Ltr. to David Lipman from L. Guinier

Correspondence

February 6, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Ltr. to David Lipman from L. Guinier, 1984. ea02d7d2-d492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5e5f881c-2145-4aca-b6ed-a6281cef7d54/ltr-to-david-lipman-from-l-guinier. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

Lesa,U&renseH"

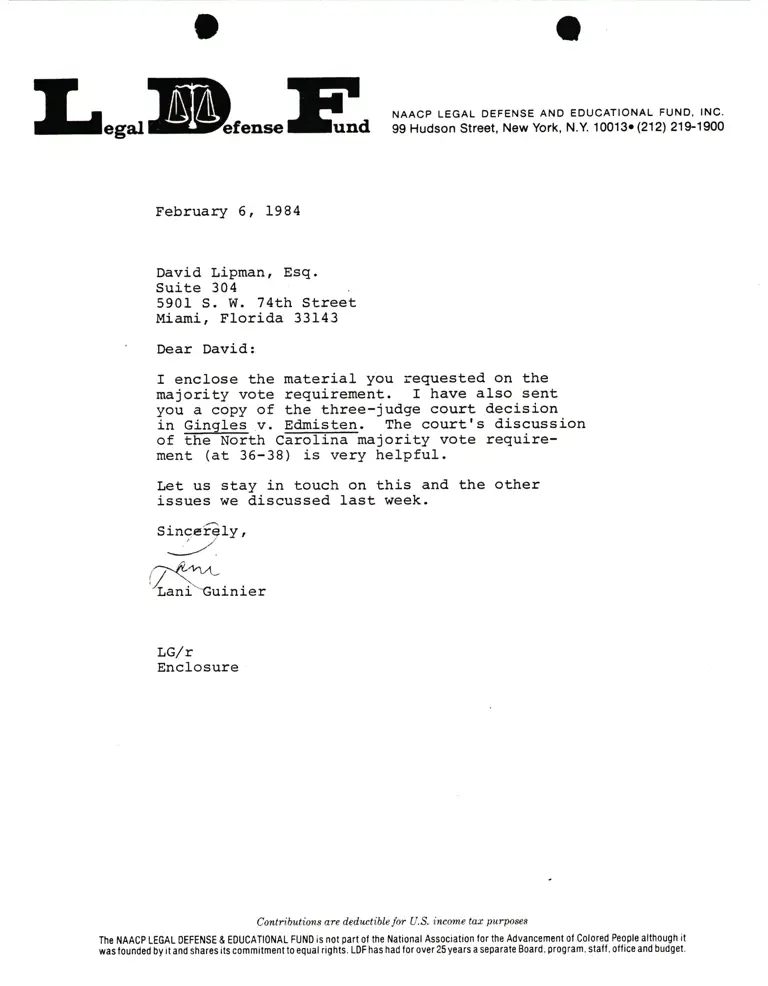

February 6, 1984

David Lipman, Esg.

suite 304

5901 S. W. 7At}. Street

Miami, Florida 33143

' Dear David:

I enclose the material you requested on the

majority vote requirement. I have also sent

you a copy of the three-judge court decision

ment (at 36-38) is very he1pful.

Let us stay in touch on this and the other

issues we discussed last week.

sinceGly,

.:/

'Lani\ui.nier

LG/r

Enclosure

Contributions are dedu,ctible lor U.S. incom.e tat purposes

The NAACP LEGAL 0EFENSE & EDUCATIoNAL FUND is not part ol the National Association lor the Advancemont ol Colored People although it

was founded by it and sharss its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 25 years a separate Board, program, stalf, otlice and budget.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE ANO EDUCATIONAL FUND' INC.

99 Hudson Street, New york, N.Y. 10013r (212) 219.1900

in Gingles v. EdmiFten. The court's dj-scussion

of EhE Nortn carofilna majority vote require-