Jack & Jill Assist Legal Defense Fund

Press Release

February 20, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 2. Jack & Jill Assist Legal Defense Fund, 1965. f43f1faf-b592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5c1245a2-b6d7-403a-8eb8-af5fd84dc77f/jack-jill-assist-legal-defense-fund. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

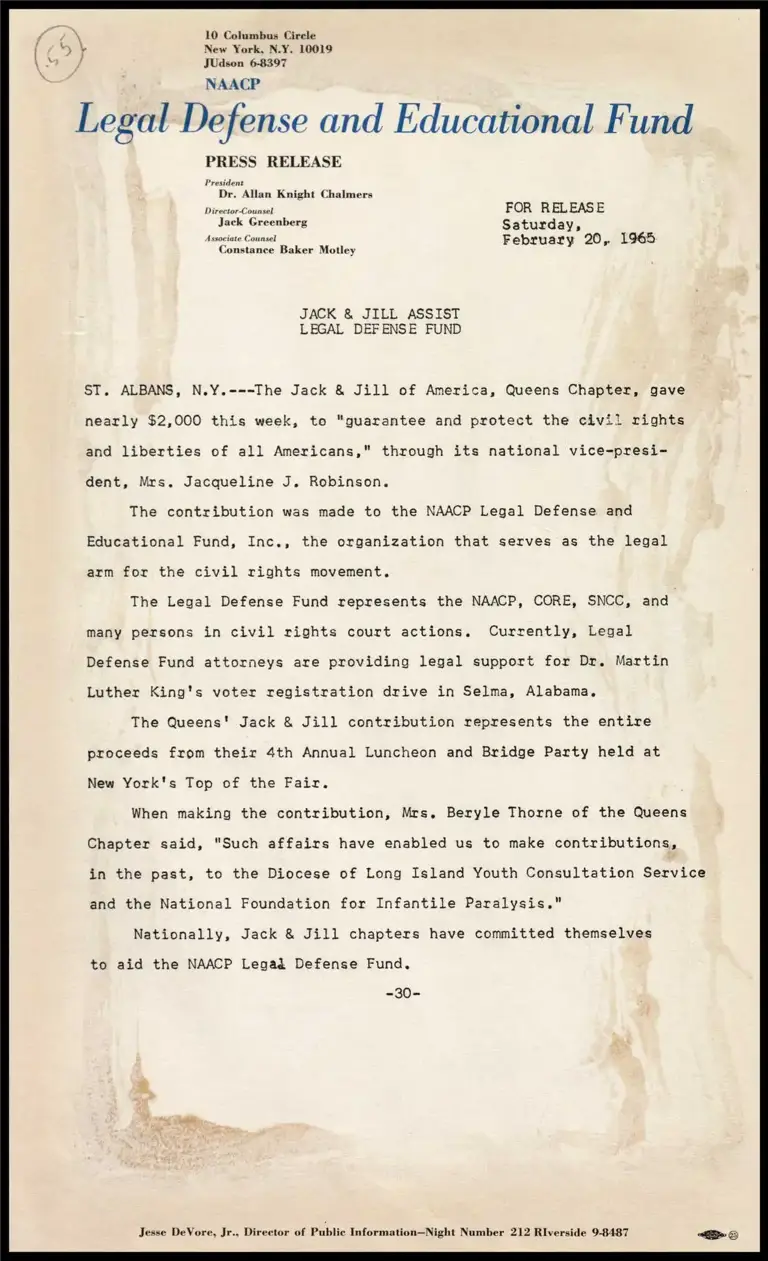

\ 10 Columbus Circle

\ New York, N.Y. 10019

JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

President

De Allan Knight Chalmers

Director-Counsel FOR RELEASE

Jack Greenberg Saturday,

Bonaseal February 20, 1965

stance Baker Motley

JACK & JILL ASSIST

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

ST. ALBANS, N.Y.---The Jack & Jill of America, Queens Chapter, gave

nearly $2,000 this week, to "guarantee and protect the civil rights

and liberties of all Americans," through its national vice-presi-

dent, Mrs. Jacqueline J. Robinson.

The contribution was made to the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., the organization that serves as the legal

arm for the civil rights movement.

The Legal Defense Fund represents the NAACP, CORE, SNCC, and

many persons in civil rights court actions. Currently, Legal

Defense Fund attorneys are providing legal support for Dr. Martin

Luther King's voter registration drive in Selma, Alabama.

The Queens' Jack & Jill contribution represents the entire

proceeds from their 4th Annual Luncheon and Bridge Party held at

New York's Top of the Fair.

When making the contribution, Mrs. Beryle Thorne of the Queens

Chapter said, "Such affairs have enabled us to make contributions,

in the past, to the Diocese of Long Island Youth Consultation Service

and the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis."

Nationally, Jack & Jill chapters have committed themselves

to aid the NAACP Legad Defense Fund.

—o0=

ue

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Inf i Night Number 212 RI ide 9-8487