations that demonstrate their control over and

responsibility for Connecticut's system of public education.

Defendants provide substantial financial support to schools

throughout the State to finance school operations. See §§10-262,

et seq. They also approve, fund, and oversee local school

building projects, see §§10-282, et seg., and reimburse towns for

student transportation expenses. See §10-273a.

Defendant State Board of Education has “general

supervision and control [over] the educational interests of the

state,” §10-4, and exercises broad supervision over schools

throughout the State. It prepares courses of study and curricula

for the schools, develops evaluation and assessment programs, and

conducts annual assessments of public schools. See id. The

Board also prepares a comprehensive plan of long-term goals and

short-term objectives for the Connecticut public school system

every five years. See id.

Defendants exert broad control over school attendance

and school calendar requirements. They establish the ages at

which school attendance is mandatory throughout the State. See

§10-184. They determine the minimum number of school days that

public schools must be in session each year, and have the

authority to authorize exceptions to this requirement. See §10-

15. They also set the minimum number of hours of actual school

work per school day. See §10-16. In addition, defendants

promulgate a list of holidays and special days that must be

suitably observed in the public schools. See §10-29a.

Defendants are directly involved in the planning and

implementation of required curricula for the State's public

schools. They promulgate a list of courses that must be part of

the program of instruction in all public schools, see §10-16b,

and they make available curriculum materials to assist local

schools in providing course offerings in these areas. See id.

Defendants impose minimum graduation requirements on high schools

throughout the State, see §10-22la, and they exercise supervisory

authority over textbook selection in all of the State's public

schools. See §10-221. In addition, defendants require that all

public schools teach students at every grade level about the

effects of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, see §10-19, and that they

provide students and teachers with an opportunity for silent

meditation at the start of every school day. See §10-16a.

Defendants exert broad authority over the hiring,

retention, and retirement, of teachers and other school

personnel. They set minimum teacher standards, see §10-145a, and

administer a system of testing prospective teachers before they

are certified by the State. See §10-145f. Certification by

defendants is a condition of employment for all teachers in the

Connecticut public school system. See §10-145. All school

business administrators, see §10-145d, and intramural and

interscholastic coaches hired must also be certified by

defendants. See §10-149. Defendants also prescribe statewide

rules governing teacher tenure, see §10-151, and teacher

unionization, see §10-153a, and maintain a statewide teachers’

retirement program. See §10-183c.

Defendants supervise a system of proficiency

examinations for students throughout the State. See §10-14n.

These examinations, provided and administered by the State Board

of Education, test all students enrolled in public schools. See

id. Defendants require students who do not meet State standards

to continue to take the examinations until they meet or exceed

expected performance levels. See id. Defendants also promulgate

procedures for the discipline and expulsion of public school

students throughout the State. See §10-233a et seq.

Defendants also exert broad authority over language of

instruction in public schools throughout the State. They mandate

that English must be the medium of instruction and administration

in all public schools in the State. See §10-17. But they also

require local school districts to classify all students according

to their dominant language, and to meet the language needs of

bilingual students. See §10-17f. Defendants require each school

implementing a program of bilingual education for the first time

to prepare and submit a plan for implementing such a program to

the State Commissioner of Education. See id.

The Connecticut Supreme Court has repeatedly stated that

public education is, in every respect, a responsibility of the

state. See Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Law in Opposition to

Respondents’ Motion to Strike (November 9, 1989) (pp. 7-15).

While certain aspects of administration are delegated to local

districts, such delegation is only at the pleasure of the state,

and in no way diminishes the state's ultimate duty to provide

public education. Plaintiffs will present evidence of the

history of state control over local education in Connecticut

through their expert historical witness, Professor Christopher

Collier.

b. The state requires, pursuant to C.G.S. §10-240, that

school district boundaries be coterminous with municipal

boundaries.

The requirement that town and school district boundaries

be coterminous was imposed by the state in 1909. Prior to 1809,

there was no state requirement that town and school district

lines be the same, and many school districts crossed town lines.

Since 1909, there has been no change in school district

boundaries in the Hartford region, even as those school districts

became increasingly segregated. Thus, the state-imposed system

of coterminous town and school district boundaries served as a

legal template on which the pattern of school segregation was

laid out.

Even in 1909, although Connecticut's black population

was very small, the pattern of black migration and racially

identifiable housing was already becoming established. By 1909,

roughly 92% of Connecticut blacks were living in the cities.

Thus, restriction of school districts to city boundaries had the

foreseeable impact of limiting black access to suburban schools.

The modern pattern of school segregation also traces its

foundations to a system of official segregation in the 19th

century.

The only exception to the requirement of coterminous

town and school district boundaries is where two or more

districts voluntarily enter into a regional school district with

state approval, pursuant to C.G.S. §10-39 et seq. However,

regionalization requires voluntary suburban participation.

There is no constitutional basis for the legal

requirement that town and school district boundaries be

coterminous. Nor is there any practical basis for the

requirement. Indeed, the requirement, as applied to the Hartford

metropolitan area, operates to maintain a system of racial and

economic segregation. School districts throughout the United

States are organized on other than a town-by-town basis. In

Connecticut, intertown arrangements have been approved,

: encouraged, or mandated by the state, in the areas of sewer,

water, transportation, and education. In the area of education,

the state has established regional vocational-educational

schools, and has encouraged interdistrict cooperative

arrangements among suburban communities in special education

programs. However, since 1954, with the exception of Project

Concern, which the state has failed to adequately fund (see

response to Interrogatory 5), the state provided little or no

funding for urban/suburban interdistrict programs in regular

education until after the present lawsuit was announced.

c. The state requires, pursuant to C.G.S. §10-184,

that school-age children attend public school

within the school district wherein the child

resides.

Pursuant to C.G.S. 10-184, parents are required to send

their children seven and over and under sixteen to a school “in

the district wherein such child resides.” Defendants have

enforced this statute to prevent children living in the city of

Hartford from attending school in suburban districts. For

example, in 1985, four parents living in Hartford sent their

children across town lines to the Bloomfield school system in

order to secure an integrated and minimally adequate education

for their children. The State, with the knowledge that the

system of education these children were receiving was better in

Bloomfield, employed the criminal process and had the parents

arrested for larceny pursuant to C.G.S. 53a-119. See State v.

Saundra Foster, et al. (spring 1985).

Plaintiffs will also present historical evidence that

prior to the adoption of C.G.S. §10-184, school children in

Connecticut, and particularly, in the Hartford region, often

crossed district lines to obtain education.

d. From approximately 1954 to the present, the

Department of Education and the State Board

Education have engaged in a massive program

school construction and school additions or

renovations in Hartford and the surrounding

communities, with direct knowledge of the

increasing segregation in Hartford area schools.

By 1954, defendants were well aware of the growing

pattern of racial segregation in education and its alleged harm

to black children. Between 1954 and the present, defendants

approved and funded the construction of over ninety new schools

in virtually all-white suburban communities, representing over

50% of the total school enrollment in the region. [Source: H.C.

