Fields v. City of Fairfield Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 31, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fields v. City of Fairfield Jurisdictional Statement, 1962. 2fa73ea8-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c030957-e97f-4b02-ad70-283bf55f56fc/fields-v-city-of-fairfield-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

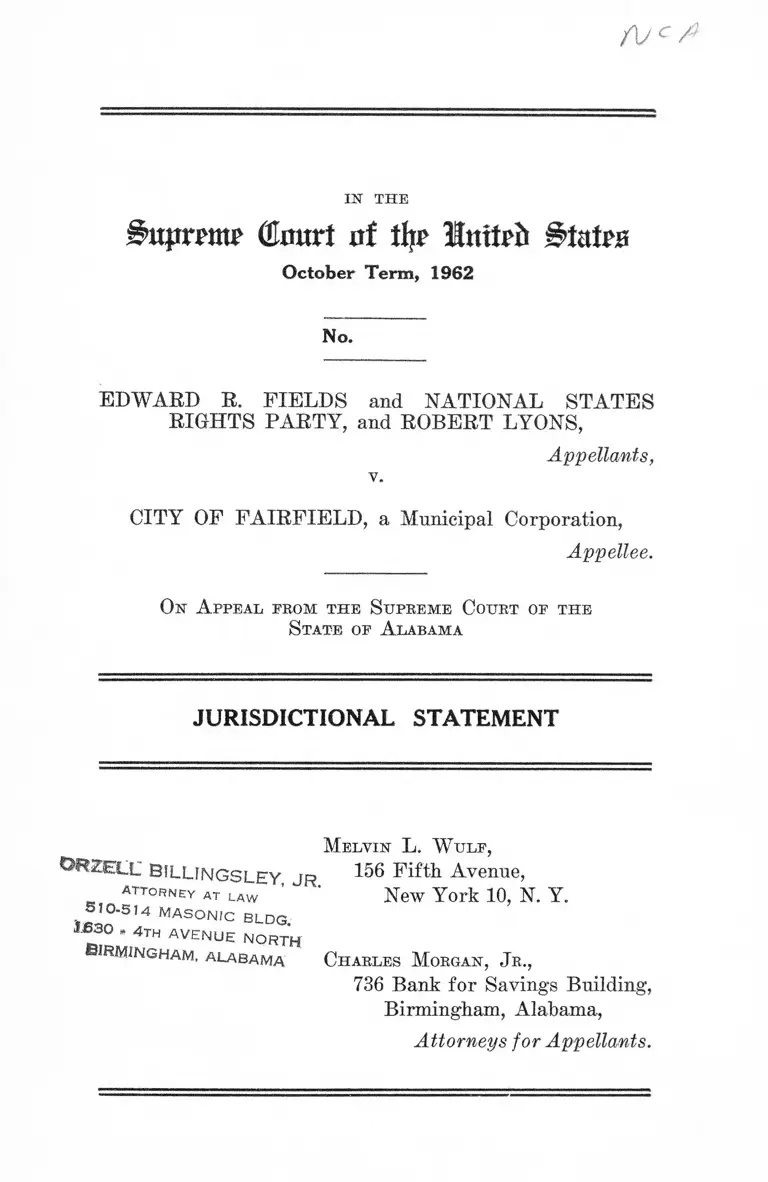

IN THE

^uprwitr GJmtrt of tk? Hmfrft States

October Term, 1962

No.

EDWARD R. FIELDS and NATIONAL STATES

RIGHTS PARTY, and ROBERT LYONS,

Appellants,

v.

CITY OF FAIRFIELD, a Municipal Corporation,

Appellee.

On A ppeal from the Supreme Court of the

State of A labama

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

ORZELL' Bill in g sl e y

atto r n ey at LAW

5 10 -5 1 4 MASONIC BLD<

1 6 3 0 . 4 th AVENUE NOR

Birmingham , a l a b a m ,

Melvin L. W ulf,

156 Fifth Avenue,

New York 10, N. Y.

Charles Morgan, Jr.,

736 Bank for Savings Building,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Attorneys for Appellants.

I N D E X

Opinions B e lo w ............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ..................................................................... 1

The Statutes Involved................................................... 2

Questions Presented..................................... 3

Statement of the C a se ................................................... 4

The Questions Are Substantial ................................. 7

Conclusion ...................................................................... 16

Table of Authorities

Cases :

Ayres, Re, 123 U. S. 433 ............................................ 13

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 5 1 6 ......................... 11

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252 ........................ 8,11

Building Service Employees v. Gazzam, 339 U. S.

532 ........................... 13

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 ............................. 8

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 IT. S. 296 .................. 11

Carpenters and Joiners Union v. Ritter’s Cafe,

315 U. S. 722 ........................................................... 13

Cox v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 569 .................... 9

Craig v. Harney, 331 U. S. 367 .............................. 8

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ........................... 9,11

Fisk, Ex Parte, 113 U. S. 713 .............................. 13

Garner v. State of Louisiana, 368 U. S. 1 5 7 .......... 15

Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Co., 336 U. S. 490 13

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652 ........................... 11

Green, In the Matter of, 369 U. S. 689 .................. 14

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233 . . . . 8

Hague v. CIO, 307 U. S. 496 ..................................... 7, 8

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U. S. 460 .............. 13

PAGE

11

Jamison v. Texas, 318 U. S. 4 1 3 ..................... 2, 7

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 ........................... 8, 9

Local 309 v. Gates, 75 F. Supp. 620 ..................... 9

Local Union No. 10i v. Graham, 345 U. S. 1 9 2 ........ 13

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. 8. 444 ................................. 2, 7, 8

