Order

Public Court Documents

December 7, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Order, 1983. 016ddfb3-d492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5fb26841-c7f3-49c6-af9c-97b42094e0ac/order. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

R:JI:VEBJ

UEU 7 EE3

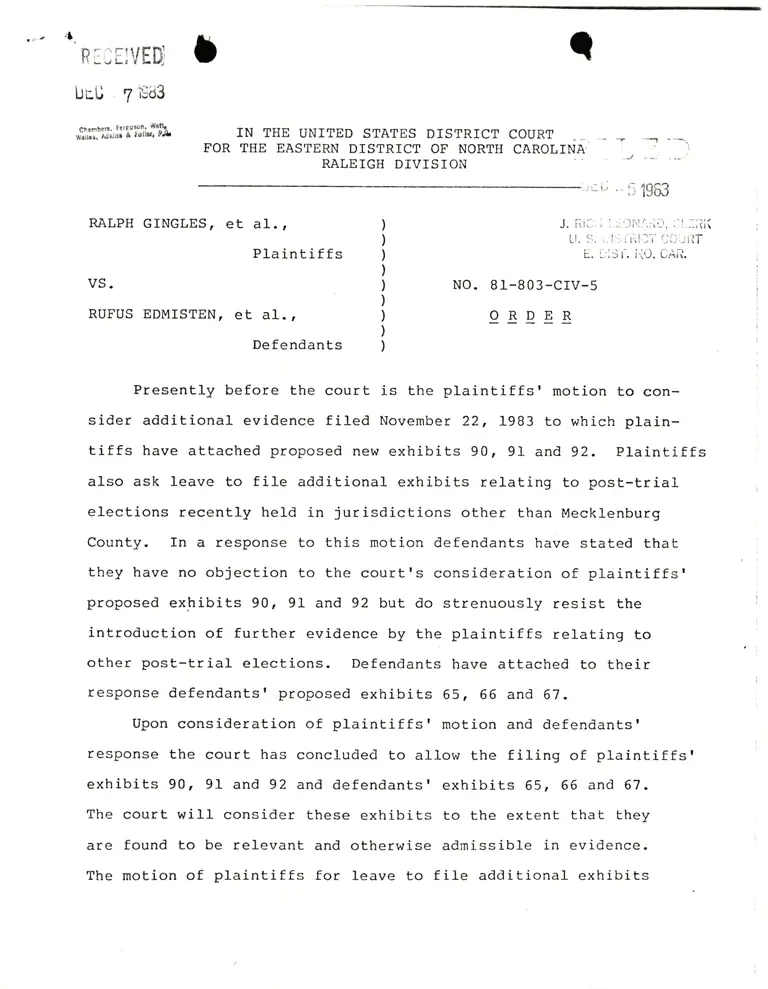

.:1,'"T:iti, ff ' il }"i i.l'rh IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALETGH DIVISION

RALPH GINGLES, €t aI.,

Plaintiffs

VS.

RUFUS EDMfSTEN, €t dI.,

Defendants

J. iirC. ; : r:'-)l\1.^,r'ii-i, :. l.--,ii(

Ll. Sl. '. i :.r'r:rllJ- ll).-: iiT

f. ::iSl-. i,:O. CAn.

NO.81-803-Crv-5

ORDER

Presently before the court is the plaintiffs' motion to con-

sider additional evidence filed November 22, 1983 to which plain-

tiffs have attached proposed new exhibits 90, 91 and 92. Plaintiffs

also ask leave to file additional exhibits relating to post-trial

elections recently held in jurisdictions other than Mecklenburg

County. In a response to this motion defendants have stated that

they have no objection to the courtrs consideration of plaintiffs'

proposed exhibits 90, 91 and 92 but do strenuously resist the

introduction of further evidence by the plaintiffs relating to

other post-trial elections. Defendants have attached to their

response defendantsr proposed exhibits 65, 66 and 67.

Upon consideration of plaintiffsr motion and defendants'

response the court has concluded to allow the filing of plaintiffsr

exhibits 90, 91 and 92 and defendants' exhibits 65, 66 and 67.

The court will consider these exhibits to the extent that they

are found to be relevant and otherwise admissible in evidence.

The motion of plaintiffs for leave to file additional exhibits

.t_

post-tria1 elections

County is denied.

held in jurisdictions other thanrelating to

Mecklenburg

December 5, 1983.

""

o:."t.

,:. -o.g.i'-.{\

-rr;:d.'w'

r. T. DUPREE,

UNITED STATES

Paoe 2