Planning Associates Survey and local reports] During the same

time period, defendants financed a major expansion of school

capacity within the increasingly racially isolated Hartford

school district.

wt 10

e. The state's adoption and im lementation of the "Racial

Imbalance” law and regulations has contributed to and

authorized racial segregation in Hartford schools.

1. Public Act 173, "An Act Concerning Racial Imbalance

in the Public Schools” codified as §10-226a-e was passed in July

1969, requiring “racial balance” among schools within individual

districts. The state adopted the intra-district racial imbalance

law with knowledge that segregation was increasingly an inter-

district phenomenon. As the minutes of a meeting of the

Legislative Committee on Human Rights and Opportunities on

December 5, 1969 reflect, by 1969 it was well established that it

was no longer possible to remedy the problem of racially and

economically segregated schools by desegregating or balancing

city schools, where minorities were already in the majority. To

mandate only intra-district desegregation was to get the suburbs

off "scot free.” (at 1). By 1969, the state was aware of the

multiple reports, including those that gave rise to Project

Concern in 1966, that concluded that racial and economic

isolation was an inter-district problem that demanded an inter-

district remedy. The state was well aware that solutions

restricted by town boundaries would only burden urban areas and

plague them with further racial polarization.

2. The State Board of Education’s delay, from 1969

until 1980, in the adoption of regulations to implement the state

racial imbalance law required by C.G.S. §226e foreseeably

“il -

contributed to racial and ethnic segregation of the schools. In

September, 1969, racial imbalance regulations were prepared and

presented to the State Board of Education. School districts were

notified and the State Board declared its intent to adopt the

regulations. At a time when urban areas were racially polarized,

these actions also notified non-minorities living in the city of

Hartford that desegregation of their schools was imminent. By

delaying the adoption of the controversial regulations, the

state’s white citizens were given ample time to find alternative

arrangements for the schooling of their children.

Although time was of the essence and the racial

composition of city schools were rapidly changing, in March, 1970

after public hearings held in Hartford, the proposed regulations

were rejected. From 1971 to 1975 nothing was done to correct the

problem. Not until 1976 were efforts even renewed to draft

regulations in compliance with the mandate of §10-226.

In May, 1977, the State Board of Education adopted a

Policy and Guidelines for the development of requlations, in

accordance with the Board's stated belief that segregated schools

could not provide truly equitable learning opportunities.

Defendants had knowledge of both the inter-district nature of

segregation in the Hartford area and the continuing fast pace of

change in the racial composition of schools in the city of

Hartford. Nevertheless, no regulations were adopted in 1977.

- 10

Significantly, the ethnic distribution of the

student population changed markedly during the state's delay.

From 1970 to 1980, the white student population in city schools

decreased dramatically, while the non-white population increased.

While the trend toward increasing racial isolation within the

city of Hartford had been clear in 1969, the concept of an intra-

district remedy had quickly become irrelevant.

3. In April, 1980, more than ten years after the

passage of the racial imbalance law and long after school

desegregation within the city of Hartford might have had meaning,

the state prepared and adopted racial imbalance regulations. The

regulations established that a school was “imbalanced” if its

minority enrollment was more that 25 percentage points above or

‘below the district-wide proportion of minority students in that

grade range.

As the State has itself reported, “the statute and

regulations have always placed a heavy burden on those school

districts having large minority student enrollments.” State

Department of Education, “A Report Providing Background

Information Concerning the Chronology and Status of Statutes,

Regulations and Processes Regarding Racial Imbalance in

Connecticut Schools” (January, 1984), at 1. Not only did the

passage of the racial imbalance law and delay in promulgation of

its regulations contribute to racial, ethnic, and economic

v 313 -

-segregation in the Hartford metropolitan area, but enforcement of

the racial imbalance law, with its punitive measures for racial

imbalance, places an undue and unfair burden on Hartford and

other urban school districts with high proportions of African

American and Latino students, while releasing suburban districts

from their responsibility to ensure equity and racial balance.

In addition, as the State further reported in 1984, "as the

overall percentage of minority students in the three largest

cities continues to grow, the concepts on which the statute is

predicated become questionable.” Id.

Hartford was one of the seven urban districts found

by the State Board of Education in 1979 to be in violation of the

racial imbalance law. In March, 1981, the Equal Education and

Racial Balance Task Force, established by the Hartford Board of

Education to assist in the development of a plan to comply with

the new law, not only arrived at a plan but also recommended

changes in the racial imbalance law and regulations to make them

applicable and workable in the City of Hartford. In April, 1981,

Hartford's plan to correct racial imbalance within the school

district was approved by the State Board of Education. In June,

1981, over eleven years after the passage of the racial imbalance

law, defendants began to monitor the Hartford schools for

compliance with the law. In 1988, the State Department again

notified the Hartford schools that Kennelly and Naylor, with

minority enrollments of 38.2% and 32.9% respectively, were, by

definition, racially imbalanced, since they were more than 25

percentage points below the city-wide average of 90.5%. Yet, as

the Hartford public schools stated in its “Alternate Proposal to

Address Racial Imbalance,” "[i]t is clear that the establish ed

definition of racial balance is meaningless for the city of

Hartford. As long as the boundaries of the attendance district

of the Hartford schools is coterminous With he boundaries of the

city, no meaningful numerical balance can be achieved, and it

would be an exercise in futility to develop proposals to seek

racial balance.” “Alternate Proposal,” (1988) at 6. (The

Alternate Proposal was approved by the state.)

f. The state has further contributed to segregation bv

authorizing and/or requiring payment of transportation

costs by local districts for students attending private

schools, and by reimbursing local districts for said

costs,

1. Pursuant to C.G.S. §10-281, the state requires

school districts to provide transportation to

private nonprofit schools and provides reimbursement

for expenses incurred by the district in providing

this transportation.

Pursuant C.G.S. §10-281, the state requires school

districts to provide transportation to a private nonprofit school

in the district whenever a majority of the students attending the

private school are residents of Connecticut and provides for the

reimbursement of expenses incurred by districts providing this

transportation. Plaintiffs intend to produce evidence that the

-_15

implementation of this law by defendants caused and contributed

to increased racial, ethnic, and economic concentration in the

Hartford metropolitan area, in violation of the Connecticut

Constitution.

Since 1971, the state has required districts to

provide transportation to private schools when a majority of

students live in the district. P.A. 653 §§1,2. Defendants have

implemented and enforced this statute with direct knowledge of

its segregative effect. In 1971, the relative percentages of

African American and Latino group enrollment in the public and

non-public schools in the Hartford area were enormously

different. In essence, defendants not only supported a private

school system that, through its admissions policies, effectively

excluded the poor, but also subsidized the transfer of white

school children out of the public school system and into these

private schools at the same time that intra-district

desegregation of the public schools was planned.

In 1974, the state expanded the mandate of §10-281,

requiring districts to provide transportation for students at

private schools when a majority of students attending the schools

are from Connecticut, versus from the particular district. P.A.

74-257 §1. Defendants implemented this expansion, thereby

subsidizing the transfer of white students out of the Hartford

public schools, with a full awareness of its discriminatory

= 16 =

yn effect. Defendants continue to require and subsidize the

transportation of students to non-public schools in the Hartford

metropolitan area.