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ..................... 11,12

NAACP, Ex Parte, 265 Ala. 349, 91 So. 2d 214 .. 12

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. 8. 697 . .................. .. 8

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 .................... 8

Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U. S. 3 3 1 .................... 8

Rowland, Ex Parte, 104 U. S. 604 ................. .. 13

Rockwell v. Morris, 10 N. Y. 2d 721, cert, denied,

368 U. S. 913 ........................................................ 11

Sawyer, Re, 124 U. S. 200 ................................. . 14

Schenk v. United States, 249 U. S. 4 7 ................... 11

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 ......................... 7

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 ............................... 2,14

Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60 ......................... 7

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ........................ 11

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 5 1 6 ................... 2,9,10,11

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ........ 15

United Gas, Coke & Chemical Workers v. Wis

consin Employment Relations Board, 340 U. S.

383 ............................................................................ 14

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U. S.

258 ................................................................... 12,13,14,15

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 ....................... 15

Yates v. United States, 354 U. S. 298 .................. 11

PAGE

PAGE

Constitution- and Statutes:

United States Constitution:

First Amendment............................... 3, 4, 7, 8,10,12,14

Fourteenth Amendment ............................... 3 ,4 ,7 ,9 ,15

General City Code of Fairfield:

Sections 3-4 .......................................................... 2, 3, 7, 8

Sections 3-5 ...........................................................2, 3, 7, 8

Sections 14-53 ......................................................... 1> 3, 8

Norris LaGuardia Act, 47 Stat. 7 0 .................... ... 12,13

28 U. S. C. §1257(2) ................................... ............ 2

Other A uthorities:

New York Times, October 30, 1962 .......................... 15

iii

1ST THE

j&uprrmr (Enurt at % Ittttefc States

October Term, 1962

No.

Edwakd E. F ields and National States E ights Party,

and E gbert Lyons,

Appellants,

v.

City op F airfield, a Municipal Corporation,

Appellee.

On A ppeal prom the Supreme Court of the

State of A labama

—-------— --------- O'— ------- -— •— •—

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama is re

ported at — Ala.—, 143 So. 2d 177 and set out infra at pp.

2a-7a. No opinion was written by the Circuit Court of

Jefferson County, but its oral opinion rendered at the

time of judgment is contained at E. 71-73 and is set out

infra at pp. 8a-9a.

Jurisdiction

(i) Appellee filed a bill of complaint (E. 2-3) in the

Circuit Court of Jefferson County on October 11, 1961,

alleging that appellants intended to hold a public meeting

without obtaining a permit, in violation of Section 14-53

2

of the General City Code of Fairfield, and had distributed

handbills announcing the meeting in violation of Sections

3-4 and 3-5 of the General City Code. The bill prayed that

“ a temporary writ of injunction or restraining order be

immediately issued by this Court * * * restraining [ap

pellants] from holding said meeting * * * and distributing-

said handbills,” and that the injunction be made permanent

after final hearing. The temporary writ (R. 5-6) was issued

the same day on appellee’s ex parte application. The next

day, appellants Fields and Lyons were found in criminal

contempt of the injunction and sentenced to five days in

jail and a $50 fine.

(ii) The judgment of conviction was affirmed and en

tered by the Alabama Supreme Court on June 14, 1962

(R. 101) and a timely application for rehearing was denied

on July 12, 1962 (R. 104). Execution of sentence was

stayed pending this appeal (R. 108). Notice of Appeal

to the Supreme Court of the United States was filed with

the Supreme Court of Alabama on September 10, 1962

(R. 109-111). An amended Notice of Appeal was filed on

September 18, 1962 (R. 112-113).

(iii) The jurisdiction of this Court to review by appeal

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama is con

ferred by 28 U. S. C. % 1257(2).

(iv) The cases which sustain the jurisdiction of this

Court are Lovell v. Griffin, 303 IT. S. 444; Jamison v. Texas,

318 U. S. 413; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516; Staub v.

Baxley, 355 U. S. 313.

The Statutes Involved

General City Code of F airfield, A labama

See. 3-4. Handbills, etc.—Distribution on streets.

It shall be unlawful for any person to distribute or

cause to be distributed on any of the streets, avenues, alleys,

parks or any vacant property within the city any paper

3

handbills, circulars, dodgers or other advertising matter,

[Ord. No. 354, §4 (1957).]

Sec. 3-5. Same—Placing or throwing in automobiles.

It shall be unlawful for any person to distribute in the

city any handbill or other similar form of advertising by

throwing or placing the same in any automobile or other

vehicle within the city. [Ord. No. 354, §5 (1957).]

Sec. 14-53. Public meetings; permit required.

It shall be unlawful for any person or persons to hold

a public meeting in the city or its police jurisdiction without

first having obtained a permit from the mayor, to do so.

[Ord. No. 184, § 4, 11-9-32.]

Questions Presented

1. Whether Sections 3-4 and 3-5 of the Oeneral City

Code of Fairfield, Alabama, upon which appellants’ con

tempt convictions rest, on their face or as construed and

applied in this case, abridge appellants’ rights of free

speech, press and assembly in violation of the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the First Amend

ment to the United States Constitution.

2. Whether Section 14-53 of the General City Code of

Fairfield, Alabama, upon which appellants’ contempt con

victions rest, on its face or as construed and applied in

this case, abridges appellants’ rights of free speech, press

and assembly in violation of the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment and the First Amendment to the

United States Constitution.