2. Pursuant to §10-280a, the state permits school

districts to provide transportation to private

nonprofit schools in other districts and, between

1978 and 1989, provided reimbursement for expenses

incurred for transportation to contiguous districts

within Connecticut.

From 1978 through 1989, pursuant to §10-280a, the

state also reimbursed school districts in the Hartford area for

transportation of students to private schools in contiguous

Connecticut districts, thus facilitating the attendance of a

predominantly white, relatively well-off group of students at

non-public schools. The state adopted §10-280a in 1978 with

knowledge of the problem of segregation in Connecticut’s urban

areas and awareness of the damage to be incurred to the

desegregation process by the flight of these schoolchildren to

private schools. See e.g., 21 S. Proc., Pt. 5, 1978 Sess., pp.

1916 (Sen Hudson).

g. The state contributed to racial and economic

segregation, and unequal, inadequate educational

conditions by establishing and maintaining an unequal

and unconstitutional system of educational financing.

Until 1979 the principal source of school funding came

from local property taxes, which depended on the wealth of the

town. This principal source was supplemented by the state by a

$250 flat grant principal, which applied to the poorest and the

-'l7 -

wealthiest towns. There was great wealth disparity which was

reflected in widely varying funds available for local education

I and consequently widely varying quality of education among towns.

The property-rich towns through higher per pupil expenditures

were able to provide a substantially wider range and higher

quality of education services than property-poor towns even as

taxpayers in those towns were paying higher taxes than taxpayers

in property-rich towns. All this was happening even though the

state had the non-delegable responsibility to insure the students

throughout the state received a substantially equal educational

opportunity. Thus prior to 1979, the system of funding public

education in the state violated the state constitution.

In 1979, the state adopted a guaranteed tax base to

rectify in part the finanding inequities. Subsequent delays

between 1980 and 1985 in implementing the 1979 act and the

unjustified use of obsolete data made the formula more

disequalizing and exacerbated disparities in per pupil

expenditures. These conditions denied students their rights to

substantially equal educational opportunities under the state

constitution. [Sources for this section include Horton v.

Meskill, 31 Conn. Sup. 377, 332 A.2d 113 (1874): l1d., 172 Conn.

615, 376 A.2d 359 (1977); Supreme Court Record in previous case,

(No. B127); Horton v. Meskill, 195 Conn. 24, 486 A.2d 1099

(1985); Supreme Court Record in previous case, Nos. 12499-12502)

-i3 -

h. The state has contributed to racial and economic

segregation in housing.

Plaintiffs are not claiming in this lawsuit that any of

the state's housing actions are unconstitutional. Any such

claims are expressly reserved. However, the state has played an

important causal role in the process of residential segregation

in the Hartford region, and plaintiffs will describe, through

expert testimony, some of the ways that the state of Connecticut

has contributed to segregated housing patterns. Plaintiffs’

testimony on these issues may include but will not be limited to

the following areas:

Location of Assisted Housing: At least 73% of

Hartford-area subsidized family housing units are located in the

City of Hartford. The state has played a direct role in the

creation, funding, approval, siting, or administration of many of

these units over the past 40 years.

Transportation: During the same time period, the

state has engaged in a series of transportation decisions that

have increased “white flight” from Hartford, limited minority

access to employment opportunities, and exacerbated racial and

economic residential segregation in the Hartford region.

Affirmative Marketing: In its administration of

state housing programs, the state has failed to monitor and

enforce affirmative marketing plans for state-funded suburban

housing developments, including, on information and belief,

- 10 ie

failure to require affirmative marketing during initial

occupancy, failure to provide adequate numbers of staff to

monitor and enforce affirmative marketing requirements, failure

to conduct surveys of racial occupancy, and failure to require

affirmative marketing plans until 1988.

Statutory Barriers: The state has provided suburban

towns with veto power over state-subsidized projects through

C.G.S. §8-120, which prohibits the Connecticut Housing Authority

from developing new housing, including Section 8 developments, in

any municipality without a finding of need or approval by the

local governing body of the municipality, and through C.G.S. §§8-

39(a) and 8-40, which prohibit local housing authorities from

constructing, rehabilitating or financing a housing development

in a neighboring municipality without that municipality's

permission.

Rental Assistance: Another way in which the state

has contributed to residential segregation through its

administration of state housing programs is through its

administration and oversight of state and federal rental

assistance programs, and its failure to permit or encourage such

certificates to be used in a portable manner to permit

certificate holders to cross municipal lines.

Residency Preferences: The state has officially

permitted the use of residency preferences by suburban public

housing authorities, including certain PHAs in the Hartford area.

Residency preferences have a discriminatory impact in white

suburban communities, limiting the access of low income minority

residents to suburban housing opportunities and suburban schools.

Exclusionary Zoning: The state has been repeatedly

advised of the discriminatory and exclusionary effects of its

system of planning, zoning and land use laws and regulations,

which have permitted local governments to erect zoning and other

land use barriers to the construction of multifamily housing,

rental housing, manufactured housing, and subsidized low and

moderate income housing.

* * * * *

At the present time, plaintiffs are continuing to

investigate actions taken by defendants that have contributed to

the constitutional violations set out in the Complaint.

Plaintiffs’ investigation is ongoing and is subject to amendment

in a timely fashion. At this time, except as set out above,

plaintiffs have not completed investigation as to what specific

“information [defendants]...had or should have had” at particular

times which would have "apprised defendants of the consequences

of particular actions.” Plaintiffs’ position is that although

proof of such “notice” is not necessary for plaintiffs to

prevail, nonetheless the increasing racial and economic

segregation in area schools was obvious, and numerous reports and

-——y

-gtudies put the state on notice of the problems and possible

causes and solutions. See response to Interrogatory 5. Further

details in response to this interrogatory will be provided in a

timely fashion, in advance of trial.

2. Please identify each and every affirmative act by the

defendants, their predecessors or any other state officer, agency

or other body which the plaintiffs will claim at trial caused the

conditions of racial and ethnic isolation in the Hartford Public

Schools and/or the identified suburban school districts. For

each such act provide the date the act occurred, the person,

agency or other body responsible for the act, and any and all

information the plaintiffs will claim that person, agency or

other body had or should have had at that time which would have

apprised them of the consequences of that act.

RESPONSE: [Please see response to Interrogatory 1]

3. Please identify each and every affirmative act by the

defendants, their predecessors or any other state officer, agency

or other body which the plaintiffs will claim at trial caused the

condition of socio-economic isolation in the Hartford Public

Schools and/or the identified suburban school districts. For

each such act provide the date the act occurred, the person,

agency or other body responsible for the act, and any and all

information the plaintiffs will claim that person, agency or

other body had or should have had at that time which would have

apprised them of the consequences of the act.

RESPONSE: [Please see response to Interrogatory 1]

4. Please identify each and every affirmative act by the

defendants, their predecessors or any other state officer, agency

or other body which the plaintiffs will claim at trial cause the

concentration of "at risk” children in the Hartford Public

Schools. For each such act provide the date the act occurred,

the person, agency or other body responsible for that act, and

any and all information the plaintiffs will claim that person,

agency or other body had or should have had at that time which

would have apprised them of the consequences of that act.