3. Whether consideration by the Supreme Court of the

United States of a challenge on federal grounds to the

validity of a municipal ordinance on its face, or as construed

and applied, may be precluded where appellants are found

in contempt of an ex parte temporary injunction which

4

purports to enforce compliance with the ordinance, and the

state court refuses to entertain the merits of the challenge

on the procedural ground that appellants “ chose to disre

gard the temporary injunction rather than contesting it by

orderly and proper procedure,” where the consequence of

the state procedural rule is to nullify appellants’ rights of

free speech, press and assembly in violation of the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the First

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

4. Whether appellants’ convictions for contempt, being

unsupported by any evidence of guilt, constitute wholly

arbitrary official action and thereby violate the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

Statement of the Case

I. When and How the Federal Questions Were Raised.

The federal questions presented by this appeal were

first raised by appellants in the Circuit Court on their oral

motion to dismiss (R. 66-69). They were raised thereafter

in appellants’ petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court

of Alabama (R. 84-86), and on the application for rehear

ing (R. 103).

II. The Facts.

Appellant Fields is Information Director of the National

States Rights Party. Appellant Lyons is Youth Organizer

of the Party (R. 57). The Party, which stands for white

supremacy and segregation (R. 53), has been on the ballot

in Alabama (R. 58).

Sometime prior to Wednesday, October 11, 1961 (R. 44),

the Party had handbills distributed in Fairfield which con

tained the following announcement (R. 42):

W hite W orkers

Meeting

*Niggers A re Taking Over U nions !

*Niggers W ant Our Parks and Pools !

#Niggers Demand M ixed Schools!

Communists in NAACP and in Washington say

Whites Have No Rights!

The Nigger gets everything he Demands !

White Supremacy Can be saved

Whites Can Stop this second Reconstruction!

Hear Important Speakers Prom 4 States

Time—8 P. M. Date—'Wed. Oct. 11

Place—5329 Valley Road

In Downtown Fairfield, Alabama

A bove the Car W ash

Thunderbolt Mobile Unit Will be Parked Out

Front Sponsored by National States Rights Party

Box 783, Birmingham, Alabama

P ublic I nvited

Come and Bring Your Friends

At about 5:00 P. M., Tuesday, October 10, 1961, the

day before the scheduled meeting, the Mayor of Fairfield

sent a notice to appellant Fields that he had violated a

city ordinance that prohibited the distribution of handbills.

The Mayor also informed Fields that another ordinance

forbade public meetings without a permit (R. 43).

At about 6 :00 P. M. the same evening, Fields phoned the

Mayor at his home to discuss the issuance of a permit for

the meeting (R. 36-38). Fields called the Mayor’s office

the morning of the following day and made an appointment

for 2 :Q0 P. M. that afternoon for further discussion (R. 55).

Around noon of that day, however, Fields was served with

an injunction (R. 24) forbidding him, the National States

6

Rights Party, their servants, agents and employees, from

holding the scheduled meeting and from distributing any

handbills announcing the meeting. Fields did not keep his

2:00 P. M. appointment.

The injunction was issued on the ex parte application

of the City of Fairfield. The Bill of Complaint (R. 2-4)

alleged, among other things, that the appellants were “ dis

tributing handbills of an inflammatory nature designed to

create ill will and disturbances between the races in the

City of Fairfield,” that the purpose of the announced meet

ing “ is to create ill will, disturbances, and disorderly con

duct between the races,” and that the meeting “ will con

stitute a public nuisance, injurious to the health, comfort,

or welfare of the City of Fairfield and * * * is calculated

to create a disturbance, incite to riot, disturb the peace,

and disrupt peace and good order in the City of Fairfield.”

About 7 :30 P. M. on the evening of the scheduled meet

ing, appellants Fields and Lyons arrived at the meeting

place to announce that the meeting site had been transferred

to the city park at Lipscomb, a nearby town (R. 16, 22, 25,

27, 49, 54, 60, 62, 63).1 Subsequent to the service of the

injunction, no meeting was held in Fairfield (R. 48, 55),

no handbills were distributed (R. 18, 22, 26, 31, 44, 47, 54,

63, 72),2 nor was there any disturbance whatsoever (R.

17, 25, 28, 55).

Appellants were arrested for violating the injunction.

On the following day, October 12, 1961, after a hearing,

each was found in contempt and sentenced to serve 5 days

in jail and pay a $50 fine.

1 Earlier the same day, appellant Lyons and another person were

prohibited by the police from entering the meeting place (R . 33, 50).

2 Some copies of the Party’s newspaper, Thunderbolt, were dis

tributed near the original meeting place, but it contained no notice of

the Fairfield meeting, nor had its distribution been enjoined. A copy

of the newspaper is contained at R. 19.

III. The Disposition Below of the Federal Questions.

The Circuit Court, although it found that “ the ordi

nances are a legal exercise of the police power of the

municipality” (R. 72), also found that “ I don’t believe it

is the law of this State that you can collaterally attack the

constitutionality of an ordinance in a contempt proceed

ing * * * ” (R. 71).

The Supreme Court of Alabama also found, the ordi

nances not unconstitutional (R. 100), but held that appel

lants “ may not raise the question of its unconstitutionality

in collateral proceedings on appeal from a judgment of con

viction for contempt of the order or decree * * * ” (R.

100).