RESPONSE: [Please see response to Interrogatory 1)

i222.

PAST VIOLATIONS: OMISSIONS

so

il

5. Please identify each and every affirmative act, step, or

plan which the plaintiffs will claim at trial the defendants,

| their predecessors, or any other state officer, agency or other

body were required by the State Constitution to take or implement

to address the condition of racial and ethnic isolation in the

Hartford Public Schools and the identified suburban school

districts, but which was not in fact taken or implemented. For

each such act, step, or plan provide the following:

a) The last possible date upon which that act, step or

plan would necessarily have been taken or

implemented in order to have avoided a violation

that the Constitution;

b) The specific details of how such act, step or plan

should have been carried out, including (1) the

specific methods of accomplishing the objectives of

the act, step or plan, (2) an estimate of how long

it would have taken to carry out the act, step, or

plan, and (3) an estimate of the cost of carrying

out the act, step or plan;

c) For Hartford and each of the identified suburban

school districts, the specific number and percentage

of black, Hispanic and white students who would, of

necessity, have attended school outside of the then

existing school district in which they resided in

order for that act, step or plan to successfully

address the requirements of the Constitution.

RESPONSE: As set out in the Complaint, defendants’ failure to

act in the face of defendants’ awareness of the educational

necessity for racial, ethnic, and economic integration in the

public schools, defendants’ recognition of the lasting harm

inflicted on poor and minority students concentrated in urban

school districts, and defendants’ knowledge of the array of legal

tools available to defendants to remedy the problem, is violative

of the State Constitution. Plaintiffs challenge defendants!’

‘4 “failure to provide plaintiffs with the equal educational

- a3.

opportunities to which the defendants were obligated to ensure.

~~ 8ince At least 1965, -when the United ‘States Civil Rights

Commission reported to Connecticut’s Commissioner of Education,

defendants have had knowledge of the increasing racial, ethnic,

and economic segregation in the Hartford metropolitan area and

the power and authority to remedy this school segregation. Not

only did defendants fail to take comprehensive or effective steps

to ameliorate the increasing segregation in and among the

region's schools, but defendants also failed to provide equal

access to educational resources to students in the shoals in the

Hartford metropolitan area. Such resources include, but are not

limited to, number and qualification of staff; facilities;

materials, books, and supplies; and curriculum offerings.

Specifically, plaintiffs may present evidence at trial of

the many reports and recommendations presented to Defendants

which documented the widespread existence of racial, ethnic, and

economic segregation and isolation among the school districts and

which proposed or endorsed remedial efforts to eliminate such

segregation. Plaintiffs will not necessarily claim that if

implemented, the specific programs and policies offered in such

reports and recommendations would have been sufficient to address

the constitutional violation. Neither will plaintiffs

necessarily claim that any one particular recommendation was

- Ol

+ required by the State Constitution. These reports and

| recommendations may include but are not limited to the following:

a. United States Civil Rights Commission, Report to

Connecticut's Commissioner of Education (1965);

b. Center for Field Studies, Harvard Graduate School

of Education, Schools for Hartford (Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University, 1965);

c. "Equality and Quality in the Public Schools,”

Report of a Conference Sponsored Jointly by the

Connecticut Commission on Civil Rights and the

Connecticut State Board of Education,” (1966).

d. Request by the Connecticut Civil Rights Commission

to the Governor (request that the Governor take a

stand against de facto segregation and publish a

statement on the drawbacks of de facto segregation

in the schools) (1966).

e. Committee of Greater Hartford School

Superintendents, Proposal to Establish a

Metropolitan Effort Toward Regional Opportunity

(METRO) (1966);

f. Legislative Commission on Human Rights and

Opportunities, Plan for the Creation and Funding of

Educational Parks (Hartford, December, 1968);

g. Task Force, Regional Advisory Committee for the

Capitol Region, “The Suburbs and the Poverty

Problems of Greater Hartford,” (Hartford, September

30, 1968);

h. Irving L. Allen and J. David Colfax, Urban Problems

and Public Opinion in Four Cities (Urban Research

Report No. 14, Community Structure Series No. 3;

Storrs, Conn.: University of Connecticut, 1968);

i. Walter R. Boland, et al., De Facto School

Segregation and The Student: A Study of the

Schools in Connecticut's Five Major Cities (Urban

Research Report No. 15, Community Structure Series

No. 4; Storrs, Conn.: University of Connecticut,

1968);

- OB

Educational Resources and Development Center, The

School of Education and Continuing Education

Service, University of Connecticut, A Study of

Urban School Needs in the Five Largest Cities of

Connecticut (Storrs, Conn.: University of

Connecticut, 1969);

Edward A. Lehan, Executive Secretary to the

Hartford City Manager, Report on Racial Composition

of Hartford Schools to the State Board of Education

(Hartford, 1969);

Joint Committee of the Hartford Board of Education

and the Human Relations Commission, Hartford,

Report, (July, 1969);

City of Hartford, “Community Development Action

Plan: Education 1871-1975,” (Sept. 1, 1970);

Hartford Board of Education, “Recommended Revision

in School Building Program,” (May 18, 1970);

Local Government: Schools and Property, “The

Report of the Governor's Commission on Tax Reforms,

Submitted to Governor Thomas J. Meskill Pursuant to

Executive Order 13 of 1972,” (Hartford,

Connecticut, December 18, 1972);

Commission to Study School Finance and Equal

Educational Opportunity, Financing Connecticut

Schools: Final Report of the Commission (Hartford,

Conn., January, 1975);

Equal Education and Racial Balance Task Force,

appointed by the Hartford Board of Education,

“Advisory Report,” (Hartford, March, 1981);

Connecticut State Department of Education, “A Report

Providing Background Information Concerning the

Chronology and Status of Statutes, Regulations and

Processes Regarding Racial Imbalance in Connecticut’s

Public Schools,” (February 6, 1986);

Connecticut State Department of Education, “The Issue of

Racial Imbalance and Quality Education in Connecticut's

Public Schools,” (February 5, 1986);

- 00 -

I u. “State Board of Education Policy Statement on Equal

| Educational Opportunity,” Connecticut State Board of

Education, (Hartford, October 27, 1986);

v. "Report on Racial/Ethnic Equity and Desegregation

in Connecticut's Public Schools,” Connecticut

State Department of Education (1988); and

w. "Quality and Integrated Education: Options for

Connecticut,” Connecticut State Department of

Education (1989).

x. Governor's Commission Report 1990.

In addition to the recommendations and reports set out

above, the State failed to adequately supplement the funding of a

known successful integration program, Project Concern, beginning

in 1980 when federal funding cutbacks and Hartford Board of

Education cutbacks forced a reduction in the numbers of children

participating in the program and in the numbers of staff hired to

service these children (e.g. paraprofessionals, resource

teachers, bus stop aides). The State has also failed to take ap-

propriate steps to increase the numbers of children participating

over and above the approximately 730+ students now enrolled in

the program, despite knowledge that receiving school districts

would increase their participation if the State provided funding.

The following studies and documents, among others, have repeated-

ly demonstrated to the Defendants that Project Concern is one of

a number of programs to successfully provide an equal educational

ER oes,

jon t and a meaningful integrated experience for some urban

|| and suburban children:

a. Mahan, Thomas W. The Impact of Schools on Learning:

—— ~~... Inner-City Children in Suburban Schools.

b. Mahan, Thomas W. Project Concern 1966-1968, A Report on

the Effectiveness of Suburban School Placement for

Inner-City Youth (1968).

c. Ninety-First Congress, Second Session on Equal Education

Opportunity. “Hearing Before the Select Committee on

Equal Educational Opportunity of the United States

Senate.” 1970.

d. Connecticut State Department of Education, “Reaction to

Racial Imbalance Guidelines for Hartford Public

Schools.” April 20, 1870.

e. State Board of Education Minutes (Capital Region

Planning Agency Endorses the Expansion of Project

Concern) January 7, 1970.

f. Gable, R. and Iwanicki, E., A Synthesis of the

Evaluation Findings from 1976-1980 (May 1981)

g. Gable, Thompson, Iwanicki, The Effects of Voluntary

Desegregation on Occupational Outcomes, The Vocational

Guidance Quarterly 31, 230-239 (1983)

h. Gable, R.and Iwanicki, E. The Longitudinal Effects of a

Voluntary School Desegregation Program on the Basic

Skill Progress of Participants. 1 Metropolitan

Education 65. Spring, 1986.

i. Gable, R. and Iwanicki, E., Project Concern Evaluation.

October, 1986.

Jj. Gable, R. and Iwanicki, E., Final Evaluation Report

| 1986-87 Hartford Project Concern Program (December

1987)

k. Gable, R. and Iwanicki, E., Final Evaluation Report

1988-89: Hartford Project Concern Program (Nov. 1989)

28

l. Crain, R., et al., Finding Niches: Desegregated

Students Sixteen Years Later, Rand Reports, (1985);

revised 1990

m. Crain, R., et al., School Desegregation and Black

Occupational Attainment: Results from a Long Term

Experiment; (1985).

n. “Project Concern Enrollment 1966-1990,” (Defs’ Response

to Plaintiffs’ First Request for Production, 13(b)).

o. Iwanicki, E., and Gable, R., Almost Twenty-Five Years of

Project Concern: An Overview of the Program and Its

Accomplishments, (1990) (and sources cited therein)

(Defs' Response to Plaintiffs’ First Request for

Production, 12 (g).

In addition, Plaintiffs’ evidence at trial may include

but will not be limited to testimony and reports demonstrating

defendants’ failure to eliminate exclusionary zoning and housing

policies; defendants’ failure to promote integrated housing in

the Hartford region; and defendants’ failure to establish a

constitutional system of educational financing (see response to

Interrogatory 1).

In regard to questions 5 a, b, and c, as set out in

Defendants’ Interrogatory 5, Plaintiffs have not determined and

are, at least at this time, unable to estimate the “last possible

date” upon which individual actions, steps, or plans would

necessarily have had to have been implemented in order to have

avoided violation of the State Constitution, nor do plaintiffs

concede the relevance of such an inquiry. Likewise, plaintiffs

are not required to specify which methods would have cured the

constitutional violation at particular moments in time, how long

]

- 230 .

“such methods would have taken to implement, or the cost of

implementation. Such questions, including the number and

percentage of African American, Latino, and white students who

may seek to attend school outside of the boundaries of the city

of Hartford, are issues which plaintiffs expect would be

addressed by plaintiffs’ expert witnesses on desegregation

remedies after a determination is made by the court as-to the

state's liability.

6. Please identify each and every affirmative act, step or

plan which the plaintiffs will claim at trial the defendants,

their predecessors, or any other state officer, agency or other

body were required by the State Constitution to take or! implement

to address the condition of socio-economic isolation in ithe

Hartford Public Schools and the identified suburban school

districts, but which was not in fact taken or implemented. For

each such act, step or plan provide the following:

a) The last possible date upon which that act, step or

plan would necessarily have been taken or

implemented in order to have avoided a violation of

the Constitution; :

b) The specific details of how such act, step or plan

should have been carried out including, (1) the

specific methods of accomplishing the objectives of

the act, step or plan, (2) an estimate of how long

it would have taken to carry out the act, step or

plan, and (3) an estimate of the cost of carrying

out the act, step or plan;

c) For Hartford and each of the identified suburban

school districts, the specific number and percentage

of poor, middle, and/or upper class students who

would, of necessity, have attended school outside of

the then existing school district in which they

resided in order for that act, step, or plan to

successfully address the requirements of the

Constitution;

-30 «

d) The specific criteria which should have been used to

identify those students who would, of necessity,

have attended school outside the then existing

school district in which they resided, so that the

concentration of students from poor families in

Hartford Public Schools would be low enough to

satisfy the requirements of the Constitution.

RESPONSE: Please see response to Interrogatory 5. Plaintiffs

have not, at this point, alleged that one specific criterion or

indicator must be used to identify students who “would, of

necessity” be transferred to another school district. As stated

in the Complaint, rates of family participation in the federal

Aid to Families with Dependent Children program is widely

accepted as a measure closely correlated with family poverty.

Participation in the federal school lunch program is also an

‘index of poverty status.

7. Please identify each and every affirmative act, step or

plan which the plaintiffs will claim at trial the defendants,

their predecessors, or any other state officer, agency or other

body were required by the State Constitution to take or implement

to address the conditions created by the concentration of “at

risk” children in the Hartford Public Schools but which were not

in fact taken or implemented. For each such act, step, or plan

provide the following:

a) The last possible date upon which that act, step or

plan would necessarily have been taken or

implemented in order to have avoided a violation of

the constitution; :

b) The specific details of how such act, step or plan

should have been carried out including (1) the

specific methods of accomplishing the objective of

the act, step or plan, (2) an estimate as to how

long it would have taken to carry out the act, step

or plan, and (3) an estimate of the cost of carrying

out the act, step or plan;

9

—

@® a IE THERESE: Na We - RP -n a — - aa er ne

- 3] =~

c) The specific number and percentage of “at risk”

Hartford students who would, of necessity, have

attended school outside of the existing school

district in which they resided in order for that

act, step or plan to successfully address the

requirements of the Constitution.

d) The specific criteria which should have been used to

identify those students who would, of necessity,

have attended school outside the then existing

school district in which they resided so that the

concentration of “at risk” students in Hartford

Public Schools would be low enough to satisfy the

requirements of the Constitution.

RESPONSE: Please see response to Interrogatory 5. As set out in

the Complaint in this action, all children, including those

deemed at risk of lower educational achievement, have the

capacity to learn if given a suitable education. Yet, the

Hartford public schools operate at a severe educational

disadvantage in addressing the educational needs of all students,

due in part to the sheer proportion of students who bear the

burdens and challenges of living in poverty. The increased need

for special programs, such as compensatory education, stretches

Hartford school resources even further. As also stated in the

Complaint, the demographic characteristics of the students in the

Hartford public schools differ sharply from students in the

suburban schools by a number of relevant measures, such as

poverty status, whether a child has limited English proficiency,

and whether a child is from a single-parent family. Plaintiffs

have not, at this point, alleged that one specific criterion or

“indicator must be used to identify students who “would, of

necessity” be transferred to another school district.