The Questions Are Substantial

1. Sections 3-4 and 3-5 of the Code of Fairfield purport

to prohibit the distribution of “ any paper handbills, circu

lars, dodgers or other advertising matter,” at all times and

in all public places. A statute of that magnitude is uncon

stitutional on its face, for it abridges the rights of free

speech and free press that are secured by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444; Hague v. CIO, 307 U. S. 496;

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147; Jamison v. Texas, 318

U. S. 413; Talley v. California, 362 U. S'. 60.

Sections 3-4 and 3-5 are almost identical to the ordi

nances involved in Numbers 13, 18 and 29 in Schneider,

which, as the Court said, “ absolutely prohibit [distribution]

in the streets and, one of them, in other public places as

well.” 308 U. S. at 162. The Court held those ordinances

invalid on their face on the ground that they abridged

“ the free communication of information and opinion se

cured by the Constitution.” Id. at 163.

This case is aggravated by the fact that appellants were

restrained in advance from distributing any handbills what-

8

ever. Thus, appellee, relying upon Sections 3-4 and 3-5,

burdened appellants with a prior restraint, a particularly

noisome violation of the First Amendment, Near v. Minne

sota, 283 U. S. 697; Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495.

Moreover, the trial court explicitly found that no hand

bills were distributed after the injunction was served (ft.

72). What the court in fact found, was that appellants had

distributed copies of their newspaper, The Thunderbolt,

whose circulation had not been enjoined. Though the court

acknowledged that there was no announcement of the meet

ing in the issue distributed,8 it said, “ That was an artifice

on the part of someone to bring home the fact that the

meeting was going to be held while artfully evading the

exact language of the handbill that had been previously

distributed” ( R. 72). Thus, the high order of protection

conferred by the Constitution on the freedom of the press,

was arrantly disregarded. Near v. Minnesota, supra;

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. 8. 233; Bridges v.

California, 314 U. S. 252; Pennekamp v. Florid,a, 328 U. S.

331; Craig v. Harney, 331 U. 8. 367.

2. Section 14-53 of the Code of Fairfield requires that

a permit be obtained from the Mayor “ to hold a public

meeting in the city or its police jurisdiction.” Because the

ordinance contains no “ narrowly drawn, reasonable and

definite standards for the officials to follow # * it is

invalid on its face. Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268,

271; Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496, 516; Runs v. New

York, 340 TJ. S. 290. Mr. Justice Frankfurter, concurring 3

3 The issue consists of eight pages. The front page headline says

“ ‘Freedom Riders’ Burn Bus While Bobby Kennedy Blames 9

Innocent White Alabamians.” The centerfold headline said “ Ken-

nedys Start Second Reconstruction of South.” Two and a half pages

are devoted to excerpts from Henry Ford’s The International Jew

(R. 19).

9

in Runs, said, “ I f a municipality conditions holding street

meetings on the granting of a permit * * *, the basis which

guides licensing officials in granting or denying a permit

must not give them a free hand, or a hand effectively free

when the actualities of police administration are taken into

account.” 340 U. S. at 284-285.

The size of the free hand wielded against appellants,

when measured by its reach in this case, is remarkable.

The power it assumed was not restricted to regulating the

“ time, place and manner,” of a meeting on the streets or

in the parks,4 5 but rather it asserted the power to suppress

in advance a meeting of a political party to be held in a

private hall.

There have been two cases before this Court which

were concerned with the power asserted by a State to

prohibit a peaceful public meeting held in a private hall

merely because the purpose of the meeting was disagree

able to the government : DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353;

and Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516.®

In DeJonge, an Oregon statute purported to make crim

inal, among other things, “ the organization of an * * *

assemblage which advocates [criminal syndicalism], and

presiding at or assisting in conducting a meeting of such

an organization, society or group.” DeJonge’s “ sole of

fense as charged # # was that he had assisted in the

conduct of a public meeting, albeit otherwise lawful, which

was held under the auspices of the Communist Party.”

299 U. S. at 362.

The Court, holding the conviction repugnant to the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, said:

“ The holding of meetings for peaceable political

action cannot be proscribed. Those who assist in

4 Compare Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569, 576.

5 Compare Local 309 v. Gates, 75 F. Supp. 620.

1 0

the conduct of such meetings cannot be branded as

criminals on that score. The question, if the rights

of free speech and peaceable assembly are to he

preserved, is not as to the auspices under which the

meeting is to be held hut as to its purpose; not as

to the relations of the speakers, hut whether their

utterances transcend the hounds of the freedom of

speech which the Constitution protects. If the per

sons assembling have committed crimes elsewhere,

if they have formed or are engaged in a conspiracy

against the public peace and order they may be

prosecuted for their conspiracy or other violation

of valid laws. But it is a different matter when the

State, instead of prosecuting them for such offenses,

seizes upon mere participation in a peaceable as

sembly and a lawful public discussion as the basis

for a criminal charge.” 299 U. S. at 365.

In Thomas, an official of a labor union was held in

contempt of a restraining order-issued ex parte, as here—

that forbade him from violating a Texas statute regulating

the solicitation of membership in trade unions. The order

was issued in anticipation of a meeting at which the appel

lant was scheduled to speak. He appeared and spoke at

the meeting, and was held in contempt. The Court, hold

ing that the statute contravened the First Amendment,

said that “ a requirement that one must register before he

undertakes to make a public spech to enlist support for a

lawful movement is quite incompatible with the require

ments of the First Amendment,” 323 U. S. at 540.

Whether or not a State has the power to prohibit

in advance peaceful assemblies merely because its officials

prefer to suppress discussion of issues of public importance

or maintain the status quo, is a constitutional question of

the first magnitude. It is presented here in graphic form.

The purpose of the meeting organized by appellants was

to discuss race relations. Appellants maintain that the

white race is superior to the Negro race and are entirely

opposed to any form of racial integration. They intended

11

to discuss—and oppose—the integration of labor unions,

parks, pools and schools. Their opposition to integration,

of course, is constitutionally irrelevant. Compare Termi-

niello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, and Rockwell v. Morris, 10

N. Y. 2d 721, cert, denied, 368 U. S. 913, with N.A.A.C.P. v.

Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 and Bates v. Little R od , 361 U. S.