CURRENT OR ONGOING VIOLATIONS

8. Using the 1987-88 data as a base, for Hartford and each

of the identified suburban school districts please specify the

number and percentage of black, Hispanic and white students who

must, of a necessity, attend school in a location outside of the

existing school district in which they reside in order to address

the condition of racial and ethnic isolation which now exists in

accordance with the requirements of the Constitution.

RESPONSE: Objection [Please see plaintiffs’ objection to

Interrogatory 8, Plaintiffs’ Objections To Interrogatories, Filed

September 20, 1990, attached hereto. ]

9. Using the 1987-88 data as a base, for Hartford and each

of the identified suburban school districts please specify the

number and percentage of poor, middle and/or upper class students

who must, of necessity, attend school outside of the existing

school district in which they reside in order to address the

condition of socio-economic isolation which exists in Hartford

and the identified suburban school districts in accordance with

the requirements of the Constitution. Also identify the specific

criteria which must be used to identify the pool of poor Hartford

students from which those students who would be required to

attend schools outside of the existing district in which they

reside must be chosen so as to address the condition of socio-

economic isolation in accordance with the requirements of the

Constitution.

RESPONSE: Objection [Please see plaintiffs!’ objection to

Interrogatory 9, Plaintiffs’ Objections To Interrogatories, Filed

September 20, 1990, attached hereto. ]

“33

10. Using the 1987-88 data as a base, identify the number

and percentage of "at risk” children in the Hartford Public

Schools who must, of necessity, attend school at a location

outside the existing Hartford School District lines in order to

address the concentration of “at risk” children in the Hartford

Public Schools in accordance with the requirements of the

Constitution. Also identify the specific criteria which must be

used to identify the pool of Hartford students from which those

who would be required to attend schools in the suburban school

districts must be chosen so as to address the concentration of

“at risk” children in the Hartford Public Schools.

‘RESPONSE: Objection [Please see plaintiffs’ objection to

Interrogatory 10, Plaintiffs’ Objections To Interrogatories,

Filed September 20, 1990, attached hereto. ]

MINIMALLY ADEQUATE EDUCATION

11. Please identify each and every statistic the

plaintiffs’ will rely on at trial to support any claim they

intend to make that the educational “inputs” (i.e. resources,

staff, facilities, curriculum, etc:) in the Hartford Public

Schools are so deficient that the children in Hartford are being

denied a “minimally adequate education.” For each such fact

specify the source(s) and/or name and address of the person(s)

that will be called upon to attest to that statistic at trial.

RESPONSE: [Please see response to Interrogatory 13.]

12. Please identify each and every statistic, other than the

results of the Mastery Test, which the plaintiffs will rely on at

trial to support any claim they intend to make that children in

Hartford are being denied a “minimally adequate education”

because of the educational “outputs” for Hartford. For each such

fact specify the source(s) and/or name and address of the

person(s) that will be called upon to attest to that statistic at

trial.

RESPONSE: [Please see response to Interrogatory 14.]

- 34 0.

EQUAL, EDUCATION

13. Please identify each and every category of educational

“inputs” which the plaintiffs will rely on at trial in their

effort to establish that the educational “inputs” in Hartford are

not equal to the educational “inputs” of the suburban school

districts. For each such category identify each and every

statistical comparison between Hartford and any or all of the

suburban school districts which the plaintiffs will rely on to

show the alleged inequality. For each such comparison identify

the source(s) and/or name and address of the person(s) that will

be called upon to attest to the accuracy of that statistical

comparison at trial.

RESPONSE: As of the date of this response, plaintiffs are

compiling data and information on disparities and inequities in

“educational inputs” and resources among Hartford and the

surrounding districts. This data may include, but may not be

limited to comparisons in the following areas:

a. Facilities -- data may include, but may not be

limited to comparisons of the condition and size of

school buildings, the condition and size of school

grounds, overcrowding and school capacity,

maintenance, the availability of specific

instructional facilities and physical education

facilities, and special function areas (e.g. types

of counselling, libraries);

b. Equipment and Supplies;

Cc. Personnel -- data may include, but may not be

limited to comparisons of student teacher ratios,

teaching staff characteristics, and non-teacher

staff number and characteristics;

d. Curriculum -- data may include, but may not be

limited to comparisons of course offerings,

textbooks and course levels, and special programs;

€. Extracurricular Opportunities; and

p

p

- 35

f. School evperience -- data may include, but may not

be limited to comparisons of counselling services,

disciplinary rates, absentee rates, retention

rates, tardy rates, and the concentration of -

poverty.

At the present time, plaintiffs’ investigation and analysis

of these categories has not been completed. The data and

information concerning disparity in “inputs” upon which

plaintiffs rely is equally available to defendants.

Nevertheless, plaintiffs will disclose such information in a

timely manner prior to trial.

14. Please identify each and every category of educational

“outputs” other than the Mastery Test, which the plaintiffs will

rely on at trial in their effort to establish that the

educational “outputs” in Hartford are not equal to the

educational “outputs” of the suburban school districts. For each

such category identify each and every statistical comparison

between Hartford and any one or all of the suburban school

districts which the plaintiffs will rely on to show the alleged

inequality. For each such comparison identify the source(s)

and/or name and address of the person(s) that will be called upon

to attest to the accuracy of that statistical comparison at

trial,

RESPONSE: As listed in plaintiffs’ response to Interrogatory 18,

Professor Robert Crain is expected to testify to the following

areas of comparison: the likelihood of (1) dropping out of high

school; (2) early teenage pregnancy; (3) unfavorable interactions

with the police; (4) college retention; (5) working in private

sector professional and managerial jobs; (6) interracial contact,

occupationally and otherwise; and (7) favorable interracial

attitudes. Plaintiffs are also compiling data and information on

- 36 -

disparities and inequities in other measures of achievement or

educational quality among Hartford and the surrounding districts,

including but not limited to percentage of students receiving a

diploma; PSAT and SAT scores; enplovient cutoones; and career and

life outcomes. At the present time, plaintiffs’ investigation

and analysis of these and other categories have not been

completed. Plaintiffs have not yet identified who will present

analyses of such data at trial, other than those experts listed

in plaintiffs’ response to Interrogatories 18 and 19. Plaintiffs

will disclose such information in a timely manner prior ito trial.

OTHER

15. Please identify each and every study, other document,

or information or person the plaintiffs will rely upon or call

upon at trial to support the claim that better integration will

improve the performance of urban black, Hispanic and/or socio-

economically disadvantaged children on standardized tests such as

the Mastery Test.