516.

The power of a State to suppress speech and assembly

may not be applied in advance, but only, if at all, when

there is a clear and present danger that the speech or as

sembly threatens to incite illegal conduct. Schenk v. United

States, 249 U. S. 47, Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652 (dis

sent), DeJonge v. Oregon, supra, Bridges v. California, 314

U. S. 252, Thomas v. Collins, supra. Compare Yates v.

United States, 354 U. S. 298. The record here is barren

of evidence of any such danger. Appellee’s bill of com

plaint contains no factual allegations to support its con

clusions that the purpose of the meeting was “ to create

ill will, disturbances, and disorderly conduct between the

race,” and that it “ will constitute a public nuisance, in

jurious to the health, comfort or welfare of the City of

Fairfield and * * * is calculated to create a disturbance,

incite to riot, disturb the peace, and disrupt peace and good

order in the City of Fairfield” (R. 3).6

The true purpose of the restraints imposed on appel

lants was revealed by the sentencing court. It said, ‘ ‘ Back

several years ago wTe did have a movement to move into

one of our public parks here but that was straightened out

within a matter of a few weeks * * *. And it is the intention,

I know, of the public officials * * # that we are going to do

everything we can to maintain that status quo” (R. 72).

But a State “ may not suppress free communication of

views * * # under the guise of preserving desirable con

ditions.” Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 308.

6 The record shows that a meeting held by appellants the previous

evening was entirely peaceable (R . 47).

12

The ruling below, if permitted to stand, will empower

the States to burden free speech, press and assembly to an

extent not heretofore tolerated by this Court. The decision

whether those burdens offend the First Amendment, re

quires full briefing and oral argument before the Court.

3. Whether or not a state rule of procedure may be

interposed between an individual and his rights of free

speech, press and assembly under the circumstances present

in this case, is a substantial federal question that has not

been decided by this Court.

The Alabama Supreme Court held that appellants could

test neither the constitutionality of the ordinances on which

the temporary injunction was based, nor the validity of

the injunction itself, by violating its terms. It relied

principally 7 on United States v. United Mine Workers, 330

U. S. 258, which involved the question whether the Norris-

LaGuardia Act prohibited a United States District Court

from enjoining a coal miners’ strike when the United

States was in possession of the mines. Although United

Mine Workers affirmed convictions of contempt of an ex

parte restraining order, the case is not authority for the

proposition that a contempt conviction is valid even if the

underlying order is void on constitutional grounds.

First, of the five Justices in the majority, three held the

order valid. Though they went on to declare that even

if the order were void, the defendants nonetheless were

required to obey it, that much of their opinion was unneces

sary to their decision and therefore not binding. Mr.

Justice Black and Mr. Justice Douglas likewise found the

order valid and thought it unnecessary, therefore, to decide

the academic problem of a void order. They dissented in

part on other grounds. Mr. Justice Murphy and Mr. Justice

Rutledge concluded both that the order was void and the

7 The opinion also cites E x Parte National Association for Ad

vancement of Colored People, 265 Ala. 349, 91 So. 2d 214, but

neglects to note that that case was reversed, in N.A.A.C.P. v. Ala

bama, 357 U. S. 449.

13

contempt conviction therefore invalid. Only Mr. Justice

Frankfurter and Mr. Justice Jackson held the contempt

conviction valid even though the order on which it was

based was, in their opinion, invalid. Thus, of nine Justices

writing five opinions, only Justices Frankfurter and Jack-

son squarely adopted the proposition advanced here by the

Supreme Court of Alabama.

Second, the issue in United Mine Workers dealt only

with the question whether the Norris-LaGuardia Act was

to be interpreted to prohibit a United States District Court

from enjoining a strike under the unique facts of that case.

There was no discussion in the Court’s opinion bearing

on the A ct’s constitutionality, nor was there any claim that

the Act was unconstitutional.

Third, there was substantial doubt whether the Norris-

LaGuardia Act applied to the facts in United Mine Workers,

for as the Court noted, the question “ had not previously

received judicial consideration.” 330 U. S. at 293. In

the case at bar, to the contrary, it is perfectly clear that

the ordinances in question are unconstitutional both on

their face and as construed and applied. See Points 1

and 2, supra. Consequently, the “ different result” which

Mr. Chief Justice Vinson anticipated, “ were the question

of jurisdiction frivolous and not substantial” , 330 U. S.

at 293, is required in this case.

Fourth, the nature of the United Mine Workers case,

dealing as it does with a labor dispute, sets it apart from

the instant case which comes here unfettered by the quali

fications that may attach to cases that concern industrial

conflict. Compare, Carpenters and Joiners Union v. Rit

ter ’s Cafe, 315 U. S. 722; Giboney v. Empire Storage d Ice

Co., 336 U. S. 490; Building Service Employees v. Gazsam,

339 U. S. 532; Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U. 8. 460;

Local Union No. 10 v. Graham, 345 U. S. 192.

Fifth, cases decided by this Court both before and after

United Mine Workers have held that a contempt conviction

under a void order is itself void. Ex Parte Rowland, 104

14

U. S. 604; Ex Parte Fish, 113 U. S. 713; Re Ayers, 123 U. S.

443; Re Satvyer, 124 U. S. 200. See also United Gas, Coke

& Chemical Workers v. Wisconsin Employment Relations

Board, 340 U. S. 383; In the Matter of Green, 369 U. S. 689.