RESPONSE: As set out in the complaint, racial and economic

isolation in the schools adversely affects both educational

attainment and the life chances of children. The studies,

decinenite, information, and persons upon whom the plaintiffs will

rely at trial may include, but are not limited to information

listed in the response to Interrogatory 19 and the following:

Crain, R.L., and Braddock, J.H., McPartland, JM., "A

Long Term View of School Desegregation: Some Recent

Studies of Graduates as Adults,” 66 Phi Delta Kappan

259-264 (1984);

J!

p

e

r

v

de

nt

- 37 -

Crain, R.L., and Hawes, J.A., Miller, R.L., Peichert,

J.R., "Finding Niches: Desegregated Students Sixteen

Years Later,” R-3243-NIE, Rand (January, 1985);

Crain, R.L., and Strauss, J., “School Desegregation and

Black Occupational Attainments: Results from a Long-

term Experiment,” Reprinted from CSOS Report No. 359

(1985);

Levine, D.U., Keeny, J., Kukuk, C., O'Hara Fort, B.,

Mares, K.R., Stephenson, R.S., “Concentrated Poverty

and Reading Achievement in Seven Big Cities,” 11 Urban

Review 63 (1979).

“Poverty, Achievement and the Distribution of

Compensatory Education Services,” National Assessment

of Chapter 1, Office of Educational Research and

Improvement, U.S. Dept. of Ed. (1986);

"Report on Negative Factors Affecting the Learning

Process," Hartford Board of Education (1987);

Connecticut State Department of Education (various

reports, past and present, including but not limited to

reports on racial, ethnic, and economic segregation,

racial balance, school resources, and educational

outcomes).

See also reports listed in Plaintiffs’ Identification of

Expert Witnesses Pursuant to Practice Book §220 (D) (January

15, 1991), attached hereto.

16. Please identify each and every study, other document,

or information or person the plaintiffs will rely upon or call

upon at trial to support the claim that better integration will

improve the performance of urban black, Hispanic and/or socio-

economically disadvantaged children on any basis other than

standardized tests.

RESPONSE: [Please see response to Interrogatory 15.]

17. Please describe the precise mathematical formula used

by the plaintiiis to compute the ratios set forth in paragraph 42

of the complaint.

RESPONSE: Plaintiffs recognize that the computation set out in

942 of the Complaint may be inaccurate. Plaintiffs have

indicated their willingness to discuss stipulation as to

aggregate city vs. suburban mastery test scores.

EXPERT WITNESSES

18. Please specify the name and address of each and every

person the plaintiffs expect to call as an expert witness at

trial. For each such person please provide the following:

a) The date on which that person is expected to

complete the review, analysis, or consideration

necessary to formulate the opinions which that

person will be called upon to offer at trial;

The subject matter upon which that person is

expected to testify; and

The substance of the facts and opinions to which

that person is expected to testify and a summary of

the grounds for each opinion.

RESPONSE: On January 15, 1991, the plaintiffs disclosed their

initial list of expert witnesses anticipated to testify at trial,

pursuant to Practice Book §220 (D), as modified by this Court's

Order of October 31, 1990 and the parties’ Joint Motion for

Extension of Time to Disclose Expert Witnesses filed December 3,

1990. See Plaintiffs’ Identification of Expert Witnesses

Pursuant to Practice Book §220 (D) (January 15, 1991); attached

hereto and incorporated herein by reference. In addition,

- 35

plaintiffs have identified other possible witnesses who may

testify at the trial in this action, but whose analyses are not

sufficiently complete to respond to defendants’ interrogatory or

to confirm whether plaintiffs expect to call such witnesses.

Additional expert witnesses will be identified as set out in the

parties’ December 3, 1990 Joint Motion, as they become available.

DATA COMPILATIONS

19. In the event the plaintiffs intend to offer into

evidence at trial any data compilations or analyses which have

been produced by the plaintiffs or on the plaintiffs’ behalf by

any mechanical or electronic means please describe the nature and

results of each such compilation and/or analysis and provide the

following additional information.

a)

b)

c)

e)

£)

g)

The specific kind of hardware used to produce each

compilation and/or analysis;

The specific software package or programming

language which was used to produce each compilation

and/or analysis;

A complete list of all specific data elements used

to produce each compilation and/or analysis;

The specific methods of analyses and/or questions

used to create the data base for each compilation

and/or analysis;

A complete list of the specific questions, tests,

measures, or other means of analysis applied to the

data base to produce each compilation and/or

analysis;

Any and all other information the defendants would

need to duplicate the compilation or analysis;

The name, address, educational background and role

of each and every person who participated in the

development of the data base and/or program used to

i 0:

analyze the data for each compilation and/or

analvsin: and

h) The name and address of each and every person

-expected to testify at trial who examined the

results of the compilation or analysis and who

~reached any conclusions in whole or in part from

those results regarding the defendants’ compliance

with the law, and, for each such person, provide a

complete list of the conclusions that person

reached.

RESPONSE: Plaintiffs may offer into evidence compilations and

analyses including but not limited to analyses of data on the

educational and long-term effects of racial, ethnic, and economic

segregation. In addition, plaintiffs may offer into evidence

compilations and analyses on other elements of plaintiffs’ case,

including the disparity in resources between Hartford and the

suburban schools. Plaintiffs are still compiling and analyzing

data drawn from the following sources and will provide more

detailed information in such research when it is available. Such

information will be provided in a timely fashion, in advance of

trial,

The data sets which form the basis for the analyses of the

educational and long-term effects of racial, ethnic, and economic

segregation include, but will not be limited to the following:

(1) The National Longitudinal Survey of Labor Force

Behavior -- Youth Cohort, an annual survey

sponsored by the U.S. Departments of Labor and

Defense of 12,686 young persons throughout the

United States. Data available and used in this

research begins in 1979 and extends through 1987.

|

(2)

(3)

(4)

- dy -

The National Survey of Black Americans, a national

survey oi 22,1927 African Americans who are 18 years

of age or older. The survey was designed and

conducted by the survey Research Center, Institute

for Social Research at the University of Michigan.

Data was collected between 1979 and 1980.

The High School and Beyond Study, a national

longitudinal probability sample of more than 58,000

1980 high school sophomores and seniors. Surveys

were conducted in 1980, 1982, 1984, and 1986.

The National Longitudinal Survey of Employers, a

national probability sample of 4,087 employers.

Surveys were conducted in the 1970's.

Further sources of data are set out in Plaintiffs’

Identification of Expert Witnesses Pursuant to Practice Book §220

(D), served on January 15, 1991, and incorporated herein by

reference.

With respect to defendants’ questions a-d, at this time,

plaintiffs’ counsel are aware that some experts conducted

regression analyses using SPSS software on IBM computers.

this, plaintiffs are currently unable to specify the kind of

hardware used to produce each analysis, the specific software

package used,

and specific methods of analysis.

information in a timely fashion as it becomes available to the

plaintiffs, in advance of trial.

Beyond

the complete list of specific data elements used;

Plaintiffs will provide such

- 42 -

MISCELLANEOUS

20. For each of the above listed interrogatories please

provide the names and address of each person who assisted in the

preparation of the answer to that interrogatory and describe the

nature of the assistance which that person provided.