By utilizing the supposed doctrine of United Mine

Workers, Alabama has effectively curtailed appellants’

rights of speech, press and assembly, and Mr. Justice Rut

ledge’s prophecy in his dissent in United Mine Workers

has come to pass:

“ [I ] f [the Court’s holding] should become the

law, for every case raising a question not frivolous

concerning the court’s jurisdiction to enter an order

or judgment, that punishment for contempt may be

imposed irrevocably simply upon a showing of vio

lation, the consequences would be equally or more

serious * *.

The First Amendment liberties especially would

be vulnerable to nullification by such control. Thus,

the constitutional rights of free speech and free

assembly could be brought to nought and censorship

established widely over these areas merely by apply

ing such a rule to every case presenting a substantial

question concerning the exercise of those rights.

* * * These and other constitutional rights would be

nullified by the force of invalid orders issued in flat

violation of the constitutional provisions securing

them, and void for that reason.” 330 TJ. S. at 351-

352.

If appellants were not judged in contempt of the pre

liminary injunction, but rather were convicted directly of

violating the ordinances on which the injunction was based,

there is no question that the ordinances’ constitutionality

could have been tested by violating them. Staub v. Baxley,

355 U. 8. 313. But Alabama, by interposing a temporary

injunction between appellants and the ordinances, has de

vised a method that, if ratified by this Court, will allow

circumvention of the Staub doctrine and confer on the states

a technique to nullify the precise purpose the First Amend

ment is intended to serve—full discussion of all matters of

15

public concern, which Mr. Justice Brandeis called “ a politi

cal duty.” Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357, 376 (con

curring opinion). Public issues frequently are short run,

and if the government were empowered to suppress dis

cussion by use of an injunction issued, as here on the

flimsiest ground,8 the purpose of the discussion may well

have passed by the time the appellate remedies were ex

hausted. For example, it would enable a political candidate

to be enjoined from speaking during the campaign period

preceding an election. I f he violated the injunction he

would be imprisoned; if he bowed to the injunction and

tested its constitutionality in “ orderly and proper pro

ceedings,” the election will have long ended. In either

case, the electorate would not have heard him and the

electoral process would be crippled.9

8 So flimsy “ as to be usurping judicial forms” , thereby satisfying

Mr. Justice Frankfurter’s criterion for treating the injunction “ as

though it were a letter to a newspaper.” United Mine Workers,

supra at 309-310.

9 On the day this Jurisdictional Statement was printed, the New

York Times carried the following story (October 30, 1962, p. 22) :

Los A n geles, Oct. 29— California Democrats won a court

order today against the sale and distribution of the controversial

Little Red Book until after the election.

Democrats alleged that the booklet, “ California: Dynasty of

Communism,” implied that Gov. Edmund G. Brown and other

Democratic incumbents were soft on Communism.

Superior Judge Kenneth N. Chantry issued a temporary re

straining order prohibiting the printing, posting or distribution

of the 32-page booklet. He set Nov. 7, the day after Election

Day, for a hearing on an injunction.

The order followed a libel suit for $500,000 damages brought

by Eugene L. Wyman, the state chairman, and other Demo

cratic leaders.

They alleged the booklet was designed to “ injure, defame,

discredit and defeat” Democratic officials.

It was contended the booklet contained false statements and

doctored photographs.

* * *

Judge Chantry ordered defendants to take back any copies

in the hands of postal officials.

16

Whether or not the Alabama rule of procedure an

nounced by the court below shall be permitted to stand

between appellants and their rights under the Constitution,

is a substantial federal question that should be fully briefed

and argued before the Court.

4. This Court has held that convictions devoid of evi

dentiary support are unconstitutional under the due pro

cess clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thompson v.

City of Louisville, 362 (J. S. 199; Garner v. State of

Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157. This is such a case.

The Circuit Court expressly found that “ there is no

evidence that the pamphlet was re-distributed” (R. 72),

but as we pointed out above, he held that the injunction

was violated by the distribution of appellants’ newspaper

even though it contained no notice of the meeting. The

Circuit Judge said nothing at all about whether the evi

dence sustained a finding that appellants had violated the

ban on the scheduled meeting—nor could he, for it is un

disputed that appellants had cancelled it. Although appel

lants were in the vicinity of the meeting hall, it was only

to notify those persons who may have come to the an

nounced meeting place, that the meeting was to be held

elsewhere, outside the City of Fairfield. Nonetheless, the

Supreme Court of Alabama said that “ There is evidence

to support the finding that they did violate the terms of

the temporary injunction” (R. 100).

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, it is urged that jurisdiction

be noted.

Respectfully submitted,

Melvin L. W ulf,

156 Fifth Avenue,

New York 10, N. Y.

Charles Morgan, Jr.,

736 Bank for Savings Building,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Attorneys for Appellants.

October 31, 1962.

APPENDIX

The Supreme Court op A labama

Thursday, June 14, 1962

The Court Met Pursuant to Adjournment

Present: All the Justices

Jefferson Circuit Court

Bessemer Division

6th Div. 801: 802: 809

---------------------- o—----------------------

Dr. E dward E. F ields and National States Rights Party,

vs.

City of F airfield, a Municipal Corporation.

---------------------- o----------- ----- ——

The said causes having been consolidated, W hereupon,

Come the parties by attorneys and the record and mat

ters therein assigned for errors, being argued and sub

mitted on motions and merits and duly examined and

understood by the Court, it is considered that in the record

and proceedings of the Circuit Court' there is no error.