RESPONSE: Objection. [See plaintiffs’ Objection to

Interrogatory 20, Plaintiffs’ Objections to Interrogatories,

Filed September 20, 1990.] Without waiving their objection,

plaintiffs respond that the responses to the foregoing

interrogatories were prepared by counsel in consultation with

experts identified in Plaintiffs’ Identification of Expert

Witnesses Pursuant to Practice Book §220 (D), served on January

15, 1991, as well as additional exvaTts to be identified pursuant

to the parties’ Joint Motion for Extension of Time to Disclose

"Expert Witnesses filed December 3, 1990.

PLAINTIFFS, MILO SHEFF, ET AL

HAVE LAF or A774

MARIANNE ENGELMAN LADO

RONALD ELLIS

"NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Pro Hac Vice

MARTHA STONE

CONNECTICUT CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION FOUNDATION

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 0 06106

(203) 247-9823

Juris No. 61506

WILFRED RODRIGUEZ

HISPANIC ADVOCACY PROJECT

Neighborhood Legal Services

1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, CT 06102

(203) 278-6850

Juris No. 302827

ADAM S. COHEN

HELEN HERSHKOFF

JOHN A. POWELL

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION FOUNDATION

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

Pro Hac Vice

PHILIP D. TEGELER

CONNECTICUT CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION FOUNDATION

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

(203) 247-9823

Juris No. 102537

WESLEY W. HORTON

MOLLER, HORTON &

FINEBERG, P.C.

90 Gillett Street

Hartford, CT 06105

(203) 522-8338

Juris No. 38478

JOHN BRITTAIN

UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT

SCHOOL OF LAW

65 Elizabeth Street

Hartford, CT 06105

(203) 241-4664

Juris No. 101153

JENNY RIVERA

PUERTO RICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-3360

Pro Hac Vice

Cv89-0360977S

SUPERICACUURT

Plaintiffs

v. JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al. AT HARTFORD

Defendants JANUARY 15, 1991

00

00

e0

80

00

d8

eo

00

00

eo

PLAINTIFFS’ IDENTIFICATION OF EXPERT WITNESSES

PURSUANT TO PRACTICE BOOK §220 (D)

Pursuant to Practice Book §220(D), as modified by this

Court's Order of October 31, 1990 and the parties’ Joint Motion

for Extension of Time to Disclose Expert Witnesses filed December

3, 1990, the plaintiffs herein disclose their initial list of

expert witnesses anticipated to testify at trial, in response to

Defendants’ First Set of Interrogatories. In addition,

plaintiffs have identified other possible witnesses who may

testify at the trial in this action, but whose analyses are not

sufficiently complete to respond to defendants’ interrogatory or

to confirm whether plaintiffs expect to call such witnesses. As

set out in the parties’ Joint Motion for Extension of Time to

Disclose Expert Witnesses filed December 3, 1990, such additional

expert witnesses may be identified in sixty days or thereafter.

Interrogatory 18. Please specify the name and address of

each and every person the plaintiffs expect to call as an expert

witness at trial. For each such person please provide the

following:

a. The date on which that person is expected to complete

the review, analysis, or consideration necessary to formulate the

opinions which that person will be called upon to offer at trial;

b. The subject matter upon which that person is expected to

testify; and

Cc. The substance of the facts and opinions to which that

person is expected to testify and a summary of the grounds for

each opinion.

RESPONSE: Experts whom the plaintiffs expect to call at trial

are listed below, pursuant to Practice Book Section 220(D), as

modified by the Court:

Dr. Jomills Henry Braddock, II, Center for Social

Organization of Schools, Johns Hopkins University, 3505

North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21218. Dr.

Braddock is expected to testify to (1) the adverse

educational and long-term effects of racial, ethnic,

and economic segregation; (2) the adverse effects of

racial, ethnic, and economic segregation on the

educational process within schools. Specifically, Dr.

Braddock is expected to testify that school segregation

tends to perpetuate segregation in adult life, that

school desegregation helps to transcend systemic

reinforcement of inequality of opportunity, and that

segregation affects the educational process within

schools. In his testimony, the materials on which Dr.

Braddock is expected to rely include his published

works, as well as research currently being conducted on

the educational and long-term effects of racial,

ethnic, and economic segregation by Dr. Marvin P.

i 3.

Dawkins and Dr. William Trent. (See descriptions

below.) Dr. Braddock is expected to base his testimony

on (1) Braddock, “The Perpetuation of Segregation

Across Levels of Education: A Behavioral Assessment of

the Contact-Hypothesis,” 53 Sociology of Education 178-

186 (1980); (2) Braddock, Crain, McPartland, “A Long-

Term View of School Desegregation: Some Recent Studies

of Graduates as Adults.” Phi Delta Kappan 259-264

(1984); (3) Braddock, “Segregated High School

Experiences and Black Students’ College and Major Field.

Choices,” Paper Presented at the National Conference on

School Desegregation, University of Chicago (1987); (4)

Braddock, McPartland, “How Minorities Continue to be

Excluded from Equal Employment Opportunities: Research

on Labor Market and Institutional Barriers,” 43 Journal

of Social Issues 5-39 (1987); and (5) Braddock,

McPartland, “Social-Psychological Processes that

Perpetuate Racial Segregation:. The Relationship

Between School and Employment Desegregation,” 19

Journal of Black Studies 267-289 (1989). Dr. Braddock

is expected to complete his review by April 1, 1991.

Christopher Collier, Connecticut State Historian, 876

Orange Center Road, Orange, Connecticut, 06477.

Professor Collier is expected to testify regarding (1)

the historical lack of autonomy of Connecticut towns

and school districts and the history of state control

over local education; (2) the historical development of

the system of town-by-town school districts including

legislation passed in 1856, 1866, and 1909; (3) the

existence and prevalence of school districts and

student attendance patterns crossing town lines prior

to 1903 legislation mandating consolidation; (4) the

existence of de jure school segregation in Connecticut

from 1830 through 1868; (5) the origins and historical

interpretation of the equal protection and education

clauses of the 1965 Constitution; (6) a historical

overview of the options for school desegregation

presented to the state but not acted upon, 1954 to

1980. In his testimony, the materials upon which

Professor Collier may rely will include numerous

historical sources, including primarily but not limited

to Helen Martin Walker, Development of State Support

and Control of Education in Connecticut (State Board of

Education, Connecticut Bulletin #4, Series 1925-16);

Keith W. Atkinson, The Legal Pattern of Public

Education in Connecticut (Unpublished Doctoral

Dissertation, University of Connecticut, 1950); Annual

Reports of the Superintendent of the Common Schools,

1838-1955; Jodziewicz, Dual localism in 17th Century

Connecticut, Relations Between the General Court and

the Towns, (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, William

& Mary, 1974); Bruce C. Daniels, The Connecticut Town:

Growth and Development, 1635-1790, Middletown

Connecticut, Wesleyan University; Trumbull, Public

Records of the Colony of Connecticut; Public Records of

the State of Connecticut; Proceedings of the

Constitutional Convention of 1965; as well as the

documents listed in response to defendants’

interrogatory 5, Plaintiffs’ Responses to Defendants’

First Set of Interrogatories (October 30, 1990), and

the sources referenced in plaintiff's supplemental