It is therefore considered, ordered and adjudged that

the judgment of the Circuit Court be in all things affirmed.

I t is further considered, ordered and adjudged that

the Appellants-Petitioners, Edward R. Fields and Robert

Elsworth Lyons, and Dr. Fred Short and Pearce S. John

son, sureties on the appeal bond, pay the costs of appeal

of this Court and of the Circuit Court.

And it appearing that said parties have wrnived their

rights of exemption under the laws of Alabama, it was

ordered that execution issue accordingly.

[Judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama]

2a

-------------------------------- o — — --------------- --------

Dr. E dward R. F ields and National States Rights Party,

[Opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama]

v.

City oe F airfield, a Municipal Corporation.

A ppeal from Jefferson Circuit Court

------------------------- o—------ — —■—-

Merril, Justice:

Dr. Edward R. Fields and Robert Lyons were adjudged

to be in contempt of circuit court because they had been

found guilty of violating a temporary injunction issued

by the court against them as individuals, and against the

National States Rights Party, of which they were officers,

enjoining them from conducting an advertised meeting in

Fairfield. Fields and Lyons were each fined $50 and

sentenced to five days in jail.

Petitioners "appealed” their judgment of conviction

to this court and later their attorney "discovered that

writ of certiorari is the proper remedy in this case,”

and asked that the purported appeal be considered as a

petition for writ of certiorari. We have complied with

the request and so treat the cause now under review.

Petitioners were distributing handbills in the City of

Fairfield, which read:

3a

“ W hite W orkers

‘ ‘ Meeting

‘ ‘ * Niggers A re Taking Over U nions!

“ #N iggers W ant Our Parks and Pools!

“ * Niggers Demand M ixed Schools!

“ Communists in NAACP and in Washington say

“ Whites H ave No Rights!

“ The Nigger gets everything he Demands!

“ White Supremacy Can be saved!

Whites Can Stop this second Reconstruction!

“ Hear Important Speakers from 4 States

‘ ‘ Time—8 P. M. Date—Wed. Oct. 11

“ Place—5329 Valley Road

“ In Downtown Fairfield, Alabama

“ A bove the Car W ash

“ T hunderbolt Mobile Unit Will Be Parked Out

Front Sponsored by National States Rights Party

“ Box 783, Birmingham, Alabama

“ P ublic I nvited

“ Come and Bring Your Friends!”

The attorney for the city sought a temporary injunc

tion to enjoin petitioners from holding the advertised

meeting because they had not complied with an ordinance

of the City Code which provided “ It shall be unlawful for

any person or persons to hold a public meeting in the

city or police jurisdiction without first having obtained

a permit from the mayor to do so.” The judge issued

Opinion of Supreme Court of Alabama

4a

the temporary injunction and a copy was served on Fields

at Noon, Wednesday, August 11th. Lyons also had notice

of the temporary injunction which enjoined them “ from

holding a public meeting at 8 P.M. on Wednesday, October

11, 1961, at 5329 Valley Road, Fairfield, Alabama, as

announced, and from distributing further in the City of

Fairfield, handbills announcing such meeting such as were

distributed in the City of Fairfield, Alabama, on October

10, 1961, until further orders from this Court; and this

you will in no wise omit under penalty, etc.”

Fields and Lyons were arrested that night where a

crowd had gathered across the street from the advertised

place of meeting. Fields was making announcements to

the crowd and both he and Lyons were distributing copies

of ‘ ‘ The Tunderbolt, ’ ’ the newspaper of the Party.

The petitioners make two points in brief. They say

first that the evidence shows they did not violate the terms

of the injunction. There is evidence to support the find

ing that they did violate the terms of the temporary in

junction, and we have held that upon petition for certiorari,

the court does not review questions of fact but only ques

tions of law; but if the court below misapplies the law

to the facts as found by it or there is no evidence to sup

port the finding, a question of law is presented to be

reviewed upon the petition for certiorari. Ex parte Wetsel,

243 Ala, 130, 8 So. 2d 824.

We now come to the main point argued by petitioners—

“ that the temporary injunction was void ab initio on ac

count of being contrary to and in violation of both the

United States and Alabama Constitutions.” This argu

ment is based upon the premise that the ordinance of the

City of Fairfield is unconstitutional. We cannot say that

it is unconstitutional on its face.

In Ex parte National A ss ’n for Adv. of Colored Peo

ple, 265 Ala. 349, 91 So. 2d 214, we said:

Opinion of Supreme Court of Alabama

5a

“ On the petition for certiorari the sole and only

reviewable order or decree is that which adjudges

the petitioner to be in contempt. Certiorari cannot

be made a substitute for an appeal or other method

of review. Certiorari lies to review an order or

judgment of contempt for the reason that there is

no other method of review in such a case. Ex parte

Dickens, 162 Ala. 272, 50 So. 218, 220. Review on

certiorari is limited to those questions of law which

go to the validity of the order or judgment of con

tempt,, among which are the jurisdiction of the court,

its authority to make the decree or order, violation

of which resulted in the judgment of contempt. It

is only where the court lacked jurisdiction of the pro

ceeding, or where on the face of it the order diso

beyed was void, or where procedural requirements

with respect to citation for contempt and the like

were not observed, or where the fact of contempt is

not sustained, that the order or judgment will be

quashed.”

Here, the circuit court had jurisdiction of the parties and

the subject matter. It had the authority to make the de

cree or order, and on its face, the order disobeyed was not

void. It is not contended that any procedural requirements

were omitted.

In the face of this, petitioners, without moving to dis

solve the temporary injunction, seeking a hearing, or in

any way contesting the writ, proceeded to meet a crowd

gathered across the street from the advertised place of

meeting and distributed inflammatory literature.

As a general rule, an unconstitutional statute is an ab

solute nullity and may not form the basis of any legal right

or legal proceedings, yet until its unconstitutionality has

been judicially declared in appropriate proceedings, no per

Opinion of Supreme Court of Alabama

6a

son charged with its observance under an order or decree

may disregard or violate the order or the decree with im

munity from a charge of contempt of court; and he may

not raise the question of its unconstitutionality in collat

eral proceedings on appeal from a judgment of conviction

for contempt of the order or decree, or an application for

habeas corpus for release from imprisonment for contempt.

United States v. United Mine Workers of America, 380

U. S. 258, 91 L. Ed. 884, 67 S. Ct. 677; Eowat v. Kansas,

258 U. S. 181, 66 L. Ed. 550, 42 S. Ct. 277; People v. Bou

chard, 6 Misc. 459, 27 N. Y. S. 201; McLeod v. Majors, 5th

Cir., 102 F. 2d 128; Pure Milk Asso. v. Wagner, 363 111. 316,

2 N. E. 2d 288.

In the United Mine Workers case, supra, the court said:

“ Proceeding further, we find impressive author

ity for the proposition that an order issued by a

court with jurisdiction over the subject matter and

person must be obeyed by the parties until it is re

versed by orderly and proper proceedings. This is

true without regard even for the constitutionality

of the Act under which the order is issued. In Howat

v. Kansas, 258 U. S. 181, 189-190 (1922) this Court

said:

‘ An injunction duly issuing out of a court of

general jurisdiction with equity powers upon

pleadings properly invoking its action, and served

upon persons made parties therein and within

the jurisdiction, must be obeyed by them how

ever erroneous the action of the court may be,

even if the error be in the assumption of the

validity of a seeming but void law going to the

merits of the case. It is for the court of first

instance to determine the question of the valid

ity of the law, and until its decision is reversed

Opinion of Supreme Court of Alabama

7a

for error by orderly review, either by itself or

by a higher court, its orders based on its decision

are to be respected, and disobedience of them is

contempt of its lawful authority, to be punished.’

“ Violations of an order are punishable as crim

inal contempt even though the order is set aside on

appeal, Worden v. Searle, 121 IT. S. 14 (1887), or

though the basic action has become moot, Gompers

v. Bucks Stove d Range Co., 221 U. S. 418 (1911).

“ We insist upon the same duty of obedience

where, as here, the subject matter of the suit, as well

as the parties, was properly before the court; where

the elements of federal jurisdiction were clearly

shown; and where the authority of the court of first

instance to issue an order ancillary to the main suit

depended upon a statute, the scope and applicability

of which were subject to substantial doubt. * * * ”

Under these authorities, petitioners were guilty of con

tempt, as they chose to disregard the temporary injunction

rather than contesting it by orderly and proper proceedings.

Affirmed.

Livingston, C. J., Simpson and Harwood, JJ., concur.

Opinion of Supreme Court of Alabama

8a

The Court: Well, gentlemen, before I give you my

decision, I have a remark or two I would like to make.

First, I don’t believe it is the law of this State that

you can collaterally attack the constitutionality of an ordi

nance in a contempt proceeding without first purging your

self of that contempt, if there is any there.

And, second, it has been, either through good luck or

the grace of somebody bigger than all of us here in the

Bessemer Cut-off, that we have been singularly blessed

with not having any race incident here in this area; and,

particularly, I think, Fairfield has never had one. Back

several years ago we did have a movement to move into

one of our public parks here but that was straightened

out within a matter of a few weeks by the City Attorney

for Bessemer and other people. And since that time I

don’t believe we have had a singie clash between the races,

either in Bessemer, or Fairfield, or any of the other city—

cities of the Bessemer Division of this County. And it

is the intention, I know, of the public officials, both of this

county and of the various municipalities of the Bessemer

Division of this County that we are going to do everything

we can to maintain that status quo. We are going to try

to keep peace between the races here and we are going

to do everything that we can to keep people from agitating

trouble.

Getting down to this case here:

While there is no evidence that the pamphlet was re

distributed, the writ of injunction says “ distribute further

handbills, announcing such meetings, as were distributed

in the City of Fairfield. ’ ’

I am impressed by the tone and the context of the

paper that was admittedly distributed and I simply think

that was an artifice on the part of someone to bring home

the fact that the meeting was going to be held while artfully

[O p in io n o f th e C ircu it C o u rt o f J efferso n C o u n ty ]

9a

evading the exact language of the handbill that had been

previously distributed.

If these respondents were of the opinion and so advised

that these ordinances were unconstitutional they could have

filed their motion to dissolve it and had their day in court

and the final hearing on this injunction was to have been

set down or was set down on November 17th, giving every

body adequate time to prepare their cases to come in and

test the constitutionality of these ordinances.

It is my opinion that the ordinances are a legal exercise

of the police power of the municipality.

Therefore, Dr. Fields and Mr. Lyons, if you will stand:

It is the judgment of the Court that you are in contempt

of this Court and it is the judgment of the Court that you

be and are hereby adjudged in contempt and you are

fined $50.00.

And as additional punishment you are ordered to be

confined in the county jail for five days.

Opinion of the Circuit Court of Jefferson County

DRZEU- B'lUNSSLEV, JR.

a tto rn ey AT

avenue north

rS B 30 a ATH AVt.1 ■

T he Hecla Press, 54 Lafayette Street, New Y ork City, BEekman 3-2320

«sgfjî 39

(2145)